Bright Young Things discussion

This topic is about

Hans Fallada

Favourite Authors

>

Hans Fallada

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

By the way, this live webchat with Dennis Johnson, the publisher who brought Hans Fallada back to prominence with English readers is worth a read.

I think that Every Man Dies Alone, aka Alone in Berlin is one of the best books I have ever read. Hans Fallada was such an interesting person too.

I think that Every Man Dies Alone, aka Alone in Berlin is one of the best books I have ever read. Hans Fallada was such an interesting person too.I recently read a book of his short stories,Tales from the Underworld; Selected Shorter Fiction that have recently been released by Penguin and I have a review of it at http://leftontheshelfbookblog.blogspo....

I have a copy of Little Man, What Now? on my bookshelf that I haven't got around to reading yet.

^ Thanks Anna - that's all very interesting.

^ Thanks Anna - that's all very interesting.Anna wrote: "I think that Every Man Dies Alone, aka Alone in Berlin is one of the best books I have ever read"

I keep coming across people, like you, who cannot praise Every Man Dies Alone (aka Alone in Berlin) highly enough. I hope it gets the nod for our April BYT fiction choice - it's currently joint first place. My copy is due to arrive at my local library any day now.

It's great that so much of his work is being republished.

It might be worth mentioning that aside from the return to print this month of a selection of Fallada's works of short fiction, collected under the title 'Tales from the Underworld; Selected Shorter Fiction [Penguin Modern Classics], Penguin will be bringing another Hans Fallada novel back into print in July 2014. This time, it's 'Iron Gustav," originally published in 1940.

From the publisher:

"A powerful story of the shattering effects of the First World War on both a family and a country - from the author of bestselling Alone in Berlin.

Intransigent, deeply conservative coachman Gustav Hackendahl rules his family with an iron rod, but in so doing loses his grip on the children he loves. Meanwhile, the First World War is destroying his career, his country and his pride in the German people. As Germany and the Hackendahl family unravel, Gustav has to learn to compromise if he is to hold onto anything he holds dear.

Iron Gustav is both a moving, realist account of the aftermath of the First World War, and a deeply involving story of a family in crisis. Yet running through the unflinching truth, immediacy and emotional power of Fallada's prose is the charming, almost folkloric whimsicality that makes him such a master story-teller."

These are exciting times for fans of the BYT era.

I decided to start my own Fallada journey by finding out more about him and his life. I usually go about these things the other way round - read lots of a writer's work and then read a biography. I think I may try and adopt this approach in future.

Having almost finished More Lives Than One: A Biography of Hans Fallada by Jenny Williams, I feel I'll be equipped with plenty of background knowledge to enhance my understanding and enjoyment of Hans Fallada.

If this thread inspires you to want to read

If this thread inspires you to want to read Every Man Dies Alone , aka Alone in Berlin , then....

.....click here to participate in the vote for the BYT April 2014 fiction choice poll.

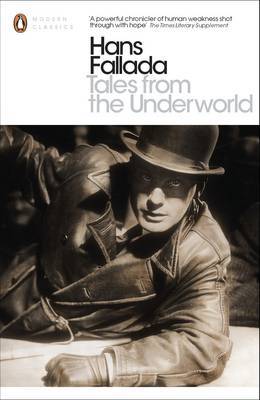

Tales from the Underworld by Hans Fallada

^ I love the cover to this new book.

Penguin Modern Classics have done a splendid job - as usual.

I've just spotted Anna's blog post about Tales from the Underworld.

Anna, I hope you don't mind me adding a link here....

Click here to read Anna's review of Tales from the Underworld

I'm glad you liked my review. I enjoyed the collection of stories very much.

I'm glad you liked my review. I enjoyed the collection of stories very much. I agree with you about the cover. It creates the right atmosphere for the stories even before getting started on them.

I have now finished...

I have now finished...

More Lives Than One: A Biography of Hans Fallada by Jenny Williams

A stunning, if somewhat depressing, biography of Hans Fallada.

Hans Fallada was all but forgotten outside Germany when his 1947 novel, Alone in Berlin (US title: Every Man Dies Alone), was reissued in English in 2009, whereupon it became a best seller and reintroduced Hans Fallada's work to a new generation of readers.

Jenny Williams, here refers to Hans Fallada as Rudolf Ditzen - his real name, and the name he used throughout his life. Where this biography scores especially highly for me is in its clear eyed depiction of Germany for the first 50 years of the twentieth century.

Rudolf Ditzen grows up in the rigid, authoritarian German society of the pre-World War One Wilhelmine era and this biography throws up all kinds of fascinating details about everyday life and social trends. Here's one example, when Rudolf was a teenager there were an extraordinary number of suicides in Rudolf's class. This was part of a much broader wave of suicides and suicide attempts that swept through Germany in the years before World War One. Germany's strict society during this period apparently inducing despair and hopelessness amongst many of the young.

Ditzen was a deeply troubled individual, prone to bouts of mental torment resulting in regular periods in psychiatric care. He was also variously addicted to drugs and alcohol, stole and spent time in jail, and was unfaithful to his first wife. All of these behaviours were exacerbated during the Nazi era and, again, Jenny Williams perfectly evokes the living hell of everyday life for many ordinary Germans under this regime.

Ditzen is denounced by neighbours on numerous occasions throughout the 1930s and 1940s and, on one occasion, this results in a spell in prison, the confiscation of the house he owned, and plunges him into another of his regular nervous breakdowns. Ditzen is generally viewed with suspicion by the Nazis and therefore has to severely compromise his work by retreating into children's stories and innocuous historical fiction having been declared an 'undesirable author'. Whilst many contemporaries emigrated he chose to stay in Germany and was therefore perfectly placed to witness, first-hand, the everyday horrors during this era.

I read this biography before reading any of Hans Fallada's work. I now feel very well informed about his life and work, and I am feeling very enthused about reading his books. Ditzen's friend and colleague, Paul Mayer, is quoted at the end of the book: "German literature has not many realistic writers. Hans Fallada is one of them. His work, mutilated by political terror, is even as a torso important enough not to be forgotten."

This book works on so many levels, and includes memorable insights into the social history of Germany, the life of a tortured artist, and the subtle but insistent day-to-day horrors of life under a fascist regime.

4/5

Books mentioned in this topic

Every Man Dies Alone (other topics)More Lives Than One: A Biography of Hans Fallada (other topics)

Alone in Berlin (other topics)

Tales from the Underworld: Selected Shorter Fiction (other topics)

Alone in Berlin (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Hans Fallada (other topics)Jenny Williams (other topics)

Hans Fallada (other topics)

Hans Fallada (other topics)

Jenny Williams (other topics)

More...

Hans Fallada (21 July 1893 – 5 February 1947) was a German writer of the first half of the 20th century. Some of his better known novels include Little Man, What Now? (1932) and Every Man Dies Alone (1947).

His works belong predominantly to the New Objectivity literary style, with precise details and journalistic veneration of the facts. Fallada's pseudonym derives from a combination of characters found in the Grimm's Fairy Tales: the protagonist of Hans in Luck (KHM 83) and a horse named Falada in The Goose Girl.

Here's Fallada's Wikipedia entry which makes interesting reading. Billy Childish cites him as a major influence.

I will definitely be exploring his work. My library service has a few copies of Alone in Berlin and I have a copy on order.

As a first tentative step into the world of Hans Fallada, I am currently reading...

This review gives a good flavour of More Lives Than One: A Biography of Hans Fallada by Jenny Williams. It is really interesting.

I should finish it later today.

Here's some more information...

First published in 1998, Williams's biography has been updated and reissued in the wake of the extraordinary recent success of a new translation of Alone in Berlin. She has colourful material to work with, as Rudolph Ditzen (who adopted the pen name Hans Fallada) killed a friend in a youthful suicide pact that went disastrously wrong, went to jail as a serial embezzler, and throughout his life had spells undergoing treatment for psychiatric problems and drug addiction. His response to the Nazi era was far less courageous than that of Alone in Berlin's protagonists, largely consisting of getting drunk and hiding in a rural backwater – though he was recognised as an anti-fascist by the Soviet occupiers in 1945, who bizarrely made him a mayor. Yet somehow Ditzen remained a productive, commercial author, known for low-life realism and giving a voice to the beleaguered "little man". A more novelistic biographer would have exploited the dramatic potential of the crises, but Williams's life is astute, rigorously researched and engrossing.