The Pickwick Club discussion

Shorter Works of Dickens

The Late Mr. Stanfield

The Late Mr. Stanfield"Every Artist, be he writer, painter, musician, or actor, must bear

his private sorrows as he best can, and must separate them from the

exercise of his public pursuit. But it sometimes happens, in

compensation, that his private loss of a dear friend represents a

loss on the part of the whole community. Then he may, without

obtrusion of his individuality, step forth to lay his little wreath

upon that dear friend's grave.

On Saturday, the eighteenth of this present month, Clarkson

Stanfield died. On the afternoon of that day, England lost the

great marine painter of whom she will be boastful ages hence; the

National Historian of her speciality, the Sea; the man famous in all

countries for his marvellous rendering of the waves that break upon

her shores, of her ships and seamen, of her coasts and skies, of her

storms and sunshine, of the many marvels of the deep. He who holds

the oceans in the hollow of His hand had given, associated with

them, wonderful gifts into his keeping; he had used them well

through threescore and fourteen years; and, on the afternoon of that

spring day, relinquished them for ever.

It is superfluous to record that the painter of "The Battle of

Trafalgar", of the "Victory being towed into Gibraltar with the body

of Nelson on Board", of "The Morning after the Wreck", of "The

Abandoned", of fifty more such works, died in his seventy-fourth

year, "Mr." Stanfield.--He was an Englishman.

Those grand pictures will proclaim his powers while paint and canvas

last. But the writer of these words had been his friend for thirty

years; and when, a short week or two before his death, he laid that

once so skilful hand upon the writer's breast and told him they

would meet again, "but not here", the thoughts of the latter turned,

for the time, so little to his noble genius, and so much to his

noble nature!

He was the soul of frankness, generosity, and simplicity. The most

genial, the most affectionate, the most loving, and the most lovable

of men. Success had never for an instant spoiled him. His interest

in the Theatre as an Institution--the best picturesqueness of which

may be said to be wholly due to him--was faithful to the last. His

belief in a Play, his delight in one, the ease with which it moved

him to tears or to laughter, were most remarkable evidences of the

heart he must have put into his old theatrical work, and of the

thorough purpose and sincerity with which it must have been done.

The writer was very intimately associated with him in some amateur

plays; and day after day, and night after night, there were the same

unquenchable freshness, enthusiasm, and impressibility in him,

though broken in health, even then.

No Artist can ever have stood by his art with a quieter dignity than

he always did. Nothing would have induced him to lay it at the feet

of any human creature. To fawn, or to toady, or to do undeserved

homage to any one, was an absolute impossibility with him. And yet

his character was so nicely balanced that he was the last man in the

world to be suspected of self-assertion, and his modesty was one of

his most special qualities.

He was a charitable, religious, gentle, truly good man. A genuine

man, incapable of pretence or of concealment. He had been a sailor

once; and all the best characteristics that are popularly attributed

to sailors, being his, and being in him refined by the influences of

his Art, formed a whole not likely to be often seen. There is no

smile that the writer can recall, like his; no manner so naturally

confiding and so cheerfully engaging. When the writer saw him for

the last time on earth, the smile and the manner shone out once

through the weakness, still: the bright unchanging Soul within the

altered face and form.

No man was ever held in higher respect by his friends, and yet his

intimate friends invariably addressed him and spoke of him by a pet

name. It may need, perhaps, the writer's memory and associations to

find in this a touching expression of his winning character, his

playful smile, and pleasant ways. "You know Mrs. Inchbald's story,

Nature and Art?" wrote Thomas Hood, once, in a letter: "What a fine

Edition of Nature and Art is Stanfield!"

Gone! And many and many a dear old day gone with him! But their

memories remain. And his memory will not soon fade out, for he has

set his mark upon the restless waters, and his fame will long be

sounded in the roar of the sea."

THE AGRICULTURAL INTEREST

THE AGRICULTURAL INTEREST"The present Government, having shown itself to be particularly clever in its management of Indictments for Conspiracy, cannot do better, we think (keeping in its administrative eye the pacification of some of its most influential and most unruly supporters), than indict the whole manufacturing interest of the country for a conspiracy against the agricultural interest. As the jury ought to be beyond impeachment, the panel might be chosen among the Duke of Buckingham`s tenants, with the Duke of Buckingham himself as foreman; and, to the end that the country might be quite satisfied with the judge, and have ample security beforehand for his moderation and impartiality, it would be desirable, perhaps, to make such a slight change in the working of the law (a mere nothing to a Conservative Government, bent upon its end), as would enable the question to be tried before an Ecclesiastical Court, with the Bishop of Exeter presiding. The Attorney-General for Ireland, turning his sword into a ploughshare, might conduct the prosecution; and Mr. Cobden and the other traversers might adopt any ground of defence they chose, or prove or disprove anything they pleased, without being embarrassed by the least anxiety or doubt in reference to the verdict.

That the country in general is in a conspiracy against this sacred but unhappy agricultural interest, there can be no doubt. It is not alone within the walls of Covent Garden Theatre, or the Free Trade Hall at Manchester, or the Town Hall at Birmingham, that the cry "Repeal the Corn-laws!" is raised. It may be heard, moaning at night, through the straw-littered wards of Refuges for the Destitute; it may be read in the gaunt and famished faces which make our streets terrible; it is muttered in the thankful grace pronounced by haggard wretches over their felon fare in gaols; it is inscribed in dreadful characters upon the walls of Fever Hospitals; and may be plainly traced in every record of mortality. All of which proves, that there is a vast conspiracy afoot, against the unfortunate agricultural interest.

They who run, even upon railroads, may read of this conspiracy. The old stage-coachman was a farmer`s friend. He wore top-boots, understood cattle, fed his horses upon corn, and had a lively personal interest in malt. The engine-driver`s garb, and sympathies, and tastes belong to the factory. His fustian dress, besmeared with coal-dust and begrimed with soot; his oily hands, his dirty face, his knowledge of machinery; all point him out as one devoted to the manufacturing interest. Fire and smoke, and red-hot cinders follow in his wake. He has no attachment to the soil, but travels on a road of iron, furnace wrought. His warning is not conveyed in the fine old Saxon dialect of our glorious forefathers, but in a fiendish yell. He never cries "ya-hip", with agricultural lungs; but jerks forth a manufactured shriek from a brazen throat.

Where is the agricultural interest represented? From what phase of our social life has it not been driven, to the undue setting up of its false rival?

Are the police agricultural? The watchmen were. They wore woollen nightcaps to a man; they encouraged the growth of timber, by patriotically adhering to staves and rattles of immense size; they slept every night in boxes, which were but another form of the celebrated wooden walls of Old England; they never woke up till it was too late--in which respect you might have thought them very farmers. How is it with the police? Their buttons are made at Birmingham; a dozen of their truncheons would poorly furnish forth a watchman`s staff; they have no wooden walls to repose between; and the crowns of their hats are plated with cast-iron.

Are the doctors agricultural? Let Messrs. Morison and Moat, of the Hygeian establishment at King`s Cross, London, reply. Is it not, upon the constant showing of those gentlemen, an ascertained fact that the whole medical profession have united to depreciate the worth of the Universal Vegetable Medicines? And is this opposition to vegetables, and exaltation of steel and iron instead, on the part of the regular practitioners, capable of any interpretation but one? Is it not a distinct renouncement of the agricultural interest, and a setting up of the manufacturing interest instead?

Do the professors of the law at all fail in their truth to the beautiful maid whom they ought to adore? Inquire of the Attorney General for Ireland. Inquire of that honourable and learned gentleman, whose last public act was to cast aside the grey goose quill, an article of agricultural produce, and take up the pistol, which, under the system of percussion locks, has not even a flint to connect it with farming. Or put the question to a still higher legal functionary, who, on the same occasion, when he should have been a reed, inclining here and there, as adverse gales of evidence disposed him, was seen to be a manufactured image on the seat of Justice, cast by Power, in most impenetrable brass.

The world is too much with us in this manufacturing interest, early and late; that is the great complaint and the great truth. It is not so with the agricultural interest, or what passes by that name. It never thinks of the suffering world, or sees it, or cares to extend its knowledge of it; or, so long as it remains a world, cares anything about it. All those whom Dante placed in the first pit or circle of the doleful regions, might have represented the agricultural interest in the present Parliament, or at quarter sessions, or at meetings of the farmers` friends, or anywhere else.

But that is not the question now. It is conspired against; and we have given a few proofs of the conspiracy, as they shine out of various classes engaged in it. An indictment against the whole manufacturing interest need not be longer, surely, than the indictment in the case of the Crown against O`Connell and others. Mr. Cobden may be taken as its representative--as indeed he is, by one consent already. There may be no evidence; but that is not required. A judge and jury are all that is needed. And the Government know where to find them, or they gain experience to little purpose."

Published in the Morning Chronicle, March 9, 1844

SPEECH: EDINBURGH, JUNE 25, 1841.

SPEECH: EDINBURGH, JUNE 25, 1841. At a public dinner, given in honour of Mr. Dickens:

"If I felt your warm and generous welcome less, I should be better able to thank you. If I could have listened as you have listened to the glowing language of your distinguished Chairman, and if I could have heard as you heard the "thoughts that breathe and words that burn," which he has uttered, it would have gone hard but I should have caught some portion of his enthusiasm, and kindled at his example. But every word which fell from his lips, and every demonstration of sympathy and approbation with which you received his eloquent expressions, renders me unable to respond to his kindness, and leaves me at last all heart and no lips, yearning to respond as I would do to your cordial greeting--possessing, heaven knows, the will, and desiring only to find the way.

The way to your good opinion, favour, and support, has been to me very pleasing--a path strewn with flowers and cheered with sunshine. I feel as if I stood amongst old friends, whom I had intimately known and highly valued. I feel as if the deaths of the fictitious creatures, in which you have been kind enough to express an interest, had endeared us to each other as real afflictions deepen friendships in actual life; I feel as if they had been real persons, whose fortunes we had pursued together in inseparable connexion, and that I had never known them apart from you.

It is a difficult thing for a man to speak of himself or of his works. But perhaps on this occasion I may, without impropriety, venture to say a word on the spirit in which mine were conceived. I felt an earnest and humble desire, and shall do till I die, to increase the stock of harmless cheerfulness. I felt that the world was not utterly to be despised; that it was worthy of living in for many reasons. I was anxious to find, as the Professor has said, if I could, in evil things, that soul of goodness which the Creator has put in them. I was anxious to show that virtue may be found in the bye-ways of the world, that it is not incompatible with poverty and even with rags, and to keep steadily through life the motto, expressed in the burning words of your Northern poet -

"The rank is but the guinea stamp, The man's the gowd for a' that."

And in following this track, where could I have better assurance that I was right, or where could I have stronger assurance to cheer me on than in your kindness on this to me memorable night?

I am anxious and glad to have an opportunity of saying a word in reference to one incident in which I am happy to know you were interested, and still more happy to know, though it may sound paradoxical, that you were disappointed--I mean the death of the little heroine. When I first conceived the idea of conducting that simple story to its termination, I determined rigidly to adhere to it, and never to forsake the end I had in view. Not untried in the school of affliction, in the death of those we love, I thought what a good thing it would be if in my little work of pleasant amusement I could substitute a garland of fresh flowers for the sculptured horrors which disgrace the tomb.

If I have put into my book anything which can fill the young mind with better thoughts of death, or soften the grief of older hearts; if I have written one word which can afford pleasure or consolation to old or young in time of trial, I shall consider it as something achieved--something which I shall be glad to look back upon in after life. Therefore I kept to my purpose, notwithstanding that towards the conclusion of the story, I daily received letters of remonstrance, especially from the ladies. God bless them for their tender mercies! The Professor was quite right when he said that I had not reached to an adequate delineation of their virtues; and I fear that I must go on blotting their characters in endeavouring to reach the ideal in my mind. These letters were, however, combined with others from the sterner sex, and some of them were not altogether free from personal invective. But, notwithstanding, I kept to my purpose, and I am happy to know that many of those who at first condemned me are now foremost in their approbation.

If I have made a mistake in detaining you with this little incident, I do not regret having done so; for your kindness has given me such a confidence in you, that the fault is yours and not mine. I come once more to thank you, and here I am in a difficulty again. The distinction you have conferred upon me is one which I never hoped for, and of which I never dared to dream. That it is one which I shall never forget, and that while I live I shall be proud of its remembrance, you must well know. I believe I shall never hear the name of this capital of Scotland without a thrill of gratitude and pleasure. I shall love while I have life her people, her hills, and her houses, and even the very stones of her streets. And if in the future works which may lie before me you should discern--God grant you may!--a brighter spirit and a clearer wit, I pray you to refer it back to this night, and point to that as a Scottish passage for evermore. I thank you again and again, with the energy of a thousand thanks in each one, and I drink to you with a heart as full as my glass, and far easier emptied, I do assure you."

These are interesting and revealing pieces of writing. When Dickens leaves his world of fiction to enter into his written monologues with an audience he is more direct, more obvious and yet still a craftsman of the written word.

These are interesting and revealing pieces of writing. When Dickens leaves his world of fiction to enter into his written monologues with an audience he is more direct, more obvious and yet still a craftsman of the written word.I want to know where he had the time and energy to do all this writing while maintaining the hectic pace of his life.

Well, Dickens had servants and would not have to do the daily chores, which consume quite a lot of time and nerves. Still, his unbelievable output is impressing. Just imagine that when he was writing PP he also had NN and OT going.

Well, Dickens had servants and would not have to do the daily chores, which consume quite a lot of time and nerves. Still, his unbelievable output is impressing. Just imagine that when he was writing PP he also had NN and OT going.

Letter to a Dr. F. H. Deane

Letter to a Dr. F. H. DeaneCincinnati, Ohio, April 4th, 1842.

My dear Sir,

I have not been unmindful of your request for a moment, but have not been able to think of it until now. I hope my good friends (for whose christian-names I have left blanks in the epitaph) may like what I have written, and that they will take comfort and be happy again. I sail on the 7th of June, and purpose being at the Carlton House, New York, about the 1st. It will make me easy to know that this letter has reached you.

Faithfully yours.

Charles Dickens

This is the Grave of a Little Child,

WHOM GOD IN HIS GOODNESS CALLED TO A BRIGHT ETERNITY

WHEN HE WAS VERY YOUNG.

HARD AS IT IS FOR HUMAN AFFECTION TO RECONCILE ITSELF TO DEATH IN ANY

SHAPE (AND MOST OF ALL, PERHAPS, AT FIRST IN THIS),

HIS PARENTS CAN EVEN NOW BELIEVE THAT IT WILL BE A CONSOLATION

TO THEM THROUGHOUT THEIR LIVES,

AND WHEN THEY SHALL HAVE GROWN OLD AND GRAY,

Always to think of him as a Child in Heaven.

"And Jesus called a little child unto Him, and set him in the midst of them."

He was the Son of Q—— and M—— THORNTON, christened

CHARLES JERKING.

HE WAS BORN ON THE 20TH DAY OF JANUARY, 1841,

AND HE DIED ON THE 12TH DAY OF MARCH, 1842,

having lived only thirteen months and twenty days.

From a speech of Dickens made in America on February 7, 1842:

From a speech of Dickens made in America on February 7, 1842:"Gentlemen, as I have no secrets from you, in the spirit of confidence you have engendered between us, and as I have made a kind of compact with myself that I never will, while I remain in America, omit an opportunity of referring to a topic in which I and all others of my class on both sides of the water are equally interested--equally interested, there is no difference between us, I would beg leave to whisper in your ear two words: INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT. I use them in no sordid sense, believe me, and those who know me best, best know that. For myself, I would rather that my children, coming after me, trudged in the mud, and knew by the general feeling of society that their father was beloved, and had been of some use, than I would have them ride in their carriages, and know by their banker's books that he was rich. But I do not see, I confess, why one should be obliged to make the choice, or why fame, besides playing that delightful REVEIL for which she is so justly celebrated, should not blow out of her trumpet a few notes of a different kind from those with which she has hitherto contented herself.

It was well observed the other night by a beautiful speaker, whose words went to the heart of every man who heard him, that, if there had existed any law in this respect, Scott might not have sunk beneath the mighty pressure on his brain, but might have lived to add new creatures of his fancy to the crowd which swarm about you in your summer walks, and gather round your winter evening hearths.

As I listened to his words, there came back, fresh upon me, that touching scene in the great man's life, when he lay upon his couch, surrounded by his family, and listened, for the last time, to the rippling of the river he had so well loved, over its stony bed. I pictured him to myself, faint, wan, dying, crushed both in mind and body by his honourable struggle, and hovering round him the phantoms of his own imagination--Waverley, Ravenswood, Jeanie Deans, Rob Roy, Caleb Balderstone, Dominie Sampson--all the familiar throng--with cavaliers, and Puritans, and Highland chiefs innumerable overflowing the chamber, and fading away in the dim distance beyond. I pictured them, fresh from traversing the world, and hanging down their heads in shame and sorrow, that, from all those lands into which they had carried gladness, instruction, and delight for millions, they brought him not one friendly hand to help to raise him from that sad, sad bed. No, nor brought him from that land in which his own language was spoken, and in every house and hut of which his own books were read in his own tongue, one grateful dollar-piece to buy a garland for his grave. Oh! if every man who goes from here, as many do, to look upon that tomb in Dryburgh Abbey, would but remember this, and bring the recollection home!

Gentlemen, I thank you again, and once again, and many times to that. You have given me a new reason for remembering this day, which is already one of mark in my calendar, it being my birthday; and you have given those who are nearest and dearest to me a new reason for recollecting it with pride and interest. Heaven knows that, although I should grow ever so gray, I shall need nothing to remind me of this epoch in my life. But I am glad to think that from this time you are inseparably connected with every recurrence of this day; and, that on its periodical return, I shall always, in imagination, have the unfading pleasure of entertaining you as my guests, in return for the gratification you have afforded me to- night."

Kim:

Kim:First came the delightful illustrations that have added so much to our discussions. Now we have Dickens outside of his novels where we met the man on a different level. Thank you.

Great work Kim! I too am constantly astounded at how much he got through. It's not the sheer amount of writing, editing, directing and performing work, but his letters seem to reveal how many other things he was involved in too. And he was always on the move, dashing around the country and abroad.

Great work Kim! I too am constantly astounded at how much he got through. It's not the sheer amount of writing, editing, directing and performing work, but his letters seem to reveal how many other things he was involved in too. And he was always on the move, dashing around the country and abroad.We can deduce from his early childhood why he felt so driven and money-conscious, but I'm wondering if there's something more. He seemed to just burn himself out. Why would he do that?

He was always going, going, going. We know all the writing he did, plus traveling, acting, walking miles every day, on and on. I don't think I've ever read anything about how he would just lean back, put his feet up and rest for awhile. He just never seemed to relax.

He was always going, going, going. We know all the writing he did, plus traveling, acting, walking miles every day, on and on. I don't think I've ever read anything about how he would just lean back, put his feet up and rest for awhile. He just never seemed to relax.

A letter to a Mr. David Dickson who kindly furnishes us with an explanation of the letter dated 10th May. "It was," he says, "in answer to a letter from me, pointing out that the 'Shepherd' in 'Pickwick' was apparently reflecting on the scriptural doctrine of the new birth."

A letter to a Mr. David Dickson who kindly furnishes us with an explanation of the letter dated 10th May. "It was," he says, "in answer to a letter from me, pointing out that the 'Shepherd' in 'Pickwick' was apparently reflecting on the scriptural doctrine of the new birth."1, Devonshire Terrace, York Gate, Regent's Park,

May 10th, 1843.

Sir,

"Permit me to say, in reply to your letter, that you do not understand the intention (I daresay the fault is mine) of that passage in the "Pickwick Papers" which has given you offence. The design of "the Shepherd" and of this and every other allusion to him is, to show how sacred things are degraded, vulgarised, and rendered absurd when persons who are utterly incompetent to teach the commonest things take upon themselves to expound such mysteries, and how, in making mere cant phrases of divine words, these persons miss the spirit in which they had their origin. I have seen a great deal of this sort of thing in many parts of England, and I never knew it lead to charity or good deeds.

Whether the great Creator of the world and the creature of his hands, moulded in his own image, be quite so opposite in character as you believe, is a question which it would profit us little to discuss. I like the frankness and candour of your letter, and thank you for it. That every man who seeks heaven must be born again, in good thoughts of his Maker, I sincerely believe. That it is expedient for every hound to say so in a certain snuffling form of words, to which he attaches no good meaning, I do not believe. I take it there is no difference between us."

Faithfully,

C.D.

Just imagine what it would be like to receive a letter from Charles Dickens. Whether he agreed with or disagreed with me, I would be thrilled.

Just imagine what it would be like to receive a letter from Charles Dickens. Whether he agreed with or disagreed with me, I would be thrilled.

Jean wrote: "That's what I mean. What was wrong with him? I wish we could get a medic today to check him over!"

Jean wrote: "That's what I mean. What was wrong with him? I wish we could get a medic today to check him over!"I wonder what a doctor's diagnosis of him would be in this day and age?

Peter wrote: "Just imagine what it would be like to receive a letter from Charles Dickens. Whether he agreed with or disagreed with me, I would be thrilled."

Peter wrote: "Just imagine what it would be like to receive a letter from Charles Dickens. Whether he agreed with or disagreed with me, I would be thrilled."Didn't he ask everybody to destroy all his letters? I wonder how many actually did - and whether they regretted it ...

Kim wrote: "I wonder what a doctor's diagnosis of him would be in this day and age?"

Kim wrote: "I wonder what a doctor's diagnosis of him would be in this day and age?"Yes, and what are we to make of all those underlinings in his signature?

Little Nell's Funeral Poem

Little Nell's Funeral Poemby Charles Dickens

"And now the bell, - the bell

She had so often heard by night and day

And listened to with solemn pleasure,

E'en as a living voice, -

Rung its remorseless toll for her,

So young, so beautiful, so good.

Decrepit age, and vigorous life,

And blooming youth, and helpless infancy,

Poured forth, - on crutches, in the pride of strength

And health, in the full blush

Of promise, the mere dawn of life, -

To gather round her tomb. Old men were there,

Whose eyes were dim

And senses failing, -

Grandames, who might have died ten years ago,

And still been old, - the deaf, the blind, the lame,

The palsied,

The living dead in many shapes and forms,

To see the closing of this early grave.

What was the death it would shut in,

To that which still could crawl and keep above it!

Along the crowded path they bore her now;

Pure as the new fallen snow

That covered it; whose day on earth

Had been as fleeting.

Under that porch, where she had sat when Heaven

In mercy brought her to that peaceful spot,

She passed again, and the old church

Received her in its quiet shade.

They carried her to one old nook,

Where she had many and many a time sat musing,

And laid their burden softly on the pavement.

The light streamed on it through

The colored window, - a window where the boughs

Of trees were ever rustling

In the summer, and where the birds

Sang sweetly all day long."

Charles Dickens

Kim wrote: "Little Nell's Funeral Poem

Kim wrote: "Little Nell's Funeral Poemby Charles Dickens

"And now the bell, - the bell

She had so often heard by night and day

And listened to with solemn pleasure,

E'en as a living voice, -

Rung its rem..."

Hi Kim

Did Dickens publish this in his magazine or was it sent to an outside publication? I wonder why he was motivated to write this? I had no idea he wrote/published his poetry at all.

We have been discussing how busy a man he was. I guess his journals, novels, travels both within England and to North America and the continent, writing and performing in plays, performances via readings of his novels, and long, long walks was not enough to keep himself busy and amused. And then there is his personal life ...

I'm exhausted simply recounting all the activity ...

I haven't been able to find (yet) when he wrote the Little Nell poem, but here's a few more that do say something of when or why he wrote them:

I haven't been able to find (yet) when he wrote the Little Nell poem, but here's a few more that do say something of when or why he wrote them:"One Lucy Simpkins, of Bremhill (or Bremble), a parish in Wiltshire, had just previously addressed a night meeting of the wives of agricultural labourers in that county, in support of a petition for Free Trade, and her vigorous speech on that occasion inspired Dickens to write ‘The Hymn of the Wiltshire Labourers,’ thus offering an earnest protest against oppression. Concerning the ‘Hymn,’ a writer in a recent issue of Christmas Bells observes: ‘It breathes in every line the teaching of the Sermon on the Mount, the love of the All-Father, the Redemption by His Son, and that love to God and man on which hang all the law and the prophets.’

THE HYMN OF THE WILTSHIRE LABOURERS

‘Don’t you all think that we have a great need to Cry to our God to put it in the hearts of our greassous Queen and her Members of Parlerment to grant us free bread!’

Lucy Simpkins, at Bremhill.

Oh God, who by Thy Prophet’s hand

Didst smite the rocky brake,

Whence water came, at Thy command,

Thy people’s thirst to slake;

Strike, now, upon this granite wall,

Stern, obdurate, and high;

And let some drops of pity fall

For us who starve and die!

The God, who took a little child,

And set him in the midst,

And promised him His mercy mild,

As, by Thy Son, Thou didst:

Look down upon our children dear,

So gaunt, so cold, so spare,

And let their images appear

Where Lords and Gentry are!

Oh God, teach them to feel how we,

When our poor infants droop,

Are weakened in our trust in Thee,

And how our spirits stoop;

For, in Thy rest, so bright and fair,

All tears and sorrows sleep:

And their young looks, so full of care,

Would make Thine Angels weep!

The God, who with His finger drew

The Judgment coming on,

Write, for these men, what must ensue,

Ere many years be gone!

Oh God, whose bow is in the sky,

Let them not brave and dare,

Until they look (too late) on high,

And see an Arrow there!

Oh God, remind them! In the bread

They break upon the knee,

These sacred words may yet be read,

‘In memory of Me!’

Oh God, remind them of His sweet

Compassion for the poor,

And how He gave them Bread to eat,

And went from door to door!"

Charles Dickens

February 1842

"The Christmas number of Household Words for 1856 is especially noteworthy as containing the Hymn of five verses which Dickens contributed to the second chapter. This made a highly favourable impression, and a certain clergyman, the Rev. R. H. Davies, was induced to express to the editor of Household Words his gratitude to the author of these lines for having thus conveyed to innumerable readers such true religious sentiments. In acknowledging the receipt of the letter, Dickens observed that such a mark of approval was none the less gratifying to him because he was himself the author of the Hymn. ‘There cannot be many men, I believe,’ he added, ‘who have a more humble veneration for the New Testament, or a more profound conviction of its all-sufficiency, than I have. If I am ever (as you tell me I am) mistaken on this subject, it is because I discountenance all obtrusive professions of and tradings in religion, as one of the main causes why real Christianity has been retarded in this world; and because my observation of life induces me to hold in unspeakable dread and horror those unseemly squabbles about the letter which drive the spirit out of hundreds of thousands.’—Vide Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens, Book XI. iii."

"The Christmas number of Household Words for 1856 is especially noteworthy as containing the Hymn of five verses which Dickens contributed to the second chapter. This made a highly favourable impression, and a certain clergyman, the Rev. R. H. Davies, was induced to express to the editor of Household Words his gratitude to the author of these lines for having thus conveyed to innumerable readers such true religious sentiments. In acknowledging the receipt of the letter, Dickens observed that such a mark of approval was none the less gratifying to him because he was himself the author of the Hymn. ‘There cannot be many men, I believe,’ he added, ‘who have a more humble veneration for the New Testament, or a more profound conviction of its all-sufficiency, than I have. If I am ever (as you tell me I am) mistaken on this subject, it is because I discountenance all obtrusive professions of and tradings in religion, as one of the main causes why real Christianity has been retarded in this world; and because my observation of life induces me to hold in unspeakable dread and horror those unseemly squabbles about the letter which drive the spirit out of hundreds of thousands.’—Vide Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens, Book XI. iii."A CHILD’S HYMN

"Hear my prayer, O! Heavenly Father,

Ere I lay me down to sleep;

Bid Thy Angels, pure and holy,

Round my bed their vigil keep.

My sins are heavy, but Thy mercy

Far outweighs them every one;

Down before Thy Cross I cast them,

Trusting in Thy help alone.

Keep me through this night of peril

Underneath its boundless shade;

Take me to Thy rest, I pray Thee,

When my pilgrimage is made.

None shall measure out Thy patience

By the span of human thought;

None shall bound the tender mercies

Which Thy Holy Son has bought.

Pardon all my past transgressions,

Give me strength for days to come;

Guide and guard me with Thy blessing

Till Thy Angels bid me home."

Charles Dickens

December 1856

Mouths as HOUSEHOLD WORDS." ---- SHAKESPEARE.

Mouths as HOUSEHOLD WORDS." ---- SHAKESPEARE.HOUSEHOLD WORDS.

A WEEKLY JOURNAL.

CONDUCTED BY CHARLES DICKENS.

No. 1.] SATURDAY, MARCH 30, 1850. [PRICE 2d.

A PRELIMINARY WORD.

"THE name that we have chosen for this publication expresses, generally, the desire we have at heart in originating it.

We aspire to live in the Household affections, and to be numbered among the Household thoughts, of our readers. We hope to be the comrade and friend of many thousands of people, of both sexes, and of all ages and conditions, on whose faces we may never look. We seek to bring into innumerable homes, from the stirring world around us, the knowledge of many social wonders, good and evil, that are not calculated to render any of us less ardently persevering in ourselves, less tolerant of one another, less faithful in the progress of mankind, less thankful for the privilege of living in this summer-dawn of time.

No mere utilitarian spirit, no iron binding of the mind to grim realities, will give a harsh tone to our Household Words. In the bosoms of the young and old, of the well-to-do and of the poor, we would tenderly cherish that light of Fancy which is inherent in the human breast; which, according to its nurture, burns with an inspiring flame, or sinks into a sullen glare, but which (or woe betide that day!) can never be extinguished. To show to all, that in all familiar things, even in those which are repellant on the surface, there is Romance enough, if we will find it out: - to teach the hardest workers at this whirling wheel of toil, that their lot is not necessarily a moody, brutal fact, excluded from the sympathies and graces of imagination; to bring the greater and the lesser in degree, together, upon that wide field, and mutually dispose them to a better acquaintance and a kinder understanding - is one main object of our Household Words.

The mightier inventions of this age are not, to our thinking, all material, but have a kind of souls in their stupendous bodies which may find expression in Household Words. The traveller whom we accompany on his railroad or his steamboat journey, may gain, we hope, some compensation for incidents which these later generations have outlived, in new associations with the Power that bears him onward; with the habitations and the ways of life of crowds of his fellow creatures among whom he passes like the wind; even with the towering chimneys he may see, spirting out fire and smoke upon the prospect. The swart giants, Slaves of the Lamp of Knowledge, have their thousand and one tales, no less than the Genii of the East; and these, in all their wild, grotesque, and fanciful aspects, in all their many phases of endurance, in all their many moving lessons of compassion and consideration, we design to tell.

Our Household Words will not be echoes of the present time alone, but of the past too. Neither will they treat of the hopes, the enterprises, triumphs, joys, and sorrows, of this country only, but, in some degree, of those if every nation upon earth. For nothing can be a source of real interest in one of them, without concerning all the rest.

We have considered what an ambition it is to be admitted into many homes with affection and confidence; to be regarded as a friend by children and old people; to be thought of in affliction and in happiness; to people the sick room with airy shapes 'that give delight and hurt not,' and to be associated with the harmless laughter and the gentle tears of many hearths. We know the great responsibility of such a privilege; its vast reward; the pictures that it conjures up, in hours of solitary labour, of a multitude moved by one sympathy; the solemn hopes which it awakens in the labourer's breast, that he may be free from self-reproach in looking back at last upon his work, and that his name may be remembered in his race in time to come, and borne by the dear objects of his love with pride. The hand that writes these faltering lines, happily associated with some Household Words before to-day, has known enough of such experiences to enter an earnest spirit upon this new task, and with an awakened sense of all that it involves.

Some tillers of the field into which we now come, have been before us, and some are here whose high usefulness we readily acknowledge, and whose company it is an honour to join. But, there are others here - Bastards of the Mountain, draggled fringe on the Red Cap, Panders to the basest passions of the lowest natures - whose existence is a national reproach. And these, we should consider it our highest service to displace.

Thus, we begin our career! The adventurer in the old fairy story, climbing towards the summit of a steep eminence on which the object of his search was stationed, was surrounded by a roar of voices, crying to him, from the stones in the way, to turn back. All the voices we hear, cry Go on! The stones that call to us have sermons in them, as the trees have tongues, as there are books in the running brooks, as there is good in everything! They, and the Time, cry out to us Go on! With a fresh heart, a light step, and a hopeful courage, we begin the journey. The road is not so rough that it need daunt our feet: the way is not so steep that we need stop for breath, and, looking faintly down, be stricken motionless. Go on, is all we hear, Go on! In a glow already, with the air from yonder height upon us, and the inspiriting voices joining in this acclamation, we echo back the cry, and go on cheerily!"

Kim wrote: "Mouths as HOUSEHOLD WORDS." ---- SHAKESPEARE.

Kim wrote: "Mouths as HOUSEHOLD WORDS." ---- SHAKESPEARE.HOUSEHOLD WORDS.

A WEEKLY JOURNAL.

CONDUCTED BY CHARLES DICKENS.

No. 1.] SATURDAY, MARCH 30, 1850. [P..."

Whenever the day arrives that we have completed our reading of The Mystery of Edwin Drood we all can either put our heads together and finish that unfinished novel or start reading Household Words and follow that up with All The Year Round. I think that should keep us going for a few more years. Then again, we could go back to Pickwick.

Finishing Dickens's last novel ... that sounds like the fulfilment of a life, Peter. A very good idea - although there have already been many writers who applied their wits to it. But, as far as I know, there has never been a Pickwick Club setting out with that intention.

Finishing Dickens's last novel ... that sounds like the fulfilment of a life, Peter. A very good idea - although there have already been many writers who applied their wits to it. But, as far as I know, there has never been a Pickwick Club setting out with that intention.

Given Dickens's predilection for ghosts and ghoulies, I would be looking over my shoulder for his shade all the time ;)

Given Dickens's predilection for ghosts and ghoulies, I would be looking over my shoulder for his shade all the time ;)

Tristram wrote: "Finishing Dickens's last novel ... that sounds like the fulfilment of a life, Peter. A very good idea - although there have already been many writers who applied their wits to it. But, as far as I ..."

Tristram wrote: "Finishing Dickens's last novel ... that sounds like the fulfilment of a life, Peter. A very good idea - although there have already been many writers who applied their wits to it. But, as far as I ..."Our Pickwick Club, it can honestly be said, defies description. I like that!

[Sidenote: Mr. Henry Austin, architect and artist married Dickens sister Letitia.]

[Sidenote: Mr. Henry Austin, architect and artist married Dickens sister Letitia.]BROADSTAIRS, _Sunday, September 7th, 1851._

MY DEAR HENRY,

"I am in that state of mind which you may (once) have seen described in the newspapers as "bordering on distraction;" the house given up to me, the fine weather going on (soon to break, I daresay), the painting season oozing away, my new book waiting to be born, and

NO WORKMEN ON THE PREMISES,

along of my not hearing from you!! I have torn all my hair off, and constantly beat my unoffending family. Wild notions have occurred to me of sending in my own plumber to do the drains. Then I remember that you have probably written to prepare _your_ man, and restrain my audacious hand. Then Stone presents himself, with a most exasperatingly mysterious visage, and says that a rat has appeared in the kitchen, and it's his opinion (Stone's, not the rat's) that the drains want "compo-ing;" for the use of which explicit language I could fell him without remorse. In my horrible desire to "compo" everything, the very postman becomes my enemy because he brings no letter from you; and, in short, I don't see what's to become of me unless I hear from you to-morrow, which I have not the least expectation of doing.

Going over the house again, I have materially altered the plans--abandoned conservatory and front balcony--decided to make Stone's painting-room the drawing-room (it is nearly six inches higher than the room below), to carry the entrance passage right through the house to a back door leading to the garden, and to reduce the once intended drawing-room--now school-room--to a manageable size, making a door of communication between the new drawing-room and the study. Curtains and carpets, on a scale of awful splendour and magnitude, are already in preparation, and still--still--

NO WORKMEN ON THE PREMISES.

To pursue this theme is madness. Where are you? When are you coming home? Where is the man who is to do the work? Does he know that an army of artificers must be turned in at once, and the whole thing finished out of hand? O rescue me from my present condition. Come up to the scratch, I entreat and implore you!

I send this to Laetitia to forward,

Being, as you well know why,

Completely floored by N. W., I

_Sleep_.

I hope you may be able to read this. My state of mind does not admit of coherence."

Ever affectionately.

C.D.

P.S.--NO WORKMEN ON THE PREMISES!

Ha! ha! ha! (I am laughing demoniacally.)

Aren't these great? It's like you're looking over his shoulder! Thanks so much for posting them Kim :)

Aren't these great? It's like you're looking over his shoulder! Thanks so much for posting them Kim :)

Jean wrote: "Aren't these great? It's like you're looking over his shoulder! Thanks so much for posting them Kim :)"

Jean wrote: "Aren't these great? It's like you're looking over his shoulder! Thanks so much for posting them Kim :)"A new picture! Did I miss an earlier post? Does the baby's name have any Dickens connections?

Congratulations!

Kim wrote: "[Sidenote: Mr. Henry Austin, architect and artist married Dickens sister Letitia.]

Kim wrote: "[Sidenote: Mr. Henry Austin, architect and artist married Dickens sister Letitia.]BROADSTAIRS, _Sunday, September 7th, 1851._

MY DEAR HENRY,

"I am in that state of mind which you may (once) h..."

It's nice to know that workmen apparently didn't show up in the Victorian period as well. And to think I was taking all the non-arrivals personally ... :-(

LOL Peter - unfortunately not! She is called "Lauren" and is the first "family" baby for a long time - and a little poppet! Link here

LOL Peter - unfortunately not! She is called "Lauren" and is the first "family" baby for a long time - and a little poppet! Link hereOh and the last picture along is yesterday when I actually met up with a Goodreads friend in real life! Fantastic :) Wish we all could ...

Thursday, December 9th, 1852.

Thursday, December 9th, 1852.My dear Wills,

"I am driven mad by dogs, who have taken it into their accursed heads to assemble every morning in the piece of ground opposite, and who have barked this morning for five hours without intermission; positively rendering it impossible for me to work, and so making what is really ridiculous quite serious to me. I wish, between this and dinner, you would send John to see if he can hire a gun, with a few caps, some powder, and a few charges of small shot. If you duly commission him with a card, he can easily do it. And if I get those implements up here to-night, I'll be the death of some of them to-morrow morning."

Ever faithfully.

C.D.

Kim wrote: "Thursday, December 9th, 1852.

Kim wrote: "Thursday, December 9th, 1852.My dear Wills,

"I am driven mad by dogs, who have taken it into their accursed heads to assemble every morning in the piece of ground opposite, and who have barked t..."

Kim. Ignore what this letter suggests. I know Dickens would love your dog.

I too am hoping that this was tongue-in-cheek. Give his well-observed and sympathetic portrait of Diogenes, in Dombey and Son, I think he must have loved dogs really :)

I too am hoping that this was tongue-in-cheek. Give his well-observed and sympathetic portrait of Diogenes, in Dombey and Son, I think he must have loved dogs really :)

Anyone as brilliant as Dickens would have to love dogs. I can't remember if he had one, I'll have to go look. :-)

Anyone as brilliant as Dickens would have to love dogs. I can't remember if he had one, I'll have to go look. :-)

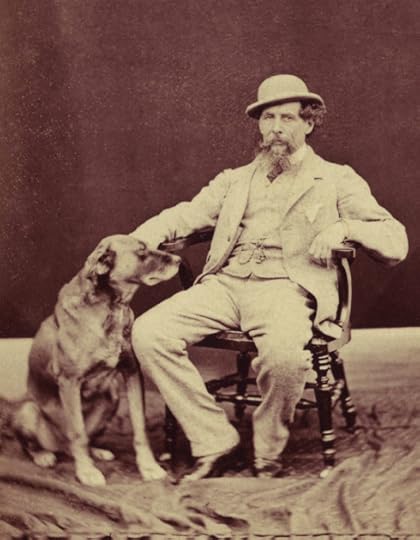

"At Gad’s-Hill Dickens surrounded himself with a pack of wonderful dogs. Two were usually tied to either side of the entrance gate to protect the house from the ruffians and vagabonds that tramped down the well-traveled road. Turk, intelligent and affectionate, was Dickens’s favorite. In this wonderful photograph they appear well matched. Both look noble and dignified. Dickens grieved terribly when Turk died in a railway accident, not long after Dickens’s own traumatic experience in a railway crash at Staplehurst in 1865."

From a letter Dickens wrote, I don't know to who, after returning from his trip to America:

From a letter Dickens wrote, I don't know to who, after returning from his trip to America:"As you ask me about the dogs, I begin with them. The two Newfoundland dogs coming to meet me, with the usual carriage and the usual driver, and beholding me coming in my usual dress out at the usual door, it struck me that their recollection of my having been absent for any unusual time was at once cancelled. They behaved (they are both young dogs) exactly in their usual manner; coming behind the basket phaeton as we trotted along, and lifting their heads to have their ears pulled,—a special attention which they receive from no one else. But when I drove into the stable-yard, Linda (the St. Bernard) was greatly excited, weeping profusely, and throwing herself on her back that she might caress my foot with her great fore-paws. M.'s little dog, too, Mrs. Bouncer, barked in the greatest agitation, on being called down and asked, 'Who is this?' tearing round and round me like the dog in the Faust outlines."

Kim - Thanks - that's fascinating!

Kim - Thanks - that's fascinating! I'm not very sure about the lives of those dogs tied to gateposts though - hope they got a bit of exercise sometimes, but I guess if people were always passing by then at least they weren't lonely !

I am going to save this great photo of Dickens. He obviously loved dosgs :)

Kim

KimI have never seen this picture before. It's great. The letters give us further insight into Dickens as well.

I really love learning about all these facets of his life. Thanks.

Kim wrote: "[To Mr. William Harrison Ainsworth.]

Kim wrote: "[To Mr. William Harrison Ainsworth.]DEVONSHIRE TERRACE, _October 13th, 1843._

MY DEAR AINSWORTH,

"I want very much to see you, not having had that old pleasure for a long

time. I am at this mo..."

Kim: You are a true Dickensian. I noticed that the date on the Dickens letter was October, 13, 1843. Today is October 13, 2015.

So to Dickens I offer a belated "get well soon" and to you a tip of my virtual hat for your timely post. :-)

A letter to a Mr. Clarkson Stanfield, a prominent English marine painter and friend of Dickens:

A letter to a Mr. Clarkson Stanfield, a prominent English marine painter and friend of Dickens:H.M.S. Tavistock, January 2nd, 1853.

"Yoho, old salt! Neptun' ahoy! You don't forget, messmet, as you was to meet Dick Sparkler and Mark Porpuss on the fok'sle of the good ship Owssel Words, Wednesday next, half-past four? Not you; for when did Stanfell ever pass his word to go anywheers and not come! Well. Belay, my heart of oak, belay! Come alongside the Tavistock same day and hour, 'stead of Owssel Words. Hail your shipmets, and they'll drop over the side and join you, like two new shillings a-droppin' into the purser's pocket. Damn all lubberly boys and swabs, and give me the lad with the tarry trousers, which shines to me like di'mings bright!"

A Child’s Dream of a Star

A Child’s Dream of a Star By Charles Dickens

"THERE was once a child, and he strolled about a good deal, and thought of a number of things. He had a sister, who was a child, too, and his constant companion. These two used to wonder all day long. They wondered at the beauty of the flowers; they wondered at the height and blueness of the sky; they wondered at the depth of the bright water; they wondered at the goodness and the power of God who made the lovely world.

They used to say to one another sometimes, Supposing all the children upon earth were to die, would the flowers, and the water, and the sky be sorry? They believed they would be sorry. For, said they, the buds are the children of the flowers, and the little playful streams that gambol down the hillsides are the children of the water; and the smallest bright specks playing at hide-and-seek in the sky all night, must surely be the children of the stars; and they would all be grieved to see their playmates, the children of men, no more.

There was one clear shining star that used to come out in the sky before the rest, near the church spire, above the graves. It was larger and more beautiful, they thought, than all others, and every night they watched for it, standing hand in hand at the window. Whoever saw it first, cried out, “I see the star!” And often they cried out both together, knowing so well when it would rise, and where. So they grew to be such friends with it, that before lying down in their beds, they always looked out once again, to bid it good night; and when they were turning around to sleep, they used to say, “God bless the star!”

But while she was very young, oh, very, very young, the sister drooped, and came to be so weak that she could no longer stand in the window at night; and then the child looked sadly out by himself, and when he saw the star, turned round and said to the patient, pale face on the bed, “I see the star!” and then a smile would come upon the face, and a little weak voice used to say, “God bless my brother and the star!”

And so the time came, all too soon! when the child looked out alone, and when there was no face on the bed; and when there was a little grave among the graves, not there before; and when the star made long rays down toward him, as he saw it through his tears.

Now, these rays were so bright, and they seemed to make such a shining way from earth to heaven, that when the child went to his solitary bed, he dreamed about the star; and dreamed that, lying where he was, he saw a train of people taken up that sparkling road by angels. And the star, opening, showed him a great world of light, where many more such angels waited to receive them.

All these angels who were waiting turned their beaming eyes upon the people who were carried up into the star; and some came out from the long rows in which they stood, and fell upon the people’s necks, and kissed them tenderly, and went away with them down avenues of light, and were so happy in their company, that lying in his bed he wept for joy.

But there were many angels who did not go with them, and among them one he knew. The patient face that once had lain upon the bed was glorified and radiant, but his heart found out his sister among all the host.

His sister’s angel lingered near the entrance of the star, and said to the leader among those who had brought the people thither

“Is my brother come?”

And he said, “No.”

She was turning hopefully away, when the child stretched out his arms, and cried, “O sister, I am here! Take me!” And then she turned her beaming eyes upon him and it was night; and the star was shining into the room, making long rays down toward him as he saw it through his tears.

From that hour forth the child looked out upon the star as on the home he was to go to, when his time should come; and he thought that he did not belong to the earth alone, but to the star, too, because of his sister’s angel gone before.

There was a baby born to be a brother to the child; and while he was so little that he never yet had spoken word, he stretched his tiny form out on his bed and died.

Again the child dreamed of the opened star, and of the company of angels, and the train of people, and the rows of angels with their beaming eyes all turned upon those people’s faces.

Said his sister’s angel to the leader:

“Is my brother come?”

And he said, “Not that one, but another.”

As the child beheld his brother’s angel in her arms, he cried: “O sister, I am here! Take me!” And she turned and smiled upon him, and the star was shining.

He grew to be a young man, and was busy at his books, when an old servant came to him and said:

“Thy mother is no more. I bring her blessing on her darling son!”

Again at night he saw the star, and all that former company. Said his sister’s angel to the leader:

“Is my brother come?”

And he said, “Thy mother!”

A mighty cry of joy went forth through all the star, because the mother was reunited to her two children. And he stretched out his arms and cried: “O mother, sister, and brother, I am here! Take me!” And they answered him, “Not yet.” And the star was shining.

He grew to be a man whose hair was turning gray, and he was sitting in his chair by the fireside, heavy with grief, and with his face bedewed with tears, when the star opened once again.

Said his sister’s angel to the leader, “Is my brother come?”

And he said, “Nay, but his maiden daughter.”

And the man who had been the child saw his daughter, newly lost to him, a celestial creature among those three, and he said, “My daughter’s head is on my sister’s bosom, and her arm is round my mother’s neck, and at her feet there is the baby of old time, and I can bear the parting from her, God be praised!”

And the star was shining.

Thus the child came to be an old man, and his once smooth face was wrinkled, and his steps were slow and feeble, and his back was bent. And one night as he lay upon his bed, his children standing round, he cried, as he had cried so long ago:—

“I see the star!”

They whispered one another, “He is dying.”

And he said: “I am. My age is falling from me like a garment, and I move toward the star as a child. And, O my Father, now I thank thee that it has so often opened to receive those dear ones who await me!”

And the star was shining; and it shines upon his grave."

It is a rare artist who can paint or write something that is, at once, so powerful and yet so gentle.

It is a rare artist who can paint or write something that is, at once, so powerful and yet so gentle.

The Child's Story

The Child's StoryCharles Dickens

"Once upon a time, a good many years ago, there was a traveller, and he set out upon a journey. It was a magic journey, and was to seem very long when he began it, and very short when he got half way through.

He travelled along a rather dark path for some little time, without meeting anything, until at last he came to a beautiful child. So he said to the child, “What do you do here?” And the child said, “I am always at play. Come and play with me!”

So, he played with that child, the whole day long, and they were very merry. The sky was so blue, the sun was so bright, the water was so sparkling, the leaves were so green, the flowers were so lovely, and they heard such singing-birds and saw so many butteries, that everything was beautiful. This was in fine weather. When it rained, they loved to watch the falling drops, and to smell the fresh scents. When it blew, it was delightful to listen to the wind, and fancy what it said, as it came rushing from its home — where was that, they wondered! — whistling and howling, driving the clouds before it, bending the trees, rumbling in the chimneys, shaking the house, and making the sea roar in fury. But, when it snowed, that was best of all; for, they liked nothing so well as to look up at the white flakes falling fast and thick, like down from the breasts of millions of white birds; and to see how smooth and deep the drift was; and to listen to the hush upon the paths and roads.

They had plenty of the finest toys in the world, and the most astonishing picture-books: all about scimitars and slippers and turbans, and dwarfs and giants and genii and fairies, and blue- beards and bean-stalks and riches and caverns and forests and Valentines and Orsons: and all new and all true.

But, one day, of a sudden, the traveller lost the child. He called to him over and over again, but got no answer. So, he went upon his road, and went on for a little while without meeting anything, until at last he came to a handsome boy. So, he said to the boy, “What do you do here?” And the boy said, “I am always learning. Come and learn with me.”

So he learned with that boy about Jupiter and Juno, and the Greeks and the Romans, and I don’t know what, and learned more than I could tell — or he either, for he soon forgot a great deal of it. But, they were not always learning; they had the merriest games that ever were played. They rowed upon the river in summer, and skated on the ice in winter; they were active afoot, and active on horseback; at cricket, and all games at ball; at prisoner’s base, hare and hounds, follow my leader, and more sports than I can think of; nobody could beat them. They had holidays too, and Twelfth cakes, and parties where they danced till midnight, and real Theatres where they saw palaces of real gold and silver rise out of the real earth, and saw all the wonders of the world at once. As to friends, they had such dear friends and so many of them, that I want the time to reckon them up. They were all young, like the handsome boy, and were never to be strange to one another all their lives through.

Still, one day, in the midst of all these pleasures, the traveller lost the boy as he had lost the child, and, after calling to him in vain, went on upon his journey. So he went on for a little while without seeing anything, until at last he came to a young man. So, he said to the young man, “What do you do here?” And the young man said, “I am always in love. Come and love with me.”

So, he went away with that young man, and presently they came to one of the prettiest girls that ever was seen — just like Fanny in the corner there — and she had eyes like Fanny, and hair like Fanny, and dimples like Fanny’s, and she laughed and coloured just as Fanny does while I am talking about her. So, the young man fell in love directly — just as Somebody I won’t mention, the first time he came here, did with Fanny. Well! he was teased sometimes — just as Somebody used to be by Fanny; and they quarrelled sometimes — just as Somebody and Fanny used to quarrel; and they made it up, and sat in the dark, and wrote letters every day, and never were happy asunder, and were always looking out for one another and pretending not to, and were engaged at Christmas-time, and sat close to one another by the fire, and were going to be married very soon — all exactly like Somebody I won’t mention, and Fanny!

But, the traveller lost them one day, as he had lost the rest of his friends, and, after calling to them to come back, which they never did, went on upon his journey. So, he went on for a little while without seeing anything, until at last he came to a middle-aged gentleman. So, he said to the gentleman, “What are you doing here?” And his answer was, “I am always busy. Come and be busy with me!”

So, he began to be very busy with that gentleman, and they went on through the wood together. The whole journey was through a wood, only it had been open and green at first, like a wood in spring; and now began to be thick and dark, like a wood in summer; some of the little trees that had come out earliest, were even turning brown. The gentleman was not alone, but had a lady of about the same age with him, who was his Wife; and they had children, who were with them too. So, they all went on together through the wood, cutting down the trees, and making a path through the branches and the fallen leaves, and carrying burdens, and working hard.

Sometimes, they came to a long green avenue that opened into deeper woods. Then they would hear a very little, distant voice crying, “Father, father, I am another child! Stop for me!” And presently they would see a very little figure, growing larger as it came along, running to join them. When it came up, they all crowded round it, and kissed and welcomed it; and then they all went on together.

Sometimes, they came to several avenues at once, and then they all stood still, and one of the children said, “Father, I am going to sea,” and another said, “Father, I am going to India,” and another, “Father, I am going to seek my fortune where I can,” and another, “Father, I am going to Heaven!” So, with many tears at parting, they went, solitary, down those avenues, each child upon its way; and the child who went to Heaven, rose into the golden air and vanished.

Whenever these partings happened, the traveller looked at the gentleman, and saw him glance up at the sky above the trees, where the day was beginning to decline, and the sunset to come on. He saw, too, that his hair was turning grey. But, they never could rest long, for they had their journey to perform, and it was necessary for them to be always busy.

At last, there had been so many partings that there were no children left, and only the traveller, the gentleman, and the lady, went upon their way in company. And now the wood was yellow; and now brown; and the leaves, even of the forest trees, began to fall.

So, they came to an avenue that was darker than the rest, and were pressing forward on their journey without looking down it when the lady stopped.

“My husband,” said the lady. “I am called.”

They listened, and they heard a voice a long way down the avenue, say, “Mother, mother!”

It was the voice of the first child who had said, “I am going to Heaven!” and the father said, “I pray not yet. The sunset is very near. I pray not yet!”

But, the voice cried, “Mother, mother!” without minding him, though his hair was now quite white, and tears were on his face.

Then, the mother, who was already drawn into the shade of the dark avenue and moving away with her arms still round his neck, kissed him, and said, “My dearest, I am summoned, and I go!” And she was gone. And the traveller and he were left alone together.

And they went on and on together, until they came to very near the end of the wood: so near, that they could see the sunset shining red before them through the trees.

Yet, once more, while he broke his way among the branches, the traveller lost his friend. He called and called, but there was no reply, and when he passed out of the wood, and saw the peaceful sun going down upon a wide purple prospect, he came to an old man sitting on a fallen tree. So, he said to the old man, “What do you do here?” And the old man said with a calm smile, “I am always remembering. Come and remember with me!”

So the traveller sat down by the side of that old man, face to face with the serene sunset; and all his friends came softly back and stood around him. The beautiful child, the handsome boy, the young man in love, the father, mother, and children: every one of them was there, and he had lost nothing. So, he loved them all, and was kind and forbearing with them all, and was always pleased to watch them all, and they all honoured and loved him. And I think the traveller must be yourself, dear Grandfather, because this what you do to us, and what we do to you."

This is from the book Charles Dickens and his friends by by W. Teignmouth ShoreW. Teignmouth Shore, published in 1909. This is from Chapter 6, titled "The Man".

This is from the book Charles Dickens and his friends by by W. Teignmouth ShoreW. Teignmouth Shore, published in 1909. This is from Chapter 6, titled "The Man"."What tremendously high spirits ran riot in those early Victorian Days! The men seem to have been just jolly grown up boys, overflowing with animal spirits. There was no morbidity of decadence then! The flowers were always blooming in the spring, save when holly and mistletoe, good will and good cheer, ruled the roast at winter-tide. Charles Dickens was one of the brightest of them all, a splendidly handsome young fellow, a good forehead above a nose with somewhat full nostrils; eyes of quite extraordinary brilliancy, a characteristic to the day of his death; a somewhat prominent, sensitive mouth. Equally true then was what Sergeant Ballantine wrote at a later period; "There was a brightness and geniality about him," says the Sergeant, "that greatly fascinated his companions. His laugh was so cheery, and he seemed so thoroughly to enter into the feelings of those around him. He told a story well and never prosily; he was a capital listener; and in conversation was not in the slightest degree dictatorial."

With all his vivacity and apparent boyishness he was extremely methodical in all his ways.

"No writer never lived," says an American friend; in a somewhat sweeping way, "whose method was more exact, whose industry was more constant, and whose punctuality was more marked", and his daughter "Mamie" wrote of him, "There never existed, I think, in all the world, a more thoroughly tidy or methodical creature in all the world than my father. He was tidy in every way - in his mind, in his handsome and graceful person, in his work, in keeping his writing-table drawers, in his large correspondence, in fact in his whole life." He could be a fidget, too, as for example with regards for the furniture of a room in a hotel, at which he might be spending only a single night - rearranging it all, and turning the bed north and south - to meet the views of the electrical currents of the earth!

What astonishing vitality he had; his way of resting a tired brain was to indulge in violent bodily exercise; a "fifteen-mile ride out", with a friend, "ditto in, and a lunch on the road," topping up with dinner at six o'clock in Doughty Street. He would write to Forster, "you don't feel disposed, do you, to muffle yourself up, and start off with me for a good brisk walk over Hampstead Heath? I know a good 'ous there where we can have a red- hot chop there for dinner, and a glass of good wine," the "'ous" being the far famed Jack's Straw Castle."

The Ivy Green

The Ivy Green"Oh, a dainty plant is the Ivy green,

That creepeth o'er ruins old!

Of right choice food are his meals, I ween,

In his cell so lone and cold.

The wall must be crumbled, the stone decayed,

To pleasure his dainty whim:

And the mouldering dust that years have made

Is a merry meal for him.

Creeping where no life is seen,

A rare old plant is the Ivy green.

Fast he stealeth on, though he wears no wings,

And a staunch old heart has he.

How closely he twineth, how tight he clings

To his friend the huge Oak Tree!

And slyly he traileth along the ground,

And his leaves he gently waves,

As he joyously hugs and crawleth round

The rich mould of dead men's graves.

Creeping where grim death hath been,

A rare old plant is the Ivy green.

Whole ages have fled and their works decayed,

And nations have scattered been;

But the stout old Ivy shall never fade,

From its hale and hearty green.

The brave old plant, in its lonely days,

Shall fatten upon the past:

For the stateliest building man can raise

Is the Ivy's food at last.

Creeping on where time has been,

A rare old plant is the Ivy green."

Charles Dickens

Books mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens and his friends (other topics)Dombey and Son (other topics)

FIVE NEW POINTS OF CRIMINAL LAW

"The existing Criminal Law has been found in trials for Murder, to be so exceedingly hasty, unfair, and oppressive--in a word, to be so very objectionable to the amiable persons accused of that thoughtless act--that it is, we understand, the intention of the Government to bring in a Bill for its amendment. We have been favoured with an outline of its probable provisions.

It will be grounded on the profound principle that the real offender is the Murdered Person; but for whose obstinate persistency in being murdered, the interesting fellow-creature to be tried could not have got into trouble.

Its leading enactments may be expected to resolve themselves under the following heads:

1. There shall be no judge. Strong representations have been made by highly popular culprits that the presence of this obtrusive character is prejudicial to their best interests. The Court will be composed of a political gentleman, sitting in a secluded room commanding a view of St. James's Park, who has already more to do than any human creature can, by any stretch of the human imagination, be supposed capable of doing.

2. The jury to consist of Five Thousand Five Hundred and Fifty-five Volunteers.

3. The jury to be strictly prohibited from seeing either the accused or the witnesses. They are not to be sworn. They are on no account to hear the evidence. They are to receive it, or such representations of it, as may happen to fall in their way; and they will constantly write letters about it to all the Papers.

4. Supposing the trial to be a trial for Murder by poisoning, and supposing the hypothetical case, or the evidence, for the prosecution to charge the administration of two poisons, say Arsenic and Antimony; and supposing the taint of Arsenic in the body to be possible but not probable, and the presence of Antimony in the body, to be an absolute certainty; it will then become the duty of the jury to confine their attention solely to the Arsenic, and entirely to dismiss the Antimony from their minds.

5. The symptoms preceding the death of the real offender (or Murdered Person) being described in evidence by medical practitioners who saw them, other medical practitioners who never saw them shall be required to state whether they are inconsistent with certain known diseases--but, THEY SHALL NEVER BE ASKED WHETHER THEY ARE NOT EXACTLY CONSISTENT WITH THE ADMINISTRATION OF POISON. To illustrate this enactment in the proposed Bill by a case:- A raging mad dog is seen to run into the house where Z lives alone, foaming at the mouth. Z and the mad dog are for some time left together in that house under proved circumstances, irresistibly leading to the conclusion that Z has been bitten by the dog. Z is afterwards found lying on his bed in a state of hydrophobia, and with the marks of the dog's teeth. Now, the symptoms of that disease being identical with those of another disease called Tetanus, which might supervene on Z's running a rusty nail into a certain part of his foot, medical practitioners who never saw Z, shall bear testimony to that abstract fact, and it shall then be incumbent on the Registrar-General to certify that Z died of a rusty nail.

It is hoped that these alterations in the present mode of procedure will not only be quite satisfactory to the accused person (which is the first great consideration), but will also tend, in a tolerable degree, to the welfare and safety of society. For it is not sought in this moderate and prudent measure to be wholly denied that it is an inconvenience to Society to be poisoned overmuch."

published in "All The Year Round" SEPTEMBER 24, 1859