Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

This topic is about

The Decameron

Boccaccio's Decameron

>

9/22-9/28: Ninth Day, Introduction & Stories 1-5

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kris

(new)

-

added it

Apr 14, 2014 09:30AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

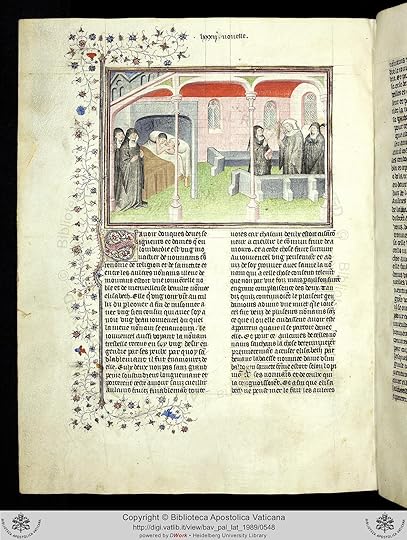

Illustrations - Day IX Story 1

Illustrations - Day IX Story 1

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Rinuccio Palermini au cimetière. Rinuccio Palermini fuyant la garde

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

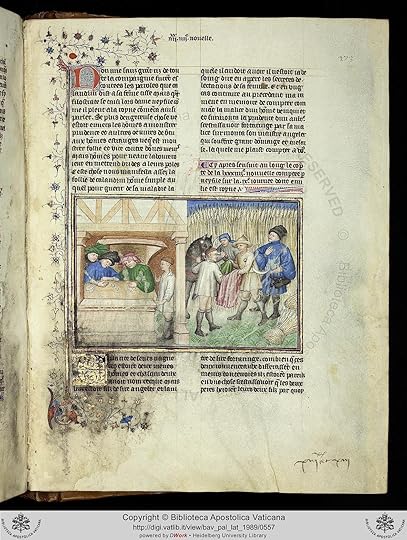

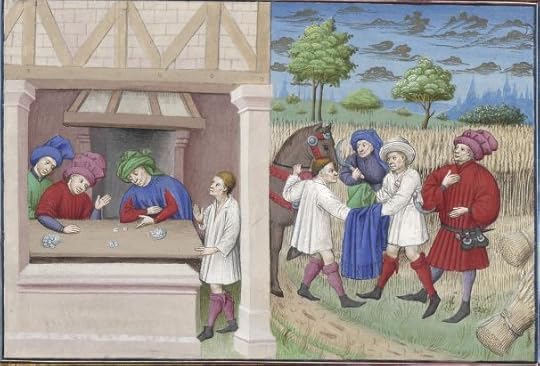

Illustrations - Day IX Story 2

Illustrations - Day IX Story 2

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Isabetta & son amant. Isabetta devant l'abbesse

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

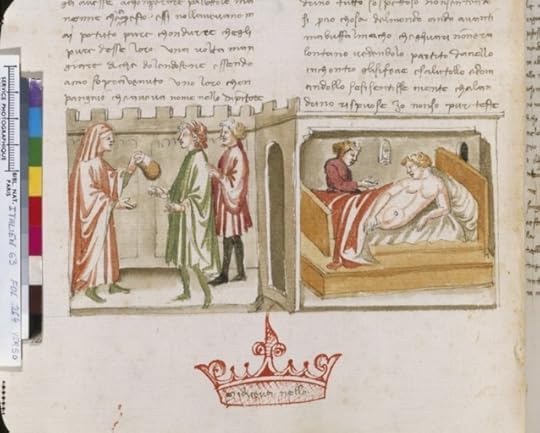

Illustrations - Day IX Story 3

Illustrations - Day IX Story 3

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Calandrino malade imaginaire. Couronne

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

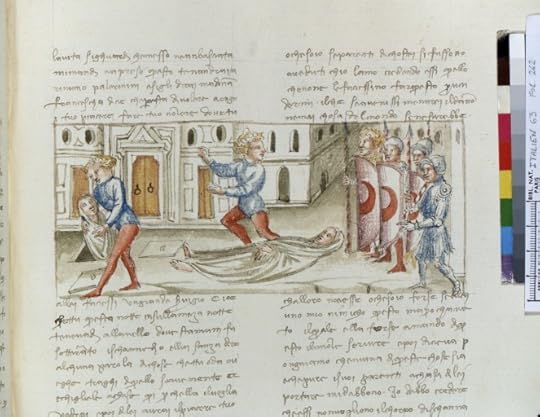

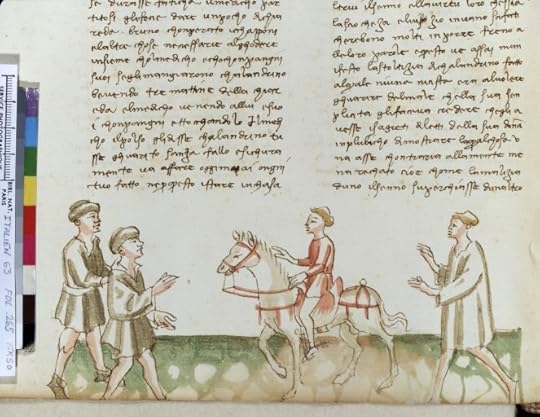

Illustrations - Day IX Story 4

Illustrations - Day IX Story 4

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Cecco Angiolieri pris pour un voleur

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day IX Story 5

Illustrations - Day IX Story 5

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Calandrino & Niccolosa

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Thank you Book Portrait!

Second tale (IX, 2)

Elissa is the narrator of this tale which was either taken from a fabliau by Jean de Condé written between 1313 and 1337, or from a story about Saint Jerome in The Golden Legend, written about 1260. The former was the more likely source for Boccaccio.

The Golden Legend (Latin: Legenda aurea or Legenda sanctorum) is a collection of hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine that became a late medieval bestseller. More than a thousand manuscripts of the text have survived. It was likely compiled around the year 1260, although the text was added to over the centuries

The Old French fabliaux supply a high quotient of analogues to the hundred stories in Boccaccio's Decameron. Approximately one fourth of the novelle in the collection borrow from the fabliaux tradition. Marcus Landau cites several fabliaux in his study of sources for the Decameron, and Vittore Branca mentions about twenty-four fabliaux titles in the notes to his edition of the Decameron.2 More recently, Luciano Rossi has stated that twenty of the tales in the Decameron are demonstrably related to fabliaux sources, but Rossi does not provide a list of these fabliaux or their corresponding novelle.3 While the fabliaux's influence arguably extends beyond this figure, Decameron IX.2 is, nevertheless, an exceptional case among the novelle related to fabliaux, as it takes a single fabliau, composed by Jean de Condé, and entitled, La Nonete, as its primary source.

Scholars have long agreed that Boccaccio was in some way familiar with La Nonete. Branca cites two fabliaux as well known, Old French antecedents of novella IX.2: La Nonete and the anonymous Les Braies au cordelier.4 All three of these tales present the popular theme of the brache del prete ("the priest's breeches"), a humorous motif suggesting the lasciviousness of the clergy that was common to a variety of genres in medieval literature.5 Landau, on the other hand, cites the miraculous tale "L'abbesse qui fu grosse" ("The Abbess Who Was Pregnant"), which vaguely resembles Boccaccio's story through its mention of hypocrisy among the clergy, but makes no use of the brache del prete topos.6 Since the topos is the same, Decameron IX.2 may be considered much more closely connected to one of the fabliaux than to the miraculous tale of the abbess.

Not included in the list enumerated by Branca is the thematically similar fabliau, Les Braies le priestre, which was also composed by Jean de Condé. Although this fabliau and the anonymous Les Braies au cordelier both make use of the theme of the brache del prete, they are not necessarily sources for Boccaccio's novella.7 This literary motif usually involves the theft or misplacement of a cleric's pants, with its implications of sexual relations. An example from the Legenda Aurea (number 146)—also cited by Branca—gives an anecdote from the life of St. Jerome whose clothes are stolen by his fellow monks and replaced by women's clothing. When he mistakenly dresses in these clothes, the other monks assume that he has been sleeping with a woman and that he erringly put on her clothing in the dark. There are, however, no breeches in this example of the topos. In Les Braies au cordelier, a man, having surprised his wife with a clerk, mistakes the clerk's pants for his own the next morning, and his delayed discovery of the mistake is the evidence of his wife's infidelity. Despite the similarities of dressing in the dark and mistaken clothing, these two examples in fact present two different types of stories: the former results in cross-dressing, while the latter involves a mere substitution of the cleric's pants for those of another man. The two distinct narratives which emerge from the theme of the brache del prete do not alter the implication of sexual (mis)behavior, but they do allow us to recognize that the anecdote about St. Jerome, which involves an example of cross-dressing, and Les Braies au cordelier, which consists of a substitution, belong to two discrete narrative traditions. Decameron IX.2 represents a combination of these two traditions, a mixture of cross-dressing and mistaken breeches. Of the possible sources for Decameron IX.2, only La Nonete demonstrates the same combination of the two traditions. Thus, La Nonete and Decameron IX.2 share more than similar plots and structures, but in fact share the same "textual nucleus."8 For this reason, La Nonete is the most probable source for Boccaccio's novella.

The basic plots of Decameron IX.2 and La Nonete show a remarkable number of similarities. In both stories, a young nun (or novice) is caught with a man. When the other nuns who caught her go to...

Second tale (IX, 2)

Elissa is the narrator of this tale which was either taken from a fabliau by Jean de Condé written between 1313 and 1337, or from a story about Saint Jerome in The Golden Legend, written about 1260. The former was the more likely source for Boccaccio.

The Golden Legend (Latin: Legenda aurea or Legenda sanctorum) is a collection of hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine that became a late medieval bestseller. More than a thousand manuscripts of the text have survived. It was likely compiled around the year 1260, although the text was added to over the centuries

The Old French fabliaux supply a high quotient of analogues to the hundred stories in Boccaccio's Decameron. Approximately one fourth of the novelle in the collection borrow from the fabliaux tradition. Marcus Landau cites several fabliaux in his study of sources for the Decameron, and Vittore Branca mentions about twenty-four fabliaux titles in the notes to his edition of the Decameron.2 More recently, Luciano Rossi has stated that twenty of the tales in the Decameron are demonstrably related to fabliaux sources, but Rossi does not provide a list of these fabliaux or their corresponding novelle.3 While the fabliaux's influence arguably extends beyond this figure, Decameron IX.2 is, nevertheless, an exceptional case among the novelle related to fabliaux, as it takes a single fabliau, composed by Jean de Condé, and entitled, La Nonete, as its primary source.

Scholars have long agreed that Boccaccio was in some way familiar with La Nonete. Branca cites two fabliaux as well known, Old French antecedents of novella IX.2: La Nonete and the anonymous Les Braies au cordelier.4 All three of these tales present the popular theme of the brache del prete ("the priest's breeches"), a humorous motif suggesting the lasciviousness of the clergy that was common to a variety of genres in medieval literature.5 Landau, on the other hand, cites the miraculous tale "L'abbesse qui fu grosse" ("The Abbess Who Was Pregnant"), which vaguely resembles Boccaccio's story through its mention of hypocrisy among the clergy, but makes no use of the brache del prete topos.6 Since the topos is the same, Decameron IX.2 may be considered much more closely connected to one of the fabliaux than to the miraculous tale of the abbess.

Not included in the list enumerated by Branca is the thematically similar fabliau, Les Braies le priestre, which was also composed by Jean de Condé. Although this fabliau and the anonymous Les Braies au cordelier both make use of the theme of the brache del prete, they are not necessarily sources for Boccaccio's novella.7 This literary motif usually involves the theft or misplacement of a cleric's pants, with its implications of sexual relations. An example from the Legenda Aurea (number 146)—also cited by Branca—gives an anecdote from the life of St. Jerome whose clothes are stolen by his fellow monks and replaced by women's clothing. When he mistakenly dresses in these clothes, the other monks assume that he has been sleeping with a woman and that he erringly put on her clothing in the dark. There are, however, no breeches in this example of the topos. In Les Braies au cordelier, a man, having surprised his wife with a clerk, mistakes the clerk's pants for his own the next morning, and his delayed discovery of the mistake is the evidence of his wife's infidelity. Despite the similarities of dressing in the dark and mistaken clothing, these two examples in fact present two different types of stories: the former results in cross-dressing, while the latter involves a mere substitution of the cleric's pants for those of another man. The two distinct narratives which emerge from the theme of the brache del prete do not alter the implication of sexual (mis)behavior, but they do allow us to recognize that the anecdote about St. Jerome, which involves an example of cross-dressing, and Les Braies au cordelier, which consists of a substitution, belong to two discrete narrative traditions. Decameron IX.2 represents a combination of these two traditions, a mixture of cross-dressing and mistaken breeches. Of the possible sources for Decameron IX.2, only La Nonete demonstrates the same combination of the two traditions. Thus, La Nonete and Decameron IX.2 share more than similar plots and structures, but in fact share the same "textual nucleus."8 For this reason, La Nonete is the most probable source for Boccaccio's novella.

The basic plots of Decameron IX.2 and La Nonete show a remarkable number of similarities. In both stories, a young nun (or novice) is caught with a man. When the other nuns who caught her go to...

Jan-Maat wrote: "Hurrah! thanks to another short section I'm up to date again..."

Way to go Jan-Maat!!! While you're waiting for everyone to catch up, take this How Fast Do You Read test:

http://projects.wsj.com/speedread/

Way to go Jan-Maat!!! While you're waiting for everyone to catch up, take this How Fast Do You Read test:

http://projects.wsj.com/speedread/

Just started this section. In the intro, the description of the outing in the nearby woods with playful wild animals turned tame thanks to the interruption of hunting activity due to the pest, once again hinted at a state of innocence, either paradisiac or utopic...

Just started this section. In the intro, the description of the outing in the nearby woods with playful wild animals turned tame thanks to the interruption of hunting activity due to the pest, once again hinted at a state of innocence, either paradisiac or utopic...

Book Portrait wrote: "Just started this section. In the intro, the description of the outing in the nearby woods with playful wild animals turned tame thanks to the interruption of hunting activity due to the pest, once..."

Book Portrait wrote: "Just started this section. In the intro, the description of the outing in the nearby woods with playful wild animals turned tame thanks to the interruption of hunting activity due to the pest, once..."a nice point! Garden of Eden or Age of Gold?

Jan-Maat wrote: "a nice point! Garden of Eden or Age of Gold?"

Jan-Maat wrote: "a nice point! Garden of Eden or Age of Gold?"There's probably some courtly love setting references too? What's interesting is that the Pest is the catalyst for this extraordinary state, as if it had cleansed the world...

Book Portrait wrote: "Jan-Maat wrote: "a nice point! Garden of Eden or Age of Gold?"

Book Portrait wrote: "Jan-Maat wrote: "a nice point! Garden of Eden or Age of Gold?"There's probably some courtly love setting references too? What's interesting is that the Pest is the catalyst for this extraordinary..."

Hmmm...which makes me want to go back to the beginning, to see where he discusses the people who were dying, to see if there's any reference to the scourge of the Earth dying out, or whether it's Death as the great, non-discriminating equalizer...I think I remember (it's been so long, lol!) that some of the survivors, who worked carting off the dead, were less than savoury characters...

My recollection (it has been a while ^^) is that Boccaccio's description of Florence during the Pest was very realistic in the introduction. But once established that context has receded in the background to make way for a daily routine of pleasure and entertainment. Bearing in mind that Boccacio compiled and published his stories over many years iirc, I'm starting to wonder if there is an overarching theme or if he just decided to go for 100 stories because it's a round number. The stories felt a little more random and uneven in day 9 (of course there was no theme given by the day's queen) and it made me wonder if Boccaccio was scraping the bottom of the barrel or too busy to focus on these. I'm very curious to see how he'll end it all... which we'll soon find out! I also wonder if he was following a certain tradition (that of the fabliaux?) and to what extent his collection of stories is innovative (or if the innovation is all in the framing device)... Sorry I iz a little rambly atm. I think I should finally go read the introduction. ^.^

My recollection (it has been a while ^^) is that Boccaccio's description of Florence during the Pest was very realistic in the introduction. But once established that context has receded in the background to make way for a daily routine of pleasure and entertainment. Bearing in mind that Boccacio compiled and published his stories over many years iirc, I'm starting to wonder if there is an overarching theme or if he just decided to go for 100 stories because it's a round number. The stories felt a little more random and uneven in day 9 (of course there was no theme given by the day's queen) and it made me wonder if Boccaccio was scraping the bottom of the barrel or too busy to focus on these. I'm very curious to see how he'll end it all... which we'll soon find out! I also wonder if he was following a certain tradition (that of the fabliaux?) and to what extent his collection of stories is innovative (or if the innovation is all in the framing device)... Sorry I iz a little rambly atm. I think I should finally go read the introduction. ^.^

Yes, I've felt the same way with regard to the random nature of some of these--Day 6's stories were also pretty short, too (allowed me to catch up to y'all!:))

Yes, I've felt the same way with regard to the random nature of some of these--Day 6's stories were also pretty short, too (allowed me to catch up to y'all!:))But I like Jan-Maat's point about the Plague washing away some of the scourge of the Earth....just have to look back on it more closely (of course, since I'm mid-semester, new preps, and reading 9 things at once, there's a slim chance that this will actually happen!)