The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Hard Times

Hard Times

>

Part I Chapters 01 - 03

The second Chapter has the ominous title “Murdering the Innocents”, and it picks up the action where the preceding chapter left it. We are introduced by a rather sneering omniscient narrator to the schoolmaster Mr. Gradgrind, who is a man of facts, not only square in his views on life but also square of forefinger and square in the rest of his outward appearance – in a way the caricature of a utilitarian. He quizzes a new pupil, Sissy Jupe, the daughter of a carney, and finds her extremely deficient with regard to possessing the knowledge of facts. He even finds fault with her name, saying that Sissy is not a proper name and that she and her father ought to call her Cecilia instead. One of the other pupils, a boy named Bitzer, then gives the wished-for, encyclopedical definition of a horse.

The second Chapter has the ominous title “Murdering the Innocents”, and it picks up the action where the preceding chapter left it. We are introduced by a rather sneering omniscient narrator to the schoolmaster Mr. Gradgrind, who is a man of facts, not only square in his views on life but also square of forefinger and square in the rest of his outward appearance – in a way the caricature of a utilitarian. He quizzes a new pupil, Sissy Jupe, the daughter of a carney, and finds her extremely deficient with regard to possessing the knowledge of facts. He even finds fault with her name, saying that Sissy is not a proper name and that she and her father ought to call her Cecilia instead. One of the other pupils, a boy named Bitzer, then gives the wished-for, encyclopedical definition of a horse.His definition of a horse reminded me of Socrates and Plato’s well-structured way of defining all sorts of things, but also of Diogenes, who, on hearing that Plato rendered Socrates’s definition of man as “a featherless biped”, he brought a plucked chicken into the Academy and said, “Behold, I have brought you a man!”

Some consequences of Mr. Gradgrind’s education can already be seen in Bitzer, who is described as follows:

”His cold eyes would hardly have been eyes, but for the short ends of lashes which, by bringing them into immediate contrast with something paler than themselves, expressed their form. His short-cropped hair might have been a mere continuation of the sandy freckles on his forehead and face. His skin was so unwholesomely deficient in the natural tinge, that he looked as though, if he were cut, he would bleed white.”

It is probably also quite telling that the narrator makes a point of mentioning that the sunlight falling in through the windows first falls on Sissy Jupe and then, after passing a line of other pupils, comes last to Bitzer, who is apparently Mr. Gradgrind’s model student. At this point, the second adult, a government official, takes up the interrogation, trying to prove that it is not proper to decorate houses with wallpapers showing horses or carpets that have pictures of flowers on them as in real life horses are never seen to walk on walls and people never tread on flowers. Later, the new teacher is going to take over the class, and his name is, quite characteristically, Mr. M’Choakumchild. He is described as the typical specimen of a teacher at common schools at that time: Full of undigested factual knowledge and prone to stifling children’s imagination.

Chapter 3, „A Loophole“, sees Mr. Gradgrind on his way home. We learn that Mr. Gradgrind used to be in the wholesale hardware trade before he founded a school and that his ambition is to be a Member of Parliament one day. He lives in a house called Stone Lodge and looking like that:

Chapter 3, „A Loophole“, sees Mr. Gradgrind on his way home. We learn that Mr. Gradgrind used to be in the wholesale hardware trade before he founded a school and that his ambition is to be a Member of Parliament one day. He lives in a house called Stone Lodge and looking like that:”A very regular feature on the face of the country, Stone Lodge was. Not the least disguise toned down or shaded off that uncompromising fact in the landscape. A great square house, with a heavy portico darkening the principal windows, as its master’s heavy brows overshadowed his eyes. A calculated, cast up, balanced, and proved house. Six windows on this side of the door, six on that side; a total of twelve in this wing, a total of twelve in the other wing; four-and-twenty carried over to the back wings. A lawn and garden and an infant avenue, all ruled straight like a botanical account-book. Gas and ventilation, drainage and water-service, all of the primest quality. Iron clamps and girders, fire-proof from top to bottom; mechanical lifts for the housemaids, with all their brushes and brooms; everything that heart could desire.”

We further learn that Mr. Gradgrind has five children and that these children are brought up entirely on a diet of facts, facts, facts, and that fancy and imagination have no place in their everyday lives:

”There were five young Gradgrinds, and they were models every one. They had been lectured at, from their tenderest years; coursed, like little hares. Almost as soon as they could run alone, they had been made to run to the lecture-room. The first object with which they had an association, or of which they had a remembrance, was a large black board with a dry Ogre chalking ghastly white figures on it.

Not that they knew, by name or nature, anything about an Ogre Fact forbid! I only use the word to express a monster in a lecturing castle, with Heaven knows how many heads manipulated into one, taking childhood captive, and dragging it into gloomy statistical dens by the hair.

No little Gradgrind had ever seen a face in the moon; it was up in the moon before it could speak distinctly. No little Gradgrind had ever learnt the silly jingle, Twinkle, twinkle, little star; how I wonder what you are! No little Gradgrind had ever known wonder on the subject, each little Gradgrind having at five years old dissected the Great Bear like a Professor Owen, and driven Charles’s Wain like a locomotive engine-driver. No little Gradgrind had ever associated a cow in a field with that famous cow with the crumpled horn who tossed the dog who worried the cat who killed the rat who ate the malt, or with that yet more famous cow who swallowed Tom Thumb: it had never heard of those celebrities, and had only been introduced to a cow as a graminivorous ruminating quadruped with several stomachs.”

On his way home, Mr. Gradgrind passes the “Sleary’s Horse-riding” pavilion and is dismayed to find some of his pupils spying on the show from the back of the booth. Having a closer look at the culprits dismays him even more because he finds that two of his own children, his mathematical son Thomas and his metallurgical daughter Louise of fifteen or sixteen years, amongst them. He collars them and tells them off, whereupon Louisa confesses to having lured Thomas into coming with her. The children clearly show signs of their gloomy upbringing:

”There was an air of jaded sullenness in them both, and particularly in the girl: yet, struggling through the dissatisfaction of her face, there was a light with nothing to rest upon, a fire with nothing to burn, a starved imagination keeping life in itself somehow, which brightened its expression. Not with the brightness natural to cheerful youth, but with uncertain, eager, doubtful flashes, which had something painful in them, analogous to the changes on a blind face groping its way.”

His daughter tells him that she is tired – of everything, but he waves her words away and indignantly asks what Mr. Bounderby would say to all this. And here the chapter stops.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,I don’t know about you but for me time seemed to stand still or at least to move more slowly than usual without our weekly Dickens discussions. I must confess that I don’t have ..."

I agree with you regarding the beginnings of Dickens's novels. HT ranks as one of the best. It certainly sets a clear tone, and reduces all doubt as to what is important in this school.

Many people tend to forget the very clear attack on the Poor Law and theories of Malthus found within ACC as they were only a part of the greater power and richness of that novella.

In HT, there is no doubt from the start that Bentham's theories will be front and centre. "Now, what I want is, Facts. ... Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. ... Stick to the Facts, sir!"

Dickens's opinion is clear. The " plain , bare monotonous vault of a schoolroom," the repeated use of the words "wall" and "square" among others turns the schoolroom and the students into a prison with prisoners. What will be the consequence of such an environment?

Short, sweet and to the point. HT will be a short novel, a novel without illustrations, but it will be a novel of immense power. Immediately after its serial publication Dickens published, again in parts, Elizabeth Gaskell's North and South. Within a very short time frame, arguably the two greatest industrial novels of the 19C were published.

Tristram wrote: "The second Chapter has the ominous title “Murdering the Innocents”, and it picks up the action where the preceding chapter left it. We are introduced by a rather sneering omniscient narrator to the..."

Tristram wrote: "The second Chapter has the ominous title “Murdering the Innocents”, and it picks up the action where the preceding chapter left it. We are introduced by a rather sneering omniscient narrator to the..."What a delightful ( or would that be horrid?) name for a teacher. M'Choakumchild. Such a subtle and yet perfectly cast name. Let there be no imagination. Banish all fancy. Render children to the glad grinding (Gradgrind) of a system created to create the maximum benefit for the majority of the people.

Gradgrind, as Tristram noted, is a man of squares and edges. He is a man of measurement rather than a man of roundness and variety. There is great irony in the fact that a young girl who is totally familiar with the essence of a horse cannot define a horse while a boy who no doubt has never spent any time with a horse is seen to know, by definition, what a horse is really like.

More names to reflect upon are presented in this chapter. Sissy Jupe must be Cecilia. According to the school system she must never fancy. She must be, in all things, regulated and governed. Saint Cecelia is the patron saint of music. In this early chapter, Dickens is setting up the conflict between rules and creativity, between what can be defined and what cannot.

Gradgrind == Grade Grind? Such schooling is a grind?

Gradgrind == Grade Grind? Such schooling is a grind?Note how his physical description, dress, and attitude matches his all facts approach to everything == "square forefinger," "square wall of a forehead," "inflexible, dry, and dictatorial," "mouth ... wide, thin, and hard set," and "square coat, square legs, square shoulders."

Mr. Gradgrind is a man of sharp and no nonsense lines and edges. He is an interesting and unnatural creation. Nature has no such lines and edges.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 3, „A Loophole“, sees Mr. Gradgrind on his way home. We learn that Mr. Gradgrind used to be in the wholesale hardware trade before he founded a school and that his ambition is to be a Membe..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 3, „A Loophole“, sees Mr. Gradgrind on his way home. We learn that Mr. Gradgrind used to be in the wholesale hardware trade before he founded a school and that his ambition is to be a Membe..."Gradgrind's house is like Gradgrind, or is it the other way round? Either way, we read of a world devoid of individualism and stuffed full of efficiency and order. How delightful that two of Gradgrind's children are peeking at the world of the circus, a place of imagination and fancy. How predictable is Gradgrind's reaction. For his children " There was an air of jade sullenness in them both ... there was a light with nothing to rest upon, a fire with nothing to burn, a starved imagination keeping life in itself somehow ..."

At the end of the first week's reading Dickens's first audience must have wondered what would happen to all the children introduced so far in the novel. And so do we.

The teacher says to his students:

The teacher says to his students:"[Y]ou are not to see anywhere, what you don't see in fact; you are not to have anywhere, what you don't have in fact."

I am reminded of the lyrics in Pink Floyd's Another Brick in the Wall. It sounds Dickens. Is it a play on Dickens?

We don't need no education

We don't need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers leave them kids alone

Hey! teachers! leave the kids alone!

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

We don't need no education

We don't need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers leave them kids alone

Hey! teacher! leave us kids alone!

All in all you're just a another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just a another brick in the wall.

-smooth guitar solo-

"Wrong, do it again!"

"Wrong, do it again!"

"If you don't eat yer meat, you can't have any pudding. how can you

Have any pudding if you don't eat yer meat?"

"you! yes, you behind the bikesheds, stand still laddy!"

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "The teacher says to his students:

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "The teacher says to his students:"[Y]ou are not to see anywhere, what you don't see in fact; you are not to have anywhere, what you don't have in fact."

I am reminded of the lyrics in Pink Floyd..."

Pink Floyd and Dickens. Love it!

Bricks actually came to my mind when I was reading of Gradgrind and his school, Xan. It's also quite telling that the narrator likens the pupils to vessels that are to be filled with knowledge and facts, thus showing that Gradgrind education is a thing to be received passively, whereas nowadays we tend to think that you have to be active to construct your own body of knowledge, and not just cram dead facts that are paraded before you, i.e. put your nose to the gradgrindstone.

Bricks actually came to my mind when I was reading of Gradgrind and his school, Xan. It's also quite telling that the narrator likens the pupils to vessels that are to be filled with knowledge and facts, thus showing that Gradgrind education is a thing to be received passively, whereas nowadays we tend to think that you have to be active to construct your own body of knowledge, and not just cram dead facts that are paraded before you, i.e. put your nose to the gradgrindstone.I did not know about St. Cecilia, Peter - so thank you for pointing that out. About utilitarianism, I am always in two minds: On the one hand, I think that Bentham espcially was quite naive and that the highest degree of good for the largest number of people would imply that minorities' rights might be infringed too easily, but on the other hand I think that a code of ethics should be based on rational considerations and that ethics should serve people and not the other way round. Kant's deontology, if carried to extremes, would surely lead to absurd decisions in some cases; I'm thinking of his own example of a person hiding in a house and his would-be murderer asking you if that person has hid in the house, and you being supposed to answer truthfully because one of the morals laws compels you to being truthful. It's Kant's objection to making any exceptions to ehtical rules that leaves me clueless.

Thinking of Gaskell's North and South, that might be a candidate for further group readings in our Club once we have done with the Dickens novels.

Thinking of Gaskell's North and South, that might be a candidate for further group readings in our Club once we have done with the Dickens novels.

Tristram touched on all the things that jumped out at me as I read our first installment: the name M’Choakumchild; the description of Gradgrind's house (love the bit where Dickens likens the portico to Gradgrind's brow); and the square forefinger. The latter probably would have slipped right past had we not just finished Bleak House but, of course, after our discussions of Allegory and Bucket and their prominent pointers, this passage had new importance.

Tristram touched on all the things that jumped out at me as I read our first installment: the name M’Choakumchild; the description of Gradgrind's house (love the bit where Dickens likens the portico to Gradgrind's brow); and the square forefinger. The latter probably would have slipped right past had we not just finished Bleak House but, of course, after our discussions of Allegory and Bucket and their prominent pointers, this passage had new importance. I am immediately enjoying HT because Dickens jumps right into the characters - my favorite part of his writing - rather than give us a long, descriptive passage of the setting. No grime, no fog, no "gathering gloom", yet he still successfully sets the mood in his description of the people. We can all identify with Sissy, who freezes up when the teacher calls on her, and we immediately want to follow her story and find out what effect this unimaginative educational method is going to have on these children.

I haven't read any Gaskell, but have watched the videos of "Wives and Daughters", "North and South", and "Cranford". She's definitely on my to-read list, and I'd love to do that with this group.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram touched on all the things that jumped out at me as I read our first installment: the name M’Choakumchild; the description of Gradgrind's house (love the bit where Dickens likens the portic..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram touched on all the things that jumped out at me as I read our first installment: the name M’Choakumchild; the description of Gradgrind's house (love the bit where Dickens likens the portic..."Yes. There is a more direct and urgent feel to this novel than Dickens's previous ones. The weekly publication format of HT will give us a leaner style with fewer characters and no illustrations.

I wonder how Dickens original readership reacted to the about face in style and format in HT. I will miss the long, drawn out descriptions of place and person but it will be exciting to see Dickens adapting to the weekly format. He too must have felt a major shift in his routine and his writing habits.

Tristram wrote: "Thinking of Gaskell's North and South, that might be a candidate for further group readings in our Club once we have done with the Dickens novels."

Tristram wrote: "Thinking of Gaskell's North and South, that might be a candidate for further group readings in our Club once we have done with the Dickens novels."Tristram

How sad to think that we will ever be done with Dickens. Once in awhile this fact does pop its head up and peer at us.

I figure we are safe until at least 2018. Then we should hold a massive Pickwickian convention where we all get together to figure out what to do next. Naturally, we could hold the convention somewhere in England. Failing that, what better place than Victoria, British Columbia? :-))

Peter wrote:"How sad to think that we will ever be done with Dickens. Once in awhile this fact does pop its head up and peer at us.

Peter wrote:"How sad to think that we will ever be done with Dickens. Once in awhile this fact does pop its head up and peer at us.I figure we are safe until at least 2018."

I'm sure I can speak for all of us who were late to the party -- can't we just start over again?? You can never read Dickens too many times. :-)

When I noticed that Gradgrind's house was called Stone Lodge, the idiom "keep your nose to the grindstone", came straight to mind. I'm not sure if it's just an English saying, however, it means working consistently hard. It also made me imagine how he managed to get everything, including his own physical features, so straight and square. Ha ha.

When I noticed that Gradgrind's house was called Stone Lodge, the idiom "keep your nose to the grindstone", came straight to mind. I'm not sure if it's just an English saying, however, it means working consistently hard. It also made me imagine how he managed to get everything, including his own physical features, so straight and square. Ha ha.

I agree with comments already made, regarding the omniscient narrator, who I feel is satirising Gradgrind and the school system, or rather, should I say Dickens is, especially in regards to the lack of imagination of the students in this institution.

I agree with comments already made, regarding the omniscient narrator, who I feel is satirising Gradgrind and the school system, or rather, should I say Dickens is, especially in regards to the lack of imagination of the students in this institution.I hope Louisa is going to be the spanner in Gradgrind's well oiled works!

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote:"How sad to think that we will ever be done with Dickens. Once in awhile this fact does pop its head up and peer at us.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote:"How sad to think that we will ever be done with Dickens. Once in awhile this fact does pop its head up and peer at us.I figure we are safe until at least 2018."

I'm sure I can speak ..."

I would be thrilled to simply start again.

Also, I'm interested to know if anyone has picked up the change in syntax, to represent the dialect in Dickens' northern town? It's easy for me to pick up, being from the north of England, however, I'm interested if anyone has spotted it.

Also, I'm interested to know if anyone has picked up the change in syntax, to represent the dialect in Dickens' northern town? It's easy for me to pick up, being from the north of England, however, I'm interested if anyone has spotted it.

Kate wrote: "When I noticed that Gradgrind's house was called Stone Lodge, the idiom "keep your nose to the grindstone", came straight to mind. I'm not sure if it's just an English saying, however, it means wor..."

Kate wrote: "When I noticed that Gradgrind's house was called Stone Lodge, the idiom "keep your nose to the grindstone", came straight to mind. I'm not sure if it's just an English saying, however, it means wor..."Hi Kate

You are right. Dickens's homes tend to reflect their owners' personalities. It will be interesting to follow the various homes in HT.

By the way, can you invision the school's appearance?

I'm finding the change of style in this novel difficult, I'm afraid. Ironically, I felt I was back in school, reading an essay. In which I'm hit over the head by the point. (Is that the point?) Despite the sparseness, it felt heavy-handed, particularly repeating the word 'emphasis' in the first chapter (page). Emphasizing emphasis. Overkill. I'm missing Bleak House!

I'm finding the change of style in this novel difficult, I'm afraid. Ironically, I felt I was back in school, reading an essay. In which I'm hit over the head by the point. (Is that the point?) Despite the sparseness, it felt heavy-handed, particularly repeating the word 'emphasis' in the first chapter (page). Emphasizing emphasis. Overkill. I'm missing Bleak House!On the other hand, I enjoyed Gradgrind's introduction of himself in Chap 2 with a list of 'suppositions, non-existent persons' -- bordering dangerously close to using his imagination :) I also loved the slow corpulent boy telling the government official he wouldn't paper a wall, but paint it -- questioning the question itself.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "The teacher says to his students:

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "The teacher says to his students:"[Y]ou are not to see anywhere, what you don't see in fact; you are not to have anywhere, what you don't have in fact."

I am reminded of the lyrics in Pink Floyd..."

I was reminded strongly of Orwell by the government administrator, particularly the goal of having "a board of fact, composed of commissioners of fact, who will force the people to be a people of fact..." His thought police idea is similar to Pink Floyd's thought control, come to think of it. Thanks, Xan.

I found the official's equation of Taste with Fact, very disturbing. I took a quick look, and apparently Dickens was among the writers who influenced Orwell. Now I can see why.

Mary Lou wrote: "I haven't read any Gaskell, but have watched the videos of "Wives and Daughters", "North and South", and "Cranford". She's definitely on my to-read list..."

Mary Lou wrote: "I haven't read any Gaskell, but have watched the videos of "Wives and Daughters", "North and South", and "Cranford". She's definitely on my to-read list..."She's on my list, too. I just started Cranford, and am looking forward to North & South. I hope Dickens gives us more description of an industrial town here...

As to our list of books to be read, I have not calculated how far the remaining books - if I remember correctly, we agreed to read Pickwick Papers again after The Mystery of Edwin Drood because most of us were not here when PP was being read the first time - will take us.

As to our list of books to be read, I have not calculated how far the remaining books - if I remember correctly, we agreed to read Pickwick Papers again after The Mystery of Edwin Drood because most of us were not here when PP was being read the first time - will take us.Then I don't know whether you would like to read texts like Pictures from Italy, A Child's History of England, The Life of Our Lord or collaborations Dickens had with other authors, such as A House to Let, A Haunted House, A Message from the Sea. Then Dickens also wrote some plays. Some of these texts are hard to get and that was one of the reasons why I bought an e-reader last year: The Complete Delphi Edition of Charles Dickens also comprises these texts but frankly speaking, I am quite daunted by titles like Pictures of Italy (I don't normally enjoy people's travel accounts) or A Child's History of England (I prefer history for adults), and so we might make a selection of what we might want to read when the moment has arrived ... in 2017 or 2018, that is. All I know is that reading classics in a group is more fun than doing in on one's own.

Kate wrote: "Also, I'm interested to know if anyone has picked up the change in syntax, to represent the dialect in Dickens' northern town? It's easy for me to pick up, being from the north of England, however,..."

Kate wrote: "Also, I'm interested to know if anyone has picked up the change in syntax, to represent the dialect in Dickens' northern town? It's easy for me to pick up, being from the north of England, however,..."As yet, I have not spotted it but I will pay more attention to the syntax used by Gradgrind et alii in the next few chapters.

Vanessa wrote: "I'm finding the change of style in this novel difficult, I'm afraid. Ironically, I felt I was back in school, reading an essay. In which I'm hit over the head by the point. (Is that the point?) Des..."

Vanessa wrote: "I'm finding the change of style in this novel difficult, I'm afraid. Ironically, I felt I was back in school, reading an essay. In which I'm hit over the head by the point. (Is that the point?) Des..."Vanessa wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "The teacher says to his students:

"[Y]ou are not to see anywhere, what you don't see in fact; you are not to have anywhere, what you don't have in fact."

I am reminded o..."

I agree with you, Vanessa: I also found the public official's excursion on wallpapers and carpets quite over the top and devoid of the subtlety of Bleak House or David Copperfield. Still, the reactions of the pupils were funny, as has already been pointed out here, and what I liked best about them was how the narrator underlined that the pupils, in their answers, took into consideration what they thought was expected of them to say. It's like in real school life, when, for instance, the teacher does not directly want to correct a student's answer and so he asks the class if they all agree. Even the most naive of students would certainly not agree after such a question.

I can't bring myself to completely dislike Mr. Gradgrind, though, because I think he is really acting from conviction of helping these children to get on in life. He may have his parliamentary ambitions but he believes in Facts, for sure. Thus, he is more like Dr. Blimber, who also believed in cramming, but who was not evil-hearted, and less like Mr. Squeers, who was just a cruel impostor. So Mr. Gradgrind promises to be a more serious character after all.

Tristram wrote: "As to our list of books to be read, I have not calculated how far the remaining books - if I remember correctly, we agreed to read Pickwick Papers again after The Mystery of Edwin Drood because mos..."

Tristram wrote: "As to our list of books to be read, I have not calculated how far the remaining books - if I remember correctly, we agreed to read Pickwick Papers again after The Mystery of Edwin Drood because mos..."Oh, Goody, we will reread Pickwick Papers!!! Haven't read that one.

I have the Delphi Edition too. Love it. Only drawback is there is no chapter list in TC, only books, etc list. At least in my copy.

Vanessa wrote: the goal of having a board of fact, composed of commissioners of fact, who will force the people to be a people of fact......"

Vanessa wrote: the goal of having a board of fact, composed of commissioners of fact, who will force the people to be a people of fact......"As has been pointed out by others, there is little subtlety in these opening chapters. I thought the Board of Fact was hilarious and telling. Hilarious because the notion of running society solely on facts is preposterous to the point of laughter. Telling because Gradgrind, the teacher, and the official are so caught up and lost in the excitement of a new idea and high purpose they cannot see this. They are like the grand philanthropists of BH, so caught up in their own greatness and purpose they cannot see the destruction they wreak around them. Unintended consequences -- a world based solely on reason is a world devoid of creative imagining — no more poets, no more comedians, no more fiction writers, no more human spirit.”

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: " a world based solely on reason is a world devoid of creative imagining — no more poets, no more comedians, no more fiction writers, no more human spirit.”

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: " a world based solely on reason is a world devoid of creative imagining — no more poets, no more comedians, no more fiction writers, no more human spirit.”Not to mention the fact (pun not intended, but amusing, nonetheless) that facts change. Look at dietary guidelines over the past 30 years or so. Every few years some study will come out resulting in the belief that eggs, for example, are bad for you. Then another study comes out that they're good for you. Same with coffee, wine, carbs, red meat, etc. etc. etc. It was once considered fact that the world was flat. Without theory, supposition, and imagination we learn nothing new.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Gradgrind == Grade Grind? Such schooling is a grind?."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Gradgrind == Grade Grind? Such schooling is a grind?."It has that very Germanic feel of two words smashed together to make a new one.

Tristram wrote: "...thus showing that Gradgrind education is a thing to be received passively, whereas nowadays we tend to think that you have to be active to construct your own body of knowledge, and not just cram dead facts that are paraded before you ..."

Tristram wrote: "...thus showing that Gradgrind education is a thing to be received passively, whereas nowadays we tend to think that you have to be active to construct your own body of knowledge, and not just cram dead facts that are paraded before you ..."And yet, education today, in this country at least, isn't all that far in principle from Gradgrind's principles. All this testing, testing, testing, is mostly testing for facts. Teachers are expected to cram into their students the facts they will need to pass these standardized tests.

Standardized tests, standardized students.

All around this country, at least, the non-facts aspects of education -- art, music, etc. -- are being shunted aside in favor of more facts that the students can regurgitate onto the standardized tests.

Kate wrote: "I hope Louisa is going to be the spanner in Gradgrind's well oiled works! "

Kate wrote: "I hope Louisa is going to be the spanner in Gradgrind's well oiled works! "I immediately thought of Louisa (aka Louie) from The Man Who Loved Children, who is struggling to escape her father's influence.

(New Pickwickian with bad etiquette here.....I'm off to the Lounge to say hello right now.)

HT was written in the early 1860s, when Romanticism was dying out. Was Dickens reflecting on this change in society?

HT was written in the early 1860s, when Romanticism was dying out. Was Dickens reflecting on this change in society?

What with Hard Times and Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens certainly didn't give us a very pleasant picture of education in Victorian England.

What with Hard Times and Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens certainly didn't give us a very pleasant picture of education in Victorian England.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "a world based solely on reason is a world devoid of creative imagining — no more poets, no more comedians, no more fiction writers, no more human spirit.” "

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "a world based solely on reason is a world devoid of creative imagining — no more poets, no more comedians, no more fiction writers, no more human spirit.” "Which would be exactly like the ideal society Plato described in Politea, a book that always makes me shudder.

Everyman wrote: "It has that very Germanic feel of two words smashed together to make a new one. ."

Everyman wrote: "It has that very Germanic feel of two words smashed together to make a new one. ."Just two words smashed together? Amateurs ;-)

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "...thus showing that Gradgrind education is a thing to be received passively, whereas nowadays we tend to think that you have to be active to construct your own body of knowledge, ..."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "...thus showing that Gradgrind education is a thing to be received passively, whereas nowadays we tend to think that you have to be active to construct your own body of knowledge, ..."In Germany, teaching competences is the latest fashion, and traditional teachers complain that students know less and less and are not even any more expected to know things. Competences in English as a foreign language are, for instance, divided in Intercultural Competences - i.e. the knowledge of certain cultural differences and the skill to navigate aptly in a given culture (e.g. not expecting everyone to shake hands with you whenever you meet them, or not going straight to a table in a restaurant without waiting to be led to one) as well as the ability to compare and combine different sorts of value systems -, Communicative Competences - e.g. reading comprehension, listening comprehension etc. -, methodical competences, e.g. analyzing texts and Cooperative Competences. There's a whole catalogue of Competences, and each lesson should consider at least one or two of them.

Whereas I can understand to a certain degree that competences are important in a society in which knowledge becomes obsolete very quickly due to new research, I think that the idea of teaching competences also includes the danger of utilitarianism in education. What about reading texts for pleasure, for instance? Does school not also have the task to give students a chance to experience and discuss the beauties of Shakespeare's language? Why use Shakespeare's text exclusively as a quarry of materials with which to exercise competences? It has a barbaric ring to it.

And then, paradoxically - because there is always a model solution expected - students are becoming less and less self-dependent and instead want to know more and more what they are supposed to answer.

The Gradgrind way is not the only one to make young people stop thinking for themselves.

Another example of standardization: Assignments are supposed to contain certain verbs, in German they are called "Operatoren", which tell students what they have to do. For example, if you want them to see the two sides of a problem, you have to use the word "Discuss (the problem)", and if you want them to give their own opinion, you have to write "Comment on (the problem)".

Another example of standardization: Assignments are supposed to contain certain verbs, in German they are called "Operatoren", which tell students what they have to do. For example, if you want them to see the two sides of a problem, you have to use the word "Discuss (the problem)", and if you want them to give their own opinion, you have to write "Comment on (the problem)".Now, for years, when you wanted them to write a characterization of, let's say, Mr. Gradgrind, you had to use the verb "Characterize" - thus it would be something like "Characterize Mr. Gradgrind and his behaviour as presented in the given extract."

I always wrote "Write a characterization" because to me, the word "characterize" in that context seems odd. I would rather use it in the passive, e.g. "Mr. Gradgrind is characterized by his unshaken belief in Fact." Most of my colleagues used the word "characterize" anyway because they thought it was more important to stick to the rules than to avoid using awkward English. Now, however, the Operator was changed from "characterize" to "write a characterization". Maybe, finally, someone, a native English speaker, looked over the Operatoren?

From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:"I wish you would look" (20th of January 1854) "at the enclosed titles for the H. W. story, between this and two o'clock or so, when I will call. It is my usual day, you observe, on which I have jotted them down—Friday! It seems to me that there are three very good ones among them. I should like to know whether you hit upon the same." On the paper enclosed was written: 1. According to Cocker. 2. Prove it. 3. Stubborn Things. 4. Mr. Gradgrind's Facts. 5. The Grindstone. 6. Hard Times. 7. Two and Two are Four. 8. Something Tangible. 9. Our Hard-headed Friend. 10. Rust and Dust. 11. Simple Arithmetic. 12. A Matter of Calculation. 13. A Mere Question of Figures. 14. The Gradgrind Philosophy.[180] The three selected by me were 2, 6, and 11; the three that were his own favourites were 6, 13, and 14; and as 6 had been chosen by both, that title was taken."

"It was the first story written by him for Household Words; and in the course of it the old troubles of the Clock came back, with the difference that the greater brevity of the weekly portions made it easier to write them up to time, but much more difficult to get sufficient interest into each. "The difficulty of the space," he wrote after a few weeks' trial, "is crushing. Nobody can have an idea of it who has not had an experience of patient fiction-writing with some elbow-room always, and open places in perspective. In this form, with any kind of regard to the current number, there is absolutely no such thing." He went on, however; and, of the two designs he started with, accomplished one very perfectly and the other at least partially. He more than doubled the circulation of his journal; and he wrote a story which, though not among his best, contains things as characteristic as any he has written."

Kim wrote: "From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

Kim wrote: "From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:"I wish you would look" (20th of January 1854) "at the enclosed titles for the H. W. story, between this and two o'clock or so, when I will call..."

Thanks for this Kim. It is not difficult to imagine Dickens feeling very constrained with the writing of HT after his great flight with BH. Obviously, however, it is obvious that his original readers were eager for the brevity of HT.

It is also interesting to note how aware of his reading audience Dickens was. He kept a close eye on circulation numbers. As we know he also fine tuned his characters at times to respond to his readers' tastes.

When we get to Great Expectations we will see how Dickens had refined and improved upon the rhythms and demands of the weekly serial.

I miss the illustrations and try to imagine what the characters and settings would have looked like in my mind's eye.

Peter wrote: "I miss the illustrations and try to imagine what the characters and settings would have looked like in my mind's eye. ."

Peter wrote: "I miss the illustrations and try to imagine what the characters and settings would have looked like in my mind's eye. ."We apparently don't have original illustrations (perhaps because this was a weekly serial which didn't give adequate time to make the drawings, get approval, and carve the plates?). But for our other reads so far we (mostly Kim) have found a variety of illustrations by other artists. I wonder whether there are a variety of secondary illustrators of Hard Times, too.

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "I miss the illustrations and try to imagine what the characters and settings would have looked like in my mind's eye. ."

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "I miss the illustrations and try to imagine what the characters and settings would have looked like in my mind's eye. ."We apparently don't have original illustrations (perhaps beca..."

Yes. The original weekly instalments did not include illustrations due to the time constraints of making the plate.

The original parts of GE were also published in weekly parts and do not contain illustrations. Other later versions of the novels would contain illustrations, but as a purist if the plate were not by H.K. Browne (Cruickshank no longer illustrated for Dickens) it's just not the same.

I just read this first section last night, and for a short section there are a lot of comments! I will take time a little later to read through them, but I just wanted to say that I almost choked with surprise when I read the name of "Mr. McChoakumchild"! This group has always had a fun time discussing the names of Dickens' characters, but this one really takes the cake. I don't think we have to imagine much to figure out what Dickens was going with this one!

I just read this first section last night, and for a short section there are a lot of comments! I will take time a little later to read through them, but I just wanted to say that I almost choked with surprise when I read the name of "Mr. McChoakumchild"! This group has always had a fun time discussing the names of Dickens' characters, but this one really takes the cake. I don't think we have to imagine much to figure out what Dickens was going with this one!Also, it was really nice to get back to reading a Dickens book, it felt so comfortable and almost like "going home" in a way. I've missed having a Dickens in my book pile since I took a break while you guys were all reading Bleak House. It's good to be back! :)

Ok all, here we go:

Ok all, here we go:The only artist to work on plates for the novel during Dickens's lifetime was the celebrated painter and magazine-illustrator Fred Walker, who began his career as an illustrator at Once a Week alongside the legendary George Du Maurier in 1860. For the 1868 Library Edition of Dickens works he contributed four illustrations to accompany Hard Times-- all signed with the initials "F. W. None of them are from this section though, so I guess I'll wait until we get there.

The next significant artist to illustrate the short novel was Harry French, who provided a comprehensive program of a frontispiece and nineteen full-size plates for the Household Edition published by Chapman and Hall in the 1870s. Here is the title page:

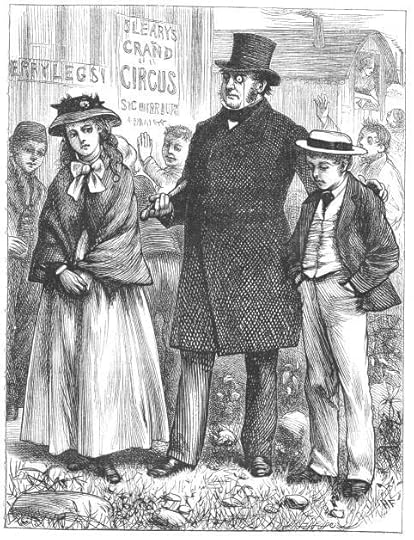

Thomas Gradgrind Apprehends His Children Louisa and Tom at the Circus

Book One, Chapter Three

Henry French

"American-born but European-trained artist C. S. [Charles Stanley] Reinhart's sixteen plates for Charles Dickens's Hard Times. For These Times appeared in the single-volume, American version of the Household Edition published in 1876 by Harper & Brothers." Here is the first:

"American-born but European-trained artist C. S. [Charles Stanley] Reinhart's sixteen plates for Charles Dickens's Hard Times. For These Times appeared in the single-volume, American version of the Household Edition published in 1876 by Harper & Brothers." Here is the first:

Book One, Chapter Three

C. S. Reinhart

Text Illustrated:

"Thomas Gradgrind took no heed of these trivialities of course, but passed on as a practical man ought to pass on, either brushing the noisy insects from his thoughts, or consigning them to the House of Correction. But, the turning of the road took him by the back of the booth, and at the back of the booth a number of children were congregated in a number of stealthy attitudes, striving to peep in at the hidden glories of the place.

This brought him to a stop. "Now, to think of these vagabonds," said he, "attracting the young rabble from a model school."

A space of stunted grass and dry rubbish being between him and the young rabble, he took his eyeglass out of his waistcoat to look for any child he knew by name, and might order off. Phenomenon almost incredible though distinctly seen, what did he then behold but his own metallurgical Louisa, peeping with all her might through a hole in a deal board, and his own mathematical Thomas abasing himself on the ground to catch but a hoof of the graceful equestrian Tyrolean flower-act!

Dumb with amazement, Mr. Gradgrind crossed to the spot where his family was thus disgraced, laid his hand upon each erring child, and said:

"Louisa!! Thomas!!"

Both rose, red and disconcerted. But, Louisa looked at her father with more boldness than Thomas did. Indeed, Thomas did not look at him, but gave himself up to be taken home like a machine. [Book One, Chapter Three, "A Loop-hole,"

Commentary:

Commentary

"Although the publisher, Harper and Brothers, has placed the second illustration immediately above the opening of the book, the moment illustrated comes in the third chapter, "A Loop-hole," when Thomas Gradgrind on his way home from his model school catches his two eldest children, Tom and Louisa, peeping "through a hole in a deal board" to watch the Tyrolean flower-act of the horse-riders. He has taken his eyeglass out of his waistcoat pocket to examine a number of children at the back of the booth, but Reinhart indicates just the two; as in the plate, in the text Louisa is standing and Tom is on the ground. In the background, Reinhart shows several circus wagons on the stubbly grass of "the neutral ground upon the outskirts of the town," and, on the horizon, the smoke-stacks of Coketown's satanic mills. Since, however, Gradgrind crosses the intervening ground to confront the malefactors in the text, one presumes he has already put his eyeglass back in his waistcoat pocket by the time we reach the moment Reinhart has chosen to depict. Furthermore, Louisa in Reinhart's picture seems a little younger than the pretty fifteen- or sixteen-year-old of the text — a not particularly fetching, in contrast to the Louisa whom Harry French has given the British reading public in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition.

While Tom and Louisa have both the natural curiosity and flexibility of youth, their father in his correct frockcoat, leather gloves, and top-hat (possibly a beaver) seems a wooden, black column — shades of Charlotte Brontë's description of the Reverend Mr. Brocklehurst as "a black pillar" in the Gateshead and Lowood sections of Jane Eyre (1847).

We are about to encounter a scene of submission and indoctrination in Coketown's schoolhouse in Chapter 2, "Murdering the Innocents." However, here the brother and sister, Tom and Louisa Gradgrind, the novel's central figures, are defying the Utilitarian precepts of their mentally inflexible parent. And yet, the philanthropist funding the other educational venture (if one accepts Dickens's notion that the circus, too, is intellectually as well as emotionally "improving"), the retired industrialist Thomas Gradgrind, is not the vicious disciplinarian that the Reverend Mr. Brocklehurst is at Lowood School. Thomas Gradgrind is well-meaning, but misguided — and Therefore faintly ridiculous.

However, as ensuing scenes make clear, Gradgrind like the black pillar master of Lowood suffers from a lack of human sympathy at the outset of the story, undervaluing emotion and "fancy." In Reinhart's plate for the third chapter, Gradgrind's eyeglass suggests that he cannot see what is immediately before him (his children peeping through a hole in the circus tent), and his cane may be poised to offer chastisement. Reinhart's Sixties' style style is in marked contrast to the careful detail (i. e., convincing the viewer of the verisimilitude of the illustration by painstaking details in the setting and costumes, in particular) of the previous generation of illustrators such as Phiz and Cruikshank, as his poster of the horse-riding acrobat (upper left) indicates.

line drawing of a prancing horse serves as an interesting headnote for the early chapters since in the second chapter Sissy Jupe fails to "define" a horse according to Gradgrind's formula, as exemplified by Bitzer's rote-memory definition. Reinhart accentuates the figures with fine cross-hatching, and gives an impression of such elements of setting as the tent, the grass, the waggons of Slearly's company indicative of the itinerant life-style, and the polluting smoke from the Coketown mills in the distance that spreads out across the cloudy skies above. In this modern perspective of the city, what dominates the distant skyline is not the belfries, steeples, and towers of places of worship, but the smoke-stacks and chimneys of Mammon, sponsoring deity of commerce and industry."

I don’t know about you but for me time seemed to stand still or at least to move more slowly than usual without our weekly Dickens discussions. I must confess that I don’t have too great expectations in Hard Times – but then I did not have particularly hard times reading Great Expectations – because it is such a short book, and I really like Dickens’s characters accompanying me for a longer time. On the other hand, reading the first part as it was read by contemporary readers makes up for that shortness to some degree.

The first Chapter, however, which is called “The One Thing Needful”, is extremely short, so short even that I cannot by any means quote from it but could instead copy the whole chapter. Which I won’t do. It introduces us into the scene of a schoolroom without giving any names. Instead, all we learn is that there are three adult people in it and a lot of pupils – and one of the adults is giving a short lecture on the importance of teaching facts – and facts only – to young children. By the way, the beginning of the chapter with its repetition of the word “facts” is, to me, one of the beginnings of Dickens’s books I remember best – along with the beginnings of David Copperfield, Bleak House, Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities.

It might also be added here that the three Parts of Hard Times bear the titles “Sowing”, “Reaping” and “Garnering”, which, at first sight, is quite odd since these terms clearly refer to agriculture whereas the novel is set in an industrial town and deals with trade unionism and the plights of workers. However, when one looks at the first words of Mr. Gradgrind, i.e. at his encomium on facts, one will find that he uses metaphors of “planting” facts and “rooting out” everything else and that he says that not only does he use this principle when teaching his pupils but that he also brings up his own children this way. Maybe the novel will give us some insight into what Mr. Gradgrind will harvest in the end?