The Pickwick Club discussion

Hard Times

>

Part I, Chapters 11-12

Chapter 12 is titled "An Old Woman" and at the beginning of the chapter Stephen has just left the home of Bounderby when he is stopped by the old woman of the title. She tells him she has traveled into the city from the country. She says that every year she saves enough money to make the long journey into Coketown for a single day, just long enough to catch a glimpse of Mr. Bounderby.

Chapter 12 is titled "An Old Woman" and at the beginning of the chapter Stephen has just left the home of Bounderby when he is stopped by the old woman of the title. She tells him she has traveled into the city from the country. She says that every year she saves enough money to make the long journey into Coketown for a single day, just long enough to catch a glimpse of Mr. Bounderby.‘No, no. Once a year,’ she answered, shaking her head. ‘I spend my savings so, once every year. I come regular, to tramp about the streets, and see the gentlemen.’

‘Only to see ’em?’ returned Stephen.

‘That’s enough for me,’ she replied, with great earnestness and interest of manner. ‘I ask no more! I have been standing about, on this side of the way, to see that gentleman,’ turning her head back towards Mr. Bounderby’s again, ‘come out. But, he’s late this year, and I have not seen him. You came out instead. Now, if I am obliged to go back without a glimpse of him—I only want a glimpse—well! I have seen you, and you have seen him, and I must make that do.’ Saying this, she looked at Stephen as if to fix his features in her mind, and her eye was not so bright as it had been.

With a large allowance for difference of tastes, and with all submission to the patricians of Coketown, this seemed so extraordinary a source of interest to take so much trouble about, that it perplexed him. But they were passing the church now, and as his eye caught the clock, he quickened his pace."

The old woman follows him to Bounderby’s grim factory and inexplicably praises its beauty, she takes it for granted that he must be happy working for such a man. I suppose we could consider this chapter the "mystery" chapter, since not only is it a mystery as to who this old woman is, but it is more of a mystery why anyone would worship Bounderby the way she does. At first my guess was she was perhaps his abandoned wife we haven't heard of yet, but why would a wife he abandoned travel anywhere for a glimpse of him, and she seems too old for him anyway. So now I'm leaning toward his mother, although I remember his story of being raised by his grandmother, I can't remember what happened to his mother. Perhaps it is the grandmother, egg box and all, in to Coketown from her country ditch for the day. There is even this as Stephen finally parts from the old woman:

‘I must kiss the hand,’ said she, ‘that has worked in this fine factory for a dozen year!’ And she lifted it, though he would have prevented her, and put it to her lips. What harmony, besides her age and her simplicity, surrounded her, he did not know, but even in this fantastic action there was a something neither out of time nor place: a something which it seemed as if nobody else could have made as serious, or done with such a natural and touching air."

Half an hour after Stephen is back at work he happens to look out the window and sees the old woman still standing outside staring at the factory. We're told:

"He had been at his loom full half an hour, thinking about this old woman, when, having occasion to move round the loom for its adjustment, he glanced through a window which was in his corner, and saw her still looking up at the pile of building, lost in admiration. Heedless of the smoke and mud and wet, and of her two long journeys, she was gazing at it, as if the heavy thrum that issued from its many stories were proud music to her."

After work is over for the day, Stephen wanders the streets, trying to avoid going home to his drunken wife. As he wanders, Stephen imagines the pleasant, happy home he could share with Rachael if only he were free to remarry. I was thinking about Stephen, Rachael, and his wife. Earlier we were told that Stephen was forty and Rachael was thirty-five. Stephen tells Bounderby that he was twenty-one and his wife was twenty when they married, and Stephen and Rachael talk about being "old" friends, so did they all know each other when they were children? Or perhaps would Rachael have been a school friend of Stephen's wife? I don't know. Yet.

First things first: Turtle soup is a dish I have never yet enjoyed but then I am sure I would like it as I generally like eating fish, cockles and mussels and the like. However, turtle soup is probably outlawed by now because turtles might be an endangered species, I don't know. And Kim - treat yourself to a dish of smoked eel and you will know why I like it so much!

First things first: Turtle soup is a dish I have never yet enjoyed but then I am sure I would like it as I generally like eating fish, cockles and mussels and the like. However, turtle soup is probably outlawed by now because turtles might be an endangered species, I don't know. And Kim - treat yourself to a dish of smoked eel and you will know why I like it so much!Back to Chapter 11: I must confess that it also grated on me to see Stephen go to Bounderby in order to get his advice - but maybe as Stephen's employer, Bounderby was the most natural person for him to turn to. It would have been cleverer, maybe, to ask a more learned man like Mr. Gradgrind but probably Stephen does not know him well enough to ask his advice on such a personal matter.

From what I gather from the notes in my Penguin edition, it was indeed a very costly affair to get a divorce so that one can say that in this respect not everyone was equal before the law and that rich men could buy themselves out of an unhappy marriage whereas poor people couldn't. Dickens regarded this as an injustice and therefore wanted to include this point in Hard Times. According to Angus Calder's notes in the Penguin edition, this point was so important to Dickens that he double-underlined the words "Law of Divorce" in the plan of this instalment.

I would also think that making divorces unreachable for working class people was a social-political question for people like Bounderby in that it granted them stability with regard to the circumstances of their workers' private lives. It was enough for them, in their betters' eyes, to beget and raise children as future workers, and self-fulfilment was definitely not part of the parcel. One might have argued that allowing them to divorce would also encourage them to seek personal fulfilment in other aspects of their lives and it would also put into question the values of family and religion. This attitude is probably also mirrored in Mrs. Sparsit's terrified reaction.

As to the identity of the mysterious woman in Chapter 12, I have quite another guess - namely (mind, it's just a guess) that (view spoiler)

As to the identity of the mysterious woman in Chapter 12, I have quite another guess - namely (mind, it's just a guess) that (view spoiler)

Well, that's me told: I couldn't access the spoilers. Actually, Tristram, I realise that a particular thought had struck me too.

Well, that's me told: I couldn't access the spoilers. Actually, Tristram, I realise that a particular thought had struck me too.I agree, Kim, about the awfully bleak description of the town. Oh my word, if I lived in a place like that the depression alone would kill me. It's like one of the horrible dystopian, futuristic novels e.g. Cormac McCarthy's 'The Road'. I know that this is a very popular book and writer, so shoot me now! :p

I would like Bounderby to change places with Stephen for a month in the company of the grand, inebriated lady and ask him then whether or not he agrees with divorce. What an abnoxious, supercilious man! And what is Mrs Sparsit doing there? I can't help thinking that there's more to her story.

Kim wrote: "it is more of a mystery why anyone would worship Bounderby the way she does."

Kim wrote: "it is more of a mystery why anyone would worship Bounderby the way she does."That wasn't much of a mystery for me. He gave them work, which counts for a lot in that day and age when the was no unemployment insurance, no social security, if you didn't work you didn't eat. Then he was willing to talk on a quite friendly basis with an employee -- if you're manufacturing tires in a factory in Ohio try going to the owner's house to talk with him about a personal problem. Good luck! Bounderby recognized him and knew (and remembered) something of his history, which shows that he didn't see his employees as just units of machinery but as people. And he's interested in the school, which shows a certain civic interest in the affairs of the town. All in all, it seems as though he was really, especially for the times, a quite humane and reasonable employer, a benefit to the city.

Hilary wrote: "I agree, Kim, about the awfully bleak description of the town. Oh my word, if I lived in a place like that the depression alone would kill me. ."

Hilary wrote: "I agree, Kim, about the awfully bleak description of the town. Oh my word, if I lived in a place like that the depression alone would kill me. ."But if you had been born and brought up in those times, it would just be your normal life, wouldn't it? When I moved from a rural area to New York City, I was amazed at the squalor, noise, rats, cramped apartments, etc. which my friends, who were not wealthy and lived in older apartment buildings very inconveniently broken up into small units, thought were quite normal and even comfortable housing. My sister and her husband though themselves lucky to have a one bedroom apartment with many thick layers of paint, old and leaky windows, very little closet space, an elevator that worked intermittently, steam radiators that made the place either too hot or too cold, but was within long walking distance of Columbia University. They though they were well off!

A lot of it is what you've grown used to.

Hilary wrote: "Well, that's me told: I couldn't access the spoilers. Actually, Tristram, I realise that a particular thought had struck me too.

Hilary wrote: "Well, that's me told: I couldn't access the spoilers. Actually, Tristram, I realise that a particular thought had struck me too.I agree, Kim, about the awfully bleak description of the town. Oh m..."

I am going to send you a personal message then which contains what I wrote as a spoiler. In case you don't want to read it, just don't open the personal message. ;-)

There is no doubt that you're right, Everyman, of course you are; thank the Lord! When I was growing up I stayed with different friends in our town. One friend lived in a terraced house. These were few and far between as it was only a small town. This particular friend was a foster child and had a very sad back story which upsets me to this day when I think of it. To me, although I realise now that the house was very cramped, it was no different from any house that I visited or stayed in overnight.

There is no doubt that you're right, Everyman, of course you are; thank the Lord! When I was growing up I stayed with different friends in our town. One friend lived in a terraced house. These were few and far between as it was only a small town. This particular friend was a foster child and had a very sad back story which upsets me to this day when I think of it. To me, although I realise now that the house was very cramped, it was no different from any house that I visited or stayed in overnight. When I reflect on the living conditions of a different friend there is a stark contrast. Her house was an old rambling mansion with stables and horses and servants; you name it. To me they were both the same except that my fostered friend had a very cross even wicked foster mother.

This friend (my fostered friend) and I used to go round houses at Hallowe'en, trick or treating. At my other friend's we rode horses. I was equally happy in both. In those days, my friends were happy regardless of where they

lived. The people with whom they lived made the difference; humble house or grand, my friend in the terraced house could not have been happy with a foster mother straight out of the pages of Roald Dahl.

Most of the housing was in the form of housing estates where there were small gardens in front and patches of garden or yards (by yards I mean cement not grass) at the back.

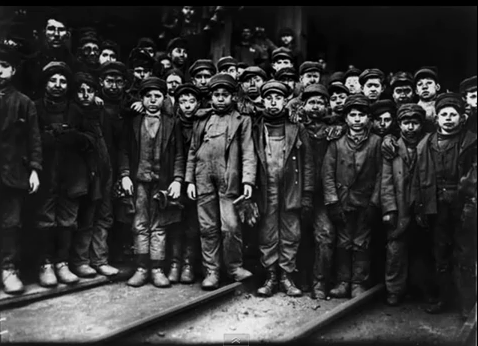

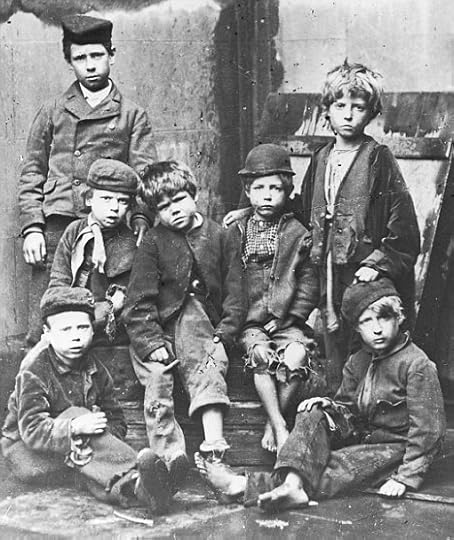

The photos that Kate has kindly posted for us are, however, on a whole different level. The eyes speak volumes. How could the children sleep with rumbling tummies and living in icy cold temperatures? There must have been many illnesses. It's a wonder that any survived. It was all they knew, but they could never become accustomed to it. They had no choice.

The divorce laws were certainly much different from today. The Marital Causes Act came into effect in 1857 and thus divorce became a matter for the civil courts. Before that, only the rich could get a divorce because the cost was high as noted. Prior to 1857 a divorce could only be granted by Parliament. Thus, if you wanted a divorce, it would be debated in Parliament. Too much dirty laundry for the rich/titled who, in all likelihood, had some form of what we today would consider a marital contract in place anyway.

The divorce laws were certainly much different from today. The Marital Causes Act came into effect in 1857 and thus divorce became a matter for the civil courts. Before that, only the rich could get a divorce because the cost was high as noted. Prior to 1857 a divorce could only be granted by Parliament. Thus, if you wanted a divorce, it would be debated in Parliament. Too much dirty laundry for the rich/titled who, in all likelihood, had some form of what we today would consider a marital contract in place anyway.

The meeting of Stephen and Bounderby is a strange one and for Stephen it does seem that there is no way out of his marriage. This chapter, like others before it in HT, takes on a feeling of mini-lecture or exploration of a topic. Stephen is stuck in his situation. Mr. Sparsit has her acidic moment of commentary on marriage by asking "Was it an unequal marriage, sir, in point of years?" Seems to me she is hinting at Bounderby's attentions towards Louisa. Mrs Sparsit and Stephen have already suffered the pains of a marriage gone wrong. Will it be that Bounderby and Louisa are soon to be on a marital path of happiness or hell?

The meeting of Stephen and Bounderby is a strange one and for Stephen it does seem that there is no way out of his marriage. This chapter, like others before it in HT, takes on a feeling of mini-lecture or exploration of a topic. Stephen is stuck in his situation. Mr. Sparsit has her acidic moment of commentary on marriage by asking "Was it an unequal marriage, sir, in point of years?" Seems to me she is hinting at Bounderby's attentions towards Louisa. Mrs Sparsit and Stephen have already suffered the pains of a marriage gone wrong. Will it be that Bounderby and Louisa are soon to be on a marital path of happiness or hell?It is also interesting to reflect on Dickens's own marital situation at the time.

The seemingly unusual obsession of respect for Bounderby of many people is expanded further with Stephen meeting the old woman in this chapter. She not only questions Stephen about Bounderby, but actually kisses Stephen's hand after he talks about Bounderby and his factory. Both this crone and Rachael are seen as touching Stephen's arm. Rachael and the crone; an angelic and a mysterious presence. What are we to make of it all?

The seemingly unusual obsession of respect for Bounderby of many people is expanded further with Stephen meeting the old woman in this chapter. She not only questions Stephen about Bounderby, but actually kisses Stephen's hand after he talks about Bounderby and his factory. Both this crone and Rachael are seen as touching Stephen's arm. Rachael and the crone; an angelic and a mysterious presence. What are we to make of it all?

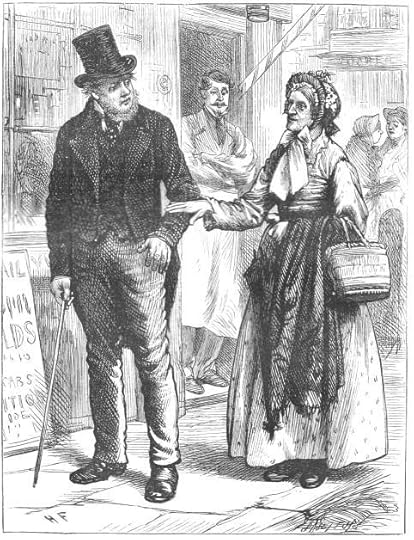

There aren't many illustrations for this installment, here is one by Harry French, the only one he did for this section:

There aren't many illustrations for this installment, here is one by Harry French, the only one he did for this section:

"He Felt A Touch Upon His Arm"

Chapter 12

Harry French

Text Illustrated:

"Old Stephen descended the two white steps, shutting the black door with the brazen door-plate, by the aid of the brazen full-stop, to which he gave a parting polish with the sleeve of his coat, observing that his hot hand clouded it. He crossed the street with his eyes bent upon the ground, and thus was walking sorrowfully away, when he felt a touch upon his arm.

It was not the touch he needed most at such a moment—the touch that could calm the wild waters of his soul, as the uplifted hand of the sublimest love and patience could abate the raging of the sea—yet it was a woman’s hand too. It was an old woman, tall and shapely still, though withered by time, on whom his eyes fell when he stopped and turned. She was very cleanly and plainly dressed, had country mud upon her shoes, and was newly come from a journey. The flutter of her manner, in the unwonted noise of the streets; the spare shawl, carried unfolded on her arm; the heavy umbrella, and little basket; the loose long-fingered gloves, to which her hands were unused; all bespoke an old woman from the country, in her plain holiday clothes, come into Coketown on an expedition of rare occurrence. Remarking this at a glance, with the quick observation of his class, Stephen Blackpool bent his attentive face—his face, which, like the faces of many of his order, by dint of long working with eyes and hands in the midst of a prodigious noise, had acquired the concentrated look with which we are familiar in the countenances of the deaf—the better to hear what she asked him."

Thanks for the illustration Kim. Is it me or is Stephen somewhat overdressed for a factory hand heading back to his dreary job?

Thanks for the illustration Kim. Is it me or is Stephen somewhat overdressed for a factory hand heading back to his dreary job?

Since I can't seem to find illustrations for this week, I give you this instead. There are no spoilers, I checked. :-)

Since I can't seem to find illustrations for this week, I give you this instead. There are no spoilers, I checked. :-)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0Mqy...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nk5KI...

Hilary wrote: "Thank you, Tristram. That is very kind of you. I'd very much appreciate that."

Hilary wrote: "Thank you, Tristram. That is very kind of you. I'd very much appreciate that."You're most welcome!

Kim wrote: "Since I can't seem to find illustrations for this week, I give you this instead. There are no spoilers, I checked. :-)

Kim wrote: "Since I can't seem to find illustrations for this week, I give you this instead. There are no spoilers, I checked. :-)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0Mqy...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v..."

I had a look at the first clip, Kim, and was immediately caught by the atmosphere. The speaker has a brilliant voice, and the pictures - maybe with the exception that I think the text describes Sissy as a dark-haired girl - really make the novel come to life. It's wonderful to see how people use their creativity to make Dickens become known to a wider audience!

Peter wrote: "Mr. Sparsit has her acidic moment of commentary on marriage by asking "Was it an unequal marriage, sir, in point of years?" Seems to me she is hinting at Bounderby's attentions towards Louisa."

Peter wrote: "Mr. Sparsit has her acidic moment of commentary on marriage by asking "Was it an unequal marriage, sir, in point of years?" Seems to me she is hinting at Bounderby's attentions towards Louisa."That's a really good point, Peter! My first idea was that Mrs. Sparsit was reflecting on her own melancholy foray into married life and thought that if her own marriage failed because of a wide difference in age, it would also be the case with Stephen. But she might indeed use this situation in order to covertly criticize the marriage plans of her employer. Maybe she has the ambition to rise from a housekeeper to her employer's wife? I think that Mrs. Sparsit has, as we would say in German, put Mr. Bounderby in her pocket already, i.e. she controls him and can make him do what she wants (by playing on his vanity).

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Mr. Sparsit has her acidic moment of commentary on marriage by asking "Was it an unequal marriage, sir, in point of years?" Seems to me she is hinting at Bounderby's attentions toward..."

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Mr. Sparsit has her acidic moment of commentary on marriage by asking "Was it an unequal marriage, sir, in point of years?" Seems to me she is hinting at Bounderby's attentions toward..."Yes. The Sparsit-Bounderby relationship is both weird and puzzling. To me it seems somewhat passive-aggressive. Both Sparsit and Bounderby want to dominate the other, for their own reasons, but to do so, act out, in various manners, an "oh, poor me" role. A good case for a good psychologist, or psychiatrist.

Kim wrote: "There aren't many illustrations for this installment, here is one by Harry French, the only one he did for this section:."

Kim wrote: "There aren't many illustrations for this installment, here is one by Harry French, the only one he did for this section:."Oh goodness, a mill hand would not be wearing a top hat and carrying a cane, especially not since he came from the mill and is returning back to it. Nor would he be wearing a cravat, waistcoat, and tailcoat. This is totally absurd!

I agree with Tristram's supposition and look forward to seeing it come to light.

I agree with Tristram's supposition and look forward to seeing it come to light. I also agree that the drawing above is completely inaccurate for someone of Stephen's station. Not at all the picture in my head.

Great observation on Mrs. Sparsit's comments, Peter.

One question I don't think anyone has asked yet - why is the mysterious old woman familiar to Stephen? Have they met before, or does she resemble someone else he knows? She doesn't seem to recognize him, leading me to think she looks like someone else. I'm sure I'm not the only one coming to a certain conclusion....

The conversation between the two of them re: Stephen's happiness is interesting to me. I have no insights to share about that - just thought I'd throw it out there. :-)

Dickens includes some Biblical imagery in describing the factory, namely:

before pale morning showed the monstrous serpents of smoke trailing themselves over Coketown.

their tall chimneys rising up into the air like competing Towers of Babel

Serpent symbolism is never a good thing, of course. I haven't studied the Tower of Babel story, but reread it after seeing it referenced here (it's Genesis 11: 1-9). It seems to me that the Shinarians (I'm probably making that word up) were working together and communicating a little too well, which God saw as a threat. God didn't want their tower to reach heaven, so he made it so they could no longer communicate and would stop building the tower. (Kind of a weeny move for God, I think, but that's another book and another discussion!)

So, how does this fit in with our story? Does it represent the rise of the working classes and the threat they pose to the aristocracy? If so, does Dickens see it as a good thing or a bad one?

Or maybe Dickens was just trying to illustrate that the factory had a big tower. >>shrug<< What do I know? But I noticed it, and thought there might be something there.

I got thinking when I was reading your comments about the way Stephen is dressed in the above illustration, I do agree with you all - but I had the feeling I saw someone in another illustration who looked exactly like Stephen and reading some commentary on his clothing, I usually pay more attention to the commentary then the illustration looking for and removing spoilers. Anyway, I went back and found this illustration and commentary from last week's installment:

I got thinking when I was reading your comments about the way Stephen is dressed in the above illustration, I do agree with you all - but I had the feeling I saw someone in another illustration who looked exactly like Stephen and reading some commentary on his clothing, I usually pay more attention to the commentary then the illustration looking for and removing spoilers. Anyway, I went back and found this illustration and commentary from last week's installment:

From the commentary:

"Stephen's beard, top hat, and tail-coat are plausible, given the historical context in which the artist drew them. Even the working class attempted to maintain a respectable appearance by shopping in second-hand clothing shops, acquiring what had been some seasons previous fashionable and what still had considerable wear left; we note that Stephen's coat seems somewhat out-of-date compared to the fuller frock-coats worn by Gradgrind and Bounderby."

Despite what the commentary says I still have trouble picturing Stephen working at the factory all day dressed like that.

Good catch, Kim. I admit, I don't always read the commentary under the pictures you post, and I missed this one. I also didn't notice the top hat on the table in the background, which - to a 21st century viewer - seems very formal, and part of what makes the French drawing a bit jarring for us, perhaps.

Good catch, Kim. I admit, I don't always read the commentary under the pictures you post, and I missed this one. I also didn't notice the top hat on the table in the background, which - to a 21st century viewer - seems very formal, and part of what makes the French drawing a bit jarring for us, perhaps.

Thanks. When I looked closer at the drawing and got the feeling I had seen the man before, I actually thought it had been Bounderby that I saw, but it really was Stephen. Not the one in my mind though.

Thanks. When I looked closer at the drawing and got the feeling I had seen the man before, I actually thought it had been Bounderby that I saw, but it really was Stephen. Not the one in my mind though.

Great observations concerning Stephen's dress when he is at home. Somehow I doubt a factory hand would have the financial resources, let alone the energy, to change his clothes and be properly dressed for the evening. But there are the illustrations that suggest otherwise.

Great observations concerning Stephen's dress when he is at home. Somehow I doubt a factory hand would have the financial resources, let alone the energy, to change his clothes and be properly dressed for the evening. But there are the illustrations that suggest otherwise.When I have seen the early photographs of the mill town workers they have not been wearing top hats and coats with tails. Many do wear soft peak caps and do wear a vest over their shirts.

Perhaps we need to put detective Bucket on "The Case of the Over-Dressed Mill Worker."

Mary Lou wrote: "I agree with Tristram's supposition and look forward to seeing it come to light.

Mary Lou wrote: "I agree with Tristram's supposition and look forward to seeing it come to light. I also agree that the drawing above is completely inaccurate for someone of Stephen's station. Not at all the pict..."

Mary Lou

No need to shrug. I think your observation and suggestions concerning the Tower of Babel symbolism are very insightful. I too see HT as a novel in which Dickens takes a long, critical look at society and how the progress of the industrial world was, in many ways, moving far away from the more paternalistic world of earlier English times. HT was written just after the Great Exhibition of 1851. The glories of the new age in England were all paraded for the world to see; the disruptions this new world caused were tucked away.

Here we go:

Here we go:

The caption says "Victorian factory workers on a standard mill cart".

"A 17th century Witney trade token featuring a wool sack, evidence of the importance of the wool trade to the town."

And under textile factories:

Thanks Kim.

Thanks Kim.I know that it took longer to take a picture back in the 19C but all those grim, serious, hard faces certainly tell their own story don't they?

I was struck as well by their boots. Hard, solid and they seem so heavy. I recall what Estella had to say about Pip's boots in GE.

In Chap 11, Bounderby and Sparsit appear increasingly hypocritical to me. Bounderby would never have risen above labourer if he followed his own advice to Stephen to only "mind his piece-work", and his pretence of humility is exaggerated further by accusing (in his passive-aggressive way -- I think you're right about this trait, Peter) Stephen of hankering after turtle soup, etc, while he drinks his sherry in front of him.

In Chap 11, Bounderby and Sparsit appear increasingly hypocritical to me. Bounderby would never have risen above labourer if he followed his own advice to Stephen to only "mind his piece-work", and his pretence of humility is exaggerated further by accusing (in his passive-aggressive way -- I think you're right about this trait, Peter) Stephen of hankering after turtle soup, etc, while he drinks his sherry in front of him. Mrs. Sparsit's shock and dejection by the "immorality of the people" contrasts her own marriage, which ended in separation just after the honeymoon, and although she suffered its debt, it was a relatively short marriage, compared to Stephen's. She was released by death -- the only other way out, besides divorce. It leaves me wondering just how old she is (Stephen at 40 is already old), and whether, as others suggested, she has marital hopes for Bounderby herself, or just wishes to prevent him marrying anyone else. What a pair!

I agree with Tristram's guess for the old woman's identity. Stephen's familiarity with her face, reminded me of Guppy's sense of deja vu seeing Lady D's portrait in BH.

Mary Lou wrote: "So, how does this fit in with our story? Does it represent the rise of the working classes and the threat they pose to the aristocracy? If so, does Dickens see it as a good thing or a bad one? .."

Mary Lou wrote: "So, how does this fit in with our story? Does it represent the rise of the working classes and the threat they pose to the aristocracy? If so, does Dickens see it as a good thing or a bad one? .."Thanks for pointing out the interesting symbolism, Mary Lou. I also took the Towers of Babel comparison to show that the factories have made their workers' lives meaningless, as well as literally deafening them with its racket.

Kim wrote: "Here we go:

Kim wrote: "Here we go:The caption says "Victorian factory workers on a standard mill cart".

"A 17th century Witney trade token featuring a wool sack, evidence of the importance of the wool trade to the t..."

Just kids in the last photo... :(

Hilary wrote: "Love the 'German' phrase. And the German, please? ..."

Hilary wrote: "Love the 'German' phrase. And the German, please? ..."Hilary,

the German is "jemanden in die Tasche stecken" for "to put somebody into one's pocket", or "jemanden in der Tasche haben" for "to have somebody in one's pocket". We also have "den Papst in der Tasche haben" (to carry the Pope in one's pocket) when somebody is very good at something and you think that he owes it all to luck and serendipity.

Vanessa and Mary Lou,

Vanessa and Mary Lou,the idea about the old woman's identity seems to get further support by the fact that Stephen not only thinks he has seen the woman somewhere before but that, as the text says, he has also not quite liked her. ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Vanessa and Mary Lou,

Tristram wrote: "Vanessa and Mary Lou,the idea about the old woman's identity seems to get further support by the fact that Stephen not only thinks he has seen the woman somewhere before but that, as the text say..."

True.

Vanessa, about the children in the picture, when I started searching for pictures of "Victorian laborers clothing" or something like that, all I would get was pictures of children. I had to keep searching by changing the words around and making sure I put the word adult or men in there somewhere and I still got mostly pictures of children. Hundreds of them must have worked at awful jobs, it is sad.

Here are a few, the first was titled "Britian's child slaves"

"Children at work in London Hosiery Mill"

"Child labor in America"

Oh, my. After my comments on the fact that the earlier pictures seemed to suggest the factory workers wore very heavy shoes, these pictures show children in horrid working conditions wearing no shoes. And to think that Britain actually were "upgrading" their labour laws in the mid 19C.

Oh, my. After my comments on the fact that the earlier pictures seemed to suggest the factory workers wore very heavy shoes, these pictures show children in horrid working conditions wearing no shoes. And to think that Britain actually were "upgrading" their labour laws in the mid 19C.

Peter wrote: "Oh, my. After my comments on the fact that the earlier pictures seemed to suggest the factory workers wore very heavy shoes, this pictures show children in horrid working conditions wearing no shoe..."

Peter wrote: "Oh, my. After my comments on the fact that the earlier pictures seemed to suggest the factory workers wore very heavy shoes, this pictures show children in horrid working conditions wearing no shoe..."Are (were) these children any worse off than the children in southeast Asia that make many of our electronic gadgets today?

Everyman, thank you for reminding me of the plight of our 'neighbours'. It shocks me how easily I forget! And believe me I have no excuse. We have, since early 1999, been visiting regularly orphanages in South India. (Sorry if I've said this before - my memory is terrible). We have been plunged into even greater poverty (not us personally, though it might have been us!) in various other locations. The kids in Tamil Nadu are happy and slowly there has been progress. Actually, when I say slowly, they work much more quickly than many of their Western counterparts.

Everyman, thank you for reminding me of the plight of our 'neighbours'. It shocks me how easily I forget! And believe me I have no excuse. We have, since early 1999, been visiting regularly orphanages in South India. (Sorry if I've said this before - my memory is terrible). We have been plunged into even greater poverty (not us personally, though it might have been us!) in various other locations. The kids in Tamil Nadu are happy and slowly there has been progress. Actually, when I say slowly, they work much more quickly than many of their Western counterparts. Anyhow, digressions aside (sic) the point I wanted to make was that these kids are barefoot. The occasional child has flip flops which will be displayed with great pride.

Of course these children are not white Anglo-Saxon or white anything else for that matter; they live far, far away so "let them eat cake"!!!

Indeed, they'd be very fortunate to get a slavish factory job. After all they would have clogs in which to click homewards; this would be, for them, a source of great pride.

Blessed are we ...

Kim wrote: "Vanessa, about the children in the picture, when I started searching for pictures of "Victorian laborers clothing" or something like that, all I would get was pictures of children...."

Kim wrote: "Vanessa, about the children in the picture, when I started searching for pictures of "Victorian laborers clothing" or something like that, all I would get was pictures of children...."Truly awful, in any era. They were probably cheaper than adults. Thanks for the added info and photos, Kim. Oddly, in the top pic, the boys on the right (standing & sitting, who look like they could be brothers) are almost just like I imagine some of Dickens' poor boy characters -- Oliver Twist, David Copperfield (although he would be dressed better, at least), etc. Speaking of deja vu moments! Maybe I've watched too much BBC :)

I once did a school project on Child Labour in England During the Industrial Revolution, and so I was familiar with some of the photos above. One of the photos I found most terrible was that of a group of boys aged between 10 and 15 maybe, each one of whom had lost a limb (arm or leg) due to accidents at work, and who would now no longer be employed as they were no longer useful.

I once did a school project on Child Labour in England During the Industrial Revolution, and so I was familiar with some of the photos above. One of the photos I found most terrible was that of a group of boys aged between 10 and 15 maybe, each one of whom had lost a limb (arm or leg) due to accidents at work, and who would now no longer be employed as they were no longer useful.In fact they used small children as "Scavengers", i.e. these boys had to creep under the mechanic looms to pick up any piece of cotton that would have got stuck in the machine and threatened to block it. They did not stop the looms because that would have cost valuable time and money, and so the children had to be very quick and nimble in order not to get caught in the machine themselves. That's just one example of how maiming accidents at work could occur.

Tristram wrote: "I once did a school project on Child Labour in England During the Industrial Revolution, and so I was familiar with some of the photos above. One of the photos I found most terrible was that of a g..."

Tristram wrote: "I once did a school project on Child Labour in England During the Industrial Revolution, and so I was familiar with some of the photos above. One of the photos I found most terrible was that of a g..."Makes Dickens' work at a blacking factory seem like a picnic.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I once did a school project on Child Labour in England During the Industrial Revolution, and so I was familiar with some of the photos above. One of the photos I found most terribl..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I once did a school project on Child Labour in England During the Industrial Revolution, and so I was familiar with some of the photos above. One of the photos I found most terribl..."Yeas, but still not like a picnic where one is likely to enjoy oneself - probably more like a picnic in the family circle ;-)

Everyman wrote: "Are (were) these children any worse off than the children in southeast Asia that make many of our electronic gadgets today? "

Everyman wrote: "Are (were) these children any worse off than the children in southeast Asia that make many of our electronic gadgets today? "No, they weren't.

Hilary wrote: "Tristram, thanks so much for the German translations. I shall try, try, try to remember them! :-)"

Hilary wrote: "Tristram, thanks so much for the German translations. I shall try, try, try to remember them! :-)"Good luck ;-)

Kim,

Kim,those are the bad effects of globalization, and it is dreadful that other countries seem to have to go through the same stages of Industrial Revolution that Europe and America had to go through. And yet, it is probably not the same development since the old industrial countries did not have to compete with well-industrialized neighbours at the time. I doubt that working conditions will ever improve in Asia.

Relative to the question of whether having a bottle of poison on the table was unrealistic, I ran across this little item today. Granted, a century before Dickens, but did that much change in the interim?

Relative to the question of whether having a bottle of poison on the table was unrealistic, I ran across this little item today. Granted, a century before Dickens, but did that much change in the interim?A journeyman joiner in Kelso, having procured some arsenic for poisoning rats, mixed it amongst oatmeal, and laid it in his tool chest. His wife accidentally finding it, and not knowing the meal contained poison put it into their porridge on Monday morning last. Her eldest child who was about three years of age, upon taking the porridge, said they were bad, and would take no more, but she and a child she was nursing took a few spoonfuls of them, which they had no sooner done, than they were seized with violent reaching [sic] and vomiting, attended with a heat and pricking pain in the stomach. The husband coming in soon after for his breakfast, she told him what she had done, when he exclaimed, “You are all poisoned!” He immediately run [sic] for a doctor, who made use of every proper means to expel the poison, which was happily effected, as they are now in a fair way of recovery.

— from The Pennsylvania Packet Friday, Nov. 18, 1785, courtesy of Jeff Burks

We have now arrived at Chapter 11, titled "No Way Out' and I find myself rather amazed that Stephen's idea for coming up with a solution to his problem with his drunken wife - I still don't see any mention of opium - is to go to Bounderby for advice. The working people of the town certainly seem to have a different opinion of Mr. Bounderby than I have. He is the last person I would go to for advice on just about anything I can think of. I found the first line of the chapter terribly depressing fairy palaces and all:

"The Fairy palaces burst into illumination, before pale morning showed the monstrous serpents of smoke trailing themselves over Coketown. A clattering of clogs upon the pavement; a rapid ringing of bells; and all the melancholy mad elephants, polished and oiled up for the day’s monotony, were at their heavy exercise again."

Then we have Stephen bent over his loom for the entire day and this description of the day as it becomes light:

"The day grew strong, and showed itself outside, even against the flaming lights within. The lights were turned out, and the work went on. The rain fell, and the Smoke-serpents, submissive to the curse of all that tribe, trailed themselves upon the earth. In the waste-yard outside, the steam from the escape pipe, the litter of barrels and old iron, the shining heaps of coals, the ashes everywhere, were shrouded in a veil of mist and rain."

Between Stephen making my back and shoulders hurt just thinking of bending over at his job all day, the coal and ashes, the rain and most of all breathing in that smoke all the time, the beginning of this chapter is extremely bleak and I can't see anything good coming out of it, which it doesn't. When the workers take their noon break, which rather surprised me that they had got an hour's break, but I imagine they weren't paid for it, Stephen goes to see Mr. Bounderby. The entire discussion between the two of them brought me back to our talking about why the people in the town looked up to Bounderby. Bounderby treats Stephen just the way you would expect a bully to treat Stephen. First he accuses him of wanting something, of being there to complain,

"You don’t expect to be set up in a coach and six, and to be fed on turtle soup and venison, with a gold spoon, as a good many of ’em do!’ Mr. Bounderby always represented this to be the sole, immediate, and direct object of any Hand who was not entirely satisfied; ‘and therefore I know already that you have not come here to make a complaint. Now, you know, I am certain of that, beforehand.’ "

Turtle soup sounds awful to me, although Tristram probably loves it, he loves smoked eel of all things, or maybe it was fried, I forget. And of course before Stephen can get a word out of why he is there Mr. Bounderby has to take a moment to tell Stephen, as he tells everyone, that Mrs. Sparsit was a high born lady, even though now she works for him. Finally Stephen tells the story of his marriage and after telling Bounderby that he had read about divorce in the newpapers, he asks how he can go about getting one. During the early part of this conversation Bounderby says this:

‘I have heard all this before,’ said Mr. Bounderby. ‘She took to drinking, left off working, sold the furniture, pawned the clothes, and played old Gooseberry.’

There were two things I noticed when I read this. First I wondered what playing old Gooseberry was, so of course I looked it up:

"A gooseberry could be a fool or simpleton, borrowed from the ancient dish gooseberry fool. Old Gooseberry was the devil — an exact parallel to Old Harry — perhaps using the word in the sense of a being who could with care be outwitted. To play old gooseberry meant to make mischief or to defeat, destroy or ruin, or to seriously mismanage some matter:

You go and play old gooseberry with your constitution, you know, pitch your liver to Old Harry, and make ducks and drakes of your nervous system; — why, bless my soul, you know, you’ll be dead in two-two’s.

The Colonial Monthly (Australia), Mar. 1869."

The other thing was Bounderby saying "she took to drinking", that reminded me of the opium addiction mentioned in the earlier commentary, it still isn't mentioned in the book, Stephen hasn't mentioned it in this chapter either. So I wonder, is that still to come?

Bounderby tells Stephen that divorce is impossible, that "there’s a sanctity in the relation” of marriage that “must be kept up.” He does go on to admit however, that there is a law allowing for two people to get divorced but it is only for the rich.

‘Now, I tell you what!’ said Mr. Bounderby, putting his hands in his pockets. ‘There is such a law.’

Stephen, subsiding into his quiet manner, and never wandering in his attention, gave a nod.

‘But it’s not for you at all. It costs money. It costs a mint of money.’

‘How much might that be?’ Stephen calmly asked.

‘Why, you’d have to go to Doctors’ Commons with a suit, and you’d have to go to a court of Common Law with a suit, and you’d have to go to the House of Lords with a suit, and you’d have to get an Act of Parliament to enable you to marry again, and it would cost you (if it was a case of very plain sailing), I suppose from a thousand to fifteen hundred pound,’ said Mr. Bounderby. ‘Perhaps twice the money.’

‘There’s no other law?’

‘Certainly not.’

I would like to know if this is the truth or if Bounderby is lying to Stephen for some reason. Would it really cost a thousand pounds or more? Would it be easier for a rich person to get a divorce than a poor person? I would think it wasn't easy for anyone to get one back then but I'm not sure. And what does it matter to Bounderby whether Stephen gets divorced or not? Stephen now says that "tis all a muddle" and the sooner he dies the better. This gives Bounderby a chance for one last speech before Stephen leaves and the chapter ends:

‘Now, I’ll tell you what!’ Mr. Bounderby resumed, as a valedictory address. ‘With what I shall call your unhallowed opinions, you have been quite shocking this lady: who, as I have already told you, is a born lady, and who, as I have not already told you, has had her own marriage misfortunes to the tune of tens of thousands of pounds—tens of Thousands of Pounds!’ (he repeated it with great relish). ‘Now, you have always been a steady Hand hitherto; but my opinion is, and so I tell you plainly, that you are turning into the wrong road. You have been listening to some mischievous stranger or other—they’re always about—and the best thing you can do is, to come out of that. Now you know;’ here his countenance expressed marvellous acuteness; ‘I can see as far into a grindstone as another man; farther than a good many, perhaps, because I had my nose well kept to it when I was young. I see traces of the turtle soup, and venison, and gold spoon in this. Yes, I do!’ cried Mr. Bounderby, shaking his head with obstinate cunning. ‘By the Lord Harry, I do!’

With a very different shake of the head and deep sigh, Stephen said, ‘Thank you, sir, I wish you good day.’ So he left Mr. Bounderby swelling at his own portrait on the wall, as if he were going to explode himself into it; and Mrs. Sparsit still ambling on with her foot in her stirrup, looking quite cast down by the popular vices."