The Pickwick Club discussion

Hard Times

>

Part I Chapters 13 - 14

Chapter 14 is entitled „The Great Manufacturer“, and at first I thought this would be Mr. Bounderby but while reading on, I found out that it is actually a metaphor referring to Time, who works its changes on some of our youthful characters – Louisa, young Thomas and Sissy Jupe:

Chapter 14 is entitled „The Great Manufacturer“, and at first I thought this would be Mr. Bounderby but while reading on, I found out that it is actually a metaphor referring to Time, who works its changes on some of our youthful characters – Louisa, young Thomas and Sissy Jupe:”Time, with his innumerable horse-power, worked away, not minding what anybody said, and presently turned out young Thomas a foot taller than when his father had last taken particular notice of him.”

It’s quite funny how the narrator here implies that Mr. Gradgrind has a rather matter-of-fact relationship with his children. In this chapter we learn that – I’m trying to adopt a Gradgrindian, systematic approach:

a) that Sissy Jupe has grown to become a pretty young woman, who may not be at all successful at school and who may still cling to the notion that her father will come back one day – that’s why she still has the bottle of Nine Oils ready – but who has not only won the favour of Mrs. Gradgrind but also that of her husband, who – as the text says – likes her too well to hold her in contempt for her lack of learning;

b) that Mr. Gradgrind has human feelings – in fact he likes Sissy;

c) that Mr. Gradgrind has finally succeeded in becoming a Member of Parliament;

d) that Louisa, too, has grown to become a young woman and that Mr. Gradgrind one day announces that he is going to have a word with her the next day. Judging from Louisa’s cold hands, she might have an idea what the talk is going to be about, and she may not like it too much;

e) that Thomas has grown to be a young man, not a very prepossessing one, though, and that he has finally moved to Mr. Bounderby to start an apprenticeship at the Bank. We also cannot help noticing that young Thomas callously exploits Mr. Bounderby’s soft spot for his sister in order to make this bully of humility dance to his tune. Young Thomas clearly expects his sister to give her hand in marriage to his employer and he is looking forward to all the advantages this union might bring to him. When he asks Louisa not to forget how fond she is of him, we might well cringe at this young cadger’s slickness and ruthlessness;

f) that Mr. Gradgrind and Mr. Bounderby have a private talk in the Bank – probably about the very same subject Mr. Gradgrind wants to see his daughter about;

g) that they preferred having their talk in the Bank in order to prevent Mrs. Sparsit from eavesdropping upon them.

I must say that doing things in the Gradgrindian way is a swift way of dealing with a chapter. I should do it more often ;-)

Being Valentine's Day, who could not love Rachael? I fully agree with Tristram that HT seems to have its chapters focus much more on a cause, an idea or a person than we have been used to in our earlier novels. Indeed, Rachael is portrayed as an angel in her appearance, her activity and even the light that seems to radiate and surround her. I think Dickens has more in mind than simply portraying her goodness.

Being Valentine's Day, who could not love Rachael? I fully agree with Tristram that HT seems to have its chapters focus much more on a cause, an idea or a person than we have been used to in our earlier novels. Indeed, Rachael is portrayed as an angel in her appearance, her activity and even the light that seems to radiate and surround her. I think Dickens has more in mind than simply portraying her goodness. First, there is a very clear and distinct contrast created between Rachael and Stephen's wife. The point where Stephen's wife reaches for the poison is central. Perhaps Stephen would have watched his wife poison herself. The fact is Rachael prevents it. I don't think we should think any less of Stephen; I think we should think all the more of Rachael. Clearly, Stephen and Rachael's friendship goes back years and it is broadly hinted by Dickens that were it not for the fact that Mrs. Blackpool is still alive, Stephen and Rachael may well acknowledge their mutual affection openly.

There is an unhappy relationship and possible marriage brewing between Bounderby and an unwilling Louisa. There is already a soulless marriage between Gradgrind and his wife. There is, certainly, a strange relationship between Mrs. Sparsit and Bounderby. We also have Sissy whose love for her father seems, at this point in time, unacknowledged, and we are not yet through half the novel. Dickens is moving us, I feel, towards a series of revelations concerning relationships, both failed and possible.

One item that may help tie these various seemingly unattached threads together is the symbol of a bottle. In Sissy's hand, the bottle of nine oils symbolizes her faith in love and the belief that her father will return to her. In the case of the bottle of poison, it symbolizes a poisoned relationship between Stephan and his wife.

Great work, Tristram! The Gradgrindian approach to chapter 14 made me smirk. ;-). :

Great work, Tristram! The Gradgrindian approach to chapter 14 made me smirk. ;-). :a). I like it

b). It's very efficient

c). It can be somewhat exhausting

d). Re c) I shall stick with descriptive writing for the time being e.g. In place of 'The cat was sorry' I shall say 'The dirty, matted, smelly cat

was grovellingly, pathetically and ear-scratchingly sorry. ;-)

I love Rachael, as do you Peter, but then how could it be otherwise?!!! While taking into account that none of us is perfect, (except for me!), Rachael demonstrates her selflessness

In looking after Mrs Blackpool, the one person who stands between her and her true love. Indeed, I believe that if her potential nemesis were to recover she would sincerely rejoice. I don't believe that Schadenfreude is part of Rachael's vocabulary. (Well no, it's unlikely to have been anyhow. :D)

I'm looking forward to finding out how all the relationships pan out, whether happy or sad ...

Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."

Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."I took it to be some sort of disinfectant perhaps?

Peter wrote: "The point where Stephen's wife reaches for the poison is central. Perhaps Stephen would have watched his wife poison herself. The fact is Rachael prevents it.."

Peter wrote: "The point where Stephen's wife reaches for the poison is central. Perhaps Stephen would have watched his wife poison herself. The fact is Rachael prevents it.."Which is a particularly telling insight into her character, because if she let Stephen's wife drink the poison it would be wrong, and perhaps a sin, but she must also know that it would make both her and Stephen much happier, and perhaps even his wife since she seems not to have any joy in her life or any expectation of future joy.

It's an interesting ethical question. Should one intervene to prevent an act which would under normal circumstances be a wrong but in the particular case would substantially increase human happiness?

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "The point where Stephen's wife reaches for the poison is central. Perhaps Stephen would have watched his wife poison herself. The fact is Rachael prevents it.."

Everyman wrote: "Peter wrote: "The point where Stephen's wife reaches for the poison is central. Perhaps Stephen would have watched his wife poison herself. The fact is Rachael prevents it.."Which is a particular..."

A good question, Everyman. Dickens's early novels are painted in either black or white. As he matures there are certainly more shading to both some characters and themes. Perhaps the answer to your ethical question occurs later in the novel.

The chapter "The Great Manufacturer" begins with great style. Dickens's use of anaphora, "so much ..." four times in the first sentence, the word "time" at the beginning of four paragraphs and then the phrases "Louisa/Tom is becoming" and then finishing the sentence with "almost a young woman/man" create a subtle yet persistent rhythm that matches the passage of time that Dickens is conveying to the reader. This style also helps set up the next paragraph that discusses Sissy's continuous loving nature, but apparent total lack of progress in the repressive school system. Nevertheless, as Tristram noted ( in a very utilitarian manner!) Gradgrind is seen as having soft and caring feelings for Sissy. Gradgrind has a heart, buried somewhere.

The chapter "The Great Manufacturer" begins with great style. Dickens's use of anaphora, "so much ..." four times in the first sentence, the word "time" at the beginning of four paragraphs and then the phrases "Louisa/Tom is becoming" and then finishing the sentence with "almost a young woman/man" create a subtle yet persistent rhythm that matches the passage of time that Dickens is conveying to the reader. This style also helps set up the next paragraph that discusses Sissy's continuous loving nature, but apparent total lack of progress in the repressive school system. Nevertheless, as Tristram noted ( in a very utilitarian manner!) Gradgrind is seen as having soft and caring feelings for Sissy. Gradgrind has a heart, buried somewhere.Gradgrind is now the Member of Parliament for Coketown. To the original readers this would signal how the rising industrial class was slowly assuming its place in Parliament that was, in the past, the sole preserve of the wealthy landowners because of their power and patronage. There was a time when industrial cities like the one fictionally represented by Coketown had no representation in Parliament at all.

I love the way Dickens personified Time (which surely should be capitalized in this context) and how it's almost become a character its own right in this chapter.

I love the way Dickens personified Time (which surely should be capitalized in this context) and how it's almost become a character its own right in this chapter. What are we to make of the sister that Rachael and Stephen refer to? Is this a literal reference? Is it Stephen's wife? Both? Here are the passages:

Rachael: Angels are not like me. Between them, and a working woman fu’ of faults, there is a deep gulf set. My little sister is among them, but she is changed.’

Stephen, later: And so I will try t’ look t’ th’ time, and so I will try t’ trust t’ th’ time, when thou and me at last shall walk together far awa’, beyond the deep gulf, in th’ country where thy little sister is.

I can't express how infuriated I am with Tom. You won’t forget how fond you are of me? AARGH!!!! Obviously he's not the least bit fond of poor Louisa. Selfish bastard. (Stepping back...breathing in...breathing out.... Okay, I'm better now.)

Peter -- great observation about the bottles. Let's see if they continue to pop up as the story continues.

Rachael as the angel.... I find myself liking her very much. She's self-sacrificing, but she's sober (both physically and temperamentally), and has been worn down by life and its disappointments. I can well imagine her going back to the privacy of her rooms, where she cries herself to sleep or screams into her pillow at the unfairness of it all. She's a God-fearing woman with a strong sense of duty, who tries to do what's right. She couldn't have lived with herself if she hadn't prevented Mrs. B's death, but if the unfortunate woman had died in her sleep, I don't think Rachael would have been so angelic as to not feel a huge sense of relief.

I don't know if it's the story itself, the fact that I'm reading it at a time when I need a good story that's a bit more straightforward, or the slow pace at which we're digesting it - maybe all three - but I'm really enjoying Hard Times.

Mary Lou wrote: "I can't express how infuriated I am with Tom. You won’t forget how fond you are of me? AARGH!!!! Obviously he's not the least bit fond of poor Louisa. Selfish bastard. (Stepping back...breathing in...breathing out.... Okay, I'm better now.)."

Mary Lou wrote: "I can't express how infuriated I am with Tom. You won’t forget how fond you are of me? AARGH!!!! Obviously he's not the least bit fond of poor Louisa. Selfish bastard. (Stepping back...breathing in...breathing out.... Okay, I'm better now.)."Hilarious. But whew -- I'm glad that you recovered!

I'm also finding this novel more engaging as the characters develop, including the addition of Stephen & Rachael. Chapter 13 really caught the feeling of that state between waking and dreaming, and for me, somewhat lets Stephen off the ethical hook for not acting when he sees his wife reach for the bottle -- he's not sure if it's a dream or reality. I'm also impressed by the depth of Stephen's & Rachael's faith, that they are sure they will be united in death, if not in life. Hell, for Stephen, is never looking on or hearing Rachael again. (He's also convinced of punishment.) A different context for viewing their dilemma.

I'm also finding this novel more engaging as the characters develop, including the addition of Stephen & Rachael. Chapter 13 really caught the feeling of that state between waking and dreaming, and for me, somewhat lets Stephen off the ethical hook for not acting when he sees his wife reach for the bottle -- he's not sure if it's a dream or reality. I'm also impressed by the depth of Stephen's & Rachael's faith, that they are sure they will be united in death, if not in life. Hell, for Stephen, is never looking on or hearing Rachael again. (He's also convinced of punishment.) A different context for viewing their dilemma.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."I took it to be some sort of disinfectant perhaps?"

Yes, since Rachael soaks the linen in it, I also thought it was an antiseptic for Mrs. Blackpool's wound.

Perhaps it's the influence of the commentators in the previous thread -- but I assumed the other bottle was opium.

Mary Lou wrote: "What are we to make of the sister that Rachael and Stephen refer to? Is this a literal reference? Is it Stephen's wife? Both?..."

Mary Lou wrote: "What are we to make of the sister that Rachael and Stephen refer to? Is this a literal reference? Is it Stephen's wife? Both?..."My edition has an endnote for Stephen's reply -- a long passage of dialogue in Dickens' manuscript that was not published, beginning, "Thou'st spoken o'thy little sister ... with her child arm tore off afore thy face!" So he apparently intended it literally, and as an opportunity to expose working conditions for factory children, and the inaction of government response. He also referenced an article in Household Words, 'Ground in the mill'.

Vanessa wrote: "My edition has an endnote for Stephen's reply -- ..."

Vanessa wrote: "My edition has an endnote for Stephen's reply -- ..."Thanks, Vanessa - that certainly adds some context! Some shoddy editing, keeping the other references in after deleting that passage. What a horrible image!

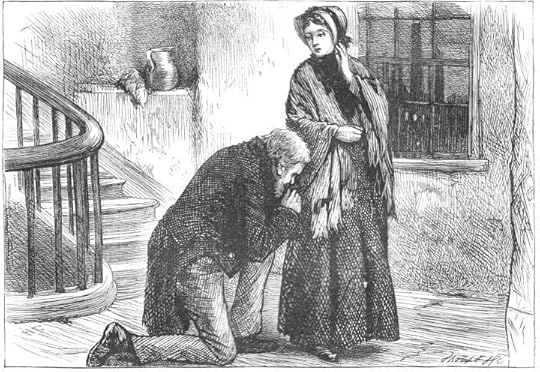

Finally we get to an illustration by Fred Walker, the first person to illustrate Hard Times.

Finally we get to an illustration by Fred Walker, the first person to illustrate Hard Times. "Other artists after Dickens's death would attempt to provide satisfactory illustrations for one of the few Dickens novels never attempted by his classic illustrators (Hablot Knight Browne, John Leech, and George Cruikshank), notably Charles S. Reinhart for the American and Harry French for the British Household Edition (both in the 1870s). However, the only artist to work on plates for the novel during Dickens's lifetime was the celebrated painter and magazine-illustrator Fred Walker. For the 1868 Library Edition of Dickens's works, Walker contributed four drawings to accompany Reprinted Pieces and a further four to accompany Hard Times all signed with the initials "F. W.".

Here is the first:

"Stephen and Rachel in the sick-room"

Chapter 13

Fred Walker

Commentary:

"In his initial scene within the pages of the text, "Stephen and Rachel in the Sick-room," Walker focuses upon the romantic triangle of the subplot. As Stephen watches, stupefied, from the foreground (from the viewer's perspective, so to speak) and Rachel momentarily doses beside the bed, the dipsomaniac's (whatever that is) right hand stealthily reaches for the larger of the two bottles on the small table (repeating the table of the first plate) while her left grasps a mug. The working-class sick-room is depicted in stark contrast to the affluent factory-owner's dining-room, a corner of which appears in the first plate. Here, bare floorboards protrude from beneath the ragged-edged carpet. Standing on a small (possibly three-legged) table without a cloth at the bedside a single candle illuminates the humble cell, unadorned except for an indeterminate picture in the rear. Whereas Dickens tells us that "A candle faintly burned in the window" at the very opening of Ch. 13, Book One, here it blazes with sacramental intensity, creating a haloed effect by its reflection on the wall above Rachel's head. There is no basin, but in her hands Rachel holds the linen strip mentioned in the letter-press. We see neither the trimmed fire nor the swept hearth, extensions of Rachel' s benign influence and tidy mindedness, but all is in good order. Rachel sits immediately by the bed, ready to minister to Mrs. Blackpool, as in the text screened by a curtain; this latter object, shown as part of a foreshortened canopy above the bed, Walker uses to tantalize and engage the viewer.

The precise moment captured is cued by the two bottles on the table, the strip of linen that the sleeping Rachel clutches, the moving hand. At the top of the page, Stephen rouses himself; at the bottom, Rachel has fallen into a dose, "wrapped in her shawl, perfectly still." Stephen notices the curtain slightly move as, on the page following, the hand steals forward. We have yet to see the creature in the bed and, held in suspense since the larger bottle for which she seems to be reaching contains poison, we visualize her from the clues Dickens has already provided: she is not in her right mind, is wounded in the neck, and bruised. We see her in our mind' s eye, but each of us completes her face and form differently, according to our individual conceptions of and experiences with the Fallen Woman.

Although Dickens develops the scene through Stephen's consciousness, here he seems a mere cipher; enclosed in darkness in Walker's plate, "as if a spell were on him, . . . motionless and powerless," Stephen's face and expression are revealed only in the accompanying letter-press. The picture's focal points are the dark bottle, the surreptitious hand, and the tranquil, mature beauty of Rachel's face, so like Louisa's in the former plate, despite their differences in class, education, and wealth. Walker leaves the defining of Mrs. Blackpool's image, softened by neither Christian name nor pet-name in the text, to the author himself, as the text describes the "haggard" aspect, the "woeful eyes," the "debauched features," all evidence of "brutish instinct." The woman's "greedy hand" that has in the past sold out and betrayed the marriage vow for drug-money now stretches forth--but this time its owner is aware of the bottle and grasps "a mug." Thus, Walker has heightened the suspense in this chapter by conflating two moments (two reachings) into one."

I also see no reason to keep poison on a table next to the bed.

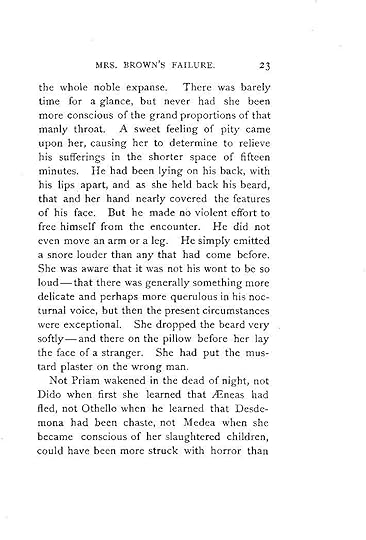

Now we are back to Harry French, his illustration of Chapter 13:

Now we are back to Harry French, his illustration of Chapter 13:

"He Went Down Upon His Knee Before Her On The Poor Mean Stairs, And Put An End Of Her Shawl To His Lips"

Chapter 13

Harry French

Text Illustrated:

"She looked at him, on his knee at her feet, with her shawl still in his hand, and the reproof on her lips died away when she saw the working of his face.

‘I coom home desp’rate. I coom home wi’out a hope, and mad wi’ thinking that when I said a word o’ complaint I was reckoned a unreasonable Hand. I told thee I had had a fright. It were the Poison-bottle on table. I never hurt a livin’ creetur; but happenin’ so suddenly upon ’t, I thowt, “How can I say what I might ha’ done to myseln, or her, or both!”’

She put her two hands on his mouth, with a face of terror, to stop him from saying more. He caught them in his unoccupied hand, and holding them, and still clasping the border of her shawl, said hurriedly:

‘But I see thee, Rachael, setten by the bed. I ha’ seen thee, aw this night. In my troublous sleep I ha’ known thee still to be there. Evermore I will see thee there. I nevermore will see her or think o’ her, but thou shalt be beside her. I nevermore will see or think o’ anything that angers me, but thou, so much better than me, shalt be by th’ side on’t. And so I will try t’ look t’ th’ time, and so I will try t’ trust t’ th’ time, when thou and me at last shall walk together far awa’, beyond the deep gulf, in th’ country where thy little sister is.’

He kissed the border of her shawl again, and let her go. She bade him good night in a broken voice, and went out into the street."

This illustration for the British Household Edition of Dickens's Hard Times.

Here is an illustration by C.S. Reinhart for Chapter 13:

Here is an illustration by C.S. Reinhart for Chapter 13:

"The Creature Struggled, Struck Her, Seized Her by the Hair; But Rachael Had the Cup."

Chapter 13

C. S. Reinhart

This plate illustrates Book One, Chapter Thirteen, "Rachael," in Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1870.

Commentary:

"We see not merely the same room from a different perspective, but the same woman in a wholly different mood, a hideous creature out of nightmare, her "debauched" face a terrifying spectre's or a witch's. Rachael, not even momentarily perturbed or set off balance by the unexpected assault, resolutely holds the cup (which moments before had contained the poisonous dram) in her right hand and grapples her attacker with her upstage (left) hand. This whole scene plays out in both media at once, for it begins at the top of the page and reaches the captioned moment at the bottom of the left-hand column.

The scene seems to be unfolding through the consciousness of Mrs. Blackpool as she stretches out her hand towards the bottle (in Reinhart's realization there is just one). However, since the running head above this illustration is "Stephen's Dream," Reinhart has developed the scene not from his usual perspective, that of an audience looking into the room through the fourth wall, but rather than of Stephen himself, seated across the room, looking towards the bed and the three-legged table at the bedside. As in the letter-press, Rachael's chair is by the curtained bed and Mrs. Blackpool regards her rival for Stephen's affections (the situation symbolized by the three-legged table) with eyes both "large" and "haggard and wild." A candle burns brightly on the window-ledge, flaring like the violent mood which has upon a sudden seized the addict."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."I took it to be some sort of disinfectant perhaps?"

It was probably that - and a rather clumsy plot device ;-)

Peter wrote: "Gradgrind is now the Member of Parliament for Coketown. To the original readers this would signal how the rising industrial class was slowly assuming its place in Parliament that was, in the past, the sole preserve of the wealthy landowners because of their power and patronage. There was a time when industrial cities like the one fictionally represented by Coketown had no representation in Parliament at all. "

Peter wrote: "Gradgrind is now the Member of Parliament for Coketown. To the original readers this would signal how the rising industrial class was slowly assuming its place in Parliament that was, in the past, the sole preserve of the wealthy landowners because of their power and patronage. There was a time when industrial cities like the one fictionally represented by Coketown had no representation in Parliament at all. "Dickens is probably thinking of the Reform Act of 1832 here, which considered the changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, e.g. by getting rid of the "rotten boroughs" (i.e. removing seats from boroughs whose population had declined in the wake of urbanization) and by granting seats to cities that grew in the process of industrializiation.

Everyman wrote: "It's an interesting ethical question. Should one intervene to prevent an act which would under normal circumstances be a wrong but in the particular case would substantially increase human happiness? "

Everyman wrote: "It's an interesting ethical question. Should one intervene to prevent an act which would under normal circumstances be a wrong but in the particular case would substantially increase human happiness? "That is indeed a very tricky question, and although the road to utilitarian ethics may have many a stumbling block - in this case, it seems rather gross to just look on while somebody is about to poison himself -, Kant's ethics likewise leads into absurd situation. As Peter said, the early Dickens would probably not have bothered too much about a dilemma like this.

Mary Lou wrote: "I love the way Dickens personified Time (which surely should be capitalized in this context) and how it's almost become a character its own right in this chapter.

Mary Lou wrote: "I love the way Dickens personified Time (which surely should be capitalized in this context) and how it's almost become a character its own right in this chapter. What are we to make of the siste..."

Mary Lou,

I'm glad that I am not Tom, for otherwise I would be afraid of ever running into you by chance ;-) As to the little sister Rachael is referring to, I took this quite literally to be a sister of Rachael's who died young - a subtle hint of Dickens at child mortality, maybe? - and who is still not forgotten by Rachael.

Rachael as a literary character does not intrigue me very much although, of course, I would definitely like and respect her in real life. As a reader of novels, however, I am more fascinated by more ambiguous characters - or even downright villainnesses (does this word exist?) like Becky Sharp. In HT, I find Louisa more interesting than Rachael because in Louisa, there is a spark of rebellion - I am referring to that oblique look of hers that has been mentioned twice or thrice - and maybe there will be development in her. I cannot figure of there being any development in Rachael just now.

Vanessa wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "What are we to make of the sister that Rachael and Stephen refer to? Is this a literal reference? Is it Stephen's wife? Both?..."

Vanessa wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "What are we to make of the sister that Rachael and Stephen refer to? Is this a literal reference? Is it Stephen's wife? Both?..."My edition has an endnote for Stephen's reply -- ..."

I had not read this when writing my previous post, but that seems to solve the Little Sister Mystery. Maybe the passage was deleted because the torn-off arm of a young girl might have been too much for Victorian readers.

Kim,

Kim,thanks again for the illustrations. The comments, esp. in the last case, made them a lot more conclusive to me. For example, at first I thought the way the artist presented Rachael rather clumsy in that her posture did not betray any surprise or inclination to give in to Mrs. Blackpool's attack. It simply did not come over as natural - but with the commentary, I can see the artist's point. I like, however, Fred Walker's generosity in dealing with Mrs. Blackpool, who is - indeed - denied a Christian name, by not exposing her haggard looks to the reader but benevolently drawing a curtain over them. And yet the curtain may all too soon become a pall ...

Tristram wrote: "Kim,

Tristram wrote: "Kim,thanks again for the illustrations. The comments, esp. in the last case, made them a lot more conclusive to me. For example, at first I thought the way the artist presented Rachael rather clu..."

Tristram

Good catch.

I never thought about it, but you are right. Mrs. Blackpool is not given a Christian name. When we consider how the last names certainly accurately portray character types, as the first names do, it is indeed a curiosity.

And a nod of thanks to you too Kim. As always, the illustrations enhance our reading. Walker, French and Reinhart all are powerful. I enjoy the commentary analysis as well. The comments of the candles I found insightful.

Vanessa wrote: "Yes, since Rachael soaks the linen in it, I also thought it was an antiseptic for Mrs. Blackpool's wound. ."

Vanessa wrote: "Yes, since Rachael soaks the linen in it, I also thought it was an antiseptic for Mrs. Blackpool's wound. ."they were a lot more casual about poisons back then. And about opiates.

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed.."I took it to be some sort of disinfectant perhaps?"

It was probably that - and a rather clumsy plot device ;-) ."

Why clumsy? At that time, they were much more casual about drugs including poisons. If Rachel were using it to disinfect her linens, why wouldn't it be there? No running water in the house, so presumably disinfected in a basin in the room; where else would it be but there close to hand? Not like modern homes where the laundry would be done elsewhere, or where you wouldn't be allowed a bottle of poison for disinfectant. I think it's not clumsy at all, but just a recognition of the normal process of a sickroom in a very small set of working class rooms in a crowded city.

Everyman wrote: "Why clumsy? At that time, they were much more casual about drugs including poisons."

Everyman wrote: "Why clumsy? At that time, they were much more casual about drugs including poisons."I'm wondering if you know so much about what happened way, way, way, way back then because you were there.

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "My edition has an endnote for Stephen's reply -- ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "My edition has an endnote for Stephen's reply -- ..."Thanks, Vanessa - that certainly adds some context! Some shoddy editing, keeping the other references in after deleting that p..."

You're welcome, Mary Lou. Yes, it leaves a lot unanswered, but maybe he'll work that grisly detail in later.

Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration by C.S. Reinhart for Chapter 13:

Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration by C.S. Reinhart for Chapter 13:Mrs. Blackpool regards her rival for Stephen's affections (the situation symbolized by the three-legged table) ..."

Thanks for the illustrations, Kim. I prefer Walker, but this bit of commentary made me laugh. This has to be meant ironically. He doesn't have any affection left for his wife --he wants, at least unconsciously, to kill her!

Another interesting endnote, for the description of Thomas in Chap 14: "Time… exercised [Thomas] diligently in his calculations relative to number one." Apparently this is a reference to "looking after his own interests, according to the central belief of Utilitarianism that human behaviour is motivated by self interest." I find this, too, ironic, since it only really applies to men/boys. Throughout the novel so far, Louisa has put her brother's interests before her own -- she takes the blame for the circus peeping, her grievance against her upbringing is that she can't entertain or cheer her brother, she seems to have little resentment that he is using her to make his life better, etc. I'm curious to know what she feels about her own future, staring in the fire…

Another interesting endnote, for the description of Thomas in Chap 14: "Time… exercised [Thomas] diligently in his calculations relative to number one." Apparently this is a reference to "looking after his own interests, according to the central belief of Utilitarianism that human behaviour is motivated by self interest." I find this, too, ironic, since it only really applies to men/boys. Throughout the novel so far, Louisa has put her brother's interests before her own -- she takes the blame for the circus peeping, her grievance against her upbringing is that she can't entertain or cheer her brother, she seems to have little resentment that he is using her to make his life better, etc. I'm curious to know what she feels about her own future, staring in the fire…

Yes indeed, Vanessa, self-centred? Louisa was not, at least where her brother was concerned. The ingrained notion that the male of the species took precedence may have eased her brother's journey through life; well, at least if Louisa had anything to do with it.

Yes indeed, Vanessa, self-centred? Louisa was not, at least where her brother was concerned. The ingrained notion that the male of the species took precedence may have eased her brother's journey through life; well, at least if Louisa had anything to do with it.On a side note, what's a bottle of poison between friends?! ;-). I hesitate to recount this little tale, but the lateness of the hour has fuddled my brain so this little story shall be brief:

It was a very hot day and my father had been gardening. He came inside. He was thirsty. He greedily drank lemonade as though there was no tomorrow; there might not have been. Yes, you're right. It was poison. To that effect it was coloured a very lurid, unmistakably bright, purple. My mother arrived on the scene and as all good wives would do, she hastily called the Emergency Services. No? No. She dissolved into an uncontrollable "fit of the giggles". THEN she phoned for help. (Where were the Gradgrinds and Bounderbys then, I should like to know? )

Peter wrote: "Being Valentine's Day, who could not love Rachael? I fully agree with Tristram that HT seems to have its chapters focus much more on a cause, an idea or a person than we have been used to in our ea..."

Peter wrote: "Being Valentine's Day, who could not love Rachael? I fully agree with Tristram that HT seems to have its chapters focus much more on a cause, an idea or a person than we have been used to in our ea..."Interesting point about the symbolism of the bottle. Let's see if any more appear down the track!

Everyman wrote: "they were a lot more casual about poisons back then."

Everyman wrote: "they were a lot more casual about poisons back then."In an age of lower life expectancy, what great risk did they run anyway? ;-)

Kim wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Why clumsy? At that time, they were much more casual about drugs including poisons."

Kim wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Why clumsy? At that time, they were much more casual about drugs including poisons."I'm wondering if you know so much about what happened way, way, way, way back then because you..."

Touché!

Everyman,

Everyman,I just read your post in the other thread - the one about the wife who had almost poisoned herself and two children. Apparently, they were really more casual about poisons back then, and after all in the Victorian age, opium was an ingredient of many kinds of medicine, and they would probably also have given some opium to children in order to make them sleep or to soothe pains. Taking this into consideration, I cannot maintain my opionion on the bottle being such a clumsy plot element.

Being casual about poison was still usual in my childhood: I well remember that my grandmother, when we children would not sleep well, would give us a draught containing egg liqueur as a household remedy. Today, whenever I see a bottle of egg liqueur, I have to think of my grandmother ;-)

Hilary wrote: "Yes indeed, Vanessa, self-centred? Louisa was not, at least where her brother was concerned. The ingrained notion that the male of the species took precedence may have eased her brother's journey t..."

Hilary wrote: "Yes indeed, Vanessa, self-centred? Louisa was not, at least where her brother was concerned. The ingrained notion that the male of the species took precedence may have eased her brother's journey t..."What a story, Hilary! Probably your mother started giggling as a means of coping with the stress of the situation.

Vanessa wrote: "Another interesting endnote, for the description of Thomas in Chap 14: "Time… exercised [Thomas] diligently in his calculations relative to number one." Apparently this is a reference to "looking a..."

Vanessa wrote: "Another interesting endnote, for the description of Thomas in Chap 14: "Time… exercised [Thomas] diligently in his calculations relative to number one." Apparently this is a reference to "looking a..."I was never quite sure what this phrase of "calculations relative to number one" was actually supposed to mean. So thanks for making this clear, Vanessa! I find it quite interesting that society was more lenient on self-centredness in men than in women. Even Dickens was not exempt from this: Why else would he glorify women like Rachael, Little Nell or Florence, who would always think of other people rather than of themselves?

Tristram wrote: "Being casual about poison was still usual in my childhood: I well remember that my grandmother, when we children would not sleep well, would give us a draught containing egg liqueur as a household remedy. "

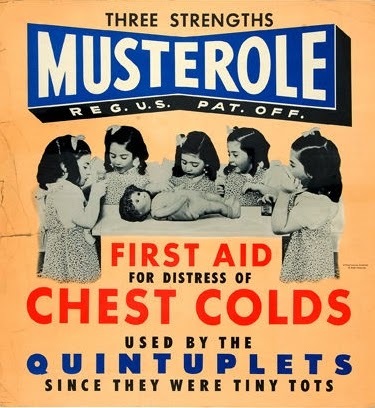

Tristram wrote: "Being casual about poison was still usual in my childhood: I well remember that my grandmother, when we children would not sleep well, would give us a draught containing egg liqueur as a household remedy. "The cough syrup given to my sister and me was on the order of 80 proof alcohol. And, of course, not knowing better, we were given aspirin regularly. And, of course, Musterole, which smelled awful and burned our skin, but worked.

Ah, egg liqueur and Musterole, I had to look both of them up, never heard of either one.

Ah, egg liqueur and Musterole, I had to look both of them up, never heard of either one."Egg liqueur, called Eierlikör in Germany and Advocaat in the Netherlands, is a traditional Dutch alcoholic beverage made from eggs, sugar and brandy. The rich and creamy drink has a smooth, custard-like flavor and is similar to eggnog. The typical alcohol content is generally somewhere between 14% and 20% ABV. Its contents may be a blend of egg yolks, aromatic spirits, sugar or honey, brandy, vanilla and sometimes cream (or evaporated milk). Notable makers of advocaat include Bols, DeKuyper and Verpoorten.

Advocaat is the Dutch word for "lawyer". As the name of the drink, it is short for advocatenborrel, or "lawyer's drink", where borrel is Dutch for a shot of an alcoholic beverage. According to the 1882 edition of the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche taal (Dictionary of the Dutch Language), it is "zoo genoemd als een goed smeersel voor de keel, en dus bijzonder dienstig geacht voor een advocaat, die in 't openbaar het woord moet voeren" ("so named as a good lubricant for the throat, and thus considered especially useful for a lawyer, who must speak in public.

Thick advocaat is sold mainly on the Dutch and Belgian market, though in lesser quantities it can also be found in German and Austrian markets. It is often eaten with a little spoon, while a more liquid version is sold as an export. Thick advocaat contains egg yolks, and is used as a waffle or poffertjes topping and as an ingredient for several kinds of desserts such as ice cream, custards and pastries. It is also served as an apéritif or digestif in a wide glass with whipped cream and cocoa powder sprinkled on top.

In the export variety whole eggs are used. The best known cocktail using advocaat is the Snowball: a mixture of advocaat, sparkling lemonade and sometimes lime juice, (although this is not required for the drink) that is often consumed near Christmas. Another is the Fluffy duck, made with rum. A highly popular advocaat-based beverage is the Bombardino, a drink commonly found in Italian ski resorts, particularly the Italian Alps, made by mixing advocaat, brandy, and whipped cream."

And then there is:

"Musterole was a medicinal rub that was used similar to Vicks VapoRub but can also be used similar to Ben Gay and other muscle and joint pain rubs. Musterole was first introduced in 1905, and the company was incorporated in 1907. The name comes from mustard, one of the principle ingredients.

Musterole's mechanism of action was as a counter-irritant. Counter-irritants are agents such as methyl salcylate, camphor, or menthol that actually cause irritation to the skin, but in so doing provide some relief of muscle or joint pain by dilating the blood vessels in the area and increasing blood flow, leading to a feeling of warmth. This provides a sort of masking effect for pain. All the mechanisms by which the agents work are not known, but they have been used for many years. Mustard is an irritant and in the right dose can work as a counter-irritant. A mustard-poultice laid on the chest is a time-honored remedy for cold and cough symptoms, helping to relieve chest congestion. Musterole was basically a pre-made mustard preparation, but it also contained other counter-irritant agents.

Musterole was known to be a mixture of mustard oil, menthol, and camphor in a base of lard or some similar fat. Applied to the skin in this way, pure mustard oil is much stronger than a simple mustard poultice, and when mixed with a fat such a lard, it may not only blister the skin, but cause a serious external reaction that spreads beyond the point of application. Not only this, but systemic reactions might occur, either through inhalation or absorption through the skin.

Indeed "A Case of Poisoning by Musterole" was described in the Journal of the American Medical Association by Dr. David I. Macht, of Baltimore, in 1917. It is unknown if the patient was simply allergic to the active ingredients, or the preparation was too strong. Most likely, it was some combination of the two. One thing that might happen if mustard oil is used injudiciously, is blistering of the skin. Cartons of Musterole in the early 1900's guaranteed that Musterole "Will Not Blister." Musterole claimed in ads that the salve "does the work of an old-fashioned mustard plaster, without the blister." This is curious since mustard oil is just as likely, if not more likely, to blister, than a plaster of mustard, depending on the concentration used. Once a mustard plaster is removed, the residue can be more easily washed off. The Musterole Company of Cleveland, Ohio also claimed Musterole was: Guaranteed under the Pure Food and Drugs Act June 30, 1906..For coughs and colds in the chest, pneumonia, asthma, bronchitis, croup, rheumatism, pleurisy, headache, neuralgia, sore joints, and muscles."

They both sound awful.

Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?

Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?

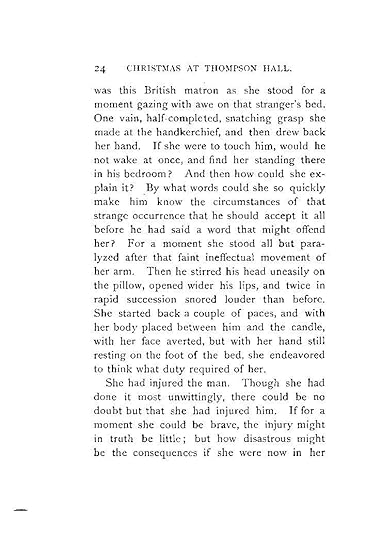

I'm trying hard to remember which book it was in which a female character snuck into the room of a man she thought she knew and applied a mustard poultice to the chest, only suddenly to find out that it was a complete stranger, and she crept out of his room in huge embarrassment and didn't go and take it off and in the morning his chest was horribly blistered.

I'm trying hard to remember which book it was in which a female character snuck into the room of a man she thought she knew and applied a mustard poultice to the chest, only suddenly to find out that it was a complete stranger, and she crept out of his room in huge embarrassment and didn't go and take it off and in the morning his chest was horribly blistered.

Everyman wrote: "Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?"

Everyman wrote: "Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?"Undoubtedly, the Dionne quintuplets who were, indeed, quite famous.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/fts/...

Everyman wrote: "Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?"

Everyman wrote: "Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?"Yes. Canadian, of course. Thanks Mary Lou for the details. They are still quite famous and remembered here in Canada. Geeez, I thought everyone knew about the Dionne quintuplets. :-))

You owe me a present for finding this one, either a Christmas house or a caroler. The name of the story is "Christmas at Thompson Hall" by Anthony Trollope, one of my favorite authors, but I never heard of the story before.

You owe me a present for finding this one, either a Christmas house or a caroler. The name of the story is "Christmas at Thompson Hall" by Anthony Trollope, one of my favorite authors, but I never heard of the story before.

Here's the rest of it. https://archive.org/stream/christmasa...

Kim wrote: "You owe me a present for finding this one, either a Christmas house or a caroler. The name of the story is "Christmas at Thompson Hall" by Anthony Trollope, one of my favorite authors, but I never ..."

Kim wrote: "You owe me a present for finding this one, either a Christmas house or a caroler. The name of the story is "Christmas at Thompson Hall" by Anthony Trollope, one of my favorite authors, but I never ..."Correct! One of the other GR groups read it as part of this past Christmas's readings (instead of the stories by that other guy, Dick somebody).

I do owe you. I'll do my best to find you a figure of Scrooge at his Scroogiest to populate your villages.

Peter wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?"

Peter wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Which all raises the question, who were the quintuplets? Were they a famous birth which people would know who they were at the time just from this ad?"Yes. Canadian, of course. T..."

I may have heard of them growing up, but if so I have no memory of them.

But that story that Mary Lou linked to is one of the saddest I have read in a long time. I doubt even Dickens in his most depressing moments could have written a story this tragic. Talk about exploitation by those who were most obligated to care for them, their parents and then the Provincial government of Ontario.

They may have become "a symbol of joy," but there seems to have been little joy for them.

Hi Kim! I need to get another device to

Hi Kim! I need to get another device tosee your illustrations. I'm sure that they're as fascinating as usual. You have taught me to

pay proper attention to illustrations, for the first time in my life! Thank you.

Tristram, you may find the sainted Rachael a bit of a 'fidget-inducer', a 'yawn' and a bore, but "Picture it" (all rights reserved by Sophia in 'The Golden Girls' and all the big guys who are under the delusion that they own it ;-)) :You're stupendously ill in bed. No orifice is sacred. Who will help me? I feel as though I might die! Who will see me safely on the road to life or, heaven forbid, death. Will it be Mrs Sparsit, Mrs Blackpool (freshly recovered) or Rachael? "You pays your money you takes your choice" (a catchphrase from many years ago) or "Will you take the money or open the box?" (From a game show in years gone by). The clock is ticking, Tristram!

On a side note, I wonder if Mrs Blackpool was called so because either she, at one time, perceived herself to be too 'grand' for her first name to be known or used in public. When I was growing up I knew a lady who was only ever known as Mrs 'X'. Many years later we found out that she had been living as a common law wife. It was no wonder then that she chose to emphasise her marital status, especially at a time when such a way of life was openly frowned upon.

Concerning the bottle, that blessed bottle. (Well, it was unlikely to have been Holy Water from Lourdes or the River Jordan). As you suggest, Everyman, that, in bygone days, there was more of a laissez faire attitude towards medicines, whether they be mild, medium or otherwise.

Here's a little story that may highlight this: a very good friend of ours had a baby in the early part of the 1940s. He cried and he cried and he cried and then he cried some more. What was she to do? Well, the obvious thing of course. She grabbed a bottle of Laudanum off the shelf. She got a dignified fit-for-purpose spoon from the drawer and proceeded to ladle it into the baby's mouth. Not a few spoonfuls later, said baby slept and he slept and he slept and then he slept some more; a full two days in

fact.

Oh so sorry, Everyman, it looks as though I've stolen something along the lines of your 'poison' anecdote, or to use Wodehouse's phrase 'stealing your nifties'. Neither your comment nor Kim's had appeared. Please excuse!!

Oh so sorry, Everyman, it looks as though I've stolen something along the lines of your 'poison' anecdote, or to use Wodehouse's phrase 'stealing your nifties'. Neither your comment nor Kim's had appeared. Please excuse!!

Hilary wrote: "On a side note, I wonder if Mrs Blackpool was called so because either she, at one time, perceived herself to be too 'grand' for her first name to be known or used in public. "

Hilary wrote: "On a side note, I wonder if Mrs Blackpool was called so because either she, at one time, perceived herself to be too 'grand' for her first name to be known or used in public. "Has Dickens actually called her that, or just us? I think she's only been called Stephen's wife. My guess is that Dickens is not naming her intentionally, giving us less chance of seeing her as an important character who might garner any of our sympathy.

this week’s two chapters concentrate on two different plot lines in a novel that, to me, seems to have its difficulties in getting under way and shaking a leg at all. Up to now, Hard Times has been more a collection of opportunities for Dickens to present his criticism as to utilitarianism or the Divorce Law, but finally we are led up to certain conflicts. Chapter 13 has an umpromising enough title, “Rachael”, being named for one of the least intriguing characters that have cropped up by now – the angelic woman who seems to have made suffering and patience her badge of honour.

The first sentence is bleak enough and sets the mood accordingly – we are in Stephen-Blackpool-country:

”A candle faintly burned in the window, to which the black ladder had often been raised for the sliding away of all that was most precious in this world to a striving wife and a brood of hungry babies; and Stephen added to his other thoughts the stern reflection, that of all the casualties of this existence upon earth, not one was dealt out with so unequal a hand as Death.”

Stephen comes home after a long walk in the storm and the rain, and he finds Rachael tending his sick wife. Dickens captures Stephen’s mood admirably:

”She turned her head, and the light of her face shone in upon the midnight of his mind.”

Then the narrator goes on, showing the estrangement between Stephen and his wife by pointing out that Stephen does not really see his wife because of a curtain that has been drawn around the bed but that, of course, he knows she is there. Again, the narrator makes it clear that Stephen is more in tune with the person who cares for the sick woman than with the sick woman herself:

”She sat by the bed, watching and tending his wife. That is to say, he saw that some one lay there, and he knew too well it must be she; but Rachael’s hands had put a curtain up, so that she was screened from his eyes. Her disgraceful garments were removed, and some of Rachael’s were in the room. Everything was in its place and order as he had always kept it, the little fire was newly trimmed, and the hearth was freshly swept. It appeared to him that he saw all this in Rachael’s face, and looked at nothing besides. While looking at it, it was shut out from his view by the softened tears that filled his eyes; but not before he had seen how earnestly she looked at him, and how her own eyes were filled too.”

During the conversation that ensues between Stephen and Rachael, we get to know that she was called in by the landlady, and that she used to be friends with Stephen’s wife before he had come to marry her. Rachael also throws in some Christian spirit, true to her nature, when she talks about why she is sitting by the drunkard’s bed, and she entreats Stephen to find some sleep because he has to go to work the next day. So does she, but she stresses that watching by a sickbed for a night will not put her out really since she has already had a sound night’s sleep last night. When Stephen looks at Rachael, she seems like a saint to him, which makes her even more boring to me as a character:

”Seen across the dim candle with his moistened eyes, she looked as if she had a glory shining round her head.”

Now something interesting happens: Stephen falls asleep and has a nightmare in which he re-experiences his marriage again. Then there comes something which I had better give in the narrator’s own words:

”While the ceremony was performing, and while he recognized among the witnesses some whom he knew to be living, and many whom he knew to be dead, darkness came on, succeeded by the shining of a tremendous light. It broke from one line in the table of commandments at the altar, and illuminated the building with the words. They were sounded through the church, too, as if there were voices in the fiery letters. Upon this, the whole appearance before him and around him changed, and nothing was left as it had been, but himself and the clergyman. They stood in the daylight before a crowd so vast, that if all the people in the world could have been brought together into one space, they could not have looked, he thought, more numerous; and they all abhorred him, and there was not one pitying or friendly eye among the millions that were fastened on his face. He stood on a raised stage, under his own loom; and, looking up at the shape the loom took, and hearing the burial service distinctly read, he knew that he was there to suffer death. In an instant what he stood on fell below him, and he was gone.”

I am not sure whether I got the allusion correctly but it seems to me that the words being referred to were one of the Commandments, and probably the one that puts severe restrictions on killing. Why else should Stephen dream of his own execution in the course of events? He then wakes up and finds himself in a half-slumber: Rachael has also fallen asleep but his wife has woken up and she is driven towards one of the bottles on the bedside table. Probably she thinks that the bottle contains some alcohol but it really has poison in it. I don’t really know why anybody would have a bottle with most deadly poison in it next to a sick-bed, and it does not seem to be any medicine because it is quite clear to Stephen that any little drop of the liquid would put an end to his wife’s earthly existence. Maybe the only reason for the bottle being there is to enable the plot to develop in this direction. He sees his wife reach for the bottle and uncork it, and yet he does not lift a finger to prevent her. Suddenly, Rachael awakes and saves Mrs. Blackpool’s life, having to fend off the wild drunkard as she does it. Frankly speaking, I don’t really know what I shall think of Stephen now: On the one hand, his apathy seems quite natural in his position but on the other hand, did he not actually look on when his wife was about to kill herself by mistaking the poison for alcohol? He might not have actually killed her himself but his just looking on makes him guilty of murder, doesn’t it?