The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Unreasonable Men

PRESIDENTIAL SERIES

>

OPEN - SPOTLIGHT - PRESIDENTIAL SERIES - GLOSSARY - UNREASONABLE MEN ~ (Spoiler Thread)

The Muck Rake

The Muck Rake

McClure's (cover, January 1901) published many early muckraker articles

The term muckraker was used in the Progressive Era to characterize reform-minded American journalists who wrote largely for all popular magazines. The modern term is investigative journalism, and investigative journalists today are often informally called "muckrakers." They relied on their own reporting and often worked to expose social ills and corporate and political corruption. Muckraking magazines—notably McClure's of publisher S. S. McClure—took on corporate monopolies and crooked political machines while raising public awareness of chronic urban poverty, unsafe working conditions, and social issues like child labor.

The muckrakers are most commonly associated with the Progressive Era period of American history. The journalistic movement emerged in the United States after 1900 and continued to be influential until World War I, when the movement came to an end through a combination of advertising boycotts, dirty tricks and "patriotism."

Before World War I, the term "muckraker" was used to refer in a general sense to a writer who investigates and publishes truthful reports to perform an auditing or watchdog function. In contemporary use, the term describes either a journalist who writes in the adversarial or alternative tradition, or a non-journalist whose purpose in publication is to advocate reform and change. Investigative journalists view the muckrakers as early influences and a continuation of watchdog journalism.

The term is a reference to a character in John Bunyan's classic Pilgrim's Progress, "the Man with the Muck-rake" that rejected salvation to focus on filth. It became popular after President Theodore Roosevelt referred to the character in a 1906 speech; Roosevelt acknowledged that "the men with the muck rakes are often indispensable to the well being of society; but only if they know when to stop raking the muck..."

While a literature of reform had already appeared by the mid-19th century, the kind of reporting that would come to be called "muckraking" began to appear around 1900. By the 1900s, magazines such as Collier's Weekly, Munsey's Magazine and McClure's Magazine were already in wide circulation and read avidly by the growing middle class. The January 1903 issue of McClure's is considered to be the official beginning of muckraking journalism, although the muckrakers would get their label later. Ida M. Tarbell ("The History of Standard Oil"), Lincoln Steffens ("The Shame of Minneapolis") and Ray Stannard Baker ("The Right to Work"), simultaneously published famous works in that single issue. Claude H. Wetmore and Lincoln Steffens' previous article "Tweed Days in St. Louis", in McClure's October 1902 issue was called the first muckraking article.

(Source: Wikipedia)

More:

http://historyofjournalism.onmason.co...

http://www.todayinliterature.com/stor...

https://prezi.com/l_vbwen9ixq8/the-ma...

http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speec...

http://voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu/theo...

http://www.dictionary.com/browse/muck...

by Arthur Weinberg (no photo)

by Arthur Weinberg (no photo) by Judith Serrin (no photo)

by Judith Serrin (no photo) by Kathleen Brady (no photo)

by Kathleen Brady (no photo) by Ellen F. Fitzpatrick (no photo)

by Ellen F. Fitzpatrick (no photo) by Louis Filler (no photo)

by Louis Filler (no photo) by

by

Jessica Mitford

Jessica Mitford by

by

Jessica Mitford

Jessica Mitford

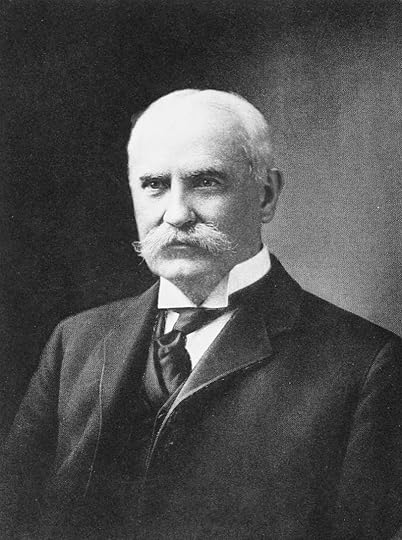

President William Howard Taft

President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was elected the 27th President of the United States (1909-1913) and later became the tenth Chief Justice of the United States (1921-1930), the only person to have served in both of these offices.

Distinguished jurist, effective administrator, but poor politician, William Howard Taft spent four uncomfortable years in the White House. Large, jovial, conscientious, he was caught in the intense battles between Progressives and conservatives, and got scant credit for the achievements of his administration.

Born in 1857, the son of a distinguished judge, he graduated from Yale, and returned to Cincinnati to study and practice law. He rose in politics through Republican judiciary appointments, through his own competence and availability, and because, as he once wrote facetiously, he always had his "plate the right side up when offices were falling."

But Taft much preferred law to politics. He was appointed a Federal circuit judge at 34. He aspired to be a member of the Supreme Court, but his wife, Helen Herron Taft, held other ambitions for him.

His route to the White House was via administrative posts. President McKinley sent him to the Philippines in 1900 as chief civil administrator. Sympathetic toward the Filipinos, he improved the economy, built roads and schools, and gave the people at least some participation in government.

President Roosevelt made him Secretary of War, and by 1907 had decided that Taft should be his successor. The Republican Convention nominated him the next year.

Taft disliked the campaign--"one of the most uncomfortable four months of my life." But he pledged his loyalty to the Roosevelt program, popular in the West, while his brother Charles reassured eastern Republicans. William Jennings Bryan, running on the Democratic ticket for a third time, complained that he was having to oppose two candidates, a western progressive Taft and an eastern conservative Taft.

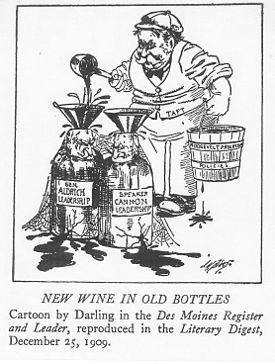

Progressives were pleased with Taft's election. "Roosevelt has cut enough hay," they said; "Taft is the man to put it into the barn." Conservatives were delighted to be rid of Roosevelt--the "mad messiah."

Taft recognized that his techniques would differ from those of his predecessor. Unlike Roosevelt, Taft did not believe in the stretching of Presidential powers. He once commented that Roosevelt "ought more often to have admitted the legal way of reaching the same ends."

Taft alienated many liberal Republicans who later formed the Progressive Party, by defending the Payne-Aldrich Act which unexpectedly continued high tariff rates. A trade agreement with Canada, which Taft pushed through Congress, would have pleased eastern advocates of a low tariff, but the Canadians rejected it. He further antagonized Progressives by upholding his Secretary of the Interior, accused of failing to carry out Roosevelt's conservation policies.

In the angry Progressive onslaught against him, little attention was paid to the fact that his administration initiated 80 antitrust suits and that Congress submitted to the states amendments for a Federal income tax and the direct election of Senators. A postal savings system was established, and the Interstate Commerce Commission was directed to set railroad rates.

In 1912, when the Republicans renominated Taft, Roosevelt bolted the party to lead the Progressives, thus guaranteeing the election of Woodrow Wilson.

Taft, free of the Presidency, served as Professor of Law at Yale until President Harding made him Chief Justice of the United States, a position he held until just before his death in 1930. To Taft, the appointment was his greatest honor; he wrote: "I don't remember that I ever was President."

(Source: The White House)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William...

http://www.history.com/topics/us-pres...

http://www.biography.com/people/willi...

http://millercenter.org/president/taft

http://blog.constitutioncenter.org/20...

http://www.americaslibrary.gov/jb/ref...

http://www.britannica.com/biography/W...

https://www.nps.gov/wiho/index.htm

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27547774...

(no image)The Life and Times of William Howard Taft: A Biography, Volume 2 by Henry F. Pringle (no photo)

(no image)The Foreign Policies Of The Taft Administration by Walter Vinton Scholes (no photo)

by Donald F. Anderson (no photo)

by Donald F. Anderson (no photo) by David Henry Burton (no photo)

by David Henry Burton (no photo) by Paolo E. Coletta (no photo)

by Paolo E. Coletta (no photo) by Paolo E. Coletta (no photo)

by Paolo E. Coletta (no photo)

Belle Case La Follette

Belle Case La Follette

Belle Case La Follette (April 21, 1859 – August 18, 1931) was a lawyer and a women's suffrage activist in Wisconsin, USA. La Follette worked with the women's peace party during World War I. At the time of her death in 1931, the New York Times called her "probably the least known yet most influential of all the American women who had to do with public affairs in this country".

She is best remembered as the wife and helpmate of Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette—a prominent Progressive Republican politician both in Wisconsin and on the national scene—and as co-editor with her husband of La Follette’s Weekly Magazine.

Belle Case was born on April 21, 1859 in Summit, Juneau County, Wisconsin. Her parents were Unitarian of English and Scottish descent. She attended the University of Wisconsin–Madison from 1875 to 1879 and, upon graduation, taught high school in Spring Green and junior high school in Baraboo. One of her students in Baraboo was John Ringling, of whom she later wrote "... when John read a long account -- interrupted with giggles from the school -- of the side shows he and other boys had been giving every night, I lectured him and drew the moral that if John would put his mind on his lessons as he did on side shows, he might yet become a scholar. Fortunately the scolding had no effect."

She married her former classmate at the University, Robert Marion La Follette Sr., on December 31, 1881. The ceremony was performed by a Unitarian minister and by mutual agreement, the word “obey” was omitted from the marriage vows. Their first child, Flora Dodge La Follette, always called “Fola”, was born on September 10, 1882. Fola married the playwright George Middleton on October 29, 1911.

Belle Case La Follette returned to the University of Wisconsin Law School and became the school’s first woman graduate in 1885. She never practiced as an attorney but she assisted her husband and he frequently acknowledged her authorship or contribution to a brief. She supported and assisted her husband as he rose through the political offices of Dane County District Attorney, United States Representative, Governor of Wisconsin, United States Senator, and Presidential candidate.

Her other children were Robert Jr., born in 1895, who succeeded his father as Senator; Philip, born in 1897, who became Governor of Wisconsin; and Mary, born in 1899. Her sons began the Wisconsin Progressive Party, which briefly held a dominant role in Wisconsin politics.

Belle lectured on women’s suffrage and other topics of the day. In 1909 she edited the “Home and Education” column in the magazine started by her husband, La Follette’s Weekly Magazine, which later became The Progressive. In 1911 and 1912 she wrote a syndicated column for the North American Press Syndicate. In 1914 Belle addressed the colored Young Men's Christian Association, raising an argument that segregation of colored people on street cars, public conveyances, and government departments was wrong. She added there would be no constitution of peace until the question is "settled right".

When suffragists made appearances at more than 70 county fairs in 1912, Belle Case visited seven of them in 10 days. In 1915 she helped found the Woman’s Peace Party, which later became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. After World War I, she was active in the Women’s Committee for World Disarmament, and helped found the National Council for the Prevention of War in 1921. She and other women influenced governments to convene the Naval Arms Limitation Conference in 1922.

After her husband’s death on June 18, 1925, his seat in the United States Senate was offered to her, but she turned down the opportunity to become the first woman Senator, perhaps because it would have upset the very balance between her public and private lives that she is esteemed for.

She died on August 18, 1931 in Washington D.C., as the result of a punctured intestine and peritonitis following a routine medical exam. She was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in Madison. (Source: Wikipedia)

More:

http://wimedialab.org/biographies/laf...

http://badgerbios.blogspot.hr/p/bell-...

http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Conte...

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAW...

http://womeninwisconsin.org/belle-cas...

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/suff...

https://news.google.com/newspapers?id...

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract...

by Lucy Freeman (no photo)

by Lucy Freeman (no photo) by Bernard A. Weisberger (no photo)

by Bernard A. Weisberger (no photo) by Nancy C. Unger (no photo)

by Nancy C. Unger (no photo) by Bob Kann (no photo)

by Bob Kann (no photo) by Greta Anderson (no photo)

by Greta Anderson (no photo)

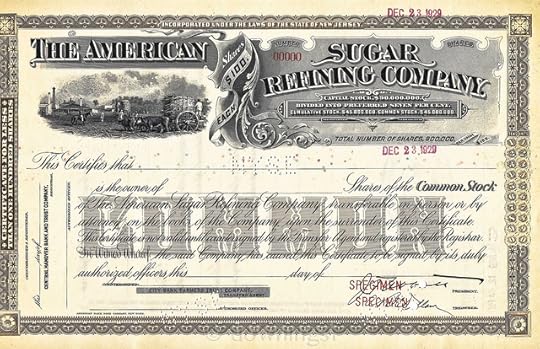

The Antitrust Laws

Congress passed the first antitrust law, the Sherman Act, in 1890 as a "comprehensive charter of economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as the rule of trade."

In 1914, Congress passed two additional antitrust laws: the Federal Trade Commission Act, which created the FTC, and the Clayton Act. With some revisions, these are the three core federal antitrust laws still in effect today.

The antitrust laws proscribe unlawful mergers and business practices in general terms, leaving courts to decide which ones are illegal based on the facts of each case. Courts have applied the antitrust laws to changing markets, from a time of horse and buggies to the present digital age. Yet for over 100 years, the antitrust laws have had the same basic objective: to protect the process of competition for the benefit of consumers, making sure there are strong incentives for businesses to operate efficiently, keep prices down, and keep quality up.

Here is an overview of the three core federal antitrust laws.

The Sherman Act outlaws "every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade," and any "monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy or combination to monopolize." Long ago, the Supreme Court decided that the Sherman Act does not prohibit every restraint of trade, only those that are unreasonable. For instance, in some sense, an agreement between two individuals to form a partnership restrains trade, but may not do so unreasonably, and thus may be lawful under the antitrust laws. On the other hand, certain acts are considered so harmful to competition that they are almost always illegal. These include plain arrangements among competing individuals or businesses to fix prices, divide markets, or rig bids. These acts are "per se" violations of the Sherman Act; in other words, no defense or justification is allowed.

The penalties for violating the Sherman Act can be severe. Although most enforcement actions are civil, the Sherman Act is also a criminal law, and individuals and businesses that violate it may be prosecuted by the Department of Justice. Criminal prosecutions are typically limited to intentional and clear violations such as when competitors fix prices or rig bids. The Sherman Act imposes criminal penalties of up to $100 million for a corporation and $1 million for an individual, along with up to 10 years in prison. Under federal law, the maximum fine may be increased to twice the amount the conspirators gained from the illegal acts or twice the money lost by the victims of the crime, if either of those amounts is over $100 million.

The Federal Trade Commission Act bans "unfair methods of competition" and "unfair or deceptive acts or practices." The Supreme Court has said that all violations of the Sherman Act also violate the FTC Act. Thus, although the FTC does not technically enforce the Sherman Act, it can bring cases under the FTC Act against the same kinds of activities that violate the Sherman Act. The FTC Act also reaches other practices that harm competition, but that may not fit neatly into categories of conduct formally prohibited by the Sherman Act. Only the FTC brings cases under the FTC Act.

The Clayton Act addresses specific practices that the Sherman Act does not clearly prohibit, such as mergers and interlocking directorates (that is, the same person making business decisions for competing companies). Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers and acquisitions where the effect "may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly." As amended by the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, the Clayton Act also bans certain discriminatory prices, services, and allowances in dealings between merchants. The Clayton Act was amended again in 1976 by the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act to require companies planning large mergers or acquisitions to notify the government of their plans in advance. The Clayton Act also authorizes private parties to sue for triple damages when they have been harmed by conduct that violates either the Sherman or Clayton Act and to obtain a court order prohibiting the anticompetitive practice in the future.

In addition to these federal statutes, most states have antitrust laws that are enforced by state attorneys general or private plaintiffs. Many of these statutes are based on the federal antitrust laws.

Source: Federal Trade Commission

Congress passed the first antitrust law, the Sherman Act, in 1890 as a "comprehensive charter of economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as the rule of trade."

In 1914, Congress passed two additional antitrust laws: the Federal Trade Commission Act, which created the FTC, and the Clayton Act. With some revisions, these are the three core federal antitrust laws still in effect today.

The antitrust laws proscribe unlawful mergers and business practices in general terms, leaving courts to decide which ones are illegal based on the facts of each case. Courts have applied the antitrust laws to changing markets, from a time of horse and buggies to the present digital age. Yet for over 100 years, the antitrust laws have had the same basic objective: to protect the process of competition for the benefit of consumers, making sure there are strong incentives for businesses to operate efficiently, keep prices down, and keep quality up.

Here is an overview of the three core federal antitrust laws.

The Sherman Act outlaws "every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade," and any "monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy or combination to monopolize." Long ago, the Supreme Court decided that the Sherman Act does not prohibit every restraint of trade, only those that are unreasonable. For instance, in some sense, an agreement between two individuals to form a partnership restrains trade, but may not do so unreasonably, and thus may be lawful under the antitrust laws. On the other hand, certain acts are considered so harmful to competition that they are almost always illegal. These include plain arrangements among competing individuals or businesses to fix prices, divide markets, or rig bids. These acts are "per se" violations of the Sherman Act; in other words, no defense or justification is allowed.

The penalties for violating the Sherman Act can be severe. Although most enforcement actions are civil, the Sherman Act is also a criminal law, and individuals and businesses that violate it may be prosecuted by the Department of Justice. Criminal prosecutions are typically limited to intentional and clear violations such as when competitors fix prices or rig bids. The Sherman Act imposes criminal penalties of up to $100 million for a corporation and $1 million for an individual, along with up to 10 years in prison. Under federal law, the maximum fine may be increased to twice the amount the conspirators gained from the illegal acts or twice the money lost by the victims of the crime, if either of those amounts is over $100 million.

The Federal Trade Commission Act bans "unfair methods of competition" and "unfair or deceptive acts or practices." The Supreme Court has said that all violations of the Sherman Act also violate the FTC Act. Thus, although the FTC does not technically enforce the Sherman Act, it can bring cases under the FTC Act against the same kinds of activities that violate the Sherman Act. The FTC Act also reaches other practices that harm competition, but that may not fit neatly into categories of conduct formally prohibited by the Sherman Act. Only the FTC brings cases under the FTC Act.

The Clayton Act addresses specific practices that the Sherman Act does not clearly prohibit, such as mergers and interlocking directorates (that is, the same person making business decisions for competing companies). Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers and acquisitions where the effect "may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly." As amended by the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, the Clayton Act also bans certain discriminatory prices, services, and allowances in dealings between merchants. The Clayton Act was amended again in 1976 by the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act to require companies planning large mergers or acquisitions to notify the government of their plans in advance. The Clayton Act also authorizes private parties to sue for triple damages when they have been harmed by conduct that violates either the Sherman or Clayton Act and to obtain a court order prohibiting the anticompetitive practice in the future.

In addition to these federal statutes, most states have antitrust laws that are enforced by state attorneys general or private plaintiffs. Many of these statutes are based on the federal antitrust laws.

Source: Federal Trade Commission

message 56:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 25, 2016 11:06PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherman...

https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?...

https://www.shrm.org/legalissues/fede...

http://www.linfo.org/sherman_txt.html

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h760...

On the Progressive Movement - http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h106...

On Muckrakers - http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h920...

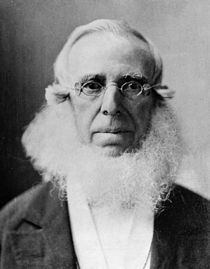

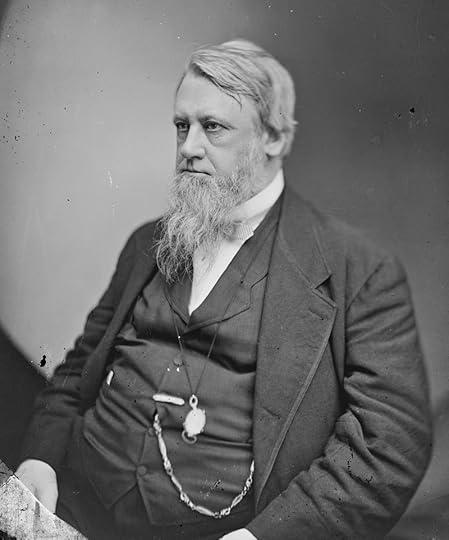

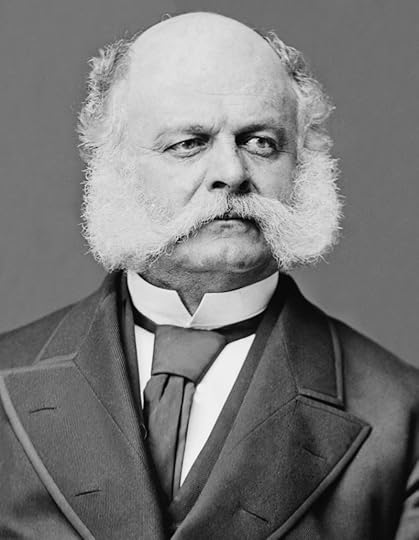

"Sen. John Sherman (R–OH), the principal author of the Sherman Antitrust Act."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherman...

https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?...

https://www.shrm.org/legalissues/fede...

http://www.linfo.org/sherman_txt.html

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h760...

On the Progressive Movement - http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h106...

On Muckrakers - http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h920...

"Sen. John Sherman (R–OH), the principal author of the Sherman Antitrust Act."

Benjamin Tillman

Benjamin Tillman

Benjamin Ryan Tillman (August 11, 1847 – July 3, 1918) was a politician of the Democratic Party who was Governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and a United States Senator from 1895 until his death in 1918. A white supremacist who often spoke out against blacks, Tillman led a paramilitary group of Red Shirts during South Carolina's violent 1876 election. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, he frequently ridiculed blacks, and boasted of having helped to kill them during that campaign.

In the 1880s, Tillman, a wealthy landowner, became dissatisfied with the Democratic leadership and led a movement of white farmers calling for reform. He was initially unsuccessful, though he was instrumental in the founding of Clemson University as an agricultural school. In 1890, Tillman took control of the state Democratic Party, and was elected governor. During his four years in office, 18 African Americans were lynched in South Carolina—the 1890s saw the most lynchings of any decade in South Carolina. Tillman tried to prevent lynchings, but spoke in support of the lynch mobs, stating his own willingness to lead one. In 1894, at the end of his second two-year term, he was elected to the U.S. Senate by vote of the state legislature.

Tillman was known as "Pitchfork Ben" because of his aggressive language, as when he threatened to use one to prod that "bag of beef", President Grover Cleveland. Considered a possible candidate for the Democratic nomination for president in 1896, Tillman lost any chance after giving a disastrous speech at the convention. He became known for his virulent oratory (especially against African Americans) but also as an effective legislator. The first federal campaign finance law, banning corporate contributions, is commonly called the Tillman Act. Tillman was repeatedly re-elected, serving in the Senate for the rest of his life. One of his legacies was South Carolina's 1895 constitution, which disenfranchised most of the black majority and ensured white rule for more than half a century.

From Britannica:

American Politician

Benjamin R. Tillman, byname Pitchfork Ben Tillman (born Aug. 11, 1847, Edgefield county, S.C., U.S.—died July 3, 1918, Washington, D.C.) outspoken U.S. populist politician who championed agrarian reform and white supremacy. Tillman served as governor of South Carolina (1890–94) and was a member of the U.S. Senate (1895–1918).

A farmer prior to his entry into politics, Tillman, a Democrat, emerged during the 1880s as a spokesman for poor rural whites in South Carolina in their conflict against both the ruling white aristocracy and the impoverished Negro population. The rise of Tillman marked the decline of the former Confederate general Wade Hampton as a political force in the state. Elected governor in 1890, Tillman translated his populist rhetoric into concrete reforms. He shifted the tax burden to the wealthy, improved public education, founded the agricultural college later to be known as Clemson University, and regulated the railroads. He also helped write the state constitution to disfranchise Negroes and circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment with a patchwork of Jim Crow laws (i.e., laws enforcing racial segregation). An unabashed bigot, he considered lynching an acceptable law-enforcement measure.

Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1894, Tillman served until his death, continuing to press for agrarian reform on the national level. He bitterly assailed Pres. Grover Cleveland for his hard-money policy, supporting instead the free-silver program of William Jennings Bryan. In most instances he opposed the administration of Pres. Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, the two became such bitter enemies that at one point the President barred Tillman from the White House. They put aside their differences long enough, however, to collaborate in securing passage of the Hepburn Act (1906), extending the Interstate Commerce Commission’s regulatory powers over the railroads. Tillman was floor leader for the bill. He generally supported Pres. Woodrow Wilson and, as chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, promoted the administration’s program to strengthen the Navy. His vituperative and often profane attacks on his political opponents earned him the nickname “Pitchfork Ben”; he once had a fistfight with his South Carolina colleague on the floor of the Senate.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjami...

http://www.britannica.com/biography/B...

message 58:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 26, 2016 12:25PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

OK - < b >text< / b > just take out the spaces and replace the word text with Benjamin Tillman

That is it for bolding

Clean up your spacing - you have too much spacing in some of the places and for your links - just say

Sources: and you can then here

That is it for bolding

Clean up your spacing - you have too much spacing in some of the places and for your links - just say

Sources: and you can then here

Bentley wrote: "OK - text just take out the spaces and replace the word text with Benjamin Tillman

Bentley wrote: "OK - text just take out the spaces and replace the word text with Benjamin TillmanThat is it for bolding

Clean up your spacing - you have too much spacing in some of the places and for your link..."

Got the bolding but not the image yet.

message 60:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 26, 2016 04:10PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

@ Helga

< img src="place the jpg file address here between the quotes and nothing else" / >

I ignore everything else about height and width - usually all jpeg and tiff files work

So take out all of the spaces aside from the one between img and src

See if we can get you to learn this.

< img src="place the jpg file address here between the quotes and nothing else" / >

I ignore everything else about height and width - usually all jpeg and tiff files work

So take out all of the spaces aside from the one between img and src

See if we can get you to learn this.

Bentley wrote: "@ Helga

Bentley wrote: "@ Helga I ignore everything else about height and width - usually all jpeg and tiff files work

So take out all of the spaces aside from the one between img and src

See if we can get you to le..."

Got it now. Thanks alot.

Charles Carroll

Charles Carroll

Charles Carroll was a Maryland delegate to the Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Born into a wealthy family, Charles Carroll became a member of the Continental Congress as the American Revolution loomed. Carroll missed the vote on independence but signed the final draft of the Declaration on Independence, becoming the only Catholic to do so. He was a member of the Maryland state Senate and the U.S. Senate (concurrently), finally retiring to private life in 1800.

Before his death in 1832, he was the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Early Years

Charles Carroll was born in September 1737 into a prominent Annapolis, Maryland, family. He was educated at Jesuit colleges in Maryland and France before going on to study law in Paris and London. In 1765 he returned to Maryland an educated man to take the reins of the family estate (which was one of the largest in the American colonies). He also added "of Carrollton" to his name (he appears as "Charles Carroll of Carrollton" in certain sources) to distinguish himself from his father and cousins, all of whom had similar names.

Because he was a Catholic, Carroll was not allowed to participate in politics, practice law (despite years of study) or vote, but he became known in important circles in a roundabout way by writing various anti-tax/tariff tracts (essentially, early protestations against "taxation without representation") in the Maryland Gazette under the pseudonym "First Citizen."

The War Looms

With the Revolution gearing up, in 1774 Carroll found himself approached by Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Chase to help gain the support of the Canadian government for their cause. Carried out by all three men, the eventual mission was not a success, but two years later Carroll was appointed to the Continental Congress, where he was an influential member of the Board of War and an early advocate for armed resistance and the ultimate severing of governmental ties with England. (He was nominated again in 1780 but decided not to accept the post.)

Postwar Activities

Although Carroll was not present to vote on the issue of independence, he was present for the signing of the final Declaration of Independence. Soon after, he resigned from the Continental Congress to serve in the Maryland State Assembly, where he was part of the group that drafted Maryland's constitution.

In 1777, Carroll became a Maryland state senator, serving until 1800. In 1789 he was elected U.S. senator, and he served as both a state and U.S. senator until 1793. In 1800 he retired from politics to concentrate on business matters: managing his vast real estate holdings, expanding his interests in the westward canal system and later helping to establish the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company.

Charles Carroll, the only Roman Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence, was also the last surviving signer, dying in Baltimore in 1832 at the age of 95. (Source: Biography.com)

More:

http://charlescarrollhouse.com

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles...

http://www.adherents.com/people/pc/Ch...

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03379...

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

https://youtu.be/oE8OuHsrYKg

(no image) Life of Charles Carroll of Carrollton by Lewis Leonard (no photo)

(no image) Charles Carroll of Carrollton by Thomas O'Brien Hanley (no photo)

(no image) Eulogy on Charles Carroll of Carrollton by John Sergeant (no photo)

(no image) Charles Carroll and the American Revolution by Milton Lomask (no photo)

(no image) Journal of Charles Carroll of Carrolton by Brantz Mayer (no photo)

by Scott McDermott (no photo)

by Scott McDermott (no photo) by Lewis Alexander 1845-1926 Leonard (no photo)

by Lewis Alexander 1845-1926 Leonard (no photo) by

by

Bradley J. Birzer

Bradley J. Birzer

Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791 – April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and candidate for President of the United States. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the Tom Thumb,[1] and founded the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in Manhattan, New York City.

Early life

Peter Cooper was born in New York City of Dutch, English and Huguenot descent, the fifth child of John Cooper, a Methodist hatmaker from Newburgh, New York. He worked as a coachmaker's apprentice, cabinet maker, hatmaker, brewer and grocer, and was throughout a tinkerer: he developed a cloth-shearing machine which he attempted to sell, as well as an endless chain he intended to be used to pull boats on the Erie Canal, which De Witt Clinton approved of, but which Cooper was unable to sell.

In 1821 Cooper purchased a glue factory on Sunfish Pond for $2,000 in Kips Bay, where he had access to raw materials from the nearby slaughterhouses, and ran it as a successful business for many years, producing a profit of $10,000 (equivalent to roughly $200,000 today) within 2 years, developing new ways to produce glues and cements, gelatin, isinglass and other products, and becoming the city's premier provider to tanners, manufacturers of paints, and dry-goods merchants. The effluent from his successful factory eventually polluted the pond to the extent that in 1839 it had to be drained and refilled.

Business career

Having been convinced that the proposed Baltimore and Ohio Railroad would drive up prices for land in Maryland, Cooper used his profits to buy 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land there in 1828 and began to develop them, draining swampland and flattening hills, during which he discovered iron ore on his property. Seeing the B&O as a natural market for iron rails to be made from his ore, he founded the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore, and when the railroad developed technical problems, he put together the Tom Thumb steam locomotive for them in 1830 from various old parts, including musket barrels, and some small-scale steam engines he had fiddled with back in New York. The engine was a rousing success, prompting investors to buy stock in B&O, which enabled the company to buy Cooper's iron rails, making him what would be his first fortune.

Cooper began operating an iron rolling mill in New York beginning in 1836, where he was the first to successfully use anthracite coal to puddle iron. Cooper later moved the mill to Trenton, New Jersey on the Delaware River to be closer to the sources of the raw materials the works needed. His son and son-in-law, Edward Cooper and Abram S. Hewitt, later expanded the Trenton facility into a giant complex employing 2,000 people, in which iron was taken from raw material to finished product.

Cooper also operated a successful glue factory in Gowanda, New York that produced glue for decades. A glue factory was originally started in association with the Gaensslen Tannery, there, in 1874, though the first construction of the glue factory's plant, originally owned by Richard Wilhelm and known as the Eastern Tanners Glue Company, began on May 5, 1904.[10] Gowanda, therefore, was known as America's glue capital.

Cooper owned a number of patents for his inventions, including some for the manufacture of gelatin, and he developed standards for its production. The patents were later sold to a cough syrup manufacturer who developed a pre-packaged form which his wife named "Jell-O".

Cooper later invested in real estate and insurance, and became one of the richest men in New York City. Despite this, he lived relatively simply in an age when the rich were indulging in more and more luxury. He dressed in simple, plain clothes, and limited his household to only two servants; when his wife bought an expensive and elaborate carriage, he returned it for a more sedate and cheaper one. Cooper remained in his home at Fourth Avenue and 28th Street even after the New York and Harlem Railroad established freight yards where cattle cars were parked practically outside his front door, although he did move to the more genteel Gramercy Park development in 1850.

In 1854, Cooper was one of five men who met at the house of Cyrus West Field in Gramercy Park to form the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company, and, in 1855, the American Telegraph Company, which bought up competitors and established extensive control over the expanding American network on the Atlantic Coast and in some Gulf coast states. He was among those supervising the laying of the first Transatlantic telegraph cable in 1858.

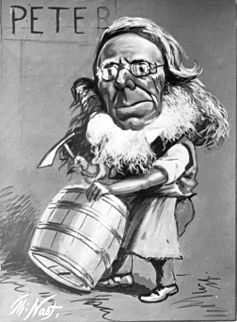

Cartoon of Peter Cooper by Thomas Nast

Political views and career

In 1840, Cooper became an alderman of New York City.

Prior to the Civil War, Cooper was active in the anti-slavery movement and promoted the application of Christian concepts to solve social injustice. He was a strong supporter of the Union cause during the war and an advocate of the government issue of paper money.

Influenced by the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Cooper became involved in the Indian reform movement, organizing the privately funded United States Indian Commission. This organization, whose members included William E. Dodge and Henry Ward Beecher, was dedicated to the protection and elevation of Native Americans in the United States and the elimination of warfare in the western territories.

Cooper's efforts led to the formation of the Board of Indian Commissioners, which oversaw Ulysses S. Grant's Peace Policy. Between 1870 and 1875, Cooper sponsored Indian delegations to Washington, D.C., New York City, and other Eastern cities. These delegations met with Indian rights advocates and addressed the public on United States Indian policy. Speakers included: Red Cloud, Little Raven, and Alfred B. Meacham and a delegation of Modoc and Klamath Indians.

Cooper was an ardent critic of the gold standard and the debt-based monetary system of bank currency. Throughout the depression from 1873–78, he said that usury was the foremost political problem of the day. He strongly advocated a credit-based, Government-issued currency of United States Notes. In 1883 his addresses, letters and articles on public affairs were compiled into a book, Ideas for a Science of Good Government.

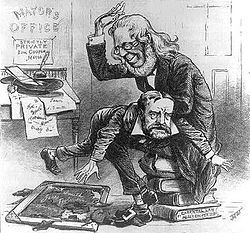

1879 Puck cartoon shows Cooper spanking his son Mayor Edward Cooper

Presidential candidacy

Cooper was encouraged to run in the 1876 presidential election for the Greenback Party without any hope of being elected. His running mate was Samuel Fenton Cary. The campaign cost more than $25,000. At the age of 85 years, Cooper is the oldest person ever nominated by any political party for President of the United States. The election was won by Rutherford Birchard Hayes of the Republican Party. Cooper was surpassed by another unsuccessful candidate: Samuel Jones Tilden of the Democratic Party.

Death and legacy

Cooper died on April 4, 1883 at the age of 92 and is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Aside from Cooper Union, the Peter Cooper Village apartment complex in Manhattan; the Peter Cooper Elementary School in Ringwood, New Jersey; the Peter Cooper Station post office; and Cooper Square in Manhattan are named in his honor. (Source: Wikipedia)

More:

https://www.cooper.edu/about/history/...

http://www.ringwoodmanor.com/peo/ch/p...

http://www.biography.com/people/peter...

http://www.britannica.com/biography/P...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuyves...

(no image) Life and Character of Peter Cooper by Charles Edwards Lester (no photo)

by Peter Cooper (no photo)

by Peter Cooper (no photo) by Rossiter Worthington Raymond (no photo)

by Rossiter Worthington Raymond (no photo) by Polly Guerin (no photo)

by Polly Guerin (no photo) by Ross Thomson (no photo)

by Ross Thomson (no photo) by Peter Cooper (no photo)

by Peter Cooper (no photo)

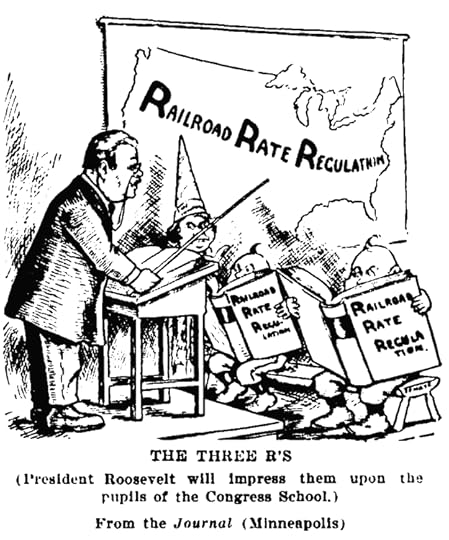

Hepburn Act

Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that gave the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) the power to set maximum railroad rates and extend its jurisdiction. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. In addition, the ICC could view the railroads' financial records, a task simplified by standardized bookkeeping systems. For any railroad that resisted, the ICC's conditions would remain in effect until the outcome of legislation said otherwise. By the Hepburn Act, the ICC's authority was extended to cover bridges, terminals, ferries, railroad sleeping cars, express companies and oil pipelines.

Along with the Elkins Act of 1903, the Hepburn Act, named for its sponsor, eleven-term Republican William Peters Hepburn, was a subset of one of President Theodore Roosevelt's major goals: railroad regulation.

The final version was close to what Roosevelt had asked, and easily passed Congress with only three dissenting votes. The most important provision gave the ICC the power to replace existing rates with "just-and-reasonable" maximum rates, with the ICC to define what was just and reasonable. The Act made ICC orders binding; that is, the railroads had to either obey or contest the ICC orders in federal court. To speed the process, appeals from the district courts would go directly to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Anti-rebate provisions were toughened, free passes were outlawed, and the penalties for violation were increased. The ICC staff grew from 104 in 1890 to 178 in 1905, 330 in 1907, and 527 in 1909. Finally, the ICC gained the power to prescribe a uniform system of accounting, require standardized reports, and inspect railroad accounts.

The limitation on railroad rates depreciated the value of railroad securities, a factor in causing the Panic of 1907.

Scholars consider the Hepburn Act the most important piece of legislation regarding railroads in the first half of the 20th century. Economists and historians debate whether it crippled the railroads, giving so much advantage to the shippers that a giant unregulated trucking industry—undreamed of in 1906—took away their business. (Source: Wikipedia)

More:

https://www.archives.gov/legislative/...

http://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.or...

https://dwkcommentaries.com/2014/08/2...

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h921...

http://commercial.laws.com/hepburn-act

http://study.com/academy/lesson/the-h...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Hep...

(no image)Enterprise Denied: Origins of the Decline of American Railroads, 1897-1917 by Albro Martin (no photo)

(no image)Railroads in the Age of Regulation, 1900-1980 by Keith L. Bryant Jr. (no photo)

by Richard D. Stone (no photo)

by Richard D. Stone (no photo) by John J. Cooper (no photo)

by John J. Cooper (no photo) by Marc Allen Eisner (no photo)

by Marc Allen Eisner (no photo) by Gabriel Kolko (no photo)

by Gabriel Kolko (no photo) by

by

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

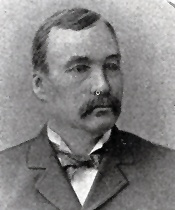

William Peters Hepburn

William Peters Hepburn

William Peters Hepburn (November 4, 1833 – February 7, 1916)–lawyer and U.S. representative—was born in Wellsville, Ohio. His father, John S. Hepburn, a West Point-educated artillery officer, died in New Orleans of cholera nearly six months before his son's birth. His mother, Ann Fairfax (Catlett) Hepburn, a schoolteacher, married George S. Hampton, who moved the family to Iowa in 1841 after his shipping business failed. After attempting to farm for two years, the family moved to Iowa City in 1843. There William entered school for the first time, attending irregularly for five years while working at a variety of jobs. He credited his apprenticeship at the Iowa City Republican, a Whig newspaper, as his greatest education. His fascination with politics inspired him to study law under William Penn Clarke in 1853. After passing the Illinois bar in 1854, he began practicing law in Chicago. The following year he married Melvina A. Morsman, and the couple eventually had five children. Shortly after their marriage, the couple moved to Marshalltown, Iowa, where William started his own law firm.

Hepburn began his political career by attending the first Iowa Republican convention in 1856. He gained political influence and was elected prosecuting attorney of Marshall County. When the Republican Party took control of Iowa's Sixth General Assembly in 1856, Hepburn's loyalty was rewarded with an appointment to the office of assistant clerk, and he served as chief clerk in 1858. Later that year Hepburn was elected district attorney of the Eleventh District. He remained active in the Republican Party, serving as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1860.

The outbreak of the Civil War left Hepburn torn between remaining at home and joining the war effort. After the Union's defeat at Bull Run, he helped organize Company B of the Second Iowa Volunteer Cavalry, which elected him as captain. He advanced to the ranks of major and eventually lieutenant colonel, and gained recognition for his valiant service at the Battle of Corinth. Following the war, Hepburn moved to Memphis and opened a law firm, but the effort was short-lived. In 1867 he moved to Clarinda, Iowa, to serve as editor and partial owner of the Page County Herald. He later opened a law office, which handled cases for the Burlington Railroad after it extended its line through Council Bluffs.

Politically, in the 1870s Hepburn backed the progressive wing of the Republican Party, supporting Horace Greeley for president. In 1880 he moved into the national political arena when he won the Republican nomination for the Eighth District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He defeated the incumbent William Sapp on the 385th ballot of the state Republican convention.

During his first six years in Washington, Hepburn supported the payment of veterans' pensions, criticized pork projects of the River and Harbor Bill, and lobbied for temperance reform. In 1886 Albert R. Anderson defeated Hepburn for reelection by focusing on the tariff and railroad regulation. Hepburn returned to his law practice in Clarinda, but remained politically active. In the Harrison administration, he served on the Pacific Railroad Commission and as solicitor of the treasury.

In 1892 Hepburn was reelected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Iowa's Eighth District and gradually rose to national political prominence. In 1895 he was appointed to chair the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. His work with President Theodore Roosevelt on the Hepburn Act was the culmination of his work on transportation issues. The Hepburn Act was also a centerpiece of President Roosevelt's public policies, which fostered social change and progressive reforms. When the law passed, it broadened the power of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to set maximum rates for shippers, increased the size of the ICC, outlawed pooling and rebates, set standardized accounting practices for all common carriers, and broadened the definition of common carriers to include pipelines, bridges, and terminals, bringing them under the control of the ICC.

Hepburn was involved in and outspoken on other progressive legislation. He coauthored the Pure Food and Drug Act. Its passage in 1906 inspired Roosevelt to declare that this would be one of the most productive Congresses in history. Hepburn also fought to reduce the power of the Speaker of the House and pushed for the annexation of Hawaii and the construction of the Panama Canal. He concurred with the Republican Party's opposition to the expansion of trade unions. As a reward for his partisanship, he chaired the Republican caucus from 1903 to 1909.

In 1908 Hepburn lost his bid for reelection, ending his political career. He remained in Washington for a couple of years, opening another law office, but he eventually returned to Clarinda, where he died in 1916. The Republican Party enjoyed the support of an impressive debater, speaker, and politician who was a leader in Iowa politics and a loyal Republican for 60 years. Newspapers across the country ran obituaries for the great Republican from Iowa. (Source: The University of Iowa)

More:

http://www.infoplease.com/encyclopedi...

https://archive.org/stream/wmpetershe...

http://gw.geneanet.org/tdowling?lang=...

http://history.house.gov/People/Detai...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William...

(no image)William Peters Hepburn by John Ely Briggs (no photo)

by Jesse Russell (no photo)

by Jesse Russell (no photo) by Benjamin F. Gue (no photo)

by Benjamin F. Gue (no photo) by Joseph Frazier Wall (no photo)

by Joseph Frazier Wall (no photo) by Johnson Brigham (no photo)

by Johnson Brigham (no photo)

William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst, (born April 29, 1863, San Francisco, California, U.S.—died August 14, 1951, Beverly Hills, California)American newspaper publisher who built up the nation’s largest newspaper chain and whose methods profoundly influenced American journalism.

Hearst was the only son of George Hearst, a gold-mine owner and U.S. senator from California (1886–91). The young Hearst attended Harvard College for two years before being expelled for antics ranging from sponsoring massive beer parties in Harvard Square to sending chamber pots to his professors (their images were depicted within the bowls). In 1887 he took control of the struggling San Francisco Examiner, which his father had bought in 1880 for political reasons. Hearst remade the paper into a blend of reformist investigative reporting and lurid sensationalism, and within two years it was showing a profit. He then entered the New York City newspaper market in 1895 by purchasing the theretofore unsuccessful New York Morning Journal. He hired such able writers as Stephen Crane and Julian Hawthorne and raided the New York World for some of Joseph Pulitzer’s best men, notably Richard F. Outcault, who drew the Yellow Kid cartoons. The New York Journal (afterward New York Journal-American) soon attained an unprecedented circulation as a result of its use of many illustrations, colour magazine sections, and glaring headlines; its sensational articles on crime and pseudoscientific topics; its bellicosity in foreign affairs; and its reduced price of one cent. Hearst’s Journal and Pulitzer’s World became involved in a series of fierce circulation wars, and these newspapers’ use of sensationalistic reporting and frenzied promotional schemes brought New York City journalism to a boil. Competition between the two papers, including rival Yellow Kid cartoons, soon gave rise to the term yellow journalism.

The Journal excoriated Great Britain in the Venezuela-British Guiana border dispute (from 1895) and then demanded (1897–98) war between the United States and Spain. Through dishonest and exaggerated reportage, Hearst’s newspapers whipped up public sentiment against Spain so much that they actually helped cause the Spanish-American War of 1898. Hearst supported William Jennings Bryan in the presidential campaign of 1896 and again in 1900, when he assailed President William McKinley as a tool of the trusts (the biggest companies in the United States).

While serving rather inactively in the U.S. House of Representatives (1903–07), Hearst received considerable support for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1904 and, running on an anti-Tammany Hall ticket, came within 3,000 votes of winning the 1905 election for mayor of New York City. In 1906, despite (or perhaps because of) his having turned to Tammany for support, he lost to Charles Evans Hughes for governor of New York, and in 1909 he suffered a worse defeat in the New York City mayoral election. Rebuffed in his political ambitions, Hearst continued to vilify the British Empire, opposed U.S. entry into World War I, and maligned the League of Nations and the World Court.

By 1925 Hearst had established or acquired newspapers in every section of the United States, as well as several magazines. He also published books of fiction and produced motion pictures featuring the actress Marion Davies, his mistress for more than 30 years. In the 1920s he built a grandiose castle on a 240,000-acre (97,000-hectare) ranch in San Simeon, California, and he furnished this residential complex with a vast collection of antiques and art objects that he had bought in Europe. At the peak of his fortune in 1935, he owned 28 major newspapers and 18 magazines, along with several radio stations, movie companies, and news services. But his vast personal extravagances and the Great Depression of the 1930s soon seriously weakened his financial position, and he had to sell faltering newspapers or consolidate them with stronger units. In 1937 he was forced to begin selling off some of his art collection, and by 1940 he had lost personal control of the vast communications empire that he had built. He lived the last years of his life in virtual seclusion. Hearst’s life was the basis for the movie Citizen Kane (1941).

At the beginning of the 21st century, the family-owned Hearst Corporation was still one of the largest media companies in the United States, with interests in magazines, broadcasting, and cartoon and feature syndicates.

(Source: Encyclopedia Britannica)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William...

http://www.biography.com/people/willi...

http://www.history.com/topics/william...

http://www.zpub.com/sf/history/willh....

http://hearstcastle.org/history-behin...

http://www.notablebiographies.com/Gi-...

http://www.hearstfdn.org/about/willia...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Wil...

by W. Joseph Campbell (no photo)

by W. Joseph Campbell (no photo) by Ben Procter (no photo)

by Ben Procter (no photo) by Oliver Carlson (no photo)

by Oliver Carlson (no photo) by Marion Davies (no photo)

by Marion Davies (no photo) by Daniel Alef (no photo)

by Daniel Alef (no photo) by Kenneth Whyte (no photo)

by Kenneth Whyte (no photo) by

by

David Nasaw

David Nasaw

Benjamin Ryan Tillman Jr.

Benjamin Ryan Tillman Jr.

Benjamin R. Tillman, byname Pitchfork Ben Tillman (born Aug. 11, 1847, Edgefield county, S.C., U.S.—died July 3, 1918, Washington, D.C.) outspoken U.S. populist politician who championed agrarian reform and white supremacy. Tillman served as governor of South Carolina (1890–94) and was a member of the U.S. Senate (1895–1918).

A farmer prior to his entry into politics, Tillman, a Democrat, emerged during the 1880s as a spokesman for poor rural whites in South Carolina in their conflict against both the ruling white aristocracy and the impoverished Negro population. The rise of Tillman marked the decline of the former Confederate general Wade Hampton as a political force in the state. Elected governor in 1890, Tillman translated his populist rhetoric into concrete reforms. He shifted the tax burden to the wealthy, improved public education, founded the agricultural college later to be known as Clemson University, and regulated the railroads. He also helped write the state constitution to disfranchise Negroes and circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment with a patchwork of Jim Crow laws (i.e., laws enforcing racial segregation). An unabashed bigot, he considered lynching an acceptable law-enforcement measure.

Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1894, Tillman served until his death, continuing to press for agrarian reform on the national level. He bitterly assailed Pres. Grover Cleveland for his hard-money policy, supporting instead the free-silver program of William Jennings Bryan. In most instances he opposed the administration of Pres. Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, the two became such bitter enemies that at one point the President barred Tillman from the White House. They put aside their differences long enough, however, to collaborate in securing passage of the Hepburn Act (1906), extending the Interstate Commerce Commission’s regulatory powers over the railroads. Tillman was floor leader for the bill. He generally supported Pres. Woodrow Wilson and, as chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, promoted the administration’s program to strengthen the Navy. His vituperative and often profane attacks on his political opponents earned him the nickname “Pitchfork Ben”; he once had a fistfight with his South Carolina colleague on the floor of the Senate. (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjami...

http://www.biography.com/people/benja...

http://projects.vassar.edu/1896/tillm...

http://www.charlestoncitypaper.com/ch...

http://www.sciway.net/hist/governors/...

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/55/

http://downwithtillman.com/

http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/h...

http://www.researchonline.net/sccw/bi...

(no image)The History Of South Carolina by Mary C. Simms Oliphant (no photo)

by Stephen Kantrowitz (no photo)

by Stephen Kantrowitz (no photo) by Francis Butler Simkins (no photo)

by Francis Butler Simkins (no photo) by Rayford W. Logan (no photo)

by Rayford W. Logan (no photo) by Bryant Simon (no photo)

by Bryant Simon (no photo)

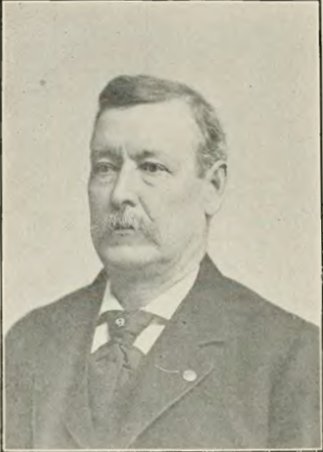

John Kean of New Jersey

John Kean of New Jersey

KEAN, John, (brother of Hamilton Fish Kean, great-grandson of John Kean [1756-1795], and uncle of Robert Winthrop Kean), a Representative and a Senator from New Jersey; born at ‘Ursino,’ near Elizabeth, N.J., December 4, 1852; studied in private schools and attended Yale College; graduated from the Columbia Law School, New York City, in 1875; admitted to the New Jersey bar in 1877, but did not engage in extensive practice; engaged in banking and interested in manufacturing; elected as a Republican to the Forty-eighth Congress (March 4, 1883-March 3, 1885); unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1884; elected to the Fiftieth Congress (March 4, 1887-March 3, 1889); unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1888; unsuccessful Republican candidate for Governor in 1892; member of the committee to revise the judiciary system of New Jersey; elected to the United States Senate in 1899; reelected in 1905, and served from March 4, 1899, to March 3, 1911; chairman, Committee on the Geological Survey (Fifty-seventh Congress), Committee to Audit and Control the Contingent Expenses (Fifty-eighth through Sixty-first Congresses); engaged in banking in Elizabeth, N.J.; died in Ursino, N.J., on November 4, 1914; interment in Evergreen Cemetery, Elizabeth, N.J.

(Source:Biographical Directory of the United States Congress)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ke...

http://politicalgraveyard.com/bio/kau...

http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty...

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/memb...

http://www.kean.edu/libertyhall/about...

http://www.nj.com/insidejersey/index....

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg....

http://bigoldhouses.blogspot.hr/2014/...

by Keith T. Poole (no photo)

by Keith T. Poole (no photo) by Kenneth C. Martis (no photo)

by Kenneth C. Martis (no photo) by Lawrence S. Rowland (no photo)

by Lawrence S. Rowland (no photo) by William Edgar Sackett (no info)

by William Edgar Sackett (no info) by Barbara G. Salmore ( no photo)

by Barbara G. Salmore ( no photo)

Thomas Brackett Reed

Thomas Brackett Reed

Thomas B. Reed, (born Oct. 18, 1839, Portland, Maine, U.S.—died Dec. 7, 1902, Washington, D.C.) vigorous U.S. Republican Party leader who, as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives (1889–91, 1895–99), introduced significant procedural changes (the Reed Rules) that helped ensure legislative control by the majority party in Congress.

After he was admitted to the bar in 1865, Reed began his law practice in Portland and was elected to the Maine House of Representatives in 1868 and to the state Senate two years later. He was elected to Congress on the Republican ticket in 1877 and served continuously until the end of the century. In 1882 he was appointed to the House Committee on Rules, and when the Republicans regained control of the House in 1889, Reed was elected speaker. As a strong speaker, he arranged for the control of the Rules Committee by the majority party in Congress.

The Reed Rules, adopted in February 1890, provided that every member present in the House must vote unless financially interested in a measure; that members present and not voting be counted for a quorum; and that no dilatory motions be entertained by the chair. Reed claimed these innovations enhanced legislative efficiency and helped ensure democratic (majority) control of the House; many thought they made a major contribution to the U.S. political system by establishing the principle of party responsibility. His dictatorial methods were bitterly attacked by the opposition, however, who called him Czar Reed. Nevertheless, the Reed Rules and methods were adopted by the Democratic leadership in 1891–95, and the power of the Rules Committee was increased.

Though denied the 1896 presidential nomination he had sought, Reed nonetheless supported the domestic programs of Pres. William McKinley and exercised a powerful influence in guiding bills through Congress. In 1899, however, he broke with the Republican administration over what he considered its expansionist policy toward Cuba and Hawaii. He resigned from the House in protest and retired to New York to practice law and to write. (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_...

http://www.npr.org/2011/05/29/1366892...

http://www.biography.com/people/thoma...

http://history.house.gov/Historical-H...

http://blog.oup.com/2015/03/thomas-re...

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/boo...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Tho...

http://leg.wa.gov/LawsAndAgencyRules/...

(no image)Thomas B. Reed, Parliamentarian by William Alexander Robinson (no photo)

(no image)From Hayes to McKinley by H. Wayne Morgan (no photo)

by Samuel W 1851-1923 McCall (no photo)

by Samuel W 1851-1923 McCall (no photo) by James Grant (no photo)

by James Grant (no photo) by Arthur Wallace Dunn (no photo)

by Arthur Wallace Dunn (no photo) by

by

Barbara W. Tuchman

Barbara W. Tuchman by

by

Mark Twain

Mark Twain

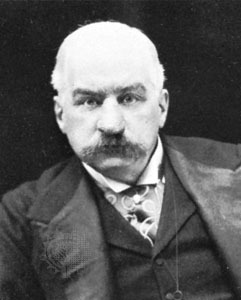

Jay Gould

Jay Gould

Jason "Jay" Gould (May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was a leading American railroad developer and speculator. He has been referred to as one of the ruthless robber barons of the Gilded Age, whose success at business made him the ninth richest U.S. citizen in history. Some modern historians like Walter R. Borneman working from primary sources have discounted his negative portrayal.

Early Career

His principal was credited as getting him a job working as a bookkeeper for a blacksmith. A year later the blacksmith offered him half interest in the blacksmith shop, which he sold to his father during the early part of 1854. Gould devoted himself to private study, emphasizing surveying and mathematics. In 1854, Gould surveyed and created maps of the Ulster County, New York area. In 1856 he published History of Delaware County, and Border Wars of New York, which he had spent several years writing.

In 1856, Gould entered a partnership with Zadock Pratt to create a tanning business in Pennsylvania in what would become Gouldsboro. Eventually, he bought out Pratt, who retired. In 1856, Gould entered another partnership with Charles Mortimer Leupp, a son-in-law of Gideon Lee, and one of the leading leather merchants in the United States at the time. Leupp and Gould was a successful partnership until the Panic of 1857. Leupp lost all his money, while Gould took advantage of the opportunity of the depreciation of property value and bought up former partnership properties for himself.

After the death of Charles Leupp, the Gouldsboro Tannery became a disputed property. Leupp's brother-in-law, David W. Lee, who was also a partner in Leupp and Gould, took armed control of the tannery. He believed that Gould had cheated the Leupp and Lee families in the collapse of the business. Eventually, Gould took physical possession, but was later forced to sell his shares in the company to Lee's brother.

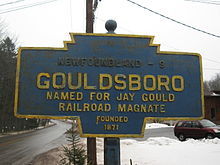

Keystone Marker for Gouldsboro, named after Jay Gould.

Railroad investing

In 1859 Gould began speculative investing by buying stock in small railways. Gould's father-in-law Daniel S. Miller was credited with introducing the younger man to the railroad industry, when he suggested that Gould help him save his investment in the Rutland and Washington Railroad in the Panic of 1857. Gould purchased stock for 10 cents on the dollar, which left him in control of the company.

Through the Civil War era, he did more speculation on railroad stocks in New York City. In 1863 he was appointed manager of the Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad.

The Erie Railroad encountered financial troubles in the 1850s, despite receiving loans from financiers Cornelius Vanderbilt and Daniel Drew. The Erie entered receivership in 1859 and was reorganized as the Erie Railway. Jay Gould, Drew and James Fisk engaged in stock manipulations known as the Erie War, with the result that in the summer of 1868 Drew, Fisk, and Vanderbilt lost control of the Erie, while Gould became its president.

Tweed Ring

It was during the same period that Gould and Fisk became involved with Tammany Hall, the New York City political ring. They made Boss Tweed a director of the Erie Railroad, and Tweed, in return, arranged favorable legislation for them. Tweed and Gould became the subjects of political cartoons by Thomas Nast in 1869. In October 1871, when Tweed was held on $1 million bail, Gould was the chief bondsman.

Black Friday

In August 1869, Gould and Fisk began to buy gold in an attempt to corner the market, hoping that the increase in the price of gold would increase the price of wheat such that western farmers would sell, causing a great amount of shipping of bread stuffs eastward, increasing freight business for the Erie railroad. During this time, Gould used contacts with President Ulysses S. Grant's brother-in-law, Abel Corbin, to try to influence the president and his Secretary General Horace Porter. These speculations in gold culminated in the panic of Black Friday, on September 24, 1869, when the premium over face value on a gold Double Eagle fell from 62 percent to 35 percent. Gould made a small profit from this operation, but lost it to subsequent lawsuits. The gold corner established Gould's reputation in the press as an all-powerful figure who could drive the market up and down at will.

Lord Gordon-Gordon

In 1873 Gould attempted to take control of the Erie Railroad by recruiting foreign investments from Lord Gordon-Gordon, whom he believed was a cousin of the wealthy Campbells looking to buy land for immigrants. He bribed Gordon-Gordon with $1 million in stock. But Gordon-Gordon was an impostor and cashed the stock immediately. Gould sued Gordon-Gordon; the case went to trial in March 1873. In court, Gordon-Gordon gave the names of the Europeans whom he claimed to represent, and was granted bail while the references were checked. He fled to Canada, where he convinced authorities that the charges against him were false.

After failing to convince or force Canadian authorities to hand over Gordon-Gordon, Gould and his associates, which included two future governors of Minnesota and three future members of Congress (Loren Fletcher, John Gilfillan, and Eugene McLanahan Wilson) attempted to kidnap him. The group snatched him successfully, but they were stopped and arrested by the North-West Mounted Police before they could return to the United States. The kidnappers were put in prison and refused bail.

This led to an international incident between the United States and Canada. Upon learning that the kidnappers were not given bail, Governor Horace Austin of Minnesota demanded their return; he put the local militia on a state of full readiness. Thousands of Minnesotans volunteered for a full military invasion of Canada. After negotiations, the Canadian authorities released the kidnappers on bail. The incident resulted in Gould losing any possibility of taking control of Erie Railroad.

Lord Gordon-Gordon

Western railroads

After being forced out of the Erie Railroad, Gould started to build up a system of railroads in the Midwest and West. He took control of the Union Pacific in 1873 when its stock was depressed by the Panic of 1873 and built a viable railroad that depended on shipments by local farmers and ranchers. Gould immersed himself in every operational and financial detail of the UP system. He built an encyclopedic knowledge, then acted decisively to shape its destiny. "He revised its financial structure, waged its competitive struggles, captained its political battles, revamped its administration, formulated its rate policies, and promoted the development of resources along its lines." After Gould's death, the Union Pacific slipped and declared bankruptcy during the Panic of 1893.

By 1879, Gould gained control of three more important western railroads, including the Missouri Pacific Railroad. He controlled 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of railway, about one-ninth of the length of rail in the United States at that time, and, by 1882, he had controlling interest in 15 percent of the country's trackage. Because the railroads were making profits and had control of rate setting, his wealth increased dramatically. When Gould withdrew from management of the Union Pacific in 1883 amidst political controversy over its debts to the federal government, he realized a large profit for himself. He obtained a controlling interest in the Western Union telegraph company, and, after 1881, in the elevated railways in New York City.

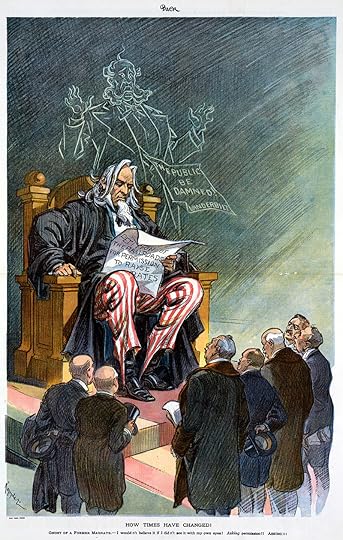

Cartoon depicting Wall Street as "Jay Gould's Private Bowling Alley"

Death

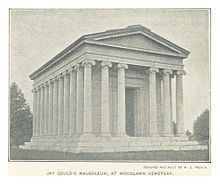

Gould died of tuberculosis on December 2, 1892, and was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx, New York. His fortune was conservatively estimated at $72 million for tax purposes, which he willed in its entirety to his family.

At the time of his death, Gould was a benefactor in the reconstruction of the Reformed Church of Roxbury, New York, now known as the Jay Gould Memorial Reformed Church. It is located within the Main Street Historic District and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. The family mausoleum was designed by Francis O'Hara. (Source: Wikipedia)

The mausoleum of Jay Gould (Source: Wikipedia)

More:

http://www.notablebiographies.com/Gi-...

http://www.biography.com/people/jay-g...

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h866...

http://www.britannica.com/biography/J...

http://history1800s.about.com/od/robb...

(no image) Jay Gould: The Story of a Fortune by Robert Warshow (no photo)

by Daniel Alef (no photo)

by Daniel Alef (no photo) by Charles R. Morris (no photo)

by Charles R. Morris (no photo) by

by

Maury Klein

Maury Klein by

by

Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould by

by

Edward J. Renehan Jr.

Edward J. Renehan Jr.

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt, (born May 27, 1794, Port Richmond, Staten Island, New York, U.S.—died January 4, 1877, New York, New York) American shipping and railroad magnate who acquired a personal fortune of more than $100 million.

The son of an impoverished farmer and boatman, Vanderbilt quit school at age 11 to work on the waterfront. In 1810 he purchased his first boat with money borrowed from his parents. He used the boat to ferry passengers between Staten Island and New York City. Then, during the War of 1812, he enlarged his operation to a small fleet, with which he supplied government outposts around the city.

Vanderbilt expanded his ferry operation still further following the war, but in 1818 he sold all his boats and went to work for Thomas Gibbons as steamship captain. While in Gibbons’s employ (1818–29), Vanderbilt learned the steamship business and acquired the capital that he used in 1829 to start his own steamship company.

During the next decade, Vanderbilt gained control of the traffic on the Hudson River by cutting fares and offering unprecedented luxury on his ships. His hard-pressed competitors finally paid him handsomely in return for Vanderbilt’s agreement to move his operation. He then concentrated on the northeastern seaboard, offering transportation from Long Island to Providence and Boston. By 1846 the Commodore was a millionaire.

The following year, he formed a company to transport passengers and goods from New York City and New Orleans to San Francisco via Nicaragua. With the enormous demand for passage to the West Coast brought about by the 1849 gold rush, Vanderbilt’s Accessory Transit Company proved a huge success. He quit the business only after his competitors—whom he had nearly ruined—agreed to pay him $40,000 (later it rose to $56,000) a month to abandon his operation.

By the 1850s he had turned his attention to railroads, buying up so much stock in the New York and Harlem Railroad that by 1863 he owned the line. He later acquired the Hudson River Railroad and the New York Central Railroad and consolidated them in 1869. When he added the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad in 1873, Vanderbilt was able to offer the first rail service from New York City to Chicago.

During the last years of his life, Vanderbilt ordered the construction of Grand Central Depot (the forerunner of Grand Central Terminal) in New York City, a project that gave jobs to thousands who had become unemployed during the Panic of 1873. Although never interested in philanthropy while acquiring the bulk of his huge fortune, later in his life he did give $1 million to Central University in Nashville, Tennessee. (later Vanderbilt University). In his will he left $90 million to his son William Henry, $7.5 million to William’s four sons, and—consistent with his lifelong contempt for women—the relatively small remainder to his second wife and his eight daughters. (Source: Britannica/Cornelius Vanderbilt)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corneli...

http://www.history.com/topics/corneli...

http://www.biography.com/people/corne...

http://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org...

http://www.library.vanderbilt.edu/spe...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Cor...

http://www.american-rails.com/corneli...

(no image) Cornelius Vanderbilt and the Railroad Industry by Lewis K. Parker (no photo)

by T.J. Stiles (no photo)

by T.J. Stiles (no photo) by Daniel Alef (no photo)

by Daniel Alef (no photo) by Jeffrey L. Rodengen (no photo)

by Jeffrey L. Rodengen (no photo) by Charles River Editors (no photo)

by Charles River Editors (no photo) by Adam Calvert (no photo)

by Adam Calvert (no photo) by

by

Edward J. Renehan Jr.

Edward J. Renehan Jr. by

by

Stephen Dando-Collins

Stephen Dando-Collins

Pure Food and Drug Act

Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration. Its main purpose was to ban foreign and interstate traffic in adulterated or mislabeled food and drug products, and it directed the U.S. Bureau of Chemistry to inspect products and refer offenders to prosecutors. It required that active ingredients be placed on the label of a drug’s packaging and that drugs could not fall below purity levels established by the United States Pharmacopeia or the National Formulary. The Jungle by Upton Sinclair was an inspirational piece that kept the public's attention on the important issue of unsanitary meat processing plants that later led to food inspection legislation.