The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Hard Times

Hard Times

>

Part III Chapters 01-05

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:

Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:"Mr. James Harthouse passed a whole night and a day in a state of so much hurry, that the World, with its best glass in his eye, would scarcely have recognized him during that insane interval, as the brother Jem of the honourable and jocular member. He was positively agitated. He several times spoke with an emphasis, similar to the vulgar manner. He went in and went out in an unaccountable way, like a man without an object. He rode like a highwayman. In a word, he was so horribly bored by existing circumstances, that he forgot to go in for boredom in the manner prescribed by the authorities.

After putting his horse at Coketown through the storm, as if it were a leap, he waited up all night: from time to time ringing his bell with the greatest fury, charging the porter who kept watch with delinquency in withholding letters or messages that could not fail to have been entrusted to him, and demanding restitution on the spot. The dawn coming, the morning coming, and the day coming, and neither message nor letter coming with either, he went down to the country house. There, the report was, Mr. Bounderby away, and Mrs. Bounderby in town. Left for town suddenly last evening. Not even known to be gone until receipt of message, importing that her return was not to be expected for the present."

So after following her to town he goes to Bounderby's town house but she isn't there, then he goes to the bank and finds that both Bounderby and Mrs. Sparsit are out of town and talking with Tom finds that he assumes his sister is still at their country house. He finally decides that the only thing he can do is go back to his hotel and wait, we are told:

"The hotel where he was known to live when condemned to that region of blackness, was the stake to which he was tied. As to all the rest—What will be, will be."

While he waits trying to read a newspaper, Sissy arrives. She tells Harthouse that he will never see Louisa again and that he must leave Coketown and swear never to return. Harthouse is taken aback at the appearance of Sissy at his quarters.

"A young woman whom he had never seen stood there. Plainly dressed, very quiet, very pretty. As he conducted her into the room and placed a chair for her, he observed, by the light of the candles, that she was even prettier than he had at first believed. Her face was innocent and youthful, and its expression remarkably pleasant. She was not afraid of him, or in any way disconcerted; she seemed to have her mind entirely preoccupied with the occasion of her visit, and to have substituted that consideration for herself.

‘I speak to Mr. Harthouse?’ she said, when they were alone.

‘To Mr. Harthouse.’ He added in his mind, ‘And you speak to him with the most confiding eyes I ever saw, and the most earnest voice (though so quiet) I ever heard.’

Harthouse seems taken with her beauty, we're told Sissy was even prettier than he first believed. I didn't remember her being beautiful, of course I don't remember a description of her beauty or lack of beauty at all. First Sissy tells him that she relies upon his honor to keep her visit and the reason for her visit secret. He gives his promise and Sissy tells him that Louisa is at her father's house and that he will never see her again. We are told this:

"Mr. Harthouse drew a long breath; and, if ever man found himself in the position of not knowing what to say, made the discovery beyond all question that he was so circumstanced. The child-like ingenuousness with which his visitor spoke, her modest fearlessness, her truthfulness which put all artifice aside, her entire forgetfulness of herself in her earnest quiet holding to the object with which she had come; all this, together with her reliance on his easily given promise—which in itself shamed him—presented something in which he was so inexperienced, and against which he knew any of his usual weapons would fall so powerless; that not a word could he rally to his relief."

Baffled and feeling very ridiculous, Harthouse isn't able to resist Sissy’s simple, persuasive honesty, the narrator tells us that Sissy’s good-natured reproach touches Harthouse “in the cavity where his heart should have been”. He tells her that he had no particularly evil intentions, but glided on from one step to another with "a smoothness so perfectly diabolical, that I had not the slightest idea the catalogue was half so long until I began to turn it over". He agrees to leave Coketown forever. Once Sissy is gone he writes three notes, one to Bounderby announcing his retirement from that part of the country, another to Mr. Gradgrind that is very similar, and the final to his brother. This one says:

Dear Jack,

All up at Coketown. Bored out of the place, and going in for camels.

Affectionately,

Jem.

The chapter ends with Harthouse leaving Coketown forever.

"Almost as soon as the ink was dry upon their superscriptions, he had left the tall chimneys of Coketown behind, and was in a railway carriage, tearing and glaring over the dark landscape."

Chapter 3 is titled "Very Decided" and we begin with Mrs. Sparsit who now has a violent cold I will assume comes from following people around in the rain.

Chapter 3 is titled "Very Decided" and we begin with Mrs. Sparsit who now has a violent cold I will assume comes from following people around in the rain."The indefatigable Mrs. Sparsit, with a violent cold upon her, her voice reduced to a whisper, and her stately frame so racked by continual sneezes that it seemed in danger of dismemberment, gave chase to her patron until she found him in the metropolis; and there, majestically sweeping in upon him at his hotel in St. James’s Street, exploded the combustibles with which she was charged, and blew up. Having executed her mission with infinite relish, this high-minded woman then fainted away on Mr. Bounderby’s coat-collar."

Even though she is now stricken with a bad cold and can barely talk she has managed to tell Bounderby what she witnessed between Louisa and Harthouse and then and fainted at the feet of the great "self-made man." The first thing Bounderby does on hearing this news is to administer restoratives," such as screwing the patient’s thumbs, smiting her hands, abundantly watering her face, and inserting salt in her mouth". Then he drags Mrs. Sparsit to Stone Lodge, where he confronts Gradgrind about Louisa’s infidelity. When Bounderby learns that Louisa hasn't run away with Harthouse but is at Stone Lodge he turns on Mrs. Sparsit and demands she apologize. She finds that she is too ill to do so and he sends her back to the bank. I wonder if she will apologize when she feels better? I doubt it. Bounderby now learns that Louisa's father proposes to keep her for a while, and he becomes furious. Gradgrind tells Bounderby that he fears he has made a mistake in Louisa’s upbringing and reminds Bounderby that as Louisa’s husband and also her elder, he should try to do what is best for her.

‘In the course of a few hours, my dear Bounderby,’ Mr. Gradgrind proceeded, in the same depressed and propitiatory manner, ‘I appear to myself to have become better informed as to Louisa’s character, than in previous years. The enlightenment has been painfully forced upon me, and the discovery is not mine. I think there are—Bounderby, you will be surprised to hear me say this—I think there are qualities in Louisa, which—which have been harshly neglected, and—and a little perverted. And—and I would suggest to you, that—that if you would kindly meet me in a timely endeavour to leave her to her better nature for a while—and to encourage it to develop itself by tenderness and consideration—it—it would be the better for the happiness of all of us. Louisa,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, shading his face with his hand, ‘has always been my favourite child.’

And here is part of Bounderby's response to Gradgrind, even more Bounderby sounding than I expected:

‘ Because when Tom Gradgrind, with his new lights, tells me that what I say is unreasonable, I am convinced at once it must be devilish sensible. With your permission I am going on. You know my origin; and you know that for a good many years of my life I didn’t want a shoeing-horn, in consequence of not having a shoe. Yet you may believe or not, as you think proper, that there are ladies—born ladies—belonging to families—Families!—who next to worship the ground I walk on.’

Bounderby now delivers his ultimatum: if Louisa has not returned to his house by noon the next day, he will send her clothing and conclude that she prefers to stay with her family. Should she decide not to return, he will no longer be responsible for her but her father will. I was rather surprised that he did not demand her to return with him then and there but instead he leaves her with her father. I wonder if he was amazed when she didn't return the next day. The chapter ends with this:

"So Mr. Bounderby went home to his town house to bed. At five minutes past twelve o’clock next day, he directed Mrs. Bounderby’s property to be carefully packed up and sent to Tom Gradgrind’s; advertised his country retreat for sale by private contract; and resumed a bachelor life."

Chapter 4 is titled "Lost" and we find Bounderby does not let his broken marriage interfere with his business; he pursues the bank robbery with even more vigor, offering twenty pounds for Stephen's apprehension. We're told:

Chapter 4 is titled "Lost" and we find Bounderby does not let his broken marriage interfere with his business; he pursues the bank robbery with even more vigor, offering twenty pounds for Stephen's apprehension. We're told:"Consequently, in the first few weeks of his resumed bachelorhood, he even advanced upon his usual display of bustle, and every day made such a rout in renewing his investigations into the robbery, that the officers who had it in hand almost wished it had never been committed."

The boldly painted reward poster is read by those who can read to the others who cannot. Bounderby had it posted in the dead of night so that all the population of the town should see it at one time, "like a blow". Each person has his own ideas concerning the innocence or guilt of Stephen. To strengthen his position with the workers, Slackbridge capitalizes upon Stephen's "disgrace."

" For you remember how he stood here before you on this platform; you remember how, face to face and foot to foot, I pursued him through all his intricate windings; you remember how he sneaked and slunk, and sidled, and splitted of straws, until, with not an inch of ground to which to cling, I hurled him out from amongst us: an object for the undying finger of scorn to point at, and for the avenging fire of every free and thinking mind to scorch and scar! And now, my friends—my labouring friends, for I rejoice and triumph in that stigma—my friends whose hard but honest beds are made in toil, and whose scanty but independent pots are boiled in hardship; and now, I say, my friends, what appellation has that dastard craven taken to himself, when, with the mask torn from his features, he stands before us in all his native deformity, a What? A thief! A plunderer! ’

We are told that these men are still in the streets when Bounderby, Tom and Rachael come to call on Louisa. Bounderby has brought them to Louisa to confirm or to deny Rachael's story of Louisa and Tom's visit to Stephen's home that evening so long ago. She tells her husband that they were there that night and the reason for the visit was because she felt compassion for Stephen and wished to offer him assistance but he wouldn't accept it and only took two pounds promising to pay it back. Tom is upset when Louisa admits their visit to Stephen's room. Rachael believes that Louisa may have had something to do with Stephen's being accused of the robbery. She says:

"‘Oh, young lady, young lady,’ returned Rachael, ‘I hope you may be, but I don’t know! I can’t say what you may ha’ done! The like of you don’t know us, don’t care for us, don’t belong to us. I am not sure why you may ha’ come that night. I can’t tell but what you may ha’ come wi’ some aim of your own, not mindin to what trouble you brought such as the poor lad. I said then, Bless you for coming; and I said it of my heart, you seemed to take so pitifully to him; but I don’t know now, I don’t know!’

Louisa could not reproach her for her unjust suspicions; she was so faithful to her idea of the man, and so afflicted.

‘And when I think,’ said Rachael through her sobs, ‘that the poor lad was so grateful, thinkin you so good to him—when I mind that he put his hand over his hard-worken face to hide the tears that you brought up there—Oh, I hope you may be sorry, and ha’ no bad cause to be it; but I don’t know, I don’t know!’

Rachael tells them that when she saw and heard the lies they were saying about Stephen she wrote to him and she expects him to be back in two days to clear his name. When Bounderby says no such letter had gone to Stephen, she tells them he had to change his name to get any work.

‘What,’ said Rachael, with the tears in her eyes again, ‘what, young lady, in the name of Mercy, was left the poor lad to do! The masters against him on one hand, the men against him on the other, he only wantin to work hard in peace, and do what he felt right. Can a man have no soul of his own, no mind of his own? Must he go wrong all through wi’ this side, or must he go wrong all through wi’ that, or else be hunted like a hare?’

Sissy asks if Rachael mentions in her letter that the reason he is suspected is because he was seen loitering outside the bank and Rachael replies yes, she had told him in the letter. Sissy then tells her she would like to come see her the next evening to see if Stephen has returned and the three of them leave. Once they are gone Gradgrind asks Louisa if she believes that Stephen is guilty and she says no, not anymore.

‘I think I have believed it, father, though with great difficulty. I do not believe it now.’

‘That is to say, you once persuaded yourself to believe it, from knowing him to be suspected. His appearance and manner; are they so honest?’

‘Very honest.’

‘And her confidence not to be shaken! I ask myself,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, musing, ‘does the real culprit know of these accusations? Where is he? Who is he?’

His hair had latterly began to change its colour. As he leaned upon his hand again, looking gray and old, Louisa, with a face of fear and pity, hurriedly went over to him, and sat close at his side. Her eyes by accident met Sissy’s at the moment. Sissy flushed and started, and Louisa put her finger on her lip."

So from that I believe that not only does Louisa think that Tom committed the crime, but so does Sissy, I wonder if even Mr. Gradgrind suspects Tom. But the two days go by and Stephen doesn't arrive and there is no word from him. On the fourth day Rachael thought that perhaps he didn't get her letter and finally gives his address to Bounderby who sends men to that place and everyone expects them to come back with Stephen. Here is the end of the chapter:

" The messengers returned alone. Rachael’s letter had gone, Rachael’s letter had been delivered. Stephen Blackpool had decamped in that same hour; and no soul knew more of him. The only doubt in Coketown was, whether Rachael had written in good faith, believing that he really would come back, or warning him to fly. On this point opinion was divided.

Six days, seven days, far on into another week. The wretched whelp plucked up a ghastly courage, and began to grow defiant. ‘Was the suspected fellow the thief? A pretty question! If not, where was the man, and why did he not come back?’

Where was the man, and why did he not come back? In the dead of night the echoes of his own words, which had rolled Heaven knows how far away in the daytime, came back instead, and abided by him until morning."

Our last chapter this week is chapter 5 and is titled "Found" which makes perfect sense after the previous chapter being called "Lost", and I expected we would find Stephen by the end of this chapter. But I was wrong, we are still in the dark as to the whereabouts of Stephen Blackpool. We begin with this:

Our last chapter this week is chapter 5 and is titled "Found" which makes perfect sense after the previous chapter being called "Lost", and I expected we would find Stephen by the end of this chapter. But I was wrong, we are still in the dark as to the whereabouts of Stephen Blackpool. We begin with this:"Day and night again, day and night again. No Stephen Blackpool. Where was the man, and why did he not come back?

Every night, Sissy went to Rachael’s lodging, and sat with her in her small neat room. All day, Rachael toiled as such people must toil, whatever their anxieties. The smoke-serpents were indifferent who was lost or found, who turned out bad or good; the melancholy mad elephants, like the Hard Fact men, abated nothing of their set routine, whatever happened. Day and night again, day and night again. The monotony was unbroken. Even Stephen Blackpool’s disappearance was falling into the general way, and becoming as monotonous a wonder as any piece of machinery in Coketown."

So as we are told, the days pass; life goes on and at least Rachael finds a friend, Sissy, who shares her heartbreak and anxiety. Perhaps I can consider that another positive thing, Rachael and Sissy, in a muddle of negative things. Sissy visits Rachael every night as they wait for news of Stephen. Rachael tells Sissy that she is afraid that the person who really committed the crime murdered Stephen as he was returning home to stop him from telling his story, Rachael is so upset that Sissy says that on Sunday they will take a walk in the country to strengthen Rachael for another week. One night, as they are walking past Bounderby’s house, they see Mrs. Sparsit dragging an old woman by the throat out of a coach toward the house.

"The spectacle of a matron of classical deportment, seizing an ancient woman by the throat, and hauling her into a dwelling-house, would have been under any circumstances, sufficient temptation to all true English stragglers so blest as to witness it, to force a way into that dwelling-house and see the matter out. But when the phenomenon was enhanced by the notoriety and mystery by this time associated all over the town with the Bank robbery, it would have lured the stragglers in, with an irresistible attraction, though the roof had been expected to fall upon their heads. Accordingly, the chance witnesses on the ground, consisting of the busiest of the neighbours to the number of some five-and-twenty, closed in after Sissy and Rachael, as they closed in after Mrs. Sparsit and her prize; and the whole body made a disorderly irruption into Mr. Bounderby’s dining-room, where the people behind lost not a moment’s time in mounting on the chairs, to get the better of the people in front."

Once inside the house they recognize the woman as Mrs. Pegler. Mr. Bounderby had been upstairs with Mr. Gradgrind and Tom when they all enter and when the three of them enter the room Mrs. Sparsit announces to Bounderby she has found the old woman, who was seen in Blackpool’s apartment before the robbery, and has brought him the possible accessory to the crime for questioning.

"‘Sir,’ explained that worthy woman, ‘I trust it is my good fortune to produce a person you have much desired to find. Stimulated by my wish to relieve your mind, sir, and connecting together such imperfect clues to the part of the country in which that person might be supposed to reside, as have been afforded by the young woman, Rachael, fortunately now present to identify, I have had the happiness to succeed, and to bring that person with me—I need not say most unwillingly on her part. It has not been, sir, without some trouble that I have effected this; but trouble in your service is to me a pleasure, and hunger, thirst, and cold a real gratification."

Bounderby does not react at all the way she expected him to, but far from being pleased Bounderby is furious and we find out that the mysterious Mrs. Pegler is really Bounderby's mother. Whether her name is Pegler or Bounderby I don't know. And now to the astonishment of everyone there we find that Bounderby not only had clothing, shoes, and food when he was a child, but he never slept in either an egg box or a ditch. At first Mr. Gradgrind still seems to believe in Bounderby for he asks the woman how she could abandon him in his infancy to his drunken grandmother, and left in the gutter, she replies:

"‘Josiah in the gutter!’ exclaimed Mrs. Pegler. ‘No such a thing, sir. Never! For shame on you! My dear boy knows, and will give you to know, that though he come of humble parents, he come of parents that loved him as dear as the best could, and never thought it hardship on themselves to pinch a bit that he might write and cipher beautiful, and I’ve his books at home to show it! Aye, have I!’ said Mrs. Pegler, with indignant pride. ‘And my dear boy knows, and will give you to know, sir, that after his beloved father died, when he was eight years old, his mother, too, could pinch a bit, as it was her duty and her pleasure and her pride to do it, to help him out in life, and put him ’prentice. And a steady lad he was, and a kind master he had to lend him a hand, and well he worked his own way forward to be rich and thriving. And I’ll give you to know, sir—for this my dear boy won’t—that though his mother kept but a little village shop, he never forgot her, but pensioned me on thirty pound a year—more than I want, for I put by out of it—only making the condition that I was to keep down in my own part, and make no boasts about him, and not trouble him. And I never have, except with looking at him once a year, when he has never knowed it. And it’s right,’ said poor old Mrs. Pegler, in affectionate championship, ‘that I should keep down in my own part, and I have no doubts that if I was here I should do a many unbefitting things, and I am well contented, and I can keep my pride in my Josiah to myself, and I can love for love’s own sake! And I am ashamed of you, sir,’ said Mrs. Pegler, lastly, ‘for your slanders and suspicions. And I never stood here before, nor never wanted to stand here when my dear son said no. And I shouldn’t be here now, if it hadn’t been for being brought here. And for shame upon you, Oh, for shame, to accuse me of being a bad mother to my son, with my son standing here to tell you so different!’

And Bounderby is there to tell us differently, walking up and down the room during this entire conversation, but when he finally talks it isn't to defend his mother but to tell everyone else to leave his house.

‘I don’t exactly know,’ said Mr. Bounderby, ‘how I come to be favoured with the attendance of the present company, but I don’t inquire. When they’re quite satisfied, perhaps they’ll be so good as to disperse; whether they’re satisfied or not, perhaps they’ll be so good as to disperse. I’m not bound to deliver a lecture on my family affairs, I have not undertaken to do it, and I’m not a going to do it. Therefore those who expect any explanation whatever upon that branch of the subject, will be disappointed—particularly Tom Gradgrind, and he can’t know it too soon. In reference to the Bank robbery, there has been a mistake made, concerning my mother. If there hadn’t been over-officiousness it wouldn’t have been made, and I hate over-officiousness at all times, whether or no. Good evening!'

And we're told that the Bully of humanity now cuts a most ridiculous figure. Rachael and Sissy leave together along with Mr. Gradgrind and speak of Stephen, Gradgrind "with much interest". As for Tom, we're told he sticks close to Bounderby on all occasions seeming to feel that as long as he is close to that man he was safe from any discovery. We are again told that even though Louisa and Sissy don't speak of it, they both suspect it is Tom who has committed the crime. No kidding. And so the chapter ends still without any sign of Stephen.

"And still the forced spirit which the whelp had plucked up, throve with him. If Stephen Blackpool was not the thief, let him show himself. Why didn’t he?

Another night. Another day and night. No Stephen Blackpool. Where was the man, and why did he not come back?"

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,We are getting close, the end is in sight, almost. We are now at the last part of the book, Part III, and the first chapter of this section is titled "Another Thing Needful". Th..."

"Another Thing Needful" shows us that love can also rule a person's life. As Kim noted, the first chapter of the novel gave us the notion that facts rule the world. Well, that notion has been dispelled.

I find it interesting that Dickens has written an industrial novel but has given each of its three divisions an agrarian focus. The first section was titled "Sowing" and in it we were introduced to a world that believed it had discovered how to plant for the future. Facts, not emotion; statistics, not imagination; calculation, not creativity. The next section is titled "Reaping" and here we see how the Benthamite world of regulation impacts the various characters. Now we come to the third section titled "Garnering." What is the result of the Benthamite world? Is the self-help world of Samuel Smiles one that needs to be followed for success in the new industrial world?

Kim wrote: "Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:

Kim wrote: "Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:"Mr. James Harthouse passe..."

Sissy proves that there can be great strength within a good and kind heart. She is able to both stand up to, and defeat, Harthouse and send him packing. As he leaves Coketown we are told that "he ... left the tall chimneys of Coketown behind, and was in a railway carriage, tearing and glaring over the dark landscape." There is a violence in the words " tearing and glaring," a suggestion that Harthouse has not learned his lesson of respecting the emotions and obligations of others. While chased from Coketown, Harthouse, and those like him are a dangerous class of people who will continue to prey on others.

As we approach the end of this novel Dickens begins to draw the various characters to their final positions and rolls. Sissy becomes aligned with Rachael, Bounderby is unmasked for the vile hypocrite he is and Thomas Gradgrind senior is becoming a character who deserves our pity. Indeed, Gradgrind senior is a man who is undergoing a sea-change in his beliefs and insights. I feel for him. Like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, he is experiencing an awakening of his being, almost a rebirth of sorts.

As we approach the end of this novel Dickens begins to draw the various characters to their final positions and rolls. Sissy becomes aligned with Rachael, Bounderby is unmasked for the vile hypocrite he is and Thomas Gradgrind senior is becoming a character who deserves our pity. Indeed, Gradgrind senior is a man who is undergoing a sea-change in his beliefs and insights. I feel for him. Like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, he is experiencing an awakening of his being, almost a rebirth of sorts.

Kim wrote: "Thinking more of the title of this chapter "Another Needful Thing" brings to mind that the first chapter of the first part is "The One Needful Thing". So it appears that Gradgrind has finally learned that facts are not the one needful thing, but more is needed to have a happy and fulfilling life."

Kim wrote: "Thinking more of the title of this chapter "Another Needful Thing" brings to mind that the first chapter of the first part is "The One Needful Thing". So it appears that Gradgrind has finally learned that facts are not the one needful thing, but more is needed to have a happy and fulfilling life."Very much so. Wisdom, or at least a smidgen of it, comes to Gradgrind at last. Will it be too late?

Kim wrote: "Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:

Kim wrote: "Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:"Mr. James Harthouse passe..."

I admire Sissy in this chapter, but I'm not sure I'm persuaded that we are given adequate explanation for how she has suddenly gotten so assertive and wise. We have to remember that she is still under Gradgrind's roof and thumb. It's not at all convincing to me that she could have developed so quickly.

Our first chapter this week opens with this:

Our first chapter this week opens with this: It seemed, at first, as if all that had happened since the days when these objects were familiar to her were the shadows of a dream; but gradually, as the objects became more real to her sight, the events became more real to her mind.

I immediately wondered what objects Louisa would have had in her room as a child. Certainly no dolls or rocking horses. She would have only had utilitarian items: wash basin, comb, brush, button hook, etc. I suppose even these useful things can offer some nostalgia for her.

Then Louisa has this conversation with her sister:

‘It was you who made my room so cheerful, and gave it this look of welcome?’

‘Oh no, Louisa, it was done before I came. It was — ’

Louisa turned upon her pillow, and heard no more.

It could only have been Sissy. What exactly did she do to make the room so cheerful?

Then Mr. Gradgrind comes in and has this to say:

‘Louisa,’ and his hand rested on her hair again, ‘I have been absent from here, my dear, a good deal of late; and though your sister’s training has been pursued according to — the system,’ he appeared to come to that word with great reluctance always, ‘it has necessarily been modified by daily associations begun, in her case, at an early age. I ask you — ignorantly and humbly, my daughter — for the better, do you think?’

‘Father,’ she replied, without stirring, ‘if any harmony has been awakened in her young breast that was mute in mine until it turned to discord, let her thank Heaven for it, and go upon her happier way, taking it as her greatest blessing that she has avoided my way.’

‘O my child, my child!’ he said, in a forlorn manner, ‘I am an unhappy man to see you thus! What avails it to me that you do not reproach me, if I so bitterly reproach myself!’ He bent his head, and spoke low to her. ‘Louisa, I have a misgiving that some change may have been slowly working about me in this house, by mere love and gratitude: that what the Head had left undone and could not do, the Heart may have been doing silently. Can it be so?’

What are we to make of this, than that Sissy, in her quiet, earnest way, has been slowly melting the heart of the grinch? Is this believable? It's certainly a plot that has made it's way to other stories -- Pollyanna, Anne of Green Gables, Little Lord Fauntleroy, & Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm are just a few that employ an angelic orphan to brighten the lives of the sourpusses who have taken them in. But Gradgrind wasn't unhappy, just eminently practical. And we didn't really see Sissy and Gradgrind interact so that we could watch the change come about. So it's a bit harder for me to buy into this softening, if you will, of Gradgrind to the "other thing needful."

Like Gradgrind's rapid change, I also found Harthouse's departure hard to believe. Once again, Sissy's angelic ways have worked their miracles.

Like Gradgrind's rapid change, I also found Harthouse's departure hard to believe. Once again, Sissy's angelic ways have worked their miracles. Does anyone remember the scene in Ben Hur when Jesus gives Judah water and the Roman soldier comes over to give him hell (so to speak), but when Jesus stands up and faces the soldier, he looks all befuddled and backs off? That's kind of how I'm picturing everyone's reaction to Sissy. :-)

Did anyone else think there might be some foreshadowing in the following passage? I don't know, but can't help but think that Harthouse might have a hand in reuniting Sissy with either her father or her circus family before the end of our story.

‘My name?’ said the ambassadress.

‘The only name I could possibly care to know, tonight.’

‘Sissy Jupe.’

‘Pardon my curiosity at parting. Related to the family?’

‘I am only a poor girl,’ returned Sissy. ‘I was separated from my father — he was only a stroller — and taken pity on by Mr Gradgrind. I have lived in the house ever since.’

She was gone.

...‘The defeat may now be considered perfectly accomplished. Only a poor girl — only a stroller — only James Harthouse made nothing of — only James Harthouse a Great Pyramid of failure.’

Kim wrote: "Accordingly, the chance witnesses on the ground, consisting of the busiest of the neighbours to the number of some five-and-twenty, closed in after Sissy and Rachael, as they closed in after Mrs. Sparsit and her prize; and the whole body made a disorderly irruption into Mr. Bounderby’s dining-room, where the people behind lost not a moment’s time in mounting on the chairs, to get the better of the people in front..."

Kim wrote: "Accordingly, the chance witnesses on the ground, consisting of the busiest of the neighbours to the number of some five-and-twenty, closed in after Sissy and Rachael, as they closed in after Mrs. Sparsit and her prize; and the whole body made a disorderly irruption into Mr. Bounderby’s dining-room, where the people behind lost not a moment’s time in mounting on the chairs, to get the better of the people in front..."This scene had me chuckling. Imagine Bounderby's surprise! Reminded me of the scene in "Love Actually" in which the whole neighborhood follows Colin Firth into the restaurant to propose to Aurelia. Everyone likes a good show. :-)

(You may see a pattern in my posts. Everything seems to remind me of some scene in another book or movie and I feel compelled to point it out. Hopefully the references resonate with a few of you, at least occasionally!)

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "Accordingly, the chance witnesses on the ground, consisting of the busiest of the neighbours to the number of some five-and-twenty, closed in after Sissy and Rachael, as they closed in ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "Accordingly, the chance witnesses on the ground, consisting of the busiest of the neighbours to the number of some five-and-twenty, closed in after Sissy and Rachael, as they closed in ..."Mary Lou

Thank you for your insightful comments (and movie references.) You have given us lots to ponder. Dickens's portrayal of Sissy's character is one that is certainly central to some of the novel's major themes. Reflecting on what you have said above here's my thoughts.

Sissy's presence is first observed at the very beginning of the book. In quick succession she is humiliated at school, abandoned by her father and then adopted by the Gradgrinds. Then, for seemingly a long time, Sissy fades into the background as the central plot follows the Bounderby subplots with Mrs. Sparsit, Bounderby's marriage, the mysterious old woman who hovers by Bounderby's door, the sorrows of Stephen and Rachael, and the Tom the whelp with Harthouse the devilish tempter all sharing centre stage at different times.

I believe we are to imagine that during this series of distressful events there is within the confines of Gradgrind's house the presence of a spirit of hope, love and optimism. Slowly, but surely, Sissy's presence evokes a positive change in the Gradgrind children and Mrs. Gradgrind. Mrs. Gradgrind may not be able to define what is exactly happening, even on her deathbed, but she does know that there is some presence in the house that is good. For her part, Sissy must obviously adopt to the family and the Gradgrind way of life; however, I think that the family, perhaps unwittingly, and even unawares, begin to gravitate towards her spirit of faith, belief and kindness.

Earlier in the novel we learn that Sissy kept the potion she fetched for her father to cure his ills. Sissy said at that time she would keep it until she saw her father again. Symbolically, I see this potion and Sissy's faith in its powers being transferred to the Gradgrind's, who are her new family. While Sissy's positive presence in the Gradgrind house may not be a major seismic event, it is a constant one. Sissy's name is really Cecelia and Cecelia was the patron saint of music. Sissy has brought harmony to the Gradgrind home. In our upcoming commentary this weekend we will see if she has any more gifts to give to the novel's characters.

Gradgrind has changed, to Louisa's benefit. Now we have to see whether Bounderby will also change and deserve to get Louisa back by making her happy and loved in her marriage.

Gradgrind has changed, to Louisa's benefit. Now we have to see whether Bounderby will also change and deserve to get Louisa back by making her happy and loved in her marriage. Any bets on this??

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "Chapter 2 is titled "Very Ridiculous" and we find James Harthouse extremely agitated trying to find out where Louisa is and why she hadn't kept her appointment with him:"Mr. James Har..."

I agree Everyman. It seems to break with the textual integrity when Sissy has grown considerably strong and wise, when we know she has been confined to the Gradgrind's, so life has not changed. It doesn't fit with the context of her story. I wonder if we learn more of where this came from.

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "Accordingly, the chance witnesses on the ground, consisting of the busiest of the neighbours to the number of some five-and-twenty, closed in after Sissy and Rachael, as they closed in ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "Accordingly, the chance witnesses on the ground, consisting of the busiest of the neighbours to the number of some five-and-twenty, closed in after Sissy and Rachael, as they closed in ..."Lol. Yep, I can visualise the interest, just like in "Love Actually".

Peter wrote: "While chased from Coketown, Harthouse, and those like him are a dangerous class of people who will continue to prey on others."

Peter wrote: "While chased from Coketown, Harthouse, and those like him are a dangerous class of people who will continue to prey on others."I am afraid that Harthouse will not meet his comeuppance in one of the following chapters just as people like he generally escape poetic justice in real life. What I find very remarkable is that - as the narrator points out - the one episode in his life in which he shows some decency and honour is the only episode of which he genuinely feels ashamed. This shows how cynical Harthouse really is - cynical in a bad sense, not in the sense of a disappointed romantic.

I really liked your way of pointing out Sissy Jupe's role in the novel, Peter, the softening, untiringly beneficial and yet very inconspicuous influence she is exerting on the Gradgrind family. We can best see it in Jane, but also in Mrs. Gradgrind - as early as somewhere in the first or second part, where Louisa says that Sissy has a very good way of dealing with her mother. And yet, and yet, and yet ... I cannot really imagine that somebody like Mr. Harthouse - a disillusioned, unscrupulous cynic (not one of the other sort, who turned cynic because he was disgusted with society and found his better hopes in mankind disappointed) - would allow himself to be influenced by her honest and self-confident manner. Mr. Harthouse would have had to have one grain of decency in him to be susceptible to Sissy's earnest pleading.

One might say that his avowal of never having plotted Louisa's seduction well in advance could be a sign of his not being completely vile - but I would argue that this underlines his lack of principle and decency even more. In addition, the way he describes himself in his self-apology evokes, to my mind, the idea of a gliding serpent: "I beg to be allowed to assure you that I have had no particularly evil intentions, but have glided on from one step to another with a smoothness so perfectly diabolical, that I had not the slightest idea the catalogue was half so long until I began to turn it over."

I still cannot figure this out properly.

Jane seems to have grown up very well under the soothing influence of Sissy Jupe - but as far as I remember Gradgrind had five children all in all. Whatever happened to "Adam Smith" and "Malthus"? Have their auspicious names moved them beyond the ken of redemption?

Jane seems to have grown up very well under the soothing influence of Sissy Jupe - but as far as I remember Gradgrind had five children all in all. Whatever happened to "Adam Smith" and "Malthus"? Have their auspicious names moved them beyond the ken of redemption?

Mary Lou wrote: "Does anyone remember the scene in Ben Hur when Jesus gives Judah water and the Roman soldier comes over to give him hell (so to speak), but when Jesus stands up and faces the soldier, he looks all befuddled and backs off?"

Mary Lou wrote: "Does anyone remember the scene in Ben Hur when Jesus gives Judah water and the Roman soldier comes over to give him hell (so to speak), but when Jesus stands up and faces the soldier, he looks all befuddled and backs off?"Does anyone remember? Why, Mary Lou, this is my favourite scene from the movie, and I cannot watch it without some water and salt mysteriously gathering in the corners of my eyes. Thanks for bringing this memory up! :-)

It may be too early to form any judgment now but I must say that I did not overly enjoy reading this novel. While I do not say that this is a bad novel, I still claim that this typical Charles-Dickens-Feeling that always comes when one delves into one of his novels was missing here all in all.

It may be too early to form any judgment now but I must say that I did not overly enjoy reading this novel. While I do not say that this is a bad novel, I still claim that this typical Charles-Dickens-Feeling that always comes when one delves into one of his novels was missing here all in all. I liked his description of Coketown and also his bitter satire, and I enjoyed Mr. Bounderby and his peculiar relationship with Mrs. Sparsit. I also took interest in Louisa as one of the more ambiguous Dickens heroines, and one particularly moving and well-written scene to me was Mrs. Gradgind's death ...

On the other hand, I often had the impression that this was more of a - can you say this in English - programmatic novel (i.e. a novel that is supposed to support certain political or philosophical ideas) than a real Dickens novel with sparkling characters, fanciful imagination, dark mysteries etc. etc.

However, my ramblings might belong more into next week's thread "Reflexions on the novel as a whole", so I'll interrupt them here.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "While chased from Coketown, Harthouse, and those like him are a dangerous class of people who will continue to prey on others."

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "While chased from Coketown, Harthouse, and those like him are a dangerous class of people who will continue to prey on others."I am afraid that Harthouse will not meet his comeuppan..."

I think Dickens has Sissy's presence in the novel, and especially within the Gradgrind home, evolve from more than one level. First, throughout the novel we have elements of a fairy tale structure, complete with an ogre, Bounderby, a wicked witch, Mrs. Sparsit, a gloomy, smoky place, Coketown, a dysfunctional family, the Gradgrind's, the evil, devil-like temptor, Harthouse who confront the presence of the forces of gentleness, kindness and inner strength, represented by Sissy. There are bits and pieces of this fragmented take scattered throughout the novel.

Second, we have the "high noon showdown". ( sorry, but I don't know my Western movies too well :-)). When Sissy confronts Harthouse one would think his experienced cynicism, lack of moral fibre and his portrayal earlier in the novel as being devil-like would easily overcome the young, innocent Sissy. Dickens lets us know that Harthouse sees in Sissy a young attractive woman, and, under different circumstances, a suitable future conquest for his lust. This is not to be for Sissy's strength of purpose, her mission to guard the Gradgrind family, and especially Louisa, from his languid lust, overcomes Harthouse. And so Harthouse literally writes off Coketown as a place to be in a letter and sets off somewhere else. The description of the train ride out of Coketown tells us that Harthouse's evil ways have not been conquered, only chased from the door of those who Sissy loves and is prepared to defend.

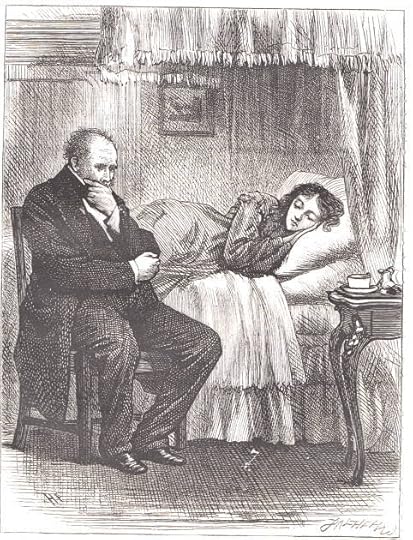

Here is an illustration by Harry French for this installment:

Here is an illustration by Harry French for this installment:

[image error]

Part III, Chapter 1

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘My dear Louisa. My poor daughter.’ He was so much at a loss at that place, that he stopped altogether. He tried again.

‘My unfortunate child.’ The place was so difficult to get over, that he tried again.

‘It would be hopeless for me, Louisa, to endeavour to tell you how overwhelmed I have been, and still am, by what broke upon me last night. The ground on which I stand has ceased to be solid under my feet. The only support on which I leaned, and the strength of which it seemed, and still does seem, impossible to question, has given way in an instant. I am stunned by these discoveries. I have no selfish meaning in what I say; but I find the shock of what broke upon me last night, to be very heavy indeed.’

She could give him no comfort herein. She had suffered the wreck of her whole life upon the rock.

‘I will not say, Louisa, that if you had by any happy chance undeceived me some time ago, it would have been better for us both; better for your peace, and better for mine. For I am sensible that it may not have been a part of my system to invite any confidence of that kind. I had proved my—my system to myself, and I have rigidly administered it; and I must bear the responsibility of its failures. I only entreat you to believe, my favourite child, that I have meant to do right.’

He said it earnestly, and to do him justice he had. In gauging fathomless deeps with his little mean excise-rod, and in staggering over the universe with his rusty stiff-legged compasses, he had meant to do great things. Within the limits of his short tether he had tumbled about, annihilating the flowers of existence with greater singleness of purpose than many of the blatant personages whose company he kept.

‘I am well assured of what you say, father. I know I have been your favourite child. I know you have intended to make me happy. I have never blamed you, and I never shall.’

He took her outstretched hand, and retained it in his."

Commentary:

French's fifteenth plate reasserts Gradgrind's role as parent; but whereas he was firm disciplinarian in the first illustration, now he enacts the role of bedside watcher and caregiver, just as Louisa had for her mother in an earlier illustration. He does not resemble the nattily dressed, middle-aged man of earlier illustrations but here he is anxious, despondent, and even self-condemning as he accepts responsibility for what has befallen his daughter. Louisa in French's plate, too, seems different: her hair is disheveled and her eye sockets sunken. Although French has captioned the plate "'Only Entreat You To Believe, My Favourite Child, That I Have Meant To Do Right'" Gradgrind is silent, deep in thought, and Louisa appears to asleep, so that the moment illustrated must be just prior to the father's leaving his daughter's room."

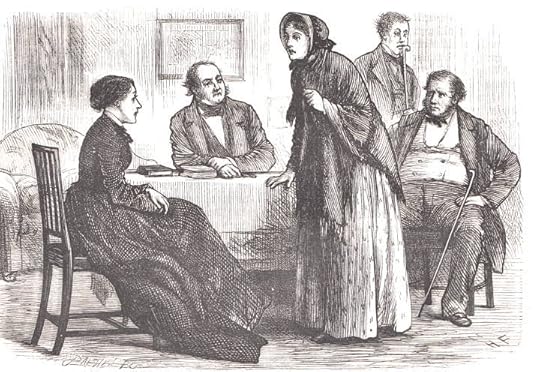

Here is another illustration by Harry French:

Here is another illustration by Harry French:

'You Have Seen Me Once Before, Young Lady,' Said Rachael"

Harry French

Part III, Chapter 4

Text Illustrated:

"Mrs. Bounderby,’ said her husband, entering with a cool nod, ‘I don’t disturb you, I hope. This is an unseasonable hour, but here is a young woman who has been making statements which render my visit necessary. Tom Gradgrind, as your son, young Tom, refuses for some obstinate reason or other to say anything at all about those statements, good or bad, I am obliged to confront her with your daughter.’

‘You have seen me once before, young lady,’ said Rachael, standing in front of Louisa.

Tom coughed.

‘You have seen me, young lady,’ repeated Rachael, as she did not answer, ‘once before.’

Tom coughed again.

‘I have.’

Rachael cast her eyes proudly towards Mr. Bounderby, and said, ‘Will you make it known, young lady, where, and who was there?’

‘I went to the house where Stephen Blackpool lodged, on the night of his discharge from his work, and I saw you there. He was there too; and an old woman who did not speak, and whom I could scarcely see, stood in a dark corner. My brother was with me.’

Commentary:

"This illustration serves to connect the two lines of the narrative-pictorial plot through the figure of Rachel, and to subtly remind the reader of the gambit involving Tom (right rear) and the bank robbery, of which Stephen stands falsely accused. Both Gradgrind and Louisa have sufficiently recovered their composure to be in the same room as Bounderby, seated right, but effectively cut off from his estranged wife and quondam father-in-law by the figure of Rachel, recognizable from her bonnet and shawl in an earlier illustration, elements that are repeated to provided visual continuity. This group plate is only the third such composition in the sequence thus far; it amounts to a tableau vivant rather than a character study as it juxtaposes all figures in the scene at a precise moment, but fails to account for Sissy Jupe, who is also present in the text. Tom, obviously feeling alienated by his guilt, "remained standing in the obscurest part of the room, near the door"; in the plate, he is detached from the rest of the group, anxiously gnawing his cane."

An illustration by Charles S. Reinhart:

An illustration by Charles S. Reinhart:

"Forgive Me, Pity Me, Help Me!"

Charles S. Reinhart

Part III, Chapter 1

Illustration for Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1870.

Commentary:

"This illustration of perfect sympathy between the maternal poor girl, Sissy Jupe, who has grown to maturity in the Gradgrind Household, and Louisa, recently tempted to break her marriage vows, reminds one of Katherine Mansfield's remark in the short story "A Cup of Tea" that all women are sisters, and never more so than in adversity. This is Reinhart's sixth bedroom scene, but it is very different from the last of the series, in which, in the dark, Louisa attempted to serve as Tom's confessor. The text which the twelfth plate accompanies casts black-garbed Sissy in the role of priestly confessor to Louisa's supplicant. The color symbolism works in reverse, of course, since, although in white, Louisa confesses herself "quite devoid" of good, while Dickens almost canonizes "the stroller's child" as a compound of "brave affection," "devoted spirit," and moral beacon: "the once deserted girl shone like a beautiful light upon the darkness of the other" . The caption leaves the reader-viewer in constant anticipation until the very last line of the chapter, the moment Reinhart has chosen to realize. However, he has adjusted the juxtaposition of the two young women so that Louisa is not upon her knees, clinging desperately to Sissy as she cries out for "compassion" in almost biblical terms, as suggested in such words and phrases as "a guide to peace," "innocence," and "veneration."

Regarding the simple trust that each girl shows the other, one is struck prior to completing the reading of the chapter at the subtlety of the plate in contrast to the high Victorian sentimentality of the letter-press. Perhaps it was Dickens's chief failing that he heightened the language in both dialogue and description to command the reader's tears to flow when the situation presented faithfully should have won that reader's sympathy without rhetorical manipulation."

Another by Charles S. Reinhart:

Another by Charles S. Reinhart:

"If You Can't Get It Out, Ma'am," Said Bounderby, "Leave Me to Get It Out"

Charles S. Reinhart. 1870

Part III, Chapter 3

Illustration for Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1870.

Commentary:

"The chapter's initial setting is Mr. Bounderby's recently-rented suite in a London hotel in St. James's Street, a locale possibly so designated by Dickens because the St. James of the first century was called both "The Just" and "The Lord's Brother" in The New Testament; shortly back at Coketown, poetic justice will be meted out upon two of the story's villains. In a triply comedic comeuppance, Sissy has already dismissed James Harthouse; now Bounderby (Gradgrind's brother-in-arms in the Hard Fact political faction) dismisses Mrs. Sparsit, while Gradgrind (depicted here in a much less distorted and more normal form than in previous Reinhart illustrations) at last accepts the error of his anti-sentiment stance. The sketchily realized map of the world behind Gradgrind may be intended to suggest that, because he paid it too little attention, his own domestic world is collapsing about him. His hand to his brow (to ease the pain, or perhaps to block out the quarrel between Bounderby and Mrs. Sparsit), the exhausted father takes upon himself the blame for the marital breakup as he openly concedes to the son-in-law that his daughter has just left that "we are all liable to mistakes" (Book III, Ch. 3).

Finally, the formerly "indefatigable" Mrs. Sparsit cringes before Bounderby, who of course is looking for someone other than himself to blame for Louisa's humiliating him publicly by running off with Harthouse (he has not yet received Gradgrind's letter announcing the breakup of the marriage, and is still crediting Mrs. Sparsit's account of events). The "classical ruin" and "The Bully of Humility" have returned to Coketown by train and driven by coach to Stonelodge. Here he calls upon Mrs. Sparsit to recount for his father-in-law the conversation between his daughter and his "precious gentleman-friend". Bounderby's being disabused of his wife's conduct and his learning of her having returned to Stonelodge have already occurred before we encounter the illustration, which therefore underscores Bounderby's acting in ignorance of the facts and his misplaced faith in Mrs. Sparsit's account. Bounderby has asked for her apology for her "Cock-and-a-Bull" fabrication, but Mrs. Sparsit has taken refuge in tears."

Here is an illustration by Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Here is an illustration by Sol Eytinge, Jr.

"Mrs. Bounderby and Sissy"

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Part III, Chapter 1

Illustration for the Diamond Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge and Hard Times (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867).

Commentary:

In Eytinge's sixth and final full-page dual character study for the second novel in the compact American publication, the penitent intellectual, Louisa, has fled from her loveless marriage, aborted her romantic assignation with James Harthouse, and returned, distraught, to her father's house. In her denunciation of her father's educational system and suppression of sentiment, she has underscored for her hapless parent the utter folly of his emphasis on the wisdom of the head rather than the wisdom of the heart. The ensuing passage of dialogue occurs between Sissy and Louisa on the morning after her escape from Bounderby and Harthouse, in Book Three, "The Garnering," and has been realized is this illustration for the chapter "Another Thing Needful":

"I have always loved you, and have always wished that you should know it. But you changed to me a little, shortly before you left home. Not that I wondered at it. You knew so much, and I knew so little, and it was so natural in many ways, going as you were among other friends, that I had nothing to complain of, and was not at all hurt."

Her colour rose as she said it modestly and hurriedly. Louisa understood the loving pretence, and her heart smote her.

"May I try?" said Sissy, emboldened to raise her hand to the neck that was insensibly drooping towards her.

Louisa, taking down the hand that would have embraced her in another moment, held it in one of hers, and answered: —

"First, Sissy, do you know what I am? I am so proud and so hardened, so confused and troubled, so resentful and unjust to every one and to myself, that everything is stormy, dark, and wicked to me. Does not that repel you?"

"No!"

"I am so unhappy, and all that should have made me otherwise is so laid waste, that if I had been bereft of sense to this hour, and instead of being as learned as you think me, had to begin to acquire the simplest truths, I could not want a guide to peace, contentment, honor, all the good of which I am quite devoid, more abjectly than I do. Does not that repel you?"

"No!"

In the innocence of her brave affection, and the brimming up of her old devoted spirit, the once deserted girl shone like a beautiful light upon the darkness of the other.

Louisa raised the hand that it might clasp her neck and join its fellow there. She fell upon her knees, and clinging to this stroller's child, looked up at her almost with veneration.

"Forgive me, pity me, help me! Have compassion on my great need, and let me lay this head of mine upon a loving heart?"

"O, lay it here!" cried Sissy, — "Lay it here, my dear."

Although Eytinge has correctly identified this as a crucial scene in the development of Louisa's character and in her turning her back on a furtive life of illicit passion, his treatment of Sissy's comforting Louisa is deficient in terms of Charles Stanley Reinhart's realization of that very same moment in the American Household Edition's "Forgive Me, Pity Me, Help Me!", for the latter picture is both more convincingly rendered in terms of the modeling of the figures and tenderness in both women's faces. Moreover, perhaps shying away from depicting two young women on a bed together, Eytinge has altered the circumstances under which Sissy is comforting Louisa, and has, moreover, made Louisa much younger and smaller, as if she is prepubescent rather than a young adult. In all of these respects, Reinhart's treatment is more emotionally satisfying and more faithful to Dickens's intention, namely to show in our lives the value of sentiment, and the ever-constant possibility of embracing repentance rather than succumbing to temptation.

Thanks Kim. I always enjoy the illustrations and the commentary. I find in the commentaries ideas and ways to further analyse and enjoy the novel. With pictures, no less!

Thanks Kim. I always enjoy the illustrations and the commentary. I find in the commentaries ideas and ways to further analyse and enjoy the novel. With pictures, no less!

Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration by Harry French for this installment:

Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration by Harry French for this installment:Part III, Chapter 1

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition

I love Gradgrind in this photo -- he looks so completely bemused by this extraordinary turn of events! As if he's saying, "How could I have been so wrong?" and questioning everything he thought he knew - his very foundation is not on rock, but sand.

I'm not sure if Louisa is asleep or just has semi-lowered lids, but her face looks too peaceful to me. I wish he'd given her a furrowed brow or some other expression that better illustrates her angst.

Tristram wrote: "Jane seems to have grown up very well under the soothing influence of Sissy Jupe - but as far as I remember Gradgrind had five children all in all. Whatever happened to "Adam Smith" and "Malthus"? ..."

Tristram wrote: "Jane seems to have grown up very well under the soothing influence of Sissy Jupe - but as far as I remember Gradgrind had five children all in all. Whatever happened to "Adam Smith" and "Malthus"? ..."Great question. They have vanished. Why then did Dickens bother to introduce them in the first place? Weak plotting.

Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration by Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Kim wrote: "Here is an illustration by Sol Eytinge, Jr."Mrs. Bounderby and Sissy"

This is totally wrong. Louisa is shown as a girl and Sissy as a woman. Exactly the opposite.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Jane seems to have grown up very well under the soothing influence of Sissy Jupe - but as far as I remember Gradgrind had five children all in all. Whatever happened to "Adam Smith..."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Jane seems to have grown up very well under the soothing influence of Sissy Jupe - but as far as I remember Gradgrind had five children all in all. Whatever happened to "Adam Smith..."I think Dickens wanted to reference the socio-economic names directly into the narrative. Once Dickens had planted the names Adam Smith and Malthus he had no use of them as his plot line followed Louisa and Bitzer. In A Christmas Carol Dickens used Scrooge as a figure referencing the thoughts of Smith and Malthus.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 3

Kim wrote: "Chapter 3 'Yet you may believe or not, as you think proper, that there are ladies—born ladies—belonging to families—Families!—who next to worship the ground I walk on.’

He discharged this, like a Rocket, at his father-in-law's head."

Despite all the lives falling apart (or perhaps falling in place together), I enjoyed some of the comic touches of these chapters, like this line above. Considering Bounderby's treatment of family (both his own, Gradgrind's, and Mrs. Sparsit's), this struck me as a particularly absurd boast.

My footnote also suggests that the capitalized Rocket likely refers to a famous locomotive on the Liverpool-Manchester railway.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 4 is titled "Lost"

Kim wrote: "Chapter 4 is titled "Lost" "...set forth in this degrading and disgusting document, this blighting bill, this pernicious placard, this abominable advertisement... For you remember how he stood here before you on this platform; you remember how, face to face and foot to foot, I pursued him through all his intricate windings; you remember how he sneaked and slunk, and sidled, and splitted of straws..."

Slackbridge's alliteration-full speech in this chapter really gave me the impression that Dickens enjoyed writing it!

Tristram wrote: "I cannot really imagine that somebody like Mr. Harthouse - a disillusioned, unscrupulous cynic ... - would allow himself to be influenced by her honest and self-confident manner..."

Tristram wrote: "I cannot really imagine that somebody like Mr. Harthouse - a disillusioned, unscrupulous cynic ... - would allow himself to be influenced by her honest and self-confident manner..."Like many of you, I also found Harthouse's exit, and the resolution of this plot line (assuming this is the end of him) a bit too pat. I was thinking again about the comparison with Steerforth, who I don't think would have given up so easily. Perhaps the difference is Harthouse's conviction that indifference is the genuine high-breeding (the only conviction he had). Although both were privileged, Harthouse was better connected, and so more bred for boredom, so to speak. Perhaps he just couldn't justify the exertion in the face of Sissy's honesty and faith. It is puzzling.

But I was amused by Harthouse's summary of the men in Louisa's life:

taking advantage of her father's being a machine, or of her brother's being a whelp, or of her husband's being a bear!

Vanessa wrote: "Perhaps he just couldn't justify the exertion in the face of Sissy's honesty and faith.."

Vanessa wrote: "Perhaps he just couldn't justify the exertion in the face of Sissy's honesty and faith.."That's kind of what I was thinking. Harthouse doesn't seem to want to put much effort into anything unless he's finds it amusing. Now that Sissy, Gradgrind, and even Louisa were "onto him" so to speak, he knew it wasn't going to be fun anymore. On to the next diversion.

Vanessa wrote: "My footnote also suggests that the capitalized Rocket likely refers to a famous locomotive on the Liverpool-Manchester railway. ."

Vanessa wrote: "My footnote also suggests that the capitalized Rocket likely refers to a famous locomotive on the Liverpool-Manchester railway. ."Pretty certainly. The Rocket, btw, was designed and built by an ancestor of mine.

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "Perhaps he just couldn't justify the exertion in the face of Sissy's honesty and faith.."

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "Perhaps he just couldn't justify the exertion in the face of Sissy's honesty and faith.."That's kind of what I was thinking. Harthouse doesn't seem to want to put much effort into..."

Yes, and he seemed appalled by his own agitation, while waiting to hear from Louisa, and even spoke with a "vulgar" emphasis. I suspect he was really uncomfortable with how much he had invested in her.

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "My footnote also suggests that the capitalized Rocket likely refers to a famous locomotive on the Liverpool-Manchester railway. ."

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "My footnote also suggests that the capitalized Rocket likely refers to a famous locomotive on the Liverpool-Manchester railway. ."Pretty certainly. The Rocket, btw, was designed and built by an ancestor of mine."

Referenced in Hard Times -- how cool is that! What was the competition it won in 1829?

Peter wrote: "I think Dickens has Sissy's presence in the novel, and especially within the Gradgrind home, evolve from more than one level...."

Peter wrote: "I think Dickens has Sissy's presence in the novel, and especially within the Gradgrind home, evolve from more than one level...."Thanks for pointing out the layers in this novel, Peter. I also would have missed some of the biblical references, if not for the footnotes. I'm not sure how Sissy fits into it, except she appears like an Eve who refused to bite the apple of knowledge!

Mary Lou wrote:

Mary Lou wrote: "‘Louisa, I have a misgiving that some change may have been slowly working about me in this house, by mere love and gratitude: that what the Head had left undone and could not do, the Heart may have been doing silently. Can it be so?’

What are we to make of this, than that Sissy, in her quiet, earnest way, has been slowly melting the heart of the grinch? Is this believable? ..."

I took the change that Gradgrind speaks of, to be more about Jane than himself, since he begins with mentioning his absence from the house. After Louisa left, it seems that Sissy had been running the Gradgrind house while he was in London. I think the spark of compassion he had in taking Sissy in as a child, grows when he sees the impact on Louisa of growing up without it. It's sad that it's so late (for himself) and that he appears consumed by regret.

Vanessa wrote: " it seems that Sissy had been running the Gradgrind house while he was in London."

Vanessa wrote: " it seems that Sissy had been running the Gradgrind house while he was in London."Really good observation, Vanessa. Mrs. Gradgrind had been ill (and Sissy, undoubtedly her primary caretaker), leaving Sissy to be Jane's surrogate parent. I never thought about Gradgrind's absence from the house.

The Rocket information is interesting. Everyman, did your ancestor name it, as well? I think of it in terms of space travel, of course, so the fact that it was used in a 19th century book caught my eye. I looked up the etymology and got this:

Rocket comes ultimately from Italian rocca ‘a distaff’, the stick or spindle on which wool was wound for spinning. Like the firework, it was cylindrical in shape. The development of rockets for space travel after the Second World War gave rise to the expression not rocket science to suggest that something is not really very difficult. Rocket meaning ‘a reprimand’, as in to give or get a rocket, is Second World War military slang—the first recorded example is stop a rocket. The salad vegetable rocket is a totally different word, which came via French roquette from Latin eruca, meaning a kind of cabbage.

Then I looked for the image of the distaff on a spinning wheel:

The distaff is the vertical piece on the left. (Kim! I posted my first picture! Thanks!)

It fascinates me that we can follow a word through the centuries from a spinning wheel to a train to a space ship. What a wonderful world!

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: " it seems that Sissy had been running the Gradgrind house while he was in London."

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: " it seems that Sissy had been running the Gradgrind house while he was in London."Really good observation, Vanessa. Mrs. Gradgrind had been ill (and Sissy, undoubtedly her primary..."

Mary Lou

Thanks for the research and the picture. It's time I learn how to do it too.

Kim: Did you explain somewhere how to put a picture in with a commentary? If you did, I missed it. Any chance you could explain how to do it or point me in the right direction to find out?

Vanessa wrote: "Referenced in Hard Times -- how cool is that! What was the competition it won in 1829?"

Vanessa wrote: "Referenced in Hard Times -- how cool is that! What was the competition it won in 1829?"The Rainhill Trials.

According to Wikipedia:

The Rainhill Trials were an important competition in the early days of steam locomotive railways, run in October 1829 for the nearly completed Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Five engines competed, running back and forth along a mile length of level track at Rainhill, in Lancashire (now Merseyside).

Stephenson's Rocket was the only locomotive to complete the trials, and was declared the winner. The Stephensons were accordingly given the contract to produce locomotives for the railway.

We are getting close, the end is in sight, almost. We are now at the last part of the book, Part III, and the first chapter of this section is titled "Another Thing Needful". The chapter finds me still waiting for something positive to happen to someone, somewhere, just a little, can I have even that? At first I thought no it's still sad and depressing, but thinking more of it, Louisa is now back with her father, her rather rapidly changed father, and away from Bounderby, so that is positive. Also she will now have Sissy as part of her life and a sister who seems to have been influenced for the better by Sissy. Perhaps that's what happened to Gradgrind, after awhile Sissy made a difference in him. The chapter begins with Louisa waking and finding herself in her old room in her old bed. Her sister is beside her and when Louisa tells her sister what a beaming face she has Jane replies:

‘Have I? I am very glad you think so. I am sure it must be Sissy’s doing.’

Now Mr. Gradgrind comes in the room to see Louisa a changed man from what he was at the beginning of the novel.

"He had a jaded anxious look upon him, and his hand, usually steady, trembled in hers. He sat down at the side of the bed, tenderly asking how she was, and dwelling on the necessity of her keeping very quiet after her agitation and exposure to the weather last night. He spoke in a subdued and troubled voice, very different from his usual dictatorial manner; and was often at a loss for words.

‘My dear Louisa. My poor daughter.’ He was so much at a loss at that place, that he stopped altogether. He tried again.

‘My unfortunate child.’ The place was so difficult to get over, that he tried again.

‘It would be hopeless for me, Louisa, to endeavour to tell you how overwhelmed I have been, and still am, by what broke upon me last night. The ground on which I stand has ceased to be solid under my feet. The only support on which I leaned, and the strength of which it seemed, and still does seem, impossible to question, has given way in an instant. I am stunned by these discoveries. I have no selfish meaning in what I say; but I find the shock of what broke upon me last night, to be very heavy indeed.’

She could give him no comfort herein. She had suffered the wreck of her whole life upon the rock."

Thinking more of the title of this chapter "Another Needful Thing" brings to mind that the first chapter of the first part is "The One Needful Thing". So it appears that Gradgrind has finally learned that facts are not the one needful thing, but more is needed to have a happy and fulfilling life. Gradgrind goes on to say that perhaps the wisdom of the heart is better than wisdom of the head. Because Louisa and her father are so accustomed to living their lives according to the philosophy of fact, learning how to change their mode of thinking will be difficult, and most of the time Louisa doesn't answer her father or even look at him. She does tell him that she knows he was trying to make her happy and she doesn't blame him for anything. When her father leaves Sissy enters the room and at first Louisa pretends to be asleep, she knows who it is and she feels angry to have Sissy see her in her distress. Sissy just sits quietly with her hand upon Louisa's neck and brings about this change in her:

"It lay there, warming into life a crowd of gentler thoughts; and she rested. As she softened with the quiet, and the consciousness of being so watched, some tears made their way into her eyes. The face touched hers, and she knew that there were tears upon it too, and she the cause of them."

Sissy tells her she would like to help her, would like to be something to her the same way she is to Louisa's sister. At one point Louisa asks her, "Have I always hated you so much?" and I didn't remember that she hated her at all, I thought they had liked each other, so I went back and looked. I found this at the end of the first part, it happens when Mr. Gradgrind announces the engagement of Louisa and Bounderby:

"When Mr. Gradgrind had presented Mrs. Bounderby, Sissy had suddenly turned her head, and looked, in wonder, in pity, in sorrow, in doubt, in a multitude of emotions, towards Louisa. Louisa had known it, and seen it, without looking at her. From that moment she was impassive, proud and cold—held Sissy at a distance—changed to her altogether."

When Sissy asks again if she may try to help Louisa the chapter ends with this:

‘First, Sissy, do you know what I am? I am so proud and so hardened, so confused and troubled, so resentful and unjust to every one and to myself, that everything is stormy, dark, and wicked to me. Does not that repel you?’

‘No!’

‘I am so unhappy, and all that should have made me otherwise is so laid waste, that if I had been bereft of sense to this hour, and instead of being as learned as you think me, had to begin to acquire the simplest truths, I could not want a guide to peace, contentment, honour, all the good of which I am quite devoid, more abjectly than I do. Does not that repel you?’

‘No!’

In the innocence of her brave affection, and the brimming up of her old devoted spirit, the once deserted girl shone like a beautiful light upon the darkness of the other.

Louisa raised the hand that it might clasp her neck and join its fellow there. She fell upon her knees, and clinging to this stroller’s child looked up at her almost with veneration.

‘Forgive me, pity me, help me! Have compassion on my great need, and let me lay this head of mine upon a loving heart!’

‘O lay it here!’ cried Sissy. ‘Lay it here, my dear.’