The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Book I Chapters 23 - 25

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

The next Chapter is concerned with „Fortune-Telling“ and also with intensifying the connection between Pancks and Amy Dorrit. The Chapter starts with Little Dorrit, that self-same evening receiving a call from Mr. Plornish, who tells her that two ladies – evidently Flora and Mr. F.’s Aunt – have been making enquiries about her and left a card with their address.

The next Chapter is concerned with „Fortune-Telling“ and also with intensifying the connection between Pancks and Amy Dorrit. The Chapter starts with Little Dorrit, that self-same evening receiving a call from Mr. Plornish, who tells her that two ladies – evidently Flora and Mr. F.’s Aunt – have been making enquiries about her and left a card with their address.Interestingly, before Mr. Plornish can impart this information to Amy, he first of all has to go through a series of coughs, inducing her to leave the room in order to maintain the fiction of Mr. Dorrit not knowing anything about Amy’s work as a seamstress. I just mention this to show what kind of father Mr. Dorrit is.

The next day, Amy wends her way to the Casby place, where she makes Flora’s acquaintance – Mr. F.’s Aunt having been wisely got out of the way – and where, first of all, she is offered some breakfast, along with a plethora of scattered observations and remarks by Flora. But also here, in Flora’s starkly romanticized account of how Arthur and she were torn asunder by an unrelenting Mrs. Clennam, an account to which she would invariably treat this newcomer, one can sense that at the bottom of it, there is real sorrow and despair. And the brandy Flora has with her breakfast – following the advice of her medical man, of course – just fits into the picture.

The chapter can, in a way, be quickly summarized as most of it renders Flora’s extensive explanations of Clennam’s and her situation, explanations which could give Amy some kind of wrong idea about Arthur’s feelings for Flora. When Flora finally leaves Amy to her work, Pancks appears on the scene, and he presents himself as a fortune-teller by way of palm-reading. While Pancks is reading out aloud some information on Amy’s family in order to gain her interest and confidence, let me just quote from Ambrose Bierce’s inimitable Devil’s Dictionary on the subject of palmistry:

”PALMISTRY, n. The 947th method (according to Mimbleshaw's classification) of obtaining money by false pretences. It consists in ‘reading character’ in the wrinkles made by closing the hand. The

pretence is not altogether false; character can really be read very accurately in this way, for the wrinkles in every hand submitted plainly spell the word ‘dupe.’ The imposture consists in not reading

it aloud.“

After reading in Amy’s palm, Pancks promises that maybe he will be able to read something more that might be of great use to her, but that time alone will tell. From that moment, Amy has yet another stalker about her in that Mr. Pancks will now frequently cross her path – not only at the Casbys’ but also on her ways about town and even within the confines of the Marshalsea prison, where he seems to be good friends with some of the inmates. Even Tip is now apparently of boon companion of Mr. Pancks’s.

It is quite obvious that this development might readily unsettle Amy a little bit. The chapter ends with Little Dorrit in her inornate – whatever embellishment she was able to afford she put up in her father’s room – yet tidy and clean garret, where she tells Maggy a kind of fairy-tale about a little woman who keeps the shadow of a dear person that has died. Maybe, this tale bears some reference to the story or to Amy’s own situation? It might also be important to mention that this evening Amy declines to see Mr. Clennam, who is visiting her father, on the grounds of not feeling too well. It is also typical that Clennam, possessive do-gooder that he is with regard to Amy, does not get the hint and already wants to send up a doctor. I mean a normal person would have realized that “not feeling well” might stand for “wanting some peace and quiet”, wouldn’t they?

In the narrator’s own words the state of mind Amy is in after spotting Pancks everywhere becomes admirably clear:

”Little Dorrit worked and strove as usual, wondering at all this, but keeping her wonder, as she had from her earliest years kept many heavier loads, in her own breast. A change had stolen, and was stealing yet, over the patient heart. Every day found her something more retiring than the day before. To pass in and out of the prison unnoticed, and elsewhere to be overlooked and forgotten, were, for herself, her chief desires.”

This week’s last Chapter is named “Conspirators and Others”, and although this may sound fishy at first, we may safely assume that the conspiracy described here will probably serve some good end. The action is set in Mr. Pancks’s lodgings and we also get to know Mr. Pancks’s landlord Mr. Rugg as well as Mr. Rugg’s daughter Anastatia. Mr. Rugg is, as his sign says, a general agent, an accountant and a debt-collector, and his daughter has achieved a not uncommon degree in notoriety in the neighbourhood because she sued a baker on the grounds of having proposed marriage to her and then backed out of it. This reminded me a bit of Mr. Pickwick’s landlady, but we might assume that in the case of Miss Rugg there was some kind of calculation involved. It’s definitely not for nothing that the narrator remarks that Mr. Rugg

This week’s last Chapter is named “Conspirators and Others”, and although this may sound fishy at first, we may safely assume that the conspiracy described here will probably serve some good end. The action is set in Mr. Pancks’s lodgings and we also get to know Mr. Pancks’s landlord Mr. Rugg as well as Mr. Rugg’s daughter Anastatia. Mr. Rugg is, as his sign says, a general agent, an accountant and a debt-collector, and his daughter has achieved a not uncommon degree in notoriety in the neighbourhood because she sued a baker on the grounds of having proposed marriage to her and then backed out of it. This reminded me a bit of Mr. Pickwick’s landlady, but we might assume that in the case of Miss Rugg there was some kind of calculation involved. It’s definitely not for nothing that the narrator remarks that Mr. Rugg”had a round white visage, as if all his blushes had been drawn out of him long ago”.

The Ruggs will not be done injustice if we assume that they know well which side their bread is buttered on – and yet it can be noted that Mr. Pancks is on easy terms with Miss Rugg and fears not in the least that he may share the baker’s fate. But then Mr. Pancks is also undaunted in the presence of Mr. F.’s Aunt, and he knows how to mollify her. Good old Mr. Pancks!

We learn that of late, since he became a fortune-teller, Mr. Pancks is more often in his lodgings, where he spends some nights in conference with Mr. Rugg, and that he has also won the confidence of the Chiverys. In fact, he sends Young John on certain errands from time to time, and although these errands may take him from his hearth for several days, Mrs. Chivery is quite pleased with this in that Young John’s despondency has diminished.

The bulk of the chapter brings us into one of the secret meetings of Mr. Pancks, Mr. Rugg and Young John, during which Mr. Pancks seems to distribute certain investigation tasks among them:

”’Now, there's a churchyard in Bedfordshire,’ said Pancks. ‘Who takes it?’

‘I'll take it, sir,’ returned Mr Rugg, ‘if no one bids.’

Mr Pancks dealt him his card, and looked at his hand again.

‘Now, there's an Enquiry in York,’ said Pancks. ‘Who takes it?’

‘I'm not good for York,’ said Mr Rugg.

‘Then perhaps,’ pursued Pancks, 'you'll be so obliging, John Chivery?’

Young John assenting, Pancks dealt him his card, and consulted his hand again.

‘There's a Church in London; I may as well take that. And a Family Bible; I may as well take that, too. That's two to me. Two to me,’ repeated Pancks, breathing hard over his cards. ‘Here's a Clerk at Durham for you, John, and an old seafaring gentleman at Dunstable for you, Mr Rugg. Two to me, was it? Yes, two to me. Here's a Stone; three to me. And a Still-born Baby; four to me. And all, for the present, told.’”

All this sounds very mysterious, and Young John arouses Mr. Panck’s genuine sympathy (along with slight contempt on the part of the Ruggs) by the following sentiment he divulges:

”’I can only assure you, Mr Pancks,’ said Young John, ‘that I deeply regret my circumstances being such that I can't afford to pay my own charges, or that it's not advisable to allow me the time necessary for my doing the distances on foot; because nothing would give me greater satisfaction than to walk myself off my legs without fee or reward.’”

Poor John Chivery! Having settled the business as to who is going to do what research, Mr. Pancks goes and sees the Italian traveller that Mr. Clennam has placed with the Plornish family, where Mrs. Plornish, in her own way, does the translating and has acquired quite a reputation of being fluent in something that is next to Italian itself. The narrator also comments on the spirit of helpfulness amongst those poor people:

”However, the Bleeding Hearts were kind hearts; and when they saw the little fellow cheerily limping about with a good-humoured face, doing no harm, drawing no knives, committing no outrageous immoralities, living chiefly on farinaceous and milk diet, and playing with Mrs Plornish's children of an evening, they began to think that although he could never hope to be an Englishman, still it would be hard to visit that affliction on his head.”

We may be sure that Signore Cavalletto is going to play some role or other in the course of events and that there will be many surprises for us until this wonderful book has come to its end.

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Pancks goes and sees the Italian traveller that Mr. Clennam has placed with the Plornish family, where Mrs. Plornish, in her own way, does the translating... "

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Pancks goes and sees the Italian traveller that Mr. Clennam has placed with the Plornish family, where Mrs. Plornish, in her own way, does the translating... "I apologize for not having any significant insights, observations, or even questions, but I just couldn't let this pass without saying that the Plornishes - like the Fezziwigs, the Boffins, and (to a lesser extent) the Bagnets - are among my favorite Dickens families. Poor, but so happy and good-hearted. I like to think that Dickens was drawing from happy times with Catherine and his young family before things went downhill.

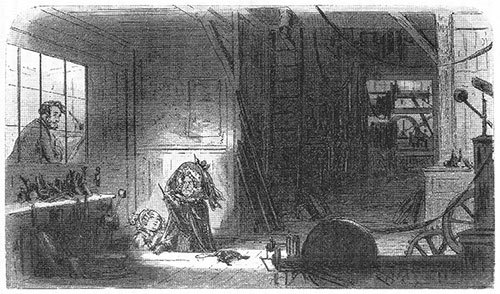

Here is the first illustration by Phiz for this installment:

Here is the first illustration by Phiz for this installment:

"Visitors at the Works"

Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated

"The little counting-house reserved for his own occupation, was a room of wood and glass at the end of a long low workshop, filled with benches, and vices, and tools, and straps, and wheels; which, when they were in gear with the steam-engine, went tearing round as though they had a suicidal mission to grind the business to dust and tear the factory to pieces. A communication of great trap-doors in the floor and roof with the workshop above and the workshop below, made a shaft of light in this perspective, which brought to Clennam's mind the child's old picture-book, where similar rays were the witnesses of Abel's murder. The noises were sufficiently removed and shut out from the counting-house to blend into a busy hum, interspersed with periodical clinks and thumps. The patient figures at work were swarthy with the filings of iron and steel that danced on every bench and bubbled up through every chink in the planking. The workshop was arrived at by a step-ladder from the outer yard below, where it served as a shelter for the large grindstone where tools were sharpened. The whole had at once a fanciful and practical air in Clennam's eyes, which was a welcome change; and, as often as he raised them from his first work of getting the array of business documents into perfect order, he glanced at these things with a feeling of pleasure in his pursuit that was new to him.

Raising his eyes thus one day, he was surprised to see a bonnet labouring up the step-ladder. The unusual apparition was followed by another bonnet. He then perceived that the first bonnet was on the head of Mr. F.'s Aunt, and that the second bonnet was on the head of Flora, who seemed to have propelled her legacy up the steep ascent with considerable difficulty. Though not altogether enraptured at the sight of these visitors, Clennam lost no time in opening the counting-house door, and extricating them from the workshop; a rescue which was rendered the more necessary by Mr. F.'s Aunt already stumbling over some impediment, and menacing steam power as an Institution with a stony reticule she carried.

"Good gracious, Arthur, — I should say Mr. Clennam, far more proper — the climb we have had to get up here and how ever to get down again without a fire-escape and Mr F.'s Aunt slipping through the steps and bruised all over and you in the machinery and foundry way too only think, and never told us!"

Thus, Flora, out of breath. Meanwhile, Mr. F.'s Aunt rubbed her esteemed insteps with her umbrella, and vindictively glared."

Commentary:

"Having settled into his small counting-house that looks out of the second story of the factory in Bleeding Heart Yard, Arthur Clennam is surprised by a visit from the dour Mr. F's Aunt and her jovial companion, the bubbly widow Flora Finching. The elderly lady emerges through the trapdoor with a look of disgust, while Flora, immediately below her, seems to be enjoying the experience of visiting Arthur in his place of work. However, Dickens's metonymy of the rising "bonnets," obvious in Phiz's illustration for both women, implies that such visitors are wholly inappropriate; even the enlightened Clennam is "not altogether enraptured at the sight of these visitors" as they constitute an unwarranted interruption in his putting the business's documents in working order. The bonnets, therefore, constitute an antiphonal symbol of domesticity in contradiction to the dominant images of machinery and foundry.

If Mr. Doyce represents "uncommon sense," the intelligence of the engineer and innovator, Arthur as the accountant and man of good business practices represents "common sense." His counting-house, therefore, is very much an accounting office where, pen in hand (as suggested by the inkwell and the quill pen), he has straightened out the books of the firm in which, weeks earlier, he has purchased a joint interest. Phiz's picture clearly delineates the level above the factory floor, but does not indicate precisely what kind of industrial activity transpires on this level of the building in Bleeding Heart Yard."

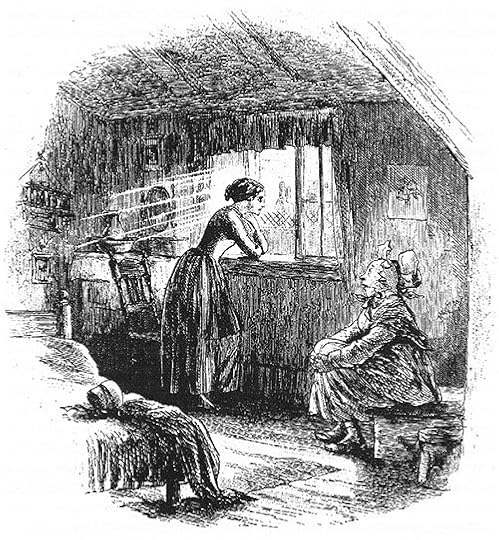

And this is the second illustration for this week:

And this is the second illustration for this week:

"The Story of the Princess"

Chapter 24

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"But it's all over now — all over for good, Maggy. And my head is much better and cooler, and I am quite comfortable. I am very glad I did not go down."

Her great staring child tenderly embraced her; and having smoothed her hair, and bathed her forehead and eyes with cold water (offices in which her awkward hands became skilful), hugged her again, exulted in her brighter looks, and stationed her in her chair by the window. Over against this chair, Maggy, with apoplectic exertions that were not at all required, dragged the box which was her seat on story-telling occasions, sat down upon it, hugged her own knees, and said, with a voracious appetite for stories, and with widely-opened eyes:

"Now, Little Mother, let's have a good 'un!"

"What shall it be about, Maggy?"

"Oh, let's have a princess," said Maggy, "and let her be a reg'lar one. Beyond all belief, you know!"

Little Dorrit considered for a moment; and with a rather sad smile upon her face, which was flushed by the sunset, began:

"Maggy, there was once upon a time a fine King, and he had everything he could wish for, and a great deal more. He had gold and silver, diamonds and rubies, riches of every kind. He had palaces, and he had —"

"Hospitals," interposed Maggy, still nursing her knees. "Let him have hospitals, because they're so comfortable. Hospitals with lots of Chicking."

"Yes, he had plenty of them, and he had plenty of everything."

"Plenty of baked potatoes, for instance?" said Maggy.

"Plenty of everything."

"Lor!" chuckled Maggy, giving her knees a hug. "Wasn't it prime!"

"This King had a daughter, who was the wisest and most beautiful Princess that ever was seen. When she was a child she understood all her lessons before her masters taught them to her; and when she was grown up, she was the wonder of the world. Now, near the Palace where this Princess lived, there was a cottage in which there was a poor little tiny woman, who lived all alone by herself."

Commentary:

"Phiz has portrayed Amy in such a way that she conveys the sense of an innocence so strong as to be impervious to the corruptions of either the Marshalsea or Society; this is less true of her figure in the cover design, where her character has not yet been established and she looks as if she is bowed down with resignation.

The scene seems prosaic enough: Little Dorrit's garret in the Marshalsea — "beautifully kept" and spotlessly clean, but otherwise as ugly as any other garret in the debtors' prison. Phiz complements the text by sharply realising the details of Amy's garret, but does not embed any symbolic elements — with the exception of the rays of sunlight that penetrate and illuminate her bedroom. If this plate exemplifies the story which Little Dorrit tells Maggy (right), the posture of the heroine at the window may suggest fairy-tale princesses trapped in towers, doomed to look upon life, but, like Tennyson's Lady of Shallot, cursed to remain above it, and never to interact with it.

Phiz depicts the room not merely as neat, but as an extension of Amy herself, with curtains on the window, a tidy bed — altogether a different effect from the rooms that Mr. Pickwick visits in the debtors' prison. Maggy, the mentally challenged young woman who is Amy's constant companion, child-like hugs her knees as she proposes Amy "tell us a good 'un." Wistfully, but with a concentrated look of determination, Amy looks below, to the College yard, rather than across the chimney pots and roofs to greater London.

Viewed as a complementary illustration to the dark plate Visitors at the Works, the other engraving in the seventh monthly number (June 1856) which presents Arthur Clennam's professional and personal progress as the business and accounting partner in the industrial enterprise Doyce and Clennam, The Story of the Princess reminds the reader of Amy Dorrit's lack of progress as she is a prisoner of the Marshalsea whether she plies her needle for wages or acts as an occasional servant outside the prison walls. Whereas Clennam in his business retreat works by artificial light on the second floor of a factory with little leisure time, Amy occupies a tiny garret and hopes for more out of life than she has received so far."

This is an illustration by James Mahoney:

This is an illustration by James Mahoney:

"What nimble fingers you have," said Flora, "but are you sure you are well?" . . . "Oh yes, indeed!" Flora put her feet upon the fender and settled herself for a thorough good romantic disclosure."

Book I, Chapter 24

James Mahoney

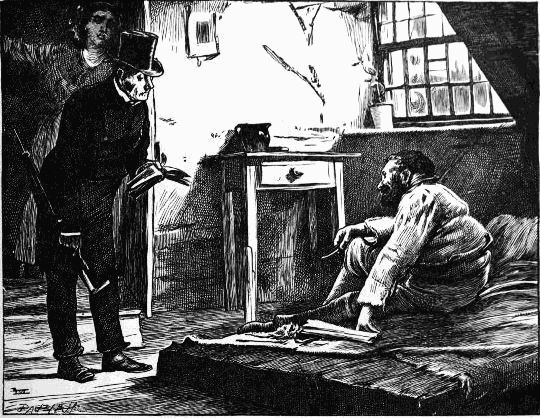

Another by James Mahoney:

Another by James Mahoney:

"Mounting to his attic, attended by Mrs. Plornish as interpreter, he found Mr. Baptist with no furniture but his bed on the ground, a table and a chair, carving with the aid of a few simple tools, in the blithest way possible. "Now, old chap," said Mr. Pancks, "pay up!"

Book I, Chapter 25

James Mahoney

This next illustration is by Harry Furniss:

This next illustration is by Harry Furniss:

"Little Dorrit tells The Story of the Princess:

Book I, Chapter 24

Commentary:

"In Furniss's redrafting, Amy is not looking despondently out of the window at the tawdry life of the College Yard, but is fully engaged in formulating the fairy story (a fictionalized and symbolic account of herself) that she is about to narrate for Maggy's entertainment in her upper-story garret in the Marshalsea. Furniss gives the reader little sense of the tidy nature of Amy's cramped room, focusing instead upon the physical differences between the large-headed, wide-eyed, cartoon-like Maggy and the sharply defined, realistically drawn Amy."

Kim wrote: "The Story of the Princess" Phiz

Kim wrote: "The Story of the Princess" PhizThis, and the Furniss illustration of the same scene, are the first illustrations of Amy, I believe, that have her looking like an actual woman, instead of Thumbelina. Even though I never cared for that scene (nor do I care for dream sequences - I'll have to delve into the reasons for that bias sometime), I appreciate these drawings for that reason.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Mr. Pancks goes and sees the Italian traveller that Mr. Clennam has placed with the Plornish family, where Mrs. Plornish, in her own way, does the translating... "

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Mr. Pancks goes and sees the Italian traveller that Mr. Clennam has placed with the Plornish family, where Mrs. Plornish, in her own way, does the translating... "I apologize for..."

I feel the same way, Mary Lou: This week's chapters did not really offer a lot of hooks but were mainly used, apparently, to connect Pancks and the Dorrits. Still, this fairy tale intrigued me, and I still don't know how to figure it out. Who is the Princess? The poor lonesome maid seems to be Little Dorrit, and the shadow, could it be Clennam? After all, we are told that Amy has taken up going to the Iron Bridge lately, and whom would she be thinking of there? But then, it's always tricky to make head or tail of a fairy tale.

Kim wrote: "However, Dickens's metonymy of the rising "bonnets," obvious in Phiz's illustration for both women, implies that such visitors are wholly inappropriate; even the enlightened Clennam is "not altogether enraptured at the sight of these visitors" as they constitute an unwarranted interruption in his putting the business's documents in working order. The bonnets, therefore, constitute an antiphonal symbol of domesticity in contradiction to the dominant images of machinery and foundry."

Kim wrote: "However, Dickens's metonymy of the rising "bonnets," obvious in Phiz's illustration for both women, implies that such visitors are wholly inappropriate; even the enlightened Clennam is "not altogether enraptured at the sight of these visitors" as they constitute an unwarranted interruption in his putting the business's documents in working order. The bonnets, therefore, constitute an antiphonal symbol of domesticity in contradiction to the dominant images of machinery and foundry."Again, I rather dislike the narrator for putting it like this: After all, Clennam, with a little bit of empathy, could have known that his re-appearance in Flora's life might contribute to lighting it up a bit and therefore, he could have found it in himself to pay her an occasional visit out of politeness and consideration. He is quite happy to fall back on Flora when he can put her services to use for Little Dorrit, and so I think he had better pay a bit more respect to Flora.

I really like the facial expression of Mr. F.'s Aunt, though.

Kim wrote: "This next illustration is by Harry Furniss:

Kim wrote: "This next illustration is by Harry Furniss:"Little Dorrit tells The Story of the Princess:

Book I, Chapter 24

Commentary:

"In Furniss's redrafting, Amy is not looking despondently out of the..."

I really like that illustration as much as Phiz's famous "original". Just look at how Maggy clasps her knee with both hands as someone who is absolutely riveted by an interesting story. I also like the idea that Amy is facing Maggy while telling the story.

Kim wrote: "And this is the second illustration for this week:

Kim wrote: "And this is the second illustration for this week:"The Story of the Princess"

Chapter 24

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"But it's all over now — all over for good, Maggy. And my head is much better..."

Kim, as always, thanks for the illustrations.

The Phiz illustration of "The Story of the Princess" illustrates an Amy Dorrit that looks like an adult. To me, there is a gentle strength to the illustration. Amy, the child who is the woman and Maggy, the woman who is a child are together in the Marshalsea. Both are imprisioned in many ways such as within a cell in a jail, a society that they have no easy access to, expectations for success that may never appear, a world that does not acknowledge their presence, and, perhaps most painfully, within a reality that they can only escape from by spinning fairy tales through their minds as they look out onto the outer walls of their room.

In the bottom left of the illustration we have a bonnet and cloak resting on the bed. I think this is suggestive of the shapeless lives that Amy and Maggie now live. Will they be able to fulfill a more substantial role in their lives, beyond the walls of the Marshalsea?

Powerful stuff.

With the presence of Daniel Doyce Dickens gives us a positive portrait of a man of skill and innovation within the emerging 19C. Just as Rouncewell the industrialist in BH was portrayed in a positive light so is Doyce in this novel. That is quite the change from the vitriolic portraits of business and industry in HT.

With the presence of Daniel Doyce Dickens gives us a positive portrait of a man of skill and innovation within the emerging 19C. Just as Rouncewell the industrialist in BH was portrayed in a positive light so is Doyce in this novel. That is quite the change from the vitriolic portraits of business and industry in HT.To me, it clearly proves that while Dickens may fondly recall the joys of the world of Mr. Pickwick, he also was attuned to the reality of the rapidly changing face of England during his lifetime. Just as change must and did come to Stagg's Gardens in DS, so there is hope and room for liberal and caring inventors and capitalists.

Tristram wrote: "Maybe it’s time for us to re-consider the roles of Mr. Casby and Mr. Pancks?"

Tristram wrote: "Maybe it’s time for us to re-consider the roles of Mr. Casby and Mr. Pancks?" Here is Kyd's idea of the Patriarch:

Peter wrote: "With the presence of Daniel Doyce Dickens gives us a positive portrait of a man of skill and innovation within the emerging 19C. Just as Rouncewell the industrialist in BH was portrayed in a positi..."

Peter wrote: "With the presence of Daniel Doyce Dickens gives us a positive portrait of a man of skill and innovation within the emerging 19C. Just as Rouncewell the industrialist in BH was portrayed in a positi..."Great post.

Peter wrote: "To me, it clearly proves that while Dickens may fondly recall the joys of the world of Mr. Pickwick, he also was attuned to the reality of the rapidly changing face of England during his lifetime. Just as change must and did come to Stagg's Gardens in DS, so there is hope and room for liberal and caring inventors and capitalists."

Peter wrote: "To me, it clearly proves that while Dickens may fondly recall the joys of the world of Mr. Pickwick, he also was attuned to the reality of the rapidly changing face of England during his lifetime. Just as change must and did come to Stagg's Gardens in DS, so there is hope and room for liberal and caring inventors and capitalists."I would like to second that, Peter! And I think that your last sentence is also borne out by Hard Times, namely when Stephen Blackpool says that it is not for the workers to unite and change things but for the factory owners and the government to do something about working conditions. Although I find it hard to agree with Dickens here, at least he is consistent.

Little Dorrit seems to me much more of a natural successor to Bleak House, rather than the very different "quickie" book Hard Times - brilliant though I think that was in demonstrating most of Dickens's extraordinary writing skills (except, necessarily, for his full-blown descriptive flights of fancy.)

Little Dorrit seems to me much more of a natural successor to Bleak House, rather than the very different "quickie" book Hard Times - brilliant though I think that was in demonstrating most of Dickens's extraordinary writing skills (except, necessarily, for his full-blown descriptive flights of fancy.)But I agree, we have a very sympathetic and fully rounded character in Daniel Doyce, the inventor. He seems eminently more intelligent and kind than Mr Meagles, and more akin to Mr Rouncewell. It's as if Dickens can only take on board both sides of industrial progress and encroachment if he has the space to do so. In a short novel, I think his views become more polarised.

Oh - I'm getting to really like the illustrations by Harry Furniss! Thanks Kim :) Of course nobody can top Phiz for caricature, but those by Harry Furniss are so good at creating atmosphere, and (shhhh - this is sacrilege!) I prefer them for the most dramatic scenes!

Jean wrote: "Little Dorrit seems to me much more of a natural successor to Bleak House, rather than the very different "quickie" book Hard Times - brilliant though I think ..."

Jean wrote: "Little Dorrit seems to me much more of a natural successor to Bleak House, rather than the very different "quickie" book Hard Times - brilliant though I think ..."Yes. Furniss is my second favourite after Browne too.

Books mentioned in this topic

Little Dorrit (other topics)Bleak House (other topics)

Hard Times (other topics)

Little Dorrit (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

More...

This week’s read gives yet another shove to the action, which can also be seen from the title of Chapter 23 – namely “Machinery in Motion”. All in all, it is a rather business-like and mechanical chapter because it is now that finally the partnership between Daniel Doyce and Arthur Clennam, under the auspices of Mr. Meagles, comes off. All this happens in an extremely meticulous way, with Daniel Doyce’s getting out of the way for a while in order to give Clennam the opportunity to take a very thorough look at the books and to consider whether he wants to enter into the partnership and also at what price. Although Clennam knows Daniel Doyce for a trustworthy and competent man, he still conscientiously dives into the matter of going through the books, and the upshot of it all is that Clennam values the partnership slightly more highly than the offer that Doyce expected.

The following days find Clennam hard at work in the counting-house of DOYCE AND CLENNAM, trying to get the whole of the business at his fingers’ ends, when one day, Flora and Mr. F.’s Aunt make their appearance in the counting-house. At first, Flora takes it rather ill that Clennam has never renewed his former visit and that it was through Pancks that she learned about his having entered business life in Bleeding Heart Yard. Words like the following may serve as a sign of how badly Clennam has actually hurt Flora’s feelings, for all her unnerving volubility:

”’I am very happy to see you,’ said Clennam, ‘and I thank you, Flora, very much for your kind remembrance.’

‘More than I can say myself at any rate,’ returned Flora, ‘for I might have been dead and buried twenty distinct times over and no doubt whatever should have been before you had genuinely remembered Me or anything like it in spite of which one last remark I wish to make, one last explanation I wish to offer—‘”

Eventually, however, her good nature gets the better of her, and she slowly, and with many excursions into their unhappy past, comes to the real point of her visit – her idea of employing Little Dorrit for doing needlework in her house, and it is here that Arthur’s interest suddenly flares up and he gladly takes Flora up on her word. In the course of their conversation, Mr. F.’s Aunt has made a rather hostile remark about there being milestones on the Dover road (maybe with the implication that Arthur go and count them), and the company is now added to by the arrival of Mr. Pancks and Mr. Casby himself. The latter exudes, as usual, a complacent atmosphere of serenity, and it is Pancks who acts as a kind of voice for him by explaining to Clennam that Casby never recommended Little Dorrit to Mrs. Clennam (for he could not do that, not having any knowledge of the quality of her services), but simply mentioned her name.

Mr. F.’s Aunt now adds more momentum to the situation by saying that

”’You can't make a head and brains out of a brass knob with nothing in it. You couldn't do it when your Uncle George was living; much less when he's dead.’”

All this clearly with reference to Arthur Clennam, and backed up by words that dare Clennam to “’chuck her out of winder’” if he wants her to leave. The situation is saved by the resourceful Pancks, who pretends to have just arrived on the scene and gallantly takes Mr. F.’s Aunt’s hand and leads her away, with Mr. Casby and Flora in their wake.

Nevertheless, Mr. Pancks returns after a short while, and to Clennam’s surprise he asks him to tell him all he knows about Little Dorrit. At first, Clennam is rather taken aback by the other person’s curiosity, which awakens suspicion in him, and here I could not help thinking that physicians should first of all try to heal themselves of things like unwonted curiosity with regard to strange people’s affairs, and poking their noses about, cross-examining turnkeys and prisoners. Nevertheless, when Pancks promises Clennam that he is not making the enquiry on behalf of Mr. Casby, whom he oddly refers to as his “proprietor”, and that his motive is good, Clennam imparts some knowledge as to Amy Dorrit’s circumstances to him.

The chapter ends with Mr. Pancks taking his leave and spreading terror among the inhabitants of the vicinity by collecting the rent. Most of his victims are of the opinion that Mr. Casby himself, a man of such reverend appearance, would never have gone so hard on them – but then the chapter ends like this:

”At which identical evening hour and minute, the Patriarch—who had floated serenely through the Yard in the forenoon before the harrying began, with the express design of getting up this trustfulness in his shining bumps and silken locks—at which identical hour and minute, that first-rate humbug of a thousand guns was heavily floundering in the little Dock of his exhausted Tug at home, and was saying, as he turned his thumbs:

‘A very bad day's work, Pancks, very bad day's work. It seems to me, sir, and I must insist on making this observation forcibly in justice to myself, that you ought to have got much more money, much more money.’”

Maybe it’s time for us to re-consider the roles of Mr. Casby and Mr. Pancks?