The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Great Expectations

Great Expectations

>

GE, Chapters 03-04

I just thought the whole Christmas Day dinner was hilarious but with purpose. My Grandmother used to tell me that children should be seen and not heard whenever I inserted my contrary self into a discussion at the dinner table, and I can't stop wondering if poor Pip hadn't been told that very same thing since he first moved into the Gargery home. It takes an army to save him.

I just thought the whole Christmas Day dinner was hilarious but with purpose. My Grandmother used to tell me that children should be seen and not heard whenever I inserted my contrary self into a discussion at the dinner table, and I can't stop wondering if poor Pip hadn't been told that very same thing since he first moved into the Gargery home. It takes an army to save him.

Pip's memory, and thus his perception, is certainly one of contrasts. On the one hand, there is little goodness or warmth between his sister and himself. Since his sister is 20 years his senior, obviously the assertive member of the family, and a rather harsh disciplinarian, there is little to connect Pip to his sister. On the other hand, Joe is initially presented as a person of compassion, concern and insight. He knows how to deal with his wife, accepts that there is little he can do to change her, and so he has adopted several coping strategies to help him and Pip survive her raising them both by hand. Pip finds himself in the middle of Joe and Mrs Joe and their vastly different parenting styles.

Pip's memory, and thus his perception, is certainly one of contrasts. On the one hand, there is little goodness or warmth between his sister and himself. Since his sister is 20 years his senior, obviously the assertive member of the family, and a rather harsh disciplinarian, there is little to connect Pip to his sister. On the other hand, Joe is initially presented as a person of compassion, concern and insight. He knows how to deal with his wife, accepts that there is little he can do to change her, and so he has adopted several coping strategies to help him and Pip survive her raising them both by hand. Pip finds himself in the middle of Joe and Mrs Joe and their vastly different parenting styles.

I found there to be a substantial change in how I read the convict in chapter 3. In the previous chapters, he comes of as gruff, menacing and depraved; whereas in this current chapter, in the presence of food, I could see how vulnerable the convict really is. This man was not menacing or depraved...Bless his heart, he was just "hangry (hunger->angry)!"

I found there to be a substantial change in how I read the convict in chapter 3. In the previous chapters, he comes of as gruff, menacing and depraved; whereas in this current chapter, in the presence of food, I could see how vulnerable the convict really is. This man was not menacing or depraved...Bless his heart, he was just "hangry (hunger->angry)!" Pip too notices a change in the convict's demeanor, or sees the humanity him while he's voraciously consuming all the wittles Pip has supplied. It was truly sad to see this man eating in a curious manner as Pip compares this sight to a dog's way of eating.

The dialogue too has changed, the convict being both gracious and thankful for Pip's help.

And what do you think of his, rather gentler, behaviour towards Pip on the occasion of their second meeting?

In answer to your question, Tristram...A "food swing" is probably the cause of the convict's gentler behavior.

I promise not to drone on every time there is an incidence of physical violence. That said, we see again in these early chapters more examples of violence. The convict eats "violently" and in "a violent hurry" and later in Chapter 3 the convict holds Pip such that "I began to think his first idea about cutting my throat had revived." Later in the chapter Pip tells the convict of the other man he saw on the marsh who "had a badly bruised face." To this description Pip's convict "[struck] his left cheek mercilessly, with the flat of his hand." In Chapter 4 Pumblechook tells Pip that the butcher would whip Pip and then "shed [Pip's] blood and had [his] life."

I promise not to drone on every time there is an incidence of physical violence. That said, we see again in these early chapters more examples of violence. The convict eats "violently" and in "a violent hurry" and later in Chapter 3 the convict holds Pip such that "I began to think his first idea about cutting my throat had revived." Later in the chapter Pip tells the convict of the other man he saw on the marsh who "had a badly bruised face." To this description Pip's convict "[struck] his left cheek mercilessly, with the flat of his hand." In Chapter 4 Pumblechook tells Pip that the butcher would whip Pip and then "shed [Pip's] blood and had [his] life." This troupe of violence seems to enfold both the characters and the plot so far in the novel. ... No spoilers, but keep an eye out for future incidents of physical violence in the novel.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I just thought the whole Christmas Day dinner was hilarious but with purpose. My Grandmother used to tell me that children should be seen and not heard whenever I inserted my contrary self into a d..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I just thought the whole Christmas Day dinner was hilarious but with purpose. My Grandmother used to tell me that children should be seen and not heard whenever I inserted my contrary self into a d..."Yes, I agree with this sentiment...I too found humor in the dinner dynamics while feeling terrible for Pip who is shoved in a corner, sitting between elbows and arms. It reminded me of the scene in David Copperfield when a very young David is traveling to the seaside in a carriage and essentially treated like a piece of luggage through the duration of the trip...It's as if he was not even there sitting among the adults since nobody made room for him.

Tristram wrote: "Hello again! In the second part of this week’s reading bit, I am going to summarize the next two chapters. In Chapter 3, Christmas Day Pip gets up very early and pilfers some “wittles” from the lar..."

Tristram wrote: "Hello again! In the second part of this week’s reading bit, I am going to summarize the next two chapters. In Chapter 3, Christmas Day Pip gets up very early and pilfers some “wittles” from the lar..."How are we made to participate in Pip’s anguish at having stolen the food from his sister’s pantry?

Oh, was this not a great moment in our reading? The anxiety riddled narration led to a frazzled reading experience, as I felt as if I was Pip enduring the e/motions of the evening. This poor child! :)

My favourite line from the novel so far is one that has been quoted many times before but how perfect is the description of the early Pip as "a bundle of shivers."

My favourite line from the novel so far is one that has been quoted many times before but how perfect is the description of the early Pip as "a bundle of shivers."

“dunghill as this poor wretched warmint is!"

“dunghill as this poor wretched warmint is!"Something clicked in his throat as if he had works in him like a clock, and was going to strike. And he smeared his ragged rough sleeve over his eyes.”

These lines struck me as marking the moment when the convict's opinion of Pip softens. Rubbing the eyes always suggests to me a tearing up, although I can't imagine the convict doing this. He does refer to himself as a poor wretched varmint, a mound of dung. Self pity? Just before he speaks thusly to Pip, the convict says, decides he believes Pip. He has just taken Pip's measure. Pip doesn't notice.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I just thought the whole Christmas Day dinner was hilarious but with purpose. My Grandmother used to tell me that children should be seen and not heard whenever I inserted my contrary self into a d..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I just thought the whole Christmas Day dinner was hilarious but with purpose. My Grandmother used to tell me that children should be seen and not heard whenever I inserted my contrary self into a d..."I agree entirely! My father's constant comment was, "What you want don't count." I like your comment on it taking an army to rescue poor Pip!

Ami wrote: "I found there to be a substantial change in how I read the convict in chapter 3. In the previous chapters, he comes of as gruff, menacing and depraved; whereas in this current chapter, in the prese..."

Ami wrote: "I found there to be a substantial change in how I read the convict in chapter 3. In the previous chapters, he comes of as gruff, menacing and depraved; whereas in this current chapter, in the prese..."Even in the introduction of the convict, while Pip obviously felt great fear and intimidation, I could not help but feel that the convict was "acting" for effect. It certainly worked because it made Pip fearful enough to challenge his sister's rule, however under the radar he tried to be. But even in the beginning, I think there was more hyperbole than actual threat in the convict. By the later chapters, we really begin to see him as a complex person who is not all bad.

The whole Christmas dinner is worth a re-read for me. Every time Pip has worked himself into a state fearing he is about to be caught, something happens to let him off the hook---I can just imagine the uncle getting ready to quaff his brandy and getting a dose of the tar-water instead and Mrs Joe being mystified as to how that could have happened, since she doesn't seem to even suspect Pip. The suspense builds, and then drops, and builds again, and then drops. I could actually feel Pip grabbing the chair leg and then relaxing a bit. Grabbing again and tensing up, and relaxing a bit. Until ultimately, the army and the convict get him of the hook completely. Whew!

The whole Christmas dinner is worth a re-read for me. Every time Pip has worked himself into a state fearing he is about to be caught, something happens to let him off the hook---I can just imagine the uncle getting ready to quaff his brandy and getting a dose of the tar-water instead and Mrs Joe being mystified as to how that could have happened, since she doesn't seem to even suspect Pip. The suspense builds, and then drops, and builds again, and then drops. I could actually feel Pip grabbing the chair leg and then relaxing a bit. Grabbing again and tensing up, and relaxing a bit. Until ultimately, the army and the convict get him of the hook completely. Whew!

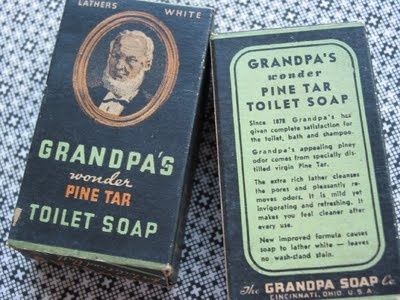

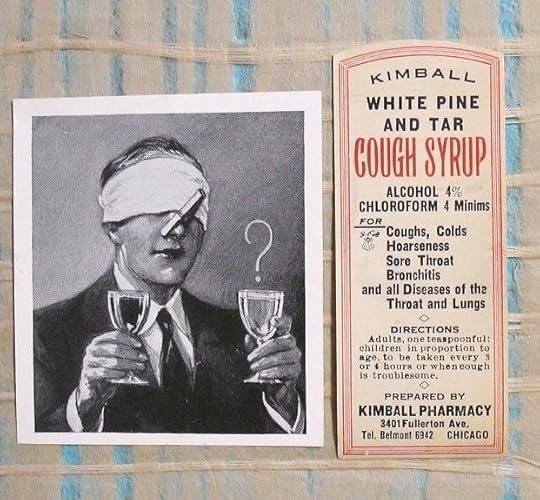

Tar-water--one of those terms that pops up in crossword puzzles from time to time, so I know kinda what it is. It was actually a medieval medicine that fell out of favor and for some reason became popular again with the Victorians. Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all. When gone, more water was poured in and stirred and allowed to sit again and drawn off. It was repeated until the resulting water was deemed too watered down to be of any use. It reminds me of sourdough starter--the starter is awful, but the bread is good. In the case of tar-water, it doesn't improve! Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin.

Tar-water--one of those terms that pops up in crossword puzzles from time to time, so I know kinda what it is. It was actually a medieval medicine that fell out of favor and for some reason became popular again with the Victorians. Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all. When gone, more water was poured in and stirred and allowed to sit again and drawn off. It was repeated until the resulting water was deemed too watered down to be of any use. It reminds me of sourdough starter--the starter is awful, but the bread is good. In the case of tar-water, it doesn't improve! Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin.

Lynne wrote: "Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all. ..."

Lynne wrote: "Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all. ..."Tar water and leeches. I wonder if any doctor ever prescribed the two together to cure what ails ya. Not grandma. Grandma was a castor oil gal through and through.

"You're not a false imp? You brought no one with you?"

Chapter 3

John McLenan

1860

Text Illustrated:

“I’ll eat my breakfast afore they’re the death of me,” said he. “I’d do that, if I was going to be strung up to that there gallows as there is over there, directly afterwards. I’ll beat the shivers so far, I’ll bet you.”

He was gobbling mincemeat, meatbone, bread, cheese, and pork pie, all at once: staring distrustfully while he did so at the mist all round us, and often stopping—even stopping his jaws—to listen. Some real or fancied sound, some clink upon the river or breathing of beast upon the marsh, now gave him a start, and he said, suddenly,—

“You’re not a deceiving imp? You brought no one with you?”

“No, sir! No!”

“Nor giv’ no one the office to follow you?”

“No!”

“Well,” said he, “I believe you. You’d be but a fierce young hound indeed, if at your time of life you could help to hunt a wretched warmint hunted as near death and dunghill as this poor wretched warmint is!”

Something clicked in his throat as if he had works in him like a clock, and was going to strike. And he smeared his ragged rough sleeve over his eyes.

But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman

John McLenan

Chapter 3

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I indicated in what direction the mist had shrouded the other man, and he looked up at it for an instant. But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman, and not minding me or minding his own leg, which had an old chafe upon it and was bloody, but which he handled as roughly as if it had no more feeling in it than the file. I was very much afraid of him again, now that he had worked himself into this fierce hurry, and I was likewise very much afraid of keeping away from home any longer. I told him I must go, but he took no notice, so I thought the best thing I could do was to slip off. The last I saw of him, his head was bent over his knee and he was working hard at his fetter, muttering impatient imprecations at it and at his leg. The last I heard of him, I stopped in the mist to listen, and the file was still going.

"Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!"

John McLenan

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I opened the door to the company,—making believe that it was a habit of ours to open that door,—and I opened it first to Mr. Wopsle, next to Mr. and Mrs. Hubble, and last of all to Uncle Pumblechook. N.B. I was not allowed to call him uncle, under the severest penalties.

“Mrs. Joe,” said Uncle Pumblechook, a large hard-breathing middle-aged slow man, with a mouth like a fish, dull staring eyes, and sandy hair standing upright on his head, so that he looked as if he had just been all but choked, and had that moment come to, “I have brought you as the compliments of the season—I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of sherry wine—and I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of port wine.”

Every Christmas Day he presented himself, as a profound novelty, with exactly the same words, and carrying the two bottles like dumb-bells. Every Christmas Day, Mrs. Joe replied, as she now replied, “O, Un—cle Pum-ble—chook! This is kind!” Every Christmas Day, he retorted, as he now retorted, “It’s no more than your merits. And now are you all bobbish, and how’s Sixpennorth of halfpence?” meaning me.

Pip Does Not Enjoy His Christmas Dinner

Chapter 4

Harry Furniss.

Dickens's Great Expectations, Charles Dickens Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

Among this good company I should have felt myself, even if I hadn't robbed the pantry, in a false position. Not because I was squeezed in at an acute angle of the table-cloth, with the table in my chest, and the Pumblechookian elbow in my eye, nor because I was not allowed to speak (I didn't want to speak), nor because I was regaled with the scaly tips of the drumsticks of the fowls, and with those obscure corners of pork of which the pig, when living, had had the least reason to be vain. No; I should not have minded that, if they would only have left me alone. But they wouldn't leave me alone. They seemed to think the opportunity lost, if they failed to point the conversation at me, every now and then, and stick the point into me. I might have been an unfortunate little bull in a Spanish arena, I got so smartingly touched up by these moral goads.

It began the moment we sat down to dinner. Mr. Wopsle said grace with theatrical declamation — as it now appears to me, something like a religious cross of the Ghost in Hamlet with Richard the Third — and ended with the very proper aspiration that we might be truly grateful. Upon which my sister fixed me with her eye, and said, in a low reproachful voice, "Do you hear that? Be grateful."

"Especially," said Mr. Pumblechook, "be grateful, boy, to them which brought you up by hand."

Mrs. Hubble shook her head, and contemplating me with a mournful presentiment that I should come to no good, asked, "Why is it that the young are never grateful?" This moral mystery seemed too much for the company until Mr. Hubble tersely solved it by saying, "Naterally wicious." Everybody then murmured "True!" and looked at me in a particularly unpleasant and personal manner.

Commentary:

Whereas the original Illustrated Library Edition and Household Edition illustrations do not reference this awkward moment in Pip's tense home-life, as he anticipates any moment being arrested for the theft of the pork pie and the file, Harry Furniss realizes most effectively this supremely comic passage which builds up to the consumption of the tar-water. Dickens's character comedy and social satire of the overreaching bourgeois Pumblechook and his theatrical companion, the village clerk and aspiring Shakespearean actor, Wopsle, appear in action, so to speak, rather than in a static portrait, as in Eytinge's illustration for the Diamond Edition.

Other illustrators have focused on the character comedy and social satire which the pompous, self-aggrandizing seed merchant Pumblechook presents throughout the early chapters, with McLenan and Pailthorpe both exaggerating his corpulence and complacency to contrast the lean, insecure Pip and his shrewish sister so effectively drawn by F. O. C. Darley in an early American piracy of the novel. Whereas other illustrators seem to have preferred scenes involving just a few characters, particularly interchanges between Pip and Magwitch and between Pip and Joe, in these opening chapters, Furniss depicts the oppressive social milieu in which Pip has grown up.

Furniss as an impressionistic illustrator attempts to convey (as so often the earlier illustrators do not) the acute discomfort, embarrassment, and terror that Pip feels as a child through the postures and expressions of Pumblechook (left) and the hawk-faced Wopsle (right of centre). In what we today would label a situation comedy, Furniss effectively translates the first-person reminiscence of the child-victim of the Christmas dinner, extreme right, between the bulk of the shock-haired Joe and the scowling visage and watchful gaze of his dictatorial sister; Furniss virtually dismisses the wheelwright, Mr. Hubble, as a non-entity, cramming him in behind Wopsle's outstretched arm, but showing the other adult diners as larger-than-life caricatures to give the reader a sense of the much-put-upon child's perspective.

One must read the illustration analytically, thumbing through the text to compare Dickens's handling of the scene and descriptions of the characters to sort out who is who. The "well-to-do corn chandler" is not a mere misshapen ogre with an enormous alcoholic nose and massive belly (as he is in McLenan); rather, Furniss characterizes him as large and domineering. Pailthorpe's corpulent Pumblechook (from a later scene) in May I — May I? comes closest to realising Dickens's comical description of Joe's prosperous relative as "a large, hard-breathing middle-aged slow man, with a mouth like a fish, dull staring eyes, and sandy hair standing upright on his head". Wopsle, on the other hand, is easily distinguished by his Roman nose and energetic gesticulation, his clothing suggesting the garb of an Anglican minister, although as clerk he is a mere lay-preacher and clergyman's assistant, and therefore does not wear a clerical collar.

Pumblechook and Wopsle

Sol Eytinge

Third illustration for Dickens's Great Expectations in A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations in the Ticknor & Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition.

Commentary:

In this third full-page dual character study for the second novel in the compact American publication, the parish clerk, Mr. Wopsle, yearns to be an actor, while "Uncle" Pumblechook —not, in fact, Mrs. Joe's uncle, but Joe's — is perfectly content with being a village seed merchant and the family's most successful connection, "a well-to-do corn-chandler" with his own "chaise-cart." According to Pip's descriptions of the pair in chapter 4, Pumblechook is a large-eyed, slow-moving, somewhat out-of-breath, fish-mouthed, sandy-haired, self-important humbug, while Mr. Wopsle has a theatrical air, a bald pate, and a Roman nose. Eytinge depicts them as the serious, balding, thin man, reading a book, and a contrasting fat man, both middle-aged.

The Harper's illustrator John McLenan provided Eytinge with a cartoon-like model of the corn merchant in "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!". However, McLenan does not bother to depict Wopsle at all in his forty woodcut illustrations. Given their relative positions at the table in Eytinge's illustration, the precise passage illustrated would seem to be this:

.......A little later on in the dinner, Mr. Wopsle reviewed the sermon with some severity, and intimated — in the usual hypothetical case of the Church being "thrown open" — what kind of sermon he would have given them. After favouring them with some heads of that discourse, he remarked that he considered the subject of the day's homily, ill-chosen; which was the less excusable, he added, when there were so many subjects 'going about.'

'True again,' said Uncle Pumblechook. 'You've hit it, sir! Plenty of subjects going about, for them that know how to put salt upon their tails. That's what's wanted. A man needn't go far to find a subject, if he's ready with his salt-box.' Mr. Pumblechook added, after a short interval of reflection, "Look at Pork alone. There's a subject! If you want a subject, look at Pork!'

'True, sir. Many a moral for the young,' returned Mr. Wopsle; and I knew he was going to lug me in, before he said it; 'might be deduced from that text.' [Chapter Four]

When authors are taught by circumstances that it is wiser for them to write serially, readers may be very sure that it is wiser for them to read serially. [Harper's Weekly, Nov., 1860]

But, then, of course the editors of the "American Journal of Civilization" would extol the virtues of serial reading since they were about to offer in spoonful's to the readers of Harper's Weekly a "New Story" from the hand of Britain's greatest living author. The illustrations created by the journal's house-artist, John McLenan, reveal his enthusiasm for the new story and his delight in Dickens's comic characters, such a welcome departure from the general seriousness of Little Dorrit and so much in the vein of the earlier works of the "Fielding of the Nineteenth Century," notably Pickwick. However, illustrating serially necessarily means creating in ignorance, for the illustrator if not in the confidence of the author (Phiz had such advance information, McLenan did not) cannot know whether a minor character such as Wopsle will occur again, acquiring a new significance, if not developing wholly. Such is the case with Wopsle in Great Expectations, for McLenan must have assumed that, like the Hubbles, fellow guests at the Gargerys' Christmas dinner, Wopsle was not worthy of visual realization — that he was simply stuffing for the moment when the tableful of guests assembled are shocked by Pip's substituting tar-water for brandy in the bottle from which Pumblechook has just taken a glass.

McLenan understandably regarded Pumblechook as a comic figure, depicting him as an obese bourgeois on spindly legs and carrying the signs of his economic superiority over the Gargerys, his annual offering of port and sherry. Like many of Dickens's lesser comic figures, Pumblechook behave so predictably as to be a human machine, and thereby becomes less than human, a mere platitude-making mechanism:

......."I have brought you as the compliments of the season — I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of sherry wine — and I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of port wine."

Every Christmas Day he presented himself, as a profound novelty, with exactly the same words, and carrying the two bottles like dumb-bells. Every Christmas Day, Mrs. Joe replied, as she now replied, "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!" [Chapter 4]

This was, in fact, the very moment which McLenan chose for realization at the head of the novel's second installment: a thin, almost skeletal Mrs. Joe greeting the Humpty-Dumpty figure of the corn merchant at the door. McLenan undoubtedly realized Pumblechook's comic potential, and drew him accordingly — as a cartoon. Eytinge, on the other hand, would have known to what ends both Pumblechook and Wopsle come later in the novel, probably having read and re-read the 1861 novel before completing his 1867 Diamond Edition commission to illustrate it in the new, "Sixties" manner, with modeled, three-dimensional figures and a more realistic handling.

Sorry, that's all the commentary you are getting, it tells us about things we certainly don't want to know, not yet anyway.

And we wouldn't want to miss an illustration by Kyd:

And we wouldn't want to miss an illustration by Kyd:

"Mr. Pumblechook"

J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd")

Watercolour

c. 1900

Kim wrote: "Pip Does Not Enjoy His Christmas Dinner

Kim wrote: "Pip Does Not Enjoy His Christmas Dinner Chapter 4

Harry Furniss.

Dickens's Great Expectations, Charles Dickens Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

Among this good company I should have felt mys..."

Thank you Kim. You keep us all "in the picture." Again, I think Furniss captures not only the event, but the emotion of the event. There is action and dynamics in his work.

Kim wrote: "And we wouldn't want to miss an illustration by Kyd:

Kim wrote: "And we wouldn't want to miss an illustration by Kyd:"Mr. Pumblechook"

J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd")

Watercolour

c. 1900"

Ah, Kyd. Just when I thought it was safe to go into the water again.

Kim wrote: "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!"

Kim wrote: "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!"That illustration of Pumblechook is just perfect. Thanks, Kim.

Ami wrote: "It reminded me of the scene in David Copperfield when a very young David is traveling to the seaside in a carriage and essentially treated like a piece of luggage through the duration of the trip...It's as if he was not even there sitting among the adults since nobody made room for him."

Ami wrote: "It reminded me of the scene in David Copperfield when a very young David is traveling to the seaside in a carriage and essentially treated like a piece of luggage through the duration of the trip...It's as if he was not even there sitting among the adults since nobody made room for him."Another great scene from David Copperfield comes into my mind - namely the dinner David has at the inn - in London? - where the waiter tricks him out of the lion's share of his meal. We learn that Pip is mostly given "the scaly tips of the drumsticks of the fowls, and [...] those obscure corners of pork of which the pig, when living, had had the least reason to be vain." I had to laugh out loud when I read the last bit of that sentence, and, again, I was in that favourite café of mine, it being Monday, and some people cast strange glances at me.

Lynne wrote: "Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all."

Lynne wrote: "Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all."Isn't that called Bourbon nowadays? ;-)

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all. ..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Pine tar was stirred up with water and allowed to sit a few days, at which time the water was drawn off to be used as a general cure-all. ..."Tar water and leeches. I wonder if any ..."

It's probably a good remedy for malingerers.

I quite like Sol Eytinge's idea of Pumblechook and Wopsle: The latter seems to be full of distrust - just look at his large eye -, probably suspecting that the Church is not "thrown open" for the only reason of depriving him of the career that is due to his talents, and Uncle Pumblechook looks life a stuffed fish, full of himself.

I quite like Sol Eytinge's idea of Pumblechook and Wopsle: The latter seems to be full of distrust - just look at his large eye -, probably suspecting that the Church is not "thrown open" for the only reason of depriving him of the career that is due to his talents, and Uncle Pumblechook looks life a stuffed fish, full of himself.

Ami wrote: "I found there to be a substantial change in how I read the convict in chapter 3.

Ami wrote: "I found there to be a substantial change in how I read the convict in chapter 3.Nice point.

Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."

Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."Yes, I used to use pine tar soap. The stuff you get today is considerably watered down from the stuff I used to get from Beans in the 50s. Just like the tar-water. [g]

Kim wrote: ""Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!"

Kim wrote: ""Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!"John McLenan."

Yuck. Pumblechook looks like illustrations for Frog in The Wind and the Willows, and Mrs. Joe looks like an absolute witch. I don't see her as that, but more as a harried housewife burdened with this imp brother thrust unwillingly on her, and no children her own to soften her.

New word of the day for me: ague

New word of the day for me: agueFavorite quotes:

My sister having so much to do, was going to church vicariously; that is to say, Joe and I were going.

"The gluttony of swine is put before us, as an example to the young." (I thought this pretty well in him who had been praising up the pork for being so plump and juicy.)

"If you'd been born a squeaker--"

"He was, if ever a child was," said my sister, most emphatically.

"Well, but I mean a four-footed squeaker," said Mr. Pumblechook. "If you had been born such, would you have been here now? Not you--"

"Unless in that form," said Mr. Wopsle, nodding towards the dish.

So, I was wondering why Pip took the pork pie, it seems like something that would be missed quite easily. He should have stuck to the items he had already grabbed. Also, I don't understand how the tar water got into the stone bottle? Pip said that he put it there?

Finally, I'm confused by the appearance of soldiers about to put handcuffs on Pip. But I'm sure I will find out why soon enough.

I'm off to read everyone's posts now.

Ami wrote: "The dialogue too has changed, the convict being both gracious and thankful for Pip's help."

Ami wrote: "The dialogue too has changed, the convict being both gracious and thankful for Pip's help."Yes, my heart softened towards the convict when he thanked Pip for the food. I was not expecting that. His eating "like a dog" softened me too, knowing how desperately hungry he must be. Of course, I have no idea what he did in order to become a convict - is he a murderer or did he do something small and petty?

Ami wrote: "feeling terrible for Pip who is shoved in a corner, sitting between elbows and arms. It reminded me of the scene in David Copperfield when a very young David is traveling to the seaside in a carriage and essentially treated like a piece of luggage through the duration of the trip...It's as if he was not even there sitting among the adults since nobody made room for him. "

Ami wrote: "feeling terrible for Pip who is shoved in a corner, sitting between elbows and arms. It reminded me of the scene in David Copperfield when a very young David is traveling to the seaside in a carriage and essentially treated like a piece of luggage through the duration of the trip...It's as if he was not even there sitting among the adults since nobody made room for him. "Oh, good comparison Ami! I had forgotten about this aspect of David's trip.

The McLean illustrations are really great. I love the detailed shading.

The McLean illustrations are really great. I love the detailed shading.The Furniss illustration of Christmas dinner makes me happy that I was not dining at Mrs. Joe's house that evening! And even more happy not to be poor Pip. So much for a pleasant holiday dinner.

There's something not right with Eytinge's Pumblechook. His head is far too small for the breadth of his body.

Oh! And we get a Kyd illustration! At least Pumblechook looks like a male in this one. :)

Tristram wrote: "We learn that Pip is mostly given "the scaly tips of the drumsticks of the fowls, and [...] those obscure corners of pork of which the pig, when living, had had the least reason to be vain." I had to laugh out loud when I read the last bit of that sentence, and, again, I was in that favourite café of mine, it being Monday, and some people cast strange glances at me."

Tristram wrote: "We learn that Pip is mostly given "the scaly tips of the drumsticks of the fowls, and [...] those obscure corners of pork of which the pig, when living, had had the least reason to be vain." I had to laugh out loud when I read the last bit of that sentence, and, again, I was in that favourite café of mine, it being Monday, and some people cast strange glances at me."Ha ha! That was a great line. :)

Everyman wrote: "Yuck. Pumblechook looks like illustrations for Frog in The Wind and the Willows"

Everyman wrote: "Yuck. Pumblechook looks like illustrations for Frog in The Wind and the Willows"Oh, you're so right! Between a frog and a fish (as Tristram mentioned), I think we can a agree that Pumblechook is certainly no looker.

Linda wrote: "New word of the day for me: ague

Linda wrote: "New word of the day for me: agueFavorite quotes:

My sister having so much to do, was going to church vicariously; that is to say, Joe and I were going.

"The gluttony of swine is put before us, ..."

Yes, the Christmas dinner scene is brimming with Dickens's humour and his trick of letting the characters speak for themselves - which, in the case of Pumblechook and Wopsle, is not exactly flattering to themselves ;-)

Everyman wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."

Everyman wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."Yes, I used to use pine tar soap. The stuff you get today is considerably watere..."

I got my son-in-law some pine tar soap for his stocking last year (this wasn't a comment on his hygiene -- Santa usually stuffs our stockings with toothbrushes, lip balm, etc. Santa is practical to a fault, except for those scratch-offs.) I have a feeling the soap went straight in the dumpster, after they drove home with all the windows down! Some people have no sense of adventure.

Everyman wrote: " Pumblechook looks like illustrations for Frog in The Wind and the Willows, and Mrs. Joe looks like an absolute witch. I ..."

Everyman wrote: " Pumblechook looks like illustrations for Frog in The Wind and the Willows, and Mrs. Joe looks like an absolute witch. I ..."Mr. Toad was the first thing I thought of when I saw that illustration, which makes me like Uncle Pumblechook more than I might otherwise.

Linda wrote: "So, I was wondering why Pip took the pork pie, it seems like something that would be missed quite easily. He should have stuck to the items he had already grabbed. Also, I don't understand how the tar water got into the stone bottle? Pip said that he put it there?."

Linda wrote: "So, I was wondering why Pip took the pork pie, it seems like something that would be missed quite easily. He should have stuck to the items he had already grabbed. Also, I don't understand how the tar water got into the stone bottle? Pip said that he put it there?."His taking the pie is not very clever, all the less so as he says that it has been carefully stowed away "in a covered earthenware dish in a corner". He could have put two and two together and guessed that this was probably meant to be the choice bit for that afternoon's Christmas dinner but maybe his fears disabled him from thinking along these lines. He might also have wanted to choose something substantial for the convict, and especially for the menacing young man, hoping that pork pie would make him abstain from boy's hearts and livers for a while.

I don't know about the tar-water, either. Pip had prepared some Spanish-liquorice-Water in another bottle, and maybe with that he diluted the brandy.

As to the handcuffs, it will all become clear in the next chapter.

Linda wrote: "Favorite quotes:

Linda wrote: "Favorite quotes:My sister having so much to do, was going to church vicariously; that is to say, Joe and I were going."

Yes -- this one made me chuckle, too.

Mary Lou wrote: "Linda wrote: "Favorite quotes:

Mary Lou wrote: "Linda wrote: "Favorite quotes:My sister having so much to do, was going to church vicariously; that is to say, Joe and I were going."

Yes -- this one made me chuckle, too."

My mom used to do that all the time, she would tell us that no, she wasn't going to church she had too much to do getting the Sunday dinner ready (which was always burnt) but we would go in her place.

Everyman wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."

Everyman wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."Yes, I used to use pine tar soap. The stuff you get today is considerably watere..."

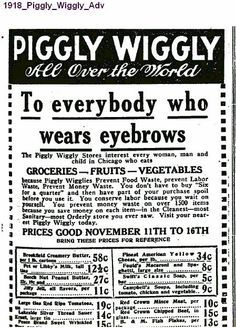

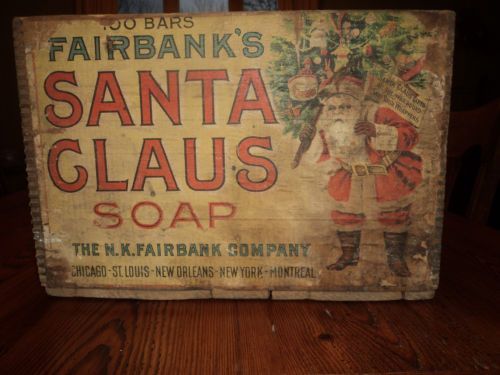

You have me thinking of pine tar soap and I went on a search, I found advertisements for the soap, but I loved some of the other ones too,

Kim wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."

Kim wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Lynne wrote: "Has anyone here ever used pinetar shampoo? Or soap? Pungent stuff, but good for the hair and skin. ."Yes, I used to use pine tar soap. The stuff you get today is co..."

Kim

I'm guessing the Santa soap is your favourite.

Tristram wrote: "Ami wrote: "It reminded me of the scene in David Copperfield when a very young David is traveling to the seaside in a carriage and essentially treated like a piece of luggage through the duration o..."

Tristram wrote: "Ami wrote: "It reminded me of the scene in David Copperfield when a very young David is traveling to the seaside in a carriage and essentially treated like a piece of luggage through the duration o..."Okay, you know what I was laughing out loud at here...Like you said, he was given the "scaly scraps," I couldn't understand what exactly it was Joe kept putting all that gravy on-Pip hardly had any food on his plate?! LOL!

Kim wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Linda wrote: "Favorite quotes:

Kim wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Linda wrote: "Favorite quotes:My sister having so much to do, was going to church vicariously; that is to say, Joe and I were going."

Yes -- this one made me chuckle, too."

My ..."

Oh, Kim. I am sitting here shaking my head at this...Burnt, "every" time? LOL!

When I was a kid I hated vegetables, so did my sister, the memories from our childhood eating experiences are still with her, she still hates vegetables. The kind you cook that is. I always loved tomatoes, and lettuce, and other kinds that people don't cook in a pan on the stove. They were all horrible. It didn't matter what the vegetable was they all tasted the same. Mom always put them on the table in a big bowl with all the "vegetable juice" in the bowl with them. We thought vegetable juice was awful, it was always brown and terrible tasting and it didn't matter if it was corn or peas or anything else they all came in that brown juice. The juice just came out of the vegetables when you cook them and ruin it, at least that's what we thought when we were kids. Then one day I grew up, tasted vegetables dishes other than what my mom made and they were wonderful. I then took over making the big meals - mom always hated doing it - and our vegetables were no longer in a brown juice which by then we had learned was what happened when she burnt them to the bottom of the pan then poured more water into the pan and scraped the vegetables off the bottom. We then had burnt vegetables in burnt vegetable juice.

When I was a kid I hated vegetables, so did my sister, the memories from our childhood eating experiences are still with her, she still hates vegetables. The kind you cook that is. I always loved tomatoes, and lettuce, and other kinds that people don't cook in a pan on the stove. They were all horrible. It didn't matter what the vegetable was they all tasted the same. Mom always put them on the table in a big bowl with all the "vegetable juice" in the bowl with them. We thought vegetable juice was awful, it was always brown and terrible tasting and it didn't matter if it was corn or peas or anything else they all came in that brown juice. The juice just came out of the vegetables when you cook them and ruin it, at least that's what we thought when we were kids. Then one day I grew up, tasted vegetables dishes other than what my mom made and they were wonderful. I then took over making the big meals - mom always hated doing it - and our vegetables were no longer in a brown juice which by then we had learned was what happened when she burnt them to the bottom of the pan then poured more water into the pan and scraped the vegetables off the bottom. We then had burnt vegetables in burnt vegetable juice.

Kim wrote: "When I was a kid I hated vegetables, so did my sister, the memories from our childhood eating experiences are still with her, she still hates vegetables. The kind you cook that is. I always loved t..."

Kim wrote: "When I was a kid I hated vegetables, so did my sister, the memories from our childhood eating experiences are still with her, she still hates vegetables. The kind you cook that is. I always loved t..."LOL! Oh myyy, you have to stop! This is the best thing I've read all day... You make it sound like moment from a Grimm's Fairy Tale! Dinner time, or at least those that included "brown vegetables," sounds horrific.

I'm really glad you eat your vegetables now in spite of Mom's culinary efforts.

Ah, great story... Thank you!

Ami wrote: " I couldn't understand what exactly it was Joe kept putting all that gravy on-He hardly had any food on his plate?! LOL!"

Ami wrote: " I couldn't understand what exactly it was Joe kept putting all that gravy on-He hardly had any food on his plate?! LOL!"Ha ha! In one instance didn't Joe ladle on a half-pint (or full pint?) of gravy? :D

In Chapter 4, we have some comic relief, largely at the expense of our protagonist, though, when Mrs. Joe and her husband entertain guests for Christmas. These guests are the parish clerk Mr. Wopsle, who seems to consider himself not yet in the social station that is due to him, Mr. and Mrs. Hubble, and Joe Gargery’s uncle Pumblechook, a well-to-do corn-chandler from the neighbouring cathedral town (i.e. probably Rochester),

During the dinner, all guests make very uncomplimentary remarks as to Pip in particular and young people in general, especially with regard to their ungratefulness – only Joe tries to make the situation better for Pip by ladling gravy on his plate. When the moment comes for Mrs. Joe to present the company with a piece of pork pie, the pork pie being a gift from Uncle Pumblechook, Pip’s heart sinks into his boots because the pork pie was amongst the victuals that he took to the convict. His theft will out now, and that’s why he bolts from the room and out of the door, were – he runs into a party of soldiers, one of them holding out a pair of handcuffs to him.

Some questions:

As before, what do you make of Mrs. Gargery? What might be her feelings for her younger brother in particular? Consider the following quotation:

Again, what do you think of the first perspective here? How are we made to participate in Pip’s anguish at having stolen the food from his sister’s pantry?

Why might the first convict react in such an infuriated way to the news that some other man has escaped from the Hulks? And what do you think of his, rather gentler, behaviour towards Pip on the occasion of their second meeting?

Have you any favourite quotations from the first four chapters? And what made you choose them?