The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 1, Chp. 14-17

Chapter 15 introduces us to “Two New Servants” in the Boffin household, one of them actually not being really new and in that top condition. The Chapter already starts in a way that puts things in a nutshell in a typically Dickensian manner – although there are some people, I’ve heard of them, that say that Dickens was a man of too many words.

Can the awkwardness of their new situation, being surrounding by unaccustomed wealth and unknown responsibilities, be summarized in a better way? No!

Like Pip and Herbert, one book ago, Mr Boffin is trying to do his accounts or whatever business papers he has to attend to, when he is interrupted by the arrival of Mr Rokesmith, who came to see whether Mr Boffin had already resolved on letting him enter his service. What a good opportunity for Mr Rokesmith to sit himself down and show his abilities as a Secretary by settling the papers over which Mr Boffin had been poring! By the way, apparently Mr Boffin has up to now always thought that a Secretary was inevitably a piece of furniture. I wonder whether this was an exclusive quirk of Mr Boffin’s or whether the term was generally unknown then with reference to people – because one chapter later, a similar misunderstanding arises in a conversation between Mr Rokesmith and Miss Wilfer.

After Rokesmith has completed his work, Mr Boffin agrees to employ him as his secretary, on the understanding that for an indefinite period of time he will not be paid any wages (as Rokesmith himself once suggested). This detail made me wonder, and I also think it a little bit inconsistent with Mr Boffin’s general inclination to generosity. Why should he take the chance of not paying any wages for services that are done to him? This does not sound at all like the Mr Boffin we have come to know so far. All the less so since Mr Boffin clearly evinces signs of great perturbation with regard to his other servant, the literary man WITH a wooden leg.

In the second part of this chapter, Mr Boffin tries his best to appease Mr Wegg lest any jealousy and animosity arise with regard to Mr Rokesmith, and he does it the following way: Since the Boffins now move to their new, more stately home, apparently the one Mr Wegg has been selling his ballads in front of, he now offers Wegg the position as a manager of the old house, formerly known as Harmon Jail, because Mr Boffin does not intend to sell it, whereas he might eventually make efforts to sell the dust mounds. Mr Wegg is greatly pleased with this new rise in his affairs, although in his cunning way, he makes sure that the salary connected with the new position will be paid to him in addition to the remunerations due to him for declining and falling every evening. The narrator is clearly in disfavour of Mr Wegg’s ability to look after himself, implying that he is a mean man:

Although our narrator seems to be prejudiced against Wegg, I must say that I rather like his presence in our chapter because he enlivens it with his ramshackle poetry and his cunning ways of doing business.

The conversation between Boffin and Wegg takes place in the old house, and we get another impression of how dismal and forsaken an old house it is. Just look at this quotation:

The only detail that shows some signs of gentleness, fond childhood memories and life is the place where the two Harmon children had made marks in the doorway when they were measured. The Boffins swear to themselves that they will do anything to keep these marks whatever may befall to the house.

The chapter ends with a little scene in which Mrs Boffin shows signs of extreme worry and fear, quite untypical of her, because she fancies she has seen several faces in the air – the children’s faces, the old man’s face, an unknown person’s face, and all rolled into one. Mr Boffin does his best to soothe her, and the chapter ends like this:

”Mr and Mrs Boffin sat after breakfast, in the Bower, a prey to prosperity.”

Can the awkwardness of their new situation, being surrounding by unaccustomed wealth and unknown responsibilities, be summarized in a better way? No!

Like Pip and Herbert, one book ago, Mr Boffin is trying to do his accounts or whatever business papers he has to attend to, when he is interrupted by the arrival of Mr Rokesmith, who came to see whether Mr Boffin had already resolved on letting him enter his service. What a good opportunity for Mr Rokesmith to sit himself down and show his abilities as a Secretary by settling the papers over which Mr Boffin had been poring! By the way, apparently Mr Boffin has up to now always thought that a Secretary was inevitably a piece of furniture. I wonder whether this was an exclusive quirk of Mr Boffin’s or whether the term was generally unknown then with reference to people – because one chapter later, a similar misunderstanding arises in a conversation between Mr Rokesmith and Miss Wilfer.

After Rokesmith has completed his work, Mr Boffin agrees to employ him as his secretary, on the understanding that for an indefinite period of time he will not be paid any wages (as Rokesmith himself once suggested). This detail made me wonder, and I also think it a little bit inconsistent with Mr Boffin’s general inclination to generosity. Why should he take the chance of not paying any wages for services that are done to him? This does not sound at all like the Mr Boffin we have come to know so far. All the less so since Mr Boffin clearly evinces signs of great perturbation with regard to his other servant, the literary man WITH a wooden leg.

In the second part of this chapter, Mr Boffin tries his best to appease Mr Wegg lest any jealousy and animosity arise with regard to Mr Rokesmith, and he does it the following way: Since the Boffins now move to their new, more stately home, apparently the one Mr Wegg has been selling his ballads in front of, he now offers Wegg the position as a manager of the old house, formerly known as Harmon Jail, because Mr Boffin does not intend to sell it, whereas he might eventually make efforts to sell the dust mounds. Mr Wegg is greatly pleased with this new rise in his affairs, although in his cunning way, he makes sure that the salary connected with the new position will be paid to him in addition to the remunerations due to him for declining and falling every evening. The narrator is clearly in disfavour of Mr Wegg’s ability to look after himself, implying that he is a mean man:

”The man of low cunning had, of course, acquired a mastery over the man of high simplicity. The mean man had, of course, got the better of the generous man. How long such conquests last, is another matter; that they are achieved, is every-day experience, not even to be flourished away by Podsnappery itself. The undesigning Boffin had become so far immeshed by the wily Wegg that his mind misgave him he was a very designing man indeed in purposing to do more for Wegg. It seemed to him (so skilful was Wegg) that he was plotting darkly, when he was contriving to do the very thing that Wegg was plotting to get him to do. And thus, while he was mentally turning the kindest of kind faces on Wegg this morning, he was not absolutely sure but that he might somehow deserve the charge of turning his back on him.“

Although our narrator seems to be prejudiced against Wegg, I must say that I rather like his presence in our chapter because he enlivens it with his ramshackle poetry and his cunning ways of doing business.

The conversation between Boffin and Wegg takes place in the old house, and we get another impression of how dismal and forsaken an old house it is. Just look at this quotation:

”A gloomy house the Bower, with sordid signs on it of having been, through its long existence as Harmony Jail, in miserly holding. Bare of paint, bare of paper on the walls, bare of furniture, bare of experience of human life. Whatever is built by man for man’s occupation, must, like natural creations, fulfil the intention of its existence, or soon perish. This old house had wasted—more from desuetude than it would have wasted from use, twenty years for one.

A certain leanness falls upon houses not sufficiently imbued with life (as if they were nourished upon it), which was very noticeable here. The staircase, balustrades, and rails, had a spare look—an air of being denuded to the bone—which the panels of the walls and the jambs of the doors and windows also bore. The scanty moveables partook of it; save for the cleanliness of the place, the dust—into which they were all resolving would have lain thick on the floors; and those, both in colour and in grain, were worn like old faces that had kept much alone.

The bedroom where the clutching old man had lost his grip on life, was left as he had left it. There was the old grisly four-post bedstead, without hangings, and with a jail-like upper rim of iron and spikes; and there was the old patch-work counterpane. There was the tight-clenched old bureau, receding atop like a bad and secret forehead; there was the cumbersome old table with twisted legs, at the bed-side; and there was the box upon it, in which the will had lain. A few old chairs with patch-work covers, under which the more precious stuff to be preserved had slowly lost its quality of colour without imparting pleasure to any eye, stood against the wall. A hard family likeness was on all these things.”

The only detail that shows some signs of gentleness, fond childhood memories and life is the place where the two Harmon children had made marks in the doorway when they were measured. The Boffins swear to themselves that they will do anything to keep these marks whatever may befall to the house.

The chapter ends with a little scene in which Mrs Boffin shows signs of extreme worry and fear, quite untypical of her, because she fancies she has seen several faces in the air – the children’s faces, the old man’s face, an unknown person’s face, and all rolled into one. Mr Boffin does his best to soothe her, and the chapter ends like this:

”Opening her eyes again, and seeing her husband’s face across the table, she leaned forward to give it a pat on the cheek, and sat down to supper, declaring it to be the best face in the world.”

Chapter 16 is all about “Minders and Re-Minders”, and we see the new secretary starting his job of settling Mr Boffin’s affairs, a task in the execution of which he shows great assiduity and skill and, above all, knowledge of the business and the will, so much so that a more distrustful person than Mr Boffin would have rubbed his chin and his nose and drawn conclusions as to sinister motives of the new employee. There is another strange thing about Mr Rokesmith, namely that whereas he is normally eager to please and never shirks a duty, he is not willing to have any personal contact with Mr Boffin’s lawyer Mortimer Lightwood. Do what he will, Mr Boffin simply cannot get him to pay a visit to Lightwood, and he offers a – what to me seems – rather lame excuse by saying that he prefers not to get in between a lawyer and his client. Apart from that, there is an odd impression about him, which I let the narrator himself explain:

Nevertheless, Rokesmith has no objection to writing to Lightwood, and so he writes him telling him that Mr Boffin, in the light of the new events concerning the Harmon murder, is ready to offer another reward for anyone who can produce the witness Julius Handford. Actually, Mr Boffin thinks that it will not be much use, and his secretary concurs – and the ensuing events, or rather the lack of them, will prove them right.

Mr Boffin also concentrates on another mission, namely the one of adopting a young orphan, one of the most urgent wishes of his wife. This is not so easy, however, since people actually start resorting to all sorts of fraudulent activities in order to make money out of the Boffins’s determination to do good. Since this strife for money by all means is one of the motifs of the book, and since the passage it quite funny, I’ll quote it here:

Eventually, the Milveys find a suitable orphan, though, and the Boffins pay a visit to the cottage where he and his grandmother, Betty Higden, a near-octogenarian who is still in comparatively good health, lives. The cottage is poor, but tidy, and the orphan is small and cute, and already has the name of Johnny, which is a good sign. Betty Higden also looks after three other kids, one of them a boy called Sloppy because he was found on a sloppy night, and she is very much afraid of the workhouse and determined never to go there. She even gives a passionate little speech:

This gives Dickens the opportunity of acting as an intrusive narrator and also adding his own thoughts about the Poor Law. The upshot of the visit at Betty Higden’s is that the Boffins would be charmed to have Johnny at their house, but that as yet Betty is not ready to part with him, this being the only family member still alive, and so the Boffins say they will wait a bit.

The chapter ends with a conversation between Rokesmith and Miss Bella on a chance encounter that has actually been provoked by Rokesmith. In the course of their conversation, which is finally interrupted by Mrs Wilfer, Rokesmith notices what kind of materialistic and fickle girl Bella is, but he can’t help admiring her:

Then he also adds something way more mysterious than that a man should be induced to overlook faults because of a woman’s beauty; he says, “And if she knew!”

Knew what?

”As on the Secretary’s face there was a nameless cloud, so on his manner there was a shadow equally indefinable. It was not that he was embarrassed, as on that first night with the Wilfer family; he was habitually unembarrassed now, and yet the something remained. It was not that his manner was bad, as on that occasion; it was now very good, as being modest, gracious, and ready. Yet the something never left it. It has been written of men who have undergone a cruel captivity, or who have passed through a terrible strait, or who in self-preservation have killed a defenceless fellow-creature, that the record thereof has never faded from their countenances until they died. Was there any such record here?”

Nevertheless, Rokesmith has no objection to writing to Lightwood, and so he writes him telling him that Mr Boffin, in the light of the new events concerning the Harmon murder, is ready to offer another reward for anyone who can produce the witness Julius Handford. Actually, Mr Boffin thinks that it will not be much use, and his secretary concurs – and the ensuing events, or rather the lack of them, will prove them right.

Mr Boffin also concentrates on another mission, namely the one of adopting a young orphan, one of the most urgent wishes of his wife. This is not so easy, however, since people actually start resorting to all sorts of fraudulent activities in order to make money out of the Boffins’s determination to do good. Since this strife for money by all means is one of the motifs of the book, and since the passage it quite funny, I’ll quote it here:

”Either an eligible orphan was of the wrong sex (which almost always happened) or was too old, or too young, or too sickly, or too dirty, or too much accustomed to the streets, or too likely to run away; or, it was found impossible to complete the philanthropic transaction without buying the orphan. For, the instant it became known that anybody wanted the orphan, up started some affectionate relative of the orphan who put a price upon the orphan’s head. The suddenness of an orphan’s rise in the market was not to be paralleled by the maddest records of the Stock Exchange. He would be at five thousand per cent discount out at nurse making a mud pie at nine in the morning, and (being inquired for) would go up to five thousand per cent premium before noon. The market was ‘rigged’ in various artful ways. Counterfeit stock got into circulation. Parents boldly represented themselves as dead, and brought their orphans with them. Genuine orphan-stock was surreptitiously withdrawn from the market. It being announced, by emissaries posted for the purpose, that Mr and Mrs Milvey were coming down the court, orphan scrip would be instantly concealed, and production refused, save on a condition usually stated by the brokers as ‘a gallon of beer’. Likewise, fluctuations of a wild and South-Sea nature were occasioned, by orphan-holders keeping back, and then rushing into the market a dozen together. But, the uniform principle at the root of all these various operations was bargain and sale; and that principle could not be recognized by Mr and Mrs Milvey.”

Eventually, the Milveys find a suitable orphan, though, and the Boffins pay a visit to the cottage where he and his grandmother, Betty Higden, a near-octogenarian who is still in comparatively good health, lives. The cottage is poor, but tidy, and the orphan is small and cute, and already has the name of Johnny, which is a good sign. Betty Higden also looks after three other kids, one of them a boy called Sloppy because he was found on a sloppy night, and she is very much afraid of the workhouse and determined never to go there. She even gives a passionate little speech:

”‘Dislike the mention of it?’ answered the old woman. ‘Kill me sooner than take me there. Throw this pretty child under cart-horses feet and a loaded waggon, sooner than take him there. Come to us and find us all a-dying, and set a light to us all where we lie and let us all blaze away with the house into a heap of cinders sooner than move a corpse of us there!’”

This gives Dickens the opportunity of acting as an intrusive narrator and also adding his own thoughts about the Poor Law. The upshot of the visit at Betty Higden’s is that the Boffins would be charmed to have Johnny at their house, but that as yet Betty is not ready to part with him, this being the only family member still alive, and so the Boffins say they will wait a bit.

The chapter ends with a conversation between Rokesmith and Miss Bella on a chance encounter that has actually been provoked by Rokesmith. In the course of their conversation, which is finally interrupted by Mrs Wilfer, Rokesmith notices what kind of materialistic and fickle girl Bella is, but he can’t help admiring her:

”‘So insolent, so trivial, so capricious, so mercenary, so careless, so hard to touch, so hard to turn!’ he said, bitterly.

And added as he went upstairs. ‘And yet so pretty, so pretty!’”

Then he also adds something way more mysterious than that a man should be induced to overlook faults because of a woman’s beauty; he says, “And if she knew!”

Knew what?

Chapter 17 concludes the first book and leads us into “A Dismal Swamp”. It’s a rather short chapter that tells us of “all manner of crawling, creeping, fluttering, and buzzing creatures, attracted by the gold dust of the Golden Dustman!”

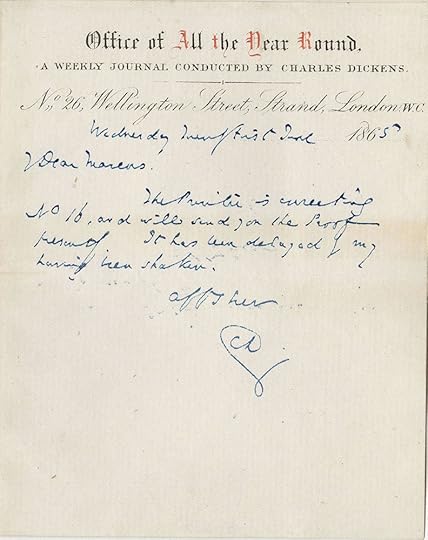

First of all, we learn how all the world and his wife leave their cards at the stately house of the Boffins, the Veneerings even before the paint on the front door has completely dried. We also get to know the amount of begging letters that have to be dealt with by Mr Rokesmith, all sorts of people who want to wheedle some money out of the newly-rich Boffin. Our narrator gives a hilarious account of the different strategies these beggars employ, and I couldn’t help thinking that maybe Dickens here wrote drawing from his own experience, because as a famous and successful writer he must have got basketfuls of such letters. Which set me thinking on how much time he might generally have spent reading and replying to his fan mail, or letters like that, and how he could have found the time to produce such an immense literary output still.

We also learn that Mr Wegg, down at the old house, is evidently also employed in searching for something particular:

Now, what might this paragon of selfless virtue, our Mr Wegg, be expecting to find there?

We have already finished the first book of the novel, which is called “The Cup and the Lip”. Obviously, this title refers to the old proverb, which brings us to the question of how many slips between cups and lips we have witnessed in the past few chapters … did anyone keep tabs on this?

First of all, we learn how all the world and his wife leave their cards at the stately house of the Boffins, the Veneerings even before the paint on the front door has completely dried. We also get to know the amount of begging letters that have to be dealt with by Mr Rokesmith, all sorts of people who want to wheedle some money out of the newly-rich Boffin. Our narrator gives a hilarious account of the different strategies these beggars employ, and I couldn’t help thinking that maybe Dickens here wrote drawing from his own experience, because as a famous and successful writer he must have got basketfuls of such letters. Which set me thinking on how much time he might generally have spent reading and replying to his fan mail, or letters like that, and how he could have found the time to produce such an immense literary output still.

We also learn that Mr Wegg, down at the old house, is evidently also employed in searching for something particular:

”For, when a man with a wooden leg lies prone on his stomach to peep under bedsteads; and hops up ladders, like some extinct bird, to survey the tops of presses and cupboards; and provides himself an iron rod which he is always poking and prodding into dust-mounds; the probability is that he expects to find something.”

Now, what might this paragon of selfless virtue, our Mr Wegg, be expecting to find there?

We have already finished the first book of the novel, which is called “The Cup and the Lip”. Obviously, this title refers to the old proverb, which brings us to the question of how many slips between cups and lips we have witnessed in the past few chapters … did anyone keep tabs on this?

Having started this section of chapters, just last night, my question is:

Having started this section of chapters, just last night, my question is:Who is supposed to be the main character of this novel?

Having also read these chapters last night, I am appreciative of your facility for summary, Tristram.

Having also read these chapters last night, I am appreciative of your facility for summary, Tristram.As to your question, John, wouldn't it be the title character?

Tristram wrote: " The Chapter already starts in a way that puts things in a nutshell in a typically Dickensian manner – although there are some people, I’ve heard of them, that say that Dickens was a man of too many words.

Tristram wrote: " The Chapter already starts in a way that puts things in a nutshell in a typically Dickensian manner – although there are some people, I’ve heard of them, that say that Dickens was a man of too many words. ”Mr and Mrs Boffin sat after breakfast, in the Bower, a prey to prosperity.”

"

The idea of "prey" is obviously an intentional theme that Dickens is using. Hexam is "the bird of prey brought down" and the Boffins are "a prey to prosperity." There can be no doubt that the Lammles are preying on Georgina (and probably anyone else they can!), and it wouldn't surprise me if Wegg - currently just an opportunist - ends up preying on the Boffins. I feel sure we'll see this theme continue as we read on.

It can also not be a coincidence that the Boffins thought of a secretary as being a piece of furniture (loved that passage!), after all the talk of Twemlow and table leaves. I look forward to keeping an eye out for future personification of furniture! (I'm starting to think of Beauty and the Beast, and wondering if the furniture will do a dance number for us at some point.)

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: " The Chapter already starts in a way that puts things in a nutshell in a typically Dickensian manner – although there are some people, I’ve heard of them, that say that Dickens was..."

I really enjoyed your suggestion of how the word "prey"can be seen as a motif in the novel. I too think we will see more prey as the novel progresses.

If anyone can make furniture dance and be believable it will be Dickens.

I really enjoyed your suggestion of how the word "prey"can be seen as a motif in the novel. I too think we will see more prey as the novel progresses.

If anyone can make furniture dance and be believable it will be Dickens.

I was also struck by the fact that Rokesmith didn't accept, or expect, a salary - at least a minimal one. I understand the idea of employment on a trial basis, but it seems obvious to me that Rokesmith, who, at this point, seems upstanding, has some interest in inserting himself into the Boffins' affairs. What is he after? Information? Embezzlement? Some kind of power that has yet to be fleshed out? In keeping with the "prey" theme, it's hard not to assume that Rokesmith is preying on the Boffins in some way, but we have yet to figure out how. Despite the suspicions I have, I like Rokesmith and, while he's mysterious, he seems like a good person. But as someone said earlier, the ones who seem respectable may well turn out to be the most nefarious.

I was also struck by the fact that Rokesmith didn't accept, or expect, a salary - at least a minimal one. I understand the idea of employment on a trial basis, but it seems obvious to me that Rokesmith, who, at this point, seems upstanding, has some interest in inserting himself into the Boffins' affairs. What is he after? Information? Embezzlement? Some kind of power that has yet to be fleshed out? In keeping with the "prey" theme, it's hard not to assume that Rokesmith is preying on the Boffins in some way, but we have yet to figure out how. Despite the suspicions I have, I like Rokesmith and, while he's mysterious, he seems like a good person. But as someone said earlier, the ones who seem respectable may well turn out to be the most nefarious.

Tristram wrote: Betty Higden also looks after three other kids, one of them a boy called Sloppy because he was found on a sloppy night."

Tristram wrote: Betty Higden also looks after three other kids, one of them a boy called Sloppy because he was found on a sloppy night."It's one of only three I haven't read yet, but I think of Sloppy as being a similar character to Barnaby Rudge. Am I on target or off base on that comparison?

The episode when the Boffins went to visit the home of the potential orphan had me tied up in knots. There was a lump in my throat and there were hand grenades in my tummy. I was waiting for little Johnny to be whisked off in floods of tears and with his grandmother to be rocking herself back and forward in her distraction .

The episode when the Boffins went to visit the home of the potential orphan had me tied up in knots. There was a lump in my throat and there were hand grenades in my tummy. I was waiting for little Johnny to be whisked off in floods of tears and with his grandmother to be rocking herself back and forward in her distraction . I love Mrs Boffin even more now. She had the sensitivity to pull out and not push the issue. That was such an emotional scene.

LindaH wrote: "Having also read these chapters last night, I am appreciative of your facility for summary, Tristram.

As to your question, John, wouldn't it be the title character?"

Thank you very much, Linda!

As to the main character, I'm really at a loss. If it were the title character, it should be the secretary, John Rokesmith, but he is, to me, one of the least interesting characters. I'm much more interested in the Boffins, in whether Riderhood will have his comeuppance, and in what the Lammles are going to do to Georgiana, hoping, of course, they will fail.

We already had a novel with an eponymous character who hardly played any role at all - remember, it was Barnaby Rudge.

As to your question, John, wouldn't it be the title character?"

Thank you very much, Linda!

As to the main character, I'm really at a loss. If it were the title character, it should be the secretary, John Rokesmith, but he is, to me, one of the least interesting characters. I'm much more interested in the Boffins, in whether Riderhood will have his comeuppance, and in what the Lammles are going to do to Georgiana, hoping, of course, they will fail.

We already had a novel with an eponymous character who hardly played any role at all - remember, it was Barnaby Rudge.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: Betty Higden also looks after three other kids, one of them a boy called Sloppy because he was found on a sloppy night."

It's one of only three I haven't read yet, but I think of S..."

I thought Barnaby more realistic, all in all, whereas I cannot help thinking of Sloppy as just a whimsical extension of the mangle he is operating, or of a kind of accessory to Betty Higden. There's no real life in him, to me - nor in Betty's two other Minders.

It's one of only three I haven't read yet, but I think of S..."

I thought Barnaby more realistic, all in all, whereas I cannot help thinking of Sloppy as just a whimsical extension of the mangle he is operating, or of a kind of accessory to Betty Higden. There's no real life in him, to me - nor in Betty's two other Minders.

Mary Lou wrote: "I was also struck by the fact that Rokesmith didn't accept, or expect, a salary - at least a minimal one. I understand the idea of employment on a trial basis, but it seems obvious to me that Rokes..."

I wonder that Mr Boffin should not feel some slight distrust seeing how keen Rokesmith is to get the job. And then, how can he possibly afford to work without payment? We also learned that he advanced some rent money to the Wilfers on condition that they do not demand a character certificate from him. What kind of person is he who is so free and easy with his money in certain situations and yet so absolutely not free and easy with regard to giving out information about himself?

Is he another example of a bird of prey, just cleverer than Wegg?

I wonder that Mr Boffin should not feel some slight distrust seeing how keen Rokesmith is to get the job. And then, how can he possibly afford to work without payment? We also learned that he advanced some rent money to the Wilfers on condition that they do not demand a character certificate from him. What kind of person is he who is so free and easy with his money in certain situations and yet so absolutely not free and easy with regard to giving out information about himself?

Is he another example of a bird of prey, just cleverer than Wegg?

Peter wrote: "If anyone can make furniture dance and be believable it will be Dickens."

I just love that sentence, Peter!

I just love that sentence, Peter!

Chapter 14 is yet another remarkable feat of writing. And yes, Linda, the weekly summary given by Tristram and Kim are incredible, aren't they? Quite the trio - Charles, Tristram and Kim.

I'm finding OMF an interesting reading experience. On the one hand, Dickens is in full flight with his style, characters, metaphors, similes and all the other goodies of his style. On the other hand, I am having some difficulty engaging with the story so far. It could be the seemingly disjointed storylines (although I know Dickens will knit them together soon) and it could be the fact that so far the parts are great I can't seem to get the rubric to work. Or, it could be just me, which I suspect is the most accurate assessment.

I'm finding OMF an interesting reading experience. On the one hand, Dickens is in full flight with his style, characters, metaphors, similes and all the other goodies of his style. On the other hand, I am having some difficulty engaging with the story so far. It could be the seemingly disjointed storylines (although I know Dickens will knit them together soon) and it could be the fact that so far the parts are great I can't seem to get the rubric to work. Or, it could be just me, which I suspect is the most accurate assessment.

"Black with wet, and altered to the eye with white patches of hail and sleet, the huddled buildings looked lower than usual, as if they were cowering, and had shrunk with the cold."

What great writing. The personification of the buildings as they huddle together gives us an additional image of what Riderhood and the men must be feeling and responding to in regards to the weather. The weather itself is reflective of the men's cold, unpleasant task. It is as if the weather is conspiring to challenge the actions of the men.

We are told the men are engaged in "an awful sort of fishing." When Gaffer's body is found we are told that in bad weather he would always " hang this coil of line round his neck." Gaffer is found and we read that "his own boat tows him dead." And then we are told that there was "silver" in his pocket. What to make of all this?

Dickens's use of the foul weather has set the stage with pathetic fallacy. To what extent are we to believe that Gaffer died through the negligence of his own doing? Dickens explicitly says that is was "silver" in Gaffer's pockets, not coins, or change or money. Are we meant to read the specific mention of silver as an allusion to betrayal? If so, who betrayed him?

Was Gaffer's death an accident, a murder, a revenge killing? Whatever the answer one thing is certain. Lizzie has just set her brother free by giving him money. This act was to protect him and his future. Now, Gaffer is dead. Effectively, Dickens has made Lizzie an orphan in a few chapters. I feel very uncomfortable with Eugene's overt interest in her.

Consider the prey that Dickens has created. Mary Lou has pointed out this theme. Will Lizzie become easy prey now that she is alone?

What great writing. The personification of the buildings as they huddle together gives us an additional image of what Riderhood and the men must be feeling and responding to in regards to the weather. The weather itself is reflective of the men's cold, unpleasant task. It is as if the weather is conspiring to challenge the actions of the men.

We are told the men are engaged in "an awful sort of fishing." When Gaffer's body is found we are told that in bad weather he would always " hang this coil of line round his neck." Gaffer is found and we read that "his own boat tows him dead." And then we are told that there was "silver" in his pocket. What to make of all this?

Dickens's use of the foul weather has set the stage with pathetic fallacy. To what extent are we to believe that Gaffer died through the negligence of his own doing? Dickens explicitly says that is was "silver" in Gaffer's pockets, not coins, or change or money. Are we meant to read the specific mention of silver as an allusion to betrayal? If so, who betrayed him?

Was Gaffer's death an accident, a murder, a revenge killing? Whatever the answer one thing is certain. Lizzie has just set her brother free by giving him money. This act was to protect him and his future. Now, Gaffer is dead. Effectively, Dickens has made Lizzie an orphan in a few chapters. I feel very uncomfortable with Eugene's overt interest in her.

Consider the prey that Dickens has created. Mary Lou has pointed out this theme. Will Lizzie become easy prey now that she is alone?

The "disjointed storylines" are a.major aspect of this novel, and so I have to believe as Peter, Dickens will connect them all. When I draw lines between characters already connected, and ask, who has the most connections so far, I come up with the two Boffins and the two barristers, Wrayburn and Lightwood. When I ask, who is connected to both the Boffins and the barristers, I get Rokesmith. His connection with Lightwood is implied. He is also connected to the Wilbers. I'd put my money on Rokesmith.

The "disjointed storylines" are a.major aspect of this novel, and so I have to believe as Peter, Dickens will connect them all. When I draw lines between characters already connected, and ask, who has the most connections so far, I come up with the two Boffins and the two barristers, Wrayburn and Lightwood. When I ask, who is connected to both the Boffins and the barristers, I get Rokesmith. His connection with Lightwood is implied. He is also connected to the Wilbers. I'd put my money on Rokesmith.The other reason he feels like the main character-in--waiting to me, is that he is the least funny. Everyone else has laughable foibles or nefarious intentions. I keep wondering, what will Dickens do with him?

LindaH wrote: "The "disjointed storylines" are a.major aspect of this novel, and so I have to believe as Peter, Dickens will connect them all. When I draw lines between characters already connected, and ask, who ..."

Ah, elementary. Good logic Linda.

We get another look at Rokesmith in Chapter 15. This chapter has a definite tinge of the Gothic. We have a home with many unlived in and seemingly unexplored rooms, a home whose rooms are kept "exactly as [the house] came to them... Even now, nothing is changed but [Boffin's] own room below-stairs." Thus, while time has past, time is also preserved in the house. Within this home Mrs Boffin feels a presence and imagines she sees and feels "the faces of the old man and the two children" in the house. She felt "a face growing out of the dark." If this face is "growing out of the dark" (my italics) then it must be coming into the light of recognition and acknowledgement.

Well. An old house. Images and faces. A mystery unsolved and unexplained. What can trigger such a memory? In the Gothic it would be the presence of the past trying to claim itself in the present. Gothic homes hold their history and often release it to those who must either wage war with the past or come to embrace the past. The Boffin's are simply too nice to be cast as evil in any way. Thus, theories of how the past evolves into the presence must be considered. How can the Boffins bring an object, or,in this case, a person, into the present to quiet their own soul and offer the spirit(s) of the past recognition?

I think it would be wise to keep our knowledge of the Gothic tradition close by whenever we spend time in the Boffin house or those who dwell there.

Ah, elementary. Good logic Linda.

We get another look at Rokesmith in Chapter 15. This chapter has a definite tinge of the Gothic. We have a home with many unlived in and seemingly unexplored rooms, a home whose rooms are kept "exactly as [the house] came to them... Even now, nothing is changed but [Boffin's] own room below-stairs." Thus, while time has past, time is also preserved in the house. Within this home Mrs Boffin feels a presence and imagines she sees and feels "the faces of the old man and the two children" in the house. She felt "a face growing out of the dark." If this face is "growing out of the dark" (my italics) then it must be coming into the light of recognition and acknowledgement.

Well. An old house. Images and faces. A mystery unsolved and unexplained. What can trigger such a memory? In the Gothic it would be the presence of the past trying to claim itself in the present. Gothic homes hold their history and often release it to those who must either wage war with the past or come to embrace the past. The Boffin's are simply too nice to be cast as evil in any way. Thus, theories of how the past evolves into the presence must be considered. How can the Boffins bring an object, or,in this case, a person, into the present to quiet their own soul and offer the spirit(s) of the past recognition?

I think it would be wise to keep our knowledge of the Gothic tradition close by whenever we spend time in the Boffin house or those who dwell there.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 16 is all about “Minders and Re-Minders”, and we see the new secretary starting his job of settling Mr Boffin’s affairs, a task in the execution of which he shows great assiduity and skill ..."

It seems that Rokesmith has some emotional interest in Bella.

"As if she knew." Well, to mix our stories, but we are all detectives as to the mystery of OMF, I think something is afoot with Rokesmith. Dickens is making him too notable to be an insignificant character.

It seems that Rokesmith has some emotional interest in Bella.

"As if she knew." Well, to mix our stories, but we are all detectives as to the mystery of OMF, I think something is afoot with Rokesmith. Dickens is making him too notable to be an insignificant character.

Tristram wrote: "LindaH wrote: "Having also read these chapters last night, I am appreciative of your facility for summary, Tristram.

Tristram wrote: "LindaH wrote: "Having also read these chapters last night, I am appreciative of your facility for summary, Tristram.As to your question, John, wouldn't it be the title character?"

Thank you very..."

Tristram, if I were to look as far as I read, I would also agree about Rokesmith. But it just doesn't seem so, and even the last name does not have that Dickensian quality of it to me.

I guess either my impulse or inclination or wish was for Lizzie.

I probably shouldn't even be posting yet, as I'm still trying to catch you (the group) up. Frankly, I can't believe how much and how well all of you write, you're simply amazing! I find myself lost here, reading post after post, instead of paying attention to Our Mutual Friend!

I probably shouldn't even be posting yet, as I'm still trying to catch you (the group) up. Frankly, I can't believe how much and how well all of you write, you're simply amazing! I find myself lost here, reading post after post, instead of paying attention to Our Mutual Friend!I did want to poke my nose in, however, to say that for me, the title character is not only a 'who', but a 'what' - and the 'what' is money. It's been a long while since I've read OMF, but I have always remembered it as one of his more brutal books insofar as social commentary is concerned.

And now I shall shut up, and happily resume reading in odd moments as work allows.

Jane wrote: "I probably shouldn't even be posting yet, as I'm still trying to catch you (the group) up. Frankly, I can't believe how much and how well all of you write, you're simply amazing! I find myself lost..."

Jane wrote: "I probably shouldn't even be posting yet, as I'm still trying to catch you (the group) up. Frankly, I can't believe how much and how well all of you write, you're simply amazing! I find myself lost..."Jump in any time, Jane! We're happy to have you join the discussion. Dickens has so many non-living characters - money, the river, the furniture... I guess we'll have to wait until the end to determine if money is "our mutual friend" or not.

Mary Lou wrote: "Jump in any time, Jane!"

Mary Lou wrote: "Jump in any time, Jane!"Thank you, Mary Lou! And you're absolutely right about the river; I had forgotten that detail, but all the way back in Chapter 1, Lizzie's father referred to the river as her "best friend".

I am going to learn so much from this group; thank you all for the warm welcome.

Jane wrote: "I probably shouldn't even be posting yet, as I'm still trying to catch you (the group) up. Frankly, I can't believe how much and how well all of you write, you're simply amazing! I find myself lost..."

Hi Jane

Poke your nose in, get your feet wet any time you want. It's all good. Curiosity is our friend and we are glad you are with us.

Hi Jane

Poke your nose in, get your feet wet any time you want. It's all good. Curiosity is our friend and we are glad you are with us.

Tristram wrote: "We also get to know the amount of begging letters that have to be dealt with by Mr Rokesmith, all sorts of people who want to wheedle some money out of the newly-rich Boffin. Our narrator gives a hilarious account of the different strategies these beggars employ..."

Do you know what this reminded me of? The Cheeryble Brothers from Nicholas Nickleby. Do you remember those kind brothers? Dickens said in his preface to the second edition:

"One other quotation from the same Preface may serve to introduce a fact that my readers may think curious.

......“To turn to a more pleasant subject, it may be right to say, that there are two characters in this book which are drawn from life. It is remarkable that what we call the world, which is so very credulous in what professes to be true, is most incredulous in what professes to be imaginary; and that, while, every day in real life, it will allow in one man no blemishes, and in another no virtues, it will seldom admit a very strongly-marked character, either good or bad, in a fictitious narrative, to be within the limits of probability. But those who take an interest in this tale, will be glad to learn that the Brothers Cheeryble live; that their liberal charity, their singleness of heart, their noble nature, and their unbounded benevolence, are no creations of the Author’s brain; but are prompting every day (and oftenest by stealth) some munificent and generous deed in that town of which they are the pride and honour.”......

If I were to attempt to sum up the thousands of letters, from all sorts of people in all sorts of latitudes and climates, which this unlucky paragraph brought down upon me, I should get into an arithmetical difficulty from which I could not easily extricate myself. Suffice it to say, that I believe the applications for loans, gifts, and offices of profit that I have been requested to forward to the originals of the Brothers Cheeryble (with whom I never interchanged any communication in my life) would have exhausted the combined patronage of all the Lord Chancellors since the accession of the House of Brunswick, and would have broken the Rest of the Bank of England."

The Brothers are now dead."

Do you know what this reminded me of? The Cheeryble Brothers from Nicholas Nickleby. Do you remember those kind brothers? Dickens said in his preface to the second edition:

"One other quotation from the same Preface may serve to introduce a fact that my readers may think curious.

......“To turn to a more pleasant subject, it may be right to say, that there are two characters in this book which are drawn from life. It is remarkable that what we call the world, which is so very credulous in what professes to be true, is most incredulous in what professes to be imaginary; and that, while, every day in real life, it will allow in one man no blemishes, and in another no virtues, it will seldom admit a very strongly-marked character, either good or bad, in a fictitious narrative, to be within the limits of probability. But those who take an interest in this tale, will be glad to learn that the Brothers Cheeryble live; that their liberal charity, their singleness of heart, their noble nature, and their unbounded benevolence, are no creations of the Author’s brain; but are prompting every day (and oftenest by stealth) some munificent and generous deed in that town of which they are the pride and honour.”......

If I were to attempt to sum up the thousands of letters, from all sorts of people in all sorts of latitudes and climates, which this unlucky paragraph brought down upon me, I should get into an arithmetical difficulty from which I could not easily extricate myself. Suffice it to say, that I believe the applications for loans, gifts, and offices of profit that I have been requested to forward to the originals of the Brothers Cheeryble (with whom I never interchanged any communication in my life) would have exhausted the combined patronage of all the Lord Chancellors since the accession of the House of Brunswick, and would have broken the Rest of the Bank of England."

The Brothers are now dead."

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "We also get to know the amount of begging letters that have to be dealt with by Mr Rokesmith, all sorts of people who want to wheedle some money out of the newly-rich Boffin. Our n..."

Kim. Thanks for the reminder. I wonder what Dickens would say about the practice of many companies/charities selling their mailing lists to others. I am constantly amazed how many letters of solicitation try and find their way into my pocket. Thank heavens for recycling bins.

Kim. Thanks for the reminder. I wonder what Dickens would say about the practice of many companies/charities selling their mailing lists to others. I am constantly amazed how many letters of solicitation try and find their way into my pocket. Thank heavens for recycling bins.

The Bird of Prey brought down

Chapter 14

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

"In the September 1864 monthly number, Marcus Stone realizes the moment at which Lightwood, Wrayburn, the Inspector, and Riderhood solve the mystery of Gaffer Hexam's empty boat, which Dickens has posed for the reader at the conclusion of Chapter 13, the closing "curtain" of the fourth monthly instalment. Whereas in "The Bird of Prey Brought Down," the backdrop of which is unrelenting rain and a chill wind, Dickens paints vivid word-pictures of the Thames and its shores, in the illustration of the same name Stone creates an impression of driving rain: the backdrop is thoroughly obscured, and only the muddy foreground, the corpse, and the four searchers stand out distinctly. From the text, the figure bending over the corpse would be the Inspector, who has just pulled the body from the water; to the left, readily identified by his fur cap, is waterman Rogue Riderhood; to the right, standing, are the respectably attired attorneys Lightwood and Wrayburn. According to the text, the scene occurs at some water stairs, where the Inspector has pulled in the rope only to discover the lifeless body of the Thames scavenger — "The Bird of Prey" — Gaffer Hexam:

Soon, the form of the bird of prey, dead some hours, lay stretched upon the shore, with a new blast storming at it and clotting the wet hair with hailstones. . . . .

'Now see,' said Mr. Inspector, after mature deliberation: kneeling on one knee beside the body, when they had stood looking down on the drowned man, as he had many a time looked down on many another man: 'the way of it was this. Of course you gentlemen hardly failed to observe that he was towing by the neck and arms.'

In fact, Stone has represented neither Gaffer Hexam's distinctive tow-rope nor the stairs; the two boats, Gaffer Hexam's and Rogue Riderhood's, are but indistinctly shown. The piling (left) is entirely Stone's invention. Disparaging the earlier style of Victorian illustration and praising the realist style of the New Men of the Sixties, J. A. Hammerton in the early twentieth century vastly approved of Marcus Stone's impressionistic illustrations such as this, feeling that they represented an enormous advance in their artistic quality and the disappearance of the old hearty humour of Phiz and Cruikshank. Mr. Stone's illustrations might have been drawn yesterday, for a story by Mr.H. G. Wells or Mrs. Humphry Ward, they are so essentially modern in conception and execution. The niggling, feeble lines of the earlier artists had given place to fine vigorous drawing, instinct with actuality and life-likeness, and as works of art Mr. Marcus Stone's illustrations are on an altogether higher plane than even the best efforts of Phiz."

"They had opened the door at the bottom of the staircase giving on the yard, and they stood in the sun-light, looking at the scrawl of two unsteady childish hands two or three steps up the staircase."

Chapter 15

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"The room was kept like this, Rokesmith," said Mr. Boffin, "against the son's return. In short, everything in the house was kept exactly as it came to us, for him to see and approve. Even now, nothing is changed but our own room below-stairs that you have just left. When the son came home for the last time in his life, and for the last time in his life saw his father, it was most likely in this room that they met."

As the Secretary looked all round it, his eyes rested on a side door in a corner.

"Another staircase," said Mr. Boffin, unlocking the door, "leading down into the yard. We'll go down this way, as you may like to see the yard, and it's all in the road. When the son was a little child, it was up and down these stairs that he mostly came and went to his father. He was very timid of his father. I've seen him sit on these stairs, in his shy way, poor child, many a time. Mr. and Mrs. Boffin have comforted him, sitting with his little book on these stairs, often."

"Ah! And his poor sister too," said Mrs Boffin. "And here's the sunny place on the white wall where they one day measured one another. Their own little hands wrote up their names here, only with a pencil; but the names are here still, and the poor dears gone for ever."

"We must take care of the names, old lady," said Mr. Boffin. "We must take care of the names. They shan't be rubbed out in our time, nor yet, if we can help it, in the time after us. Poor little children!"

"Ah, poor little children!" said Mrs. Boffin.

They had opened the door at the bottom of the staircase giving on the yard, and they stood in the sunlight, looking at the scrawl of the two unsteady childish hands two or three steps up the staircase. There was something in this simple memento of a blighted childhood, and in the tenderness of Mrs. Boffin, that touched the Secretary.

Mr. Boffin then showed his new man of business the Mounds, and his own particular Mound which had been left him as his legacy under the will before he acquired the whole estate."

Commentary:

"The woodcut for Book One, Chapter Fifteen, "Two New Servants," depicts the Boffins showing their new secretary, John Rokesmith about the old house, pointing out where John Harmon and his sister experimented with writing on the plaster in a stairwell. Rokesmith soon puts their affairs in order and advances their search for an adoptable child. The Boffins, having inherited the estate of their old master after the untimely death of the legitimate heir, John Harmon, are eager to explore the world, experience literature, and perform philanthropic acts. Here, Noddy (Nicodemus) and his equally good-hearted wife, Henrietta ("a stout lady of rubicund and cheerful aspect"), reveal their adoption scheme.

The "two servants" mentioned in the chapter title are Silas Wegg, Boffin's reader and interpreter of classical literature, and now caretaker of the Harmon property, and John Rokesmith, who has just become the Boffins' personal secretary — a necessity now that the semi-literate Boffins are wealthy. Although they insist that they do not intend to sell the old Harmon mansion which they have unexpectedly inherited, the Boffins are not entirely at their ease in their master's home, which Mrs. Boffin feels is haunted by the ghosts of the children. They are thinking about selling the garbage "mounds," and plan to live elsewhere. Having agreed upon Rokesmith's offer to serve as their manager, Mr. Boffin gives the young man a tour of the house, and describes how the Harmon children brought the old place to life with their playing and laughter. As Boffin shows Rokesmith about the buildings and grounds, he ruminates on how the deceased master's furnishings still reflect his grasping, miserly personality. After viewing the room to be kept up "against the son's return", they take the staircase down to the yard. "And here's the sunny place on the white wall where they one day measured one another. Their own little hands wrote up their names here with only a pencil; but the names are here still, and the poor dears gone forever". This, then, is the whitewashed plaster wall which Mrs. Boffin is examining in the illustration as her husband narrates this bit of history. The illustrator has turned the secretary's face away from the reader, who must supply for himself or herself the expression on the young man's face. Beyond the stout door on the right is a wagon in the yard: "There was something in this simple memento of a blighted childhood, and in the tenderness of Mrs. Boffin, that touched the Secretary." The Boffins here are much as they appeared in Marcus Stone's July 1864 serial illustration The Boffin Progress, and the professional young man who now attends them in the Mahoney illustration is clearly based on the John Rokesmith in Stone's Mrs. Boffin discovers an Orphan (realising a scene later in serial Part Five)."

Mrs. Boffin discovers an Orphan

Chapter 16

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

"For the September 1864 installment, Marcus Stone's second illustration realizes the moment at which the new "Secretary," John Rokesmith, and his employer, the velvet-clad Mrs. Boffin, having left the carriage in the village square, approach Betty Higden's humble cottage and encounter her toddler grandson, Johnny, playing in the doorway in chapter 16, "Minders and Reminders." Like many modern parents and grandparents, Betty has found it necessary to erect a makeshift child-gate in the doorway to prevent the child's escaping. Shortly the visitors will discover that Betty is a "child-minder," and that she has charge of a pair of neighbor children whom she has dubbed "Toddles and Poddles." The passage realized is this:

"After many inquiries and defeats, there was pointed out to them in a lane, a very small cottage residence, with a board across the open doorway, hooked on to which board by the armpits was a young gentleman of tender years, angling for mud with a headless wooden horse and line. In this young sportsman, distinguished by a crisply curling auburn head and a bluff countenance, the Secretary descried the orphan."

In a letter of June 14 1864 to the illustrator, Dickens proposed precisely this scene for the fifth installment, describing it as "The Orphan Fishing", having also proposed the scene in which Gaffer Hexam's body is brought to shore as the subject of the other illustration for the fifth monthly number. As a letter dated July 7 1864 makes clear, Dickens entitled both illustrations himself. Whereas Stone, interested in setting up in the viewer's mind a sense of anticipation about what Mrs. Boffin and her secretary will discover within Betty Higden's ivy-covered Brentford cottage, has convincingly drawn the three figures and supplied a number of external details that the text lacks with respect to the condition of the poor widow's cottage, two other nineteenth-century illustrators — Sol Eytinge in "Betty Higden, Sloppy, and the Innocents" and the Household Edition's James Mahoney in the 1870s — chose to focus instead on the cottage interior and the occupants, realizing in particular the figure and character of the working-class widow Betty Higden. While there is a woodenness about Mahoney's seven figures and their disposition in the interior scene, "Come Here, Toddles and Poddles," for which salient interior details and the presence of Sloppy do not compensate and in no way give a sense of Betty's "minding-school," Eytinge conveys a strong sense of the characters of the proud, hard-working widow and her "Natural" assistant. Since Dickens disparaged Stone's interior scenes for "a rather objectionable sameness", one may assume that he enjoyed Stone's skillful use of the exterior of the cottage here, relishing such details as the sagging thatch, worn lintels, spade and broom (right, foreground). Although nobody appears to be "minding" the toddler, Stone has included a darkened figure against the diamond window-panes of the interior, foiling the pudgy-armed infant whose "fishing" here recalls the grimmer business of Gaffer Hexam and Rogue Riderhood, so that the picture seems to possess an intense, "inner" life. Stone provides a detailed realization of the interior of Betty's cottage amounting to a character study in "Our Johnny," in the ninth chapter of Book Two."

"Come here, Toddles and Poddles"

Chapter 16

James Mahoney

1875

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"The visitors glanced at the long boy, who seemed to indicate by a broader stare of his mouth and eyes that in him Sloppy stood confessed.

For I ain't, you must know," said Betty, "much of a hand at reading writing-hand, though I can read my Bible and most print. And I do love a newspaper. You mightn't think it, but Sloppy is a beautiful reader of a newspaper. He do the Police in different voices."

The visitors again considered it a point of politeness to look at Sloppy, who, looking at them, suddenly threw back his head, extended his mouth to its utmost width, and laughed loud and long. At this the two innocents, with their brains in that apparent danger, laughed, and Mrs. Higden laughed, and the orphan laughed, and then the visitors laughed. Which was more cheerful than intelligible.

Then Sloppy seeming to be seized with an industrious mania or fury, turned to at the mangle, and impelled it at the heads of the innocents with such a creaking and rumbling, that Mrs. Higden stopped him.

"The gentlefolks can't hear themselves speak, Sloppy. Bide a bit, bide a bit!"

"Is that the dear child in your lap?" said Mrs. Boffin.

"Yes, ma'am, this is Johnny."

"Johnny, too!" cried Mrs. Boffin, turning to the Secretary; "already Johnny! Only one of the two names left to give him! He's a pretty boy."

With his chin tucked down in his shy childish manner, he was looking furtively at Mrs. Boffin out of his blue eyes, and reaching his fat dimpled hand up to the lips of the old woman, who was kissing it by times.

"Yes, ma'am, he's a pretty boy, he's a dear darling boy, he's the child of my own last left daughter's daughter. But she's gone the way of all the rest."

"Those are not his brother and sister?" said Mrs. Boffin. "Oh, dear no, ma'am. Those are Minders."

"Minders?" the Secretary repeated.

"Left to he Minded, sir. I keep a Minding-School. I can take only three, on account of the Mangle. But I love children, and Four-pence a week is Four-pence. Come here, Toddles and Poddles."

Toddles was the pet-name of the boy; Poddles of the girl. At their little unsteady pace, they came across the floor, hand-in-hand, as if they were traversing an extremely difficult road intersected by brooks, and, when they had had their heads patted by Mrs. Betty Higden, made lunges at the orphan, dramatically representing an attempt to bear him, crowing, into captivity and slavery. All the three children enjoyed this to a delightful extent, and the sympathetic Sloppy again laughed long and loud. When it was discreet to stop the play, Betty Higden said, "Go to your seats Toddles and Poddles," and they returned hand-in-hand across country, seeming to find the brooks rather swollen by late rains."

Commentary:

"The woodcut for Book One, Chapter Sixteen, "Minders and Re-minders," depicts the interior of aged widow Betty Higden's cottage at Brentford. Although Betty is illiterate, she is a good-hearted and even noble peasant woman whom the Reverend Frank Milvey has discovered is the guardian of an orphan infant, Johnny. Mrs. Boffin, accompanied by her secretary, John Rokesmith visits the unromanticized cottage of a proud but poor widow who has outlived all of her children. Caring for her infant grandchild, Johnny, the sole survivor of her line, Betty makes ends meet by knitting and looking after other people's children, in this case the toddlers whom she has nicknamed Toddles and Poddles. Also evident in the Mahoney illustration is the well-motivated but decidedly odd illegitimate adolescent whom she has rescued from the workhouse, Sloppy (left rear), very much as Dickens describes him: "a very long boy, with a very little head, and an open moth of disproportionate capacity".

Sloppy and the other children appear prominently in Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition wood-engraving Mrs. Higden, Sloppy, and the Innocents (1867), in which the American illustrator has added to Marcus Stone's original conception of the cottager's family by realizing the quirky Dickens child-character not seen in Marcus Stone's Mrs. Boffin discovers an Orphan, the September 1864 illustration showing Mrs. Boffin in her characteristic feathered hat and her professionally-attired secretary, John Rokesmith, discovering the toddler Johnny on the doorstep of Betty Higden's cottage, whom the middle-class visitors will shortly rescue from a tumble into the gutter after he has managed to surmount the board in the doorway intended to prevent such an escape.

Perhaps the detail that, more than any other in the illustration, characterizes Betty's spartan existence is the splintered wooden flooring of her cottage, which in the text is specifically of "brick". Mahoney adds a rattle lying discarded on the floor, but shows "a window of diamond panes", although, perhaps to underscore the simplicity of her existence, the illustrator has not included such details as "a flounce hanging below the chimney-piece, and strings nailed from bottom to top outside the window on which scarlet-beans were to grow in the coming season", a detail perhaps intended to recall the children's story "Jack and the Beanstalk." All of these elements occur in Marcus Stone's Our Johnny (Book Two, Chapter 9). Moreover, Mahoney gives us little sense of Betty's "bright dark eye" and fierce resolution to remain free of the work house and live independently. Mahoney's Sloppy observes Betty's reception of the visitors whom Betty calls "gentlefolks" (presumably, the mangle's handle is just outside the left-hand frame). The "Minders" in pinafores are evidently somewhat younger than Johnny, whom the old woman holds close to her as she watches her charges and listens to Mrs. Boffin. What Mahoney misses entirely is the sense of fun that Betty and the children possess, and the infectious laughter of Sloppy as he works the mangle. Although he misses many of the salient details captured by Stone in Our Johnny, Mahoney captures Betty's genuine interest in the children."

Mrs. Higden, Sloppy, and the Innocents

Chapter 16

Sol Eytinge

1875

Household Edition

Commentary:

To illustrate "Minders and Reminders," Eytinge has focused not on the middle-class woman in search of an orphan to adopt, Mrs. Boffin, or her secretary, John Rokesmith, but on the noble, long-suffering Brentford widow, the resolute survivor of hunger and poverty, Betty Higden, the children whom she minds ("Toddles" and "Poddles"), and in particular the Poor-House orphan and "natural," Sloppy:

"It was then perceived to be a small home with a large mangle in it, at the handle of which machine stood a very long boy, with a very little head, and open mouth of disproportionate capacity that seemed to assist his eyes in staring at the visitors."

Dickens reflects the simple but noble character of Betty Higden in the neatness and cleanliness of the cottage's main room, whose detailed description Eytinge realizes:

"It had a brick floor, and a window of diamond panes, and a flounce hanging below the chimney-piece, and strings nailed from bottom to top outside the window on which scarlet-beans were to grow in the coming season". . . .

However well he realizes the odd but benign Sloppy, Eytinge fails to convey the stoic dignity of Betty Higden and her love for the grandchild on her lap. Nevertheless, Eytinge's treatment of Betty's unconventional family and working class dignity is a considerable advancement over Marcus Stone's in the original Chapman and Hall serial publication. Eytinge permits the reader to enter the honest woman's cottage and see the oddly assorted grouping of children with a focus on the whimsical sloppy, whereas Stone in "Mrs. Boffin Discovers an Orphan" leaves us at the open door of the cottage, wondering who the darkened figure in the door may be in an illustration that captures a precise moment in the text:

"After many inquiries and defeats, there was pointed out to them in a lane, a very small cottage residence, with a board across the open doorway, hooked on to which board by the armpits was a young gentleman of tender years, angling for mud with a headless wooden horse and line."

Whereas Stone, interested in the anticipation of what Mrs. Boffin and her secretary will discover within, has supplied a great many external details that the text lacks with respect to the poor widow's cottage, Eytinge — avoiding depicting any one narrative moment — focuses instead on the interior and the occupants, realizing in particular the buttons on the jacket of the singular and angular mangle-turner, Sloppy:

"Of ungainly make was Sloppy. Too much of him longwise, too little of him broadwise, and too many sharp angles of him angle-wise. One of those shambling male human creatures, born to be indiscreetly candid in the revelation of buttons; every button he had about him glaring at the public to a quite preternatural extent. A considerable capital of knee and elbow and wrist and ankle, had Sloppy, and he didn't know how to dispose of it to the best advantage, but was always investing it in wrong securities, and so getting himself into embarrassed circumstances."

Tristram wrote: "Although our narrator seems to be prejudiced against Wegg, I must say that I rather like his presence in our chapter because he enlivens it with his ramshackle poetry and his cunning ways of doing business.."

The Wegg haters will get plenty of support for their view in this chapter, but he's a poor man who does what he can to survive, and whether or not one likes his character, I think one has to admire his ability as a Dale Carnegie figure.

The Wegg haters will get plenty of support for their view in this chapter, but he's a poor man who does what he can to survive, and whether or not one likes his character, I think one has to admire his ability as a Dale Carnegie figure.

Mary Lou wrote: "I look forward to keeping an eye out for future personification of furniture!."

Birds for Peter, furniture for you!

Birds for Peter, furniture for you!

Is there something mysterious about why Eugene suddenly disappeared from the landing where Gaffer's body was brought to shore? Why was he so quick to absent himself without telling anybody that he was leaving?

I've been thinking this for some time, but the "secretary" passage reminded me again how weird the English are about their language.

Take a secretary of the furniture type. If you're move it into a storage room in your house, it's now lumber. If you throw it out, it's now dust.

Weird!

Take a secretary of the furniture type. If you're move it into a storage room in your house, it's now lumber. If you throw it out, it's now dust.

Weird!

LindaH wrote: "The other reason he feels like the main character-in--waiting to me, is that he is the least funny."

This is indeed a good piece of evidence, Linda! If he is not funny, he in some way must be the male hero for readers to identify with, and probably Bella will be his female counterpart.

This is indeed a good piece of evidence, Linda! If he is not funny, he in some way must be the male hero for readers to identify with, and probably Bella will be his female counterpart.

Peter wrote: ""Black with wet, and altered to the eye with white patches of hail and sleet, the huddled buildings looked lower than usual, as if they were cowering, and had shrunk with the cold."

What great wri..."

I agree completely, Peter, Dickens's writing is once again marvellous and worthwhile reading for the sake of its beauty and imaginativeness. One GR reviewer, Bill Kerwin, whose reviews I always read with great pleasure, once wrote that Dickens was writing prose poems, and I don't think there's a way more apt to describe Dickens's art.

What great wri..."

I agree completely, Peter, Dickens's writing is once again marvellous and worthwhile reading for the sake of its beauty and imaginativeness. One GR reviewer, Bill Kerwin, whose reviews I always read with great pleasure, once wrote that Dickens was writing prose poems, and I don't think there's a way more apt to describe Dickens's art.

Peter wrote: "LindaH wrote: "The "disjointed storylines" are a.major aspect of this novel, and so I have to believe as Peter, Dickens will connect them all. When I draw lines between characters already connected..."

Your thoughts about the meaning of an empty house remind me of what I was thinking when I read Chapter 15: The house shows, in a way, the uselessness and shallowness of mere wealth that, through avarice and human coldness, is not adopted to a purpose but simply seen as a value in itself. Thus, the house is empty instead of bearing testimony of happy lives, and a similar thing can be said of the more luxurious houses of the Veneerings and the Podsnaps: There may be people in them, but in a way they look empty and stale.

Your thoughts about the meaning of an empty house remind me of what I was thinking when I read Chapter 15: The house shows, in a way, the uselessness and shallowness of mere wealth that, through avarice and human coldness, is not adopted to a purpose but simply seen as a value in itself. Thus, the house is empty instead of bearing testimony of happy lives, and a similar thing can be said of the more luxurious houses of the Veneerings and the Podsnaps: There may be people in them, but in a way they look empty and stale.

John wrote: "Tristram wrote: "LindaH wrote: "Having also read these chapters last night, I am appreciative of your facility for summary, Tristram.

As to your question, John, wouldn't it be the title character?..."

To me, Silas Wegg is the principal character: He is always good for a laugh and an expression of disbelief at his chutzpah.

As to your question, John, wouldn't it be the title character?..."

To me, Silas Wegg is the principal character: He is always good for a laugh and an expression of disbelief at his chutzpah.

Jane wrote: "I probably shouldn't even be posting yet, as I'm still trying to catch you (the group) up. Frankly, I can't believe how much and how well all of you write, you're simply amazing! I find myself lost..."

A keen observation, Jane, since money is "our mutual friend" ;-)

A keen observation, Jane, since money is "our mutual friend" ;-)

Everyman wrote: "I've been thinking this for some time, but the "secretary" passage reminded me again how weird the English are about their language.

Take a secretary of the furniture type. If you're move it into ..."

A very insightful comment, Everyman. It makes me think of another strange thing that has often occurred to me: We usually admire people for their beautiful hair and we would think nothing of stroking a person's head. And yet, as soon as hair falls out and one hair finds its way onto a plate, the same thing we admired is suddenly a source of infinite disgust.

Take a secretary of the furniture type. If you're move it into ..."

A very insightful comment, Everyman. It makes me think of another strange thing that has often occurred to me: We usually admire people for their beautiful hair and we would think nothing of stroking a person's head. And yet, as soon as hair falls out and one hair finds its way onto a plate, the same thing we admired is suddenly a source of infinite disgust.

Just for the sake of argument ... if we take the major character to be one whom the other characters revolve around, and who is the centre of much of the corresponding action, then I would nominate the Thames.

To date, the action, the majority of characters and the central image all radiate around the river.

I'm reading Thames: The Biography and learning a great deal about that great river.

To date, the action, the majority of characters and the central image all radiate around the river.

I'm reading Thames: The Biography and learning a great deal about that great river.

Once again, the Marcus Stone illustrations are my favourites. He is able to create not only characters that accurately reflect the letterpress and my imagination, but also establish an effective mood within the illustrations.

Consider, for example, the illustration for Chapter 16. There is a richness of detail both within the focussed characters and the surrounding picture. If you look through the open door over the child's shoulder you see a diamond-shaped lead glass window. There is also the shadowy representation of a person's head and neck and shoulders outlined.

On the bottom right of the illustration we see a shovel leaning on the door frame, a broom on the ground and a small potted plant.

Each of Stone characters in the illustration have emotions portrayed on their faces that are understandable and identifiable rather than comedic or bland. Sol Eytinge's Chapter 16 presents a gummy-like boy on the right side of the illustration. Very strange.

There is a definite eye to detail that enhances the central concept of the Marcus Stone illustration. The Mahoney illustration for Chapter 17, to offer a contrast for discussion, takes us inside the house. The detail is present, such as the lead-glassed window, but nothing is as specific. The characters' faces are expressive, but they lack subtlety , and the physical position of the characters is wooden rather than natural.

Dickens was pleased with the overall work of Marcus Stone illustrations. Somehow, I doubt whether the other illustrators would have pleased him as much.

Consider, for example, the illustration for Chapter 16. There is a richness of detail both within the focussed characters and the surrounding picture. If you look through the open door over the child's shoulder you see a diamond-shaped lead glass window. There is also the shadowy representation of a person's head and neck and shoulders outlined.

On the bottom right of the illustration we see a shovel leaning on the door frame, a broom on the ground and a small potted plant.

Each of Stone characters in the illustration have emotions portrayed on their faces that are understandable and identifiable rather than comedic or bland. Sol Eytinge's Chapter 16 presents a gummy-like boy on the right side of the illustration. Very strange.

There is a definite eye to detail that enhances the central concept of the Marcus Stone illustration. The Mahoney illustration for Chapter 17, to offer a contrast for discussion, takes us inside the house. The detail is present, such as the lead-glassed window, but nothing is as specific. The characters' faces are expressive, but they lack subtlety , and the physical position of the characters is wooden rather than natural.

Dickens was pleased with the overall work of Marcus Stone illustrations. Somehow, I doubt whether the other illustrators would have pleased him as much.

Tristram wrote: "I agree completely, Peter, Dickens's writing is once again marvellous and worthwhile reading for the sake of its beauty and imaginativeness.."