The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 3, Chp. 05 - 07

Our next chapter is titled "The Golden Dustman Falls Into Worse Company" and I'm wondering how much farther he can fall, then I realize that Silas Wegg is back and I know how much more he can fall. We have Mr. Boffin still going to the Bower in the evenings to have Silas Wegg read to him. When they finish the Roman Empire, we're told they move on to Rollins Ancient History and The War of the Jews, but both "break down" long before they are finished. I'm thinking by now it is too bad they can't read a Dickens book. I liked the description of these books they have been reading through;

One evening, when Silas Wegg had grown accustomed to the arrival of his patron in a cab, accompanied by some profane historian charged with unutterable names of incomprehensible peoples, of impossible descent, waging wars any number of years and syllables long, and carrying illimitable hosts and riches about, with the greatest ease, beyond the confines of geography—one evening the usual time passed by, and no patron appeared.

This evening, with Mr. Boffin not having come at the usual time Wegg does receive a visitor, it is Mr. Venus. It seems he is there to tell Silas he is tired of their business of digging through the mounds looking for treasure of one type or another. But Mr. Venus has had enough of it;

‘It’s not so much saying it that I object to,’ returned Mr Venus, ‘as doing it. And having got to do it whether or no, I can’t afford to waste my time on groping for nothing in cinders.’

‘But think how little time you have given to the move, sir, after all,’ urged Wegg. ‘Add the evenings so occupied together, and what do they come to? And you, sir, harmonizer with myself in opinions, views, and feelings, you with the patience to fit together on wires the whole framework of society—I allude to the human skelinton—you to give in so soon!’

‘I don’t like it,’ returned Mr Venus moodily, as he put his head between his knees and stuck up his dusty hair. ‘And there’s no encouragement to go on.’

‘Not them Mounds without,’ said Mr Wegg, extending his right hand with an air of solemn reasoning, ‘encouragement? Not them Mounds now looking down upon us?’

‘They’re too big,’ grumbled Venus. ‘What’s a scratch here and a scrape there, a poke in this place and a dig in the other, to them. Besides; what have we found?’

‘What have we found?’ cried Wegg, delighted to be able to acquiesce. ‘Ah! There I grant you, comrade. Nothing. But on the contrary, comrade, what may we find? There you’ll grant me. Anything.’

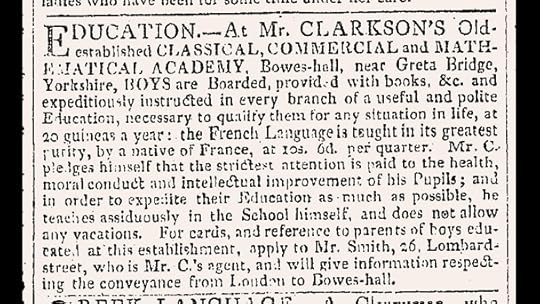

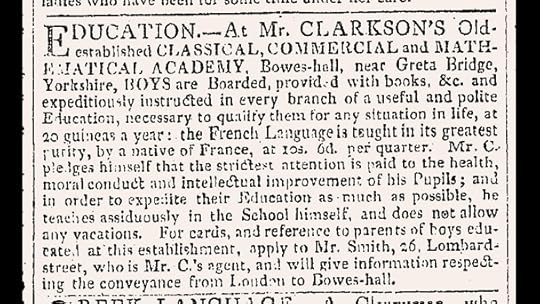

About this time when Silas is attempting to convince Mr. Venus to continue Mr. Boffin does arrive. He arrives with another pile of books that Silas and Venus help carry inside. Once there Mr. Boffin asks Silas to read Lives and Anecdotes of Misers or the Passion of Avarice Displayed in the: Parsimonious Habits Unaccountable Lives and Renaihable Deahts of the Most Notorious Misers of All Ages with a Ferrwords on Frugality and Saving by Frederick Somner Merryweather. Yes, this is a real book, it's even listed on goodreads. Mr. Boffin seems to greatly enjoy these readings, especially the ones that would have the miser hiding his or her money, papers, and wills, things like that. When the reading is complete Mr. Boffin goes to make a survey of the mounds telling them he has sold them, and even though he tells them he wants to go alone, they follow after him. Eventually they see him climb to the top of one of the mounds and dig a bottle out of the ashes. And now as we leave the chapter, Silas wants to know what is in the bottle so much he wants to try to get the bottle by force, but he is stopped by Mr. Venus;

‘He mustn’t go,’ he cried. ‘We mustn’t let him go? He has got that bottle about him. We must have that bottle.’

‘Why, you wouldn’t take it by force?’ said Venus, restraining him.

‘Wouldn’t I? Yes I would. I’d take it by any force, I’d have it at any price! Are you so afraid of one old man as to let him go, you coward?’

‘I am so afraid of you, as not to let you go,’ muttered Venus, sturdily, clasping him in his arms.

‘Did you hear him?’ retorted Wegg. ‘Did you hear him say that he was resolved to disappoint us? Did you hear him say, you cur, that he was going to have the Mounds cleared off, when no doubt the whole place will be rummaged? If you haven’t the spirit of a mouse to defend your rights, I have. Let me go after him.’

As in his wildness he was making a strong struggle for it, Mr Venus deemed it expedient to lift him, throw him, and fall with him; well knowing that, once down, he would not be up again easily with his wooden leg. So they both rolled on the floor, and, as they did so, Mr Boffin shut the gate.

One evening, when Silas Wegg had grown accustomed to the arrival of his patron in a cab, accompanied by some profane historian charged with unutterable names of incomprehensible peoples, of impossible descent, waging wars any number of years and syllables long, and carrying illimitable hosts and riches about, with the greatest ease, beyond the confines of geography—one evening the usual time passed by, and no patron appeared.

This evening, with Mr. Boffin not having come at the usual time Wegg does receive a visitor, it is Mr. Venus. It seems he is there to tell Silas he is tired of their business of digging through the mounds looking for treasure of one type or another. But Mr. Venus has had enough of it;

‘It’s not so much saying it that I object to,’ returned Mr Venus, ‘as doing it. And having got to do it whether or no, I can’t afford to waste my time on groping for nothing in cinders.’

‘But think how little time you have given to the move, sir, after all,’ urged Wegg. ‘Add the evenings so occupied together, and what do they come to? And you, sir, harmonizer with myself in opinions, views, and feelings, you with the patience to fit together on wires the whole framework of society—I allude to the human skelinton—you to give in so soon!’

‘I don’t like it,’ returned Mr Venus moodily, as he put his head between his knees and stuck up his dusty hair. ‘And there’s no encouragement to go on.’

‘Not them Mounds without,’ said Mr Wegg, extending his right hand with an air of solemn reasoning, ‘encouragement? Not them Mounds now looking down upon us?’

‘They’re too big,’ grumbled Venus. ‘What’s a scratch here and a scrape there, a poke in this place and a dig in the other, to them. Besides; what have we found?’

‘What have we found?’ cried Wegg, delighted to be able to acquiesce. ‘Ah! There I grant you, comrade. Nothing. But on the contrary, comrade, what may we find? There you’ll grant me. Anything.’

About this time when Silas is attempting to convince Mr. Venus to continue Mr. Boffin does arrive. He arrives with another pile of books that Silas and Venus help carry inside. Once there Mr. Boffin asks Silas to read Lives and Anecdotes of Misers or the Passion of Avarice Displayed in the: Parsimonious Habits Unaccountable Lives and Renaihable Deahts of the Most Notorious Misers of All Ages with a Ferrwords on Frugality and Saving by Frederick Somner Merryweather. Yes, this is a real book, it's even listed on goodreads. Mr. Boffin seems to greatly enjoy these readings, especially the ones that would have the miser hiding his or her money, papers, and wills, things like that. When the reading is complete Mr. Boffin goes to make a survey of the mounds telling them he has sold them, and even though he tells them he wants to go alone, they follow after him. Eventually they see him climb to the top of one of the mounds and dig a bottle out of the ashes. And now as we leave the chapter, Silas wants to know what is in the bottle so much he wants to try to get the bottle by force, but he is stopped by Mr. Venus;

‘He mustn’t go,’ he cried. ‘We mustn’t let him go? He has got that bottle about him. We must have that bottle.’

‘Why, you wouldn’t take it by force?’ said Venus, restraining him.

‘Wouldn’t I? Yes I would. I’d take it by any force, I’d have it at any price! Are you so afraid of one old man as to let him go, you coward?’

‘I am so afraid of you, as not to let you go,’ muttered Venus, sturdily, clasping him in his arms.

‘Did you hear him?’ retorted Wegg. ‘Did you hear him say that he was resolved to disappoint us? Did you hear him say, you cur, that he was going to have the Mounds cleared off, when no doubt the whole place will be rummaged? If you haven’t the spirit of a mouse to defend your rights, I have. Let me go after him.’

As in his wildness he was making a strong struggle for it, Mr Venus deemed it expedient to lift him, throw him, and fall with him; well knowing that, once down, he would not be up again easily with his wooden leg. So they both rolled on the floor, and, as they did so, Mr Boffin shut the gate.

And finally, we have Chapter 7 titled, "The Friendly Move Takes Up A Strong Position". We are just moving on from the last chapter.

‘Brother,’ said Wegg, at length breaking the silence, ‘you were right, and I was wrong. I forgot myself.’

Mr Venus knowingly cocked his shock of hair, as rather thinking Mr Wegg had remembered himself, in respect of appearing without any disguise.

‘But comrade,’ pursued Wegg, ‘it was never your lot to know Miss Elizabeth, Master George, Aunt Jane, nor Uncle Parker.’

Mr Venus admitted that he had never known those distinguished persons, and added, in effect, that he had never so much as desired the honour of their acquaintance.

‘Don’t say that, comrade!’ retorted Wegg: ‘No, don’t say that! Because, without having known them, you never can fully know what it is to be stimilated to frenzy by the sight of the Usurper.’

I'm wondering if Silas is just a tiny bit crazy. And since Mr. Venus has never met these non-existent people, the conversation moves on to things that really exist. It seems that Silas has found something in one of the mounds but hasn't mentioned it to Mr. Venus. Yes, he has found something, a cash box, and his reason for not mentioning it is because he wanted to give Mr. Venus a sap—pur—ize. Whatever his reason, he has offended Mr. Venus especially when he goes on to say that he had already opened the box and found a will in it.

‘This is great news indeed, Mr Wegg. There’s no denying it. But I could have wished you had told it me before you got your fright to-night, and I could have wished you had ever asked me as your partner what we were to do, before you thought you were dividing a responsibility.’

‘—Hear me out!’ cried Wegg. ‘I knew you was a-going to say so. But alone I bore the anxiety, and alone I’ll bear the blame!’ This with an air of great magnanimity.

‘No,’ said Venus. ‘Let’s see this will and this box.’

‘Do I understand, brother,’ returned Wegg with considerable reluctance, ‘that it is your wish to see this will and this—?’

Mr Venus smote the table with his hand.

‘—Hear me out!’ said Wegg. ‘Hear me out! I’ll go and fetch ‘em.’

He does fetch it but doesn't like opening it there thinking that "he" may return, so they go to the shop of Mr. Venus and there read the will. Silas tells us it has been regularly executed, regularly witnessed, very short. The will tells us that since he has never made friends and has a rebellious family, he gives to Nicodemus Boffin the Little Mound, which is quite enough for him, and gives the whole rest and residue of his property to the Crown.’ They then agree that Mr. Venus will keep the will and Silas will keep the box and label. They are going to use this will as blackmail against Mr. Boffin. Silas says Mr. Boffin would pay any price to get that will. When Silas leaves he tries to think of a way out of his partnership with Mr. Venus thinking that he has been worthless. Instead of going home, he first goes to the home of the Boffins, we'll end with his visit;

Mr Boffin’s shadow passed upon the blinds of three large windows as he trotted down the room, and passed again as he went back.

‘Yoop!’ cried Wegg. ‘You’re there, are you? Where’s the bottle? You would give your bottle for my box, Dustman!’

Having now composed his mind for slumber, he turned homeward. Such was the greed of the fellow, that his mind had shot beyond halves, two-thirds, three-fourths, and gone straight to spoliation of the whole. ‘Though that wouldn’t quite do,’ he considered, growing cooler as he got away. ‘That’s what would happen to him if he didn’t buy us up. We should get nothing by that.’

We so judge others by ourselves, that it had never come into his head before, that he might not buy us up, and might prove honest, and prefer to be poor. It caused him a slight tremor as it passed; but a very slight one, for the idle thought was gone directly.

‘He’s grown too fond of money for that,’ said Wegg; ‘he’s grown too fond of money.’ The burden fell into a strain or tune as he stumped along the pavements. All the way home he stumped it out of the rattling streets, piano with his own foot, and forte with his wooden leg, ‘He’s grown too fond of money for that, he’s grown too fond of money.’

Even next day Silas soothed himself with this melodious strain, when he was called out of bed at daybreak, to set open the yard-gate and admit the train of carts and horses that came to carry off the little Mound. And all day long, as he kept unwinking watch on the slow process which promised to protract itself through many days and weeks, whenever (to save himself from being choked with dust) he patrolled a little cinderous beat he established for the purpose, without taking his eyes from the diggers, he still stumped to the tune: He’s grown too fond of money for that, he’s grown too fond of money.’

‘Brother,’ said Wegg, at length breaking the silence, ‘you were right, and I was wrong. I forgot myself.’

Mr Venus knowingly cocked his shock of hair, as rather thinking Mr Wegg had remembered himself, in respect of appearing without any disguise.

‘But comrade,’ pursued Wegg, ‘it was never your lot to know Miss Elizabeth, Master George, Aunt Jane, nor Uncle Parker.’

Mr Venus admitted that he had never known those distinguished persons, and added, in effect, that he had never so much as desired the honour of their acquaintance.

‘Don’t say that, comrade!’ retorted Wegg: ‘No, don’t say that! Because, without having known them, you never can fully know what it is to be stimilated to frenzy by the sight of the Usurper.’

I'm wondering if Silas is just a tiny bit crazy. And since Mr. Venus has never met these non-existent people, the conversation moves on to things that really exist. It seems that Silas has found something in one of the mounds but hasn't mentioned it to Mr. Venus. Yes, he has found something, a cash box, and his reason for not mentioning it is because he wanted to give Mr. Venus a sap—pur—ize. Whatever his reason, he has offended Mr. Venus especially when he goes on to say that he had already opened the box and found a will in it.

‘This is great news indeed, Mr Wegg. There’s no denying it. But I could have wished you had told it me before you got your fright to-night, and I could have wished you had ever asked me as your partner what we were to do, before you thought you were dividing a responsibility.’

‘—Hear me out!’ cried Wegg. ‘I knew you was a-going to say so. But alone I bore the anxiety, and alone I’ll bear the blame!’ This with an air of great magnanimity.

‘No,’ said Venus. ‘Let’s see this will and this box.’

‘Do I understand, brother,’ returned Wegg with considerable reluctance, ‘that it is your wish to see this will and this—?’

Mr Venus smote the table with his hand.

‘—Hear me out!’ said Wegg. ‘Hear me out! I’ll go and fetch ‘em.’

He does fetch it but doesn't like opening it there thinking that "he" may return, so they go to the shop of Mr. Venus and there read the will. Silas tells us it has been regularly executed, regularly witnessed, very short. The will tells us that since he has never made friends and has a rebellious family, he gives to Nicodemus Boffin the Little Mound, which is quite enough for him, and gives the whole rest and residue of his property to the Crown.’ They then agree that Mr. Venus will keep the will and Silas will keep the box and label. They are going to use this will as blackmail against Mr. Boffin. Silas says Mr. Boffin would pay any price to get that will. When Silas leaves he tries to think of a way out of his partnership with Mr. Venus thinking that he has been worthless. Instead of going home, he first goes to the home of the Boffins, we'll end with his visit;

Mr Boffin’s shadow passed upon the blinds of three large windows as he trotted down the room, and passed again as he went back.

‘Yoop!’ cried Wegg. ‘You’re there, are you? Where’s the bottle? You would give your bottle for my box, Dustman!’

Having now composed his mind for slumber, he turned homeward. Such was the greed of the fellow, that his mind had shot beyond halves, two-thirds, three-fourths, and gone straight to spoliation of the whole. ‘Though that wouldn’t quite do,’ he considered, growing cooler as he got away. ‘That’s what would happen to him if he didn’t buy us up. We should get nothing by that.’

We so judge others by ourselves, that it had never come into his head before, that he might not buy us up, and might prove honest, and prefer to be poor. It caused him a slight tremor as it passed; but a very slight one, for the idle thought was gone directly.

‘He’s grown too fond of money for that,’ said Wegg; ‘he’s grown too fond of money.’ The burden fell into a strain or tune as he stumped along the pavements. All the way home he stumped it out of the rattling streets, piano with his own foot, and forte with his wooden leg, ‘He’s grown too fond of money for that, he’s grown too fond of money.’

Even next day Silas soothed himself with this melodious strain, when he was called out of bed at daybreak, to set open the yard-gate and admit the train of carts and horses that came to carry off the little Mound. And all day long, as he kept unwinking watch on the slow process which promised to protract itself through many days and weeks, whenever (to save himself from being choked with dust) he patrolled a little cinderous beat he established for the purpose, without taking his eyes from the diggers, he still stumped to the tune: He’s grown too fond of money for that, he’s grown too fond of money.’

And back to the misers; as to the misers mentioned,

Daniel Dancer (1716–1794) was a notorious English miser whose life was documented soon after his death and continued in print over the following century. The miser Daniel Dancer was born in Pinner, then a rural area in the county of Middlesex, in 1716. His grandfather and father were both noted in their time as misers, and are only less famous because their accumulation of wealth was less. Daniel was the eldest of four children and inherited the family estate, eighty acres of rich meadow land and an adjoining farm, when his father died in 1736.

Hitherto Dancer had given no manifestation of his miserly instincts, but now, in company with his only sister, who shared his tastes and lived with him as his housekeeper, he commenced a life of the utmost seclusion and most rigid parsimony. His lands were allowed to lie fallow so that the expense of cultivation might be avoided. He took only one meal a day, consisting invariably of a little baked meat and a hard-boiled dumpling, a sufficient quantity of which to last the week was prepared every Saturday night. His clothing consisted mainly of hay bands, which were swathed round his feet for boots and round his body for a coat, but it was his habit to purchase one new shirt every year. And after his sister's death in 1766, he used a fraction of her bequest to buy a second-hand pair of black stockings to put himself in decent mourning.

The miser's only dealing with others arose from the sale of his hay. He was seldom seen, except when he was out gathering logs of wood from the common, or old iron, or sheep's dung under the hedges. To prevent theft, he fastened his door up and got into his house through the upper window, to ascend which he made use of a ladder and drew it up after him. The sole person who could be said to be at all intimately acquainted with the Dancers was a Lady Tempest, the widow of Sir Henry Tempest, a Yorkshire baronet. To this lady Dancer's sister had intended to leave her own private property, but she died before she could sign her will. There then arose a lawsuit among her three brothers as to the distribution of her money, the result of which was that Daniel was awarded two-thirds of the sum on the ground of his having kept her for thirty years.

To fill his sister's place Dancer engaged a servant named Griffiths, whose manner of living was as penurious as his own. The two lived together in Dancer's tumble-down house till the master's death, which took place 30 Sept. 1794. In his last moments he was tended by Lady Tempest, who had shown uniform kindness to the old man, and who was rewarded by being made his sole legatee.

John Elwes (a.k.a. "Elwes the Miser"), MP was a Member of Parliament (MP) in Great Britain for Berkshire (1772–1784) and a noted eccentric and miser, suggested to be an inspiration for the character of Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol. Dickens made reference to Elwes some years later in his last novel, Our Mutual Friend. Elwes was also believed to inspire William Harrison Ainsworth to create the character of John Scarfe in his novel The Miser's Daughter. Elwes inherited his first fortune from his father who died in 1718 when he was just four years old. Although his mother was left £100,000 in the will (approx. £8,000,000 as of 2010) she reputedly starved herself to death because she was too mean to spend it. With her death, he inherited the family estate including Marcham Park at Marcham in Berkshire (now Oxfordshire), purchased by his father in 1717.

The greatest influence on Elwes' life was his miserly uncle, Sir Harvey Elwes, 2nd Baronet, of Stoke College and MP for Sudbury, whom Elwes obsequiously imitated to gain favor. Sir Harvey prided himself on only spending little more than £110 on himself per annum. The two of them would spend the evening railing against other people's extravagances while they shared a single glass of wine. In 1751, in order to inherit his uncle's estate, he changed his name from Meggot to Elwes. Sir Harvey died on 18 September 1763, bequeathing his entire fortune to his nephew. The net worth of the estate was more than £250,000 (approx. £18,000,000 as of 2010), a figure that continued to grow despite Elwes' inept handling of his finances.

On assuming his uncle's fortune, however, Elwes also assumed his uncle's miserly ways. He went to bed when darkness fell so as to save on candles. He began wearing only ragged clothes, including a beggar's cast-off wig he found in a hedge and wore for two weeks. His clothes were so dilapidated that many mistook him for a common street beggar, and would put a penny into his hand as they passed. To avoid paying for a coach he would walk in the rain, and then sit in wet clothes to save the cost of a fire to dry them. His house was full of expensive furniture but also molding food. He would eat putrefied game before allowing new food to be bought. On one occasion it was said that he ate a moorhen that a rat had pulled from a river. Rather than spend the money for repairs he allowed his spacious country mansion to become uninhabitable.

Daniel Dancer (1716–1794) was a notorious English miser whose life was documented soon after his death and continued in print over the following century. The miser Daniel Dancer was born in Pinner, then a rural area in the county of Middlesex, in 1716. His grandfather and father were both noted in their time as misers, and are only less famous because their accumulation of wealth was less. Daniel was the eldest of four children and inherited the family estate, eighty acres of rich meadow land and an adjoining farm, when his father died in 1736.

Hitherto Dancer had given no manifestation of his miserly instincts, but now, in company with his only sister, who shared his tastes and lived with him as his housekeeper, he commenced a life of the utmost seclusion and most rigid parsimony. His lands were allowed to lie fallow so that the expense of cultivation might be avoided. He took only one meal a day, consisting invariably of a little baked meat and a hard-boiled dumpling, a sufficient quantity of which to last the week was prepared every Saturday night. His clothing consisted mainly of hay bands, which were swathed round his feet for boots and round his body for a coat, but it was his habit to purchase one new shirt every year. And after his sister's death in 1766, he used a fraction of her bequest to buy a second-hand pair of black stockings to put himself in decent mourning.

The miser's only dealing with others arose from the sale of his hay. He was seldom seen, except when he was out gathering logs of wood from the common, or old iron, or sheep's dung under the hedges. To prevent theft, he fastened his door up and got into his house through the upper window, to ascend which he made use of a ladder and drew it up after him. The sole person who could be said to be at all intimately acquainted with the Dancers was a Lady Tempest, the widow of Sir Henry Tempest, a Yorkshire baronet. To this lady Dancer's sister had intended to leave her own private property, but she died before she could sign her will. There then arose a lawsuit among her three brothers as to the distribution of her money, the result of which was that Daniel was awarded two-thirds of the sum on the ground of his having kept her for thirty years.

To fill his sister's place Dancer engaged a servant named Griffiths, whose manner of living was as penurious as his own. The two lived together in Dancer's tumble-down house till the master's death, which took place 30 Sept. 1794. In his last moments he was tended by Lady Tempest, who had shown uniform kindness to the old man, and who was rewarded by being made his sole legatee.

John Elwes (a.k.a. "Elwes the Miser"), MP was a Member of Parliament (MP) in Great Britain for Berkshire (1772–1784) and a noted eccentric and miser, suggested to be an inspiration for the character of Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol. Dickens made reference to Elwes some years later in his last novel, Our Mutual Friend. Elwes was also believed to inspire William Harrison Ainsworth to create the character of John Scarfe in his novel The Miser's Daughter. Elwes inherited his first fortune from his father who died in 1718 when he was just four years old. Although his mother was left £100,000 in the will (approx. £8,000,000 as of 2010) she reputedly starved herself to death because she was too mean to spend it. With her death, he inherited the family estate including Marcham Park at Marcham in Berkshire (now Oxfordshire), purchased by his father in 1717.

The greatest influence on Elwes' life was his miserly uncle, Sir Harvey Elwes, 2nd Baronet, of Stoke College and MP for Sudbury, whom Elwes obsequiously imitated to gain favor. Sir Harvey prided himself on only spending little more than £110 on himself per annum. The two of them would spend the evening railing against other people's extravagances while they shared a single glass of wine. In 1751, in order to inherit his uncle's estate, he changed his name from Meggot to Elwes. Sir Harvey died on 18 September 1763, bequeathing his entire fortune to his nephew. The net worth of the estate was more than £250,000 (approx. £18,000,000 as of 2010), a figure that continued to grow despite Elwes' inept handling of his finances.

On assuming his uncle's fortune, however, Elwes also assumed his uncle's miserly ways. He went to bed when darkness fell so as to save on candles. He began wearing only ragged clothes, including a beggar's cast-off wig he found in a hedge and wore for two weeks. His clothes were so dilapidated that many mistook him for a common street beggar, and would put a penny into his hand as they passed. To avoid paying for a coach he would walk in the rain, and then sit in wet clothes to save the cost of a fire to dry them. His house was full of expensive furniture but also molding food. He would eat putrefied game before allowing new food to be bought. On one occasion it was said that he ate a moorhen that a rat had pulled from a river. Rather than spend the money for repairs he allowed his spacious country mansion to become uninhabitable.

It's interesting to me that, since we've been considering a fairy tale motif, Dickens has not mentioned the most famous of misers, King Midas. Perhaps the moral of that particular story is not one that Boffin or Bella is ready to hear just yet.

It's interesting to me that, since we've been considering a fairy tale motif, Dickens has not mentioned the most famous of misers, King Midas. Perhaps the moral of that particular story is not one that Boffin or Bella is ready to hear just yet. Re: Boffins new, um.... frugal ways, they are in keeping with others I've known, or known of: those who came into fortune as adults, and were either so accustomed to living frugally that they continued to do so when it was no longer necessary, or those who were just so afraid of something happening to their wealth that they counted pennies as if they were poor. I'd be willing to bet this was/is true of many older adults who lived through the Depression, and perhaps some who lost a lot of money in 2008, as well.

But this miserly outlook still seems to be a change in his attitude that occurred after he came into his fortune, and a change, again, for which Dickens has not given us any catalyst or context.

I have not reached these chapters yet. Is this the return of Mr. Wegg since he was last peaking under beds?

I have not reached these chapters yet. Is this the return of Mr. Wegg since he was last peaking under beds? Tomorrow is solar eclipse day and might be a good idea to just stay inside and read.

Kim wrote: "Hello friends,

This week finds us with Bella in Chapter 5 of this book titled "The Golden Dustman Falls Into Bad Company". And being with Bella we will find out what she meant in the previous chap..."

Scrooge has met his match, and then some! Ever since Boffin has become "acquainted with the duties of property" his unlikeability index has soared. It was distressing to read that he equates the buying of a sheep with the buying of a person's time.

I agree with Mary Lou. This change of heart and soul seems to come from nowhere with no motivation. A bit abrupt I'd say, even for Dickens.

In terms of plot advancement, Boffin's new look has helped develop the changing nature and heart of Bella. While she may still cling to her earlier desire for money, the cracks are showing, and getting larger. As Leonard Cohen suggested, as the cracks get bigger more light of insight and compassion begin to be revealed. And the light seems to be illuminating the character of Harmon/Rokesmith. This is good.

This week finds us with Bella in Chapter 5 of this book titled "The Golden Dustman Falls Into Bad Company". And being with Bella we will find out what she meant in the previous chap..."

Scrooge has met his match, and then some! Ever since Boffin has become "acquainted with the duties of property" his unlikeability index has soared. It was distressing to read that he equates the buying of a sheep with the buying of a person's time.

I agree with Mary Lou. This change of heart and soul seems to come from nowhere with no motivation. A bit abrupt I'd say, even for Dickens.

In terms of plot advancement, Boffin's new look has helped develop the changing nature and heart of Bella. While she may still cling to her earlier desire for money, the cracks are showing, and getting larger. As Leonard Cohen suggested, as the cracks get bigger more light of insight and compassion begin to be revealed. And the light seems to be illuminating the character of Harmon/Rokesmith. This is good.

Kim wrote: "Our next chapter is titled "The Golden Dustman Falls Into Worse Company" and I'm wondering how much farther he can fall, then I realize that Silas Wegg is back and I know how much more he can fall...."

Well, it does seem to be somewhat ironic that the author of the book on misers, whose title is longer than any title I've ever seen, is Dickensian. What better name than Merryweather to write about misers? And another miser is named Daniel Dancer! Dickens being channeled again.

I found the structure of this chapter to be interesting. The first part gives us the stories of many famous English misers. Boffin is entranced with these stories and at one point " hungrily" exclaims "let's have some more." I wonder if this could be an allusion to King Midas. The desire for wealth has become so consuming that Boffin seems to ignore everything in his pursuit of stories about misers and wealth. Boffin does not see the disagreeable, indeed grotesque actions of the people in the stories he hears, he only sees the glory of the wealth. Also, the title of the chapter is "The Golden Dustman Falls into Worse Company." The title does suggest King Midas.

While Midas was the author of his own downfall perhaps there is a parallel between Boffin and Midas in that both do not see the folly of their ways. Both suffer greatly because this blindness. Boffin may not have suffered too much yet, but it appears that Wegg and Venus are quite prepared to cause his downfall.

Well, it does seem to be somewhat ironic that the author of the book on misers, whose title is longer than any title I've ever seen, is Dickensian. What better name than Merryweather to write about misers? And another miser is named Daniel Dancer! Dickens being channeled again.

I found the structure of this chapter to be interesting. The first part gives us the stories of many famous English misers. Boffin is entranced with these stories and at one point " hungrily" exclaims "let's have some more." I wonder if this could be an allusion to King Midas. The desire for wealth has become so consuming that Boffin seems to ignore everything in his pursuit of stories about misers and wealth. Boffin does not see the disagreeable, indeed grotesque actions of the people in the stories he hears, he only sees the glory of the wealth. Also, the title of the chapter is "The Golden Dustman Falls into Worse Company." The title does suggest King Midas.

While Midas was the author of his own downfall perhaps there is a parallel between Boffin and Midas in that both do not see the folly of their ways. Both suffer greatly because this blindness. Boffin may not have suffered too much yet, but it appears that Wegg and Venus are quite prepared to cause his downfall.

Just a rambling thought ...

We have read novels of Dickens that allegedly model some of his fictional characters on people Dickens knew and also seen references to real people of history scattered throughout his novels.

In OMF, however, in this week's chapter readings there are multiple references to people who did exist. I realize these various misers are not major figures of British history or friends of Dickens. I cannot ever recall, however, so many "real" people being referenced in any other novel, and certainly not so compacted into a few chapters.

Is this something new for Dickens? Is it of any importance? Personally, I don't see it as signaling anything major or different in his style. Still, it's interesting to note out of curiosity.

We have read novels of Dickens that allegedly model some of his fictional characters on people Dickens knew and also seen references to real people of history scattered throughout his novels.

In OMF, however, in this week's chapter readings there are multiple references to people who did exist. I realize these various misers are not major figures of British history or friends of Dickens. I cannot ever recall, however, so many "real" people being referenced in any other novel, and certainly not so compacted into a few chapters.

Is this something new for Dickens? Is it of any importance? Personally, I don't see it as signaling anything major or different in his style. Still, it's interesting to note out of curiosity.

I was particularly shocked when Mr Boffin said that a poor man has nothing to be proud about, all the more so as he himself used to be poor before he stepped into his inheritence. Was he, then, not proud of his kind, understanding and warm-hearted wife? Or of the faithful service he rendered his master? Or of how they looked after the neglected children of their master? I should think that Mr Boffin should be able to remember from his own life that a proud man can have a lot of things to be proud of.

Apart from that, I don't know why a rich man should be proud of his riches in any case. I can understand this as long as the wealth is the result of hard work, or a brilliant idea that one managed to make money of (as long as it was honestly got) - but riches as a result of an inheritence, why should you be proud of them? They are not of your own making, and they give you as much reason to be proud of them as though you had won them in a lottery.

Look at that sentence from whatever angle you will, it is both brain- and heartless. There is only one good thing that I can see in Mr Boffin's change of character - and that is its likelihood to act as a mirror for Bella of what could happen to her if she allows her mercenary calculations to get the better of her. Maybe, Mr Boffin's decline and fall (what a coincidence) will prevent Bella from becoming what she calls "a mercenary wretch" herself.

Apart from that, I don't know why a rich man should be proud of his riches in any case. I can understand this as long as the wealth is the result of hard work, or a brilliant idea that one managed to make money of (as long as it was honestly got) - but riches as a result of an inheritence, why should you be proud of them? They are not of your own making, and they give you as much reason to be proud of them as though you had won them in a lottery.

Look at that sentence from whatever angle you will, it is both brain- and heartless. There is only one good thing that I can see in Mr Boffin's change of character - and that is its likelihood to act as a mirror for Bella of what could happen to her if she allows her mercenary calculations to get the better of her. Maybe, Mr Boffin's decline and fall (what a coincidence) will prevent Bella from becoming what she calls "a mercenary wretch" herself.

Mr Boffin's obsession with misers also shows his lack of judgment, I'd say because there is hardly a person as illogical as a downright miser: A miser has a lot of money and yet lives as miserably as a poor man, and I can't see any point in doing that.

A similar lack of logic, brought about by greed, can be seen in Silas Wegg's calculations of how much money he is going to extort from Mr Boffin. At first, he seems to be content with calling it halves, but by and by, his ideas of how much money he is going to get out of his benefactor are getting out of hand, or brain, and he finally wants it all - only to realize that there would be no point for Mr Boffin in making such a bargain because he would also end up with nothing if he did not buy the friendly movers' silence. Here it can be seen how the lust for money disables people from thinking clearly.

As to Silas talking about Uncle Parker and all those other imaginary inhabitants of "our house", this is probably some kind of self-illusion on his part to hide his own greed from himself. He can always tell himself that he does not want to get one over on Mr Boffin out of greed but out of a feeling of vindicating the former owners of the house - whysoever they should need being vindicated.

A further interesting detail is that Mr Venus's love interest is none other but Pleasant Riderhood. Finally Mr Dickens is linking some plot strands here, by bringing some of his characters together (at least potentially).

A similar lack of logic, brought about by greed, can be seen in Silas Wegg's calculations of how much money he is going to extort from Mr Boffin. At first, he seems to be content with calling it halves, but by and by, his ideas of how much money he is going to get out of his benefactor are getting out of hand, or brain, and he finally wants it all - only to realize that there would be no point for Mr Boffin in making such a bargain because he would also end up with nothing if he did not buy the friendly movers' silence. Here it can be seen how the lust for money disables people from thinking clearly.

As to Silas talking about Uncle Parker and all those other imaginary inhabitants of "our house", this is probably some kind of self-illusion on his part to hide his own greed from himself. He can always tell himself that he does not want to get one over on Mr Boffin out of greed but out of a feeling of vindicating the former owners of the house - whysoever they should need being vindicated.

A further interesting detail is that Mr Venus's love interest is none other but Pleasant Riderhood. Finally Mr Dickens is linking some plot strands here, by bringing some of his characters together (at least potentially).

Peter wrote: "Just a rambling thought ...

Peter wrote: "Just a rambling thought ...We have read novels of Dickens that allegedly model some of his fictional characters on people Dickens knew and also seen references to real people of history scattered..."

That's a very interesting thought, Peter. I have not read enough of the Dickens' canon to know, but surely given this was considered by many his most "modern" novel, then it would not surprise me that it would be populated by such characters as compared to earlier works. As for the one full novel I have read, Great Expectations, I don't recall a similar influx.

There is Barnaby Rudge as another novel in which Dickens makes use of real-life characters but apart from that I cannot right now think of another example. Apart, of course, from the disguised characters such as Skimpole.

But wait, did Dickens not say that the Cheeryble brothers really existed? Kim posted something to this effect once.

Tristram wrote: "There is Barnaby Rudge as another novel in which Dickens makes use of real-life characters but apart from that I cannot right now think of another example. Apart, of course, from the disguised char..."

Tristram wrote: "There is Barnaby Rudge as another novel in which Dickens makes use of real-life characters but apart from that I cannot right now think of another example. Apart, of course, from the disguised char..."This discussion reminds me of a section of Omeros, the great epic poem by Derek Walcott. In terms of characters real, or characters based upon, Walcott may take the cake. He wrote himself into his story, and in fact when one of his characters dies, he attends the funeral for his character!

Which reminds me of Immermann's Münchhausen, where the author also writes himself into the story in order to save his protagonist from his pursuers.

Tristram wrote: "Which reminds me of Immermann's Münchhausen, where the author also writes himself into the story in order to save his protagonist from his pursuers."

Tristram wrote: "Which reminds me of Immermann's Münchhausen, where the author also writes himself into the story in order to save his protagonist from his pursuers."I think a lot of Latin American novelists were notable for this, or similar narrative ploys, and considered Dickens the example they followed, if not in exactness, in spirit at least.

The thing that impressed on me in these chapters was the creepiness of Mr Venus's character. I didn't think that Silas would get out of his place in one piece. Mr Venus, all of a sudden, became a nasty piece of work having seemed to be such a mellow soul just before

The thing that impressed on me in these chapters was the creepiness of Mr Venus's character. I didn't think that Silas would get out of his place in one piece. Mr Venus, all of a sudden, became a nasty piece of work having seemed to be such a mellow soul just before

Let's just say Mr Venus is a zealous adept of his art :-) I had the feeling all along that our noble and tender-hearted Mr Wegg should think twice before trusting such a morbid man. If it goes on like that, our literary friend will have no leg to stand on.

Tristram wrote: "Let's just say Mr Venus is a zealous adept of his art :-) I had the feeling all along that our noble and tender-hearted Mr Wegg should think twice before trusting such a morbid man. If it goes on l..."

Wonderful pun Tristram. I've started my day with a smile. :-))

Wonderful pun Tristram. I've started my day with a smile. :-))

Tristram wrote: "But wait, did Dickens not say that the Cheeryble brothers really existed? Kim posted something to this effect once."

From the second Preface:

One other quotation from the same Preface may serve to introduce a fact that my readers may think curious.

“To turn to a more pleasant subject, it may be right to say, that there are two characters in this book which are drawn from life. It is remarkable that what we call the world, which is so very credulous in what professes to be true, is most incredulous in what professes to be imaginary; and that, while, every day in real life, it will allow in one man no blemishes, and in another no virtues, it will seldom admit a very strongly-marked character, either good or bad, in a fictitious narrative, to be within the limits of probability. But those who take an interest in this tale, will be glad to learn that the Brothers Cheeryble live; that their liberal charity, their singleness of heart, their noble nature, and their unbounded benevolence, are no creations of the Author’s brain; but are prompting every day (and oftenest by stealth) some munificent and generous deed in that town of which they are the pride and honour.”

If I were to attempt to sum up the thousands of letters, from all sorts of people in all sorts of latitudes and climates, which this unlucky paragraph brought down upon me, I should get into an arithmetical difficulty from which I could not easily extricate myself. Suffice it to say, that I believe the applications for loans, gifts, and offices of profit that I have been requested to forward to the originals of the Brothers Cheeryble (with whom I never interchanged any communication in my life) would have exhausted the combined patronage of all the Lord Chancellors since the accession of the House of Brunswick, and would have broken the Rest of the Bank of England.

The Brothers are now dead.

From the second Preface:

One other quotation from the same Preface may serve to introduce a fact that my readers may think curious.

“To turn to a more pleasant subject, it may be right to say, that there are two characters in this book which are drawn from life. It is remarkable that what we call the world, which is so very credulous in what professes to be true, is most incredulous in what professes to be imaginary; and that, while, every day in real life, it will allow in one man no blemishes, and in another no virtues, it will seldom admit a very strongly-marked character, either good or bad, in a fictitious narrative, to be within the limits of probability. But those who take an interest in this tale, will be glad to learn that the Brothers Cheeryble live; that their liberal charity, their singleness of heart, their noble nature, and their unbounded benevolence, are no creations of the Author’s brain; but are prompting every day (and oftenest by stealth) some munificent and generous deed in that town of which they are the pride and honour.”

If I were to attempt to sum up the thousands of letters, from all sorts of people in all sorts of latitudes and climates, which this unlucky paragraph brought down upon me, I should get into an arithmetical difficulty from which I could not easily extricate myself. Suffice it to say, that I believe the applications for loans, gifts, and offices of profit that I have been requested to forward to the originals of the Brothers Cheeryble (with whom I never interchanged any communication in my life) would have exhausted the combined patronage of all the Lord Chancellors since the accession of the House of Brunswick, and would have broken the Rest of the Bank of England.

The Brothers are now dead.

The Bibliomania of the Golden Dustman

Book 3 Chapter 5

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 3, "A Long Lane," Chapter 5, "The Golden Dustman Falls into Bad Company" in Charles Dickens's Our Mutual friend dramatizes Boffin's apparent obsession with acquiring stories of misers' lives, which he purchases without regard to 'size, price or quality', providing that the volume concerns "Anecdotes of strange characters, Records of remarkable individuals." In fact, his "mania" is part of a calculated plan to show Bella Wilfer the folly of her materialism — and the value of the faithful John Rokesmith. Standing next to Mr. Boffin, "The Golden Dustman," at a sidewalk bookstall in Stone's illustration is Bella, a juxtaposition which implies that the moment realized is this, even if the books that the pair wish to examine are in a stall rather than the window of a bookshop:

The moment she pointed out any book as being entitled Lives of eccentric personages, Anecdotes of strange characters, Records of remarkable individuals, or anything to that purpose, Mr. Boffin's countenance would light up, and he would instantly dart in and buy it. Size, price, quality, were of no account. Any book that seemed to promise a chance of miserly biography, Mr. Boffin purchased without a moment's delay and carried home. Happening to be informed by a bookseller that a portion of the Annual Register was devoted to 'Characters,' Mr. Boffin at once bought a whole set of that ingenious compilation, and began to carry it home piecemeal, confiding a volume to Bella, and bearing three himself. The completion of this labour occupied them about a fortnight. When the task was done, Mr. Boffin, with his appetite for Misers whetted instead of satiated, began to look out again.

It very soon became unnecessary to tell Bella what to look for, and an understanding was established between her and Mr Boffin that she was always to look for Lives of Misers. Morning after morning they roamed about the town together, pursuing this singular research. Miserly literature not being abundant, the proportion of failures to successes may have been as a hundred to one; still Mr. Boffin, never wearied, remained as avaricious for misers as he had been at the first onset. It was curious that Bella never saw the books about the house, nor did she ever hear from Mr. Boffin one word of reference to their contents. He seemed to save up his Misers as they had saved up their money. As they had been greedy for it, and secret about it, and had hidden it, so he was greedy for them, and secret about them, and hid them. But beyond all doubt it was to be noticed, and was by Bella very clearly noticed, that, as he pursued the acquisition of those dismal records with the ardour of Don Quixote for his books of chivalry, he began to spend his money with a more sparing hand. And often when he came out of a shop with some new account of one of those wretched lunatics, she would almost shrink from the sly dry chuckle with which he would take her arm again and trot away. It did not appear that Mrs. Boffin knew of this taste. He made no allusion to it, except in the morning walks when he and Bella were always alone; and Bella, partly under the impression that he took her into his confidence by implication, and partly in remembrance of Mrs. Boffin's anxious face that night, held the same reserve.

Feigning to be intent on her embroidery, she sat plying her needle until her busy hand was stopped by Mrs. Boffin's hand being lightly laid upon it

Book 3 Chapter 5

J. Mahoney

1875 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Have you given notice to quit your lodgings?"

"Under your direction, I have, sir."

"Then I tell you what," said Mr. Boffin; "pay the quarter's rent — pay the quarter's rent, it'll be the cheapest thing in the end — and come here at once, so that you may be always on the spot, day and night, and keep the expenses down. You'll charge the quarter's rent to me, and we must try and save it somewhere. You've got some lovely furniture; haven't you?"

"The furniture in my rooms is my own."

"Then we shan't have to buy any for you. In case you was to think it," said Mr. Boffin, with a look of peculiar shrewdness, "so honourably independent in you as to make it a relief to your mind, to make that furniture over to me in the light of a set-off against the quarter's rent, why ease your mind, ease your mind. I don't ask it, but I won't stand in your way if you should consider it due to yourself. As to your room, choose any empty room at the top of the house."

"Any empty room will do for me," said the Secretary.

"You can take your pick," said Mr Boffin, "and it'll be as good as eight or ten shillings a week added to your income. I won't deduct for it; I look to you to make it up handsomely by keeping the expenses down. Now, if you'll show a light, I'll come to your office-room and dispose of a letter or two."

"On that clear, generous face of Mrs. Boffin's, Bella had seen such traces of a pang at the heart while this dialogue was being held, that she had not the courage to turn her eyes to it when they were left alone. Feigning to be intent on her embroidery, she sat plying her needle until her busy hand was stopped by Mrs. Boffin's hand being lightly laid upon it. Yielding to the touch, she felt her hand carried to the good soul's lips, and felt a tear fall on it.

"Oh, my loved husband!" said Mrs Boffin. "This is hard to see and hear. But my dear Bella, believe me that in spite of all the change in him, he is the best of men."

"He came back, at the moment when Bella had taken the hand comfortingly between her own.

"Eh?" said he, mistrustfully looking in at the door. "What's she telling you?"

"She is only praising you, sir," said Bella.

"Praising me? You are sure? Not blaming me for standing on my own defence against a crew of plunderers, who could suck me dry by driblets? Not blaming me for getting a little hoard together?"

Commentary:

The Harper and Brothers illustration for fifth chapter, "The Golden Dustman Falls into Bad Company," in the third book, "A Long Lane," realizes the end of the scene in the parlor of the Boffin mansion in which the Golden Dustman compels John Rokesmith to give up his rented sitting-room in the Wilfer home, and move into the Boffin household as a full-time functionary, to be available at all times of the day. Bella and Mrs. Boffin both sadly note the change in Mr. Boffin's brusque manner towards Rokesmith and his growing parsimony.

I find from this point on I will have to rearrange the commentary so much to not give away a very important part of the plot, I will be cutting most of the commentary. So I've decided to just post it here with a spoiler alert. I don't understand why the commentators seem to think we've all read the book in the first place. Remember, If you go on to read it please keep it to yourself. My word, I'm almost afraid to post it at all. :-)

(view spoiler)

The Dutch Bottle

Book 3 Chapter 6

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 3, "A Long Lane," Chapter 6, "The Golden Dustman falls into Worse Company," in Charles Dickens's Our Mutual friend appeared in the April 1865, installment. Since it alludes to one of the most celebrated aspects and central symbols of the novel, Boffin's dust-heaps, Dickens selected it as the frontispiece for the second volume of the November 1865 Chapman and Hall edition. Silas Wegg and his companion, the taxidermist, Mr. Venus, having participated in an oral reading for Mr. Boffin, surreptitiously follow him out to the mounds in hopes of learning where he has secreted his treasure. The passage which culminates in Noddy Boffin's unearthing the Dutch bottle is as follows:

At a nimbler trot, as if the shovel over his shoulder stimulated him by reviving old associations, Mr. Boffin ascended the 'serpentining walk', up the Mound which he had described to Silas Wegg on the occasion of their beginning to decline and fall. On striking into it he turned his lantern off. The two followed him, stooping low, so that their figures might make no mark in relief against the sky when he should turn his lantern on again. Mr. Venus took the lead, towing Mr. Wegg, in order that his refractory leg might be promptly extricated from any pitfalls it should dig for itself. They could just make out that the Golden Dustman stopped to breathe. Of course they stopped too, instantly.

'This is his own Mound,' whispered Wegg, as he recovered his wind, 'this one.

'Why all three are his own,' returned Venus.

'So he thinks; but he's used to call this his own, because it's the one first left to him; the one that was his legacy when it was all he took under the will.'

'When he shows his light,' said Venus, keeping watch upon his dusky figure all the time, 'drop lower and keep closer.'

He went on again, and they followed again. Gaining the top of the Mound, he turned on his light — but only partially — and stood it on the ground. A bare lopsided weather-beaten pole was planted in the ashes there, and had been there many a year. Hard by this pole, his lantern stood: lighting a few feet of the lower part of it and a little of the ashy surface around, and then casting off a purposeless little clear trail of light into the air.

'He can never be going to dig up the pole!' whispered Venus as they dropped low and kept close.

'Perhaps it's holler and full of something,' whispered Wegg.

He was going to dig, with whatsoever object, for he tucked up his cuffs and spat on his hands, and then went at it like an old digger as he was. He had no design upon the pole, except that he measured a shovel's length from it before beginning, nor was it his purpose to dig deep. Some dozen or so of expert strokes sufficed. Then, he stopped, looked down into the cavity, bent over it, and took out what appeared to be an ordinary case-bottle: one of those squat, high-shouldered, short-necked glass bottles which the Dutchman is said to keep his Courage in. As soon as he had done this, he turned off his lantern, and they could hear that he was filling up the hole in the dark. The ashes being easily moved by a skilful hand, the spies took this as a hint to make off in good time.

The precise moment that Stone has realized is Boffin's abstracting the bottle from the mound, but immediately before he turns off his lantern (off right). All the other elements of the scene as described in the text are present: the watchers, Wegg and Venus, in the background; and Boffin's shovel, pole, and Dutch bottle. Although Stone has satisfactorily captured the mysteriousness of the scene, using chiaroscuro effectively, the central figure, Nicodemus Boffin, looks nothing much like the portly, middle-aged gentleman of such earlier plates as "Bibliomania of the Golden Dustman" (the other April 1865 illustration).

The physical setting, which Dickens does not specify, is a busy London street — as one may see by the carriages, multi-story buildings, and church spire in the background. Such is the verisimilitude that Stone may have used an actual street scene as the basis for the illustration, but could not have been the Portebello Road Market, which began in the late 1860s. Logically, the urban setting is either Cheapside, near St. Paul's (site of many publishing houses since the Renaissance), or the Strand, to which London's booksellers were gravitating in the middle of the nineteenth century.

"He can never be going to dig up that pole!" whispered Venus as they dropped low and kept close.

Book 3 Chapter 6

J. Mahoney

1875 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"This is his own Mound," whispered Wegg, as he recovered his wind, "this one."

"Why all three are his own," returned Venus.

"So he thinks; but he's used to call this his own, because it's the one first left to him; the one that was his legacy when it was all he took under the will."

"When he shows his light," said Venus, keeping watch upon his dusky figure all the time, "drop lower and keep closer."

He went on again, and they followed again. Gaining the top of the Mound, he turned on his light — but only partially — and stood it on the ground. A bare lopsided weather beaten pole was planted in the ashes there, and had been there many a year. Hard by this pole, his lantern stood: lighting a few feet of the lower part of it and a little of the ashy surface around, and then casting off a purposeless little clear trail of light into the air.

"He can never be going to dig up the pole!" whispered Venus as they dropped low and kept close.

"Perhaps it's holler and full of something," whispered Wegg.

He was going to dig, with whatsoever object, for he tucked up his cuffs and spat on his hands, and then went at it like an old digger as he was. He had no design upon the pole, except that he measured a shovel's length from it before beginning, nor was it his purpose to dig deep. Some dozen or so of expert strokes sufficed. Then, he stopped, looked down into the cavity, bent over it, and took out what appeared to be an ordinary case-bottle: one of those squat, high-shouldered, short-necked glass bottles which the Dutchman is said to keep his Courage in.

Commentary:

The Harper and Brothers woodcut for the third book's sixth chapter, "The Golden Dustman Falls into Worse Company," concerns Venus and Wegg's following Boffin to the Mounds late one evening. They watch him dig up a bottle, then subsequently learn from him that he has just sold the Mounds, and that their removal will commence on the following morning.

Since it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney's 1875 treatment of the textual material is often a response to the original series of illustrations by Marcus Stone, Dickens's original serial and volume illustrator. Although Mahoney sometimes rejects Stone's notions, in The Dutch Bottle, one of three illustrations for the April 1865 or twelfth monthly part in the British serialization, the Household Edition illustrator reorganized the equivalent Stone illustration, foregrounding the watchers and positioning Boffin well to the rear, so that the viewer takes in the scene from the watchers' perspective, just as the text does. And Mahoney takes the opportunity to depict the apocalyptic wasteland that the mounds constitute, associating death and decay with wealth. Whereas American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr. in the 1867 Diamond Edition sequence chose to depict the relationship between Silas Wegg and Mr. Venus only in terms of the latter's taxidermy shop in Mr. Wegg and Mr. Venus in Consultation, James Mahoney has elected to depict these characters in a highly dramatic moment. Although his style and treatment are not as elegant as the initial photogravure frontispiece by Felix Octavius Carr Darley, Mr. Boffin engages Mr. Wegg in 1866, the Mahoney illustration of the next decade achieves a certain atmosphere of suspicion and anticipation that is a crucial aspect of this novel, weaving together the plot strands of avarice, mistrust, surveillance, and conspiracy.

The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin

Book 3 Chapter 7

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration appeared in the May 1865, installment. Wegg, made bitterly envious of Boffin's good fortune after the incident at the mounds (previous illustration) and determined to separate the Golden Dustman from most of his inheritance by virtue of the alternate Harmon will which he has discovered and verified through the registry at Doctors' Commons, nightly haunts the vicinity of the Boffin town house, its classical pillars (supplied like much of the scene by Stone rather than Dickens) implying the owner's power and affluence.

Only the anonymity afforded him by the cover of darkness prevents his being noticed, for his peg-leg generally renders him as conspicuous in such a neighborhood as his battered hat renders him ridiculous. As he watches the arrival of the Boffins' carriage, symbolic of their superior social status and wealth, in the lighted area of the stately mansion's port cocherie, Wegg, smiling to himself and studying the fashionably gowned Bella Wilfer as she passes through the entrance way, styles himself "The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin," as if he were an avenging spirit from Poe or Collins:

For, Silas Wegg felt it to be quite out of the question that he could lay his head upon his pillow in peace, without first hovering over Mr. Boffin's house in the superior character of its Evil Genius. Power (unless it be the power of intellect or virtue) has ever the greatest attraction for the lowest natures; and the mere defiance of the unconscious house-front, with his power to strip the roof off the inhabiting family like the roof of a house of cards, was a treat which had a charm for Silas Wegg.

As he hovered on the opposite side of the street, exulting, the carriage drove up.

'There'll shortly be an end of you,' said Wegg, threatening it with the hat-box. 'Your varnish is fading.'

Mrs. Boffin descended and went in.

'Look out for a fall, my Lady Dustwoman,' said Wegg.

Bella lightly descended, and ran in after her.

'How brisk we are!' said Wegg. 'You won't run so gaily to your old shabby home, my girl. You'll have to go there, though.'

In Wegg's right hand Stone has placed the hat-box which had contained the alternate will with which Wegg plans to blackmail Boffin. His feeling so confident in his ability to use the new Harmon will as leverage against Boffin is ironic in that he has entrusted the document to Venus, who has already proven less than completely trustworthy. Shortly Boffin's shadow will appear against the blinds of the three lighted windows in the second story.

.....Just in case you were wondering why there are three illustrations this week instead of the usual four (which I was for some time), the second illustration, "The Dutch Bottle" was the title page of this book.

"There'll shortly be an end of you," said Wegg, threatening it with the hat-box. Your varnish is fading.

Book 3 Chapter 7

J. Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

After Silas had left the shop, hat-box in hand, and had left Mr. Venus to lower himself to oblivion-point with the requisite weight of tea, it greatly preyed on his ingenuous mind that he had taken this artist into partnership at all. He bitterly felt that he had overreached himself in the beginning, by grasping at Mr. Venus's mere straws of hints, now shown to be worthless for his purpose. Casting about for ways and means of dissolving the connexion without loss of money, reproaching himself for having been betrayed into an avowal of his secret, and complimenting himself beyond measure on his purely accidental good luck, he beguiled the distance between Clerkenwell and the mansion of the Golden Dustman.

For, Silas Wegg felt it to be quite out of the question that he could lay his head upon his pillow in peace, without first hovering over Mr Boffin's house in the superior character of its Evil Genius. Power (unless it be the power of intellect or virtue) has ever the greatest attraction for the lowest natures; and the mere defiance of the unconscious house-front, with his power to strip the roof off the inhabiting family like the roof of a house of cards, was a treat which had a charm for Silas Wegg.

As he hovered on the opposite side of the street, exulting, the carriage drove up.

"There'll shortly be an end of you," said Wegg, threatening it with the hat-box. "Your varnish is fading."

Mrs. Boffin descended and went in.

"Look out for a fall, my Lady Dustwoman," said Wegg.

Bella lightly descended, and ran in after her.

"How brisk we are!" said Wegg. "You won't run so gaily to your old shabby home, my girl. You'll have to go there, though."

A little while, and the Secretary came out.

"I was passed over for you," said Wegg. "But you had better provide yourself with another situation, young man."

Mr. Boffin's shadow passed upon the blinds of three large windows as he trotted down the room, and passed again as he went back.

"Yoop!" cried Wegg. "You're there, are you? Where's the bottle? You would give your bottle for my box, Dustman!"

Having now composed his mind for slumber, he turned homeward.

Commentary:

The illustration for the third book's seventh chapter, "The Friendly Move Takes Up a Strong Position," concerns Venus and Wegg's plot to rob Boffin of most of the Harmon fortune by employing the will that Wegg previously discovered in a cashbox in the Mounds:

Regularly executed, regularly witnessed, very short. Inasmuch as he has never made friends, and has ever had a rebellious family, he, John Harmon, gives to Nicodemus Boffin the Little Mound, which is quite enough for him, and gives the whole rest and residue of his property to the Crown."

The scene of the Mahoney illustration is the street outside the Boffin (Harmon) mansion. The hatbox that Wegg waves at Boffin's carriage has added significance, for it is his means of concealing the cashbox containing the will — "an old leathern hat-box, into which he had put the other box, for the better preservation of commonplace appearances, and for the disarming of suspicion."

Since it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney's 1875 treatment of the scene outside the Boffin mansion is best considered in light of the changes in composition and emphasis that he effected upon the Marcus Stone original serial illustration. Although Mahoney sometimes rejects Stone's notions, here as in The Dutch Bottle in the twelfth monthly part, the Household Edition illustrator has borrowed directly from Stone, foregrounding the speaker and throwing a departing figure (presumably that of Mrs. Boffin in the lighted doorway) well to the rear, so that the viewer takes in the scene from the perspective of the envious Silas Wegg, just as the text does. Mahoney's illustration continues to construct an atmosphere of suspicion and anticipation that is crucial at this point in the novel, weaving together the plot strands of avarice, mistrust, surveillance, and conspiracy.

In Mahoney's treatment, Wegg does not merely smile knowingly (as in Stone's version), but shakes the hatbox dismissively at the carriage, symbol of the Boffins' new-found social status in contrast to the disgruntled pedestrian Wegg. Mahoney has positioned Wegg much further away from the carriage, so that, in the darkness, he would probably be invisible to the occupants of the vehicle as it pulls up at the well-lit entrance. Already the carriage is in motion in the 1865 illustration, whereas it is still stopped at the mansion's front door in the 1875 plate, the horses woodenly static. Stone has chosen to emphasize the mansion's brilliantly lit windows and the carriage lantern as emblems of nouveau riche conspicuous consumption, for this is the exalted, luminescent sphere of ease and affluence that envious, malcontented Silas Wegg, in the outer darkness, yearns to enter in his own right and not merely as a servant or employee of the Golden Dustman. Curiously, Mahoney has muted this effect of light versus darkness in favor of foregrounding the figure of Wegg in a pool of light (perhaps implying a street lamp) and, at the bottom of the plate, a sewer-grate, the ruled lines and kerb curving away from Wegg towards the drain, his proper social station.

Kim wrote: "The Bibliomania of the Golden Dustman

Book 3 Chapter 5

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 3, "A Long Lane," Chapter 5, "The Golden Dustman Falls into Bad Company" in Charles..."

Kim

I truly enjoy the weekly illustrations you post for us.

The bookstall illustration is great. It captures the joy of books being sold along the streets of London. The illustration would make a good addition to any book about 19C life. Reading through the other comments on the illustrations below it seems that many of the illustrations were interior scenes. I enjoy the outside illustrations as they capture the flavour of London so well.

Book 3 Chapter 5

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 3, "A Long Lane," Chapter 5, "The Golden Dustman Falls into Bad Company" in Charles..."

Kim

I truly enjoy the weekly illustrations you post for us.

The bookstall illustration is great. It captures the joy of books being sold along the streets of London. The illustration would make a good addition to any book about 19C life. Reading through the other comments on the illustrations below it seems that many of the illustrations were interior scenes. I enjoy the outside illustrations as they capture the flavour of London so well.

Kim wrote: ""He can never be going to dig up that pole!" whispered Venus as they dropped low and kept close.

Book 3 Chapter 6

J. Mahoney

1875 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"This is his own Mound," w..."

Both the Dutch Bottle illustrations reminded me of Treasure Island. Watching the digging up of a treasure, knowing that whatever the object is will be of value, but what exactly is it? ... great suspense and mood.

Rather than an exotic island such as a good pirate story, however, we must remember that this bottle treasure, whatever it may contain, comes from a dust heap, from a pile of materials it best not to think about too much. Still, the mound, as the commentary states, is symbolic of the greed, the avaricious nature and degree to which humans will go to obtain and retain their wealth.

Book 3 Chapter 6

J. Mahoney

1875 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"This is his own Mound," w..."

Both the Dutch Bottle illustrations reminded me of Treasure Island. Watching the digging up of a treasure, knowing that whatever the object is will be of value, but what exactly is it? ... great suspense and mood.

Rather than an exotic island such as a good pirate story, however, we must remember that this bottle treasure, whatever it may contain, comes from a dust heap, from a pile of materials it best not to think about too much. Still, the mound, as the commentary states, is symbolic of the greed, the avaricious nature and degree to which humans will go to obtain and retain their wealth.

Kim wrote: "The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin

Book 3 Chapter 7

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration appeared in the May 1865, installment. Wegg, made bitterly envious of Boffin's good fortune..."

For my favourite illustration of the week the nod goes to "The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin." Great atmosphere, great rendering of the world of Boffin as it contrasts with the world of Wegg. I also enjoyed the commentary interpretation of the scene. The rendering of Bella makes her seem ghostlike, as if she is between two worlds. In fact, I think she is. One the one hand she inhabits the solid world of the Boffin mansion and fortune, but, at the same time, she is caught in between worlds. She is, at once, the Wilfer daughter and the Boffin adopted daughter. She is both attracted to and yet apparently still struggles against her obvious attraction to Rokesmith. Finally, Bella is also becoming more self-conflicted about her feelings towards money and wealth. She is in a nether world.

Book 3 Chapter 7

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration appeared in the May 1865, installment. Wegg, made bitterly envious of Boffin's good fortune..."

For my favourite illustration of the week the nod goes to "The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin." Great atmosphere, great rendering of the world of Boffin as it contrasts with the world of Wegg. I also enjoyed the commentary interpretation of the scene. The rendering of Bella makes her seem ghostlike, as if she is between two worlds. In fact, I think she is. One the one hand she inhabits the solid world of the Boffin mansion and fortune, but, at the same time, she is caught in between worlds. She is, at once, the Wilfer daughter and the Boffin adopted daughter. She is both attracted to and yet apparently still struggles against her obvious attraction to Rokesmith. Finally, Bella is also becoming more self-conflicted about her feelings towards money and wealth. She is in a nether world.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "But wait, did Dickens not say that the Cheeryble brothers really existed? Kim posted something to this effect once."

From the second Preface:

One other quotation from the same Pr..."

Thanks, Kim, for providing the exact reference. I knew there was something along that line, and since we are talking about Nicholas, was not Squeers also modelled on real-life Yorkshire schoolteachers that Dickens did some research on?

From the second Preface:

One other quotation from the same Pr..."

Thanks, Kim, for providing the exact reference. I knew there was something along that line, and since we are talking about Nicholas, was not Squeers also modelled on real-life Yorkshire schoolteachers that Dickens did some research on?

Like Peter, I would give my nod for this week's best illustration to Marcus Stone's "The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin", with "The Dutch Bottle" following closely on its heels.

If you compare Mahoney's illustration of the same bottle scene, I think it becomes clear that Marcus Stone's perspective was the better choice, because it allows him to picture Wegg and Venus as shadow-creatures, looking almost like hobgoblins. On the other hand, Mahoney makes the viewer share the viewpoint of the two conspirators and thereby clings closer to the perspective chosen in the chapter. I'd say, though, that Stone's decision to choose a more neutral, omniscient perspective paradoxically adds to the mysteriousness of the whole situation. You inevitably ask yourself what is in that bottle.

As to the "Evil Genius", I can subscribe to what Peter said, and am still astonished by the clever use of chiaroscuro - this could really be a scene from film noir!