The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 3, Chp. 08-10

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

The following Chapter tells us how “Somebody Becomes the Subject of a Prediction”, and this Somebody is Bella Wilfer. Like the previous chapter, Chapter 9 is more a chapter of organization in that it ties several strands of the novel together, especially by bringing the two main female characters into contact. As I did not particularly enjoy it for any Dickensian qualities, and as it is clearly an “organizational chapter”, as I said, I am going to be brief and systematic about it:

Being notified about Betty’s death – the old lady had, as you may remember, a letter with her with instructions of whom to notify in an emergency –, Mr Rokesmith, Bella, the unavoidable Sloppy and the Milveys arrive on the scene and the Reverend conducts the old lady’s funeral. What I found very moving and decent was that not a penny was spent in addition to what she had saved and hidden in her clothes. So, after all, her wish of paying her own way through life was honoured up to the very end of her life’s journey. Might this wish for independence, even though it meant living and dying on limited means, not be seen as a counter-concept to Mr Boffin’s recent words according to which a poor man (and woman) does not have anything to be proud about? Would Mr Boffin not bend his head in shame and eat his words when he thinks of the example set by old Betty Higden? And might this example not also teach our Bella something about life and the values you pursue?

We finally learn that Lizzie Hexam is now working in a paper mill and that she has found shelter with friends of Mr Riah. To Reverend Milvey’s dismay, his wife is appalled to find Lizzie in close contact with Jews, and we have the following conversation:

What might be Dickens’s intention behind showing a positively drawn figure such as Mrs Milvey have reservations against Jews? I would say that he wanted to show how widely-spread anti-Jewish prejudices are, and that he wanted his readers to realize that they are just that – prejudices. I especially liked Lizzie’s statement that people can live together on the basis of the agreement that religion is a private thing and that no one should try to make other people adopt his own religion. Given the present situation in Europe, I cannot stress enough how much I liked it.

We also learn that Mr Rokesmith has the commission from his employer to find out whether Lizzie has gone into hiding because of the former accusations directed against her father – a question that he also has a personal interest in –, and he entrusts this commission to Bella, seeing that there is a natural bond of mutual confidence between the two young women. The chapter now centres on a conversation between Lizzie and Bella in which we learn, among other things, that the breach between her brother and herself is now complete but that she does not reproach Charley with anything and hopes that he will get on well in life. We also learn that she has disliked Bradley Headstone from the first time she set eyes on him, and that her fear of him is not so much on behalf of herself but of someone else – you guess, Eugene Wrayburn. Lizzie finally confesses to her love for Eugene – alas! in a typically self-denying and Dickens-like way:

What do you make of all this, my friends? Contrast this paragon of self-denial and forbearance with Bella, who always intersperses the interview with examples of her liveliness and with signs of her being torn between admiration for Lizzie’s purity of heart and her own more calculating thoughts and wishes. I find Bella by far the more interesting character of the two, although I would say that this conversation is very important with regard to her further development towards a more Dickensian ideal of womanhood.

Lizzie plays her old game of looking into the hollow by the flame, this time being a fortune-teller for Bella and pointing out to her that she has a heart of gold. The two women part friends, and on their way home, Rokesmith and Bella feel very close. This chapter, unfortunately, does not end as beautifully as the previous one, because there is, again, some inane boofering.

Being notified about Betty’s death – the old lady had, as you may remember, a letter with her with instructions of whom to notify in an emergency –, Mr Rokesmith, Bella, the unavoidable Sloppy and the Milveys arrive on the scene and the Reverend conducts the old lady’s funeral. What I found very moving and decent was that not a penny was spent in addition to what she had saved and hidden in her clothes. So, after all, her wish of paying her own way through life was honoured up to the very end of her life’s journey. Might this wish for independence, even though it meant living and dying on limited means, not be seen as a counter-concept to Mr Boffin’s recent words according to which a poor man (and woman) does not have anything to be proud about? Would Mr Boffin not bend his head in shame and eat his words when he thinks of the example set by old Betty Higden? And might this example not also teach our Bella something about life and the values you pursue?

We finally learn that Lizzie Hexam is now working in a paper mill and that she has found shelter with friends of Mr Riah. To Reverend Milvey’s dismay, his wife is appalled to find Lizzie in close contact with Jews, and we have the following conversation:

”‘The gentleman certainly is a Jew,’ said Lizzie, ‘and the lady, his wife, is a Jewess, and I was first brought to their notice by a Jew. But I think there cannot be kinder people in the world.’

‘But suppose they try to convert you!’ suggested Mrs Milvey, bristling in her good little way, as a clergyman’s wife.

‘To do what, ma’am?’ asked Lizzie, with a modest smile.

‘To make you change your religion,’ said Mrs Milvey.

Lizzie shook her head, still smiling. ‘They have never asked me what my religion is. They asked me what my story was, and I told them. They asked me to be industrious and faithful, and I promised to be so. They most willingly and cheerfully do their duty to all of us who are employed here, and we try to do ours to them. Indeed they do much more than their duty to us, for they are wonderfully mindful of us in many ways.’

‘It is easy to see you’re a favourite, my dear,’ said little Mrs Milvey, not quite pleased.

‘It would be very ungrateful in me to say I am not,’ returned Lizzie, ‘for I have been already raised to a place of confidence here. But that makes no difference in their following their own religion and leaving all of us to ours. They never talk of theirs to us, and they never talk of ours to us. If I was the last in the mill, it would be just the same. They never asked me what religion that poor thing had followed.’”

What might be Dickens’s intention behind showing a positively drawn figure such as Mrs Milvey have reservations against Jews? I would say that he wanted to show how widely-spread anti-Jewish prejudices are, and that he wanted his readers to realize that they are just that – prejudices. I especially liked Lizzie’s statement that people can live together on the basis of the agreement that religion is a private thing and that no one should try to make other people adopt his own religion. Given the present situation in Europe, I cannot stress enough how much I liked it.

We also learn that Mr Rokesmith has the commission from his employer to find out whether Lizzie has gone into hiding because of the former accusations directed against her father – a question that he also has a personal interest in –, and he entrusts this commission to Bella, seeing that there is a natural bond of mutual confidence between the two young women. The chapter now centres on a conversation between Lizzie and Bella in which we learn, among other things, that the breach between her brother and herself is now complete but that she does not reproach Charley with anything and hopes that he will get on well in life. We also learn that she has disliked Bradley Headstone from the first time she set eyes on him, and that her fear of him is not so much on behalf of herself but of someone else – you guess, Eugene Wrayburn. Lizzie finally confesses to her love for Eugene – alas! in a typically self-denying and Dickens-like way:

”‘I should lose some of the best recollections, best encouragements, and best objects, that I carry through my daily life. I should lose my belief that if I had been his equal, and he had loved me, I should have tried with all my might to make him better and happier, as he would have made me. I should lose almost all the value that I put upon the little learning I have, which is all owing to him, and which I conquered the difficulties of, that he might not think it thrown away upon me. I should lose a kind of picture of him—or of what he might have been, if I had been a lady, and he had loved me—which is always with me, and which I somehow feel that I could not do a mean or a wrong thing before. I should leave off prizing the remembrance that he has done me nothing but good since I have known him, and that he has made a change within me, like—like the change in the grain of these hands, which were coarse, and cracked, and hard, and brown when I rowed on the river with father, and are softened and made supple by this new work as you see them now.’

They trembled, but with no weakness, as she showed them.

‘Understand me, my dear;’ thus she went on. ‘I have never dreamed of the possibility of his being anything to me on this earth but the kind picture that I know I could not make you understand, if the understanding was not in your own breast already. I have no more dreamed of the possibility of my being his wife, than he ever has—and words could not be stronger than that. And yet I love him. I love him so much, and so dearly, that when I sometimes think my life may be but a weary one, I am proud of it and glad of it. I am proud and glad to suffer something for him, even though it is of no service to him, and he will never know of it or care for it.’”

What do you make of all this, my friends? Contrast this paragon of self-denial and forbearance with Bella, who always intersperses the interview with examples of her liveliness and with signs of her being torn between admiration for Lizzie’s purity of heart and her own more calculating thoughts and wishes. I find Bella by far the more interesting character of the two, although I would say that this conversation is very important with regard to her further development towards a more Dickensian ideal of womanhood.

Lizzie plays her old game of looking into the hollow by the flame, this time being a fortune-teller for Bella and pointing out to her that she has a heart of gold. The two women part friends, and on their way home, Rokesmith and Bella feel very close. This chapter, unfortunately, does not end as beautifully as the previous one, because there is, again, some inane boofering.

The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out”, and Dickens would not not be Dickens if you could not understand the title of this chapter in at least two different ways. We are directly dropped into a conversation between Eugene Wrayburn and Jenny Wren, with her drunken father lingering in the background and being subject to Jenny’s continual reprimands. It’s obvious that Eugene’s object is to worm some information about Lizzie’s whereabouts out of Jenny, and it’s a delight to see how cleverly she parries each of his attempts at doing so:

Thinking of our recent Eugene-Wilde discussion, did not one of Wilde’s characters in The Importance of Being Ernest have a fictitious friend or uncle in the country, whom he always visits when he is bored by society?

Since Jenny has to go to work, she more or less chucks Eugene out of her house, and when sauntering more or less aimlessly through the streets of London, with his inevitable cigar – he even lights his cigar in Jenny’s presence (I remark this because I read somewhere that a Victorian gentleman would never have smoked a cigar in the presence of a woman, and so this can be seen as another sign of Eugene’s disdain and carelessness – I just hate the guts of that fellow and make a point of listing all of his shortcomings) –, Eugene happens to see Jenny’s father, who is utterly drunk and in vain tries to cross a street. Not thinking much about it, Eugene enters his and Mortimer’s lodgings, and finding his friend there, the two of them start a conversation in the course of which it becomes clear that Eugene has run into debts with Fledgeby (probably one of the purchases of debts that fascinating youth made), although Mortimer, of course, thinks that Mr Riah is the creditor. Mortimer is not free of prejudice in that one of the associations he makes is connected with Shakespeare’s money-lender Shylock. Wrayburn, as usual, makes light of the whole matter and is definitely content with knowing that he will not be able to settle his debts with Mr Riah – although he says that he thinks that gentleman will be all the more eager to press him because he also seems to have had a hand in making Lizzie “disappear”. Their talk thus centres on Lizzie, and Mortimer states that sooner or later, everything Eugene is doing or thinking of runs down to Lizzie. Eugene does not deny this and, instead, stresses his determination to find her – be it, as he says, by fair means or foul. He even goes so far as to regard his obsession with Lizzie as a merit in that it shows that he can be determined and earnest about something, for a change.

Their conversation is interrupted by the appearance of Jenny’s father, who wants to strike a bargain with Eugene. For fifteen shillings – to be turned into rum – the drunkard offers to find out the address where Lizzie can be found by prying into his daughter’s correspondence. Wrayburn not only does not hesitate a second to make use of this shabby opportunity but he also treats the drunken man with utmost disdain – by “fumigating” him and by offering him something to drink to loosen his tongue. He also slips into his habit of inventing names for other people – remember that he did not even bother to find out Mr Riah’s real name but just calls him Mr Aaron – in that he dubs Jenny’s father Mr Dolls. By the way, what do you make of Eugene’s habit of inventing names for other people?

After sending his own scout out – a decision that even his friend Mortimer is shocked at –, Wrayburn confides to Mortimer that he himself is the object of scouts whenever he leaves his house at night. There is always Bradley Headstone clinging at his heels, and sometimes he is accompanied by Charley Hexam. Wrayburn derives some sort of mean pleasure from this situation:

He assumes that he is being followed because Headstone thinks that sooner or later he will lead him to Lizzie, but maybe that is not the only object the jealous and frenzied schoolmaster has in mind? In order to distract his friend from the unpleasant interview with Jenny’s father and its even more unpleasant outcome, Wrayburn takes Mortimer for a stroll to show him how obstinately Bradley clings to his heels. It does not take long before the two really spot the teacher, and Eugene, of course, does not lose this opportunity to humiliate Bradley. All this is not suited to alloy the worries Mortimer feels with regard to the whole situation.

” ‘And my charming young goddaughter,’ said Mr Wrayburn plaintively, ‘down in Hertfordshire—’

(‘Humbugshire you mean, I think,’ interposed Miss Wren.)”

Thinking of our recent Eugene-Wilde discussion, did not one of Wilde’s characters in The Importance of Being Ernest have a fictitious friend or uncle in the country, whom he always visits when he is bored by society?

Since Jenny has to go to work, she more or less chucks Eugene out of her house, and when sauntering more or less aimlessly through the streets of London, with his inevitable cigar – he even lights his cigar in Jenny’s presence (I remark this because I read somewhere that a Victorian gentleman would never have smoked a cigar in the presence of a woman, and so this can be seen as another sign of Eugene’s disdain and carelessness – I just hate the guts of that fellow and make a point of listing all of his shortcomings) –, Eugene happens to see Jenny’s father, who is utterly drunk and in vain tries to cross a street. Not thinking much about it, Eugene enters his and Mortimer’s lodgings, and finding his friend there, the two of them start a conversation in the course of which it becomes clear that Eugene has run into debts with Fledgeby (probably one of the purchases of debts that fascinating youth made), although Mortimer, of course, thinks that Mr Riah is the creditor. Mortimer is not free of prejudice in that one of the associations he makes is connected with Shakespeare’s money-lender Shylock. Wrayburn, as usual, makes light of the whole matter and is definitely content with knowing that he will not be able to settle his debts with Mr Riah – although he says that he thinks that gentleman will be all the more eager to press him because he also seems to have had a hand in making Lizzie “disappear”. Their talk thus centres on Lizzie, and Mortimer states that sooner or later, everything Eugene is doing or thinking of runs down to Lizzie. Eugene does not deny this and, instead, stresses his determination to find her – be it, as he says, by fair means or foul. He even goes so far as to regard his obsession with Lizzie as a merit in that it shows that he can be determined and earnest about something, for a change.

Their conversation is interrupted by the appearance of Jenny’s father, who wants to strike a bargain with Eugene. For fifteen shillings – to be turned into rum – the drunkard offers to find out the address where Lizzie can be found by prying into his daughter’s correspondence. Wrayburn not only does not hesitate a second to make use of this shabby opportunity but he also treats the drunken man with utmost disdain – by “fumigating” him and by offering him something to drink to loosen his tongue. He also slips into his habit of inventing names for other people – remember that he did not even bother to find out Mr Riah’s real name but just calls him Mr Aaron – in that he dubs Jenny’s father Mr Dolls. By the way, what do you make of Eugene’s habit of inventing names for other people?

After sending his own scout out – a decision that even his friend Mortimer is shocked at –, Wrayburn confides to Mortimer that he himself is the object of scouts whenever he leaves his house at night. There is always Bradley Headstone clinging at his heels, and sometimes he is accompanied by Charley Hexam. Wrayburn derives some sort of mean pleasure from this situation:

”‘Then soberly and plainly, Mortimer, I goad the schoolmaster to madness. I make the schoolmaster so ridiculous, and so aware of being made ridiculous, that I see him chafe and fret at every pore when we cross one another. The amiable occupation has been the solace of my life, since I was baulked in the manner unnecessary to recall. I have derived inexpressible comfort from it. I do it thus: I stroll out after dark, stroll a little way, look in at a window and furtively look out for the schoolmaster. Sooner or later, I perceive the schoolmaster on the watch; sometimes accompanied by his hopeful pupil; oftener, pupil-less. Having made sure of his watching me, I tempt him on, all over London. One night I go east, another night north, in a few nights I go all round the compass. Sometimes, I walk; sometimes, I proceed in cabs, draining the pocket of the schoolmaster who then follows in cabs. I study and get up abstruse No Thoroughfares in the course of the day. With Venetian mystery I seek those No Thoroughfares at night, glide into them by means of dark courts, tempt the schoolmaster to follow, turn suddenly, and catch him before he can retreat. Then we face one another, and I pass him as unaware of his existence, and he undergoes grinding torments. Similarly, I walk at a great pace down a short street, rapidly turn the corner, and, getting out of his view, as rapidly turn back. I catch him coming on post, again pass him as unaware of his existence, and again he undergoes grinding torments. Night after night his disappointment is acute, but hope springs eternal in the scholastic breast, and he follows me again to-morrow. Thus I enjoy the pleasures of the chase, and derive great benefit from the healthful exercise. When I do not enjoy the pleasures of the chase, for anything I know he watches at the Temple Gate all night.’”

He assumes that he is being followed because Headstone thinks that sooner or later he will lead him to Lizzie, but maybe that is not the only object the jealous and frenzied schoolmaster has in mind? In order to distract his friend from the unpleasant interview with Jenny’s father and its even more unpleasant outcome, Wrayburn takes Mortimer for a stroll to show him how obstinately Bradley clings to his heels. It does not take long before the two really spot the teacher, and Eugene, of course, does not lose this opportunity to humiliate Bradley. All this is not suited to alloy the worries Mortimer feels with regard to the whole situation.

Tristram wrote: "Hello Friends,

Frankly speaking, this week’s reading assignment did not really come over as very enjoyable to me, mostly because there is little humour and a lot of sentimentality in the first two..."

Yes, Tristram. This chapter certainly reminds us that the Thames is, in itself, a character in the novel. I would say a major character at that. I agree with you as well that the chapter is one in which we can clearly see Dickens drawing the net of characters and circumstances closer together.

Betty, while a minor character, has a major role in forwarding the themes and focus of the novel. It was only a couple of weeks since we read about how Boffin worshipped at the alter of misers and relished all stories of how the rich could save money. Here, Betty offers the reader a far different perspective. Betty is proud, and, while she is poor, she carries a dignity that surpasses all the Veneerings and Boffin's and Fledgeby's of the novel. Her pride is based on the fact that she did work and that she did help others. Dickens calls her a "ruggedly honest creature" who wished to live and die "untouched by workhouse hands." She was, as Dickens writes, a "poor soul [who] envied no one in bitterness and grudged no one anything."

There are, as Tristram notes, two people Betty meets on her final pilgrimage. One is evil, a vulture, a person who we know already, a person who relishes death. The other is angelic, one who at one time also dealt with death, but now is angelic. It is here, in the presentation of these two different people as they meet with Betty, we see Dickens at his best.

I'll comment only on Lizzie, for in her I find Dickens at his symbolic best. First, let's go back to Book 1, Chapter 1 where we first meet Lizzie. Let's focus on how Dickens frames Lizzie here, and focus even more closely on her face and her frame of mind. We are told that "in the intensity of her look there was a touch of dread or horror." Lizzie "pulled the hood of a cloak she wore over her head and over her face." Her father at one point tells her to "take that thing off your face" to which Lizzie replies "No, no, father! No! ... I cannot sit so near it!" We know that this conversation revolves around a dead body. Lizzie's attempt to cover her face is an attempt to shut out the horror of death and the fact that this is how the Hexam family makes their money.

In this chapter we again meet Lizzie, and we again see how Dickens portrays her. Dickens again frames our experience with Lizzie through her face, but the differences are remarkable. When Betty awakens from her sleep "at the foot of the Cross" the darkness is gone "and a face is bending down." We read that this face is "of a woman, shaded by a quantity of rich dark hair." Betty thinks the face "must be an Angel." For the remainder of the chapter Dickens focuses on Lizzie's face which is now revealed. Lizzie comments "[y]ou can see my face here." (My italics) Lizzie constantly wets Betty's lips. Lizzie kisses Betty and Betty says "Bless ye! Now lift me, my love." And so Lizzie does lift the "weather-stained grey head ... as high as Heaven."

In this scene Dickens has taken Lizzie from a place on the Thames where she feared dead bodies and hid her face to a place where, again by the Thames, her face is totally revealed, and rather than being afraid of death, she is able to administer to Betty and, in a literal sense, even embrace death.

Dickens blends the concept of life and death with the presence of the Thames. He also clearly develops the character and nature of both Lizzie and Betty into characters of respect and admiration? And, of course, by implication, the Deputy Lock man, so concerned with Alfred Davids, still remains a haunting presence that proves that not all men are good, and not all men can change, regardless of their experiences with the Thames.

Frankly speaking, this week’s reading assignment did not really come over as very enjoyable to me, mostly because there is little humour and a lot of sentimentality in the first two..."

Yes, Tristram. This chapter certainly reminds us that the Thames is, in itself, a character in the novel. I would say a major character at that. I agree with you as well that the chapter is one in which we can clearly see Dickens drawing the net of characters and circumstances closer together.

Betty, while a minor character, has a major role in forwarding the themes and focus of the novel. It was only a couple of weeks since we read about how Boffin worshipped at the alter of misers and relished all stories of how the rich could save money. Here, Betty offers the reader a far different perspective. Betty is proud, and, while she is poor, she carries a dignity that surpasses all the Veneerings and Boffin's and Fledgeby's of the novel. Her pride is based on the fact that she did work and that she did help others. Dickens calls her a "ruggedly honest creature" who wished to live and die "untouched by workhouse hands." She was, as Dickens writes, a "poor soul [who] envied no one in bitterness and grudged no one anything."

There are, as Tristram notes, two people Betty meets on her final pilgrimage. One is evil, a vulture, a person who we know already, a person who relishes death. The other is angelic, one who at one time also dealt with death, but now is angelic. It is here, in the presentation of these two different people as they meet with Betty, we see Dickens at his best.

I'll comment only on Lizzie, for in her I find Dickens at his symbolic best. First, let's go back to Book 1, Chapter 1 where we first meet Lizzie. Let's focus on how Dickens frames Lizzie here, and focus even more closely on her face and her frame of mind. We are told that "in the intensity of her look there was a touch of dread or horror." Lizzie "pulled the hood of a cloak she wore over her head and over her face." Her father at one point tells her to "take that thing off your face" to which Lizzie replies "No, no, father! No! ... I cannot sit so near it!" We know that this conversation revolves around a dead body. Lizzie's attempt to cover her face is an attempt to shut out the horror of death and the fact that this is how the Hexam family makes their money.

In this chapter we again meet Lizzie, and we again see how Dickens portrays her. Dickens again frames our experience with Lizzie through her face, but the differences are remarkable. When Betty awakens from her sleep "at the foot of the Cross" the darkness is gone "and a face is bending down." We read that this face is "of a woman, shaded by a quantity of rich dark hair." Betty thinks the face "must be an Angel." For the remainder of the chapter Dickens focuses on Lizzie's face which is now revealed. Lizzie comments "[y]ou can see my face here." (My italics) Lizzie constantly wets Betty's lips. Lizzie kisses Betty and Betty says "Bless ye! Now lift me, my love." And so Lizzie does lift the "weather-stained grey head ... as high as Heaven."

In this scene Dickens has taken Lizzie from a place on the Thames where she feared dead bodies and hid her face to a place where, again by the Thames, her face is totally revealed, and rather than being afraid of death, she is able to administer to Betty and, in a literal sense, even embrace death.

Dickens blends the concept of life and death with the presence of the Thames. He also clearly develops the character and nature of both Lizzie and Betty into characters of respect and admiration? And, of course, by implication, the Deputy Lock man, so concerned with Alfred Davids, still remains a haunting presence that proves that not all men are good, and not all men can change, regardless of their experiences with the Thames.

Peter wrote: "Dickens has taken Lizzie from a place on the Thames where she feared dead bodies and hid her face to a place where, again by the Thames, her face is totally revealed, and rather than being afraid of death, she is able to administer to Betty and, in a literal sense, even embrace death.."

Peter wrote: "Dickens has taken Lizzie from a place on the Thames where she feared dead bodies and hid her face to a place where, again by the Thames, her face is totally revealed, and rather than being afraid of death, she is able to administer to Betty and, in a literal sense, even embrace death.."Excellent observations, Peter. I bow to those of you who make these connections that just pass me by. Brilliant.

Tristram wrote: "this week’s reading assignment did not really come over as very enjoyable to me, mostly because there is little humour and a lot of sentimentality ."

Tristram wrote: "this week’s reading assignment did not really come over as very enjoyable to me, mostly because there is little humour and a lot of sentimentality ."Despite its sentimentality, I was particularly moved by this chapter, and it all comes down to recognition. My parents moved into a retirement center at my mother's insistence. I don't know if they read the fine print or not, but my mom died and my dad reached a point where the institution didn't think he could live alone any longer. He HATED the assisted living unit, so opted to go back to an apartment on the condition that he have round-the-clock CNAs ("guards"). His last years were horrible because he could no longer live life on his own terms and be his own man. He would have gladly risked a broken hip or some private indignity to have his independence, but he'd signed away those rights. I thought of him as I read about Betty, and knew that he would be cheering her on, and would have happily died a pauper on a river bank rather than in the home that he considered a prison. :-(. Dickens may have been sentimental, but he was no fool.

Tristram wrote: "The following Chapter tells us how “Somebody Becomes the Subject of a Prediction”, and this Somebody is Bella Wilfer. Like the previous chapter, Chapter 9 is more a chapter of organization in that ..."

Tristram wrote: "The following Chapter tells us how “Somebody Becomes the Subject of a Prediction”, and this Somebody is Bella Wilfer. Like the previous chapter, Chapter 9 is more a chapter of organization in that ..."Bella always appears to take on the personality of those with whom she may currently be in contact...With Mrs. Lammle, she is a bit conniving and off putting, while honorable and kind with Lizzie. Bella is one of those characters who does not remain steadfast in my eyes, transforming and being drawn out by others. She may be young and impressionable, and spoiled, not having built strong character as of yet; regardless, I like watching her grow and change in these pages, coming into her own. It will be interesting to see who we will end up with, which Bella W. will endure.

Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out” ..."

Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out” ..."Much as I really loathe Eugene (and I've truly reached that point), I have to admit that I found his cat and mouse game with Headstone entertaining. I guess that just means I dislike Bradley even more - he deserves what he gets for being a stalker. Despite the perverse pleasure I derived from them traipsing around London in the middle of the night, it's still just more proof of what a jerk Eugene can be, as is the way he takes advantage of Jenny's father. Mortimer calls him out on it, but still remains his friend, which lowers him in my estimation, as well. Not that he cares what I think.

By the way, what do you make of Eugene’s habit of inventing names for other people?

Did anyone here used to watch "Lost"? (A show that was AMAZING in the first few seasons, but ended with a disappointing fizzle.) There was a character on that show (Sawyer) who had nicknames for everyone. Even though he was a bit prickly and the names were not always flattering, they still somehow seemed endearing coming from him. If you got a nickname, you were worthy of his notice type of thing. But Eugene doesn't seem to have that same twinkle in his eye. When he does it, it only seems derogatory and condescending, which is how I believe it's meant. These people are beneath him, and he doesn't feel the need to even go to the trouble of learning or using their real names. This chapter makes me wonder when someone is going to have enough of Eugene's particular charms, and finally pop him in the nose. Or worse.

Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out”, and Dickens would not not be Dickens if you could not understand the title of this chapter in at least two different ways. We are directly ..."

Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out”, and Dickens would not not be Dickens if you could not understand the title of this chapter in at least two different ways. We are directly ..."Habit of inventing people

Could this be more of Wrayburn's blatant disregard for people... Different names at different times for people of no matter to him in the big scheme of things?

In a previous thread, I asked the question why Wrayburn refers to Riah as "Aaron," Dickens being so deliberate with little aspects such as this. I think it may have gotten lost in the posts, but I went ahead and did a little research on my own. In Dickens Novels as Verse by Joseph P. Jordan, Jordan writes:

A couple of paragraphs after the repeated talk about the brother being the matter, Eugene calls Riah Aaron for the first time: If Mr. Aaron...will be good enough to relinquish his charge to me, he will be quite free for any engagement he may have at the Synagogue. In the Penguin edition, Adrian Poole glosses Aaron as the brother of Moses, first high priest of Israel, but for Wrayburn merely a way of demeaning Riah to stereotype (825). The name Aaron may be that for Wrayburn, but for readers it does a lot more. As Poole's note makes clear, Aaron is first and foremost a brother-Moses's brother. Aaron is also Moses's spokesman to the Israelites and to Pharaoh when the Israelites are slaves. Aaron a name thus associated with brother and slave, thus complexly echoes the talk about the brother being the matter (and, according to Eugene, being not worth a tear) from two paragraphs earlier-talk that in context refers to Lizzie's brother, Charley, but that continues the novel's intermittent tendency to allude, quietly, to the Anti-Slavery Society* and their motto (Am I not a man and a brother?). The remainder of Eugene's sentence solidifies the connection between the name Aaron and Am I not a man and a brother? He says that if Aaron...will be good enough to 'relinquish his charge' [Lizzie]-to give her up, to free her-Riah/Aaron will be quite 'free' for any engagement.

*We've discussed the effects of industrialization and the its revolution quite extensively as it pertains to Dickens's novels; however, we've never discussed an allusion to slavery, or this particular society in general. Here is a link to the BBC's website concerning British Anti-Slavery, and a wiki link for the Anti-Slavery Society.

Tristram wrote: " Kim, you are very lucky because you got those brilliant Wegg-Venus-Boffin encounters "

You are welcome to all the Wegg chapters you want. I don't like the guy at all.

You are welcome to all the Wegg chapters you want. I don't like the guy at all.

Ami wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out”, and Dickens would not not be Dickens if you could not understand the title of this chapter in at least two different ways...."

Ami

Thanks for opening up new places to explore and consider. There is so much breadth and depth to learn and come to terms with in this novel.

I found the links very informative.

Ami

Thanks for opening up new places to explore and consider. There is so much breadth and depth to learn and come to terms with in this novel.

I found the links very informative.

I wonder if late in his writing career, Dickens was pursuing a mystery writing career?

I wonder if late in his writing career, Dickens was pursuing a mystery writing career?There is certainly a mystery aspect in GE that is perhaps even stronger in OMF.

Not sure about the next one, not having read it yet, but the title sure makes a point.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out” ..."

Much as I really loathe Eugene (and I've truly reached that point), I have to admit that I found his cat and mouse ga..."

What you say about the nicknames with respect to Eugene, is exactly what I thought. He is just not interested in people and labels them with the help of external features. The same, and even worse, is true of him when he refrains from getting to know Bradley's name and only calls him by his profession.

Much as I really loathe Eugene (and I've truly reached that point), I have to admit that I found his cat and mouse ga..."

What you say about the nicknames with respect to Eugene, is exactly what I thought. He is just not interested in people and labels them with the help of external features. The same, and even worse, is true of him when he refrains from getting to know Bradley's name and only calls him by his profession.

John wrote: "I wonder if late in his writing career, Dickens was pursuing a mystery writing career?

There is certainly a mystery aspect in GE that is perhaps even stronger in OMF.

Not sure about the next one,..."

You are on to something there, considering that Dickens's final novel even has the word "Mystery" in its title. Maybe, he noticed that his friend Wilkie Collins was very successful as a mystery writer.

There is certainly a mystery aspect in GE that is perhaps even stronger in OMF.

Not sure about the next one,..."

You are on to something there, considering that Dickens's final novel even has the word "Mystery" in its title. Maybe, he noticed that his friend Wilkie Collins was very successful as a mystery writer.

Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "I wonder if late in his writing career, Dickens was pursuing a mystery writing career?

Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "I wonder if late in his writing career, Dickens was pursuing a mystery writing career?There is certainly a mystery aspect in GE that is perhaps even stronger in OMF.

Not sure about ..."

In my working days, I used to do some marketing. If I were to "market" Dickens in a different way, among the thousands and thousands of ways he has already been marketed, I would put together a boxed set of three called "The Dickens Mysteries."

And it would be GE, OMF, and Drood.

I might even subtitle it: "What the Dickens?"

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out”, and Dickens would not not be Dickens if you could not understand the title of this chapter in at least two dif..."

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The tenth Chapter informs us that there are “Scouts Out”, and Dickens would not not be Dickens if you could not understand the title of this chapter in at least two dif..."You're welcome, Peter. It really wasn't anything too important, just a little something. :)

John wrote: "Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "I wonder if late in his writing career, Dickens was pursuing a mystery writing career?

There is certainly a mystery aspect in GE that is perhaps even stronger in OMF...."

That's a nice idea!

There is certainly a mystery aspect in GE that is perhaps even stronger in OMF...."

That's a nice idea!

Both Tristram and Ami have commented on the use of multiple names for characters in the novel, or how one person will refer to another person, consciously or unconsciously, with more than one name. I think they are pointing out a very interesting and important aspect of the novel.

We know from long experience (and joy) how Dickens often blends a person's name with their personality. Could we then say that a person is a projection of their name? Of their nickname? Of their "pet" name?

Then I got to thinking ... Lizzie is a casual name for Elizabeth. Betty is a casual name for Elizabeth. Is Dickens, in some way, aligning Lizzie Hexam with Betty?

And then we have the fairy tale name associations. Riderhood and Ridinghood, Cinderella, fairy godmother to name a few that we have met so far.

And so it goes. I can think of no other novel of Dickens that seems to offer the reader so many different layers of names. Added to this is the fact that there are numerous incidences of people with secret lives and wild swings in personalities and we are faced with a dizzying array of possibilities. It is almost as if nothing is as it seems, and nothing can be accepted on face value or expected to remain constant.

We know from long experience (and joy) how Dickens often blends a person's name with their personality. Could we then say that a person is a projection of their name? Of their nickname? Of their "pet" name?

Then I got to thinking ... Lizzie is a casual name for Elizabeth. Betty is a casual name for Elizabeth. Is Dickens, in some way, aligning Lizzie Hexam with Betty?

And then we have the fairy tale name associations. Riderhood and Ridinghood, Cinderella, fairy godmother to name a few that we have met so far.

And so it goes. I can think of no other novel of Dickens that seems to offer the reader so many different layers of names. Added to this is the fact that there are numerous incidences of people with secret lives and wild swings in personalities and we are faced with a dizzying array of possibilities. It is almost as if nothing is as it seems, and nothing can be accepted on face value or expected to remain constant.

Peter wrote: "Both Tristram and Ami have commented on the use of multiple names for characters in the novel, or how one person will refer to another person, consciously or unconsciously, with more than one name...."

Peter wrote: "Both Tristram and Ami have commented on the use of multiple names for characters in the novel, or how one person will refer to another person, consciously or unconsciously, with more than one name...."Those are good thoughts, Peter. I had not thought of the Elizabeth/Lizzie/Betty alignment.

In the names, I found Riderhood too overt. It didn't work for me, and neither did Rokesmith -- which I found that there was nothing I could wrap my hands around that gave me a subtle connection or thought to what the character might be like. Perhaps therein lies the genius, though, when I thought about it more. It's like nothingness in a name and perhaps that was the idea.

The Flight

Book 3 Chapter 8

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

The setting is a market town on the upper reaches of the Thames, somewhere above Kingston, where the fiercely independent Betty Higden has been selling her wares. The moment realized is established by the following passage:

The poor old creature had taken the upward course of the river Thames as her general track; it was the track in which her last home lay, and of which she had last had local love and knowledge. She had hovered for a little while in the near neighbourhood of her abandoned dwelling, and had sold, and knitted and sold, and gone on. In the pleasant towns of Chertsey, Walton, Kingston, and Staines, her figure came to be quite well known for some short weeks, and then again passed on.

She would take her stand in market-places, where there were such things, on market days; at other times, in the busiest (that was seldom very busy) portion of the little quiet High Street; at still other times she would explore the outlying roads for great houses, and would ask leave at the Lodge to pass in with her basket, and would not often get it. But ladies in carriages would frequently make purchases from her trifling stock, and were usually pleased with her bright eyes and her hopeful speech. In these and her clean dress originated a fable that she was well to do in the world: one might say, for her station, rich. As making a comfortable provision for its subject which costs nobody anything, this class of fable has long been popular.

Nearing the end of her earthly pilgrimage at the upper reaches of the Thames, nearer its pure source and far removed from its polluted alterego in London, Betty is still terrified at the prospect of being ruled infirm and consigned by the parish authorities to the union workhouse. The enquiry by well-meaning but intrusive "Samaritans" usually begins by somebody's asking whether she has any relatives in the vicinity who will look after her:

'You have had a faint like,' was the answer, 'or a fit. It ain't that you've been a-struggling, mother, but you've been stiff and numbed.'

'Ah!' said Betty, recovering her memory. 'It's the numbness. Yes. It comes over me at times.'

Was it gone? the women asked her.

'It's gone now,' said Betty. 'I shall be stronger than I was afore. Many thanks to ye, my dears, and when you come to be as old as I am, may others do as much for you!'

They assisted her to rise, but she could not stand yet, and they supported her when she sat down again upon the bench.

'My head's a bit light, and my feet are a bit heavy,' said old Betty, leaning her face drowsily on the breast of the woman who had spoken before. 'They'll both come nat'ral in a minute. There's nothing more the matter.'

'Ask her,' said some farmers standing by, who had come out from their market-dinner, 'who belongs to her.'

'Are there any folks belonging to you, mother?' said the woman.

'Yes sure,' answered Betty. 'I heerd the gentleman say it, but I couldn't answer quick enough. There's plenty belonging to me. Don't ye fear for me, my dear.'

'But are any of 'em near here? 'said the men's voices; the women's voices chiming in when it was said, and prolonging the strain.

'Quite near enough,' said Betty, rousing herself. 'Don't ye be afeard for me, neighbours.'

'But you are not fit to travel. Where are you going?' was the next compassionate chorus she heard.

'I'm a-going to London when I've sold out all,' said Betty, rising with difficulty. 'I've right good friends in London. I want for nothing. I shall come to no harm. Thankye. Don't ye be afeard for me.'

A well-meaning bystander, yellow-legginged and purple-faced, said hoarsely over his red comforter, as she rose to her feet, that she 'oughtn't to be let to go'.

'For the Lord's love don't meddle with me!' cried old Betty, all her fears crowding on her. 'I am quite well now, and I must go this minute.'

She caught up her basket as she spoke and was making an unsteady rush away from them, when the same bystander checked her with his hand on her sleeve, and urged her to come with him and see the parish-doctor. Strengthening herself by the utmost exercise of her resolution, the poor trembling creature shook him off, almost fiercely, and took to flight. Nor did she feel safe until she had set a mile or two of by-road between herself and the marketplace. . . .

As Betty hastens away from the confrontation with the well-meaning crowd gathered in the village square before the Golden Lion Inn (identified by Stone as being behind the crowd), looking over her shoulder to assure herself that nobody is pursuing her. For an elderly woman who has just suffered a mild stroke, Betty moves with surprising speed despite her unsteady gait as she balances her large basket on her left arm and pushes her right arm determinedly forward. The perspective that Stone has chosen matches that of the text in that the viewer is situated in front of Betty, and therefore sees the townspeople somewhat indistinctly sketched in a hundred yards back, the illustration's focal character clearly being Betty, her expression denoting both apprehension and suspicion. Stone has framed the marketplace scene, placing the retreating Betty outside the societal frame, her gnarled, alienated state reiterated by the ancient, leafless tree on the other side of the stone fence (right).

"Lizzie Hexam very softly raised the weather-stained grey head, and lifted her as high as Heaven"

Book 3 Chapter 8

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"A look of thankfulness and triumph lights the worn old face. The eyes, which have been darkly fixed upon the sky, turn with meaning in them towards the compassionate face from which the tears are dropping, and a smile is on the aged lips as they ask: "What is your name, my dear?" "My name is Lizzie Hexam." "I must be sore disfigured. Are you afraid to kiss me?" The answer is, the ready pressure of her lips upon the cold but smiling mouth. "Bless ye! Now lift me, my love." Lizzie Hexam very softly raised the weather-stained grey head, and lifted her as high as Heaven."

Commentary:

Despite the fact that it was his visual antecedent, Marcus Stone's 1865 treatment of Betty Higden as the rebel, fleeing a town where the citizens seem to be contemplating sending her to the poorhouse, has little in common with James Mahoney's pathetic illustration of Betty's final moments in the woods near the paper-mill where Lizzie Hexam has fled to avoid Bradley Headstone's unwelcome attention. Whereas the Irish artist probably first read this part of the novel and encountered Stone's wood-engraving The Flight in the May 1865 installment, not in the context of the June 1865 issue of Henry Harper's new vehicle for publishing fiction, Harper's New Monthly Magazine, in which illustrators Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sol Eytinge, Jr., the first American illustrators of Our Mutual Friend must have initially read the novel. American readers such as these two illustrators would have encountered the sentimental death of Betty Higden, attended by Lizzie Hexam, near the paper-mill on the upper Thames in Part 13 (June 1865), pages 101-121 in Harper's, an installment that includes Bibliomania of the Golden Dustman, The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin (both relating to the previous number, published in the New York periodical in May), and the two wood-engravings pertaining to the June installment, The Flight, and Threepenn'orth Rum, the former two appearing in Great Britain in the April 1865 number and the latter two in the May 1865 installment. Mahoney, impressed by the death of Betty Higden, which comes at the very end of Chapter 8 in the third book, must have felt that this sentimental moment was worthier of visual comment than Betty's hurrying out of the Thames town, fearful that, having lived outside the state welfare system her whole life, was about to be committed to the custody of the local Guardians of the Poor Law and suffer the indignity of a pauper's grave, if not of having her corpse sold to an anatomist.

As Ruth Richardson notes, over the course of thirty years, beginning with Oliver Twist, Dickens had presented a uniform assault on the institution of the workhouse and the act of Parliament that created it, the 1834 Poor Law, utilizing editorials in Household Words as well as fictional characters:

Among the most recent of these had been the character of Betty Higden in Our Mutual Friend, who takes to the road rather than die in a workhouse. The book was the last novel Dickens completed before his death, published in parts over the period of 1864-5 — just ahead of and in parallel with the Lancet Sanitary Commission's Reports. The words the audience at the great meeting heard [Dr. Joseph] Rogers read aloud referring to the poor creeping into corners to die rather than fester and rot in workhouse wards, refer to those — young and old — who preferred to sleep out under the stars rather than enter those hateful places, and to the incomprehension which met their deaths. Dickens's creation Betty Higden addresses this incomprehension, by way of explaining the self-respect that refused to be browbeaten by the coercive humiliation of applying for help to the workhouse. [Richardson 296]

The novel, then, appeared a year before the government's official enquiry into the continuing abuses of the workhouse system vindicated Dickens's attack most pointedly delivered in the death of Betty Higden. Through her fictional sufferings, Betty helped to bring down the workhouses, which progressive parliamentarians replaced with a system of public infirmaries for the poor who were ill, and instituted the Metropolitan Asylums Board for those indigents who were insane or had infectious diseases. The new hospitals constructed in the decade following Our Mutual Friend became the basis for the National Health Service.

In contrast to the simplicity of Eytinge's wood-engraving, Mahoney's wood-engraving like Darley's frontispiece presents Betty in a natural, detailed setting. Whereas Darley intensifies her humanity in her final moments through her look of dazed confusion at the young woman whom she mistakes for an angel, Betty is old and gnarled in Stone's and Mahoney's final illustrations of her, but is very near death in the Household Edition. In Stone, she marches determinedly away from town with the talk of the poorhouse, but in Mahoney she is tended like a child by Lizzie Hexam as her apparently lifeless hand lies beside her basket of knitting. In the background, Mahoney supplies a weir, mill-wheel, and a lighted factory building, but emphasizes the vegetation, perhaps with the implication that her death before such a building is more natural than in a workhouse. In particular, Mahoney gives prominence to the leafless tree under which Betty has taken refuge. Through it the illustrator may well be implying that Betty has striven for and achieved a death in nature, retaining her dignity and individuality to the end. In the 1875 plate, Lizzie seems relatively anonymous, whereas in the Darley frontispiece she is well dressed, her hair neatly arranged, like the mill-girls of Lowell, Massachusetts, and Manchester, New Hampshire.

"The end of a long Journey"

Book 3 Chapter 8

Felix O. C. Darley

1866

Text Illustrated:

She crept among the trees to the trunk of a tree whence she could see, beyond some intervening trees and branches, the lighted windows, both in their reality and their reflection in the water. She placed her orderly little basket at her side, and sank upon the ground, supporting herself against the tree. It brought to her mind the foot of the Cross, and she committed herself to Him who died upon it. Her strength held out to enable her to arrange the letter in her breast, so as that it could be seen that she had a paper there. It had held out for this, and it departed when this was done.

"I am safe here," was her last benumbed thought. "When I am found dead at the foot of the Cross, it will be by some of my own sort; some of the working people who work among the lights yonder. I cannot see the lighted windows now, but they are there. I am thankful for all!"

The darkness gone, and a face bending down.

"It cannot be the boofer lady?"

"I don't understand what you say. Let me wet your lips again with this brandy. I have been away to fetch it. Did you think that I was long gone?"

It is as the face of a woman, shaded by a quantity of rich dark hair. It is the earnest face of a woman who is young and handsome. But all is over with me on earth, and this must be an Angel.

"Have I been long dead?"

"I don't understand what you say. Let me wet your lips again. I hurried all I could, and brought no one back with me, lest you should die of the shock of strangers."

"Am I not dead?"

Commentary:

It is quite likely that both Darley and Sol Eytinge, Jr., the first American illustrators of Our Mutual Friend first read the novel as a monthly serial in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864 through December 1865 — in other words, in installments that were exactly one month later than the monthly parts issued in Great Britain (May 1864 through November 1865). American readers such as these two illustrators would have encountered the sentimental death of Betty Higden, attended by Lizzie Hexam, near the paper-mill on the upper Thames in Part 13 (June 1865), pages 101-121 in Harper's, an installment that includes Bibliomania of the Golden Dustman, The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin (both relating to the previous number, published in the New York periodical in May), and the two wood-engravings pertaining to the June installment, The Flight, and Threepenn'orth Rum, the former two appearing in Great Britain in the April 1865 number and the latter two in the May 1865 installment.

Thus, the thirteenth installment, which would have contained the twelfth chapter of the third book, Darley would probably have read in June 1865, less than twelve months ahead of when he executed the four frontispieces for the Hurd and Houghton "Household Edition" initiated five years earlier by New York publisher James G. Gregory. Undoubtedly the dramatic death of Betty would have had a powerful effect on both American illustrators, but only Darley's program permitted him to realize the sentimental scene in which Betty Higden dies of a stroke in the woods rather than take refuge in the universally detested union workhouse. In fact, to forestall some well-meaning attempt to carry her corpse to such a place for burial, Betty has sewn the money to cover the cost of a decent burial into the lining of her skirt.

In contrast to the simplicity of Eytinge's wood-engraving, Darley's frontispiece presents Betty in a natural, detailed setting. She is old and gnarled in Stone's and Mahoney's final illustrations of her, but Darley intensifies her humanity in her final moments through her look of dazed confusion at the young woman whom she mistakes for an angel. In Stone, she marches determinedly away from town with the talk of the poorhouse, but in Darley she tries to sit up against the tree at whose base she has fallen. Whereas Mahoney in Lizzie Hexam very softly raised the weather-stained grey head, and lifted her as high as Heaven supplies a weir, mill-wheel, and factory as the backdrop (perhaps with the implication that her death before such a building is more fitting than in a workhouse), Darley minimizes both the dwelling (right rear) and the mill-wheel and factory (left rear) to focus on Betty and her nurse, surrounded by her bonnet, basket, and knitting by which she has been making a meagre living these past weeks. The leafless tree in the Mahoney plate may well be a Betty has striven for and achieved a "natural" death, retaining her dignity and individuality to the end. Lizzie seems relatively anonymous in the Mahoney illustration, but Darley presents her as well dressed, her hair neatly arranged, like the mill-girls of Lowell, Massachusetts, and Manchester, New Hampshire.

The American illustrators would have been well ware of the short-comings of the poorhouse as a vehicle for the relief of the old and indigent, but the Civil War, just concluded when Darley executed this frontispiece, meant that relatively few people actually went to the poorhouse because federal legislation sought to alleviate the sufferings of families who had lost sons and fathers as breadwinners during the conflict. In the next decade, reforms similar to those of Great Britain effectively outlawed the placing of children, the aged, infirm, and sick in poorhouses. But the unsavory reputation of the American poorhouse prior to the 1860s would certainly have affected Darley's interpretation of Betty's determination to die outside such an institution. Certainly one can better appreciate Fanny Robin's pathetic death in Thomas Hardy's Far from the Madding Crowd (September 1874 installment) if one has already encountered Betty Higden's dying under an oak tree; Hardy's illustrator, Helen Paterson Allingham, elected to show a desperate young woman, pregnant and friendliness, sleeping outside in She opened a gate within which was a haystack rather than dying inside the Casterbridge Union Workhouse, which appears as a shadowy presence in the initial-letter vignette for that number.

"So they walked, speaking of the newly filled-up grave, and of Johnny, and of many things"

Book 3 Chapter 9

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

As they spoke they were leaving the little street and emerging on the wooded landscape by the river.

"You think well of her, Mr. Rokesmith?" pursued Bella, conscious of making all the advances.

"I think highly of her."

"I am so glad of that! Something quite refined in her beauty, is there not?"

"Her appearance is very striking."

"There is a shade of sadness upon her that is quite touching. At least I — I am not setting up my own poor opinion, you know, Mr. Rokesmith," said Bella, excusing and explaining herself in a pretty shy way; "I am consulting you."

"I noticed that sadness. I hope it may not," said the Secretary in a lower voice, "be the result of the false accusation which has been retracted."

When they had passed on a little further without speaking, Bella, after stealing a glance or two at the Secretary, suddenly said:

"Oh, Mr. Rokesmith, don't be hard with me, don't be stern with me; be magnanimous! I want to talk with you on equal terms."

The Secretary as suddenly brightened, and returned: "Upon my honour I had no thought but for you. I forced myself to be constrained, lest you might misinterpret my being more natural. There. It's gone."

"Thank you," said Bella, holding out her little hand. "Forgive me."

Bella met the steady look for a moment with a wistful, musing little look of her own, and then, nodding her pretty head several times, like a dimpled philosopher (of the very best school) who was moralizing on Life, heaved a little sigh, and gave up things in general for a bad job, as she had previously been inclined to give up herself.

But, for all that, they had a very pleasant walk. The trees were bare of leaves, and the river was bare of water-lilies; but the sky was not bare of its beautiful blue, and the water reflected it, and a delicious wind ran with the stream, touching the surface crisply. Perhaps the old mirror was never yet made by human hands, which, if all the images it has in its time reflected could pass across its surface again, would fail to reveal some scene of horror or distress. But the great serene mirror of the river seemed as if it might have reproduced all it had ever reflected between those placid banks, and brought nothing to the light save what was peaceful, pastoral, and blooming.

So, they walked, speaking of the newly filled-up grave, and of Johnny, and of many things. So, on their return, they met brisk Mrs. Milvey coming to seek them, with the agreeable intelligence that there was no fear for the village children, there being a Christian school in the village, and no worse Judaical interference with it than to plant its garden. So, they got back to the village as Lizzie Hexam was coming from the paper-mill, and Bella detached herself to speak with her in her own home.

Commentary:

The Harper and Brothers woodcut for ninth chapter, "Somebody becomes the Subject of a Prediction," in the third book, "A Long Lane," has a very different caption than that in the Chapman and Hall volume, published that same year in London: "Oh, Mr. Rokesmith, don't be hard with me, don't be stern with me" — although the reference in each case is to a conversation between John Rokesmith as Boffin's secretary and the adopted Bella Wilfer, the quotations employed as captions affect the reception of the illustration. The American edition suggests a romantic and perhaps even flirtatious undertone to the conversation (an implication not reinforced by a reading of the text itself), whereas the British edition implies that weightier subjects are under discussion: "So, they walked, speaking of the newly filled-up grave, and of Johnny, and of many things". This is yet another of those illustrations possessing a different caption in the Chapman and Hall and Harper and Brothers versions of the same book, suggesting that, although the American publisher must have received a list of illustrations, but chose occasionally to deviate from the given wording, although the American edition contains no "List of Illustrations." Two further examples are Witnessing the Agreement and Mr. and Mrs. Lammle, both of which have much longer captions in the London text.

Despite the fact that it was his visual antecedent, the original edition illustrated by Marcus Stone in 1865 has several illustrations involving Bella Wilfer and the Boffins' secretary, John Rokesmith (in reality, John Harmon), this particular series of chapters in the third book does not contain an illustration involving the pair.

In the original thirteenth installment (May 1865), Betty Higden dies in Lizzie Hexam's arms, and then the Reverend Frank Milvey and his wife arrive in company with the Boffins' Secretary and Bella Wilfer, who have brought the replacement adopted orphan, Sloppy, with them to attend Betty's funeral. Lizzie, who has taken a job at a paper mill on the upper Thames to escape both Eugene Wrayburn and Bradley Headstone, has impressed Bella with her depth of feeling in unburdening herself about her melancholy history. In fact, her appreciation of Lizzie's situation has fundamentally changed her attitude towards life, Bella confides to Rokesmith. Instead of setting the scene in the mill town or with the Plashwater Weir as a backdrop, Mahoney provides continuity with the scene in which Betty died by emphasizing the leafless trees that recall the mournful setting of that illustration, and contribute to a somber mood, which the downward glances of the couple in dark clothing reinforce.

John and Bella appear with other characters in the 1867 Diamond Edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr., the second among American illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, but not together, and do not appear in the Sheldon and Company (New York) Household Edition's 1866 frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and John Gilbert.

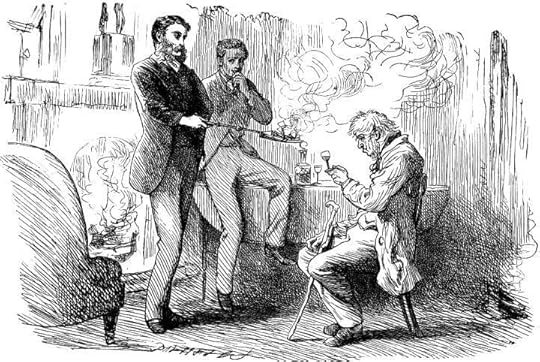

Three-Penn'orth Rum

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

The setting is once again, as in "Forming the Domestic Virtues" (November 1864), the bachelor apartments of Mortimer Lightwood (right) and Eugene Wrayburn (left) in the Temple. Indeed, by his positioning of the young attorneys and configuration of the room, Stone appears to have been inviting the serial reader to compare the earlier scene, in which Charley Hexam and Bradley Headstone confronted Eugene about the lawyer's interest in Lizzie, with the present scene, in which Eugene is interrogating "Mr. Dolls" (Jenny Wren's alcoholic father) about Lizzie's whereabouts. The moment realized occurs at the conclusion of the following passage, after Eugene has attempted to fumigate the disreputable, odorous inebriate by burning pastilles on the coal shovel:

What do you want?'

Mr. Dolls collapsed in his chair, and faintly said 'Threepenn'orth Rum.'

'Will you do me the favour, my dear Mortimer, to wind up Mr. Dolls again?' said Eugene. 'I am occupied with the fumigation.'

A similar quantity was poured into his glass, and he got it to his lips by similar circuitous ways. Having drunk it, Mr. Dolls, with an evident fear of running down again unless he made haste, proceeded to business.

'Mist Wrayburn. Tried to nudge you, but you wouldn't. You want that drection. You want t'know where she lives. Do you, Mist Wrayburn?'

With a glance at his friend, Eugene replied to the question sternly, 'I do.'

'I am er man,' said Mr. Dolls, trying to smite himself on the breast, but bringing his hand to bear upon the vicinity of his eye, 'er do it. I am er man er do it.'

'What are you the man to do?' demanded Eugene, still sternly.

'Er give up that drection.'

'Have you got it?'

With a most laborious attempt at pride and dignity, Mr. Dolls rolled his head for some time, awakening the highest expectations, and then answered, as if it were the happiest point that could possibly be expected of him: 'No.'

'What do you mean then?'

Mr. Dolls, collapsing in the drowsiest manner after his late intellectual triumph, replied: 'Threepenn'orth Rum.'

'Wind him up again, my dear Mortimer,' said Wrayburn; 'wind him up again.'

'Eugene, Eugene,' urged Lightwood in a low voice, as he complied, 'can you stoop to the use of such an instrument as this?'

'I said,' was the reply, made with that former gleam of determination, 'that I would find her out by any means, fair or foul. These are foul, and I'll take them — if I am not first tempted to break the head of Mr. Dolls with the fumigator. Can you get the direction? Do you mean that? Speak! If that's what you have come for, say how much you want.'

'Ten shillings — Threepenn'orths Rum,' said Mr. Dolls.

'You shall have it.'

As Eugene and Mortimer focus on their guest, he focuses exclusively on the wineglass in Stone's illustration. Stone is less specific about the room's furnishings than in the previous scene set in this room, and does not even indicate the location of the window, but retains the chair (down left) and the fireplace in the same approximate positions for the sake of continuity. The three figures are disposed in a triangle with Eugene at the apex, apparently in charge but actually being manipulated by the inferior drunkard. The source of suspense, which is fostered by the illustration, is whether in fact Jenny's dissolute father has any real information with which to leverage a few drinks and a lump sum payment, and subsequently whether therefore Eugene will be able to deploy so vile an "instrument" in pursuit of the object of his affections. The question then is really, "Who is using whom?" Mr. Dolls restrains himself, playing the young attorney, determined to abstract as much liquor and small change as possible. And, as Eugene afterwards confesses to his friend, if he is to find Lizzie he "can't do without him." As is so often the case in this novel, one character hopes to convert knowledge or information into money, or, more properly, what money can buy.

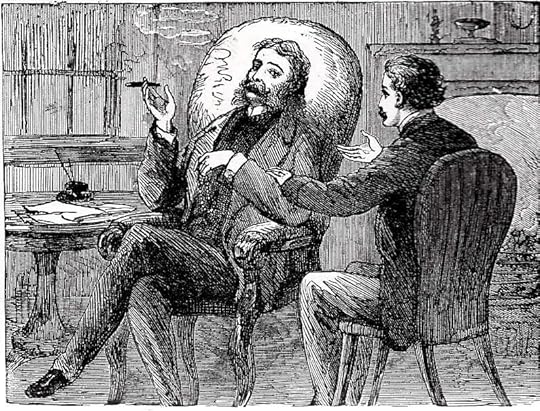

"Wrayburn and Lightwood"

Book 3 Chapter 10

Sol Eytinge Jr.

1870

Commentary:

Mortimer Lightwood, solicitor, takes an avuncular interest in his friend and colleague, the younger barrister Eugene Wrayburn, even though the latter has barely had a case since being called to the bar. Here the two, meeting at their club, discuss Eugene's romantic interest in Gaffer Hexam's daughter, Lizzie. Eytinge, who imagines the older attorney as mustachioed and larger in frame than the younger, establishes Lightwood as a kind of father-confessor to his younger protégé by their juxtapositions and gestures . In fact, the two are much closer in age than Eytinge implies in this illustration. Lightwood's sole business is his administration of the Harmon inheritance; hence, his fascination with John Harmon's murder, a topic which he discussed at some length at the opening of the novel, at the Veneerings' dinner. Although Eytinge depicts Lightwood as the more fashionably dressed, Wrayburn is in fact a dandy. The pair of lawyers conspire to bribe "Mr. Dolls," Jenny Wren's alcoholic father, in order to ascertain Lizzie's whereabouts. Already the indolent attorney, a reiteration perhaps of Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities (1859), seems animated by his interest in something or somebody other than himself.

Eytinge illustrated the following passage set in the attorneys' chambers in Book Three, "A Long Lane," chapter 10, "Scouts Out":

Lightwood was at home when he got to the Chambers, and had dined alone there. Eugene drew a chair to the fire by which he was having his wine and reading the evening paper, and brought a glass, and filled it for good fellowship's sake.

'My dear Mortimer, you are the express picture of contented industry, reposing (on credit) after the virtuous labours of the day.'

'My dear Eugene, you are the express picture of discontented idleness not reposing at all. Where have you been?'

'I have been,' replied Wrayburn, 'about town, I have turned up at the present juncture, with the intention of consulting my intelligent and respected solicitor on the position of my affairs.'

'Your highly intelligent and respected solicitor is of opinion that your affairs are in a bad way, Eugene.'

'Though whether,' said Eugene thoughtfully, 'that can be intelligently said, now, of the affairs of a client who has nothing to lose and who cannot possibly be made to pay, may be open to question.'

'You have fallen into the hands of the Jews, Eugene.'

'My dear boy,' returned the debtor, very composedly taking up his glass, 'having previously fallen into the hands of some of the Christians, I can bear it with philosophy.'

'I have had an interview to-day,Eugene, with a Jew, who seems determined to press us hard. Quite a Shylock, and quite a Patriarch. A picturesque grey-headed and grey-bearded old Jew, in a shovel-hat and gaberdine.'

'Not,' said Eugene, pausing in setting down his glass, 'surely not my worthy friend Mr. Aaron?'

'. . . I hope it may not be my worthy friend Mr. Aron, for, to tell you the truth, Mortimer, I doubt he may have a pre-possession against me. I strongly suspect him of having had a hand in spiriting away Lizzie.'

'Everything,' returned Lightwood impatiently, 'seems, by a fatality, to bring us round to Lizzie. "About town" meant about Lizzie, just now, Eugene.'

'My solicitor, do you know,' observed Eugene, turning round to the furniture, 'is a man of infinite discernment.'

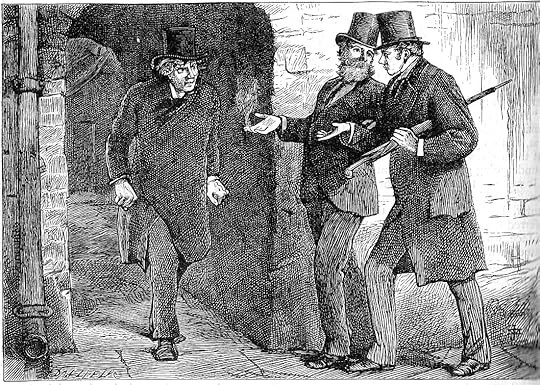

"They almost ran against Bradley Headstone"

Book 3 Chapter 10

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

At last, far on in the third hour of the pleasures of the chase, when he had brought the poor dogging wretch round again into the City, [Eugene] twisted Mortimer up a few dark entries, twisted him into a little square court, twisted him sharp round again, and they almost ran against Bradley Headstone.

"And you see, as I was saying, Mortimer," remarked Eugene aloud with the utmostcoolness, as though there were no one within hearing by themselves: "and you see, as I was saying — undergoing grinding torments."

It was not too strong a phrase for the occasion. Looking like the hunted and not the hunter, baffled, worn, with the exhaustion of deferred hope and consuming hate and anger in his face, white-lipped, wild-eyed, draggle-haired, seamed with jealousy and anger, and torturing himself with the conviction that he showed it all and they exulted in it, he went by them in the dark, like a haggard head suspended in the air: so completely did the force of his expression cancel his figure.

Mortimer Lightwood was not an extraordinarily impressible man, but this face impressed him.

Commentary:

Despite the fact that it was his visual antecedent, the original edition illustrated by Marcus Stone for the May 1865 number has a picture of "Mr. Dolls," Jenny Wren's father, disgustingly drunk and cadging three pennyworths of rum from the attorneys' in Three-Penn'orth Rum, which also offers Stone's interpretation of Mortimer Lightwood (left) and Eugene Wrayburn (right) in their rooms in The Inner Temple, as in Forming the Domestic Virtues (November 1864). Although Mahoney took Stone's lawyers as his models, he seems to have dissatisfied with Stone's version of Bradley Headstone, whom he supplies in the present illustration with a much more malevolent look, giving the reader a clearer image of the schoolmaster's face than in the Stone sequence. Here, Headstone has been led a merry chase by Wrayburn, who is well aware that the jealous schoolmaster has been following him.

Bradley Headstone, a bundle of nerves, appears paired with his self-centered acolyte, Charlie Hexam, in the 1867 Diamond Edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr., the second among American illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, but this version of the villainous Headstone seems far more deranged and volatile then Stone's. Eytinge also provides a convincing portrait of the lawyers, Wrayburn and Lightwood — the figure of Lightwood with muttonchops clearly based on the lawyer in the Stone original. Unfortunately, neither Felix Octavius Carr Darley nor John Gilbert offered studies of any of these characters in the Sheldon and Company (New York) Household Edition's 1866 four frontispieces for the novel.

Peter wrote: "Then I got to thinking ... Lizzie is a casual name for Elizabeth. Betty is a casual name for Elizabeth. Is Dickens, in some way, aligning Lizzie Hexam with Betty?"

Good hint, Peter! It never occurred to me before and shows, once again, how reading Dickens's novel in our group is an invaluable experience to me.

Good hint, Peter! It never occurred to me before and shows, once again, how reading Dickens's novel in our group is an invaluable experience to me.

Kim wrote: "The Flight

Book 3 Chapter 8

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

The setting is a market town on the upper reaches of the Thames, somewhere above Kingston, where the fiercely independent Betty Higden has b..."

Oh my, Kim. So many illustrations you have given us this week. Thank you. I find each week something in the text that I have missed, and the commentary and especially the illustrations, makes everything more clear.

For example, in this illustration of Betty the accompanying text says "with her bright eyes and hopeful speech. In these and her clean dress originated the fable that she was well to do in the world: one might say, for her station, rich."