The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 4, Chp. 1 - 4

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

The title of the second chapter promises us that “The Golden Dustman Rises a Little“, and I don’t know about you, but I was surely happy to hear that. The scene is Mr Boffin’s house, and our friend has guests – the wonderful Lammles:

As we know how fond those two are of each other, this does not bode too well for our friends, the Boffins. The Lammles are performing their usual show of loving husband and wife in order to make a good impression on their victims, and their base and shallow flatteries of each other and their hosts was getting so much on my nerves that I was happy to find Mr Boffin putting a stop to it when they alluded to Mr Rokesmith and Bella:

It’s nice to see that for all his changes Mr Boffin has not yet lost his concerns with his wife’s well-being and his respect for her. This acuteness also offers a beneficial contrast to the paltry protestations of affection for each other we get from Mr and Mrs Lammle. Mr Boffin’s language may not be as refined and flowery, but it smells better. Without much ado, Mr Boffin then says that the Lammles have done him and service and that he wishes to remunerate them. He then offers them an envelope containing a hundred pounds. This bluntness, and the fact that the envelope, strictly speaking, not only contains 100 Pounds but also an insult (although Mr Boffin clearly does not want to insult the Lammles), cools off the Lammles’ expectations. Mr Boffin then goes on by saying that he neither wishes Mr Lammle to take Mr Rokesmith’s position nor Mrs Lammle to become a confidante to Mrs Boffin. Again, Mr Boffin’s manner is open and direct but also characterized by the absence of spite or insolence.

Alfred and Sophronia react as we might have expected them to react: Mr Lammle’s face shows white spots as signs of his badly-repressed anger, and Mrs Lammle shows a more brazen behaviour by laughing impudently and making snide remarks. All of a sudden, however, Georgiana Podsnap rushes into the room, completely in tears. She apologizes to the Boffins for barging in like that but, as she says, she has heard that her only friend, Sophronia, has lost everything and this visit at the Boffins’ is her only chance to meet her once more because her parents have forbidden her any form of intercourse with the Lammles. Georgiana offers the Lammles a sum of 15 Pounds in cash – the only money she has got – and a necklace so that they have something to start a new life with. Mr Boffin takes care of securing the money and the jewels, but I think that Sophronia at least would not have taken them, anyway, because the affection and the love of the naïve young woman have touched her heart:

Seeing this state of affairs, and not being of a self-righteous nature, Mr Boffin does not undeceive the young girl as to Mrs Lammle’s true character but promises her to see to it that the necklace will be put to good use for the Lammles. While her husband is disappointed that he will neither touch the money nor the necklace, Mrs. Lammle shows herself very thankful to Mr Boffin for having spared her a humiliation and the poor girl an experience of disillusionment – which Mr Lammle counters by confounding his wife for being sentimental.

That tormented woman then exclaims:

With these words, the Lammles walk out of the Boffins’ house – and I wonder whether they have also walked out of the story?

”They were in a charming state of mind, were Mr and Mrs Lammle, and almost as fond of Mr and Mrs Boffin as of one another.”

As we know how fond those two are of each other, this does not bode too well for our friends, the Boffins. The Lammles are performing their usual show of loving husband and wife in order to make a good impression on their victims, and their base and shallow flatteries of each other and their hosts was getting so much on my nerves that I was happy to find Mr Boffin putting a stop to it when they alluded to Mr Rokesmith and Bella:

”’[…] It’s not above-board and it’s not fair. When the old lady is uncomfortable, there’s sure to be good reason for it. […]’”

It’s nice to see that for all his changes Mr Boffin has not yet lost his concerns with his wife’s well-being and his respect for her. This acuteness also offers a beneficial contrast to the paltry protestations of affection for each other we get from Mr and Mrs Lammle. Mr Boffin’s language may not be as refined and flowery, but it smells better. Without much ado, Mr Boffin then says that the Lammles have done him and service and that he wishes to remunerate them. He then offers them an envelope containing a hundred pounds. This bluntness, and the fact that the envelope, strictly speaking, not only contains 100 Pounds but also an insult (although Mr Boffin clearly does not want to insult the Lammles), cools off the Lammles’ expectations. Mr Boffin then goes on by saying that he neither wishes Mr Lammle to take Mr Rokesmith’s position nor Mrs Lammle to become a confidante to Mrs Boffin. Again, Mr Boffin’s manner is open and direct but also characterized by the absence of spite or insolence.

Alfred and Sophronia react as we might have expected them to react: Mr Lammle’s face shows white spots as signs of his badly-repressed anger, and Mrs Lammle shows a more brazen behaviour by laughing impudently and making snide remarks. All of a sudden, however, Georgiana Podsnap rushes into the room, completely in tears. She apologizes to the Boffins for barging in like that but, as she says, she has heard that her only friend, Sophronia, has lost everything and this visit at the Boffins’ is her only chance to meet her once more because her parents have forbidden her any form of intercourse with the Lammles. Georgiana offers the Lammles a sum of 15 Pounds in cash – the only money she has got – and a necklace so that they have something to start a new life with. Mr Boffin takes care of securing the money and the jewels, but I think that Sophronia at least would not have taken them, anyway, because the affection and the love of the naïve young woman have touched her heart:

”There were actually tears in the bold woman’s eyes, as the soft-headed and soft-hearted girl twined her arms about her neck.”

Seeing this state of affairs, and not being of a self-righteous nature, Mr Boffin does not undeceive the young girl as to Mrs Lammle’s true character but promises her to see to it that the necklace will be put to good use for the Lammles. While her husband is disappointed that he will neither touch the money nor the necklace, Mrs. Lammle shows herself very thankful to Mr Boffin for having spared her a humiliation and the poor girl an experience of disillusionment – which Mr Lammle counters by confounding his wife for being sentimental.

That tormented woman then exclaims:

”‘You have had no former cause of complaint on the sentimental score, Alfred, and you will have none in future. It is not worth your noticing. We go abroad soon, with the money we have earned here?’

‘You know we do; you know we must.’

‘There is no fear of my taking any sentiment with me. I should soon be eased of it, if I did. But it will be all left behind. It is all left behind. Are you ready, Alfred?’”

With these words, the Lammles walk out of the Boffins’ house – and I wonder whether they have also walked out of the story?

The preceding chapter has shown us how one potential danger – Mr Boffin in the claws and clutches of the Lammles – has been averted, but Chapter 3 has us witness how “The Golden Dustman Sinks Again”. It is the evening of the same day that Mr Boffin has shown himself in a better light, and our Golden Dustman is directing his steps to the Bower, its being a reading night, when he meets Mr Venus by appointment on his way. Venus informs him that this is probably going to be the night when Mr Wegg is finally laying his cards on the table, information that upsets Mr Boffin a lot.

When they arrive at the power, Mr Boffin notices a change in Mr Wegg’s manner in that there is no longer any deference in the literary man’s bearing. After a short, and ironic, introduction, Mr Wegg has it out with his patron and master, first by saying that for brevity’s sake he will no longer call him Mr Boffin but simply Boffin, and then by saying that he is no longer going to read anything to him:

Mr Boffin meekly submits to Wegg’s demands, and even the third stipulation, namely that henceforth Wegg shall be considered master of the premises and that Sloppy is to be sent away immediately, does not meet with any resistance on the part of the crest-fallen Mr Boffin. Wegg then informs Boffin that the whole property is to be divided into three parts and that he has to hand over two of these thirds to Wegg and Venus and to make amends for the part of the property he has already spent. He will also be charged with 1,000 Pounds for the bottle he took with him that night. Mr Boffin makes some remonstrances when he notices how much he has to hand over to Wegg, claiming that he is going to be ruined, but Wegg’s threat to go and publish the later will soon brings Mr Boffin round to accepting the demands made on him. Interestingly, he asks Wegg not to impart any knowledge of the new situation to his wife, who – Mr Boffin says – has grown quite used to their new station in life and would be worried if she knew it stood in danger.

What is Mr Boffin’s motive for saying this? Is it himself or his wife who clings more to their worldly possessions? Does he really want to spare her any worries, or is he afraid she might not want to have anything to do with this blackmail affair and prevail on Boffin to renounce the whole property altogether?

Mr Wegg generously makes this concession to spare Mrs Boffin’s feelings. They have meanwhile gone to Venus’s shop in order to let Mr Boffin have a look at the will that threatens his claim to the Harmon property. I noticed that by now Mr Boffin must have picked up some reading skills because he is able to read the will on his own – even though he does it very slowly and with effort. After Boffin has satisfied (or dissatisfied) himself as to the existence of the will, he is taken home by Mr Wegg, who repeatedly makes him sense his new power by calling him back through the keyhole of his front door.

Before I forget, the last of Mr Wegg’s demands – namely that Rokesmith be dismissed – does not seem to depress Mr Boffin very much.

When they arrive at the power, Mr Boffin notices a change in Mr Wegg’s manner in that there is no longer any deference in the literary man’s bearing. After a short, and ironic, introduction, Mr Wegg has it out with his patron and master, first by saying that for brevity’s sake he will no longer call him Mr Boffin but simply Boffin, and then by saying that he is no longer going to read anything to him:

”’[…] I’ve been your slave long enough. I’m not to be trampled under-foot by a dustman any more. With the single exception of the salary, I renounce the whole and total sitiwation.’”

Mr Boffin meekly submits to Wegg’s demands, and even the third stipulation, namely that henceforth Wegg shall be considered master of the premises and that Sloppy is to be sent away immediately, does not meet with any resistance on the part of the crest-fallen Mr Boffin. Wegg then informs Boffin that the whole property is to be divided into three parts and that he has to hand over two of these thirds to Wegg and Venus and to make amends for the part of the property he has already spent. He will also be charged with 1,000 Pounds for the bottle he took with him that night. Mr Boffin makes some remonstrances when he notices how much he has to hand over to Wegg, claiming that he is going to be ruined, but Wegg’s threat to go and publish the later will soon brings Mr Boffin round to accepting the demands made on him. Interestingly, he asks Wegg not to impart any knowledge of the new situation to his wife, who – Mr Boffin says – has grown quite used to their new station in life and would be worried if she knew it stood in danger.

What is Mr Boffin’s motive for saying this? Is it himself or his wife who clings more to their worldly possessions? Does he really want to spare her any worries, or is he afraid she might not want to have anything to do with this blackmail affair and prevail on Boffin to renounce the whole property altogether?

Mr Wegg generously makes this concession to spare Mrs Boffin’s feelings. They have meanwhile gone to Venus’s shop in order to let Mr Boffin have a look at the will that threatens his claim to the Harmon property. I noticed that by now Mr Boffin must have picked up some reading skills because he is able to read the will on his own – even though he does it very slowly and with effort. After Boffin has satisfied (or dissatisfied) himself as to the existence of the will, he is taken home by Mr Wegg, who repeatedly makes him sense his new power by calling him back through the keyhole of his front door.

Before I forget, the last of Mr Wegg’s demands – namely that Rokesmith be dismissed – does not seem to depress Mr Boffin very much.

After the third chapter, which once more fuels our expectations as to how Mr Boffin will get out of his predicament, Chapter 4 tells us of “A Runaway Match”. I can summarize it very quickly: One morning, Mr Wilfer and his daughter sneak out of their house, while Mrs Wilfer and Lavinia are still fast asleep, and they meet young Rokesmith. Then Mr Rokesmith and Bella get married, and Bella posts a letter to her mother in which she tells her the news – implying that her father is completely ignorant of what has happened.

There is not a lot that happens in this chapter but it once more shows Dickens’s genius at presenting even standard situations like weddings in an entertaining, original and very humourous light. It might be interesting to compare this wedding ceremony – e.g. the circle in which it is held and its atmosphere – with the other wedding that takes place in the book, that of the Lammles.

I also wondered about the old sailor with the two wooden legs. Just a coincidence, or does he have something to do with Wegg? A last question: What is going to become of Mr and Mrs Rokesmith? How are they going to earn their living? How is Mrs Wilfer going to react to the news?

I also wondered how Rokesmith could afford such a delicious wedding dinner. After all, he is out of work and when we last met him he did not even have a place to stay. Is it responsible for a man in such a situation to marry a young woman?

There is not a lot that happens in this chapter but it once more shows Dickens’s genius at presenting even standard situations like weddings in an entertaining, original and very humourous light. It might be interesting to compare this wedding ceremony – e.g. the circle in which it is held and its atmosphere – with the other wedding that takes place in the book, that of the Lammles.

I also wondered about the old sailor with the two wooden legs. Just a coincidence, or does he have something to do with Wegg? A last question: What is going to become of Mr and Mrs Rokesmith? How are they going to earn their living? How is Mrs Wilfer going to react to the news?

I also wondered how Rokesmith could afford such a delicious wedding dinner. After all, he is out of work and when we last met him he did not even have a place to stay. Is it responsible for a man in such a situation to marry a young woman?

Tristram wrote: "Hello Friends,

This week, we are starting with the last book of our novel, which is entitled A Turning, and we have got four chapters in front of us, two of which seem to bring a plot-strand into a..."

In this chapter we have Bradley Headstone dressed in the same clothes as Riderhood. One wonders if Headstone found the clothes in Rogue's daughter's shop. In any case, here we have the trope of the look-alike being forwarded once again. First, we had Harmon switching clothes with a sailor and now Headstone is dressing like Riderhood. It might be wise for us to remember the emblematic use of clothes that we saw as Jenny Wren dressed her dolls to look like the upper-class women she saw on the streets as well.

Headstone spots Riderhood's red neckerchief and then wears one himself in order to perfectly match Riderhood's appearance. This fact, plus the curious incident of Headstone's nose repeatedly bleeding is too much of a coincidence not to foreshadow that something else may soon happen that will not be pleasant.

In terms of structure we now have Headstone, Wrayburn, Lizzie Hexam and Rogue Riderhood all in very close proximity. I'm holding onto my chair a bit more tightly.

This week, we are starting with the last book of our novel, which is entitled A Turning, and we have got four chapters in front of us, two of which seem to bring a plot-strand into a..."

In this chapter we have Bradley Headstone dressed in the same clothes as Riderhood. One wonders if Headstone found the clothes in Rogue's daughter's shop. In any case, here we have the trope of the look-alike being forwarded once again. First, we had Harmon switching clothes with a sailor and now Headstone is dressing like Riderhood. It might be wise for us to remember the emblematic use of clothes that we saw as Jenny Wren dressed her dolls to look like the upper-class women she saw on the streets as well.

Headstone spots Riderhood's red neckerchief and then wears one himself in order to perfectly match Riderhood's appearance. This fact, plus the curious incident of Headstone's nose repeatedly bleeding is too much of a coincidence not to foreshadow that something else may soon happen that will not be pleasant.

In terms of structure we now have Headstone, Wrayburn, Lizzie Hexam and Rogue Riderhood all in very close proximity. I'm holding onto my chair a bit more tightly.

Tristram wrote: "The title of the second chapter promises us that “The Golden Dustman Rises a Little“, and I don’t know about you, but I was surely happy to hear that. The scene is Mr Boffin’s house, and our friend..."

Tristram

What a great phrase you used! "...not as refined and flowery, but it smells better." Perfect.

It is good to see an uptick in Mr. Boffin's character. He seems so curmudgeonly lately. In this chapter he does move slightly towards his former benevolent self.

I'm going to miss the Lammles if this is their final appearance. Mrs Lammle especially has presented the reader with a truly intriguing character. Cynical and yet sincere, she has been a refreshing addition to Dickens's usual more placid depictions of women.

One action of Mrs. Lammle interests me very much. In this chapter Dickens tells us that Mrs Lammle "had taken up her parasol from a side table and stood sketching with it on the pattern of the damask cloth, as she had sketched on the pattern of Mr. Twemlow's paper wall." Much earlier in the novel, in Book One, Chapter 10, " The Marriage Contract" we read that the newly-we'd Lammles "had walked in a moody humour; for the lady [the newly-wedded Mrs. Lammle] had prodded little spirit holes in the damp sand before her with her parasol..."

Now, I would think this action of drawing and prodding with her parasol must mean something psychologically, but what?

Dickens frequently gave his characters a noticeable phrase, personality quirk or other identifier to help his readers recall the character from part to part, but this action of Mrs Lammle seems more.

Is it meant to suggest how she wishes her life could have turned out differently, and so now she is reduced to only sketching her lost possibilities in a mechanical manner? Could it mean that she is trying to erase her mistakes in life, noteably her marriage to Mr. Lammle? Is it meant to suggest how she has lost the opportunity to write her own story in life now that she is connected to Mr Lammle?

In any case, an interesting and recurring characteristic.

Tristram

What a great phrase you used! "...not as refined and flowery, but it smells better." Perfect.

It is good to see an uptick in Mr. Boffin's character. He seems so curmudgeonly lately. In this chapter he does move slightly towards his former benevolent self.

I'm going to miss the Lammles if this is their final appearance. Mrs Lammle especially has presented the reader with a truly intriguing character. Cynical and yet sincere, she has been a refreshing addition to Dickens's usual more placid depictions of women.

One action of Mrs. Lammle interests me very much. In this chapter Dickens tells us that Mrs Lammle "had taken up her parasol from a side table and stood sketching with it on the pattern of the damask cloth, as she had sketched on the pattern of Mr. Twemlow's paper wall." Much earlier in the novel, in Book One, Chapter 10, " The Marriage Contract" we read that the newly-we'd Lammles "had walked in a moody humour; for the lady [the newly-wedded Mrs. Lammle] had prodded little spirit holes in the damp sand before her with her parasol..."

Now, I would think this action of drawing and prodding with her parasol must mean something psychologically, but what?

Dickens frequently gave his characters a noticeable phrase, personality quirk or other identifier to help his readers recall the character from part to part, but this action of Mrs Lammle seems more.

Is it meant to suggest how she wishes her life could have turned out differently, and so now she is reduced to only sketching her lost possibilities in a mechanical manner? Could it mean that she is trying to erase her mistakes in life, noteably her marriage to Mr. Lammle? Is it meant to suggest how she has lost the opportunity to write her own story in life now that she is connected to Mr Lammle?

In any case, an interesting and recurring characteristic.

Tristram wrote: "The preceding chapter has shown us how one potential danger – Mr Boffin in the claws and clutches of the Lammles – has been averted, but Chapter 3 has us witness how “The Golden Dustman Sinks Again..."

Boffin is having a rough time with his now former reading muse. More and more Wegg appears to take control of their relationship. I can't believe that we are to see Boffin reduced to ashes by the smarmy Wegg, and yet Boffin seems to be totally defeated.

The casting of Sloppy out of the yard and then "locking him out" is yet another instance of Wegg's ascendant powers. Has anyone else noticed the number of times locks, keys and keyholes have found their way into the narrative? I think we have a major symbol brewing with so many references.

When Boffin, our Golden Dustman laments " Dreadful, dreadful, dreadful! I shall die in a workhouse" I felt my spider-sense tingling. When Dickens is at his most dramatic/melodramatic something is brewing. But what is it?

Boffin is having a rough time with his now former reading muse. More and more Wegg appears to take control of their relationship. I can't believe that we are to see Boffin reduced to ashes by the smarmy Wegg, and yet Boffin seems to be totally defeated.

The casting of Sloppy out of the yard and then "locking him out" is yet another instance of Wegg's ascendant powers. Has anyone else noticed the number of times locks, keys and keyholes have found their way into the narrative? I think we have a major symbol brewing with so many references.

When Boffin, our Golden Dustman laments " Dreadful, dreadful, dreadful! I shall die in a workhouse" I felt my spider-sense tingling. When Dickens is at his most dramatic/melodramatic something is brewing. But what is it?

Ch1

Ch1.

As to the question of Headstone' s clothes mimicking Riderhood's, there are no coincidences in this fact or in the text. Dickens wants us to be as fearful now as we were as kids when the wolf dons grandma's clothes. That quote Tristram includes describes a sunset as if "dyed red" and its aftermath ascending as if "droplets of blood" "guiltily shed".

I thought of the LRRH change of clothes after reading Peter's comment about Harmon putting on the sailor's clothes. (Thanks, Peter.)

And if Dickens hasn't reminded us of how the story began and how consequential a donning of someone else's clothes can be, and that red is the color of blood, he makes the cloth neckerchief dyed red.

LindaH wrote: "Ch1

LindaH wrote: "Ch1.

As to the question of Headstone' s clothes mimicking Riderhood's, there are no coincidences in this fact or in the text. Dickens wants us to be as fearful now as we were as kids when the wolf..."

The issue of the color red is interesting. As fate would have it, I was reading some descriptions of the movie The Sixth Sense. The writer of that movie, M. Night Shamayalan, seems to me to be a person who read and immersed himself in Dickens, and the quote below strikes me as fitting for the movie as it is for OMF:

The color red is intentionally absent from most of the film, but it is used prominently in a few isolated shots for "anything in the real world that has been tainted by the other world" and "to connote really explosively emotional moments and situations".

John wrote: "The color red is intentionally absent from most of the film, but it is used prominently in a few isolated shots for "anything in the real world that has been tainted by the other world" and "to connote really explosively emotional moments and situations".

John wrote: "The color red is intentionally absent from most of the film, but it is used prominently in a few isolated shots for "anything in the real world that has been tainted by the other world" and "to connote really explosively emotional moments and situations". ..."

This reminds me of Schindler's list, another time when the use of the color red was very important:

http://www.oskarschindler.com/13.htm

Peter pointed out three instances of disguise in this novel, namely John Harmon dressing up as a sailor (and as a Secretary, in fact), and Bradley donning clothes that look like Riderhood's. As well as the clothes made by Jenny for her dolls.

We might also add another kind of disguise: Namely that of Bella when living in the Boffin household. In one of the last few chapters we read we saw her leave all those new and costly clothes behind and return into her former life with the clothes she brought with her when she started her new life. Can we infer from this that her time with the Boffins, the expensive clothes she wore there, was also a kind of disguise - a disguise that she took for her real nature and that, through Mr Boffin's attempts at "setting her right" she realized as being wrong, thus finding back to her true nature?

We might also add another kind of disguise: Namely that of Bella when living in the Boffin household. In one of the last few chapters we read we saw her leave all those new and costly clothes behind and return into her former life with the clothes she brought with her when she started her new life. Can we infer from this that her time with the Boffins, the expensive clothes she wore there, was also a kind of disguise - a disguise that she took for her real nature and that, through Mr Boffin's attempts at "setting her right" she realized as being wrong, thus finding back to her true nature?

Peter wrote: "Is it meant to suggest how she wishes her life could have turned out differently, and so now she is reduced to only sketching her lost possibilities in a mechanical manner? ."

I think that this is exactly what lies at the bottom of her using the parasol as some kind of brush. Good observance, Peter!

I think that this is exactly what lies at the bottom of her using the parasol as some kind of brush. Good observance, Peter!

Tristram wrote: "Peter pointed out three instances of disguise in this novel, namely John Harmon dressing up as a sailor (and as a Secretary, in fact), and Bradley donning clothes that look like Riderhood's. As wel..."

Tristram

Yes indeed. Bella is a wonderful example and I do see her clothing as representative of a disguise.

Tristram

Yes indeed. Bella is a wonderful example and I do see her clothing as representative of a disguise.

In the Lock-Keeper's House

Book 4 Chapter 1

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 4, "A Turning," Chapter 1, "Setting Traps," appeared in the August, 1865, installment. The precise moment captured in the illustration must have been at first difficult for the serial reader to determine because there are two such moments in the text, and Stone has provided few clues as to which textual passage is the basis for the illustration of the scene at Plashwater Weir-Mill Lock.

After their initial meeting at the lock on the upper Thames, Rogue Riderhood, now installed as the keeper of the lock, studies the schoolmaster's uncharacteristic mode of dress:

Truly, Bradley Headstone had taken careful note of the honest man's dress in the course of that night-walk they had had together. He must have committed it to memory, and slowly got it by heart. It was exactly reproduced in the dress he now wore. And whereas, in his own schoolmaster clothes, he usually looked as if they were the clothes of some other man, he now looked, in the clothes of some other man or men, as if they were his own.

Having switched his "rusty colourless wisp" of a neckerchief for "a conspicuous bright red neckerchief stained black here and there by wear," Riderhood waits to see if Headstone, when he returns, will take note, and whether he will subsequently make a similar change in his attire (the pages' running heads being "Riderhood's Device,", and "The Test of the Red Neckerchief,".) Sure enough, Headstone returns after ascertaining that Wrayburn has decided to stay the night at an Angler's Inn. Bradley Headstone rests on the cot in the lock-house of Rogue Riderhood before taking up his surveillance of Eugene Wrayburn in hopes of locating Lizzie Hexam.

Riderhood, leaning back in his wooden arm-chair with his arms folded on his breast, looked at him [Headstone] lying with his right hand clenched in his sleep and his teeth set, until a film came over his own sight, and he slept too.

This, at first blush, would appear to be the moment realised. However, such a moment occurs again, three pages later. Headstone then returns after an intervening night and again avails himself of Riderhood's cot and spartan hospitality. On this second occasion, Riderhood notices that Headstone, still dressed in a manner almost identical to Riderhood himself, is now wearing a red bandanna around his neck. That Headstone is attempting to emulate Riderhood's manner of dress so precisely throws the waterman into a "brown study," in which he meditates upon Headstone's possible intentions. On this second night, amidst a lightning storm that serves as an appropriate psychological backdrop for the schoolmaster's vengeful motivations, Riderhood, ignorant of Headstone's plan, studies the sleeper:

Riderhood sat down in his wooden arm-chair, and looked through the window at the lightning, and listened to the thunder. But, his thoughts were far from being absorbed by the thunder and the lightning, for again and again and again he looked very curiously at the exhausted man upon the bed.

Riderhood, again in his armchair, is studying the sleeping schoolmaster as the chapter concludes. Consequently, although the illustration does not suggest the lightning storm outside, the passage from the August instalment realised in this illustration is likely this:

"Softly and slowly, he opened the coat and drew it back.

The draggling ends of a bright-red neckerchief were then disclosed, and he had even been at the pains of dipping parts of it in some liquid, to give it the appearance of having become stained by wear. With a much-perplexed face, Riderhood looked from it to the sleeper, and from the sleeper to it, and finally crept back to his chair, and there, with his hand to his chin, sat long in a brown study, looking at both.

Whether Stone has fulfilled his intention — to engage the reader in the process of detection in order to underscore the importance of the scene in heightening the story's suspense and signalling Headstone's intention to murder Wrayburn — is far more germane to a consideration of the illustration than its technical fidelity to the text as a realisation. The reader, like Riderhood, is instructed by the illustration to consider Headstone's underlying intentions in shadowing Wrayburn as he rows upriver.

Rogue Riderhood recognised his "T'Other Governor," Mr. Eugene Wrayburn

Book 4 Chapter 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

"Plashwater Weir-Mill Lock looked tranquil and pretty on an evening in the summer time. A soft air stirred the leaves of the fresh green trees, and passed like a smooth shadow over the river, and like a smoother shadow over the yielding grass. The voice of the falling water, like the voices of the sea and the wind, were as an outer memory to a contemplative listener; but not particularly so to Mr. Riderhood, who sat on one of the blunt wooden levers of his lock-gates, dozing. Wine must be got into a butt by some agency before it can be drawn out; and the wine of sentiment never having been got into Mr. Riderhood by any agency, nothing in nature tapped him.

As the Rogue sat, ever and again nodding himself off his balance, his recovery was always attended by an angry stare and growl, as if, in the absence of any one else, he had aggressive inclinations towards himself. In one of these starts the cry of "Lock, ho! Lock!" prevented his relapse into a doze. Shaking himself as he got up like the surly brute he was, he gave his growl a responsive twist at the end, and turned his face down-stream to see who hailed.

It was an amateur-sculler, well up to his work though taking it easily, in so light a boat that the Rogue remarked: "A little less on you, and you'd a'most ha' been a Wagerbut;" then went to work at his windlass handles and sluices, to let the sculler in. As the latter stood in his boat, holding on by the boat-hook to the woodwork at the lock side, waiting for the gates to open, Rogue Riderhood recognized his "T'other governor," Mr. Eugene Wrayburn; who was, however, too indifferent or too much engaged to recognize him.

The creaking lock-gates opened slowly, and the light boat passed in as soon as there was room enough, and the creaking lock-gates closed upon it, and it floated low down in the dock between the two sets of gates, until the water should rise and the second gates should open and let it out. When Riderhood had run to his second windlass and turned it, and while he leaned against the lever of that gate to help it to swing open presently, he noticed, lying to rest under the green hedge by the towing-path astern of the Lock, a Bargeman."

Commentary:

Since it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney's 1875 treatment of the textual material is often his response to the original series of illustrations by young Marcus Stone, Dickens's 1860s serial and volume illustrator after Dickens's dropping Hablot Knight Browne, his principal illustrator for twenty-five years. Although Mahoney sometimes accepts Stone's notions, as in Bella 'Righted' by the Golden Dustman and The Lovely Woman has her Fortune told, the pair of illustrations for the July 1865 or fifteenth monthly part in the British serialisation, the Household Edition illustrator had no suitable model with which to open what had originally been one of the novel's most significant serial curtain, the August 1865 number which opens Book Four. Here, however, James Mahoney did not have to invent a wholly new scene; rather, he had several models of the area of the Plashwater Weir Lock from Stone's narrative-pictorial series — although Stone does realise Eugene Wrayburn's passing through the lock now administered by Rogue Riderhood. In particular, Mahoney utilizes certain details in Not to be Shaken Off (November 1865) and, for a useful portrait of Rogue Riderhood at this point, In the Lock-Keeper's House (August 1865).

The Household Edition illustrator does not attempt, as Stone did, to provide a panoramic treatment of the lock on the upper reaches of the Thames; rather, he moves in for the closeup of Eugene in his rowing clothes, holding a boat-hook and watched by the unhappy lock-keeper — "unhappy" because he knows that Wrayburn and his partner, Mortimer Lightwood, specifically did not recommend him for the post at Plashwater Weir. The moment realised, based on the boat-hook and the rower's being turned away from the lock-keeper, is highly specific: "As the latter stood in his boat, holding on by the boat-hook to the woodwork at the lock side, waiting for the gates to open, Rogue Riderhood recognized his 'T'other governor,' Mr. Eugene Wrayburn; who was, however, too indifferent or too much engaged to recognize him", so that one's reading of the illustration in this volume is narrowly analeptic.

Since the lock-keeper's house seems relatively small in one of Stone's illustrations and much more like a substantial cottage in another, Mahoney has elected to provide a small house with a chimney just left of centre, rear. Riderhood, in his signature fur cap, sits on one of the two upper beams of the lock seen in the final Stone illustration. Evidently Riderhood is at the top of the steps, and the water in the lock is much higher here than it is in the Stone illustration. The text clarifies by Riderhood's working the winches that Eugene is going upriver and not down, but Dickens does not make clear by his description of the site and operation of the lock which of the forty-five Thames locks he had in mind. Complicating matters here is the fact that Mahoney seems to have based his lock on Stone's, which is in fact that at Maida Vale on the Regent's Canal (constructed from 1814-1820) in Greater London. Of the river's forty-five locks, twenty-one are associated with weirs, and only four post-date the composition of the novel — and all the locks at the upper end of the river are manually operated, so that no definitive identification of the lock in Our Mutual Friend seems possible, although the lower part of the Penton Hook Lock at Staines is plausible.

"There were actually tears in the bold woman's eyes as the soft-headed and soft-hearted girl twined her arms about her neck"

Book 4 Chapter 2

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"Oh, no, I didn't," cried Georgiana. "It's very impolite, I know, but I came to see my poor Sophronia, my only friend. Oh! how I felt the separation, my dear Sophronia, before I knew you were brought low in the world, and how much more I feel it now!"

There were actually tears in the bold woman's eyes, as the soft-headed and soft-hearted girl twined her arms about her neck.

"But I've come on business," said Georgiana, sobbing and drying her face, and then searching in a little reticule, "and if I don't despatch it I shall have come for nothing, and oh good gracious! what would Pa say if he knew of Sackville Street, and what would Ma say if she was kept waiting on the doorsteps of that dreadful turban, and there never were such pawing horses as ours unsettling my mind every moment more and more when I want more mind than I have got, by pawing up Mr. Boffin's street where they have no business to be. Oh! where is, where is it? Oh! I can't find it!" All this time sobbing, and searching in the little reticule.

"What do you miss, my dear?" asked Mr Boffin, stepping forward.

"Oh! it's little enough," replied Georgiana, "because Ma always treats me as if I was in the nursery (I am sure I wish I was!), but I hardly ever spend it and it has mounted up to fifteen pounds, Sophronia, and I hope three five-pound notes are better than nothing, though so little, so little! And now I have found that — oh, my goodness! there's the other gone next! Oh no, it isn't, here it is!'"

With that, always sobbing and searching in the reticule, Georgiana produced a necklace.

"Ma says chits and jewels have no business together," pursued Georgiana, "and that's the reason why I have no trinkets except this, but I suppose my aunt Hawkinson was of a different opinion, because she left me this, though I used to think she might just as well have buried it, for it's always kept in jewellers' cotton. However, here it is, I am thankful to say, and of use at last, and you'll sell it, dear Sophronia, and buy things with it."

"Give it to me," said Mr. Boffin, gently taking it. "I'll see that it's properly disposed of."

"Oh! are you such a friend of Sophronia's, Mr. Boffin" cried Georgiana. "Oh, how good of you! Oh, my gracious! there was something else, and it's gone out of my head! Oh no, it isn't, I remember what it was. My grandmamma's property, that'll come to me when I am of age, Mr. Boffin, will be all my own, and neither Pa nor Ma nor anybody else will have any control over it, and what I wish to do it so make some of it over somehow to Sophronia and Alfred, by signing something somewhere that'll prevail on somebody to advance them something. I want them to have something handsome to bring them up in the world again. Oh, my goodness me! Being such a friend of my dear Sophronia's, you won't refuse me, will you?"

"No, no," said Mr. Boffin, "it shall be seen to."

"Oh, thank you, thank you!" cried Georgiana. "If my maid had a little note and half a crown, I could run round to the pastrycook's to sign something, or I could sign something in the Square if somebody would come and cough for me to let 'em in with the key, and would bring a pen and ink with 'em and a bit of blotting-paper. Oh, my gracious! I must tear myself away, or Pa and Ma will both find out! Dear, dear Sophronia, good, good-bye!"

The credulous little creature again embraced Mrs. Lammle most affectionately, and then held out her hand to Mr. Lammle.

"Good-bye, dear Mr. Lammle — I mean Alfred. You won't think after to-day that I have deserted you and Sophronia because you have been brought low in the world, will you? Oh me! oh me! I have been crying my eyes out of my head, and Ma will be sure to ask me what's the matter. Oh, take me down, somebody, please, please, please!"

Mr. Boffin took her down, and saw her driven away, with her poor little red eyes and weak chin peering over the great apron of the custard-coloured phaeton, as if she had been ordered to expiate some childish misdemeanour by going to bed in the daylight, and were peeping over the counterpane in a miserable flutter of repentance and low spirits. Returning to the breakfast-room, he found Mrs. Lammle still standing on her side of the table, and Mr. Lammle on his.

Commentary:

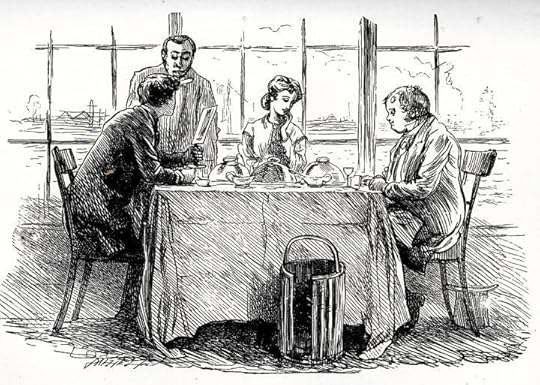

The composite wood-engraving concerns Georgiana Podsnap's bursting into the breakfast-room of the Boffins to commiserate with the "dear" Lammles over their furniture having been sold to meet their promisory note to Pubsey & Co. (Fledgeby) and trying to come to Mrs. Lammles' aid financially. Boffin and his wife at this point are mere observers to the scene, the third principal figure in the breakfast-room being Alfred Lammle (left), looking much as he has done in previous illustrations. The couple's attempt to use their knowledge of Rokesmith's proposal to Bella to manipulate Boffin into discharging the secretary as a fortune-hunter and have Boffin replace him with Alfred Lammle (in order to advance their larger scheme of defrauding Boffin) has failed utterly. Knowing about their scheme, Boffin has just paid them a hundred-pound note for their "services" — and dismissed them. There is no comparable illustration in the original serial series by Marcus Stone.

Mahoney does not attempt to describe Georgiana Podsnap's expression, but merely renders her both short and possessing a disproportionately small head in order to suggest her child-like devotion to Sophronia and her mental vacuity. The real drama has already been enacted before the girl's entrance, as Boffin has confronted the Lammles about their confidence scheme and paid them off for supposedly unmasking Rokesmith, which Boffin describes as their "service." He makes sure that the couple do not even acquire the girl's three five-pound notes and heirloom necklace. Consequently, as the chapter title announces, "The Golden Dustman Rises a Little" in the reader's estimation.

This is our last view of the Lammles in Mahoney's narrative-pictorial sequence, and the picture essentially marks their defeat as confidence artists, confirming in the reader's mind that the fourth book of the novel will resolve the various plot-lines. The group scene is rather different from those earlier illustrations involving the Lammles, the unmasking scene on the shore of the Isle of Wight — She sits upon her stone, and takes no heed of him, and the scene in which the Lammles persuade Georgiana that they are sympathetic friends. The illustrator here is careful not to communicate the outcome of Boffin's confrontation as he has focused on the later scene, after Boffin has given the swindlers their dismissal and their reward. And yet the illustrator shows them cool and self-possessed despite their potential victim's slipping out of their coils.

The Wedding Dinner at Greenwich

Book 4 Chapter 4

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

The "runaway match" alluded to in the chapter title is that of Bella Wilfer and John Rokesmith, who clandestinely meet and are married in the church at Greenwich, with Bella's father, R. W., and a pensioner of the Greenwich Naval Hospital ("Gruff and Glum" as they mentally nickname him) as witnesses. Having informed Mrs. Wilfer of the fact through the penny post, the couple and R. W. enjoy a wedding breakfast at Rokesmith's rented cottage on Blackheath, not far from Greenwich in Lewisham (curiously enough, the site is associated with Wat Tyler's ill-fated rebellion, to which Dickens alludes earlier in the installment — Book Four, Chapter One). Later in the day, in a scene chosen by Marcus Stone as the subject of the second August 1865 illustration, the newlyweds and the "Cherub," Bella's father, have a celebratory dinner at a hotel in Greenwich overlooking the Thames, the connecting thread between so many characters and situations in the novel. The precise moment depicted is the groom's consulting the head waiter about beverages to be served with the ensuing meal, the day's offerings of wine and spirits presumably being on the list that John Rokesmith holds in his left hand as he confers with the waiter:

"The appearance of dinner here cut Bella short in one of her disappearances: the more effectually, because it was put on under the auspices of a solemn gentleman in black clothes and a white cravat, who looked much more like a clergyman than the clergyman, and seemed to have mounted a great deal higher in the church: not to say, scaled the steeple. This dignitary, conferring in secrecy with John Rokesmith on the subject of punch and wines, bent his head as though stooping to the Papistical practice of receiving auricular confession. Likewise, on John's offering a suggestion which didn't meet his views, his face became overcast and reproachful, as enjoining penance."

Again, the charm and vivacity of Dickens's prose is not adequately reflected in Stone's composition, and the humorous sentiments on the conduct of the elder and younger waiters are entirely absent — in fact, the awkward understudy of "the Archbishop of Greenwich" does not appear at all in the dining scene. The whole piece in the text is a delicate farce, but the otherwise realistic drawing of the wedding dinner lacks even a suggestion of comedy. Bella, turning aside From her husband's deliberations with the waiter, seems strangely isolated, and the "cherub" lacks any animation. Stone has patiently recorded the details given and invented others such as the salvers that are plausible enough, but the reader may well complain that Stone could have selected a far more entertaining moment in the proceedings of the wedding dinner for elaboration, particularly Bella's attempting to create the impression (despite her obvious happiness) that they have enjoyed a number of anniversary celebrations prior to this.

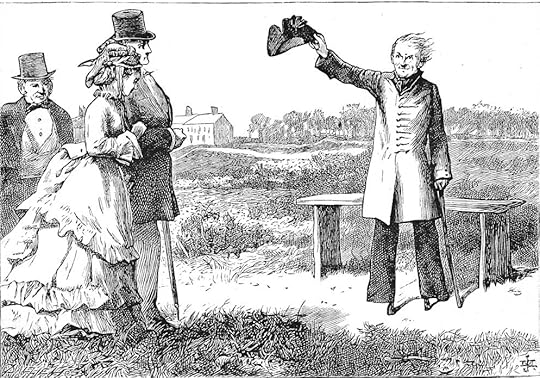

Book 4 Chapter 4

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

At least, Bella no sooner stepped ashore than she took Mr. John Rokesmith's arm, without evincing surprise, and the two walked away together with an ethereal air of happiness which, as it were, wafted up from the earth and drew after them a gruff and glum old pensioner to see it out. Two wooden legs had this gruff and glum old pensioner, and, a minute before Bella stepped out of the boat, and drew that confiding little arm of hers through Rokesmith's, he had had no object in life but tobacco, and not enough of that. Stranded was Gruff and Glum in a harbour of everlasting mud, when all in an instant Bella floated him, and away he went.

Say, cherubic parent taking the lead, in what direction do we steer first? With some such inquiry in his thoughts, Gruff and Glum, stricken by so sudden an interest that he perked his neck and looked over the intervening people, as if he were trying to stand on tiptoe with his two wooden legs, took an observation of R. W. There was no 'first' in the case, Gruff and Glum made out; the cherubic parent was bearing down and crowding on direct for Greenwich church, to see his relations.

For, Gruff and Glum, though most events acted on him simply as tobacco-stoppers, pressing down and condensing the quids within him, might be imagined to trace a family resemblance between the cherubs in the church architecture, and the cherub in the white waistcoat. Some remembrance of old Valentines, wherein a cherub, less appropriately attired for a proverbially uncertain climate, had been seen conducting lovers to the altar, might have been fancied to inflame the ardour of his timber toes. Be it as it might, he gave his moorings the slip, and followed in chase.

The cherub went before, all beaming smiles; Bella and John Rokesmith followed; Gruff and Glum stuck to them like wax. For years, the wings of his mind had gone to look after the legs of his body; but Bella had brought them back for him per steamer, and they were spread again.

. . . .Who taketh? I, John, and so do I, Bella. Who giveth? I, R. W. Forasmuch, Gruff and Glum, as John and Bella have consented together in holy wedlock, you may (in short) consider it done, and withdraw your two wooden legs from this temple. To the foregoing purport, the Minister speaking, as directed by the Rubric, to the People, selectly represented in the present instance by G. and G. above mentioned.

And now, the church-porch having swallowed up Bella Wilfer for ever and ever, had it not in its power to relinquish that young woman, but slid into the happy sunlight, Mrs. John Rokesmith instead. And long on the bright steps stood Gruff and Glum, looking after the pretty bride, with a narcotic consciousness of having dreamed a dream.

. . . . Then they, all three, out for a charming ride, and for a charming stroll among heath in bloom, and there behold the identical Gruff and Glum with his wooden legs horizontally disposed before him, apparently sitting meditating on the vicissitudes of life! To whom said Bella, in her light-hearted surprise: "Oh! How do you do again? What a dear old pensioner you are!" To which Gruff and Glum responded that he see her married this morning, my Beauty, and that if it warn't a liberty he wished her ji and the fairest of fair wind and weather; further, in a general way requesting to know what cheer? and scrambling up on his two wooden legs to salute, hat in hand, ship-shape, with the gallantry of a man-of-warsman and a heart of oak.

It was a pleasant sight, in the midst of the golden bloom, to see this salt old Gruff and Glum, waving his shovel hat at Bella, while his thin white hair flowed free, as if she had once more launched him into blue water again. "You are a charming old pensioner," said Bella, "and I am so happy that I wish I could make you happy, too." Answered Gruff and Glum, "Give me leave to kiss your hand, my Lovely, and it's done!" So it was done to the general contentment; and if Gruff and Glum didn't in the course of the afternoon splice the main brace, it was not for want of the means of inflicting that outrage on the feelings of the Infant Bands of Hope.

Commentary:

Mahoney does not attempt to describe the wedding dinner since the subject of the wedding of John (who has yet to reveal his true identity as John Harmon) and Bella had been dealt with (albeit in a lackluster fashion) by Marcus Stone ten years earlier in The Wedding Dinner at Greenwich (August 1865). The focal character is not a member of the small wedding-party at all, but the witness, a double-amputee who serves as the Rokesmiths' witness in the ceremony, which probably occurs at the local Anglican church, St. Alfege's, although Dickens does not identify the church by name and the church tower just above the tree-line in the Mahoney illustration is square rather than the delicate spire of Hawksmoor's elegant neo-classical design.

A touch of local color — the most interesting feature of the illustration — is the uniformed Naval Hospital veteran (an "in-pensioner") who salutes the bride and groom after the ceremony with due nautical terminology and a wave of his tricorn hat. There is no comparable illustration in the original serial series by Marcus Stone, who elected to show the wedding dinner in The Ship Inn for the fourth book's fourth chapter, "A Runaway Match," originally in the August 1865 serial installment. The old salt, a pensioner of the nearby Greenwich Naval Hospital ("Gruff and Glum" as the couple mentally nickname him) serves as the witness for the ceremony. Four years after the publication of the novel, the custom of providing on-site care for as many as two thousand old salts (retired sailors and royal marines) in their blue frock-coats and tricorn hats (similar to the red uniforms of the Chelsea pensioners) ceased as an economy. In October 1865, just as Our Mutual Friend was winding up its serial run, under a new Act, 987 of the 1400 remaining in-pensioners left the Hospital, and in 1869 the Greenwich Naval Hospital closed, shortly to become the Greenwich Naval College for officers of the Royal Navy just two years ahead of the publication of the Household Edition volume. Mahoney's including the scene with the cheering in-pensioner instead of the couple and R. W. at the wedding dinner may constitute a bit of late Victorian nostalgia, and certainly serves as a chronological and geographical allusion to the era and locale in which this part of the story unfolds.

Kim wrote: "In the Lock-Keeper's House

Book 4 Chapter 1

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 4, "A Turning," Chapter 1, "Setting Traps," appeared in the August, 1865, installment. The pre..."

Rogue Riderhood looks the part of a rough and tumble man. The innocent (?!) sleeper Headstone is apparently unaware of the vulture that hovers over him. Is the sleep of the innocent transitory and misleading?

To me this illustration would direct the reader to be suspicious of Riderhood's intentions since we already know he was capable of extracting money from even the innocent Betty. And yet, as readers, we also know that Headstone is capable of much evil.

Who will prevail from this duo?

Book 4 Chapter 1

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 4, "A Turning," Chapter 1, "Setting Traps," appeared in the August, 1865, installment. The pre..."

Rogue Riderhood looks the part of a rough and tumble man. The innocent (?!) sleeper Headstone is apparently unaware of the vulture that hovers over him. Is the sleep of the innocent transitory and misleading?

To me this illustration would direct the reader to be suspicious of Riderhood's intentions since we already know he was capable of extracting money from even the innocent Betty. And yet, as readers, we also know that Headstone is capable of much evil.

Who will prevail from this duo?

Kim wrote: "

Book 4 Chapter 4

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

At least, Bella no sooner stepped ashore than she took Mr. John Rokesmith's arm, without evincing surprise, and the two..."

I was totally unaware of the information about how old Gruff and Glum fit the narrative as a comment on the "in-pensioners" in England. Very interesting to see how this small portion of the novel actually makes a strong social comment. Given the amount of time and focus money has received in the novel it seems likely that Dickens was very deliberate in this chapter.

Also, what, if anything, might be the connection or comment that is inherent with having two people who are crippled because of a loss of limbs? Wegg has one artificial leg and Gruff and Flum has two?

Book 4 Chapter 4

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

At least, Bella no sooner stepped ashore than she took Mr. John Rokesmith's arm, without evincing surprise, and the two..."

I was totally unaware of the information about how old Gruff and Glum fit the narrative as a comment on the "in-pensioners" in England. Very interesting to see how this small portion of the novel actually makes a strong social comment. Given the amount of time and focus money has received in the novel it seems likely that Dickens was very deliberate in this chapter.

Also, what, if anything, might be the connection or comment that is inherent with having two people who are crippled because of a loss of limbs? Wegg has one artificial leg and Gruff and Flum has two?

If I read the commentary correctly, there were as many as two thousand "old salts" - retired sailors and royal marines - having on-site care, but four years after OMF was published on-site care ceased as an economy. The 1400 remaining in-pensioners left the Hospital, and in 1869 the Greenwich Naval Hospital closed. Where did these 1400 retired sailors go?

That's a question leading to probably grim speculations, Kim. Maybe, in the course of the four years, not few of them died. I would think so because after all, they were ancient mariners, who must have been quite old, and probably their health was affected in many serious ways. And then, with not many of the "old salts" remaining, they were probably taken care of in other institutions. Hopefully.

As to Riderhood, I don't see him in any of the illustrations. To my mind, he appears more haggard, lanky but brawny and not so much as the thick-set fellow we see here. After all, isn't he a bird of prey?

Tristram wrote: "That's a question leading to probably grim speculations, Kim. Maybe, in the course of the four years, not few of them died. I would think so because after all, they were ancient mariners, who must ..."

Once, after one of our Wednesday nights singing at a nursing home I got talking to one of the ladies sitting with her husband who had had a number of strokes and was now in a wheelchair all the time. They are both in their 80s I think. I asked her if he liked the home and she told me he Iiked it very much. She was worried though what she would do when their money ran out, she didn't think she could take care of him at home. I was puzzled and asked her why she would have to take him home and she said they only let you stay until your money runs out. If this is true, and other members of my group say it isn't, I'm wondering how the people running the home can live with that. There must be some way for some kind of funding to keep those people there. Oh, so far he's still there.

Once, after one of our Wednesday nights singing at a nursing home I got talking to one of the ladies sitting with her husband who had had a number of strokes and was now in a wheelchair all the time. They are both in their 80s I think. I asked her if he liked the home and she told me he Iiked it very much. She was worried though what she would do when their money ran out, she didn't think she could take care of him at home. I was puzzled and asked her why she would have to take him home and she said they only let you stay until your money runs out. If this is true, and other members of my group say it isn't, I'm wondering how the people running the home can live with that. There must be some way for some kind of funding to keep those people there. Oh, so far he's still there.

Kim wrote: "If I read the commentary correctly, there were as many as two thousand "old salts" - retired sailors and royal marines - having on-site care, but four years after OMF was published on-site care cea..."

Dare we consider they all had stalls in London and sold ballads, newspapers and became the "watchpeople" of other's houses.

Dare we consider they all had stalls in London and sold ballads, newspapers and became the "watchpeople" of other's houses.

Kim wrote: "Once, after one of our Wednesday nights singing at a nursing home..."

Kim wrote: "Once, after one of our Wednesday nights singing at a nursing home..."Kim - I see two scenarios. My dad's place had a benevolent fund that residents, families, etc. could donate to that would help support any resident whose funds ran out.

In the case of those places that have no such charity, I would think that the resident would have to be moved to a county facility. In my county, that would not be a happy fate. :-(

It varies here too, Kim. Some nursing homes, or care homes (for those who don't need much medical help or nursing) are completely private, and residents cannot live there any more if their money runs out. Sometimes others (often family members) pay the fees. Then there are homes which are financed by charities and trusts. Then there are a few funded by the National Health Service, but these are getting to be few and far between.

It varies here too, Kim. Some nursing homes, or care homes (for those who don't need much medical help or nursing) are completely private, and residents cannot live there any more if their money runs out. Sometimes others (often family members) pay the fees. Then there are homes which are financed by charities and trusts. Then there are a few funded by the National Health Service, but these are getting to be few and far between.

I must say I thoroughly enjoyed these chapters as there was so much variety! It made me intrigued and chilled - yet I also found myself laughing out loud at times. Like others, I feel many of the strands are now coming together, and also there's quite a bit of foreshadowing of further dark events.

I must say I thoroughly enjoyed these chapters as there was so much variety! It made me intrigued and chilled - yet I also found myself laughing out loud at times. Like others, I feel many of the strands are now coming together, and also there's quite a bit of foreshadowing of further dark events. I was gripped by Bradley Headstone's descending even further into his obsession or madness - or is it an identifiable illness, perhaps? I'm think of the blood in his nose ... So many of the conditions Dickens writes about are genuine, or thought to be genuine at the time, such as (view spoiler) we read about in Bleak House.

Great mystery and suspense here, and I particularly liked the way it's a character we don't really expect to be thinking in an analytical way, who reveals it to us. I'm liking the portrayal of Rogue Riderhood very much. On the one hand he is canny, donning a red neckerchief (and what a great colour to choose, to signal to us how dangerous this whole episode is likely to be!) and on the other hand, he's superstitious (not worried about falling into the weir because he believes that a man who has once nearly drowned, can never be actually drowned.) This seems spot on for characterisation.

Great mystery and suspense here, and I particularly liked the way it's a character we don't really expect to be thinking in an analytical way, who reveals it to us. I'm liking the portrayal of Rogue Riderhood very much. On the one hand he is canny, donning a red neckerchief (and what a great colour to choose, to signal to us how dangerous this whole episode is likely to be!) and on the other hand, he's superstitious (not worried about falling into the weir because he believes that a man who has once nearly drowned, can never be actually drowned.) This seems spot on for characterisation.

I'll be sorry to see the Lammleses go, and feel just a little sorry for Sophronia, who has the worse part of it. There have been repeated signs that she was having an internal moral struggle.

I'll be sorry to see the Lammleses go, and feel just a little sorry for Sophronia, who has the worse part of it. There have been repeated signs that she was having an internal moral struggle.

Chapter 3 really surprised me! Perhaps it shouldn't have, as we knew of Silas Wegg's plans, but the power shift with Wegg now reigning supreme and Noddy Boffin now so chastened, seemed to happen very quickly. The fact that they both seem to think it's a good idea for Rokesmith to be given the push may prove to be quite useful in terms of the plot. Very neat.

Chapter 3 really surprised me! Perhaps it shouldn't have, as we knew of Silas Wegg's plans, but the power shift with Wegg now reigning supreme and Noddy Boffin now so chastened, seemed to happen very quickly. The fact that they both seem to think it's a good idea for Rokesmith to be given the push may prove to be quite useful in terms of the plot. Very neat.And chapter 4 was just a delight from beginning to end. There's trickery, and secrets, but they are all presented in such a goodhearted way, it was a joy to read. Dickens at his best :)

This week, we are starting with the last book of our novel, which is entitled A Turning, and we have got four chapters in front of us, two of which seem to bring a plot-strand into a calmer harbour, whereas the two others are definitely announcements of new, and darker, troubles ahead. Chapter 1 warns us that somebody is “Setting Traps”, and the setting is Plashwater Weir Mill Lock, where Rogue Riderhood is now doing the duty as a lock. The description of the scenery already gives us a hint that Rogue is still as of old and that his has not learned anything from his brush with death:

Rogue’s rest is interrupted by – guess who – Eugene Wrayburn coming in his boat along the river and wanting to pass the weir. Unlike Riderhood, Wrayburn does not immediately recognize with whom he has to do – a sign of his indifference, or of his mind’s being bent on something else – but when he does, he does not refrain from giving Riderhood a very special compliment. Riderhood notices that not far off, there is a bargeman observing the altercation. As soon as Eugene Wrayburn continues his journey, this bargeman approaches, and Riderhood recognizes in him Bradley Headstone. He also notices something else:

Is it just a coincidence that Bradley has copied the clothes of his new friend, or a sign of the teacher’s lack of imagination – in the sense that he wants to pass for a bargeman and simply copied the only bargeman he knew? Or may Bradley have quite another reason for his disguise?

The two men start talking about their common enemy, and why not? There is nothing that can bring up a feeling of togetherness between two people who have little else in common than finding out they dislike the same person or thing. Only, Bradley gets very, very worked up when he learns how Eugene has insulted Riderhood – and he probably does not take it to heart on Riderhood’s behalf.

That does not sound too good for Wrayburn! Riderhood learns from Bradley that Wrayburn is undoubtedly on his way to Lizzie’s whereabouts and that this time, Bradley will finally see those two together. The schoolmaster renews his pact with Riderhood by giving him two pounds – again the lock keeper shows his impertinence here by making the offer of one pound an offer of two. Then Bradley resumes his chase of his target person, and we are given another ill omen:

Riderhood meanwhile starts ruminating on why Bradley copied his clothes, and in order to find out whether it was a coincidence or not, he puts on a red neckerchief. When later Bradley returns in order to get some sleep at the lock – before continuing his chase (Wrayburn, too, has turned in at the riverside for the night) –, Riderhood makes sure that Bradley notices this new addition to his outfit. The two men also talk about the impossibility of ever getting out of the weir without any help, once one has fallen into it:

Riderhood, however, is not worried about falling into the weir because in his opinion, a man who has nearly drowned can never fall prey to the river’s hunger again. In the morning, Bradley once more starts on his self-appointed mission, and Riderhood just waits for him to return. When he finally does after another day, the weather has changed – there is a storm, as there usually is in such dramatic moments, and Bradley is even more of a human ruin than he already was. He is so excited and distraught that blood gushes from his nose, and Riderhood learns that this has not happened the first time in the last few hours. Bradley decides to get some sleep again, and his host notices that he has carefully buttoned up his jacket. With ever so gingerly hands, Ridehood examines the sleeping man’s throat in order to find that lo! there is now also a red neckerchief around Bradley’s neck. The rest of the night, Riderhood spends in a brown study, musing on his sleeping guest and whatever intentions he might entertain.