The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The Federalist Papers

THE FEDERALIST PAPERS

>

WE ARE OPEN - Week Sixteen - April 27th - May 3rd (2020) - FEDERALIST. NO 69

message 2:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 25, 2019 05:30PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Now we find ourselves on Federalist 69.

We are moving towards some of the more poignant essays regarding our times. We will of course go back to the others.

We will always continue to move on; but please also feel free to get caught up and post any of your thoughts on this paper and/or on any of the other papers which were assigned from weeks past.

There is a ton of stuff to discuss about Federalist Papers 1 - 15 even though we are opening up discussion on the next paper today and we are selecting some papers that are apropos to the current climate.

We have to keep moving no matter if it takes us 170 weeks of 340 weeks for the 85 essays and we will get them all read and completed with discussions.

Please feel free to post on any of the other 15 previous essays that we have worked very hard on - Federalist 1 - 15. And then try your hand at Federalist 69. The essays make for very interesting reading.

FEDERALIST No. 69

Federalist № 69

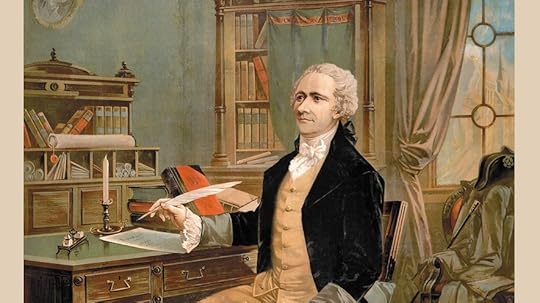

The Real Character of the Executive (Alexander Hamilton)

November 25th - December 7th but this is ON-GOING

Links to 69:

http://federali.st/69

You can also listen to them being read orally to you:

Federalist 69 audio:

LibraVox

http://www.archive.org/download/feder...

Federalist Papers - Access page - scroll down to the bottom:

A much better oral reading:

http://michaelscherervoice.com/federa...

We are moving towards some of the more poignant essays regarding our times. We will of course go back to the others.

We will always continue to move on; but please also feel free to get caught up and post any of your thoughts on this paper and/or on any of the other papers which were assigned from weeks past.

There is a ton of stuff to discuss about Federalist Papers 1 - 15 even though we are opening up discussion on the next paper today and we are selecting some papers that are apropos to the current climate.

We have to keep moving no matter if it takes us 170 weeks of 340 weeks for the 85 essays and we will get them all read and completed with discussions.

Please feel free to post on any of the other 15 previous essays that we have worked very hard on - Federalist 1 - 15. And then try your hand at Federalist 69. The essays make for very interesting reading.

FEDERALIST No. 69

Federalist № 69

The Real Character of the Executive (Alexander Hamilton)

November 25th - December 7th but this is ON-GOING

Links to 69:

http://federali.st/69

You can also listen to them being read orally to you:

Federalist 69 audio:

LibraVox

http://www.archive.org/download/feder...

Federalist Papers - Access page - scroll down to the bottom:

A much better oral reading:

http://michaelscherervoice.com/federa...

message 3:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 25, 2019 05:34PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

How to conquer the Federalist Papers:

1. The first thing I would do is to read along with an audio recording for a quick pass through the paper for the first time. The audio helps you get through each essay and you can underline as you listen and read. Also it is best to tackle each essay one at a time. Do not try to read through all 85 essays without discussion - most folks have found that it is tedious and they do not get through the essays that way. Most colleges only tackle a handful of the papers and rely on students to read the others on their own.

2. The next thing that you should do is to do a deep dive: one paragraph at a time studying every facet of the essay. You are fortunate that we will do the researching for you and will journey with you as we tackle this project. One paragraph at a time until we get through the entire essay.

3. You should always be asking yourself the following questions:

a) Who wrote this essay? What was their background and who were they? What is their frame of reference? What are they trying to persuade me to believe and why and how are they trying to accomplish this? Is what they are saying true? If so, where is the supporting evidence? What are the arguments being made against this essay?

2. The Federalist Papers will give you an idea of why something in the Constitution is the way it is. However, be mindful that as we found in Federalist 14 - an item or two might not have made it into the Constitution and might have been voted down; so it might have been wishful thinking on the part of the essayist. However, so far - that has rarely been the case. So query, where in the Constitution is this fact and idea mentioned and how or why?

3. Try to understand the context under which the essay was written. Context is important to understanding anything you read, hear or see for that matter. How do you think it was received? Who opposed it and what were their viewpoints? Reflect upon both sides. Allow the Federalist Papers the opportunity to speak for themselves.

4. Look and ponder the meaning of the words being used and the arguments that the Founding Fathers are making. Possibly jot those down or underline them for further consideration.

5. You might want to go deep with a few supporting primary sources and then dabble by looking at some additional videos, listening to some podcasts or reading other material to support your views; but, at the same time, be sure not to block out any opposing ones for consideration - which may challenge your thinking. Challenging your thinking is positive and who knows you might change your mind or modify a position or be willing to compromise and see that others have a point of view that has merit.

6. You should ask yourself with each essay - what does the essay say - what is the essayist trying to tell me? Do I understand what the essayist is saying? What parts do I need more clarification on? What is the argument or the concept the Founding Fathers are proposing? What is the institution or proposal that they are defending? Why?

7. What does the essay mean to me? Do I know the meaning of all of the words used in the essay? If not, look them up as you are reading or listening. Words matter. Try to understand what are the major points or themes of each essay.

8. Why does this essay matter? How is it relevant to me? How is it relevant to the country? What has been the history of this essay? What was its impact at the time? What is its impact in history or what is its impact in our current environment and times? Have these ideas or sections of the Constitution been challenged? By whom? What was the outcome? Do I agree with these ideas? Do I agree with some and not others? What is the factual evidence for my beliefs? Are they grounded by solid facts, readings, primary sources? Why do they argue some aspects of the Constitution and not others? Sometimes what is omitted in a persuasive essay, speech or other commentary or document is as important as what it said, written or discussed. For example, the word slavery is never used outright in the Constitution even though - by the use and the meaning of some of the Constitution's language we certainly know what is being spoken of.

9. And, of course, the best way to tackle the Federalist Papers is in a group and among friends who will discuss with you their ideas and arguments - pro or con - in a respectful and civl way. There are no wrong answers and once you have made your point - move on to another. These threads are your group of friends. Here we will have a civil and a respectful discussion. There are no worries. So just jump right in and post. The more you post, the better the discussion. If the moderator needs to step in, they always will. Everyone should be respectful of each other and the moderator as if you were all sitting together in someone's living room having a nice discussion face to face. Act as if we knew who you are, where you lived and act as if you were a member of the family who we cared about. We care about each member in the History Book Club and we want everyone to feel comfortable.

10. Also, post - post - post.

1. The first thing I would do is to read along with an audio recording for a quick pass through the paper for the first time. The audio helps you get through each essay and you can underline as you listen and read. Also it is best to tackle each essay one at a time. Do not try to read through all 85 essays without discussion - most folks have found that it is tedious and they do not get through the essays that way. Most colleges only tackle a handful of the papers and rely on students to read the others on their own.

2. The next thing that you should do is to do a deep dive: one paragraph at a time studying every facet of the essay. You are fortunate that we will do the researching for you and will journey with you as we tackle this project. One paragraph at a time until we get through the entire essay.

3. You should always be asking yourself the following questions:

a) Who wrote this essay? What was their background and who were they? What is their frame of reference? What are they trying to persuade me to believe and why and how are they trying to accomplish this? Is what they are saying true? If so, where is the supporting evidence? What are the arguments being made against this essay?

2. The Federalist Papers will give you an idea of why something in the Constitution is the way it is. However, be mindful that as we found in Federalist 14 - an item or two might not have made it into the Constitution and might have been voted down; so it might have been wishful thinking on the part of the essayist. However, so far - that has rarely been the case. So query, where in the Constitution is this fact and idea mentioned and how or why?

3. Try to understand the context under which the essay was written. Context is important to understanding anything you read, hear or see for that matter. How do you think it was received? Who opposed it and what were their viewpoints? Reflect upon both sides. Allow the Federalist Papers the opportunity to speak for themselves.

4. Look and ponder the meaning of the words being used and the arguments that the Founding Fathers are making. Possibly jot those down or underline them for further consideration.

5. You might want to go deep with a few supporting primary sources and then dabble by looking at some additional videos, listening to some podcasts or reading other material to support your views; but, at the same time, be sure not to block out any opposing ones for consideration - which may challenge your thinking. Challenging your thinking is positive and who knows you might change your mind or modify a position or be willing to compromise and see that others have a point of view that has merit.

6. You should ask yourself with each essay - what does the essay say - what is the essayist trying to tell me? Do I understand what the essayist is saying? What parts do I need more clarification on? What is the argument or the concept the Founding Fathers are proposing? What is the institution or proposal that they are defending? Why?

7. What does the essay mean to me? Do I know the meaning of all of the words used in the essay? If not, look them up as you are reading or listening. Words matter. Try to understand what are the major points or themes of each essay.

8. Why does this essay matter? How is it relevant to me? How is it relevant to the country? What has been the history of this essay? What was its impact at the time? What is its impact in history or what is its impact in our current environment and times? Have these ideas or sections of the Constitution been challenged? By whom? What was the outcome? Do I agree with these ideas? Do I agree with some and not others? What is the factual evidence for my beliefs? Are they grounded by solid facts, readings, primary sources? Why do they argue some aspects of the Constitution and not others? Sometimes what is omitted in a persuasive essay, speech or other commentary or document is as important as what it said, written or discussed. For example, the word slavery is never used outright in the Constitution even though - by the use and the meaning of some of the Constitution's language we certainly know what is being spoken of.

9. And, of course, the best way to tackle the Federalist Papers is in a group and among friends who will discuss with you their ideas and arguments - pro or con - in a respectful and civl way. There are no wrong answers and once you have made your point - move on to another. These threads are your group of friends. Here we will have a civil and a respectful discussion. There are no worries. So just jump right in and post. The more you post, the better the discussion. If the moderator needs to step in, they always will. Everyone should be respectful of each other and the moderator as if you were all sitting together in someone's living room having a nice discussion face to face. Act as if we knew who you are, where you lived and act as if you were a member of the family who we cared about. We care about each member in the History Book Club and we want everyone to feel comfortable.

10. Also, post - post - post.

message 4:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 30, 2020 05:25PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Essay Overview and Summary - FEDERALIST. NO 69:

In this essay, Hamilton presents a lengthy comparison and contrast between the president's powers under the new Constitution and the power of the British king.

The president is elected by the people while the British monarchy is hereditary. The president is subject to impeachment for treason, bribery, or other "high crimes or misdemeanors," whereas the person of the king is sacred. The veto power of the president is limited, in that both houses of Congress may override a presidential veto by a two-thirds vote; by contrast the king possesses an absolute veto over acts of Parliament.

The president is commander-in-chief of the armed forces of the United States; the king, however, possesses significantly more military power in that he is authorized to declare war and to raise and maintain armies.

Likewise, in the areas of treaties, appointments, and pardons, the president is in every respect a less powerful governmental officer than the British king.

Hamilton adds that the president may, indeed, be more restricted in his constitutional powers than the governor of New York!

Source: Course Hero

Discussion Question:

1. What are some of your thoughts about the fact that the President in some respects is more restricted in his constitutional powers than the governor of New York or any governor for that matter?

In this essay, Hamilton presents a lengthy comparison and contrast between the president's powers under the new Constitution and the power of the British king.

The president is elected by the people while the British monarchy is hereditary. The president is subject to impeachment for treason, bribery, or other "high crimes or misdemeanors," whereas the person of the king is sacred. The veto power of the president is limited, in that both houses of Congress may override a presidential veto by a two-thirds vote; by contrast the king possesses an absolute veto over acts of Parliament.

The president is commander-in-chief of the armed forces of the United States; the king, however, possesses significantly more military power in that he is authorized to declare war and to raise and maintain armies.

Likewise, in the areas of treaties, appointments, and pardons, the president is in every respect a less powerful governmental officer than the British king.

Hamilton adds that the president may, indeed, be more restricted in his constitutional powers than the governor of New York!

Source: Course Hero

Discussion Question:

1. What are some of your thoughts about the fact that the President in some respects is more restricted in his constitutional powers than the governor of New York or any governor for that matter?

message 5:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 25, 2019 05:48PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

COMMENTARY

Impeachment and High Crimes and Misdemeanors - Two Different Questions by Kenneth Kopf

The U.S. Constitution - Article 2, Section 4, “The President, Vice President, and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

Link: https://www.cnsnews.com/commentary/ke...

Discussion Question:

1. What is your viewpoint of the article in relation to Federalist. No 69? Do you agree with this article and the author's positions or not? Why or why not?

Fractured Into Factions? What The Founders Feared About Impeachment by Jessica Taylor

Source: NPR

As the Founding Fathers were drafting the U.S. Constitution, they were explicitly trying to avoid a repeat of the situation they had just fought a war to free themselves from — a ruler with unchecked power.

While they wrote a bare minimum about impeachment in the country's essential governing document, other writings from the time provide rich insights about their intentions.

In Federalist No. 69, Alexander Hamilton described impeachment essentially as a release valve from another "crisis of a national revolution." He and other Founders grappled with how best to execute such a check, and eventually they settled on the system we have today.

Trump Impeachment Inquiry

Even more than 230 years ago, they were eerily prescient in fearing how the impeachment process could play out: beset by partisanship and broken down by factions. Every impeachment proceeding so far — from Andrew Johnson to Bill Clinton and now President Trump — was split along those lines.

Why was impeachment so important to the Founders?

To understand the Founders' rationale for impeachment first requires an examination of their feelings about the presidency. Hamilton (yes, that one) actually wanted a more robust chief executive, but he did realize there needed to be some check on their power. That's why he would argue in The Federalist Papers for why impeachment should be included in the Constitution.

According to preeminent Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, Hamilton was trying to protect the country from someone with demagogic tendencies. "From the outset, Hamilton feared an unholy trinity of traits in a future president — ambition, avarice and vanity," Chernow wrote last month in The Washington Post.

As Impeachment Inquiry Moves Into Open Phase, Here's What To Expect Next

He points to one of Hamilton's writings in 1792 where the Treasury secretary warns about someone who might exhibit those inclinations, and Chernow argues that it sounds a lot like the current occupant of the Oval Office:

"When a man unprincipled in private life[,] desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper . . . despotic in his ordinary demeanour — known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty — when such a man is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity — to join in the cry of danger to liberty — to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government & bringing it under suspicion — to flatter and fall in with all the non sense of the zealots of the day — It may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may 'ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.'"

Remainder of article:

https://www.npr.org/2019/11/18/779938...

Discussion Question:

1. Read the article and discuss any points you would like regarding current politics and the importance of the founders' words and concerns. Cite the article - lines - quotes - etc. so that we can understand readily your post. Remember to be civil and respectful.

Source: NPR

As the Founding Fathers were drafting the U.S. Constitution, they were explicitly trying to avoid a repeat of the situation they had just fought a war to free themselves from — a ruler with unchecked power.

While they wrote a bare minimum about impeachment in the country's essential governing document, other writings from the time provide rich insights about their intentions.

In Federalist No. 69, Alexander Hamilton described impeachment essentially as a release valve from another "crisis of a national revolution." He and other Founders grappled with how best to execute such a check, and eventually they settled on the system we have today.

Trump Impeachment Inquiry

Even more than 230 years ago, they were eerily prescient in fearing how the impeachment process could play out: beset by partisanship and broken down by factions. Every impeachment proceeding so far — from Andrew Johnson to Bill Clinton and now President Trump — was split along those lines.

Why was impeachment so important to the Founders?

To understand the Founders' rationale for impeachment first requires an examination of their feelings about the presidency. Hamilton (yes, that one) actually wanted a more robust chief executive, but he did realize there needed to be some check on their power. That's why he would argue in The Federalist Papers for why impeachment should be included in the Constitution.

According to preeminent Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, Hamilton was trying to protect the country from someone with demagogic tendencies. "From the outset, Hamilton feared an unholy trinity of traits in a future president — ambition, avarice and vanity," Chernow wrote last month in The Washington Post.

As Impeachment Inquiry Moves Into Open Phase, Here's What To Expect Next

He points to one of Hamilton's writings in 1792 where the Treasury secretary warns about someone who might exhibit those inclinations, and Chernow argues that it sounds a lot like the current occupant of the Oval Office:

"When a man unprincipled in private life[,] desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper . . . despotic in his ordinary demeanour — known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty — when such a man is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity — to join in the cry of danger to liberty — to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government & bringing it under suspicion — to flatter and fall in with all the non sense of the zealots of the day — It may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may 'ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.'"

Remainder of article:

https://www.npr.org/2019/11/18/779938...

Discussion Question:

1. Read the article and discuss any points you would like regarding current politics and the importance of the founders' words and concerns. Cite the article - lines - quotes - etc. so that we can understand readily your post. Remember to be civil and respectful.

Mississippi Business Journal

BEN WILLIAMS — You only thought no man was above the law

Note: These articles do not represent the views or viewpoints of the HBC. We are adding pertinent articles for the basis of debate, interaction and discussion.

Link: https://msbusiness.com/2019/11/ben-wi...

Discussion Question:

1. Do you agree with Ben Williams' interpretation of the powers of the presidency and what the founding fathers stated in Federalist. No 69? Why or why not? Remember to be civil and respectful of other members' points of view if different than your own.

BEN WILLIAMS — You only thought no man was above the law

Note: These articles do not represent the views or viewpoints of the HBC. We are adding pertinent articles for the basis of debate, interaction and discussion.

Link: https://msbusiness.com/2019/11/ben-wi...

Discussion Question:

1. Do you agree with Ben Williams' interpretation of the powers of the presidency and what the founding fathers stated in Federalist. No 69? Why or why not? Remember to be civil and respectful of other members' points of view if different than your own.

The Biggest Question Facing Voters in 2020 by Elliot Williams - Article and Videos

The notion that the president's power has guard rails is not new; in 1788, Alexander Hamilton took pains in Federalist No. 69 to lay out all the reasons why the president is not, in fact, a king with absolute power over government.

Don't be fooled; the 2020 election isn't about the economy, or health care, or whether America is finally willing to stop holding female candidates to double standards about how "likable" they are.

(Well, it's maybe about that last one, but that's another story.)

To some extent, the election isn't even a referendum on President Donald Trump's performance as a leader. The key question voters are confronting in 2020 is simpler: Do rules matter?

The President's conduct reinforces for the public the false idea that rules and laws simply do not matter when you disagree with them (profoundly ironic from an individual who once branded himself the "law and order candidate"). Rules exist to provide a basic sense of order in society, and reasonable minds can differ about what a common set of laws and rules ought to be. For instance, any family that has agreed to modify one of the rules governing the board game Monopoly on game night can attest that sometimes it is OK for rules to be fluid. But the game works only when all parties recognize its basic framework. For the game to work, one Monopoly player cannot unilaterally decide to start playing three card monte and then attack the rules of Monopoly as "rigged" and a "witch hunt."

Link to the Remainder of the Article:

https://www.cnn.com/2019/11/05/opinio...

Discussion Questions:

What are your thoughts about this article and its basic premise? Feel free to cite quotes from this article and Federalist. No. 69 to support your basic premise or ideas. Do you agree with the article? Why or why not?

Source: CNN Opinion

The notion that the president's power has guard rails is not new; in 1788, Alexander Hamilton took pains in Federalist No. 69 to lay out all the reasons why the president is not, in fact, a king with absolute power over government.

Don't be fooled; the 2020 election isn't about the economy, or health care, or whether America is finally willing to stop holding female candidates to double standards about how "likable" they are.

(Well, it's maybe about that last one, but that's another story.)

To some extent, the election isn't even a referendum on President Donald Trump's performance as a leader. The key question voters are confronting in 2020 is simpler: Do rules matter?

The President's conduct reinforces for the public the false idea that rules and laws simply do not matter when you disagree with them (profoundly ironic from an individual who once branded himself the "law and order candidate"). Rules exist to provide a basic sense of order in society, and reasonable minds can differ about what a common set of laws and rules ought to be. For instance, any family that has agreed to modify one of the rules governing the board game Monopoly on game night can attest that sometimes it is OK for rules to be fluid. But the game works only when all parties recognize its basic framework. For the game to work, one Monopoly player cannot unilaterally decide to start playing three card monte and then attack the rules of Monopoly as "rigged" and a "witch hunt."

Link to the Remainder of the Article:

https://www.cnn.com/2019/11/05/opinio...

Discussion Questions:

What are your thoughts about this article and its basic premise? Feel free to cite quotes from this article and Federalist. No. 69 to support your basic premise or ideas. Do you agree with the article? Why or why not?

Source: CNN Opinion

message 9:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 25, 2019 06:11PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

The Egalitarian - Student Voice - Virginia Grant

"Sometimes, and it is happening with increasing frequency, I find that the average citizen possesses a profound lack of understanding regarding the most basic precepts of American democracy. Part of the blame rests in our education system. For generations we have passed on a revisionist history that, although false, is more widely accepted than the truth.

A standard textbook teaches that in Colonial and Early American times only white men of property could vote. While false students must learn this as fact to past the course and pass the course to earn a degree.

Acceptance of lies as acceptable alternative facts is the path to advancement. This perversion has led to our current state of free fall corruption.

I have heard endless debates regarding the intent of one passage or another in the Constitution. In most cases those issues could be easily resolved by reading the Federalist Papers. The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788 and published in newspapers under the name “Publius. “The intent was to explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail with the aim of convincing New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution. They have since been compiled in several editions, one of which is available on the Congress.gov website, another in the Gutenberg.org site. They are not hard to find, any Google or Bing search will turn up a plethora of sites that offer full text versions of the Federalist Papers.

Now if anyone wants to hear the facts about the powers and responsibilities of the Presidency, before they go spouting impassioned opinions here is what Madison had to say in Federalist No. 69 as he compares the American President to the King of England.

The President of the United States would be an officer elected by the people for four years; the king of Great Britain is a perpetual and hereditary prince. The one would be amenable to personal punishment and disgrace; the person of the other is sacred and inviolable. The one would have a qualified negative upon the acts of the legislative body; the other has an absolute negative. The one would have a right to command the military and naval forces of the nation; the other, in addition to this right, possesses that of declaring war, and of raising and regulating fleets and armies by his own authority. The one would have a concurrent power with a branch of the legislature in the formation of treaties; the other is the sole possessor of the power of making treaties. The one would have a like concurrent authority in appointing to offices; the other is the sole author of all appointments. The one can confer no privileges whatever; the other can make denizens of aliens, noblemen of commoners; can erect corporations with all the rights incident to corporate bodies. The one can prescribe no rules concerning the commerce or currency of the nation; the other is in several respects the arbiter of commerce, and in this capacity can establish markets and fairs, can regulate weights and measures, can lay embargoes for a limited time, can coin money, can authorize or prohibit the circulation of foreign coin. The one has no particle of spiritual jurisdiction; the other is the supreme head and governor of the national church! What answer shall we give to those who would persuade us that things so unlike resemble each other? The same that ought to be given to those who tell us that a government, the whole power of which would be in the hands of the elective and periodical servants of the people, is an aristocracy, a monarchy, and a despotism.

Now this makes it clear that the President is not above the law.

That he does not have the right to unilaterally declare war. That he must work with the Legislature to make treaties and appointments to offices.

That he can make no rules concerning commerce or currency and does not have the King’s ability to lay embargos, coin money or establish markets.

It explicitly states that the President “has no particle of spiritual jurisdiction.” This was Madison’s summary of the powers of a periodical and elective servant of the people.

If we are to remain true to the spirit of the Constitution, and not just interpret its words to suit our intent, we must take the time to learn the intent behind its construction. It is not hard to find, nor is it an exceptionally long read. Unfortunately most of us are better informed of the governance issues in Westeros than in the foundations of the United States Government.

Source: The Egalitarian

Discussion Questions:

What are your thoughts about the article and the points highlighted which reflect the ideas cited in Federalist. No 69? Do you agree or disagree? Why or why not?

"Sometimes, and it is happening with increasing frequency, I find that the average citizen possesses a profound lack of understanding regarding the most basic precepts of American democracy. Part of the blame rests in our education system. For generations we have passed on a revisionist history that, although false, is more widely accepted than the truth.

A standard textbook teaches that in Colonial and Early American times only white men of property could vote. While false students must learn this as fact to past the course and pass the course to earn a degree.

Acceptance of lies as acceptable alternative facts is the path to advancement. This perversion has led to our current state of free fall corruption.

I have heard endless debates regarding the intent of one passage or another in the Constitution. In most cases those issues could be easily resolved by reading the Federalist Papers. The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788 and published in newspapers under the name “Publius. “The intent was to explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail with the aim of convincing New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution. They have since been compiled in several editions, one of which is available on the Congress.gov website, another in the Gutenberg.org site. They are not hard to find, any Google or Bing search will turn up a plethora of sites that offer full text versions of the Federalist Papers.

Now if anyone wants to hear the facts about the powers and responsibilities of the Presidency, before they go spouting impassioned opinions here is what Madison had to say in Federalist No. 69 as he compares the American President to the King of England.

The President of the United States would be an officer elected by the people for four years; the king of Great Britain is a perpetual and hereditary prince. The one would be amenable to personal punishment and disgrace; the person of the other is sacred and inviolable. The one would have a qualified negative upon the acts of the legislative body; the other has an absolute negative. The one would have a right to command the military and naval forces of the nation; the other, in addition to this right, possesses that of declaring war, and of raising and regulating fleets and armies by his own authority. The one would have a concurrent power with a branch of the legislature in the formation of treaties; the other is the sole possessor of the power of making treaties. The one would have a like concurrent authority in appointing to offices; the other is the sole author of all appointments. The one can confer no privileges whatever; the other can make denizens of aliens, noblemen of commoners; can erect corporations with all the rights incident to corporate bodies. The one can prescribe no rules concerning the commerce or currency of the nation; the other is in several respects the arbiter of commerce, and in this capacity can establish markets and fairs, can regulate weights and measures, can lay embargoes for a limited time, can coin money, can authorize or prohibit the circulation of foreign coin. The one has no particle of spiritual jurisdiction; the other is the supreme head and governor of the national church! What answer shall we give to those who would persuade us that things so unlike resemble each other? The same that ought to be given to those who tell us that a government, the whole power of which would be in the hands of the elective and periodical servants of the people, is an aristocracy, a monarchy, and a despotism.

Now this makes it clear that the President is not above the law.

That he does not have the right to unilaterally declare war. That he must work with the Legislature to make treaties and appointments to offices.

That he can make no rules concerning commerce or currency and does not have the King’s ability to lay embargos, coin money or establish markets.

It explicitly states that the President “has no particle of spiritual jurisdiction.” This was Madison’s summary of the powers of a periodical and elective servant of the people.

If we are to remain true to the spirit of the Constitution, and not just interpret its words to suit our intent, we must take the time to learn the intent behind its construction. It is not hard to find, nor is it an exceptionally long read. Unfortunately most of us are better informed of the governance issues in Westeros than in the foundations of the United States Government.

Source: The Egalitarian

Discussion Questions:

What are your thoughts about the article and the points highlighted which reflect the ideas cited in Federalist. No 69? Do you agree or disagree? Why or why not?

message 10:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 25, 2019 06:16PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Trump's impeachment defense boils down to this: Treat me like a king

If he can't be indicted, and if he can dictate his own terms to Congress - as the White House counsel suggests - then the president is saying that he's something other than a president

Link to remainder of article:

https://www.washingtonpost.com

Source: The Washington Post

Discussion Questions:

1. What are your thoughts about the hypothesis of the article and its basic premise? Do you agree or disagree? Why or why not?

How does the article cite or reflect upon the ideas and writings of our founding fathers in Federalist. No 69? Try to be as specific as you can. Remember to be respectful and civil to those other members who might disagree with your viewpoint and vice versa.

If he can't be indicted, and if he can dictate his own terms to Congress - as the White House counsel suggests - then the president is saying that he's something other than a president

Link to remainder of article:

https://www.washingtonpost.com

Source: The Washington Post

Discussion Questions:

1. What are your thoughts about the hypothesis of the article and its basic premise? Do you agree or disagree? Why or why not?

How does the article cite or reflect upon the ideas and writings of our founding fathers in Federalist. No 69? Try to be as specific as you can. Remember to be respectful and civil to those other members who might disagree with your viewpoint and vice versa.

Presidents aren't kings. Someone should tell Trump's legal team

If he says he's above the law. Congress has to rein him in.

Link to article: https://www.washingtonpost.com

Discussion Questions:

1. Reflect upon Federalist. No 69 and what Hamilton has to say about the Real Character of the Executive. What points does this article make which reflect upon this essay and what our Founding Fathers had to say? Try to be specific. Remember to be respectful and civil to those members who might disagree with your viewpoint and vice versa.

Source: The Washington Post

If he says he's above the law. Congress has to rein him in.

Link to article: https://www.washingtonpost.com

Discussion Questions:

1. Reflect upon Federalist. No 69 and what Hamilton has to say about the Real Character of the Executive. What points does this article make which reflect upon this essay and what our Founding Fathers had to say? Try to be specific. Remember to be respectful and civil to those members who might disagree with your viewpoint and vice versa.

Source: The Washington Post

Please feel free to jump into the conversation any time.

I will continue to discuss this paper for a bit and then we will move on going to back to where we left off.

I will continue to discuss this paper for a bit and then we will move on going to back to where we left off.

Let us begin with the text of Federalist Paper 69:

Federalist № 69

The Real Character of the Executive

To the People of the State of New York:

I proceed now to trace the real characters of the proposed Executive, as they are marked out in the plan of the convention. This will serve to place in a strong light the unfairness of the representations which have been made in regard to it. ¶1

The first thing which strikes our attention is, that the executive authority, with few exceptions, is to be vested in a single magistrate. This will scarcely, however, be considered as a point upon which any comparison can be grounded; for if, in this particular, there be a resemblance to the king of Great Britain, there is not less a resemblance to the Grand Seignior, to the khan of Tartary, to the Man of the Seven Mountains, or to the governor of New York. ¶2

That magistrate is to be elected for four years; and is to be re-eligible as often as the people of the United States shall think him worthy of their confidence. In these circumstances there is a total dissimilitude between him and a king of Great Britain, who is an hereditary monarch, possessing the crown as a patrimony descendible to his heirs forever; but there is a close analogy between him and a governor of New York, who is elected for three years, and is re-eligible without limitation or intermission. If we consider how much less time would be requisite for establishing a dangerous influence in a single State, than for establishing a like influence throughout the United States, we must conclude that a duration of four years for the Chief Magistrate of the Union is a degree of permanency far less to be dreaded in that office, than a duration of three years for a corresponding office in a single State. ¶3

The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law. The person of the king of Great Britain is sacred and inviolable; there is no constitutional tribunal to which he is amenable; no punishment to which he can be subjected without involving the crisis of a national revolution. In this delicate and important circumstance of personal responsibility, the President of Confederated America would stand upon no better ground than a governor of New York, and upon worse ground than the governors of Maryland and Delaware. ¶4

Federalist № 69

The Real Character of the Executive

To the People of the State of New York:

I proceed now to trace the real characters of the proposed Executive, as they are marked out in the plan of the convention. This will serve to place in a strong light the unfairness of the representations which have been made in regard to it. ¶1

The first thing which strikes our attention is, that the executive authority, with few exceptions, is to be vested in a single magistrate. This will scarcely, however, be considered as a point upon which any comparison can be grounded; for if, in this particular, there be a resemblance to the king of Great Britain, there is not less a resemblance to the Grand Seignior, to the khan of Tartary, to the Man of the Seven Mountains, or to the governor of New York. ¶2

That magistrate is to be elected for four years; and is to be re-eligible as often as the people of the United States shall think him worthy of their confidence. In these circumstances there is a total dissimilitude between him and a king of Great Britain, who is an hereditary monarch, possessing the crown as a patrimony descendible to his heirs forever; but there is a close analogy between him and a governor of New York, who is elected for three years, and is re-eligible without limitation or intermission. If we consider how much less time would be requisite for establishing a dangerous influence in a single State, than for establishing a like influence throughout the United States, we must conclude that a duration of four years for the Chief Magistrate of the Union is a degree of permanency far less to be dreaded in that office, than a duration of three years for a corresponding office in a single State. ¶3

The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law. The person of the king of Great Britain is sacred and inviolable; there is no constitutional tribunal to which he is amenable; no punishment to which he can be subjected without involving the crisis of a national revolution. In this delicate and important circumstance of personal responsibility, the President of Confederated America would stand upon no better ground than a governor of New York, and upon worse ground than the governors of Maryland and Delaware. ¶4

message 14:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 01, 2020 10:34AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Let us focus on the first four paragraphs:

"Federalist No. 69, Alexander Hamilton sought to explain the nature of the executive branch in order to address fears that the President would function as an elected monarch, the primary concern of Anti-Federalists.

The memory of British oppression was fresh in the mind of Anti-Federalists, and they were not ready to accept any new government that would resemble the English form of government.

Specifically, Hamilton "explained that the president's authority 'would be nominally the same with that of the King of Great Britain, but in substance much inferior to it.

It would amount to nothing more than the supreme command and direction of the military and naval forces, as first general and admiral of the confederacy.

Hamilton seeks to counter claims that the president would be an “elective monarch” as the anti-federalists claimed.

Hamilton points to the fact that the president is elected, whereas the king of England inherits his position. The president furthermore has only a qualified negative on legislative acts—i.e. his veto can be overturned—whereas the king has an absolute negative.

Hamilton furthermore suggests that, in many respects, the president would have less powers over his constituents than the governor of New York has over his.

Hamilton structures his argument around a three-way comparison of the office of the presidency under the proposed constitution, the king of England, and the governor of New York. Hamilton’s chief concern is to counter claims that the president would have powers commensurate to the English monarch against whom Americans fought a war. He does this in a very specific and methodical way, taking a variety of issues and comparing the powers of the president and the king.

In order to make the argument more relevant to the people of New York, who Hamilton is addressing, he introduces a comparison between the president and the governor of New York as well. Surely, the people of New York would not claim that the president under the proposed constitution is an elected monarch if his powers are roughly commensurate to their own governor.

Hamilton structures his argument around a three-way comparison of the office of the presidency under the proposed constitution, the king of England, and the governor of New York. Hamilton’s chief concern is to counter claims that the president would have powers commensurate to the English monarch against whom Americans fought a war. He does this in a very specific and methodical way, taking a variety of issues and comparing the powers of the president and the king.

In order to make the argument more relevant to the people of New York, who Hamilton is addressing, he introduces a comparison between the president and the governor of New York as well. Surely, the people of New York would not claim that the president under the proposed constitution is an elected monarch if his powers are roughly commensurate to their own governor.

The president would be elected for a term of four years; he would be eligible for re-election. He would not have the life tenure of an hereditary monarch. The president would be liable to impeachment, trial, and removal from office upon being found guilty of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors. He would be accountable at all times to the country at large.

In addition, the president would have the power to pardon all offenders except those found guilty in an impeachment trial.

But since a president was to be elected every four years, he could not possibly become a "perpetual and hereditary prince" like the despised and "tyrannical" King George III.

It appears that this line is most appropriate to what we learned about impeachment this year:

The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.

I think the key word is "afterwards" that he would be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of the law. So Trump - 'unless impeached" will not be prosecuted or punished for anything that he does or might do until out of office either by being impeached or by not being re-elected.

I also thought it interesting that Hamilton called out that some governors are more "equal than others". That the power of the New York Governor stood on a better ground in terms of power, personal responsibility, than the governors of Maryland and Delaware. I also thought it was interesting phrasing to talk about the President as not only the President of the United States but also the President of the Confederated America!

According to Constituting America and Professor Knipprath - "He (Hamilton) chooses the latter for several reasons. First, the essays of Publius are written during the pendency of the New York and Virginia ratifying conventions and were obviously intended in the first instance to influence those closely-fought skirmishes.

Second, Hamilton was deeply involved in state politics as a member of the downstate faction that favored both the Constitution and, later, the Federalist Party. Though it is hard to believe today, New York City politically was, in many ways, a Tory town. It was a hotbed of Loyalist sentiment during the Revolutionary War, so much so that the British made it their headquarters. Hamilton was intimately familiar with the operation of his state’s government and, given the emerging significance of the city and state, would find New York’s system more important than others

Third, the governor of New York was a rather strong chief executive compared to the state governors at the time. Comparing the president’s powers favorably to those of a republican American state executive would resonate particularly well with the persuadable delegates by avoiding charges that comparing the prerogatives of the president to those of the British monarch was irrelevant to the cause, as no American king was to be crowned.

But there is one more reason. The governor of New York, George Clinton, was the presiding officer at the convention and a staunch Antifederalist. He was also a member of the upstate Albany faction politically opposed to Hamilton. Clinton is the likely author of potent attacks on the Constitution in “Letters of Cato.” Many historians believe that it was the publication of some of those letters that induced the Constitution’s supporters to organize the effort that became The Federalist. The executive was one of Cato’s particular concerns. In an essay published four months before Federalist 69, Cato labeled the president the “generalissimo of the nation,” assailed the scope of the president’s powers, compared those powers alarmingly with those of the king of Great Britain (especially the war power), and warned, “You must, however, my countrymen, beware that the advocates of this new system do not deceive you by a fallacious resemblance between it and your own state government [New York]….If you examine, you…will be convinced that this government is no more like a true picture of your own than an Angel of Darkness resembles an Angel of Light.” Hamilton had no choice but to respond.

The result is a brief comparative overview, the particulars of which do not matter much today, as the king’s prerogatives, already circumscribed then, are virtually non-existent now. The essay does provide an introduction to various powers of the president, most of which are in Article II of the Constitution. Hamilton will delve into greater detail of various of them over the course of Federalist 73 to 77.

What is significant for us is the dog that does not bark, the constitutional clauses that are not mentioned by Publius. Not long after the Constitution was approved, Hamilton used the occasion of Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation in 1793 to advance a broad theory of implied executive powers. His position, vigorously challenged by Madison during the Pacificus-Helvidius debates, was that the president has all powers that are not denied to him under the Constitution either expressly or by unambiguous grant to another branch. That approach has been used by subsequent presidents to fuel the expansion of executive power.

Article II is rather short, and the president’s powers few and specific. Beyond that, the boundaries are vague. It was broadly understood that George Washington would be the first president. The general recognition of his propriety and incorruptibility meant that he would have discretion to define the boundaries of the office. Indeed, Washington was expected to do so, and he was well aware of that responsibility. In addition to the oath of office, there are three clauses whose text suggests room for discretion. Those three, the executive power clause, the commander-in-chief clause, and the clause that the president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” have proved to be generous reservoirs of necessary implied executive powers.

Publius spends little time on the commander-in-chief clause, and essentially none on the others. He portrays the role of the president as if he would be confined to leading the troops in military engagements.

The executive power clause is the principal source for the president’s implied or inherent powers, those that the president’s detractors would disparagingly call royal or prerogative powers. The textual significance is that, while Article I says that, “All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress …,” Article II declares that, “The executive power shall be vested in a President …”[italics added]. That affirmative grant to the president has to mean something, and –unlike Article I regarding Congress–it has to mean more than the powers mentioned later in the text. The question ever since has been, “Just what does it mean?” Presidents have massaged that ambiguity and the flexibility of the other elastic clauses mentioned to act unilaterally, as necessity demands, usually in military affairs, foreign relations, and national security matters. Executive unilateralism came under particular scrutiny by Congress, the courts, the academy, and the media during the Bush(43) administration, though interest in that topic has slackened since the election of 2008–perhaps not coincidentally.

Not surprisingly, as advocate for the Constitution’s adoption, Hamilton does not spend time defending, or even recognizing, the theory of implied executive powers that he embraced soon thereafter. The enumeration of specific limited presidential powers and Hamilton’s soothing interpretations in Federalist 69 do not give due credit to the possible sweep of the executive office. His next essay presents a more forthright defense of the need for an energetic executive." - (the above is from Constituting America and a blog written by Joerg Knipprath, Professor of Law at Southwestern Law School)

Discussion Topic:

What are your thoughts on the above (Paragraphs 1 - 4) and on Professor Knipprath's premise?

Sources: Wikipedia, Grade Saver, Cliffnotes, Constituting America, and The Powers of the President, From the New York Packet (Hamilton) – Guest Blogger: Joerg Knipprath, Professor of Law at Southwestern Law School

The above completes the explanation of paragraphs 1 - 4 of 69

"Federalist No. 69, Alexander Hamilton sought to explain the nature of the executive branch in order to address fears that the President would function as an elected monarch, the primary concern of Anti-Federalists.

The memory of British oppression was fresh in the mind of Anti-Federalists, and they were not ready to accept any new government that would resemble the English form of government.

Specifically, Hamilton "explained that the president's authority 'would be nominally the same with that of the King of Great Britain, but in substance much inferior to it.

It would amount to nothing more than the supreme command and direction of the military and naval forces, as first general and admiral of the confederacy.

Hamilton seeks to counter claims that the president would be an “elective monarch” as the anti-federalists claimed.

Hamilton points to the fact that the president is elected, whereas the king of England inherits his position. The president furthermore has only a qualified negative on legislative acts—i.e. his veto can be overturned—whereas the king has an absolute negative.

Hamilton furthermore suggests that, in many respects, the president would have less powers over his constituents than the governor of New York has over his.

Hamilton structures his argument around a three-way comparison of the office of the presidency under the proposed constitution, the king of England, and the governor of New York. Hamilton’s chief concern is to counter claims that the president would have powers commensurate to the English monarch against whom Americans fought a war. He does this in a very specific and methodical way, taking a variety of issues and comparing the powers of the president and the king.

In order to make the argument more relevant to the people of New York, who Hamilton is addressing, he introduces a comparison between the president and the governor of New York as well. Surely, the people of New York would not claim that the president under the proposed constitution is an elected monarch if his powers are roughly commensurate to their own governor.

Hamilton structures his argument around a three-way comparison of the office of the presidency under the proposed constitution, the king of England, and the governor of New York. Hamilton’s chief concern is to counter claims that the president would have powers commensurate to the English monarch against whom Americans fought a war. He does this in a very specific and methodical way, taking a variety of issues and comparing the powers of the president and the king.

In order to make the argument more relevant to the people of New York, who Hamilton is addressing, he introduces a comparison between the president and the governor of New York as well. Surely, the people of New York would not claim that the president under the proposed constitution is an elected monarch if his powers are roughly commensurate to their own governor.

The president would be elected for a term of four years; he would be eligible for re-election. He would not have the life tenure of an hereditary monarch. The president would be liable to impeachment, trial, and removal from office upon being found guilty of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors. He would be accountable at all times to the country at large.

In addition, the president would have the power to pardon all offenders except those found guilty in an impeachment trial.

But since a president was to be elected every four years, he could not possibly become a "perpetual and hereditary prince" like the despised and "tyrannical" King George III.

It appears that this line is most appropriate to what we learned about impeachment this year:

The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.

I think the key word is "afterwards" that he would be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of the law. So Trump - 'unless impeached" will not be prosecuted or punished for anything that he does or might do until out of office either by being impeached or by not being re-elected.

I also thought it interesting that Hamilton called out that some governors are more "equal than others". That the power of the New York Governor stood on a better ground in terms of power, personal responsibility, than the governors of Maryland and Delaware. I also thought it was interesting phrasing to talk about the President as not only the President of the United States but also the President of the Confederated America!

According to Constituting America and Professor Knipprath - "He (Hamilton) chooses the latter for several reasons. First, the essays of Publius are written during the pendency of the New York and Virginia ratifying conventions and were obviously intended in the first instance to influence those closely-fought skirmishes.

Second, Hamilton was deeply involved in state politics as a member of the downstate faction that favored both the Constitution and, later, the Federalist Party. Though it is hard to believe today, New York City politically was, in many ways, a Tory town. It was a hotbed of Loyalist sentiment during the Revolutionary War, so much so that the British made it their headquarters. Hamilton was intimately familiar with the operation of his state’s government and, given the emerging significance of the city and state, would find New York’s system more important than others

Third, the governor of New York was a rather strong chief executive compared to the state governors at the time. Comparing the president’s powers favorably to those of a republican American state executive would resonate particularly well with the persuadable delegates by avoiding charges that comparing the prerogatives of the president to those of the British monarch was irrelevant to the cause, as no American king was to be crowned.

But there is one more reason. The governor of New York, George Clinton, was the presiding officer at the convention and a staunch Antifederalist. He was also a member of the upstate Albany faction politically opposed to Hamilton. Clinton is the likely author of potent attacks on the Constitution in “Letters of Cato.” Many historians believe that it was the publication of some of those letters that induced the Constitution’s supporters to organize the effort that became The Federalist. The executive was one of Cato’s particular concerns. In an essay published four months before Federalist 69, Cato labeled the president the “generalissimo of the nation,” assailed the scope of the president’s powers, compared those powers alarmingly with those of the king of Great Britain (especially the war power), and warned, “You must, however, my countrymen, beware that the advocates of this new system do not deceive you by a fallacious resemblance between it and your own state government [New York]….If you examine, you…will be convinced that this government is no more like a true picture of your own than an Angel of Darkness resembles an Angel of Light.” Hamilton had no choice but to respond.

The result is a brief comparative overview, the particulars of which do not matter much today, as the king’s prerogatives, already circumscribed then, are virtually non-existent now. The essay does provide an introduction to various powers of the president, most of which are in Article II of the Constitution. Hamilton will delve into greater detail of various of them over the course of Federalist 73 to 77.

What is significant for us is the dog that does not bark, the constitutional clauses that are not mentioned by Publius. Not long after the Constitution was approved, Hamilton used the occasion of Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation in 1793 to advance a broad theory of implied executive powers. His position, vigorously challenged by Madison during the Pacificus-Helvidius debates, was that the president has all powers that are not denied to him under the Constitution either expressly or by unambiguous grant to another branch. That approach has been used by subsequent presidents to fuel the expansion of executive power.

Article II is rather short, and the president’s powers few and specific. Beyond that, the boundaries are vague. It was broadly understood that George Washington would be the first president. The general recognition of his propriety and incorruptibility meant that he would have discretion to define the boundaries of the office. Indeed, Washington was expected to do so, and he was well aware of that responsibility. In addition to the oath of office, there are three clauses whose text suggests room for discretion. Those three, the executive power clause, the commander-in-chief clause, and the clause that the president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” have proved to be generous reservoirs of necessary implied executive powers.

Publius spends little time on the commander-in-chief clause, and essentially none on the others. He portrays the role of the president as if he would be confined to leading the troops in military engagements.

The executive power clause is the principal source for the president’s implied or inherent powers, those that the president’s detractors would disparagingly call royal or prerogative powers. The textual significance is that, while Article I says that, “All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress …,” Article II declares that, “The executive power shall be vested in a President …”[italics added]. That affirmative grant to the president has to mean something, and –unlike Article I regarding Congress–it has to mean more than the powers mentioned later in the text. The question ever since has been, “Just what does it mean?” Presidents have massaged that ambiguity and the flexibility of the other elastic clauses mentioned to act unilaterally, as necessity demands, usually in military affairs, foreign relations, and national security matters. Executive unilateralism came under particular scrutiny by Congress, the courts, the academy, and the media during the Bush(43) administration, though interest in that topic has slackened since the election of 2008–perhaps not coincidentally.

Not surprisingly, as advocate for the Constitution’s adoption, Hamilton does not spend time defending, or even recognizing, the theory of implied executive powers that he embraced soon thereafter. The enumeration of specific limited presidential powers and Hamilton’s soothing interpretations in Federalist 69 do not give due credit to the possible sweep of the executive office. His next essay presents a more forthright defense of the need for an energetic executive." - (the above is from Constituting America and a blog written by Joerg Knipprath, Professor of Law at Southwestern Law School)

Discussion Topic:

What are your thoughts on the above (Paragraphs 1 - 4) and on Professor Knipprath's premise?

Sources: Wikipedia, Grade Saver, Cliffnotes, Constituting America, and The Powers of the President, From the New York Packet (Hamilton) – Guest Blogger: Joerg Knipprath, Professor of Law at Southwestern Law School

The above completes the explanation of paragraphs 1 - 4 of 69

message 15:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 01, 2020 06:07PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Here is Article II of the Constitution which was referred to in the essay by Professor Knipprath in the comment box above: - Section One

ARTICLE II

Executive Branch

Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788.

Portions of Article II, Section 1, were changed by the 12th Amendment and the 25th Amendment

Section 1

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. (This sentence is called the vesting clause)

He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector. (These clauses discuss the Electoral College)

The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two Persons, of whom one at least shall not be an Inhabitant of the same State with themselves. And they shall make a List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each; which List they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the Seat of the Government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted. The Person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a Majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed; and if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately chose by Ballot one of them for President; and if no Person have a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in like Manner chose the President. But in chosing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representation from each State having one Vote; A quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two thirds of the States, and a Majority of all the States shall be necessary to a Choice. In every Case, after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal Votes, the Senate shall chose from them by Ballot the Vice President. (The 12th amendment superseded this clause; after the election of 1800 in which Thomas Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr, received identical votes and both claimed the office. After many votes the House of Representatives chose Thomas Jefferson and soon hereafter the amendment was speedily approved.)

The Congress may determine the Time of chosing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.

In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected. (The 25th amendment superseded this clause; regarding presidential disability, vacancy of the office, and methods of succession.)

The President shall, at stated Times, receive for his Services, a Compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during the Period for which he shall have been elected, and he shall not receive within that Period any other Emolument from the United States, or any of them.

Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:--"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

Source: The US Constitution

ARTICLE II

Executive Branch

Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788.

Portions of Article II, Section 1, were changed by the 12th Amendment and the 25th Amendment

Section 1

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. (This sentence is called the vesting clause)

He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector. (These clauses discuss the Electoral College)

The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two Persons, of whom one at least shall not be an Inhabitant of the same State with themselves. And they shall make a List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each; which List they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the Seat of the Government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted. The Person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a Majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed; and if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately chose by Ballot one of them for President; and if no Person have a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in like Manner chose the President. But in chosing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representation from each State having one Vote; A quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two thirds of the States, and a Majority of all the States shall be necessary to a Choice. In every Case, after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal Votes, the Senate shall chose from them by Ballot the Vice President. (The 12th amendment superseded this clause; after the election of 1800 in which Thomas Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr, received identical votes and both claimed the office. After many votes the House of Representatives chose Thomas Jefferson and soon hereafter the amendment was speedily approved.)

The Congress may determine the Time of chosing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.

In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected. (The 25th amendment superseded this clause; regarding presidential disability, vacancy of the office, and methods of succession.)

The President shall, at stated Times, receive for his Services, a Compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during the Period for which he shall have been elected, and he shall not receive within that Period any other Emolument from the United States, or any of them.

Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:--"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

Source: The US Constitution

message 16:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 01, 2020 05:50PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

What is the Vesting Clause?

By Saikrishna B. Prakash and Christopher H. Schroeder

Mr. Prakash is the James Monroe Distinguished Professor of Law and Paul G. Mahoney Research Professor of Law at the University of Virginia School of Law.

Mr. Schroeder is the Charles S. Murphy Professor of Law and Public Policy Studies at Duke University Law School.