The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The British Are Coming

AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR

>

SPOTLIGHTED BOOK - THE BRITISH ARE COMING: THE WAR FOR AMERICA, LEXINGTON TO PRINCETON, 1775-1777 (THE REVOLUTION TRILOGY #1) - Week Four - June 1st - June 7th, 2020 - Chapters Seven/Eight/Nine (pages 182 - 240) Non Spoiler Thread

message 2:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

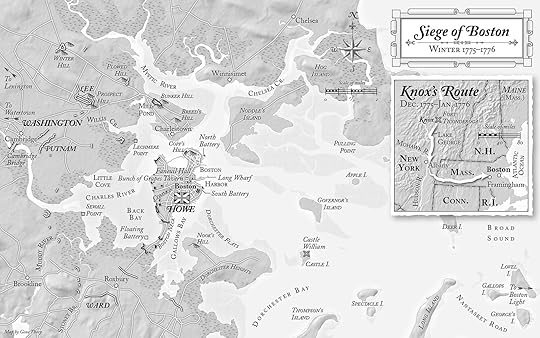

(last edited May 31, 2020 02:32PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Chapter Overviews and Summaries

Part One - continued:

7. THEY FOUGHT, BLED, AND DIED LIKE ENGLISHMEN

Norfolk, Virginia, December 1775

Our attention is turned to Norfolk, Viriginia - December, 1775.

8. THE PATHS OF GLORY

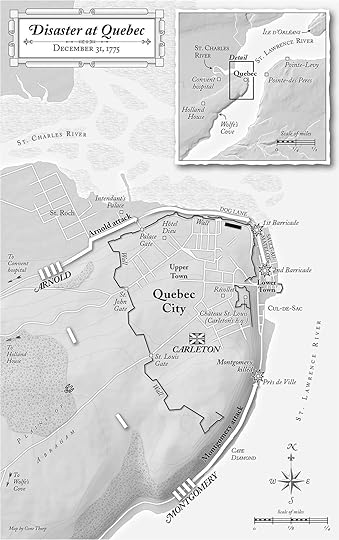

Quebec, December 3, 1775–January 1, 1776

Back to Quebec - December 3, 1775 - January 1, 1776.

Part Two

9. THE WAYS OF HEAVEN ARE DARK AND INTRICATE

Boston, January – February 1776

We turn our attention to Boston - January - February 1776.

Part One - continued:

7. THEY FOUGHT, BLED, AND DIED LIKE ENGLISHMEN

Norfolk, Virginia, December 1775

Our attention is turned to Norfolk, Viriginia - December, 1775.

8. THE PATHS OF GLORY

Quebec, December 3, 1775–January 1, 1776

Back to Quebec - December 3, 1775 - January 1, 1776.

Part Two

9. THE WAYS OF HEAVEN ARE DARK AND INTRICATE

Boston, January – February 1776

We turn our attention to Boston - January - February 1776.

message 3:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 05:33PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And so we begin:

7. They Fought, Bled, and Died Like Englishmen

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, DECEMBER 1775

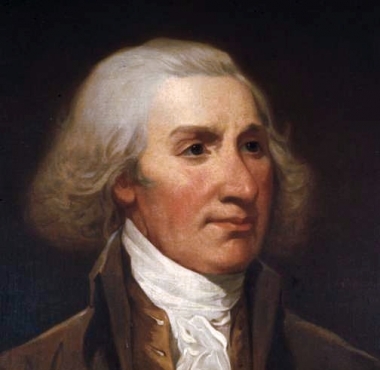

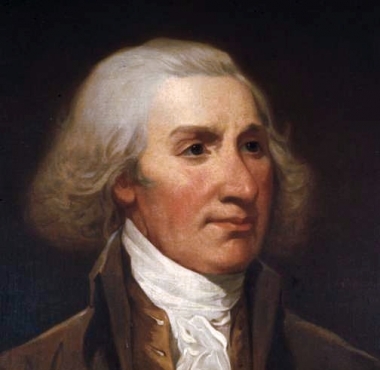

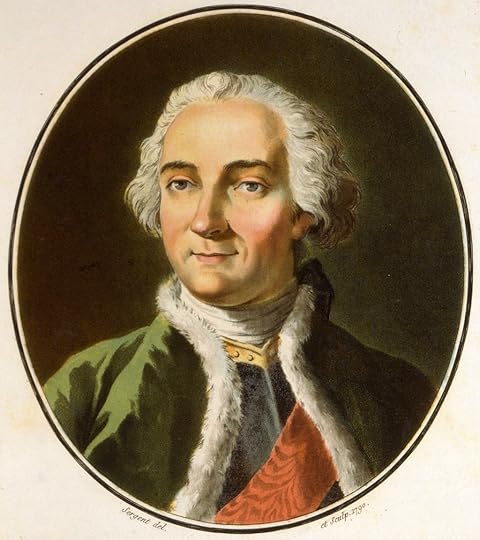

John Murray, the fourth earl of Dunmore and the royal governor of Virginia, had few rivals as the most detested British official in North America, particularly after he emancipated slaves owned by his rebel opponents. “That arch traitor to the rights of humanity, Lord Dunmore, should be instantly crushed,” Washington declared.

John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore and the royal governor of Virginia, had few rivals as the most detested British official in North America.

Now forty-five, he was a short, pugnacious Scot whose father had been arrested for treason in the 1745 Jacobite rising.

Young John subsequently chose to serve the English Crown as a soldier and was permitted to inherit the title after his father’s death in 1756. His estates in Perthshire provided £3,000 annually, but the fourth earl had accumulated both eleven children and expensive tastes.

He hired the eminent artist Joshua Reynolds to paint his portrait, in tam-o’-shanter and highland tartans; he also built a summer house with an enormous stone cupola shaped like a pineapple, later derided as “the most bizarre building in Scotland.”

Finding himself in financial straits, Dunmore sought to enlarge his fortune abroad.

Appointed governor of New York in 1770, he had no sooner arrived than London reassigned him to Virginia, a disappointment that sent him stumbling through Manhattan streets in a drunken rage, roaring, “Damn Virginia … I’d asked for New York.” One loyalist reflected, “Was there ever such a blockhead?”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 182). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

More:

http://www.thepeerage.com/info.htm

7. They Fought, Bled, and Died Like Englishmen

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, DECEMBER 1775

John Murray, the fourth earl of Dunmore and the royal governor of Virginia, had few rivals as the most detested British official in North America, particularly after he emancipated slaves owned by his rebel opponents. “That arch traitor to the rights of humanity, Lord Dunmore, should be instantly crushed,” Washington declared.

John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore and the royal governor of Virginia, had few rivals as the most detested British official in North America.

Now forty-five, he was a short, pugnacious Scot whose father had been arrested for treason in the 1745 Jacobite rising.

Young John subsequently chose to serve the English Crown as a soldier and was permitted to inherit the title after his father’s death in 1756. His estates in Perthshire provided £3,000 annually, but the fourth earl had accumulated both eleven children and expensive tastes.

He hired the eminent artist Joshua Reynolds to paint his portrait, in tam-o’-shanter and highland tartans; he also built a summer house with an enormous stone cupola shaped like a pineapple, later derided as “the most bizarre building in Scotland.”

Finding himself in financial straits, Dunmore sought to enlarge his fortune abroad.

Appointed governor of New York in 1770, he had no sooner arrived than London reassigned him to Virginia, a disappointment that sent him stumbling through Manhattan streets in a drunken rage, roaring, “Damn Virginia … I’d asked for New York.” One loyalist reflected, “Was there ever such a blockhead?”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 182). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

More:

http://www.thepeerage.com/info.htm

message 4:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 06:26PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, PC (1730 – 25 February 1809)

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, PC (1730 – 25 February 1809), generally known as Lord Dunmore, was a Scottish peer and colonial governor in the American colonies and The Bahamas. He was the last royal governor of Virginia.

Lord Dunmore was named governor of the Province of New York in 1770. He succeeded to the same position in the Colony of Virginia the following year, after the death of Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt. As Virginia's governor, Dunmore directed a series of campaigns against the trans-Appalachian Indians, known as Lord Dunmore's War. He is noted for issuing a 1775 document (Dunmore's Proclamation) offering freedom to any slave who fought for the Crown against the Patriots in Virginia. Dunmore fled to New York after the Burning of Norfolk in 1776, and later returned to Britain. He was Governor of the Bahama Islands from 1787 to 1796.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Mu...

Sources: Wikipedia, Encyclopedia of Virginia, PBS, Varsity Tutors, Internet Archive Wayback Machine, Appleton's

Flight of Lord Dunmore.

This 1907 color postcard commemorates the flight of John Murray, fourth earl of Dunmore and last royal governor of Virginia, from the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg to safety on the British man-of-war Fowey in June 1775. Dunmore essentially disarmed the colonists on April 20, 1775, by removing their gunpowder from the public magazine, and their strong reaction caused him to abandon permanently his Williamsburg post, seek Loyalist supporters in Hampton Roads, and ultimately sail to Great Britain in 1776.

The postcard was created for the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition in Norfolk.

Original Author: Ogden, artist, for the Jamestown Amusement & Vending Co., Inc.; American Colortype Co., printers

Created: 1907

Medium: Color halftone photomechanical postcard

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

More:

http://www.thepeerage.com/p10852.htm

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11941 (Lord Dunsmore's War)

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2p...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Applet...

https://www.varsitytutors.com/earlyam...

http://www.redhill.org/biography.html

Numerous Errors in Wilstach's "Tidewater Virginia" Challenge Criticism

J. Luther Kibler

The William and Mary Quarterly

Vol. 11, No. 2 (Apr., 1931), pp. 152-156 - Link: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1921010?...

by John Esten Cooke (no photo)

by John Esten Cooke (no photo)

by James Corbett David (no photo)

by James Corbett David (no photo)

by David Williamson (no photo)

by David Williamson (no photo)

by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo)

by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo)

by Ray Raphael (no photo)

by Ray Raphael (no photo)

by

by

Stephanie True Peters

Stephanie True Peters

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, PC (1730 – 25 February 1809), generally known as Lord Dunmore, was a Scottish peer and colonial governor in the American colonies and The Bahamas. He was the last royal governor of Virginia.

Lord Dunmore was named governor of the Province of New York in 1770. He succeeded to the same position in the Colony of Virginia the following year, after the death of Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt. As Virginia's governor, Dunmore directed a series of campaigns against the trans-Appalachian Indians, known as Lord Dunmore's War. He is noted for issuing a 1775 document (Dunmore's Proclamation) offering freedom to any slave who fought for the Crown against the Patriots in Virginia. Dunmore fled to New York after the Burning of Norfolk in 1776, and later returned to Britain. He was Governor of the Bahama Islands from 1787 to 1796.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Mu...

Sources: Wikipedia, Encyclopedia of Virginia, PBS, Varsity Tutors, Internet Archive Wayback Machine, Appleton's

Flight of Lord Dunmore.

This 1907 color postcard commemorates the flight of John Murray, fourth earl of Dunmore and last royal governor of Virginia, from the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg to safety on the British man-of-war Fowey in June 1775. Dunmore essentially disarmed the colonists on April 20, 1775, by removing their gunpowder from the public magazine, and their strong reaction caused him to abandon permanently his Williamsburg post, seek Loyalist supporters in Hampton Roads, and ultimately sail to Great Britain in 1776.

The postcard was created for the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition in Norfolk.

Original Author: Ogden, artist, for the Jamestown Amusement & Vending Co., Inc.; American Colortype Co., printers

Created: 1907

Medium: Color halftone photomechanical postcard

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

More:

http://www.thepeerage.com/p10852.htm

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11941 (Lord Dunsmore's War)

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2p...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i...

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Applet...

https://www.varsitytutors.com/earlyam...

http://www.redhill.org/biography.html

Numerous Errors in Wilstach's "Tidewater Virginia" Challenge Criticism

J. Luther Kibler

The William and Mary Quarterly

Vol. 11, No. 2 (Apr., 1931), pp. 152-156 - Link: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1921010?...

by John Esten Cooke (no photo)

by John Esten Cooke (no photo) by James Corbett David (no photo)

by James Corbett David (no photo) by David Williamson (no photo)

by David Williamson (no photo) by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo)

by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo) by Ray Raphael (no photo)

by Ray Raphael (no photo) by

by

Stephanie True Peters

Stephanie True Peters

message 5:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 05:03PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Did you know that pineapple were first grown in Scotland in 1731?

The Dunmore Pineapple, a folly ranked "as the most bizarre building in Scotland", stands in Dunmore Park, near Airth in Stirlingshire.

The walled garden at Dunmore Park

Dunmore Park, the ancestral home of the Earls of Dunmore, includes a large country mansion, Dunmore House, and grounds which contain, among other things, two large walled gardens.

Walled gardens were a necessity for any great house in a northern climate in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, as a high wall of stone or brick helped to shelter the garden from wind and frost, and could create a microclimate in which the ambient temperature could be raised several degrees above that of the surrounding landscape. This allowed the cultivation of fruits and vegetables, and also of ornamental plants, which could not otherwise survive that far north.

The larger of the two gardens covers about six acres, located on a gentle south-facing slope.

South-facing slopes are the ideal spot for walled gardens and for the cultivation of frost-sensitive plants. Along the north edge of the garden, the slope had probably originally been more steep. To allow both the upper and lower parts of the garden to be flat and level at different heights, it was necessary to bank up the earth on the higher northern side (away from the main house), behind a retaining wall about 16 feet (4.9 metres) high, and 3 ft 3 in (1.0 m) thick, which runs the entire length of the north side of the garden.[3]

Walled gardens sometimes included one hollow, or double, wall which contained furnaces, openings along the side facing the garden to allow heat to escape into the garden, and chimneys or flues to draw the smoke upwards. This particularly benefited fruit trees or grape vines that could, if grown within a few feet of a heated, south-facing wall, be grown even further north than the microclimate created by a walled garden would normally allow.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunmore...

Source: Wikipedia

More:

https://www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/t...

http://www.visitfalkirk.com/things-to...

https://www.scottish-places.info/feat...

http://gillonj.tripod.com/ascottishpi...

https://www.landmarktrust.org.uk/sear...

The Dunmore Pineapple, a folly ranked "as the most bizarre building in Scotland", stands in Dunmore Park, near Airth in Stirlingshire.

The walled garden at Dunmore Park

Dunmore Park, the ancestral home of the Earls of Dunmore, includes a large country mansion, Dunmore House, and grounds which contain, among other things, two large walled gardens.

Walled gardens were a necessity for any great house in a northern climate in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, as a high wall of stone or brick helped to shelter the garden from wind and frost, and could create a microclimate in which the ambient temperature could be raised several degrees above that of the surrounding landscape. This allowed the cultivation of fruits and vegetables, and also of ornamental plants, which could not otherwise survive that far north.

The larger of the two gardens covers about six acres, located on a gentle south-facing slope.

South-facing slopes are the ideal spot for walled gardens and for the cultivation of frost-sensitive plants. Along the north edge of the garden, the slope had probably originally been more steep. To allow both the upper and lower parts of the garden to be flat and level at different heights, it was necessary to bank up the earth on the higher northern side (away from the main house), behind a retaining wall about 16 feet (4.9 metres) high, and 3 ft 3 in (1.0 m) thick, which runs the entire length of the north side of the garden.[3]

Walled gardens sometimes included one hollow, or double, wall which contained furnaces, openings along the side facing the garden to allow heat to escape into the garden, and chimneys or flues to draw the smoke upwards. This particularly benefited fruit trees or grape vines that could, if grown within a few feet of a heated, south-facing wall, be grown even further north than the microclimate created by a walled garden would normally allow.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunmore...

Source: Wikipedia

More:

https://www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/t...

http://www.visitfalkirk.com/things-to...

https://www.scottish-places.info/feat...

http://gillonj.tripod.com/ascottishpi...

https://www.landmarktrust.org.uk/sear...

message 6:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 09:54PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Did Washington have a less than altruistic motive for helping to lead the Continental Army? Your thoughts.

The Ex-Slaves Who Fought with the British (check out article below by Christopher Klein) - While the patriots battled for freedom from Great Britain, upwards of 20,000 runaway slaves declared their own personal independence and fought on the side of the British

"Rebel leaders persuaded Virginians that rebellion “would enhance their opportunities and status,” the historian Alan Taylor later wrote, while also safeguarding political liberties threatened by an overbearing mother country.

Planter aristocrats—like the Washingtons, Lees, and Randolphs—helped lead the uprising, but only by common consent. Moreover, evangelical churches, notably the Baptists and Methodists, were promised elevated standing “by disestablishing the elitist Anglican Church” favored by Crown loyalists.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 183). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

More:

all by

all by

Alan Taylor

Alan Taylor

Source: Wikipedia

The Ex-Slaves Who Fought with the British (check out article below by Christopher Klein) - While the patriots battled for freedom from Great Britain, upwards of 20,000 runaway slaves declared their own personal independence and fought on the side of the British

"Rebel leaders persuaded Virginians that rebellion “would enhance their opportunities and status,” the historian Alan Taylor later wrote, while also safeguarding political liberties threatened by an overbearing mother country.

Planter aristocrats—like the Washingtons, Lees, and Randolphs—helped lead the uprising, but only by common consent. Moreover, evangelical churches, notably the Baptists and Methodists, were promised elevated standing “by disestablishing the elitist Anglican Church” favored by Crown loyalists.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 183). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

More:

all by

all by

Alan Taylor

Alan TaylorSource: Wikipedia

message 7:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 09:53PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Did you ever think that America started as a "fractious, disputatious, gun toting country with all the privates thinking they were generals" and with "very independent, courageous, pugnacious and fearless people" and that is why nothing has changed? Your thoughts?

The Virginia Gazette

"The colony became a leader in boycotting British goods and in summoning the Continental Congress to Philadelphia. Courts closed. Militia companies drilled. The Virginia Gazette published the names of loyalists considered hostile to liberty; some were ordered into western exile or to face the confiscation of their estates. “Lower-class men who did not own property saw the break from Britain as a chance to gain land and become slaveholders,” the historian Michael Kranish would write".

Note: All I could say was wow. Some broke from England so that they could own some land and have their own slaves! And then your name would be published in the newspaper if someone did not think you wanted to break from England! And you could be exiled! Tough times. Rough.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 183). Henry Holt and Co. Kindle Edition.

More:

by Michael Kranish (no photo)

by Michael Kranish (no photo)

Source: Wikipedia

The Virginia Gazette

"The colony became a leader in boycotting British goods and in summoning the Continental Congress to Philadelphia. Courts closed. Militia companies drilled. The Virginia Gazette published the names of loyalists considered hostile to liberty; some were ordered into western exile or to face the confiscation of their estates. “Lower-class men who did not own property saw the break from Britain as a chance to gain land and become slaveholders,” the historian Michael Kranish would write".

Note: All I could say was wow. Some broke from England so that they could own some land and have their own slaves! And then your name would be published in the newspaper if someone did not think you wanted to break from England! And you could be exiled! Tough times. Rough.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 183). Henry Holt and Co. Kindle Edition.

More:

by Michael Kranish (no photo)

by Michael Kranish (no photo)Source: Wikipedia

message 8:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 10:34PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

The Ex-Slaves Who Fought with the British by Christopher Klein

While the patriots battled for freedom from Great Britain, upwards of 20,000 runaway slaves declared their own personal independence and fought on the side of the British.

When American colonists took up arms in a battle for independence starting in 1775, that fight for freedom excluded an entire race of people—African-Americans. On November 12, 1775, General George Washington decreed in his orders that “neither negroes, boys unable to bear arms, nor old men” could enlist in the Continental Army.

Two days after the patriots’ military leader banned African-Americans from joining his ranks, however, black soldiers proved their mettle at the Battle of Kemp’s Landing along the Virginia coast. They captured an enemy commanding officer and proved pivotal in securing the victory—for the British.

After the battle, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia who had been forced to flee the capital of Williamsburg and form a government in exile aboard the warship HMS Fowey, ordered the British standard raised before making a startling announcement. For the first time in public he formally read a proclamation that he had issued the previous week granting freedom to the slaves of rebels who escaped to British custody.

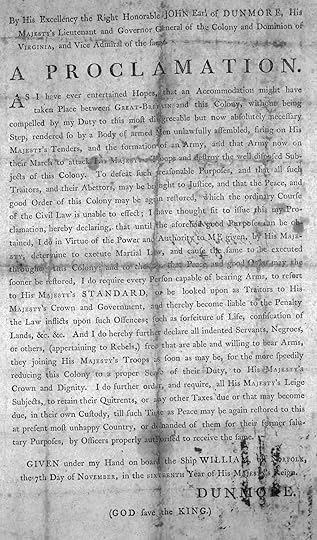

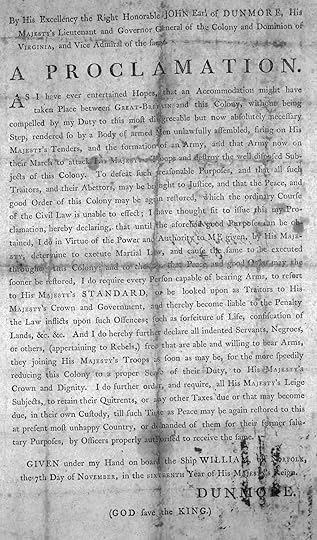

A copy of Dunmore’s Proclamation, issued November 7, 1775.

Library of Congress

Dunmore’s Proclamation was “more an announcement of military strategy than a pronouncement of abolitionist principles,” according to author Gary B. Nash in “The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America.” The document not only provided the British with an immediate source of manpower, it weakened Virginia’s patriots by depriving them of their main source of labor.

Much like Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, however, Dunmore’s Proclamation was limited in scope. Careful not to alienate Britain’s white Loyalist allies, the measure applied only to slaves whose masters were in rebellion against the Crown. The British regularly returned slaves who fled from Loyalist masters.

Dunmore’s Proclamation inspired thousands of slaves to risk their lives in search of freedom. They swam, dog-paddled and rowed to Dunmore’s floating government-in-exile on Chesapeake Bay in order to find protection with the British forces. “By mid-1776, what had been a small stream of escaping slaves now turned into a torrent,” wrote Nash. “Over the next seven years, enslaved Africans mounted the greatest slave rebellion in American history.”

Among those slaves making a break for freedom were eight belonging to Peyton Randolph, speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses, and several belonging to patriot orator Patrick Henry who apparently took his famous words—“Give me liberty, or give me death!”—to heart and fled to British custody. Another runaway who found sanctuary with Dunmore was Harry Washington, who escaped from Mount Vernon while his famous master led the Continental Army.

Dunmore placed these “Black Loyalists” in the newly formed Ethiopian Regiment and had the words “Liberty to Slaves” embroidered on their uniform sashes. Since the idea of escaped slaves armed with guns stirred terror even among white Loyalists, Dunmore placated the slaveholders by primarily using the runaways as laborers building forts, bridges and trenches and engaging in trades such as shoemaking, blacksmithing and carpentry. Women worked as nurses, cooks and seamstresses.

As manpower issues grew more dire as the war progressed, however, the British army became more amenable to arming runaway slaves and sending them into battle. General Henry Clinton organized an all-black regiment, the “Black Pioneers.” Among the hundreds of runaway slaves in its ranks was Harry Washington, who rose to the rank of corporal and participated in the siege of Charleston.

On June 30, 1779, Clinton expanded on Dunmore’s actions and issued the Philipsburg Proclamation, which promised protection and freedom to all slaves in the colonies who escaped from their patriot masters. Blacks captured fighting for the enemy, however, would be sold into bondage.

Colonel Tye, pictured left from the center, depicted fighting with the British in the painting The Death of Major Peirsons. Universal History Archive/Getty Images

According to Maya Jasanoff in her book “Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World,” approximately 20,000 black slaves joined the British during the American Revolution. In contrast, historians estimate that only about 5,000 black men served in the Continental Army.

As the American Revolution came to close with the British defeat at Yorktown in 1781, white Loyalists and thousands of their slaves evacuated Savannah and Charleston and resettled in Florida and on plantations in the Bahamas, Jamaica and other British territories throughout the Caribbean. The subsequent peace negotiations called for all slaves who escaped behind British lines before November 30, 1782, to be freed with restitution given to their owners. In order to determine which African-Americans were eligible for freedom and which weren’t, the British verified the names, ages and dates of escape for every runaway slave in their custody and recorded the information in what was called the “Book of Negroes.”

With their certificates of freedom in hand, 3,000 black men, women and children joined the Loyalist exodus from New York to Nova Scotia in 1783. There the Black Loyalists found freedom, but little else. After years of economic hardship and denial of the land and provisions they had been promised, nearly half of the Black Loyalists abandoned the Canadian province. Approximately 400 sailed to London, while in 1792 more than 1,200 brought their stories full circle and returned to Africa in a new settlement in Sierra Leone. Among the newly relocated was the former slave of the newly elected president of the United States—Harry Washington—who returned to the land of his birth.

Source: History.com

More:

by

by

Maya Jasanoff

Maya Jasanoff

by

by

Gary B. Nash

Gary B. Nash

While the patriots battled for freedom from Great Britain, upwards of 20,000 runaway slaves declared their own personal independence and fought on the side of the British.

When American colonists took up arms in a battle for independence starting in 1775, that fight for freedom excluded an entire race of people—African-Americans. On November 12, 1775, General George Washington decreed in his orders that “neither negroes, boys unable to bear arms, nor old men” could enlist in the Continental Army.

Two days after the patriots’ military leader banned African-Americans from joining his ranks, however, black soldiers proved their mettle at the Battle of Kemp’s Landing along the Virginia coast. They captured an enemy commanding officer and proved pivotal in securing the victory—for the British.

After the battle, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia who had been forced to flee the capital of Williamsburg and form a government in exile aboard the warship HMS Fowey, ordered the British standard raised before making a startling announcement. For the first time in public he formally read a proclamation that he had issued the previous week granting freedom to the slaves of rebels who escaped to British custody.

A copy of Dunmore’s Proclamation, issued November 7, 1775.

Library of Congress

Dunmore’s Proclamation was “more an announcement of military strategy than a pronouncement of abolitionist principles,” according to author Gary B. Nash in “The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America.” The document not only provided the British with an immediate source of manpower, it weakened Virginia’s patriots by depriving them of their main source of labor.

Much like Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, however, Dunmore’s Proclamation was limited in scope. Careful not to alienate Britain’s white Loyalist allies, the measure applied only to slaves whose masters were in rebellion against the Crown. The British regularly returned slaves who fled from Loyalist masters.

Dunmore’s Proclamation inspired thousands of slaves to risk their lives in search of freedom. They swam, dog-paddled and rowed to Dunmore’s floating government-in-exile on Chesapeake Bay in order to find protection with the British forces. “By mid-1776, what had been a small stream of escaping slaves now turned into a torrent,” wrote Nash. “Over the next seven years, enslaved Africans mounted the greatest slave rebellion in American history.”

Among those slaves making a break for freedom were eight belonging to Peyton Randolph, speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses, and several belonging to patriot orator Patrick Henry who apparently took his famous words—“Give me liberty, or give me death!”—to heart and fled to British custody. Another runaway who found sanctuary with Dunmore was Harry Washington, who escaped from Mount Vernon while his famous master led the Continental Army.

Dunmore placed these “Black Loyalists” in the newly formed Ethiopian Regiment and had the words “Liberty to Slaves” embroidered on their uniform sashes. Since the idea of escaped slaves armed with guns stirred terror even among white Loyalists, Dunmore placated the slaveholders by primarily using the runaways as laborers building forts, bridges and trenches and engaging in trades such as shoemaking, blacksmithing and carpentry. Women worked as nurses, cooks and seamstresses.

As manpower issues grew more dire as the war progressed, however, the British army became more amenable to arming runaway slaves and sending them into battle. General Henry Clinton organized an all-black regiment, the “Black Pioneers.” Among the hundreds of runaway slaves in its ranks was Harry Washington, who rose to the rank of corporal and participated in the siege of Charleston.

On June 30, 1779, Clinton expanded on Dunmore’s actions and issued the Philipsburg Proclamation, which promised protection and freedom to all slaves in the colonies who escaped from their patriot masters. Blacks captured fighting for the enemy, however, would be sold into bondage.

Colonel Tye, pictured left from the center, depicted fighting with the British in the painting The Death of Major Peirsons. Universal History Archive/Getty Images

According to Maya Jasanoff in her book “Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World,” approximately 20,000 black slaves joined the British during the American Revolution. In contrast, historians estimate that only about 5,000 black men served in the Continental Army.

As the American Revolution came to close with the British defeat at Yorktown in 1781, white Loyalists and thousands of their slaves evacuated Savannah and Charleston and resettled in Florida and on plantations in the Bahamas, Jamaica and other British territories throughout the Caribbean. The subsequent peace negotiations called for all slaves who escaped behind British lines before November 30, 1782, to be freed with restitution given to their owners. In order to determine which African-Americans were eligible for freedom and which weren’t, the British verified the names, ages and dates of escape for every runaway slave in their custody and recorded the information in what was called the “Book of Negroes.”

With their certificates of freedom in hand, 3,000 black men, women and children joined the Loyalist exodus from New York to Nova Scotia in 1783. There the Black Loyalists found freedom, but little else. After years of economic hardship and denial of the land and provisions they had been promised, nearly half of the Black Loyalists abandoned the Canadian province. Approximately 400 sailed to London, while in 1792 more than 1,200 brought their stories full circle and returned to Africa in a new settlement in Sierra Leone. Among the newly relocated was the former slave of the newly elected president of the United States—Harry Washington—who returned to the land of his birth.

Source: History.com

More:

by

by

Maya Jasanoff

Maya Jasanoff by

by

Gary B. Nash

Gary B. Nash

message 9:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 11:04PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

After reading the Klein article (which I hope you will do) - what are your impressions of Washington's motivations for leading the Continental Army? What did you think about the British terms for peace giving freedom to those slaves who fought for the British and restitution to their owners at the same time? Were you surprised that even Harry Washington was among them and ended up being taken back to the land of his birth to a settlement in Sierra Leone?

This portrait of an unidentified Revolutionary War sailor was painted in oil by an unknown artist, circa 1780. Prior to the war, many blacks were already experienced seamen, having served in the British navy and in the colonies' state navies, as well as on merchant vessels in the North and the South. This sailor's dress uniform suggests that he served in the navy, rather than with a privateer. Image Credit: The Newport Historical Society (P999)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sierra_...

https://www.americanrevolution.org/bl...

https://notevenpast.org/black-loyalis...

(no image) The Negro Revolution in America by William Brink (no photo)

by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo)

by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo)

by Alan Gilbert (no photo)

by Alan Gilbert (no photo)

by Woody Holton (no photo)

by Woody Holton (no photo)

by W.B. Hartgrove (no photo)

by W.B. Hartgrove (no photo)

by Vincent Carretta (no photo)

by Vincent Carretta (no photo)

by Sidney Kaplan (no photo)

by Sidney Kaplan (no photo)

by William Allison Sweeney (no photo)

by William Allison Sweeney (no photo)

by Jim Piecuch (no photo)

by Jim Piecuch (no photo)

by

by

William Cooper Nell

William Cooper Nell

by

by

Gordon S. Wood

Gordon S. Wood

by

by

Benjamin Arthur Quarles

Benjamin Arthur Quarles

by

by

William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown

by

by

George Henry Moore

George Henry Moore

by

by

Gary B. Nash

Gary B. Nash

by

by

Sylvia R. Frey

Sylvia R. Frey

Source: PBS, The Newport Historical Society, Wikipedia, history.com

This portrait of an unidentified Revolutionary War sailor was painted in oil by an unknown artist, circa 1780. Prior to the war, many blacks were already experienced seamen, having served in the British navy and in the colonies' state navies, as well as on merchant vessels in the North and the South. This sailor's dress uniform suggests that he served in the navy, rather than with a privateer. Image Credit: The Newport Historical Society (P999)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sierra_...

https://www.americanrevolution.org/bl...

https://notevenpast.org/black-loyalis...

(no image) The Negro Revolution in America by William Brink (no photo)

by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo)

by Michael Lee Lanning (no photo) by Alan Gilbert (no photo)

by Alan Gilbert (no photo) by Woody Holton (no photo)

by Woody Holton (no photo) by W.B. Hartgrove (no photo)

by W.B. Hartgrove (no photo) by Vincent Carretta (no photo)

by Vincent Carretta (no photo) by Sidney Kaplan (no photo)

by Sidney Kaplan (no photo) by William Allison Sweeney (no photo)

by William Allison Sweeney (no photo) by Jim Piecuch (no photo)

by Jim Piecuch (no photo) by

by

William Cooper Nell

William Cooper Nell by

by

Gordon S. Wood

Gordon S. Wood by

by

Benjamin Arthur Quarles

Benjamin Arthur Quarles by

by

William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown by

by

George Henry Moore

George Henry Moore by

by

Gary B. Nash

Gary B. Nash by

by

Sylvia R. Frey

Sylvia R. FreySource: PBS, The Newport Historical Society, Wikipedia, history.com

message 10:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 11:14PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

It doesn't sound like Lord Dunsmore was the brave soul that he depicted in his note to London does it? He fled in the dark of night and paid back the colonists (he called them rebels) what was owed to them because of his theft.

And, of course, heaven forbid if he had any Catholic blood in his veins so "off with the printing press" And then he becomes the "emancipator"! Did anyone think that Gage finally did not look so bad? Your thoughts?

Baffled by Virginians’ “blind and unreasoning fury,” Dunmore brooded in his palace. He peppered London with complaints and with unreliable appraisals of colonial politics, receiving little guidance in return.

In April 1775, even before learning of events in Lexington and Concord, he ordered a marine detachment to confiscate gunpowder from the public magazine in Williamsburg on grounds that “the Negroes might have seized upon it.”

Rebel drums beat and militia “shirtmen”—so named for their distinctive hunting garb—threatened “to seize upon or massacre me,” he told Whitehall.

After reimbursing the rebels £330 for the powder he had impounded, in early June he fled with his family in the dark of night for refuge first aboard the Magdalen, then on the Fowey, and eventually on the Eilbeck, an unrigged merchant tub he renamed for himself.

With his wife and children dispatched to Britain, Dunmore’s dominion was reduced to a gaggle of loyalist merchants, clerks, and scrofulous sailors. Still, with just a few hundred more troops, he wrote London in August, “I could reduce the colony to submission.”

The Gazette would accuse him of “crimes that would even have disgraced the noted pirate Blackbeard.” Most of his felonies involved what were derided as “chicken-stealing expeditions” against coastal plantations, although he also impounded a Norfolk printing press from a seditious publisher who dared suggest that Catholic blood ran through Dunmore’s veins. But then the earl decided to become an emancipator.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (pp. 183-184). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

And, of course, heaven forbid if he had any Catholic blood in his veins so "off with the printing press" And then he becomes the "emancipator"! Did anyone think that Gage finally did not look so bad? Your thoughts?

Baffled by Virginians’ “blind and unreasoning fury,” Dunmore brooded in his palace. He peppered London with complaints and with unreliable appraisals of colonial politics, receiving little guidance in return.

In April 1775, even before learning of events in Lexington and Concord, he ordered a marine detachment to confiscate gunpowder from the public magazine in Williamsburg on grounds that “the Negroes might have seized upon it.”

Rebel drums beat and militia “shirtmen”—so named for their distinctive hunting garb—threatened “to seize upon or massacre me,” he told Whitehall.

After reimbursing the rebels £330 for the powder he had impounded, in early June he fled with his family in the dark of night for refuge first aboard the Magdalen, then on the Fowey, and eventually on the Eilbeck, an unrigged merchant tub he renamed for himself.

With his wife and children dispatched to Britain, Dunmore’s dominion was reduced to a gaggle of loyalist merchants, clerks, and scrofulous sailors. Still, with just a few hundred more troops, he wrote London in August, “I could reduce the colony to submission.”

The Gazette would accuse him of “crimes that would even have disgraced the noted pirate Blackbeard.” Most of his felonies involved what were derided as “chicken-stealing expeditions” against coastal plantations, although he also impounded a Norfolk printing press from a seditious publisher who dared suggest that Catholic blood ran through Dunmore’s veins. But then the earl decided to become an emancipator.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (pp. 183-184). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

message 11:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited May 31, 2020 11:21PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Today's Progress:

Part One - continued: - We continued Part One.

7. THEY FOUGHT, BLED, AND DIED LIKE ENGLISHMEN

Norfolk, Virginia, December 1775 - page 182 - We began discussion and moderator postings for this chapter - up through 184

We have begun this week's reading and what an interesting chapter - chapter 7 is! Remember this week we can discuss any page from the beginning of the book through page 240.

Good night!

Part One - continued: - We continued Part One.

7. THEY FOUGHT, BLED, AND DIED LIKE ENGLISHMEN

Norfolk, Virginia, December 1775 - page 182 - We began discussion and moderator postings for this chapter - up through 184

We have begun this week's reading and what an interesting chapter - chapter 7 is! Remember this week we can discuss any page from the beginning of the book through page 240.

Good night!

message 12:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 01, 2020 06:00AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

All, we can begin posting about Chapters 7 through 9 now. You may respond to any of the discussion questions that I have posted or you can bring up some interesting ideas of your own about the chapters and the book. If you do quote from the book, please note the chapter and page number if you can - it always helps our readers.

You may discuss anything from the beginning of the book through the end of Chapter 9. Spoilers on a spotlighted read can be posted on the glossary thread which is a spoiler thread.

However, always try to assist your fellow members by indicating what chapter and if you can tell us - what page you are referring to. It always helps.

If you discuss books aside from the book we are reading - please provide the full citation. I have added many ancillary books as we go along which you might want to read on your own at a later time.

If you have not introduced yourself and you are new to the conversation (it is never too late to join in), please introduce yourself and tell us where you are from globally - city and state if USA, city and country if you are global - we love to know where everybody is from who is reading with us.

So we begin week four of the reading and discussion. Welcome all.

You may discuss anything from the beginning of the book through the end of Chapter 9. Spoilers on a spotlighted read can be posted on the glossary thread which is a spoiler thread.

However, always try to assist your fellow members by indicating what chapter and if you can tell us - what page you are referring to. It always helps.

If you discuss books aside from the book we are reading - please provide the full citation. I have added many ancillary books as we go along which you might want to read on your own at a later time.

If you have not introduced yourself and you are new to the conversation (it is never too late to join in), please introduce yourself and tell us where you are from globally - city and state if USA, city and country if you are global - we love to know where everybody is from who is reading with us.

So we begin week four of the reading and discussion. Welcome all.

message 13:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 01, 2020 06:50AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Regarding Dunsmore and Slavery:

What are your thoughts regarding these quotes? Pick one and discuss.

First:

In truth, although slavery had begun to disappear in England and Wales, Britain’s colonial economy was built on a scaffold of bondage. Among many examples, the almost two hundred thousand slaves in Jamaica outnumbered whites fifteen to one, and an uprising in 1760 had been suppressed by shooting several hundred blacks. The slave trade, carried largely in British ships, had never been more prosperous than in the years just before the American rebellion, and Britain would remain the world’s foremost slave-trading nation into the nineteenth century.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 184). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Second:

"Liberation applied only to the able-bodied slaves of his foes. There would be no deliverance for his own fifty-seven slaves—abandoned in Williamsburg when he fled and for whom he would claim compensation from the government—nor would loyalists’ chattel be freed. The governor intended to crush a rebellion, not reconfigure the social order.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 185). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Third:

“This pink-cheeked time-server,” as the historian Simon Schama called Dunmore, “had become the patriarch of a great black exodus.” Thomas Jefferson would later claim that from Virginia alone tens of thousands of slaves escaped servitude during the war, a number likely inflated but suggestive of white anxiety.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 185). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Fourth:

"An American letter written on December 6 and subsequently published in a London newspaper captured the prevailing sentiment: “Hell itself could not have vomited anything more black than his design of emancipating our slaves.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 186). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Fifth:

Edward Rutledge, a prominent South Carolina politician, wrote in December that arming freed slaves tended “more effectually to work an eternal separation between Great Britain and the colonies than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of.” >Had the British “searched through the world for a person the best fitted to ruin their cause,” wrote Richard Henry Lee, “they could not have found a more complete agent than Lord Dunmore.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 186). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Sixth:

"No slave master was more incensed than General Washington. “That arch traitor to the rights of humanity, Lord Dunmore, should be instantly crushed, if it takes the force of the whole colony to do it,” he wrote. In another outburst from Cambridge, Washington told Lee, “Nothing less than depriving him of life or liberty will secure peace in Virginia.” Otherwise, the governor “will become the most formidable enemy America has.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 186). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

What are your thoughts regarding these quotes? Pick one and discuss.

First:

In truth, although slavery had begun to disappear in England and Wales, Britain’s colonial economy was built on a scaffold of bondage. Among many examples, the almost two hundred thousand slaves in Jamaica outnumbered whites fifteen to one, and an uprising in 1760 had been suppressed by shooting several hundred blacks. The slave trade, carried largely in British ships, had never been more prosperous than in the years just before the American rebellion, and Britain would remain the world’s foremost slave-trading nation into the nineteenth century.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 184). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Second:

"Liberation applied only to the able-bodied slaves of his foes. There would be no deliverance for his own fifty-seven slaves—abandoned in Williamsburg when he fled and for whom he would claim compensation from the government—nor would loyalists’ chattel be freed. The governor intended to crush a rebellion, not reconfigure the social order.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 185). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Third:

“This pink-cheeked time-server,” as the historian Simon Schama called Dunmore, “had become the patriarch of a great black exodus.” Thomas Jefferson would later claim that from Virginia alone tens of thousands of slaves escaped servitude during the war, a number likely inflated but suggestive of white anxiety.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 185). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Fourth:

"An American letter written on December 6 and subsequently published in a London newspaper captured the prevailing sentiment: “Hell itself could not have vomited anything more black than his design of emancipating our slaves.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 186). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Fifth:

Edward Rutledge, a prominent South Carolina politician, wrote in December that arming freed slaves tended “more effectually to work an eternal separation between Great Britain and the colonies than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of.” >Had the British “searched through the world for a person the best fitted to ruin their cause,” wrote Richard Henry Lee, “they could not have found a more complete agent than Lord Dunmore.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 186). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Sixth:

"No slave master was more incensed than General Washington. “That arch traitor to the rights of humanity, Lord Dunmore, should be instantly crushed, if it takes the force of the whole colony to do it,” he wrote. In another outburst from Cambridge, Washington told Lee, “Nothing less than depriving him of life or liberty will secure peace in Virginia.” Otherwise, the governor “will become the most formidable enemy America has.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 186). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

message 14:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 01, 2020 07:04AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

The colonists burned as well:

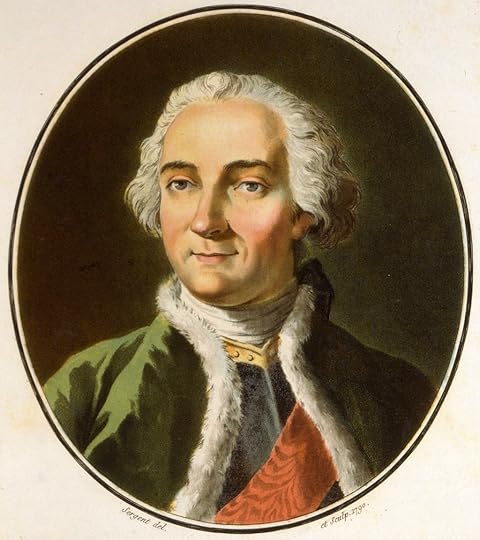

“The detested town of Norfolk is no more!” a midshipman wrote. The “dirty little borough,” now reduced to ash and skeletal chimneys, had suffered greater damage than would befall any town in America during the Revolution.

An investigative commission the following year found that of 1,331 structures destroyed in and near Norfolk, the British had demolished 32 before evacuating the town, then burned 19 more during the January 1 bombardment.

Militia troops burned 863 in early January, and another 416 in the subsequent razing ordered by the convention. But that accounting remained secret for sixty years and then was buried in a legislative journal that stayed hidden for another century, as the historian John E. Selby would note.

Blaming the redcoats for wanton destruction was convenient, and like ruined Falmouth in Maine or Charlestown in Massachusetts, Norfolk became a vivid emblem of British cruelty.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (pp. 192-193). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Discussion Questions:

1. What did either the British or the colonists hope to gain by burning the towns? That certainly was not going to bring the conflict to an end sooner - only dragging it out and/or making it worse.

2. It appeared that both sides did not have control of their troops and "revenge" seemed to run rampant. What were your thoughts on the passage regarding the title of this chapter? I decided not to copy it here because it was entirely offensive.

“The detested town of Norfolk is no more!” a midshipman wrote. The “dirty little borough,” now reduced to ash and skeletal chimneys, had suffered greater damage than would befall any town in America during the Revolution.

An investigative commission the following year found that of 1,331 structures destroyed in and near Norfolk, the British had demolished 32 before evacuating the town, then burned 19 more during the January 1 bombardment.

Militia troops burned 863 in early January, and another 416 in the subsequent razing ordered by the convention. But that accounting remained secret for sixty years and then was buried in a legislative journal that stayed hidden for another century, as the historian John E. Selby would note.

Blaming the redcoats for wanton destruction was convenient, and like ruined Falmouth in Maine or Charlestown in Massachusetts, Norfolk became a vivid emblem of British cruelty.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (pp. 192-193). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Discussion Questions:

1. What did either the British or the colonists hope to gain by burning the towns? That certainly was not going to bring the conflict to an end sooner - only dragging it out and/or making it worse.

2. It appeared that both sides did not have control of their troops and "revenge" seemed to run rampant. What were your thoughts on the passage regarding the title of this chapter? I decided not to copy it here because it was entirely offensive.

message 15:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 01, 2020 07:10AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Today's Progress - June 1st.

Week Four (June 1st - June 7th) - pages 182 - 240

✓Part One - continued: (We continued Part One)

✓7. THEY FOUGHT, BLED, AND DIED LIKE ENGLISHMEN

Norfolk, Virginia, December 1775 - page 182 - We completed this chapter today.

8. THE PATHS OF GLORY - We will begin this chapter tomorrow.

Quebec, December 3, 1775–January 1, 1776 - page 195

Part Two - page 217

9. THE WAYS OF HEAVEN ARE DARK AND INTRICATE - Not started yet.

Boston, January – February 1776 - page 219

Folks, all readers - please select some of the discussion questions and post your responses, opinions, ideas etc. There are no right or wrong answers.

This is where we are at the end of day today.

Have a good day!

Week Four (June 1st - June 7th) - pages 182 - 240

✓Part One - continued: (We continued Part One)

✓7. THEY FOUGHT, BLED, AND DIED LIKE ENGLISHMEN

Norfolk, Virginia, December 1775 - page 182 - We completed this chapter today.

8. THE PATHS OF GLORY - We will begin this chapter tomorrow.

Quebec, December 3, 1775–January 1, 1776 - page 195

Part Two - page 217

9. THE WAYS OF HEAVEN ARE DARK AND INTRICATE - Not started yet.

Boston, January – February 1776 - page 219

Folks, all readers - please select some of the discussion questions and post your responses, opinions, ideas etc. There are no right or wrong answers.

This is where we are at the end of day today.

Have a good day!

message 16:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 02, 2020 11:02AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And so we begin Chapter Eight - The Paths of Glory

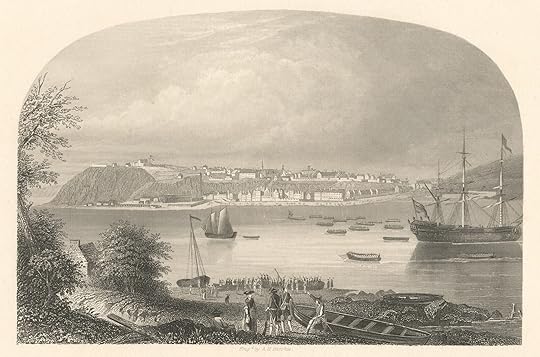

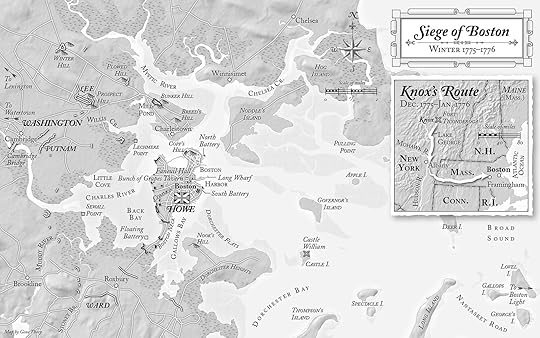

8. The Paths of Glory QUEBEC, DECEMBER 3, 1775–JANUARY 1, 1776

A lowering sky the color of slag hung over Pointe-aux-Trembles at ten a.m. on Sunday, December 3.

Although it was cold enough to split stone, as the habitants said, the sight of canvas sails gliding down the St. Lawrence brought Colonel Benedict Arnold and his troops tromping through foot-deep snow from their flint cobble farmhouses to the river’s edge.

The brig Gaspé, the schooner Mary, and several smaller vessels—all seized from the British as they’d tried to flee Montreal a fortnight earlier—rounded a point on the north bank, nosing through patches of ice, then hove to and dropped their anchors. Cheers echoed through the aspens as a skiff from the little flotilla scraped onto the beach and Brigadier General Richard Montgomery stepped ashore, ready to complete the conquest of Quebec.

Three hundred soldiers came with him, mostly New Yorkers in captured British uniforms. They brought the combined American invasion force to just under a thousand, half the number Arnold had estimated would be needed to overwhelm Fortress Quebec.

Many of Montgomery’s New Englanders, including the Green Mountain Boys, had bolted south after Montreal’s surrender. “They have such an intemperate desire to return home,” General Schuyler told Congress in a note from Ticonderoga, “that nothing can equal it.”

If short of manpower, Montgomery brought ample munitions and winter garb confiscated from enemy stocks: cannons and mortars; sealskin moccasins, red cloth caps trimmed in fur, and underjackets with corduroy sleeves; full-skirted, hooded white overcoats; and more new uniforms from Britain that had been intended for the 26th and 7th Regiments. Forty more barrels of gunpowder—two tons—would shortly follow from Montreal.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 195). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Discussion Questions:

1. Since General Richard Montgomery's troops (now New Yorkers) seem to have donned the British uniforms - I wonder whether it was difficult for their own troops to be recognized and not fired upon? Did anyone else think that this group must have looked like a motley crew indeed? They were obviously well stocked having taken the British supplies, uniforms and other clothing, etc.

2. What impression was given by the author regarding the New Englanders and the rapid departure of the Green Mountain Boys? Do you think that Schuyler was just stating a fact or was there a bit of resentment in his note? Why did Atkinson include this detail?

3. What color did you assume was meant by the color of slag?

8. The Paths of Glory QUEBEC, DECEMBER 3, 1775–JANUARY 1, 1776

A lowering sky the color of slag hung over Pointe-aux-Trembles at ten a.m. on Sunday, December 3.

Although it was cold enough to split stone, as the habitants said, the sight of canvas sails gliding down the St. Lawrence brought Colonel Benedict Arnold and his troops tromping through foot-deep snow from their flint cobble farmhouses to the river’s edge.

The brig Gaspé, the schooner Mary, and several smaller vessels—all seized from the British as they’d tried to flee Montreal a fortnight earlier—rounded a point on the north bank, nosing through patches of ice, then hove to and dropped their anchors. Cheers echoed through the aspens as a skiff from the little flotilla scraped onto the beach and Brigadier General Richard Montgomery stepped ashore, ready to complete the conquest of Quebec.

Three hundred soldiers came with him, mostly New Yorkers in captured British uniforms. They brought the combined American invasion force to just under a thousand, half the number Arnold had estimated would be needed to overwhelm Fortress Quebec.

Many of Montgomery’s New Englanders, including the Green Mountain Boys, had bolted south after Montreal’s surrender. “They have such an intemperate desire to return home,” General Schuyler told Congress in a note from Ticonderoga, “that nothing can equal it.”

If short of manpower, Montgomery brought ample munitions and winter garb confiscated from enemy stocks: cannons and mortars; sealskin moccasins, red cloth caps trimmed in fur, and underjackets with corduroy sleeves; full-skirted, hooded white overcoats; and more new uniforms from Britain that had been intended for the 26th and 7th Regiments. Forty more barrels of gunpowder—two tons—would shortly follow from Montreal.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 195). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Discussion Questions:

1. Since General Richard Montgomery's troops (now New Yorkers) seem to have donned the British uniforms - I wonder whether it was difficult for their own troops to be recognized and not fired upon? Did anyone else think that this group must have looked like a motley crew indeed? They were obviously well stocked having taken the British supplies, uniforms and other clothing, etc.

2. What impression was given by the author regarding the New Englanders and the rapid departure of the Green Mountain Boys? Do you think that Schuyler was just stating a fact or was there a bit of resentment in his note? Why did Atkinson include this detail?

3. What color did you assume was meant by the color of slag?

Philip Schuyler

Tall, thin, and florid, with kinky hair and erratic health, Major General Philip Schuyler was among America’s wealthiest, most accomplished men. He would command the invasion of Canada in 1775. - Ph. Schuyler, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

Surrender of General Burgoyne, by John Trumbull, c. 1821. Courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol. Schuyler can be seen on the right side of the portrait, dressed in brown.

Philip Schuyler was born on November 11, 1733 in Albany, New York to parents Johannes “John” Schuyler Jr. and Cornelia Van Cortlandt. Schuyler’s family migrated from Amsterdam in 1650 and were related to the families of the old Dutch aristocracy. Schuyler’s second great-grandfather was the first mayor of Albany, New York, the place of his birth.

Philip Schuyler began his military service during the French and Indian War as a captain and was later promoted to major. He partook in the battles of Lake George, Oswego River, Ticonderoga, and Fort Frontenac.

After his first stretch in the military, Schuyler ventured into politics. He began his tenure as a New York State Assemblyman in 1768 and served until 1775 when he was selected as a delegate to the second Continental Congress in May of that year. On June 19, 1775, he was commissioned as one of only four major generals in the Continental Army. He established his headquarters in Albany, NY and began planning an invasion of Canada. Early into his campaign he was plagued with a medical condition that caused command to be deferred to General Richard Montgomery. After leaving his regiment he returned to Fort Ticonderoga and then later to his hometown of Albany. He remained there for the winter of 1775 to 1776 where he collected supplies and forwarded them to Canada. He also aided the American effort in subduing British forces in the Mohawk Valley region of Western New York.

Schuyler’s original plan to invade Canada fell short upon the death of General Montgomery and the Patriot force’s failure to capture Quebec. Upon the American troops’ retreat to Crown Point and the evacuation of Fort Ticonderoga, General Horatio Gates attempted to claim precedence over Schuyler and sought Schuyler’s dismissal from service. The matter was taken up in front of Congress and Schuyler was superseded in August of 1777. Schuyler requested a trial in military court to prove his case. Schuyler was acquitted on all charges in 1778, but his reputation was still damaged. He resigned from military service in April of 1779.

Upon his departure from military service he reentered politics and served first as a delegate from New York to the Continental Congress from 1797 to 1781 and then three terms in the New York State Senate from 1781 to 1997. He served a term as a United States Senator from New York but lost his seat to Aaron Burr, who’s campaign was backed by enemies of Schuyler. Alexander Hamilton was enraged by the Schuyler’s loss, as Hamilton backed his campaign due to his support of New York ratifying the Federal constitution.

In addition to being a political ally of Schuyler’s, Alexander Hamilton married Schuyler’s daughter, Elizabeth, in 1780. Once Hamilton regained control of New York State politics, Schuyler won back his seat in the United States Senate from Aaron Burr in 1797. Schuyler served only a few years of his term before resigning due to poor health. Philip Schuyler died on November 18, 1804.

Schuyler Mansion

Source: American Battlefield Trust, Encyclopedia Britannica, PBS, New Netherland Institute, Fandom, American Revolutionary War, Founders Archive, Schuyler Mansion, Albany Institute, Mount Vernon, Find a Grave, Times Union, Congress, National Park Service, Union College, Smithsonian

More:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexpe...

https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.or...

https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.or...

https://www.myrevolutionarywar.com/le...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

http://schuylermansion.blogspot.com/p...

https://www.albanyinstitute.org/the-s...

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9...

https://www.timesunion.com/albanyrura...

https://bioguideretro.congress.gov/Ho...

https://www.nps.gov/sara/planyourvisi...

http://threerivershms.com/schuylerman...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen... (discussing a later yellow fever epidemic)

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/c...

https://www.union.edu/news/stories/20...

by Benson John Lossing (no photo)

by Benson John Lossing (no photo)

(no image) Proud Patriot: Philip Schuyler And The War Of Independence, 1775 1783 by Don R. Gerlach (no photo)

(no image) Proud Patriot: Philip Schuyler And The War Of Independence, 1775 1783 by Don R. Gerlach (no photo)

(no image) Revolutionary enigma; a re-appraisal of General Philip Schuyler of New York by Martin H. Bush (no photo)

Original Summer Home - burned by the British- it was rebuilt

Video: https://www.smithsonianchannel.com/vi...

Video: Interesting -https://youtu.be/WZ9-dZpJBvg (more about Hamilton and Jefferson)

Video: Tour of Schuyler Mansion - https://youtu.be/Ublgp2EpZN8 and https://www.thirteen.org/programs/tre...

Tall, thin, and florid, with kinky hair and erratic health, Major General Philip Schuyler was among America’s wealthiest, most accomplished men. He would command the invasion of Canada in 1775. - Ph. Schuyler, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

Surrender of General Burgoyne, by John Trumbull, c. 1821. Courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol. Schuyler can be seen on the right side of the portrait, dressed in brown.

Philip Schuyler was born on November 11, 1733 in Albany, New York to parents Johannes “John” Schuyler Jr. and Cornelia Van Cortlandt. Schuyler’s family migrated from Amsterdam in 1650 and were related to the families of the old Dutch aristocracy. Schuyler’s second great-grandfather was the first mayor of Albany, New York, the place of his birth.

Philip Schuyler began his military service during the French and Indian War as a captain and was later promoted to major. He partook in the battles of Lake George, Oswego River, Ticonderoga, and Fort Frontenac.

After his first stretch in the military, Schuyler ventured into politics. He began his tenure as a New York State Assemblyman in 1768 and served until 1775 when he was selected as a delegate to the second Continental Congress in May of that year. On June 19, 1775, he was commissioned as one of only four major generals in the Continental Army. He established his headquarters in Albany, NY and began planning an invasion of Canada. Early into his campaign he was plagued with a medical condition that caused command to be deferred to General Richard Montgomery. After leaving his regiment he returned to Fort Ticonderoga and then later to his hometown of Albany. He remained there for the winter of 1775 to 1776 where he collected supplies and forwarded them to Canada. He also aided the American effort in subduing British forces in the Mohawk Valley region of Western New York.

Schuyler’s original plan to invade Canada fell short upon the death of General Montgomery and the Patriot force’s failure to capture Quebec. Upon the American troops’ retreat to Crown Point and the evacuation of Fort Ticonderoga, General Horatio Gates attempted to claim precedence over Schuyler and sought Schuyler’s dismissal from service. The matter was taken up in front of Congress and Schuyler was superseded in August of 1777. Schuyler requested a trial in military court to prove his case. Schuyler was acquitted on all charges in 1778, but his reputation was still damaged. He resigned from military service in April of 1779.

Upon his departure from military service he reentered politics and served first as a delegate from New York to the Continental Congress from 1797 to 1781 and then three terms in the New York State Senate from 1781 to 1997. He served a term as a United States Senator from New York but lost his seat to Aaron Burr, who’s campaign was backed by enemies of Schuyler. Alexander Hamilton was enraged by the Schuyler’s loss, as Hamilton backed his campaign due to his support of New York ratifying the Federal constitution.

In addition to being a political ally of Schuyler’s, Alexander Hamilton married Schuyler’s daughter, Elizabeth, in 1780. Once Hamilton regained control of New York State politics, Schuyler won back his seat in the United States Senate from Aaron Burr in 1797. Schuyler served only a few years of his term before resigning due to poor health. Philip Schuyler died on November 18, 1804.

Schuyler Mansion

Source: American Battlefield Trust, Encyclopedia Britannica, PBS, New Netherland Institute, Fandom, American Revolutionary War, Founders Archive, Schuyler Mansion, Albany Institute, Mount Vernon, Find a Grave, Times Union, Congress, National Park Service, Union College, Smithsonian

More:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexpe...

https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.or...

https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.or...

https://www.myrevolutionarywar.com/le...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

http://schuylermansion.blogspot.com/p...

https://www.albanyinstitute.org/the-s...

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9...

https://www.timesunion.com/albanyrura...

https://bioguideretro.congress.gov/Ho...

https://www.nps.gov/sara/planyourvisi...

http://threerivershms.com/schuylerman...

https://founders.archives.gov/documen... (discussing a later yellow fever epidemic)

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/c...

https://www.union.edu/news/stories/20...

by Benson John Lossing (no photo)

by Benson John Lossing (no photo)(no image) Proud Patriot: Philip Schuyler And The War Of Independence, 1775 1783 by Don R. Gerlach (no photo)

(no image) Proud Patriot: Philip Schuyler And The War Of Independence, 1775 1783 by Don R. Gerlach (no photo)

(no image) Revolutionary enigma; a re-appraisal of General Philip Schuyler of New York by Martin H. Bush (no photo)

Original Summer Home - burned by the British- it was rebuilt

Video: https://www.smithsonianchannel.com/vi...

Video: Interesting -https://youtu.be/WZ9-dZpJBvg (more about Hamilton and Jefferson)

Video: Tour of Schuyler Mansion - https://youtu.be/Ublgp2EpZN8 and https://www.thirteen.org/programs/tre...

message 18:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 02, 2020 12:01PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

General Richard Montgomery

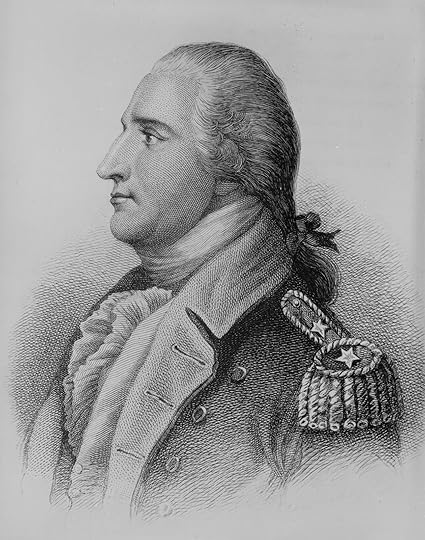

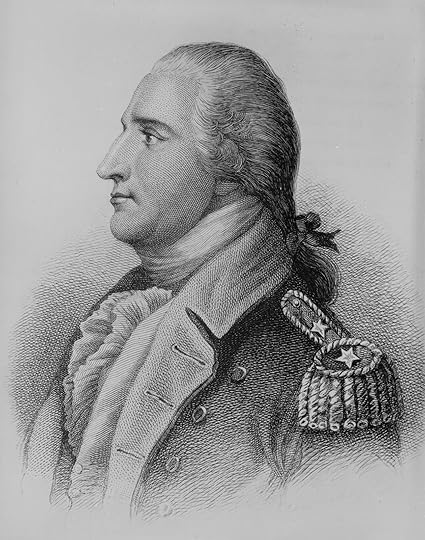

The youngest son of an Irish baronet, Richard Montgomery served sixteen years in the British Army before emigrating to New York in 1772 and accepting an American commission as a brigadier general three years later. “I have been dragged from obscurity much against my inclination,” he told his wife. - Alonzo Chappel, Richd. Montgomery, engraving by George R. Hall, 1881. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

"For his part, General Montcalm wrote an affecting final letter to his wife before riding his black horse onto the Plains of Abraham. “The moment when I shall see you again will be the finest of my life,” he told her. “Goodbye, my heart.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 206). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

"At least not a living soul. Grape hit Montgomery in both thighs and, mortally, through the face. He pitched over backward, knees drawn up, the sword flying from his hand. Behind him Cheeseman fell, rose, and fell again for good, the burial gold still in his pocket. Macpherson never moved. Ten other bodies would be found in the snow at Près de Ville. The survivors had plunged back through the barrier opening, dragging the wounded by their collars."

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 210). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

"Montgomery’s body was found where he fell; a drummer boy scuffing through drifts in Près de Ville also retrieved his sword—a short-bladed hanger with a silver bulldog’s head on the ivory handle. A British officer gave the boy seven shillings for the treasure."

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 213). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

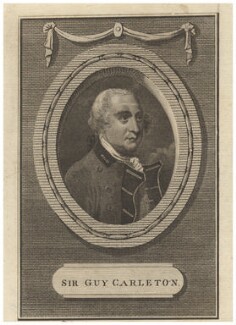

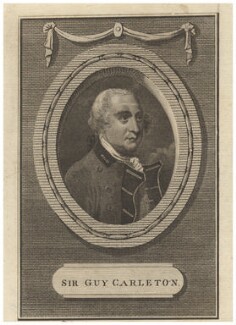

"Thirteen years earlier, at the siege of Havana, Carleton had served as a colonel in one British regiment when Montgomery was a captain in another.

For old times’ sake, the governor asked his carpenters to make a “genteel coffin” of fir lined with flannel and draped in a black pall.

On Wednesday, January 3, regulars from the 7th Foot, their arms reversed and black scarves knotted on their left elbows, led the cortege past the seminary cell windows where American officers wept.

A rocky defile near the St. Louis Gate powder magazine had been used as a Protestant cemetery in Quebec, and here the mortal remains of Richard Montgomery were interred with military honors.

He would never know that the previous month, Congress had promoted him to major general. Nor would he know that his puling threats to resign had brought a rebuke from Washington, who on Christmas Eve wrote Schuyler, “When is the time for brave men to exert themselves in the cause of liberty and their country, if this is not?”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 213). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

"Streets, counties, towns, and children would be named for him. Nor did the adulation soon fade. In June 1818, an American delegation arrived in Quebec, located and identified Montgomery’s body, and took him home."

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 214). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

Montgomery had written his will at Crown Point in August 1775, before marching into Canada; he had divided his estate between Janet and his sister in Ireland.

But in a practice common after battles, his effects at Quebec were inventoried at Holland House on January 3, 1776, and his personal kit then auctioned. Several officers, including Captain Aaron Burr, counted out a bag of coins worth £347, including Spanish milled dollars, gold half-joes, English crowns, Connecticut and Massachusetts shillings, and Continental dollars, plus a string of Indian white wampum.

His sheets went to the convent hospital, “Dick the Negro boy” got a pair of wool socks, and Montgomery’s watch—London-made, with a 22-karat case and a rare ruby cylinder escapement—was saved for Janet after Carleton returned it to the American camp.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 214). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

The youngest son of an Irish baronet, Richard Montgomery served sixteen years in the British Army before emigrating to New York in 1772 and accepting an American commission as a brigadier general three years later. “I have been dragged from obscurity much against my inclination,” he told his wife. - Alonzo Chappel, Richd. Montgomery, engraving by George R. Hall, 1881. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

"For his part, General Montcalm wrote an affecting final letter to his wife before riding his black horse onto the Plains of Abraham. “The moment when I shall see you again will be the finest of my life,” he told her. “Goodbye, my heart.”

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 206). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.

"At least not a living soul. Grape hit Montgomery in both thighs and, mortally, through the face. He pitched over backward, knees drawn up, the sword flying from his hand. Behind him Cheeseman fell, rose, and fell again for good, the burial gold still in his pocket. Macpherson never moved. Ten other bodies would be found in the snow at Près de Ville. The survivors had plunged back through the barrier opening, dragging the wounded by their collars."

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 210). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition.