The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The British Are Coming

AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR

>

SPOTLIGHTED BOOK - THE BRITISH ARE COMING: THE WAR FOR AMERICA, LEXINGTON TO PRINCETON, 1775-1777 (THE REVOLUTION TRILOGY #1) - Week Seven - June 22nd - June 28th, 2020 - Chapters Fifteen and Sixteen (pages 348 - 402) Non Spoiler Thread

This is the reading assignment for this week:

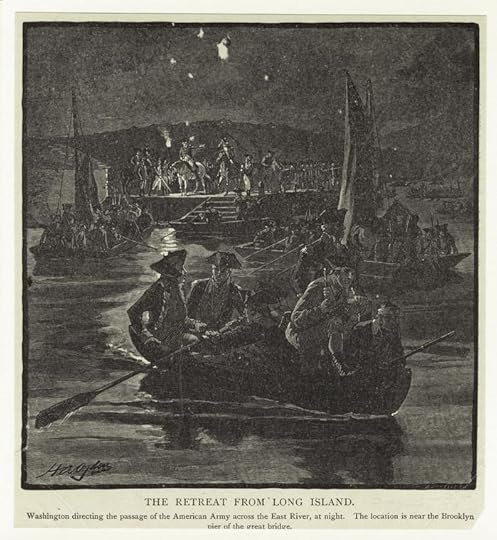

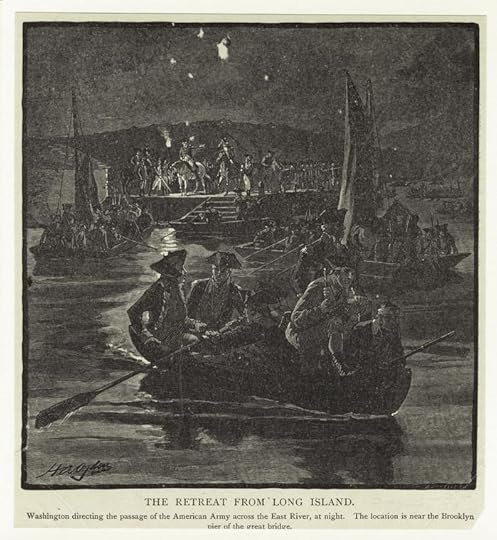

Week Seven: (June 22nd - June 28th)

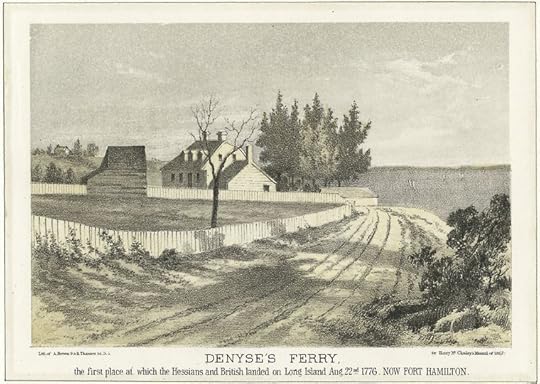

15. A FIGHT AMONG WOLVES New York, July–August 1776 - page 348

16. A SENTIMENTAL MANNER OF MAKING WAR New York, September 1776 - page 380

Folks, on this thread we can discuss anything in the book up through

page 402.

The thread is open.

Week Seven: (June 22nd - June 28th)

15. A FIGHT AMONG WOLVES New York, July–August 1776 - page 348

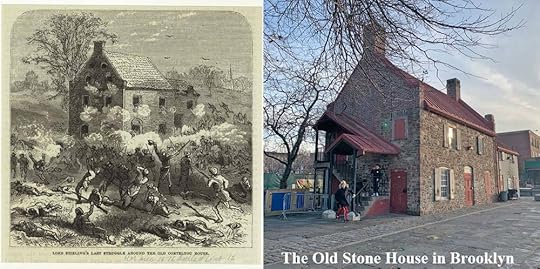

16. A SENTIMENTAL MANNER OF MAKING WAR New York, September 1776 - page 380

Folks, on this thread we can discuss anything in the book up through

page 402.

The thread is open.

message 3:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 22, 2020 03:01AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

All, I suspect that some of you are trying to catch up. Let me know that and I can always slow down or wait for you. But if I do not know we continue on schedule and I do hope you get caught up.

We expect that members who are reading the book will check in at least once per thread to let us know that they are doing ok or have questions or would like to discuss this or that about the book and the assigned reading. We do put up questions and topics for discussion and we do expect that so you can jump right in and discuss the chapters and readings and have a point of reference.

Our discussions are geared so that you can read and discuss each book leisurely but possibly have a couple of other books on the side.

We want to give everybody a chance to get a good history/nonfiction book completed that they have wanted to read.

So welcome to Week Seven!

We expect that members who are reading the book will check in at least once per thread to let us know that they are doing ok or have questions or would like to discuss this or that about the book and the assigned reading. We do put up questions and topics for discussion and we do expect that so you can jump right in and discuss the chapters and readings and have a point of reference.

Our discussions are geared so that you can read and discuss each book leisurely but possibly have a couple of other books on the side.

We want to give everybody a chance to get a good history/nonfiction book completed that they have wanted to read.

So welcome to Week Seven!

message 4:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 22, 2020 11:15PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And so we begin:

Chapter 15.

A Fight Among Wolves

NEW YORK, JULY–AUGUST 1776

"The fateful news traveled swiftly on the post road from Philadelphia, covering more than ninety miles and crossing five rivers in just a couple of days. Precise copies were then made of the thirteen-hundred-word broadside, titled “A Declaration,” that arrived at the Mortier mansion headquarters, and by Tuesday, July 9,

General Washington was ready for every soldier in his command to hear what Congress had to say. In his orders that morning, after affirming thirty-nine lashes for two convicted deserters, he instructed the army to assemble at six p.m. on various parade grounds, from Governors Island to King’s Bridge.

Each brigade major would then read—“with an audible voice”—the proclamation intended to transform a squalid family brawl into a cause as ambitious and righteous as any in human history.

That evening the commander in chief himself appeared on horseback at the Common with a suite of staff officers, not far from where Sergeant Hickey had tumbled from the scaffold two weeks earlier. Erect and somber, Washington rode into the middle of a hollow square formed by New York and Connecticut regiments while a chirpy throng of civilians ringed the greensward.

A uniformed aide spurred his horse forward; the crowd hushed as he unfolded his script and began to read: “In Congress, July 4, 1776.” Even the most unlettered private recognized that something majestic was in the air.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 348). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition

Discussion Topics and Questions:

1. How did George Washington think that he was going to transform his men from a ragtag bunch of colonists into an ambitious and righteous army who would have a cause to fight for?

2. Little did these men know how much they were witnessing history and being a part of the launch of a brand new country and experiment. How noble is the Declaration of Independence and which segments of the document move you the most? What do these words mean to you?

3. Many folks think that we are a democracy but we are a republic. How does a republic derive its power?

4. The fact that at least a third of the delegates who would sign the Declaration were slave owners and the fact that the author of the document - Thomas Jefferson had 200 was according to Atkinson a "moral catastrophe". What was incongruent with the doctrine and the reality? How did Edmund S. Morgan explain the inequities?

5. Why do groups tear down statues and try to negate history? What was the significance of a rambunctious crowd who were also vandals destroying the statue of George III?

6. What was the answer to the Declaration of Independence that General Howe gave the colonists on Friday afternoon, July 12th?

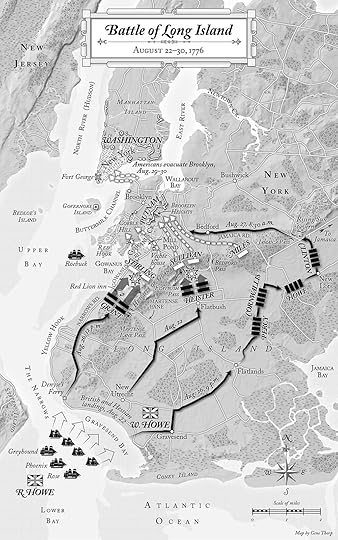

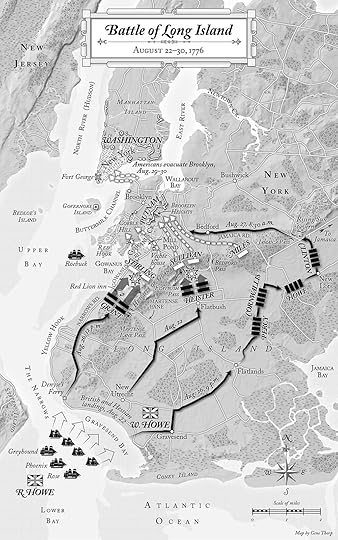

7. How did Washington lose New York, Long Island and the Hudson as well as losing half of his artillery. Why was this a major miscalculation on the part of Washington and how did this happen? What were your thoughts about the retreat?

8. How impossible a situation was defending the colonists' positions in New York City and Long Island (islands surrounded by water) without a Navy? The British had a Navy and were bringing it and a massive number of troops - and they were surrounding the island with war ships. What could Washington have done differently without a Navy?

9. When Sir William Howe (General of the Army) had arrived - he had arrived without all of his ships and he would have to wait another two months for them to arrive - he housed himself for the duration on Staten Island. What could Washington have done - which he did not do - during this time period?

10. Washington had problems forging a "united spirit" among his troops. His militiamen came from various states and parts of the country and they recognized each other as their group (state) versus anything called "America" and there was a lot of rivalry and conflicts between the groups. How did Washington try to forge a new country's identity?

11. According to John Keegan (British historian) in the PBS special I added about the Battle of Long Island - "The real problem was that the British had not treated the colonists officers as gentlemen even "before the war" when they had been "provincial officers". It has been said that if only the British had made George Washington a regular colonel of the armed forces of the Crown - he wouldn't have been a Revolutionary at all. He might have been fighting energetically to put the rebellion down." What do you think of Keegan's assessment of the lack of respect of the British towards the American officers and that of George Washington?

12. Despite George Washington and his men being outnumbered two to one and the fact that they did not have a Navy - were there any bright spots involving the Battle of Long Island and/or the retreat?

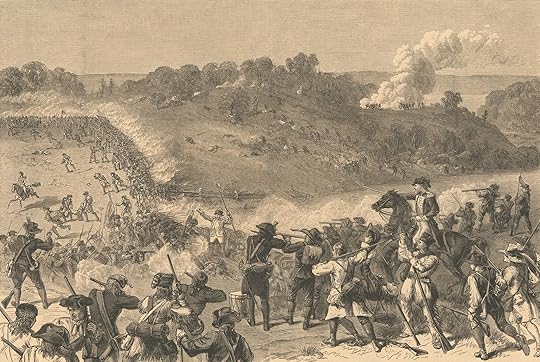

13. Keegan in the PBS special indicates "that even at 300 yards there was no way of hitting anything" - unless you bunched your men up together densely and "in order" and then marched them up with the "officers up front" and then "they did fire upon each other at very close range indeed".

Keegan stated that: "During that time period, a man firing at another 100 yards away had no chance of hitting anyone or anything; the ball might go anywhere - so the only way that you could be certain of inflicting casualties on the enemy was to mass your men as closely as possible together. So both sides massed up into compact clumps and fired at each other - each hoping that the other would run away."

"Once you would have loaded for the first volley - returned your musket and reloaded - the noise was such you couldn't hear anything - you would be very lucky if you could even hear a drum beat and that is why they used drums for commands once the volleying began.

It was then men firing at will and the soldiers just kept firing unless you heard a drum beat or someone yelling in your ear - cease fire. There was no organization after about the third volley."

What do you think of the description of the troops and what occurred after the fighting started? Hard to imagine a worst place to be? How difficult was it to wage war in these circumstances? How disastrous must have been the injuries that these men on both sides suffered?

14. Not knowing the topography - the Americans and George Washington left the Jamaica Pass unguarded and that was their Achilles Heel - a very grave error. General Howe had local Tories guiding him and they found out that the Jamaica Pass on the America's left was virtually unguarded. The Americans not knowing the topography just slipped up and left the Jamaica Pass unguarded. So keeping the Americans occupied in front - another British group slipped through the Jamaica Pass and to the left (on the side) and also came up behind (the American's rear) and then they had the Americans pinned with nowhere to go. The Americans realizing the peril that they found themselves in - just broke and ran. And they only had one escape route - through the Gowanus Marsh.

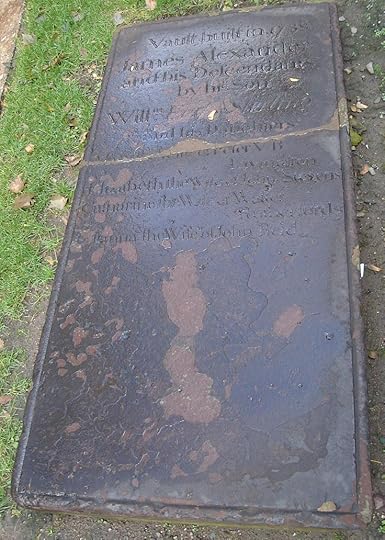

15. The Battle of Brooklyn and the brave men of the 1st Maryland Regiment changed the course of the war when they holed themselves up so that Washington and his men could evacuate. 256 of about 400 brave men would die. 100 would be taken prisoner and only about 10 ever returning to the American lines. How was Washington responsible for this grave error? And why are these brave men buried at Third and Ninth in Brooklyn under a road or a vacant lot with no memoriam? What would have happened if these brave men did not hold their ground?

16. Did you know that the Battle of Long Island (also known as the Battle of Brooklyn) was the largest battle of the American Revolution with roughly 50,000 men engaged (combined - both sides)? And did you know that it was the largest naval landing until D Day in 1942 (World War II)?

17. Cornwallis offered Stirling high praise later saying, “General Stirling fought like a wolf.” What did Cornwallis mean? In fact, Atkinson titled this chapter - A Fight Among Wolves.

18. There has been much conjecture about who or what was at fault for the disaster at the Battle of Long Island (Battle of Brooklyn). Some say it was that the Americans were outnumbered at least 2 to 1 - others say that the Americans did not have a navy and it would be impossible to defend New York against the powerful British Navy; others say that Greene got sick and Sullivan and Putnam were not used to the topography of their assumed command - but in the final analysis - the fault lies with Washington and his lack of experience in a battle of this magnitude.

The American Battlefield Trust explained it this way: "As was typical of Washington’s style of leadership early in the war he failed to reconnoiter his positions and tactically left his flanks unprotected. This would be his army’s undoing at Brooklyn. Loyalists in the area tipped off British commander Henry Clinton that one of the passes that led to Gowanus and Brooklyn Heights was lightly defended by only five members of the local American militia.

What is your take about Washington's style of leadership early in the war?

Chapter 15.

A Fight Among Wolves

NEW YORK, JULY–AUGUST 1776

"The fateful news traveled swiftly on the post road from Philadelphia, covering more than ninety miles and crossing five rivers in just a couple of days. Precise copies were then made of the thirteen-hundred-word broadside, titled “A Declaration,” that arrived at the Mortier mansion headquarters, and by Tuesday, July 9,

General Washington was ready for every soldier in his command to hear what Congress had to say. In his orders that morning, after affirming thirty-nine lashes for two convicted deserters, he instructed the army to assemble at six p.m. on various parade grounds, from Governors Island to King’s Bridge.

Each brigade major would then read—“with an audible voice”—the proclamation intended to transform a squalid family brawl into a cause as ambitious and righteous as any in human history.

That evening the commander in chief himself appeared on horseback at the Common with a suite of staff officers, not far from where Sergeant Hickey had tumbled from the scaffold two weeks earlier. Erect and somber, Washington rode into the middle of a hollow square formed by New York and Connecticut regiments while a chirpy throng of civilians ringed the greensward.

A uniformed aide spurred his horse forward; the crowd hushed as he unfolded his script and began to read: “In Congress, July 4, 1776.” Even the most unlettered private recognized that something majestic was in the air.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Source: Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming (The Revolution Trilogy) (p. 348). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition

Discussion Topics and Questions:

1. How did George Washington think that he was going to transform his men from a ragtag bunch of colonists into an ambitious and righteous army who would have a cause to fight for?

2. Little did these men know how much they were witnessing history and being a part of the launch of a brand new country and experiment. How noble is the Declaration of Independence and which segments of the document move you the most? What do these words mean to you?

3. Many folks think that we are a democracy but we are a republic. How does a republic derive its power?

4. The fact that at least a third of the delegates who would sign the Declaration were slave owners and the fact that the author of the document - Thomas Jefferson had 200 was according to Atkinson a "moral catastrophe". What was incongruent with the doctrine and the reality? How did Edmund S. Morgan explain the inequities?

5. Why do groups tear down statues and try to negate history? What was the significance of a rambunctious crowd who were also vandals destroying the statue of George III?

6. What was the answer to the Declaration of Independence that General Howe gave the colonists on Friday afternoon, July 12th?

7. How did Washington lose New York, Long Island and the Hudson as well as losing half of his artillery. Why was this a major miscalculation on the part of Washington and how did this happen? What were your thoughts about the retreat?

8. How impossible a situation was defending the colonists' positions in New York City and Long Island (islands surrounded by water) without a Navy? The British had a Navy and were bringing it and a massive number of troops - and they were surrounding the island with war ships. What could Washington have done differently without a Navy?

9. When Sir William Howe (General of the Army) had arrived - he had arrived without all of his ships and he would have to wait another two months for them to arrive - he housed himself for the duration on Staten Island. What could Washington have done - which he did not do - during this time period?

10. Washington had problems forging a "united spirit" among his troops. His militiamen came from various states and parts of the country and they recognized each other as their group (state) versus anything called "America" and there was a lot of rivalry and conflicts between the groups. How did Washington try to forge a new country's identity?

11. According to John Keegan (British historian) in the PBS special I added about the Battle of Long Island - "The real problem was that the British had not treated the colonists officers as gentlemen even "before the war" when they had been "provincial officers". It has been said that if only the British had made George Washington a regular colonel of the armed forces of the Crown - he wouldn't have been a Revolutionary at all. He might have been fighting energetically to put the rebellion down." What do you think of Keegan's assessment of the lack of respect of the British towards the American officers and that of George Washington?

12. Despite George Washington and his men being outnumbered two to one and the fact that they did not have a Navy - were there any bright spots involving the Battle of Long Island and/or the retreat?

13. Keegan in the PBS special indicates "that even at 300 yards there was no way of hitting anything" - unless you bunched your men up together densely and "in order" and then marched them up with the "officers up front" and then "they did fire upon each other at very close range indeed".

Keegan stated that: "During that time period, a man firing at another 100 yards away had no chance of hitting anyone or anything; the ball might go anywhere - so the only way that you could be certain of inflicting casualties on the enemy was to mass your men as closely as possible together. So both sides massed up into compact clumps and fired at each other - each hoping that the other would run away."

"Once you would have loaded for the first volley - returned your musket and reloaded - the noise was such you couldn't hear anything - you would be very lucky if you could even hear a drum beat and that is why they used drums for commands once the volleying began.

It was then men firing at will and the soldiers just kept firing unless you heard a drum beat or someone yelling in your ear - cease fire. There was no organization after about the third volley."

What do you think of the description of the troops and what occurred after the fighting started? Hard to imagine a worst place to be? How difficult was it to wage war in these circumstances? How disastrous must have been the injuries that these men on both sides suffered?

14. Not knowing the topography - the Americans and George Washington left the Jamaica Pass unguarded and that was their Achilles Heel - a very grave error. General Howe had local Tories guiding him and they found out that the Jamaica Pass on the America's left was virtually unguarded. The Americans not knowing the topography just slipped up and left the Jamaica Pass unguarded. So keeping the Americans occupied in front - another British group slipped through the Jamaica Pass and to the left (on the side) and also came up behind (the American's rear) and then they had the Americans pinned with nowhere to go. The Americans realizing the peril that they found themselves in - just broke and ran. And they only had one escape route - through the Gowanus Marsh.

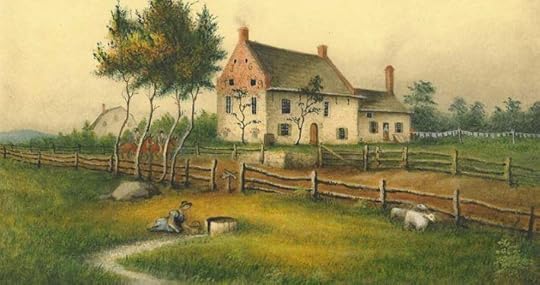

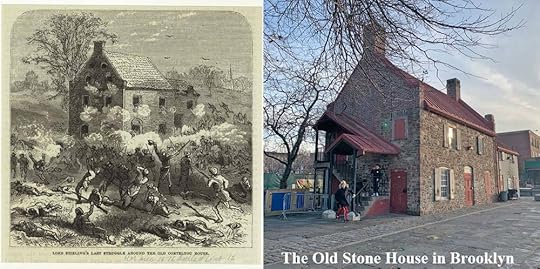

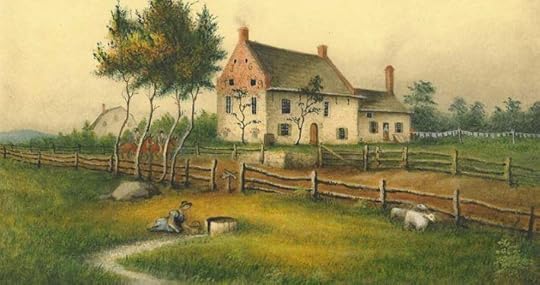

15. The Battle of Brooklyn and the brave men of the 1st Maryland Regiment changed the course of the war when they holed themselves up so that Washington and his men could evacuate. 256 of about 400 brave men would die. 100 would be taken prisoner and only about 10 ever returning to the American lines. How was Washington responsible for this grave error? And why are these brave men buried at Third and Ninth in Brooklyn under a road or a vacant lot with no memoriam? What would have happened if these brave men did not hold their ground?

16. Did you know that the Battle of Long Island (also known as the Battle of Brooklyn) was the largest battle of the American Revolution with roughly 50,000 men engaged (combined - both sides)? And did you know that it was the largest naval landing until D Day in 1942 (World War II)?

17. Cornwallis offered Stirling high praise later saying, “General Stirling fought like a wolf.” What did Cornwallis mean? In fact, Atkinson titled this chapter - A Fight Among Wolves.

18. There has been much conjecture about who or what was at fault for the disaster at the Battle of Long Island (Battle of Brooklyn). Some say it was that the Americans were outnumbered at least 2 to 1 - others say that the Americans did not have a navy and it would be impossible to defend New York against the powerful British Navy; others say that Greene got sick and Sullivan and Putnam were not used to the topography of their assumed command - but in the final analysis - the fault lies with Washington and his lack of experience in a battle of this magnitude.

The American Battlefield Trust explained it this way: "As was typical of Washington’s style of leadership early in the war he failed to reconnoiter his positions and tactically left his flanks unprotected. This would be his army’s undoing at Brooklyn. Loyalists in the area tipped off British commander Henry Clinton that one of the passes that led to Gowanus and Brooklyn Heights was lightly defended by only five members of the local American militia.

What is your take about Washington's style of leadership early in the war?

message 5:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 22, 2020 09:57PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Chapter Overviews and Summaries

August 1776: Council of War in the house of Mr Philip Livingstone in Brooklyn, after the Battle of Long Island. (Photo by Three Lions/Getty Images)

15. A FIGHT AMONG WOLVES

New York,

July–August 1776

George Washington returned from Philadelphia and wanted every soldier in his command to hear the declaration. His hope was that this declaration would transform his army because they now would have an ambitious and righteous cause to fight for.

The Declaration of Independence was read - a document written by Thomas Jefferson who wrote that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, and that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Jefferson claimed later that this was intended to be an expression of the American mind.

A third of the delegates who would sign the Declaration were slave owners and Jefferson had two hundred - so you can see due to their culture - there was a disconnect. But as Edmund S. Morgan would write: "The creed of equality did not give men equality, but invited them to claim it, invited them, not to know their place and keep it, but to seek and demand a better place." This chapter is quite timely in terms of current events.

After the decapitation of the George III statue, General Howe had an answer to the Declaration of Independence, and he sent it on Friday afternoon, July 12th. Washington tried to figure out what would be the Howe brothers next move - would the British continue to push up the Hudson, perhaps in hopes of joining Carleton's force from Canada or would they thread the East River to Long Island Sound, landing behind the American fortifications in New York?

Or would they launch amphibious landings on both Manhattan and Long Island?

In the end, Washington misjudged the strategy of the British and Howe chose the Battle of Long Island.

16. A SENTIMENTAL MANNER OF MAKING WAR

New York

September 1776

Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge were called to a conference with Lord Howe in Staten Island. Howe wanted to discuss putting a stop to the calamities of war.

Franklin retorted that "Forces have been sent out and towns have been burnt. We cannot now expect happiness under the domination of Great Britain. All former attachments have been obliterated." Howe was gentlemanly and the three left.

Howe felt deflated and wrote Germain that the colonies were not going to accede to any peace or alliance - but only as free and independent states.

In the meantime, Washington's troops voted to evacuate New York City and then retracting to Harlem Heights and going further to the high ground at Fort Washington. Washington ordered the town stripped and this retreat ended with the Battle of Kip's Bay and Harlem Heights.

Left behind in a rush were over half of Washington's heavy artillery- 64 guns - including 15 mounted 32 pounders and twelve thousand round shot - enough to replenish the dwindling British naval ammunition stocks.

Washington had lost another battle, most of another island and his first city. This was a rout and 50 were killed and 371 captured. New York burned.

August 1776: Council of War in the house of Mr Philip Livingstone in Brooklyn, after the Battle of Long Island. (Photo by Three Lions/Getty Images)

15. A FIGHT AMONG WOLVES

New York,

July–August 1776

George Washington returned from Philadelphia and wanted every soldier in his command to hear the declaration. His hope was that this declaration would transform his army because they now would have an ambitious and righteous cause to fight for.

The Declaration of Independence was read - a document written by Thomas Jefferson who wrote that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, and that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Jefferson claimed later that this was intended to be an expression of the American mind.

A third of the delegates who would sign the Declaration were slave owners and Jefferson had two hundred - so you can see due to their culture - there was a disconnect. But as Edmund S. Morgan would write: "The creed of equality did not give men equality, but invited them to claim it, invited them, not to know their place and keep it, but to seek and demand a better place." This chapter is quite timely in terms of current events.

After the decapitation of the George III statue, General Howe had an answer to the Declaration of Independence, and he sent it on Friday afternoon, July 12th. Washington tried to figure out what would be the Howe brothers next move - would the British continue to push up the Hudson, perhaps in hopes of joining Carleton's force from Canada or would they thread the East River to Long Island Sound, landing behind the American fortifications in New York?

Or would they launch amphibious landings on both Manhattan and Long Island?

In the end, Washington misjudged the strategy of the British and Howe chose the Battle of Long Island.

16. A SENTIMENTAL MANNER OF MAKING WAR

New York

September 1776

Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge were called to a conference with Lord Howe in Staten Island. Howe wanted to discuss putting a stop to the calamities of war.

Franklin retorted that "Forces have been sent out and towns have been burnt. We cannot now expect happiness under the domination of Great Britain. All former attachments have been obliterated." Howe was gentlemanly and the three left.

Howe felt deflated and wrote Germain that the colonies were not going to accede to any peace or alliance - but only as free and independent states.

In the meantime, Washington's troops voted to evacuate New York City and then retracting to Harlem Heights and going further to the high ground at Fort Washington. Washington ordered the town stripped and this retreat ended with the Battle of Kip's Bay and Harlem Heights.

Left behind in a rush were over half of Washington's heavy artillery- 64 guns - including 15 mounted 32 pounders and twelve thousand round shot - enough to replenish the dwindling British naval ammunition stocks.

Washington had lost another battle, most of another island and his first city. This was a rout and 50 were killed and 371 captured. New York burned.

The Declaration of Independence

IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. — Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences:

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. — And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

New Hampshire:

Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton

Massachusetts:

John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island:

Stephen Hopkins, William Ellery

Connecticut:

Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott

New York:

William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris

New Jersey:

Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark

Pennsylvania:

Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross

Delaware:

Caesar Rodney, George Read, Thomas McKean

Maryland:

Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Virginia:

George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson, Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton

North Carolina:

William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn

South Carolina:

Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward, Jr., Thomas Lynch, Jr., Arthur Middleton

Georgia:

Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton

Source: USHistory.org

IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. — Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences:

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. — And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

New Hampshire:

Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton

Massachusetts:

John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island:

Stephen Hopkins, William Ellery

Connecticut:

Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott

New York:

William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris

New Jersey:

Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark

Pennsylvania:

Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross

Delaware:

Caesar Rodney, George Read, Thomas McKean

Maryland:

Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Virginia:

George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson, Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton

North Carolina:

William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn

South Carolina:

Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward, Jr., Thomas Lynch, Jr., Arthur Middleton

Georgia:

Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton

Source: USHistory.org

Psalm 80 - KIng James Bible Version

To the chief Musician upon ShoshannimEduth, A Psalm of Asaph.

Give ear, O Shepherd of Israel, thou that leadest Joseph like a flock; thou that dwellest between the cherubims, shine forth.

Before Ephraim and Benjamin and Manasseh stir up thy strength, and come and save us.

Turn us again, O God, and cause thy face to shine; and we shall be saved.

O LORD God of hosts, how long wilt thou be angry against the prayer of thy people?

Thou feedest them with the bread of tears; and givest them tears to drink in great measure.

Thou makest us a strife unto our neighbours: and our enemies laugh among themselves.

Turn us again, O God of hosts, and cause thy face to shine; and we shall be saved.

Thou hast brought a vine out of Egypt: thou hast cast out the heathen, and planted it.

Thou preparedst room before it, and didst cause it to take deep root, and it filled the land.

The hills were covered with the shadow of it, and the boughs thereof were like the goodly cedars.

She sent out her boughs unto the sea, and her branches unto the river.

Why hast thou then broken down her hedges, so that all they which pass by the way do pluck her?

The boar out of the wood doth waste it, and the wild beast of the field doth devour it.

Return, we beseech thee, O God of hosts: look down from heaven, and behold, and visit this vine;

And the vineyard which thy right hand hath planted, and the branch that thou madest strong for thyself.

It is burned with fire, it is cut down: they perish at the rebuke of thy countenance.

Let thy hand be upon the man of thy right hand, upon the son of man whom thou madest strong for thyself.

So will not we go back from thee: quicken us, and we will call upon thy name.

Turn us again, O LORD God of hosts, cause thy face to shine; and we shall be saved.

To the chief Musician upon ShoshannimEduth, A Psalm of Asaph.

Give ear, O Shepherd of Israel, thou that leadest Joseph like a flock; thou that dwellest between the cherubims, shine forth.

Before Ephraim and Benjamin and Manasseh stir up thy strength, and come and save us.

Turn us again, O God, and cause thy face to shine; and we shall be saved.

O LORD God of hosts, how long wilt thou be angry against the prayer of thy people?

Thou feedest them with the bread of tears; and givest them tears to drink in great measure.

Thou makest us a strife unto our neighbours: and our enemies laugh among themselves.

Turn us again, O God of hosts, and cause thy face to shine; and we shall be saved.

Thou hast brought a vine out of Egypt: thou hast cast out the heathen, and planted it.

Thou preparedst room before it, and didst cause it to take deep root, and it filled the land.

The hills were covered with the shadow of it, and the boughs thereof were like the goodly cedars.

She sent out her boughs unto the sea, and her branches unto the river.

Why hast thou then broken down her hedges, so that all they which pass by the way do pluck her?

The boar out of the wood doth waste it, and the wild beast of the field doth devour it.

Return, we beseech thee, O God of hosts: look down from heaven, and behold, and visit this vine;

And the vineyard which thy right hand hath planted, and the branch that thou madest strong for thyself.

It is burned with fire, it is cut down: they perish at the rebuke of thy countenance.

Let thy hand be upon the man of thy right hand, upon the son of man whom thou madest strong for thyself.

So will not we go back from thee: quicken us, and we will call upon thy name.

Turn us again, O LORD God of hosts, cause thy face to shine; and we shall be saved.

message 8:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 22, 2020 04:41AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Pulling Down the Statue of George III by the "Sons of Freedom"

Stirred up after hearing the Declaration of Independence read publicly on July 9, 1776, the so-called Sons of Freedom—a mix of George Washington's soldiers and civilians—tear down a statue of the British monarch George III in New York City.

The lead statue was later moved to Connecticut and used to make guns and bullets.

This engraving, based roughly on a painting created about 1859, shows a mix of white men, women, and children of varying social classes, as well as an Indian in headdress carrying a spear (at left).

In contrast, a contemporary print of the event made in Europe in 1776 portrayed a group of free blacks or slaves helping to topple the statue.

The equestrian statue had originally been erected in Bowling Green, a public park in lower Manhattan, in the wake of the king's help in repealing the hated Stamp Act of 1765.

Original Author: John C. McRae, engraver; based on a painting by Johannes A. Oertel - Created: Engraving ca. 1875; painting ca. 1859 - Medium: Engraving

Source: Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

message 9:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 22, 2020 05:19AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

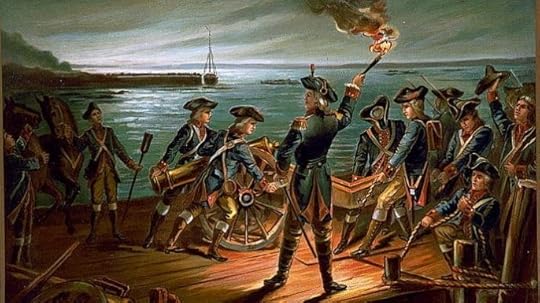

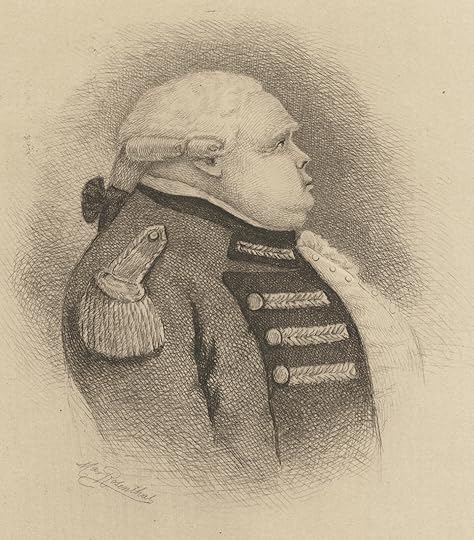

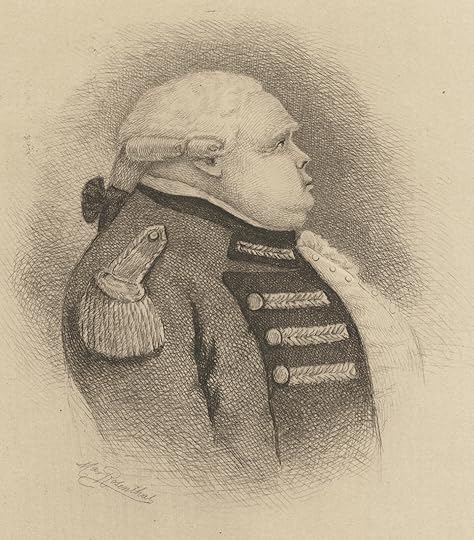

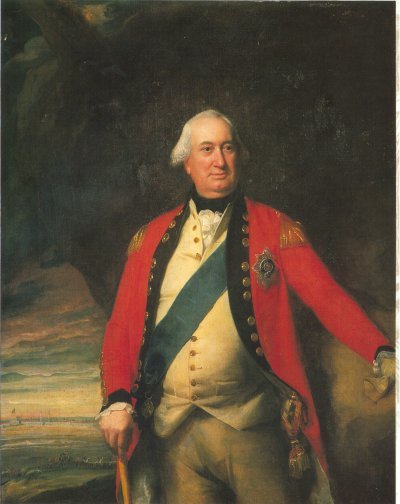

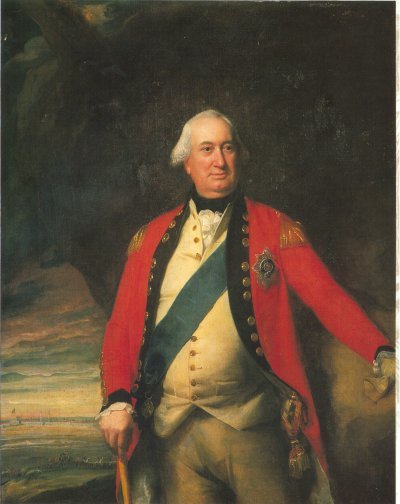

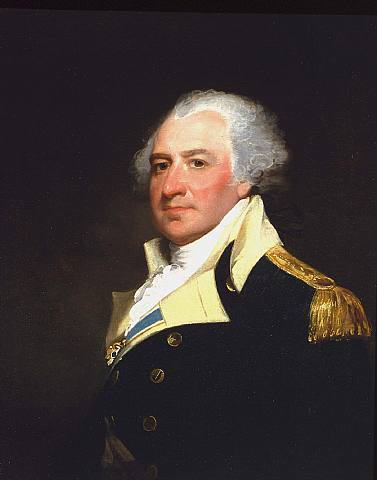

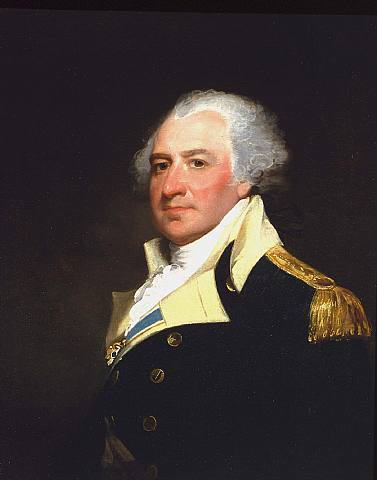

General Howe is back off the Coast of Staten Island and curling along the lower lip of Manhattan opening fire at 4:05PM.

Atkinson wrote: "General Howe had an answer to the Declaration of Independence, and he sent it on Friday afternoon, July 12!

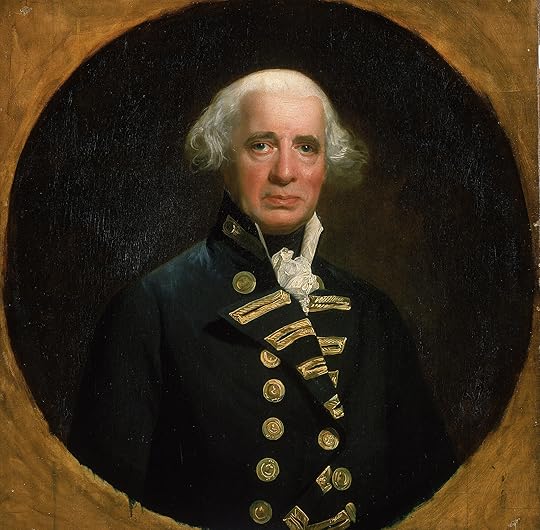

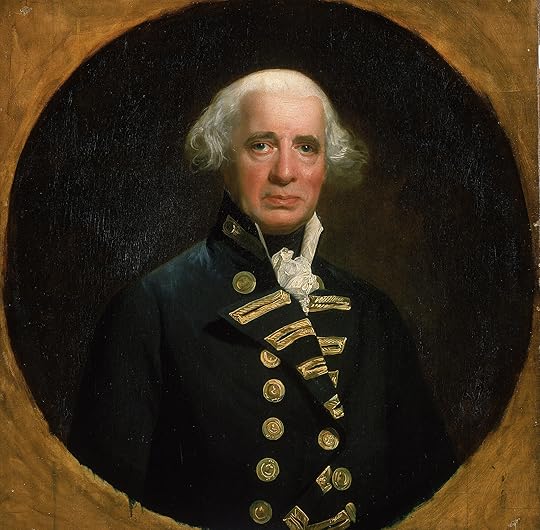

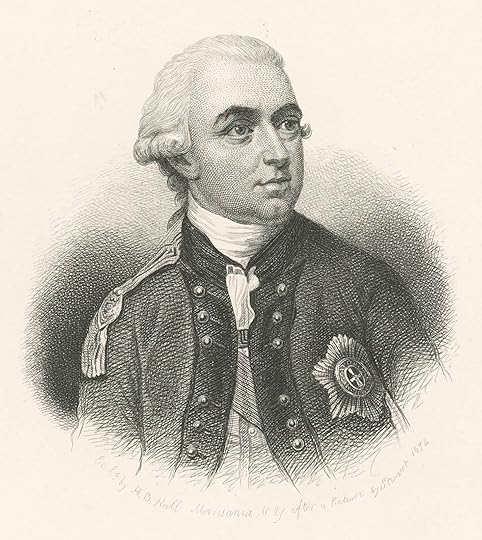

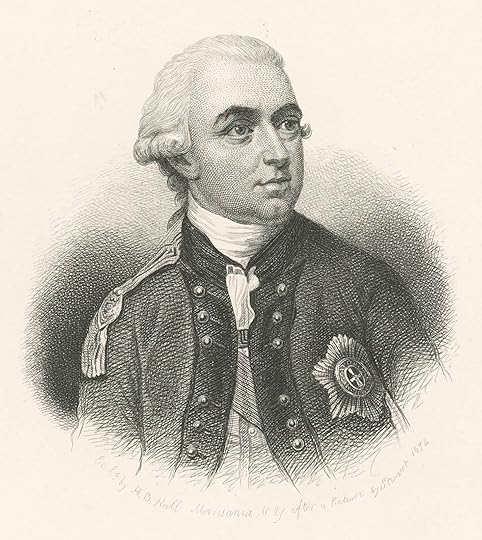

General William Howe

This is a color mezzotint of British General Sir William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, active in the American Revolutionary War at Brown University

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, KB, PC (10 August 1729 – 12 July 1814) was a British Army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British land forces in the Colonies during the American War of Independence. Howe was one of three brothers who had distinguished military careers. In historiography of the American war he is usually referred to as Sir William Howe to distinguish his brother Richard, who was 4th Viscount Howe at that time.

Having joined the army in 1746, Howe saw extensive service in the War of the Austrian Succession and Seven Years' War. He became known for his role in the capture of Quebec in 1759 when he led a British force to capture the cliffs at Anse-au-Foulon, allowing James Wolfe to land his army and engage the French in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Howe also participated in the campaigns to take Louisbourg, Belle Île and Havana.

He was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the Isle of Wight, a post he held until 1795.

Howe was sent to North America in March 1775, arriving in May after the American War of Independence broke out. After leading British troops to a costly victory in the Battle of Bunker Hill, Howe took command of all British forces in America from Thomas Gage in September of that year. Howe's record in North America was marked by the successful capture of both New York City and Philadelphia. However, poor British campaign planning for 1777 contributed to the failure of John Burgoyne's Saratoga campaign, which played a major role in the entry of France into the war. Howe's role in developing those plans and the degree to which he was responsible for British failures that year (despite his personal success at Philadelphia) have both been subjects of contemporary and historic debate.

He was knighted after his successes in 1776. He resigned his post as Commander-in-Chief, British land forces in America, in 1777, and the next year returned to England, where he was at times active in the defence of the British Isles. He sat in the House of Commons from 1758 to 1780 for Nottingham. He inherited the Viscountcy of Howe upon the death of his brother Richard in 1799. He married, but had no children, and the viscountcy became extinct with his death in 1814."

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William...

More:

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_E...

General Howe's Orderly Book

https://archive.org/details/generalsi...

From the American Battlefield Trust:

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/bi...

The Enigma of General Howe:

https://www.americanheritage.com/enig...

He did not want to fight the Americans because they were British but was called to serve his King.

Letter from George Washington to General Howe

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

The Conquerors: William Howe - Conqueror of New York

Video Link (quite good): https://youtu.be/0zM5y3grWJo

Bunker Hill was a devastating blow to Howe - even though he won the hill (Breeds Hill) he lost over 40% of his forces doing so.

The Brown Bess - musket of choice for British during RW

Revolutionary War Brown Bess Flintlock Musket – Tower Short Land Pattern Brown Bess with Bayonet

After surviving the bloodletting at Bunker Hill, Major General William Howe took command of all British forces in America, overseeing both the evacuation of Boston and the attack on New York. Famously taciturn, he “never wastes a monosyllable,” one wit quipped.

by William Howe (no photo)

by William Howe (no photo)

by Joseph Galloway (no photo)

by Joseph Galloway (no photo)

by Barnet Schecter (no photo)

by Barnet Schecter (no photo)

by Edwin G. Burrows (no photo)

by Edwin G. Burrows (no photo)

Sources: Wikipedia, Brown University, Encyclopedia Britannica, Internet Archive, The American Battlefield Trust, American Heritage, Founders on Line - General Archives, Youtube, Encyclopedia of Virginia, Worthington Galleries, History Channel

Atkinson wrote: "General Howe had an answer to the Declaration of Independence, and he sent it on Friday afternoon, July 12!

General William Howe

This is a color mezzotint of British General Sir William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, active in the American Revolutionary War at Brown University

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, KB, PC (10 August 1729 – 12 July 1814) was a British Army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British land forces in the Colonies during the American War of Independence. Howe was one of three brothers who had distinguished military careers. In historiography of the American war he is usually referred to as Sir William Howe to distinguish his brother Richard, who was 4th Viscount Howe at that time.

Having joined the army in 1746, Howe saw extensive service in the War of the Austrian Succession and Seven Years' War. He became known for his role in the capture of Quebec in 1759 when he led a British force to capture the cliffs at Anse-au-Foulon, allowing James Wolfe to land his army and engage the French in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Howe also participated in the campaigns to take Louisbourg, Belle Île and Havana.

He was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the Isle of Wight, a post he held until 1795.

Howe was sent to North America in March 1775, arriving in May after the American War of Independence broke out. After leading British troops to a costly victory in the Battle of Bunker Hill, Howe took command of all British forces in America from Thomas Gage in September of that year. Howe's record in North America was marked by the successful capture of both New York City and Philadelphia. However, poor British campaign planning for 1777 contributed to the failure of John Burgoyne's Saratoga campaign, which played a major role in the entry of France into the war. Howe's role in developing those plans and the degree to which he was responsible for British failures that year (despite his personal success at Philadelphia) have both been subjects of contemporary and historic debate.

He was knighted after his successes in 1776. He resigned his post as Commander-in-Chief, British land forces in America, in 1777, and the next year returned to England, where he was at times active in the defence of the British Isles. He sat in the House of Commons from 1758 to 1780 for Nottingham. He inherited the Viscountcy of Howe upon the death of his brother Richard in 1799. He married, but had no children, and the viscountcy became extinct with his death in 1814."

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William...

More:

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_E...

General Howe's Orderly Book

https://archive.org/details/generalsi...

From the American Battlefield Trust:

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/bi...

The Enigma of General Howe:

https://www.americanheritage.com/enig...

He did not want to fight the Americans because they were British but was called to serve his King.

Letter from George Washington to General Howe

https://founders.archives.gov/documen...

The Conquerors: William Howe - Conqueror of New York

Video Link (quite good): https://youtu.be/0zM5y3grWJo

Bunker Hill was a devastating blow to Howe - even though he won the hill (Breeds Hill) he lost over 40% of his forces doing so.

The Brown Bess - musket of choice for British during RW

Revolutionary War Brown Bess Flintlock Musket – Tower Short Land Pattern Brown Bess with Bayonet

After surviving the bloodletting at Bunker Hill, Major General William Howe took command of all British forces in America, overseeing both the evacuation of Boston and the attack on New York. Famously taciturn, he “never wastes a monosyllable,” one wit quipped.

by William Howe (no photo)

by William Howe (no photo) by Joseph Galloway (no photo)

by Joseph Galloway (no photo) by Barnet Schecter (no photo)

by Barnet Schecter (no photo) by Edwin G. Burrows (no photo)

by Edwin G. Burrows (no photo)Sources: Wikipedia, Brown University, Encyclopedia Britannica, Internet Archive, The American Battlefield Trust, American Heritage, Founders on Line - General Archives, Youtube, Encyclopedia of Virginia, Worthington Galleries, History Channel

message 10:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 22, 2020 03:13PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

The Battle of Long Island

Animated version of the battle

Link: https://youtu.be/kiMS09xI1GI

Liberty - Battle of Long Island PBS

Link: https://youtu.be/LdPI6T1kqD0

Source: The Armchair Historian, Youtube, PBS

More:

by

by

Jeremy Black

Jeremy Black

by Nicholas A.M. Rodger (no photo)

by Nicholas A.M. Rodger (no photo)

by

by

Pauline Maier

Pauline Maier

by

by

Pauline Maier

Pauline Maier

by

by

Pauline Maier

Pauline Maier

by George C. Neumann (no photo)

by George C. Neumann (no photo)

byGeorge C. Neumann (no photo)

byGeorge C. Neumann (no photo)

Animated version of the battle

Link: https://youtu.be/kiMS09xI1GI

Liberty - Battle of Long Island PBS

Link: https://youtu.be/LdPI6T1kqD0

Source: The Armchair Historian, Youtube, PBS

More:

by

by

Jeremy Black

Jeremy Black by Nicholas A.M. Rodger (no photo)

by Nicholas A.M. Rodger (no photo) by

by

Pauline Maier

Pauline Maier by

by

Pauline Maier

Pauline Maier by

by

Pauline Maier

Pauline Maier by George C. Neumann (no photo)

by George C. Neumann (no photo) byGeorge C. Neumann (no photo)

byGeorge C. Neumann (no photo)

message 11:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 22, 2020 01:29PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

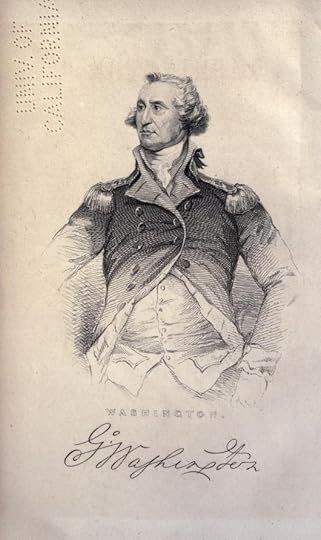

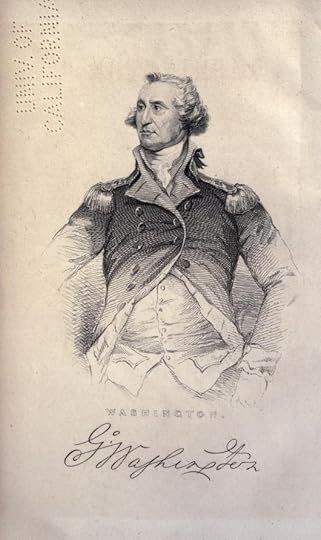

George Washington's Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation

"By age sixteen, Washington had copied out by hand, 110 Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.

They are based on a set of rules composed by French Jesuits in 1595. Presumably they were copied out as part of an exercise in penmanship assigned by young Washington's schoolmaster.

The first English translation of the French rules appeared in 1640, and are ascribed to Francis Hawkins the twelve-year-old son of a doctor.

Today many, if not all of these rules, sound a little fussy if not downright silly. It would be easy to dismiss them as outdated and appropriate to a time of powdered wigs and quills, but they reflect a focus that is increasingly difficult to find.

The rules have in common a focus on other people rather than the narrow focus of our own self-interests that we find so prevalent today. Fussy or not, they represent more than just manners. They are the small sacrifices that we should all be willing to make for the good of all and the sake of living together.

These rules proclaim our respect for others and in turn give us the gift of self-respect and heightened self-esteem.

Richard Brookhiser, in his book on Washington wrote that "all modern manners in the western world were originally aristocratic.

Courtesy meant behavior appropriate to a court; chivalry comes from chevalier – a knight.

Yet Washington was to dedicate himself to freeing America from a court's control. Could manners survive the operation? Without realizing it, the Jesuits who wrote them, and the young man who copied them, were outlining and absorbing a system of courtesy appropriate to equals and near-equals.

When the company for whom the decent behavior was to be performed expanded to the nation, Washington was ready. Parson Weems got this right, when he wrote that it was 'no wonder every body honoured him who honoured every body.'"

The Rules:

1st Every Action done in Company, ought to be with Some Sign of Respect, to those that are Present.

2nd When in Company, put not your Hands to any Part of the Body, not usually Discovered. Be considerate of others. Do not embarrass others.

3rd Show Nothing to your Friend that may affright him.

4th In the Presence of Others Sing not to yourself with a humming Noise, nor Drum with your Fingers or Feet.

5th If You Cough, Sneeze, Sigh, or Yawn, do it not Loud but Privately; and Speak not in your Yawning, but put Your handkerchief or Hand before your face and turn aside.

6th Sleep not when others Speak, Sit not when others stand, Speak not when you Should hold your Peace, walk not on when others Stop.

7th Put not off your Cloths in the presence of Others, nor go out your Chamber half Dressed.

8th At Play and at Fire its Good manners to Give Place to the last Commer, and affect not to Speak Louder than Ordinary.

9th Spit not in the Fire, nor Stoop low before it neither Put your Hands into the Flames to warm them, nor Set your Feet upon the Fire especially if there be meat before it.

10th When you Sit down, Keep your Feet firm and Even, without putting one on the other or Crossing them.

11th Shift not yourself in the Sight of others nor Gnaw your nails.

12th Shake not the head, Feet, or Legs roll not the Eyes lift not one eyebrow higher than the other wry not the mouth, and bedew no mans face with your Spittle, by approaching too near him when you Speak.

13th Kill no Vermin as Fleas, lice ticks &c in the Sight of Others, if you See any filth or thick Spittle put your foot Dexterously upon it if it be upon the Cloths of your Companions, Put it off privately, and if it be upon your own Cloths return Thanks to him who puts it off.

14th Turn not your Back to others especially in Speaking, Jog not the Table or Desk on which Another reads or writes, lean not upon any one.

15th Keep your Nails clean and Short, also your Hands and Teeth Clean yet without Showing any great Concern for them.

16th Do not Puff up the Cheeks, Loll not out the tongue rub the Hands, or beard, thrust out the lips, or bite them or keep the Lips too open or too Close.

17th Be no Flatterer, neither Play with any that delights not to be Play'd Withal.

18th Read no Letters, Books, or Papers in Company but when there is a Necessity for the doing of it you must ask leave: come not near the Books or Writings of Another so as to read them unless desired or give your opinion of them unasked also look not nigh when another is writing a Letter.

19th Let your Countenance be pleasant but in Serious Matters Somewhat grave.

20th The Gestures of the Body must be Suited to the discourse you are upon.

21st Reproach none for the Infirmities of Nature, nor Delight to Put them that have in mind thereof.

22nd Show not yourself glad at the Misfortune of another though he were your enemy.

23rd When you see a Crime punished, you may be inwardly Pleased; but always show Pity to the Suffering Offender.

Don't draw attention to yourself.

24th Do not laugh too loud or too much at any Public Spectacle.

25th Superfluous Complements and all Affectation of Ceremony are to be avoided, yet where due they are not to be Neglected.

26th In Pulling off your Hat to Persons of Distinction, as Noblemen, Justices, Churchmen &c make a Reverence, bowing more or less according to the Custom of the Better Bred, and Quality of the Person. Amongst your equals expect not always that they Should begin with you first, but to Pull off the Hat when there is no need is Affectation, in the Manner of Saluting and resaluting in words keep to the most usual Custom.

27th Tis ill manners to bid one more eminent than yourself be covered as well as not to do it to whom it's due Likewise he that makes too much haste to Put on his hat does not well, yet he ought to Put it on at the first, or at most the Second time of being asked; now what is herein Spoken, of Qualification in behavior in Saluting, ought also to be observed in taking of Place, and Sitting down for ceremonies without Bounds is troublesome.

28th If any one come to Speak to you while you are are Sitting Stand up though he be your Inferior, and when you Present Seats let it be to every one according to his Degree.

29th When you meet with one of Greater Quality than yourself, Stop, and retire especially if it be at a Door or any Straight place to give way for him to Pass.

30th In walking the highest Place in most Countries Seems to be on the right hand therefore Place yourself on the left of him whom you desire to Honor: but if three walk together the middest Place is the most Honorable the wall is usually given to the most worthy if two walk together.

31st If any one far Surpasses others, either in age, Estate, or Merit yet would give Place to a meaner than himself in his own lodging or elsewhere the one ought not to except it, So he on the other part should not use much earnestness nor offer it above once or twice.

32nd To one that is your equal, or not much inferior you are to give the chief Place in your Lodging and he to who 'is offered ought at the first to refuse it but at the Second to accept though not without acknowledging his own unworthiness.

33rd They that are in Dignity or in office have in all places Precedency but whilst they are Young they ought to respect those that are their equals in Birth or other Qualities, though they have no Public charge.

34th It is good Manners to prefer them to whom we Speak before ourselves especially if they be above us with whom in no Sort we ought to begin. When you speak, be concise.

35th Let your Discourse with Men of Business be Short and Comprehensive.

36th Artificers & Persons of low Degree ought not to use many ceremonies to Lords, or Others of high Degree but Respect and highly Honor them, and those of high Degree ought to treat them with affability & Courtesy, without Arrogance.

37th In speaking to men of Quality do not lean nor Look them full in the Face, nor approach too near them at lest Keep a full Pace from them.

38th In visiting the Sick, do not Presently play the Physician if you be not Knowing therein.

39th In writing or Speaking, give to every Person his due Title According to his Degree & the Custom of the Place. Do not argue with your superior. Submit your ideas with humility.

40th Strive not with your Superiors in argument, but always Submit your Judgment to others with Modesty.

41st Undertake not to Teach your equal in the art himself Professes; it Savours of arrogance.

42nd Let thy ceremonies in Courtesy be proper to the Dignity of his place with whom thou converses for it is absurd to act the same with a Clown and a Prince.

43rd Do not express Joy before one sick or in pain for that contrary Passion will aggravate his Misery. When a person does their best and fails, do not criticize him.

44th When a man does all he can though it Succeeds not well blame not him that did it. When you must give advice or criticism, consider the timing, whether it should be given in public or private, the manner and above all be gentle."

Source: Foundations Magazine (continued in next post)

"By age sixteen, Washington had copied out by hand, 110 Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.

They are based on a set of rules composed by French Jesuits in 1595. Presumably they were copied out as part of an exercise in penmanship assigned by young Washington's schoolmaster.

The first English translation of the French rules appeared in 1640, and are ascribed to Francis Hawkins the twelve-year-old son of a doctor.

Today many, if not all of these rules, sound a little fussy if not downright silly. It would be easy to dismiss them as outdated and appropriate to a time of powdered wigs and quills, but they reflect a focus that is increasingly difficult to find.

The rules have in common a focus on other people rather than the narrow focus of our own self-interests that we find so prevalent today. Fussy or not, they represent more than just manners. They are the small sacrifices that we should all be willing to make for the good of all and the sake of living together.

These rules proclaim our respect for others and in turn give us the gift of self-respect and heightened self-esteem.

Richard Brookhiser, in his book on Washington wrote that "all modern manners in the western world were originally aristocratic.

Courtesy meant behavior appropriate to a court; chivalry comes from chevalier – a knight.

Yet Washington was to dedicate himself to freeing America from a court's control. Could manners survive the operation? Without realizing it, the Jesuits who wrote them, and the young man who copied them, were outlining and absorbing a system of courtesy appropriate to equals and near-equals.

When the company for whom the decent behavior was to be performed expanded to the nation, Washington was ready. Parson Weems got this right, when he wrote that it was 'no wonder every body honoured him who honoured every body.'"

The Rules:

1st Every Action done in Company, ought to be with Some Sign of Respect, to those that are Present.

2nd When in Company, put not your Hands to any Part of the Body, not usually Discovered. Be considerate of others. Do not embarrass others.

3rd Show Nothing to your Friend that may affright him.

4th In the Presence of Others Sing not to yourself with a humming Noise, nor Drum with your Fingers or Feet.

5th If You Cough, Sneeze, Sigh, or Yawn, do it not Loud but Privately; and Speak not in your Yawning, but put Your handkerchief or Hand before your face and turn aside.

6th Sleep not when others Speak, Sit not when others stand, Speak not when you Should hold your Peace, walk not on when others Stop.

7th Put not off your Cloths in the presence of Others, nor go out your Chamber half Dressed.

8th At Play and at Fire its Good manners to Give Place to the last Commer, and affect not to Speak Louder than Ordinary.

9th Spit not in the Fire, nor Stoop low before it neither Put your Hands into the Flames to warm them, nor Set your Feet upon the Fire especially if there be meat before it.

10th When you Sit down, Keep your Feet firm and Even, without putting one on the other or Crossing them.

11th Shift not yourself in the Sight of others nor Gnaw your nails.

12th Shake not the head, Feet, or Legs roll not the Eyes lift not one eyebrow higher than the other wry not the mouth, and bedew no mans face with your Spittle, by approaching too near him when you Speak.

13th Kill no Vermin as Fleas, lice ticks &c in the Sight of Others, if you See any filth or thick Spittle put your foot Dexterously upon it if it be upon the Cloths of your Companions, Put it off privately, and if it be upon your own Cloths return Thanks to him who puts it off.

14th Turn not your Back to others especially in Speaking, Jog not the Table or Desk on which Another reads or writes, lean not upon any one.

15th Keep your Nails clean and Short, also your Hands and Teeth Clean yet without Showing any great Concern for them.

16th Do not Puff up the Cheeks, Loll not out the tongue rub the Hands, or beard, thrust out the lips, or bite them or keep the Lips too open or too Close.

17th Be no Flatterer, neither Play with any that delights not to be Play'd Withal.

18th Read no Letters, Books, or Papers in Company but when there is a Necessity for the doing of it you must ask leave: come not near the Books or Writings of Another so as to read them unless desired or give your opinion of them unasked also look not nigh when another is writing a Letter.

19th Let your Countenance be pleasant but in Serious Matters Somewhat grave.

20th The Gestures of the Body must be Suited to the discourse you are upon.

21st Reproach none for the Infirmities of Nature, nor Delight to Put them that have in mind thereof.

22nd Show not yourself glad at the Misfortune of another though he were your enemy.

23rd When you see a Crime punished, you may be inwardly Pleased; but always show Pity to the Suffering Offender.

Don't draw attention to yourself.

24th Do not laugh too loud or too much at any Public Spectacle.

25th Superfluous Complements and all Affectation of Ceremony are to be avoided, yet where due they are not to be Neglected.

26th In Pulling off your Hat to Persons of Distinction, as Noblemen, Justices, Churchmen &c make a Reverence, bowing more or less according to the Custom of the Better Bred, and Quality of the Person. Amongst your equals expect not always that they Should begin with you first, but to Pull off the Hat when there is no need is Affectation, in the Manner of Saluting and resaluting in words keep to the most usual Custom.

27th Tis ill manners to bid one more eminent than yourself be covered as well as not to do it to whom it's due Likewise he that makes too much haste to Put on his hat does not well, yet he ought to Put it on at the first, or at most the Second time of being asked; now what is herein Spoken, of Qualification in behavior in Saluting, ought also to be observed in taking of Place, and Sitting down for ceremonies without Bounds is troublesome.

28th If any one come to Speak to you while you are are Sitting Stand up though he be your Inferior, and when you Present Seats let it be to every one according to his Degree.

29th When you meet with one of Greater Quality than yourself, Stop, and retire especially if it be at a Door or any Straight place to give way for him to Pass.

30th In walking the highest Place in most Countries Seems to be on the right hand therefore Place yourself on the left of him whom you desire to Honor: but if three walk together the middest Place is the most Honorable the wall is usually given to the most worthy if two walk together.