Victorians! discussion

This topic is about

Villette

Archived Group Reads 2022

>

Villette: Week 4: Chapter XVI-XX

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Secrets/Recognition/Old Friends

Lucy we see has been keeping a secret from us, for she recognized Dr John as being Graham Bretton quite early on, but did not let the reader know. Dr John on the other hand, perhaps too absorbed in Ginevra, didn’t recognize Lucy, but once he brings her home, and Mrs Bretton recognizes her, their old acquaintance is renewed and the life Lucy has been leading in Villette changes.

What did you think of the way Lucy revealed the truth here? (In her defence, we did know his name was John Graham Bretton, so ought we to have guessed? Did we?)

Lucy we see has been keeping a secret from us, for she recognized Dr John as being Graham Bretton quite early on, but did not let the reader know. Dr John on the other hand, perhaps too absorbed in Ginevra, didn’t recognize Lucy, but once he brings her home, and Mrs Bretton recognizes her, their old acquaintance is renewed and the life Lucy has been leading in Villette changes.

What did you think of the way Lucy revealed the truth here? (In her defence, we did know his name was John Graham Bretton, so ought we to have guessed? Did we?)

Lucy and John/Graham

Once the truth is revealed, and after a brief quarrel over Ginevra, Lucy and John develop a comfortable friendship, able to converse on all subjects, and he also begins to show her around town. What did we think of this friendship? Especially as against, how things were earlier between them—back at Bretton, and then again at the Pensionnat.

Lucy also tells us that she used to stare at his portrait back in Bretton, and we find her doing that at the Pensionnat as well. Do her feelings for him run deeper than she is letting on? I think some of us already thought that, but is this confirmation?

Once the truth is revealed, and after a brief quarrel over Ginevra, Lucy and John develop a comfortable friendship, able to converse on all subjects, and he also begins to show her around town. What did we think of this friendship? Especially as against, how things were earlier between them—back at Bretton, and then again at the Pensionnat.

Lucy also tells us that she used to stare at his portrait back in Bretton, and we find her doing that at the Pensionnat as well. Do her feelings for him run deeper than she is letting on? I think some of us already thought that, but is this confirmation?

Graham and Ginevra

Graham is quite clearly smitten by Ginevra, not willing to see sense, even when Lucy tries to point it out, but at the concert, Ginevra takes things to far by making fun of poor Mrs Bretton to her companion Lady Sara (who we incidentally learn would probably not approve). Now Graham seems able to see her true nature, perhaps worse, for from a point where he saw no ill in her, he is now seeing only ill—from her avarice to her flirtatiousness. Is the truth somewhere in between as Lucy seems to assert (whether she thinks so, we can’t say) or is Graham’s current view the right one?

Graham is quite clearly smitten by Ginevra, not willing to see sense, even when Lucy tries to point it out, but at the concert, Ginevra takes things to far by making fun of poor Mrs Bretton to her companion Lady Sara (who we incidentally learn would probably not approve). Now Graham seems able to see her true nature, perhaps worse, for from a point where he saw no ill in her, he is now seeing only ill—from her avarice to her flirtatiousness. Is the truth somewhere in between as Lucy seems to assert (whether she thinks so, we can’t say) or is Graham’s current view the right one?

message 5:

by

Lady Clementina, Moderator

(last edited May 01, 2022 03:55AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Morals/Propriety—a Reversal?

Morality and propriety were themes that came up this week as well but it would seem in reverse to previous experiences for while earlier we had Lucy disapproving of the more of those at Villette, including Madame Beck, now M. Paul seems to disapprove of Lucy’s behavior—from being at an art gallery unattended and looking at a painting that he certainly considers inappropriate. Then again, his disapproval at the concert.

Morality and propriety were themes that came up this week as well but it would seem in reverse to previous experiences for while earlier we had Lucy disapproving of the more of those at Villette, including Madame Beck, now M. Paul seems to disapprove of Lucy’s behavior—from being at an art gallery unattended and looking at a painting that he certainly considers inappropriate. Then again, his disapproval at the concert.

Lucy and M Paul

And which brings us to the exchanges between Lucy and Mr Paul this week. Be it his disapproval at the gallery or his anger at the concert—what did we make of this? And he seems concerned over her health, and how she was when alone at the Pensionnat. Is it simply dissatisfaction at what he thinks is inappropriate behaviour of a colleague, or something more?

And which brings us to the exchanges between Lucy and Mr Paul this week. Be it his disapproval at the gallery or his anger at the concert—what did we make of this? And he seems concerned over her health, and how she was when alone at the Pensionnat. Is it simply dissatisfaction at what he thinks is inappropriate behaviour of a colleague, or something more?

I admit I feel a bit cheated by this reveal. Lucy has chosen deliberately to conceal from us something she knew. I remember thinking when she met the stranger with long red hair who helped her locate her trunk and guided her across the park that he must soon be revealed to be Graham; but then he was reintroduced under another name, and Lucy said nothing about it, so I accepted the novel wasn't going in this direction. And then it did, after all! I don't remember his being referred to by his full name anywhere upon his reintroduction as Dr John (perhaps I overlooked it). It's unfortunately hard for me to look back on the Kindle, especially as this is the worst-formatted eBook I've yet encountered. Anyway, just wanted to vent. C.B. deceived us!

I admit I feel a bit cheated by this reveal. Lucy has chosen deliberately to conceal from us something she knew. I remember thinking when she met the stranger with long red hair who helped her locate her trunk and guided her across the park that he must soon be revealed to be Graham; but then he was reintroduced under another name, and Lucy said nothing about it, so I accepted the novel wasn't going in this direction. And then it did, after all! I don't remember his being referred to by his full name anywhere upon his reintroduction as Dr John (perhaps I overlooked it). It's unfortunately hard for me to look back on the Kindle, especially as this is the worst-formatted eBook I've yet encountered. Anyway, just wanted to vent. C.B. deceived us!

Historical note: the King would have been Leopold I, and his forlorn-looking son, Leopold II, a strange man now infamous for his brutal colonization of what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Historical note: the King would have been Leopold I, and his forlorn-looking son, Leopold II, a strange man now infamous for his brutal colonization of what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

M. Paul Emanuel has very strict, Catholic views on propriety, which I believehe would apply to any demoiselle. He strikes me as misogynistic. (But maybe this is redundant.)

M. Paul Emanuel has very strict, Catholic views on propriety, which I believehe would apply to any demoiselle. He strikes me as misogynistic. (But maybe this is redundant.)He doesn't seem to think much of Lucy and her depressive, neurotic ways. I'm not sure how this guy is supposed to be likeable in any way.

Something that really stood out to me in these chapters is a theme also explored in _Shirley_: the power of money. Lucy is typically isolated because all she has is this job in a school, without really much money to afford any kind of social interaction. Some of this is because of the type of jobs available to women at the time (no education or positions as highly-paid doctors for women). This period of joy and lifting of depression in company and in fun outings is only achievable with a certain level of financial comfort, which she is borrowing/temporarily enjoying at the Brettons' expense. Despite Père Silas' and M. Emanuel's faith in the power of good works, C.B. shows us that a person does need some society and positive experiences to lift oneself out of depression.

Something that really stood out to me in these chapters is a theme also explored in _Shirley_: the power of money. Lucy is typically isolated because all she has is this job in a school, without really much money to afford any kind of social interaction. Some of this is because of the type of jobs available to women at the time (no education or positions as highly-paid doctors for women). This period of joy and lifting of depression in company and in fun outings is only achievable with a certain level of financial comfort, which she is borrowing/temporarily enjoying at the Brettons' expense. Despite Père Silas' and M. Emanuel's faith in the power of good works, C.B. shows us that a person does need some society and positive experiences to lift oneself out of depression. Vocabulary note: when she says "hypochondria", it doesn't carry the modern meaning of someone who erroneously thinks they're ill. The older meaning of the word simply meant Depresssion.

message 11:

by

Lady Clementina, Moderator

(last edited May 01, 2022 05:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

LiLi wrote: "M. Paul Emanuel has very strict, Catholic views on propriety, which I believehe would apply to any demoiselle. He strikes me as misogynistic. (But maybe this is redundant.)

He doesn't seem to thin..."

I don't know that he necessarily seemed misogynistic--conservative, yes, controlling, also.

But what interested me was comparing Lucy's notions on propriety where she seems taken aback with what she sees as unethical, and now the same thing happening the other way. This then just makes it reflective of human nature--an us and them/right and wrong approach that all of us somewhere have, conscious or unconscious

He doesn't seem to thin..."

I don't know that he necessarily seemed misogynistic--conservative, yes, controlling, also.

But what interested me was comparing Lucy's notions on propriety where she seems taken aback with what she sees as unethical, and now the same thing happening the other way. This then just makes it reflective of human nature--an us and them/right and wrong approach that all of us somewhere have, conscious or unconscious

message 12:

by

Lady Clementina, Moderator

(last edited May 01, 2022 05:43AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

LiLi wrote: "Something that really stood out to me in these chapters is a theme also explored in _Shirley_: the power of money. Lucy is typically isolated because all she has is this job in a school, without re..."

Money is certainly a factor; that and the fact that Lucy is essentially friendless, even if she didn't have means, if she had somewhere to go to, like now she does the Brettons things would have been different, and she needn't have fallen into that depressive space; even if it didn't involve going out and enjoying society she'd have had company which was what she most needed.

Thanks for the note on hypochondria as well. I meant to look it up before posting but forgot all about it

Money is certainly a factor; that and the fact that Lucy is essentially friendless, even if she didn't have means, if she had somewhere to go to, like now she does the Brettons things would have been different, and she needn't have fallen into that depressive space; even if it didn't involve going out and enjoying society she'd have had company which was what she most needed.

Thanks for the note on hypochondria as well. I meant to look it up before posting but forgot all about it

LiLi wrote: "Historical note: the King would have been Leopold I, and his forlorn-looking son, Leopold II, a strange man now infamous for his brutal colonization of what is today the Democratic Republic of the ..."

Thanks Lili, Congo was sadly what also came to mind when I thought of them as being the Leopolds.

Thanks Lili, Congo was sadly what also came to mind when I thought of them as being the Leopolds.

LiLi wrote: "I admit I feel a bit cheated by this reveal. Lucy has chosen deliberately to conceal from us something she knew. I remember thinking when she met the stranger with long red hair who helped her loca..."

I'm sure we all do Lili; and that is part of Lucy's character; unlike say Jane Eyre, she isn't quite as straightforward with her thoughts and with things she knows; does that make her less likeable or us feel less sympathy for her is for us to see

I'm sure we all do Lili; and that is part of Lucy's character; unlike say Jane Eyre, she isn't quite as straightforward with her thoughts and with things she knows; does that make her less likeable or us feel less sympathy for her is for us to see

I wonder too if Lucy was a bit put out by Dr John not paying any real attention to her (hence her earlier bitter remark about him not considering her any more than the carpet), and so decided to wait for her moment.

I wonder too if Lucy was a bit put out by Dr John not paying any real attention to her (hence her earlier bitter remark about him not considering her any more than the carpet), and so decided to wait for her moment. A lot of coincidences too how Graham/Dr John keeps turning up in Lucy’s world. Is he the only Englishman in Villette?!

Right. As I noted in the previous section, I thought her having an epiphany while staring at Dr John was her realizing that he was Isidore. And then that reveal took five chapters instead of one (and I think she had to have it spelled out to her). Why Lucy didn't reveal Dr John's secret identity to us earlier is, I think, a cheap plot twist on C.B.'s part. As for her not telling Dr John, I think it is the reticence she has developed to match her reduced station in life. She doesn't think he'll care much if she tells him, and possibly doesn't want to advertise how low she's sunk since their younger years. After all, he's already treated her like a piece of furniture! Unfortunately we live in a classist society.

Right. As I noted in the previous section, I thought her having an epiphany while staring at Dr John was her realizing that he was Isidore. And then that reveal took five chapters instead of one (and I think she had to have it spelled out to her). Why Lucy didn't reveal Dr John's secret identity to us earlier is, I think, a cheap plot twist on C.B.'s part. As for her not telling Dr John, I think it is the reticence she has developed to match her reduced station in life. She doesn't think he'll care much if she tells him, and possibly doesn't want to advertise how low she's sunk since their younger years. After all, he's already treated her like a piece of furniture! Unfortunately we live in a classist society.I personally think her claim as the goddaughter of Mrs Bretton was probably enough to warrant her identifying herself and commanding some respect or consideration. But Lucy, as we've seen, is an extremely depressed person.

So about Lucy being essentially friendless: yes, the connections mean a lot. Money buys access. At the end of the day, we all buy friends. If you think about the ways you would generally go about trying to make friends in a new town, they all involve money. If you have to watch every penny, you won't have it. No joining a club or society, no taking a recreational/personal development course, no exchanges of dinner/tea at each other's houses or even a place to receive guests (in modern times this would also include meeting in a café), limited transportation options (which can be dangerous at night)...the absence of money significantly limits one's ability to make friends.

So about Lucy being essentially friendless: yes, the connections mean a lot. Money buys access. At the end of the day, we all buy friends. If you think about the ways you would generally go about trying to make friends in a new town, they all involve money. If you have to watch every penny, you won't have it. No joining a club or society, no taking a recreational/personal development course, no exchanges of dinner/tea at each other's houses or even a place to receive guests (in modern times this would also include meeting in a café), limited transportation options (which can be dangerous at night)...the absence of money significantly limits one's ability to make friends.

I have more to say about Lucy's relationship with the Brettons, but I will put it in the next section.

I have more to say about Lucy's relationship with the Brettons, but I will put it in the next section.

I'd probably see Lucy as more in the lines of an unreliable narrator like one sees more of in later fiction, keeping things back, telling them in a certain way etc. Part of her character perhaps than as the author trying to deceive us.

Re her reticence vis a vis Dr John, I wonder if it's just reduced circumstances since when you look at it, the Brettons are in exactly the same situation with the difference being that with Graham being a man, they have a chance at doing better which Lucy on her own doesn't. Perhaps we see this too as part of her generally secretive nature. A power she holds over dr john as she does over us

Re her reticence vis a vis Dr John, I wonder if it's just reduced circumstances since when you look at it, the Brettons are in exactly the same situation with the difference being that with Graham being a man, they have a chance at doing better which Lucy on her own doesn't. Perhaps we see this too as part of her generally secretive nature. A power she holds over dr john as she does over us

message 22:

by

Lady Clementina, Moderator

(last edited May 02, 2022 08:12AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Michaela wrote: "(I´m not that far, but obviously there´s a typo with the chapters: XVI not VI. :) )"

Yes, sorry, I only noticed later

Yes, sorry, I only noticed later

My favourite sections this week were Lucy’s Art Gallery encounter with M. Paul and her visit to the concert. Both revealed so much about her and the two men who are increasingly becoming a larger part of her life.

My favourite sections this week were Lucy’s Art Gallery encounter with M. Paul and her visit to the concert. Both revealed so much about her and the two men who are increasingly becoming a larger part of her life.The reveal was surprising. I enjoyed Lucy’s description of her waking up in a room from the past. For Dr. John not to have recognised her at the school shows just how much he wasn’t looking at her.

However, Dr. John’s kindness and skill as a doctor was exemplified in the way he treated Lucy once she was fit enough to leave her bed. His medicine consisted of improving her life experiences rather than pills or tonics. Leaving her at the art gallery was one dose of his medicine and the concert was another.

The art gallery (Interesting that the ‘Palace des Beaux-Arts now stands where Pensionnat used to be in Brussels) allowed Lucy to recharge her batteries and reaffirm her independence both of thought and spirit.

’ Dr. Bretton was a cicerone after my own heart; he would take me betimes, ere the galleries were filled, leave me there for two or three hours, and call for me when his own engagements were discharged. Meantime, I was happy; happy, not always in admiring, but in examining, questioning, and forming conclusions.’

I liked the way she decided to admire the pictures that she liked and not what was thought to be the best by the masses. Her confrontation with M. Paul was hilarious. Although he once more assumed that dominating, ‘I know best’ attitude, Lucy didn’t let him have it all his own way.

’ I assured him plainly I could not agree in this doctrine, and did not see the sense of it; whereupon, with his usual absolutism, he merely requested my silence, and also, in the same breath, denounced my mingled rashness and ignorance. A more despotic little man than M. Paul never filled a professor’s chair. I noticed, by the way, that he looked at the picture himself quite at his ease, and for a very long while: he did not, however, neglect to glance from time to time my way, in order, I suppose, to make sure that I was obeying orders, and not breaking bounds.

The irony of the argument about the Cleopatra painting was that she didn’t like it anyway, she was only on the seat in front of it having a rest. However she wasn’t going to make an excuse like that to M. Paul. Instead she took him on.

Lucy seems to both admire and denounce M. Paul, sometimes in the same sentence. She likes to rise to his challenges as if he is a spur to her mental lethargy.

The concert revealed to me that, whether she knows it herself or not, Lucy has fallen madly in love with Dr. John. This extract proves it.

‘ Through the whole performance—timid instrumental duets, conceited vocal solos, sonorous, brass-lunged choruses—my attention gave but one eye and one ear to the stage, the other being permanently retained in the service of Dr. Bretton: I could not forget him, nor cease to question how he was feeling, what he was thinking, whether he was amused or the contrary.’

Whether or not she is forcing herself to bury her feelings, knowing they will not be reciprocated is difficult to say. Could Dr. John have been partly the subject of her desperate confession in the church?

I liked the way Lucy described the difference between Dr. John and M. Paul.

‘ This way came Dr. John, in visage, in shape, in hue, as unlike the dark, acerb, and caustic little professor, as the fruit of the Hesperides might be unlike the sloe in the wild thicket; as the high-couraged but tractable Arabian is unlike the rude and stubborn “sheltie.”’

Trev wrote: "My favourite sections this week were Lucy’s Art Gallery encounter with M. Paul and her visit to the concert. Both revealed so much about her and the two men who are increasingly becoming a larger p..."

Dr John was probably too absorbed in Ginevra to be bothered by anyone else.

Re Lucy being in love with him, the reference to staring at his portrait back when she was 14 also showed that this had always been the case.

I liked her standing up to M Paul too; that was probably also why she I think was adamant in the matter of the costume, she had given into his whims for a bit but wanted to assert her independence and individuality as well

Dr John was probably too absorbed in Ginevra to be bothered by anyone else.

Re Lucy being in love with him, the reference to staring at his portrait back when she was 14 also showed that this had always been the case.

I liked her standing up to M Paul too; that was probably also why she I think was adamant in the matter of the costume, she had given into his whims for a bit but wanted to assert her independence and individuality as well

@Lady Clementina, the portrait was what finally convinced me what y'all had been saying all along about Lucy fancying Dr John.

@Lady Clementina, the portrait was what finally convinced me what y'all had been saying all along about Lucy fancying Dr John.

Ohhhhh. Yes, that is an interesting question. I'm still not accustomed to unreliable narrators, so mostly it's driving me batty. But indeed, it's another psychological layer, isn't it? I think C.B.'s best quality is her understanding of human nature and psychology. Hopefully by the end of the novel we'll get an answer to THE question! (and it had better not be 42)

Ohhhhh. Yes, that is an interesting question. I'm still not accustomed to unreliable narrators, so mostly it's driving me batty. But indeed, it's another psychological layer, isn't it? I think C.B.'s best quality is her understanding of human nature and psychology. Hopefully by the end of the novel we'll get an answer to THE question! (and it had better not be 42)

I think I was a bit confusing in my response as well. I meant to respond to Lili's observation re cheating the audience, since to my mind, as you also said Lucia, Lucy is rather an unreliable narrator in line with whose character it is to not say everything he or she knows, to hold back and perhaps even mislead. To me that's the element that also makes this a work that I was most in awe of amongst all of Charlotte Bronte's books (I haven't read The Prefessor though and none of her shorter, fantasy stuff) since Lucy is such a complex character and that comes across really well.

And if we think of her as secretive rather than deliberately misleading, it would also explain her holding back her own identity from Dr John as well

And if we think of her as secretive rather than deliberately misleading, it would also explain her holding back her own identity from Dr John as well

Lady Clementina wrote: "I think I was a bit confusing in my response as well. I meant to respond to Lili's observation re cheating the audience, since to my mind, as you also said Lucia, Lucy is rather an unreliable narra..."

Lady Clementina wrote: "I think I was a bit confusing in my response as well. I meant to respond to Lili's observation re cheating the audience, since to my mind, as you also said Lucia, Lucy is rather an unreliable narra..."The Anne Brontë blog reproduces an extract from a letter sent by Charlotte to her publishers before Villette was finally published.

’ In a letter to W. S. Williams in November 1852, she writes: ‘I fear they [readers] must be satisfied with what is offered: my palette affords no brighter tints – were I to attempt to deepen the reds or burnish the yellows I should but botch. Unless I am mistaken, the emotion of the book will be found to be kept throughout in tolerable subjection. As to the name of the heroine – I can hardly express what subtility of thought made me decide upon giving her a cold name; but, at first, I called her “Lucy Snowe” (spelt with an e) which “Snowe” I afterward changed to “Frost”. I rather regretted the change and wished it “Snowe” again: if not too late, I should like the alteration to be made now throughout the manuscript. A cold name she must have… for she has about her an external coldness.’

The external coldness that Charlotte describes could be interpreted in some instances as secretiveness. In the book so far I think we have mainly witnessed the external Lucy, with her inner most feelings only being reflected through metaphors about the weather and storms etc.

However, in the latest chapters, after her confession and then staying with the Brettons, she has described more of her inner feelings, thoughts and ideas. Could it be because of her greater freedom to be herself? She seems to be dreading going back to the school to be trapped in a dreary life once more.

Great comments. Re John Graham Bretton. His full name is given--actually emphasized-- in Ch. 1 and 2.

Great comments. Re John Graham Bretton. His full name is given--actually emphasized-- in Ch. 1 and 2.Ch. 1: "Mrs. Bretton and I sat alone in the drawing-room waiting her coming; John Graham Bretton being absent on a visit to one of his schoolfellows who lived in the country."

Ch. 2: “Miss Home,” pursued Graham, undeterred by his mother’s remonstrance, “might I have the honour to introduce myself, since no one else seems willing to render you and me that service? Your slave, John Graham Bretton.”

I wonder when we will connect with Miss Home again.

Just lately I came across a wonderful book, The Book of Qualities, in which qualities are personified. An example given on J. Ruth Gendler's webpage:

Just lately I came across a wonderful book, The Book of Qualities, in which qualities are personified. An example given on J. Ruth Gendler's webpage:

I am finding that Lucy frequently uses this technique, to very good effect. I wish I had been noting them down as I went along. One great example from ch. 20 is "hypochondria", which, as Lili has pointed out, meant depression.

Those eyes had looked on the visits of a certain ghost—had long waited the comings and goings of that strangest spectre, Hypochondria. Perhaps he saw her now on that stage, over against him, amidst all that brilliant throng. Hypochondria has that wont, to rise in the midst of thousands—dark as Doom, pale as Malady, and well-nigh strong as Death. Her comrade and victim thinks to be happy one moment—“Not so,” says she; “I come.” And she freezes the blood in his heart, and beclouds the light in his eye.Have you noticed any others?

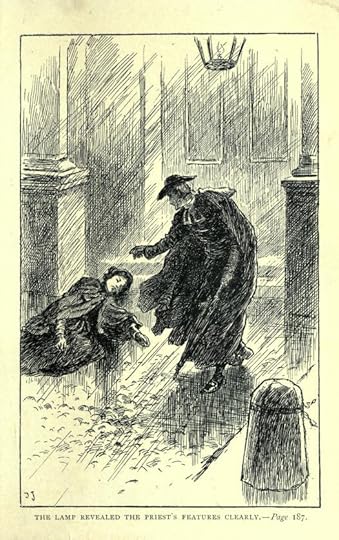

At the end of ch. 15, Lucy is lost in the dark. Her very life is at risk.

At the end of ch. 15, Lucy is lost in the dark. Her very life is at risk.

At the end of Ch. 20, she is lost in the dark again, but now she is with friends, especially Graham who takes charge and takes her to safety. (As in fact, he did the last time.) Lucy is able to enjoy the detour of one and a half hours.

It just struck me that Graham is her guardian angel. He has rescued her at least 3 times.

I have also noticed the personification, including some in the next section which I am halfway through. Good point Ginny about Graham always coming to Lucy’s rescue.

I have also noticed the personification, including some in the next section which I am halfway through. Good point Ginny about Graham always coming to Lucy’s rescue.If anyone is in the dark a little because of the longer passages of French included in the novel, this article (see link below) explains why Charlotte loved using French so much. I also found out from it that there are editions with translations of the French contained within. Does anyone have one of those?

http://www.annebronte.org/2021/10/24/...

Probably my favorite scene to date occurs in Chapter 18: Lucy angrily tells Dr. John that he is a slave to Ginevra, and storms out of the room. When she sees him that evening, his is anything but resentful, he is respectful and contrite.

Probably my favorite scene to date occurs in Chapter 18: Lucy angrily tells Dr. John that he is a slave to Ginevra, and storms out of the room. When she sees him that evening, his is anything but resentful, he is respectful and contrite.

Trev wrote: I also found out from it that there are editions with translations of the French contained within. Does anyone have one of those?..."

Trev wrote: I also found out from it that there are editions with translations of the French contained within. Does anyone have one of those?..."Mine has shorter bits right next to the text, and longer passages are translated in the notes at the back. Works pretty well. Thanks for the link.

LiLi wrote: "Which edition do you have? One of my friends wants to read this, but doesn't speak French."

LiLi wrote: "Which edition do you have? One of my friends wants to read this, but doesn't speak French."Arcturus Publishing, London. I think I picked it up in a used book store somewhere.

I think the Wordsworth eds would also probably have translations since they usually do carry a good set of endnotes.

LiLi wrote: "I admit I feel a bit cheated by this reveal. Lucy has chosen deliberately to conceal from us something she knew. I remember thinking when she met the stranger with long red hair who helped her loca..."

LiLi wrote: "I admit I feel a bit cheated by this reveal. Lucy has chosen deliberately to conceal from us something she knew. I remember thinking when she met the stranger with long red hair who helped her loca..."I realize Lucy is an unreliable narrator only when her ego is bruised. I feel that her disclosure of Dr. John's true identity has everything to do with him not recognizing her. Although she is quite independent, I feel that part of her wishes to have been recognized by him from their initial meeting at the school. She also likes to omit information when religion comes into play. Lucy may be a die-hard protestant when she is well, but when she loses control of her faculties, she reverts to Catholicism.

Lady Clementina wrote: "Trev wrote: "My favourite sections this week were Lucy’s Art Gallery encounter with M. Paul and her visit to the concert. Both revealed so much about her and the two men who are increasingly becomi..."

Lady Clementina wrote: "Trev wrote: "My favourite sections this week were Lucy’s Art Gallery encounter with M. Paul and her visit to the concert. Both revealed so much about her and the two men who are increasingly becomi..."Lucy standing up to M. Paul seems like payback for his treatment of her during the play. Although she gave into his demands, she needed something to relinquish her status as a pushover.

And what a contrast to last week’s closing developments, from a lonely, friendless existence at the Pensionnat which made Lucy despondent and quite ill, this week, she not only met old friends feeling wanted and perhaps ‘loved’ again, but in contrast to her existence so far in Villette both saw the town and partook of its social life. And we begin to see how Lucy doesn’t let readers on to all she knows quite as easily or instantly as we might think. While Dr John finally has a veil lifted off his eyes.

Summary

When we left Lucy last week, her deep desolation—from being all alone in the Pensionnat, with not a person to talk to—led to an illness and a confession to the priest. And on her way back, she fell faint. This week opens with Lucy somewhat delirious, not quite sure where she is, but seeing around her all manner of familiar things, things she remembers from 10 years ago, and her time at her godmother Mrs Bretton’s. She tries to convince herself that she’s imagining things but she isn’t and we soon find that not only is she under Mrs Bretton’s care but Graham Bretton is in fact, Dr John, something Lucy knew from the start, or at least the moment she stared at him. But unlike her, he failed to recognize her, knowing her only as the English teacher from the Pensionnat.

But Mrs Bretton is not as easily fooled and the first evening that Lucy comes down and sits with them, she is recognized. Now the care that she was under as a stranger, yet one whom Graham recognized becomes of a different degree with Mrs Bretton giving her all the attention she needs. While she mayn’t be overly effusive, Mrs Bretton does care for Lucy.

In Lucy and Graham’s relationship, we see a change, even compared to how things were 10 years ago. Lucy is open in her observations and tells him off over his blind devotion to Ginevra—it seems that he isn’t seeing even the obvious. But while this leads to a little quarrel, once Lucy offers an olive branch and they agree to disagree the two develop a friendship, closer most likely than when they were children for then there seemed no exchanges or conversations. Graham starts to show Lucy around town and she gets a chance to really see Villette, from its poorer quarters where Graham is well liked as a doctor, to its galleries and other places of interest.

The highlight of her visit is a concert which is presided over by M Josef Emmanuel, M Paul’s brother and for which Mrs Bretton buys her a pink dress, far removed from what she usually wears. The concert is attended by all the Labasscourian elite and the King and Queen with their court make an appearance. Ginevra and De Hamal are part of the entourage, and when Ginevra mocks Mrs Bretton to her companion, she goes one step too far, and Dr John finally sees her true nature, then also thinks back to other incidents (including her attitude to his presents) that reveal her for who she is. Now Lucy suddenly is in the opposite camp, defending Ginevra, while also being glad that Graham has finally seen sense.

Meanwhile at one visit to an art gallery, Lucy has an interesting encounter with Mr Paul, who disapproves not only of her being their alone, but of the somewhat ‘daring’ picture she is looking at, directing her to others where the subjects are more modestly dressed. Then again at the concert, where she avoids engaging in any conversation with him, he betrays anger, disapproval even. But is Lucy’s explanation the right one, or is there more to it than what she makes out (for we know that Lucy doesn’t quite let on all she knows).