Works of Thomas Hardy discussion

This topic is about

Tess of the D’Urbervilles

Tess of the d'Urbervilles

>

Tess of the D'Urbervilles - Phase the Fourth: Chapter 25 - 34

Here are LINKS TO EACH CHAPTER SUMMARY, for ease of location:

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

About the cover picture: the real "Tess"

As I said in the introductory comments Tess Durbeyfield was inspired by a real person, and this was Gertrude Bugler.

Gertrude Bugler was born in 1897 in Dorchester (Thomas Hardy's "Casterbridge") in Dorset. She was the daughter of Augusta, a local milkmaid who had attracted the attention of Thomas Hardy when he was 45. He saw her on his almost daily walks from his home Max Gate to the Kingston Maurward estate, where he was welcomed as a frequent visitor and found encouragement for his writing. But they never spoke, and Augusta married and had a family. Thomas Hardy did not see her again until he was 72, in 1913.

But that's another story ... which I'll continue at the beginning of Phase the Sixth :)

PLEASE NOTE

(This post has been edited, as it contained incorrect information in an article on Gertrude Bugler on wiki.)

As I said in the introductory comments Tess Durbeyfield was inspired by a real person, and this was Gertrude Bugler.

Gertrude Bugler was born in 1897 in Dorchester (Thomas Hardy's "Casterbridge") in Dorset. She was the daughter of Augusta, a local milkmaid who had attracted the attention of Thomas Hardy when he was 45. He saw her on his almost daily walks from his home Max Gate to the Kingston Maurward estate, where he was welcomed as a frequent visitor and found encouragement for his writing. But they never spoke, and Augusta married and had a family. Thomas Hardy did not see her again until he was 72, in 1913.

But that's another story ... which I'll continue at the beginning of Phase the Sixth :)

PLEASE NOTE

(This post has been edited, as it contained incorrect information in an article on Gertrude Bugler on wiki.)

Chapter 25: Summary

That evening Angel is still restless, so he goes outside. He is surprised by his own burst of passion, and wonders how they should act before others now. He had planned to come to Talbothays for a brief episode of education and observation, but now the outside world has become dull to him and the farm is transformed by Tess’s personality into a wonderful, abundant, homelike place.

Even apart from Tess the dairy has become important to Angel. He realises that his experiences here are as important as elsewhere, and that Tess is not a doll for his temporary pleasure but a human with her own “precious life”. This life is her only chance in this world, a chance given her by an “unsympathetic First Cause”, so Angel must be careful in his behaviour.

Angel realises he should probably avoid Tess for a while, but the thought is unwelcome to him. He decides to go home and ask his family and acquaintances if it doesn’t make sense for a farmer to choose a farm-woman for a wife.

At breakfast the four dairymaids who believe they are are in love with Angel Clare discover that he has gone home for a while, and they try to hide their despair. Dairyman Crick blithely discusses his eventual leaving, and guesses that Angel has about four months left at Talbothays.

At that time Angel is riding home to Emminster with some black pudding and mead; gifts for his family from Mrs. Crick. He watches the road and thinks about his potential future with Tess, and what his family and community would think if he married her.

Angel passes by his father’s church and sees some school-girls, and among them is their Sunday School teacher Mercy Chant, the pious woman his parents want him to marry. Angel thinks of the fertile valley and Tess, and tries to avoid Mercy.

Angel has come home on an impulse without warning his family, and he arrives at breakfast. Both his brothers, Felix and Cuthbert, are home from their respective positions. Their father, Reverend Clare, is an “honest, God-fearing man”. Thomas Hardy says he is one of a dying breed of low church clergymen, who is extreme and conservative in his views, but wins everyone’s admiration for his sincerity and fervency.

Angel imagines his father uncomprehending and condemning of the “aesthetic, sensuous, pagan pleasure in natural life and lush womanhood” that Angel has lately enjoyed. Rev. Clare cannot accept his son’s scepticism, but his heart is so kind that he feels and acts no differently towards Angel.

Angel sits down and again feels that he has changed while his family remains the same. His brothers notice that he behaves with the passionate freedom of a farmer, and has perhaps “lost culture”. Later Angel walks with them; they are both educated men who wear the glasses that are in fashion, read the poets in fashion, and believe the doctrines in fashion. Angel notices their recent “mental limitations” as they settle into their respective mindsets of the Church (Felix) and University (Cuthbert). Both are somewhat inferior in spirit to their father, and they have little curiosity for life or sense of the wider world beyond.

Felix comments on Angel’s farming future and advises him to not drop his morality and thought, as in his latest letters he seemed to be losing intelligence. Angel disparages Felix’s fixed ideas of dogma. They return home and Angel is particularly hungry after the huge breakfasts he is now used to, but neither parent returns until much later.

Angel looks around for his gifts from Mrs. Crick, but his mother has given the black puddings to the poor and put the mead in the medicine cabinet, as they never drink alcohol. Angel uses a rural expression and then feels embarrassed.

That evening Angel is still restless, so he goes outside. He is surprised by his own burst of passion, and wonders how they should act before others now. He had planned to come to Talbothays for a brief episode of education and observation, but now the outside world has become dull to him and the farm is transformed by Tess’s personality into a wonderful, abundant, homelike place.

Even apart from Tess the dairy has become important to Angel. He realises that his experiences here are as important as elsewhere, and that Tess is not a doll for his temporary pleasure but a human with her own “precious life”. This life is her only chance in this world, a chance given her by an “unsympathetic First Cause”, so Angel must be careful in his behaviour.

Angel realises he should probably avoid Tess for a while, but the thought is unwelcome to him. He decides to go home and ask his family and acquaintances if it doesn’t make sense for a farmer to choose a farm-woman for a wife.

At breakfast the four dairymaids who believe they are are in love with Angel Clare discover that he has gone home for a while, and they try to hide their despair. Dairyman Crick blithely discusses his eventual leaving, and guesses that Angel has about four months left at Talbothays.

At that time Angel is riding home to Emminster with some black pudding and mead; gifts for his family from Mrs. Crick. He watches the road and thinks about his potential future with Tess, and what his family and community would think if he married her.

Angel passes by his father’s church and sees some school-girls, and among them is their Sunday School teacher Mercy Chant, the pious woman his parents want him to marry. Angel thinks of the fertile valley and Tess, and tries to avoid Mercy.

Angel has come home on an impulse without warning his family, and he arrives at breakfast. Both his brothers, Felix and Cuthbert, are home from their respective positions. Their father, Reverend Clare, is an “honest, God-fearing man”. Thomas Hardy says he is one of a dying breed of low church clergymen, who is extreme and conservative in his views, but wins everyone’s admiration for his sincerity and fervency.

Angel imagines his father uncomprehending and condemning of the “aesthetic, sensuous, pagan pleasure in natural life and lush womanhood” that Angel has lately enjoyed. Rev. Clare cannot accept his son’s scepticism, but his heart is so kind that he feels and acts no differently towards Angel.

Angel sits down and again feels that he has changed while his family remains the same. His brothers notice that he behaves with the passionate freedom of a farmer, and has perhaps “lost culture”. Later Angel walks with them; they are both educated men who wear the glasses that are in fashion, read the poets in fashion, and believe the doctrines in fashion. Angel notices their recent “mental limitations” as they settle into their respective mindsets of the Church (Felix) and University (Cuthbert). Both are somewhat inferior in spirit to their father, and they have little curiosity for life or sense of the wider world beyond.

Felix comments on Angel’s farming future and advises him to not drop his morality and thought, as in his latest letters he seemed to be losing intelligence. Angel disparages Felix’s fixed ideas of dogma. They return home and Angel is particularly hungry after the huge breakfasts he is now used to, but neither parent returns until much later.

Angel looks around for his gifts from Mrs. Crick, but his mother has given the black puddings to the poor and put the mead in the medicine cabinet, as they never drink alcohol. Angel uses a rural expression and then feels embarrassed.

Real Life Locations:

Thomas Hardy's “Emminster”, where Parson Clare and his family live is in real life Beaminster, a town about 15 miles NW of Dorchester. (It’s a lovely old-fashioned little town with a great market!) Beaminster dates back to the Anglo-Saxon age, around the 7th century, when it was known as “Bebingmynster”, meaning the church of Bebbe. It has been a centre of manufacture of linen and woollens, the raw materials for which were produced in the surrounding countryside:

Beaminster town centre

The church Angel passes by is the parish church, St. Mary’s. Beaminster parish church is notable for its architecture. Dating from the 13th and 15th centuries, its best feature is its magnificent early 16th century west tower. The tower served a grim purpose after the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685, when the butchered quarters of those executed were hung like carrion from its lofty heights.

St. Mary's Parish Church - Beaminster

Thomas Hardy's “Emminster”, where Parson Clare and his family live is in real life Beaminster, a town about 15 miles NW of Dorchester. (It’s a lovely old-fashioned little town with a great market!) Beaminster dates back to the Anglo-Saxon age, around the 7th century, when it was known as “Bebingmynster”, meaning the church of Bebbe. It has been a centre of manufacture of linen and woollens, the raw materials for which were produced in the surrounding countryside:

Beaminster town centre

The church Angel passes by is the parish church, St. Mary’s. Beaminster parish church is notable for its architecture. Dating from the 13th and 15th centuries, its best feature is its magnificent early 16th century west tower. The tower served a grim purpose after the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685, when the butchered quarters of those executed were hung like carrion from its lofty heights.

St. Mary's Parish Church - Beaminster

Religion:

This was quite a dense chapter, although the action was not moved forward very much. I got the impression that here Thomas Hardy was sharing his own thoughts and depth of reading about various doctrinal issues in Protestantism. If we have any experts in this field of Theology, please do share what you know about the details! Despite my English low church (Baptist) upbringing I was resorting to google quite a lot, about the doctrinal issues.

Angel Clare is like a fish out of water here, amidst his Christian family. We were told that even his older sister had married a Christian missionary, and has gone overseas.

It is noticeable that Reverend Clare gets the most respect among the group of Christians Thomas Hardy portrays, but it is the man himself: his sincerity and passion, that are portrayed positively, more than the specifics of his religious beliefs. This parson is constant: his whole nature leans one way, and unlike his sons, he remains true to it despite the fashions of the church and society. Angel sees the pagan nature of his current rural life, and contrasts it with his father’s austerity. The Reverend’s kindness makes his extreme and harsh religious beliefs feel more human.

The religious section reaches a head when Thomas Hardy disparages the older brothers for their unoriginality and lack of conviction. The author's social and religious critique is at its sharpest here. Felix and Cuthbert Clare are perfectly conventional, and seem like lifeless cutouts of what their society wants them to be. They are more socially proper than Angel, Tess, or Reverend Clare, but they are rigid, have lost their sense of wonder in the world and can no longer empathise with other points of view.

This was quite a dense chapter, although the action was not moved forward very much. I got the impression that here Thomas Hardy was sharing his own thoughts and depth of reading about various doctrinal issues in Protestantism. If we have any experts in this field of Theology, please do share what you know about the details! Despite my English low church (Baptist) upbringing I was resorting to google quite a lot, about the doctrinal issues.

Angel Clare is like a fish out of water here, amidst his Christian family. We were told that even his older sister had married a Christian missionary, and has gone overseas.

It is noticeable that Reverend Clare gets the most respect among the group of Christians Thomas Hardy portrays, but it is the man himself: his sincerity and passion, that are portrayed positively, more than the specifics of his religious beliefs. This parson is constant: his whole nature leans one way, and unlike his sons, he remains true to it despite the fashions of the church and society. Angel sees the pagan nature of his current rural life, and contrasts it with his father’s austerity. The Reverend’s kindness makes his extreme and harsh religious beliefs feel more human.

The religious section reaches a head when Thomas Hardy disparages the older brothers for their unoriginality and lack of conviction. The author's social and religious critique is at its sharpest here. Felix and Cuthbert Clare are perfectly conventional, and seem like lifeless cutouts of what their society wants them to be. They are more socially proper than Angel, Tess, or Reverend Clare, but they are rigid, have lost their sense of wonder in the world and can no longer empathise with other points of view.

What of Mercy Chant? Her name must surely be an aptronym, describing an upright churchwoman.

It is the first time we have had a glimpse of Angel’s intended wife. Angel himself tries to avoid her; she is so different from Tess. As well as being scholarly, she represents the conventional properness and repression of her class and background, and contrasts with wild, natural Tess. I found myself wondering whether Mercy will have her own story, because after all Mercy is herself a unique woman, but the story is Tess’s, so perhaps not.

It is the first time we have had a glimpse of Angel’s intended wife. Angel himself tries to avoid her; she is so different from Tess. As well as being scholarly, she represents the conventional properness and repression of her class and background, and contrasts with wild, natural Tess. I found myself wondering whether Mercy will have her own story, because after all Mercy is herself a unique woman, but the story is Tess’s, so perhaps not.

Even within this contemplative tussle, we do have humour.

Angel is used to the hearty meals of a farmer, and finds his family’s austerity stifling. The contrast between meals at Talbothays and in the Clare household is emphasised. The farmers embrace their appetites and pleasures, but at the end of the chapter is is clear how much the Clares deny themselves.

The date is set for Angel’s departure from Talbothays, when everything will be bound to change again. The dairymaids still have something to hold on to: they both hope and despair. We do have humour here too, in the dairyman Mr. Crick’s blindness to his workers’ passions.

Angel is used to the hearty meals of a farmer, and finds his family’s austerity stifling. The contrast between meals at Talbothays and in the Clare household is emphasised. The farmers embrace their appetites and pleasures, but at the end of the chapter is is clear how much the Clares deny themselves.

The date is set for Angel’s departure from Talbothays, when everything will be bound to change again. The dairymaids still have something to hold on to: they both hope and despair. We do have humour here too, in the dairyman Mr. Crick’s blindness to his workers’ passions.

I particularly like the whimsical association of Tess with the very fabric of the farm buildings and surroundings here:

“The aged and lichened brick gables breathed forth “Stay!” The windows smiled, the door coaxed and beckoned, the creeper blushed confederacy. A personality within it was so far-reaching in her influence as to spread into and make the bricks, mortar, and whole overhanging sky throb with a burning sensibility. Whose was this mighty personality? A milkmaid’s.”

Tess brings out Angel’s more liberated inner nature, but his repressed conventionality quickly returns. Tess has the power to affect Angel’s mindset and seemingly the entire environment, although it may be that she is just perfectly aligned with Nature.

“The aged and lichened brick gables breathed forth “Stay!” The windows smiled, the door coaxed and beckoned, the creeper blushed confederacy. A personality within it was so far-reaching in her influence as to spread into and make the bricks, mortar, and whole overhanging sky throb with a burning sensibility. Whose was this mighty personality? A milkmaid’s.”

Tess brings out Angel’s more liberated inner nature, but his repressed conventionality quickly returns. Tess has the power to affect Angel’s mindset and seemingly the entire environment, although it may be that she is just perfectly aligned with Nature.

Now we know the passion Thomas Hardy himself felt for the daughter of a milkmaid (Gertrude Bugler: see the introductory post), this makes me wonder how much of himself he had put into the character of Angel Clare:

“Despite his heterodoxy, faults, and weaknesses, Clare was a man with a conscience.”

Doesn’t this sum up Thomas Hardy too?

Angel Clare makes many wise and admirable observations which contrast with Alec’s carelessness. It seems that he shares Thomas Hardy’s idea of a compassionless God or predestined fate. Did you notice the words “an unsympathetic First Cause” - as if God is toying with Tess.

Angel is constantly trying to reign in his emotions, and his return home symbolises the importance he places on the opinions of others, despite what his inner nature feels. Angel tries to reconcile his innate, natural love for Tess with the opinions of society and his family. In his passion, he believes that such reconciliation is possible. Perhaps it is … what do you think?

“Despite his heterodoxy, faults, and weaknesses, Clare was a man with a conscience.”

Doesn’t this sum up Thomas Hardy too?

Angel Clare makes many wise and admirable observations which contrast with Alec’s carelessness. It seems that he shares Thomas Hardy’s idea of a compassionless God or predestined fate. Did you notice the words “an unsympathetic First Cause” - as if God is toying with Tess.

Angel is constantly trying to reign in his emotions, and his return home symbolises the importance he places on the opinions of others, despite what his inner nature feels. Angel tries to reconcile his innate, natural love for Tess with the opinions of society and his family. In his passion, he believes that such reconciliation is possible. Perhaps it is … what do you think?

One of the questions I have about Hardy is highlighted in this chapter. Throughout the novel, Hardy has liberally introduced references to mythology, the Bible, philosophy, and history. I have wondered exactly who Hardy’s intended audience would be. Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference.

One of the questions I have about Hardy is highlighted in this chapter. Throughout the novel, Hardy has liberally introduced references to mythology, the Bible, philosophy, and history. I have wondered exactly who Hardy’s intended audience would be. Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference.One does not need identify and understand all of an author’s references to appreciate the novel. Still, can anyone help me understand who Hardy’s intended audience would have been?

Peter wrote: "Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference ..."

Funnily enough, reading Tess of the D'Urbervilles at age 17 was the first time I'd ever heard of Walt Whitman! I'm not sure in general his English readers of the time would have fared much better. At odd times, I've tried to get to grips with Walt Whitman's poetry but never really managed it, so was hoping someone might pick up the reference.

As for Thomas Hardy's audience, well that's a lot more straightforward (unless I'm misunderstanding you). It was the general public and church leaders of the time, whom he saw as over-censorious.

Note the subtitle A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented. This was the cause of great concern. It challenged the sexual morals of late Victorian England, and fell foul of the current censorship issues. Thomas Hardy refused to back down and gave the novel the subtitle “A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented” so that no one could ever doubt his intent and his feelings.

Tess of the D'Urbervilles was Thomas Hardy’s second to last novel, but he had a difficult time having it published because of this aspect. It had mixed reviews from the critics, but the public loved it. As I mentioned in the introductory comments, it first appeared in a censored version as a newspaper serial, in 1891, then in book form in three volumes in 1891, and as a single volume in 1892. Now though, it is considered to be a masterpiece.

The back story continues to be sad. When Thomas Hardy's next novel Jude the Obscure was published, it was immediately branded as immoral. It was even publicly burned by the Bishop of Salisbury, who considered it indecent: “probably in his despair”, wrote Thomas Hardy later, “at not being able to burn me”.

Brokenhearted, Thomas Hardy was never to write another novel again. He concentrated on his poetry, which had always been his first love. Now, we see the aspects which so shocked the church as largely tragic.

But he retained a great affection for Tess.

Is this what you were getting at, Peter?

Funnily enough, reading Tess of the D'Urbervilles at age 17 was the first time I'd ever heard of Walt Whitman! I'm not sure in general his English readers of the time would have fared much better. At odd times, I've tried to get to grips with Walt Whitman's poetry but never really managed it, so was hoping someone might pick up the reference.

As for Thomas Hardy's audience, well that's a lot more straightforward (unless I'm misunderstanding you). It was the general public and church leaders of the time, whom he saw as over-censorious.

Note the subtitle A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented. This was the cause of great concern. It challenged the sexual morals of late Victorian England, and fell foul of the current censorship issues. Thomas Hardy refused to back down and gave the novel the subtitle “A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented” so that no one could ever doubt his intent and his feelings.

Tess of the D'Urbervilles was Thomas Hardy’s second to last novel, but he had a difficult time having it published because of this aspect. It had mixed reviews from the critics, but the public loved it. As I mentioned in the introductory comments, it first appeared in a censored version as a newspaper serial, in 1891, then in book form in three volumes in 1891, and as a single volume in 1892. Now though, it is considered to be a masterpiece.

The back story continues to be sad. When Thomas Hardy's next novel Jude the Obscure was published, it was immediately branded as immoral. It was even publicly burned by the Bishop of Salisbury, who considered it indecent: “probably in his despair”, wrote Thomas Hardy later, “at not being able to burn me”.

Brokenhearted, Thomas Hardy was never to write another novel again. He concentrated on his poetry, which had always been his first love. Now, we see the aspects which so shocked the church as largely tragic.

But he retained a great affection for Tess.

Is this what you were getting at, Peter?

Bionic Jean wrote: "Peter wrote: "Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Peter wrote: "Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference ..."Funn..."

Yes Jean. Thanks. Each writer wishes to have their words, ideas and stories embraced by the - or should I say - a reading public. It would be wonderful if an author would appeal to every reader, but I doubt that happens very much. An example would be James Joyce. With the exception of ‘The Dubliners’ I have never been able to finish any of his novels. I have valiantly tried ‘Ulysses’ many times, and every time stumbled, fumbled, and given up.

And now I will mention Dickens. :-) I believe the majority of his reading public, in general, would stumble when appreciating Hardy. Joyce, Dickens, and Hardy are all grand writers in their own way. I just wonder to what degree the general audience for such writers would overlap.

Peter wrote: "I just wonder to what degree the general audience for such writers would overlap ..."

That's a fascinating question! I'm adding that to our post-read topics. I like that both Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy (later) had an adoring public though :)

That's a fascinating question! I'm adding that to our post-read topics. I like that both Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy (later) had an adoring public though :)

Peter wrote: "Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference..."

I discovered Walt Whitman in college, which like Jean was after my first reading of Tess, so the first time I read this chapter the reference to Whitman went right over my head. But in 1891, even people who had not read Whitman would have probably recognized him as a scandalous poet. He wrote about the body, and the material world in vivid lines, like this one from Song of Myself (which is in the same book of poetry as the lines Hardy quotes in this chapter):

I believe in the flesh and the appetites,

Seeing, hearing, feeling, are miracles, and each part and tag of me is a miracle.

Divine am I inside and out, and I make holy whatever I touch or am touch’d from,

The scent of these arm-pits aroma finer than prayer,

This head more than churches, bibles, and all the creeds.

I'm sorry for such a long quote, but I think it exemplifies how Whitman contrasts with Angel's father's heroes: Luther, Calvin, Schopnehauer, and maybe that's Hardy's purpose for quoting Walt Whitman. It emphasizes Angel's heterodoxy with his father's religion.

I discovered Walt Whitman in college, which like Jean was after my first reading of Tess, so the first time I read this chapter the reference to Whitman went right over my head. But in 1891, even people who had not read Whitman would have probably recognized him as a scandalous poet. He wrote about the body, and the material world in vivid lines, like this one from Song of Myself (which is in the same book of poetry as the lines Hardy quotes in this chapter):

I believe in the flesh and the appetites,

Seeing, hearing, feeling, are miracles, and each part and tag of me is a miracle.

Divine am I inside and out, and I make holy whatever I touch or am touch’d from,

The scent of these arm-pits aroma finer than prayer,

This head more than churches, bibles, and all the creeds.

I'm sorry for such a long quote, but I think it exemplifies how Whitman contrasts with Angel's father's heroes: Luther, Calvin, Schopnehauer, and maybe that's Hardy's purpose for quoting Walt Whitman. It emphasizes Angel's heterodoxy with his father's religion.

Thank you Bridget! I did not know Walt Whitman was considered a scandalous poet! So that now makes perfect sense, and clarifies it for me :)

Bridget wrote: "Peter wrote: "Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference..."

Bridget wrote: "Peter wrote: "Now, in this chapter, Hardy makes reference to Walt Whitman. How many readers of Hardy would be well acquainted with Whitman and thus his reason for including the reference..."I dis..."

Hi Bridget

Thank you for the insights and comments. I too first experienced Whitman in university. It was a revelation to me. The quotation you provided fits perfectly into the scope of what is occurring in ‘Tess.’

More and more I am in awe of the breadth and depth of Hardy’s knowledge.

Hardy also quotes from Algernon Swinburne when he describes how Retty and the other unfavored milkmaids look forward to Angel's last four months at Talbothays as "pleasure girdled about with pain." I'm not familiar with Swinburne's poetry, but I read that he was considered scandalous and decadent. He was a masochist and a dominant theme in his poetry is the relationship between pleasure and pain.

Hardy also quotes from Algernon Swinburne when he describes how Retty and the other unfavored milkmaids look forward to Angel's last four months at Talbothays as "pleasure girdled about with pain." I'm not familiar with Swinburne's poetry, but I read that he was considered scandalous and decadent. He was a masochist and a dominant theme in his poetry is the relationship between pleasure and pain.

Clare thinks of the maids back at Talbothays as "the impassioned, sun-flushed, summer-saturated heathens." It reminds me of Byron: "What men call gallantry, and gods adultery, Is much more common where the climate's sultry."

Clare thinks of the maids back at Talbothays as "the impassioned, sun-flushed, summer-saturated heathens." It reminds me of Byron: "What men call gallantry, and gods adultery, Is much more common where the climate's sultry."

Peter - “More and more I am in awe of the breadth and depth of Hardy’s knowledge.”

Me too! I find it amazing that two of my absolute favourite authors: Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens, did not go to university. They are so erudite and well-read.

And I am so grateful when others such as Bridget and now Erich bring up references that I had not noticed.

Me too! I find it amazing that two of my absolute favourite authors: Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens, did not go to university. They are so erudite and well-read.

And I am so grateful when others such as Bridget and now Erich bring up references that I had not noticed.

Erich - Thank you so much for the references to Algernon Charles Swinburne, and your subsequent associations of thought with Lord Byron, and for the explanation of why they are so apt! The more I learn about Chapter 25, the deeper I realise how powerful and significant the writing here is. This weekend there is a conference about Thomas Hardy and Religion in Salisbury. How I wish I could be there! Anyway, moving on …

Chapter 26: Summary

That night after family prayers, Angel finally summons the courage to discuss his situation with his father. He talks of his plan to set up a farm in either England or the Colonies, and Reverend Clare reveals that he has been saving up money for Angel’s future land expenses. Angel is touched, and so he brings up the subject of marriage. Mr. Clare insists his wife be at least a good Christian woman, and mentions Mercy Chant.

Angel argues that he ought to marry someone who could help him with farming, but Mr. Clare is still caught up on the details of Mercy’s beliefs. Angel says that Providence has given him a woman just as pure and faithful as Mercy, but with skills in agriculture instead of religion.

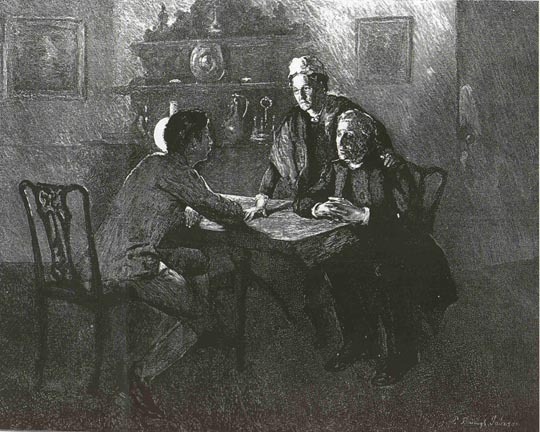

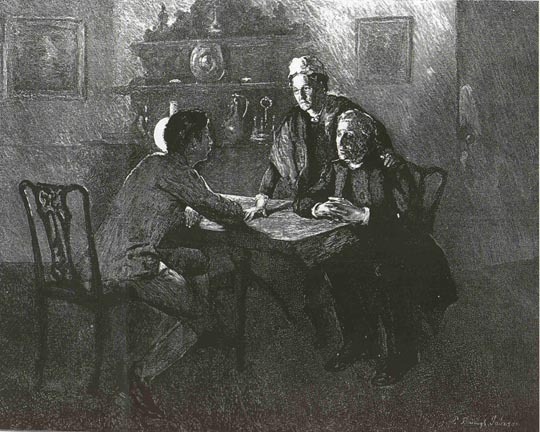

"'Is she of a family such as you would care to marry into -- a lady, in short?' asked his startled mother [Angel and his mother]" - E. Borough Johnson - "The Graphic"

Mrs. Clare interrupts to ask about Tess’s family. Angel admits that she is not a “lady”, but downplays the importance of ancestry when one is working the land. He compliments Tess for living what poets can only write about, and highlights her Christian faith, although as Thomas Hardy points out, earlier he had scorned this as a façade for the milkmaids’ more pagan, naturalistic lifestyle.

Considering his other rebellions, the Clares are pleased that Angel has at least chosen a Christian girl, and they offer to meet her. Angel doesn’t give many details, in case their middle-class prejudices might make his parents biased against Tess as she is. In discussing her, Angel realises that what he loves about Tess is not her skill or intelligence but her inherent vitality, and he sees that there can be more difference in spirits and attitude within one class, than in women across different social classes.

Angel departs in the morning, avoiding travelling with his brothers and eager to return to Tess. His father rides with him for a while, discussing problems of the parish. Reverend Clare mentions a particular young sinner named d’Urberville. Angel knows about the old family, but Mr. Clare says this young man is no relation. He had sought out the young d’Urberville, who had a reputation for sins of passion, and preached to him. The young man had responded with angry and insulting remarks to the Reverend.

Angel is sad that his father subjects himself to such attacks, but Mr. Clare brushes it off. He says he has been struck by sinners before, but if he was able to save them then it was worth it. Angel does not agree with his father’s views but respects his conviction, and admires that the Reverend never asked about Tess’s wealth. Angel feels closer to his father than his brothers are.

That night after family prayers, Angel finally summons the courage to discuss his situation with his father. He talks of his plan to set up a farm in either England or the Colonies, and Reverend Clare reveals that he has been saving up money for Angel’s future land expenses. Angel is touched, and so he brings up the subject of marriage. Mr. Clare insists his wife be at least a good Christian woman, and mentions Mercy Chant.

Angel argues that he ought to marry someone who could help him with farming, but Mr. Clare is still caught up on the details of Mercy’s beliefs. Angel says that Providence has given him a woman just as pure and faithful as Mercy, but with skills in agriculture instead of religion.

"'Is she of a family such as you would care to marry into -- a lady, in short?' asked his startled mother [Angel and his mother]" - E. Borough Johnson - "The Graphic"

Mrs. Clare interrupts to ask about Tess’s family. Angel admits that she is not a “lady”, but downplays the importance of ancestry when one is working the land. He compliments Tess for living what poets can only write about, and highlights her Christian faith, although as Thomas Hardy points out, earlier he had scorned this as a façade for the milkmaids’ more pagan, naturalistic lifestyle.

Considering his other rebellions, the Clares are pleased that Angel has at least chosen a Christian girl, and they offer to meet her. Angel doesn’t give many details, in case their middle-class prejudices might make his parents biased against Tess as she is. In discussing her, Angel realises that what he loves about Tess is not her skill or intelligence but her inherent vitality, and he sees that there can be more difference in spirits and attitude within one class, than in women across different social classes.

Angel departs in the morning, avoiding travelling with his brothers and eager to return to Tess. His father rides with him for a while, discussing problems of the parish. Reverend Clare mentions a particular young sinner named d’Urberville. Angel knows about the old family, but Mr. Clare says this young man is no relation. He had sought out the young d’Urberville, who had a reputation for sins of passion, and preached to him. The young man had responded with angry and insulting remarks to the Reverend.

Angel is sad that his father subjects himself to such attacks, but Mr. Clare brushes it off. He says he has been struck by sinners before, but if he was able to save them then it was worth it. Angel does not agree with his father’s views but respects his conviction, and admires that the Reverend never asked about Tess’s wealth. Angel feels closer to his father than his brothers are.

Religion: the Legal Position

There was a great deal of controversy about the various Christian religious denominations during the 19th century, and this often comes through in the novels from that time. For instance North and South (1855) by Elizabeth Gaskell begins with the Reverend Hale (Margaret’s father) moving his whole family away from the prosperous South, as he felt preaching in the church there was a sham, and did not accord with his increasingly non-conformist beliefs. He was a dissenter from the Anglican faith.

Tess of the D’Urbervilles was published in 1891, but we can tell from what Reverend Clare says that feelings still ran high. There had been various Acts of Parliament which relate to this. The Reform Act (1832) ensured that the Church of England remained the State religion. It made a large rift between the State and the Church in order to ensure that the Church of England was the major Church. It seems to have been designed to limit the power of Catholics and other denominations in parish matters, except within their own churches.

Then there was the Ecclesiastical Titles Act (1851) which made it a criminal offence for anyone outside the established Anglican Church to use any episcopal title “of any city, town or place … in the United Kingdom”. So the clergy of other denominations had to be very careful what title they gave themselves.

This is a very complicated area, but I can see that it would be easy at this time for the clergy of other denominations to feel persecuted and on the defensive.

There was a great deal of controversy about the various Christian religious denominations during the 19th century, and this often comes through in the novels from that time. For instance North and South (1855) by Elizabeth Gaskell begins with the Reverend Hale (Margaret’s father) moving his whole family away from the prosperous South, as he felt preaching in the church there was a sham, and did not accord with his increasingly non-conformist beliefs. He was a dissenter from the Anglican faith.

Tess of the D’Urbervilles was published in 1891, but we can tell from what Reverend Clare says that feelings still ran high. There had been various Acts of Parliament which relate to this. The Reform Act (1832) ensured that the Church of England remained the State religion. It made a large rift between the State and the Church in order to ensure that the Church of England was the major Church. It seems to have been designed to limit the power of Catholics and other denominations in parish matters, except within their own churches.

Then there was the Ecclesiastical Titles Act (1851) which made it a criminal offence for anyone outside the established Anglican Church to use any episcopal title “of any city, town or place … in the United Kingdom”. So the clergy of other denominations had to be very careful what title they gave themselves.

This is a very complicated area, but I can see that it would be easy at this time for the clergy of other denominations to feel persecuted and on the defensive.

I’m still trying to nail the exact religion Reverend Clare is. We were told that Mercy Chant is an expert in antinomianism, which means she follows the doctrine which states that Christians are freed by grace from the necessity of obeying the Mosaic Law. (i.e. the Ten Commandments received from God by Moses). The antinomians rejected the very notion of obedience as being legalistic; to them the good life flowed from the inner working of the Holy Spirit.

Towards the end of today’s chapter, when his father is confiding in him, Reverend Clare says to Angel that his “brother clergymen whom he loved” were cold to him, “because of his strict interpretations of the New Testament by the light of what they deemed a pernicious Calvinistic doctrine.”

This reminds me a little of how the Church of England - and to some extent nonconformists too - view the Plymouth Brethren. The way the Reverend Clare actively seeks out “delinquents” to show them the grace of God, saying with a shining face, “I have borne blows from men in a mad state of intoxication”, reminds me of the Salvation Army and Baptists, but I can’t get much further.

As I mentioned yesterday, please speak up if you know more about this! Certainly we see that Reverend Clare’s religion is an austere and self-denying one. Yesterday both Clare parents denied themselves food at the proper time, so that they could give it to the poor. The Plymouth Brethren also deny themselves entertainment; today not using machines (such TVs and computers).

Towards the end of today’s chapter, when his father is confiding in him, Reverend Clare says to Angel that his “brother clergymen whom he loved” were cold to him, “because of his strict interpretations of the New Testament by the light of what they deemed a pernicious Calvinistic doctrine.”

This reminds me a little of how the Church of England - and to some extent nonconformists too - view the Plymouth Brethren. The way the Reverend Clare actively seeks out “delinquents” to show them the grace of God, saying with a shining face, “I have borne blows from men in a mad state of intoxication”, reminds me of the Salvation Army and Baptists, but I can’t get much further.

As I mentioned yesterday, please speak up if you know more about this! Certainly we see that Reverend Clare’s religion is an austere and self-denying one. Yesterday both Clare parents denied themselves food at the proper time, so that they could give it to the poor. The Plymouth Brethren also deny themselves entertainment; today not using machines (such TVs and computers).

Mr. Clare is completely sincere in his beliefs, and in this he seems to be more similar to Angel than he is to his other two sons. Angel realises that his father is so immersed in his beliefs that he does not care about Tess’s worldly situation, but only if her faith is pure. Angel believes that even though they are different, this is better than his brothers, who are little more than servants to society’s whims.

Thomas Hardy stresses Reverend Clare’s kindness, over the harshness of his beliefs. He too though, like Angel, is lost in his own world, and sees true Christian doctrine as the most important part of marriage. He remains adamant about this. Angel has to “translate” his life into his father’s religious language, but for now Angel seems to be good at existing in two worlds at once! He even frames his meeting with Tess as the work of God, and he tries to emphasise her Christianity, even though before he viewed the church-going of the dairy workers as mere bowing to convention.

This makes me suspect that Angel might be dissembling a little here. Is it manipulative of him to represent Tess thus? Or do you consider this is fair, and just him trying to give her the best chance with his parents, and their devout beliefs? Angel has to downplay the part of Tess that he loves the most, which is her ancient pagan spirit and natural purity.

Mrs. Clare seems more worldly than her husband, and raises the question of their social class. Angel understands the deep divide between his family’s world and Tess’s, and knows that they might disapprove of her because of external circumstances alone. For now he is blinded by love and so can look beyond the strict roles of convention, but he is still wise to prepare his austere family for the Nature-child Tess.

Thomas Hardy stresses Reverend Clare’s kindness, over the harshness of his beliefs. He too though, like Angel, is lost in his own world, and sees true Christian doctrine as the most important part of marriage. He remains adamant about this. Angel has to “translate” his life into his father’s religious language, but for now Angel seems to be good at existing in two worlds at once! He even frames his meeting with Tess as the work of God, and he tries to emphasise her Christianity, even though before he viewed the church-going of the dairy workers as mere bowing to convention.

This makes me suspect that Angel might be dissembling a little here. Is it manipulative of him to represent Tess thus? Or do you consider this is fair, and just him trying to give her the best chance with his parents, and their devout beliefs? Angel has to downplay the part of Tess that he loves the most, which is her ancient pagan spirit and natural purity.

Mrs. Clare seems more worldly than her husband, and raises the question of their social class. Angel understands the deep divide between his family’s world and Tess’s, and knows that they might disapprove of her because of external circumstances alone. For now he is blinded by love and so can look beyond the strict roles of convention, but he is still wise to prepare his austere family for the Nature-child Tess.

What do we think to the mention of the young "upstart squire named d’Urberville", with a blind mother? We know who this must be! It did serve to clarify Angel’s beliefs about old families to us. His father thought he hated the very idea of them, but Angel said he has a “fondness” for the idea in art and history. Perhaps there is a chance for Tess, after all?

However, I’m not sure with this hint about Alec. It brings up the dark past, and shows that Tess’s happiness might be fragile. Perhaps she can never really be free; her past could always rise up and work against her.

Another thought is that we have two contrasting atttidudes apart from Angel’s. The Reverend Clare is contrasted with Alec not only in his beliefs, but in the endurance of his convictions.

However, I’m not sure with this hint about Alec. It brings up the dark past, and shows that Tess’s happiness might be fragile. Perhaps she can never really be free; her past could always rise up and work against her.

Another thought is that we have two contrasting atttidudes apart from Angel’s. The Reverend Clare is contrasted with Alec not only in his beliefs, but in the endurance of his convictions.

This Phase is titled “The Consequence”, and so far all we have seen is Angel’s wrestling with his conscience, and trying to persuade his family and himself that he could marry Tess. Where could we go from here?

I feel a sense of foreboding … but we have not heard about Tess.

I feel a sense of foreboding … but we have not heard about Tess.

I don’t think it’s been mentioned yet, but Christopher Nicholson’s ‘Winter’ (Fourth Estate, 2014) imagines the effect that Gertrude Bugler’s arrival at Max Gate had on the Hardys’ lives when she is cast as Tess in its initial production. I’m not sure that the author has the timeline correct (it’s likely that he has, and my own memory is cloudy) but it was entertaining and insightful when I read it.

I don’t think it’s been mentioned yet, but Christopher Nicholson’s ‘Winter’ (Fourth Estate, 2014) imagines the effect that Gertrude Bugler’s arrival at Max Gate had on the Hardys’ lives when she is cast as Tess in its initial production. I’m not sure that the author has the timeline correct (it’s likely that he has, and my own memory is cloudy) but it was entertaining and insightful when I read it. The blurb says, “In this delicately-wrought novel set in the 1920s, inspired by the first production of Tess, Christopher Nicholson presents three impassioned characters at a critical moment in their lives. A subtle psychological portrait of a great writer in the depths of old age, Winter is also a profound examination of love and desire, and their attendant hopes and disappointments.”

I can’t remember if there are spoilers in its content, but to be on the safe side, I’d recommend leaving off reading until our current quest is completed.

Wow, thanks David! Here it is:

Winter by Christopher Nicholson.

And now I read the reviews, I see that some others commenting in our group read of Tess of the D’Urbervilles have read and reviewed it too: Connie and Jim. My friends variously rate it between 1 and 4 stars.

So definitely one to look at later ... but that is wise advice David, so as not to spoil our read :)

Winter by Christopher Nicholson.

And now I read the reviews, I see that some others commenting in our group read of Tess of the D’Urbervilles have read and reviewed it too: Connie and Jim. My friends variously rate it between 1 and 4 stars.

So definitely one to look at later ... but that is wise advice David, so as not to spoil our read :)

Bionic Jean wrote: "What do we think to the mention of the young "upstart squire named d’Urberville", with a blind mother? We know who this must be! It did serve to clarify Angel’s beliefs about old families to us. Hi..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "What do we think to the mention of the young "upstart squire named d’Urberville", with a blind mother? We know who this must be! It did serve to clarify Angel’s beliefs about old families to us. Hi..."I agree with you about this comment — it is very foreboding, especially to Tess' future. I am enjoying your discussion about the religion of Angel's family because in the preceding chapter, I was very surprised at how they behaved towards the gifts that they had received, even if they could not use them. This is a paradox I have often found with those who say they are religious — and its possible this is why I am not a regular church goer....

Pamela wrote: "I was very surprised at how they behaved towards the gifts that they had received ..."

Great observation!

Yes, I too think a natural first thought is "How ungrateful!" if a gift is immediately passed on. Surely most of us do not blurt it out, even if we hate a gift we have received. We don't tell the (whole) truth, for fear of hurting the giver.

We know that the Clares are kind. So the only sense I can make of this, is that their religion makes them blinkered to any other views. They simply saw that a poor family had needs, and considered that they themselves did not need this extra food. They did not hold the consequence of Angel having to tell Mrs. Crick, and possibly hurt her feelings, to be of any account. Nor did they expect Angel to question what they had done.

I would like to think they would put kindness to everyone concerned first, but I believe they genuinely did not see it!

Great observation!

Yes, I too think a natural first thought is "How ungrateful!" if a gift is immediately passed on. Surely most of us do not blurt it out, even if we hate a gift we have received. We don't tell the (whole) truth, for fear of hurting the giver.

We know that the Clares are kind. So the only sense I can make of this, is that their religion makes them blinkered to any other views. They simply saw that a poor family had needs, and considered that they themselves did not need this extra food. They did not hold the consequence of Angel having to tell Mrs. Crick, and possibly hurt her feelings, to be of any account. Nor did they expect Angel to question what they had done.

I would like to think they would put kindness to everyone concerned first, but I believe they genuinely did not see it!

I find it interesting everyone knows Alec isn’t true nobility and has bought his title. It would seem to be a waste of money if it hasn’t brought him the respect he expected!

I find it interesting everyone knows Alec isn’t true nobility and has bought his title. It would seem to be a waste of money if it hasn’t brought him the respect he expected!I don’t know much about the differences between the different religious attitudes of the Clares but they all do seem to have a very fixed point of view and are quite judgemental of others which doesn’t bode well for Tess. It also makes me think that Angel will also be quite fixed in his views. To me he already has a picture of Tess in his mind (virginal, natural etc) and he hasn’t really got to know her as a person.

Janelle wrote: "I find it interesting everyone knows Alec isn’t true nobility and has bought his title. It would seem to be a waste of money if it hasn’t brought him the respect he expected!

Janelle wrote: "I find it interesting everyone knows Alec isn’t true nobility and has bought his title. It would seem to be a waste of money if it hasn’t brought him the respect he expected!I don’t know much abo..."

Good points, Janelle! Angel does have this unreal vision of Tess. He really sees her as a beautiful, desirable woman without knowing her background, what her expectations and beliefs are. That's a weak place to be.

Janelle, I have been thinking the same thing about Angel not really knowing Tess. Thanks for bringing that up!

I see how Angel really, really tries to be a good man, having Tess' wellbeing in mind, while he also tries to be practical about it. In this he indeed is a stark contrast to Alec. On the other hand he does not think to ask Tess if she wants to marry him, before discussing with his parents that he has her in mind for his wife. He already assumes she will say yes, just like Alec did.

Chapter 27: Summary

Angel goes down into the damp, fertile Froom Valley, and feels like he is experiencing life more fully than he did at home. He loves his family but he feels freed from a burden in returning to Talbothays. Everyone is having an afternoon nap at the dairy, but then the bell rings and Tess appears first.

Tess does not know Angel is back, and he admires the exuberance of Nature within her unconscious self:

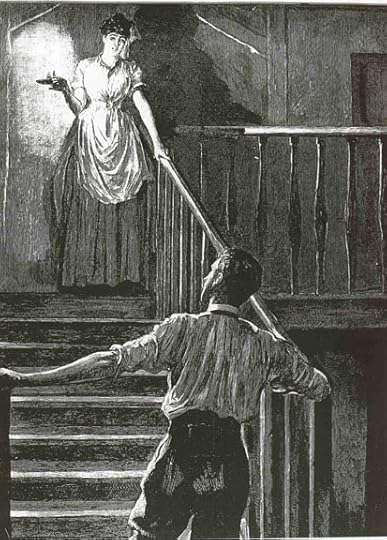

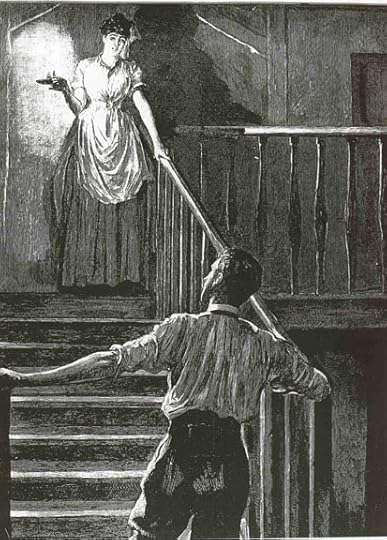

"Clare came down from the landing above in his shirt-sleeves, and put his arms across the stair-way." - D. A. Wehrschmidt - "The Graphic"

She suddenly notices Angel and then remembers their new relationship. Angel puts his arm around her and her heart beats excitedly, but she says she must do the skimming, as they are short-handed.

Angel offers to help her, and it is only the two of them skimming the milk. Tess experiences the afternoon as a hazy, joyful dream. Angel at last asks her to marry him, but frames the question in logical terms as a farmer needing a farmer’s wife, so that she does not feel he is too impulsive.

Tess suddenly seems to grow old and tired, and she says she can never be Angel’s wife. Her refusal breaks her own heart. Angel is amazed, and wants to know why she cannot marry him. She admits that she loves him, but feels “driven to subterfuge”, and gives the excuse that she is too low-born and his parents would disapprove. Even when Angel says he has already spoken to them she refuses, and he says he will wait, fearing that he has been too sudden in his proposal.

They go back to milk-skimming but Tess begins to cry. Angel tries to reassure her about his parents’ compassion, and asks about Tess’s religious beliefs. Her response is vague and sorrowful, but Angel thinks she is sincere enough that even his father could not disapprove.

Angel talks more about his visit, and then brings up his conversation with his father. He retells the story of the “lax young cynic” who insulted his father, and gives enough information for Tess to be able to tell it is Alec. The reminder of her past strengthens her in her refusal, but Angel does not notice her expression.

Tess runs back into the open field as if trying to escape her sadness. Now that Angel is back in the valley, he feels that marrying a dairymaid seems much more natural than marrying a woman like Mercy Chant.

Angel goes down into the damp, fertile Froom Valley, and feels like he is experiencing life more fully than he did at home. He loves his family but he feels freed from a burden in returning to Talbothays. Everyone is having an afternoon nap at the dairy, but then the bell rings and Tess appears first.

Tess does not know Angel is back, and he admires the exuberance of Nature within her unconscious self:

"Clare came down from the landing above in his shirt-sleeves, and put his arms across the stair-way." - D. A. Wehrschmidt - "The Graphic"

She suddenly notices Angel and then remembers their new relationship. Angel puts his arm around her and her heart beats excitedly, but she says she must do the skimming, as they are short-handed.

Angel offers to help her, and it is only the two of them skimming the milk. Tess experiences the afternoon as a hazy, joyful dream. Angel at last asks her to marry him, but frames the question in logical terms as a farmer needing a farmer’s wife, so that she does not feel he is too impulsive.

Tess suddenly seems to grow old and tired, and she says she can never be Angel’s wife. Her refusal breaks her own heart. Angel is amazed, and wants to know why she cannot marry him. She admits that she loves him, but feels “driven to subterfuge”, and gives the excuse that she is too low-born and his parents would disapprove. Even when Angel says he has already spoken to them she refuses, and he says he will wait, fearing that he has been too sudden in his proposal.

They go back to milk-skimming but Tess begins to cry. Angel tries to reassure her about his parents’ compassion, and asks about Tess’s religious beliefs. Her response is vague and sorrowful, but Angel thinks she is sincere enough that even his father could not disapprove.

Angel talks more about his visit, and then brings up his conversation with his father. He retells the story of the “lax young cynic” who insulted his father, and gives enough information for Tess to be able to tell it is Alec. The reminder of her past strengthens her in her refusal, but Angel does not notice her expression.

Tess runs back into the open field as if trying to escape her sadness. Now that Angel is back in the valley, he feels that marrying a dairymaid seems much more natural than marrying a woman like Mercy Chant.

Some nice points have been made, and I’m sure many people will want to comment on this chapter too :) So I’ll just add a couple of points about the writing.

Yet again we had a lush description of Nature’s bounty to begin; it was like the Garden of Eden - until the arrival of Tess, who was “yawning, and he saw the red interior of her mouth as if it had been a snake’s.”

That was when I first consciously thought “Garden of Eden”, although we then have it confirmed: “she regarded him as Eve at her second waking might have regarded Adam.”

We also read that her “most spiritual beauty bespeaks itself flesh; and sex takes the outside place in the presentation.”

It’s clear that sexual desire is as much Angel’s preoccupation as it was Alec’s, and both men said they would wait. Tess said to Alec she was dazzled by him for a while; with Angel, she is turning him down point blank. She sacrifices her feelings, but her behaviour is ambiguous, unless you are privy to her thoughts, as we are.

Then at the peak of her happiness Alec’s ghost cruelly comes back to haunt Tess. Will she ever escape her destiny? And who - or what - do you think the serpent represents?Is Alec the serpent? Or Tess herself? Or Angel’s lust? Or …

Yet again we had a lush description of Nature’s bounty to begin; it was like the Garden of Eden - until the arrival of Tess, who was “yawning, and he saw the red interior of her mouth as if it had been a snake’s.”

That was when I first consciously thought “Garden of Eden”, although we then have it confirmed: “she regarded him as Eve at her second waking might have regarded Adam.”

We also read that her “most spiritual beauty bespeaks itself flesh; and sex takes the outside place in the presentation.”

It’s clear that sexual desire is as much Angel’s preoccupation as it was Alec’s, and both men said they would wait. Tess said to Alec she was dazzled by him for a while; with Angel, she is turning him down point blank. She sacrifices her feelings, but her behaviour is ambiguous, unless you are privy to her thoughts, as we are.

Then at the peak of her happiness Alec’s ghost cruelly comes back to haunt Tess. Will she ever escape her destiny? And who - or what - do you think the serpent represents?Is Alec the serpent? Or Tess herself? Or Angel’s lust? Or …

I like the way the chapter is top and tailed by the purity and freedom of agricultural life praised over religious repression or middle-class prudishness. We see at both points that Angel is also a young man rebelling against his parents’ world, comparing his stifling home town to Tess’s unencumbered natural purity.

Right at the end we see Tess back in her element, gamboling without care, in the natural environment, the:

“reckless, unchastened motion of women accustomed to unlimited space—in which they abandoned themselves to the air”.

She seems to have recovered instantly, as a creature of nature would, and be truly happy. No wonder Angel idealises her, and cannot imagine his innocent Nature-girl having any kind of real objection to their marriage.

Over to you :)

Right at the end we see Tess back in her element, gamboling without care, in the natural environment, the:

“reckless, unchastened motion of women accustomed to unlimited space—in which they abandoned themselves to the air”.

She seems to have recovered instantly, as a creature of nature would, and be truly happy. No wonder Angel idealises her, and cannot imagine his innocent Nature-girl having any kind of real objection to their marriage.

Over to you :)

I like to make note of one sentence in each chapter that really strikes me, and it was no contest in Chapter 27: "She was yawning, and he saw the red interior of her mouth as if it had been a snake's." Just amazing, particularly given the sharp contrast between that and everything Angel had thought of Tess previously. Speaking of snakes, there's the often quoted anecdote of a (non-threatening) snake being found in Hardy's crib when he was a baby, and the death of Mrs. Yeobright following a snakebite in "The Return of the Native." Any other Hardy-associated snakes I'm missing (other then Sgt. Troy)?

I like to make note of one sentence in each chapter that really strikes me, and it was no contest in Chapter 27: "She was yawning, and he saw the red interior of her mouth as if it had been a snake's." Just amazing, particularly given the sharp contrast between that and everything Angel had thought of Tess previously. Speaking of snakes, there's the often quoted anecdote of a (non-threatening) snake being found in Hardy's crib when he was a baby, and the death of Mrs. Yeobright following a snakebite in "The Return of the Native." Any other Hardy-associated snakes I'm missing (other then Sgt. Troy)?

Nice connection with Thomas Hardy as a baby, Keith. It's good to see you back - there's lots to read in our discussions :)

Thanks for picking up on the quotation I selected (just 2 comments before yours) ... I'm thinking now that perhaps that sentence stood out to everyone, not just me, and that it must be a deliberate change of tone by by Thomas Hardy to a sinister, jarring one.

So to repeat my question, who/what do you think the serpent represents? And now, since your observations, do you think it has any personal significance for Thomas Hardy?

But I'd prefer not to comment on The Return of the Native, or another character from a different novel you mention, in case it spoils anything. Not everyone here knows them all. Spoiler tags can be used of course though, for any more ideas please.

Thanks for picking up on the quotation I selected (just 2 comments before yours) ... I'm thinking now that perhaps that sentence stood out to everyone, not just me, and that it must be a deliberate change of tone by by Thomas Hardy to a sinister, jarring one.

So to repeat my question, who/what do you think the serpent represents? And now, since your observations, do you think it has any personal significance for Thomas Hardy?

But I'd prefer not to comment on The Return of the Native, or another character from a different novel you mention, in case it spoils anything. Not everyone here knows them all. Spoiler tags can be used of course though, for any more ideas please.

Sorry about the spoiler -- I tend to assume everyone here has read the Big 5 (plus, often, The Woodlanders), which of course is not necessarily so. As for the snake's significance, I'll leave that to others!

Sorry about the spoiler -- I tend to assume everyone here has read the Big 5 (plus, often, The Woodlanders), which of course is not necessarily so. As for the snake's significance, I'll leave that to others!

I thought the snake represented temptation since Hardy included the Adam and Eve reference. Angel is looking at Tess as a sexual temptation, although he is treating her with respect and asks her to marry him.

I thought the snake represented temptation since Hardy included the Adam and Eve reference. Angel is looking at Tess as a sexual temptation, although he is treating her with respect and asks her to marry him.Snakes are also sometimes associated with fertility since they shed their skins and are "reborn." There have been so many mentions of Tess that involve nature that this meaning could also apply.

Bionic Jean wrote: "This Phase is titled “The Consequence”, and so far all we have seen is Angel’s wrestling with his conscience, and trying to persuade his family and himself that he could marry Tess. Where could we ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "This Phase is titled “The Consequence”, and so far all we have seen is Angel’s wrestling with his conscience, and trying to persuade his family and himself that he could marry Tess. Where could we ..."Jean

Ah, you ask where we could go from here? I think I’ll go back to the beginning of the novel. There, we find Tess’s father learning of, and then more eagerly clinging to, the fact his decedents are highly born. They may well be the answer to the family’s circumstances of poverty so Tess is obligated to seek her family’s security.

In this chapter we get to see Angel’s family who are sincerely concerned for their son’s future. What a difference the Clare family is. Angel’s father has saved for his son’s future. He and his wife are sincerely concerned for the choices in life Angel will make. While they may not wholeheartedly agree with Angel thy both respect him and support him. The two families present very different aspirations for their children.

In Chapter 26 Hardy reintroduces the d’Urberville family. They are the fulcrum that will balance, or perhaps topple, our story. We learn that Alec and Reverend Clare have met. We have further confirmation that Alec is an unrepentant human being. We now know that Angel is aware of the d’Uberville family and Alec, but obviously unaware of his past with Tess.

The three principle families are now in play in the novel. Angel, Alec and Tess are the principle characters. What Fates will Hardy introduce to these characters?

Bionic Jean wrote ...their religion makes them blinkered to any other views

Bionic Jean wrote ...their religion makes them blinkered to any other viewsIn his treatment of Mr. Clare, it seems to me that even though Hardy was being bluntly critical of the unbending, myopic views of the clergy in his day, he was at the same time cutting them a bit of slack: Angel’s parents are unable to grasp the importance of a farmer choosing a wife who is willing and able to be a full and active partner in the enterprise; they believe that a wife’s religious beliefs are all that is necessary to sustain her. But they are not being deliberately obtuse; they have simply never lived outside of the confines of the ecclesiastic life, the realities of a farmer’s life are completely unknown to them. In a way, the Clares are also victims of their own fate. It’s impossible for them to change their attitudes and therefore the future path of their family is predetermined.

Far from moving the story along, chapters 25 & 26 have only tightened the knots within which both Angel and Tess are bound. By turning away from the ecclesiastic life that dominates all aspects of his family’s life, Angel has sought to free himself of strictures surrounding both his beliefs and his life choices. But it soon becomes clear that he cannot entirely escape without alienating his parents and siblings. Nor can Tess escape the “consequences” of her past misfortune. And Alec D’Urberville’s name and sordid reputation have re-surfaced and found their way round to the Clare family; the knowledge of his presence must continue to haunt Tess. Hardy, in his true fashion, has seen to it that there can be no escape from their “fate”.

The phrase “the red interior of her mouth as if it had been the interior of a snake’s mouth” jumped out to me as well. Looking at the phrase I noticed that Hardy used the phrase ‘as if’ rather than directly imploring a simile or a metaphor. I interpret the phrase ‘as if’’ to mean ‘could have been. That makes the phrase less a direct comparison and more a possibility.

The phrase “the red interior of her mouth as if it had been the interior of a snake’s mouth” jumped out to me as well. Looking at the phrase I noticed that Hardy used the phrase ‘as if’ rather than directly imploring a simile or a metaphor. I interpret the phrase ‘as if’’ to mean ‘could have been. That makes the phrase less a direct comparison and more a possibility. Is Tess the snake who has charmed both Alec and an Angel? In Alec’s case it was he who was constantly portrayed wreathed in smoke from a glowing red tipped cigar. To me, he is the snake who entered the Eden of Tess’s life. As for Angel, well, we have his name to mark him. He and Tess inhabit a semi-edenic space. I think Tess may be a tempter, but she is not a snake.

Also, is anyone else like me in not knowing anything about skimming milk. Hardy spends much time and detail concerning this activity, mentioning the equipment used, the reasons for and the result of the action. I wonder if a better understanding of skimming would yield a better understanding of what was occurring between Tess and Angel in this chapter.

Jantine wrote: "I see how Angel really, really tries to be a good man, having Tess' wellbeing in mind, while he also tries to be practical about it. In this he indeed is a stark contrast to Alec. On the other hand he does not think to ask Tess if she wants to marry him, before discussing with his parents that he has her in mind for his wife. He already assumes she will say yes, just like Alec did.

Jantine wrote: "I see how Angel really, really tries to be a good man, having Tess' wellbeing in mind, while he also tries to be practical about it. In this he indeed is a stark contrast to Alec. On the other hand he does not think to ask Tess if she wants to marry him, before discussing with his parents that he has her in mind for his wife. He already assumes she will say yes, just like Alec did.I love the character of Angel and would be happiest if I knew that Angel & Tess would live "happy ever after" but I'm afraid that this is not that type of novel. But I digress, I wanted to say, that don't you think it was fairly normal during those times to discuss possible marriage partners with one's parent? As we know many marriages were arranged for monetary and/or property gain, although this would not be the case for Angel choosing Tess. He clearly is in love with her and yet makes a practical choice as well for a farmer's life. He would prefer to have his parents' approval, it makes acceptance for Tess and life in general so much easier.

Each time Tess and Angel converse, they are at cross purposes; being unaware of Tess's personal tragedy, Angel is unable to interpret her reaction to his advances. She appears to be such a wholesome, uncomplicated child of nature and yet she turns away his protestations of love and sorrowfully refuses his offer of marriage. She is not the sort of girl to be coy. I've encountered this sort of miscommunication elsewhere in Hardy's work, it's one of his favorite dramatic devices (no spoilers here).

Each time Tess and Angel converse, they are at cross purposes; being unaware of Tess's personal tragedy, Angel is unable to interpret her reaction to his advances. She appears to be such a wholesome, uncomplicated child of nature and yet she turns away his protestations of love and sorrowfully refuses his offer of marriage. She is not the sort of girl to be coy. I've encountered this sort of miscommunication elsewhere in Hardy's work, it's one of his favorite dramatic devices (no spoilers here).The simile of the red interior of her mouth as if it had been a snake's is so jarring that it can only have been intentional on Hardy's part. The snake allusion cannot signify evil or deception on Tess's part, she is such a blameless person. I suspect it simply represents Tess's fate, her downfall. And that Angel, having momentarily noticed it, has been sent a message that he cannot yet see the meaning of. He too will suffer the consequences.

I think the snake allusion is about Angel’s lust for Tess. That whole paragraph is really about his lust. There is a second snake comparison in the next sentence, where Tess’s hair is a “coiled-up cable” on top of her head. At least for me, that brought another snake image to mind. I think Tess is an unwitting temptress. I mean she doesn’t try to exude sexuality, she just does.

In Genesis, Adam and Eve are kicked out of Eden when they eat from the tree of knowledge and realize they are naked. Of course, they’ve been naked the whole time, but what the apple awakens in them is sexual awareness, and so they cover themselves. They have lost their innocence and as a consequence they have to leave Eden. It is the snake tempting Eve that begins all that. Maybe this is the beginning of something similar for Tess and Angel. That ties in nicely with the title of this Phase - “The Consequence”.

In Genesis, Adam and Eve are kicked out of Eden when they eat from the tree of knowledge and realize they are naked. Of course, they’ve been naked the whole time, but what the apple awakens in them is sexual awareness, and so they cover themselves. They have lost their innocence and as a consequence they have to leave Eden. It is the snake tempting Eve that begins all that. Maybe this is the beginning of something similar for Tess and Angel. That ties in nicely with the title of this Phase - “The Consequence”.

Chris wrote: "Jantine wrote: "I see how Angel really, really tries to be a good man, having Tess' wellbeing in mind, while he also tries to be practical about it. In this he indeed is a stark contrast to Alec. O..."

That is true Chris. It is part of the overall picture though, together with chapter 27 where Angel doesn't seem to grasp that Tess' 'no' actually means 'no'.

That is true Chris. It is part of the overall picture though, together with chapter 27 where Angel doesn't seem to grasp that Tess' 'no' actually means 'no'.

Books mentioned in this topic

Under the Greenwood Tree (other topics)Measure for Measure (other topics)

Romeo and Juliet (other topics)

Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing (other topics)

A Tale of Two Cities (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Thomas Hardy (other topics)Thomas Hardy (other topics)

Thomas Hardy (other topics)

William Shakespeare (other topics)

Lord Byron (other topics)

More...

Phase the Fourth: The Consequence: Chapters 25 - 34

Gertrude Bugler - Thomas Hardy's inspiration for Tess