Works of Thomas Hardy discussion

This topic is about

The Mayor of Casterbridge

The Mayor of Casterbridge

>

The Mayor of Casterbridge: 2nd thread: Chapters 10 - 17

"The Ghost"

"The Ghost""Mrs. Henchard was so pale that the boys called her “The Ghost.” Sometimes Henchard overheard this epithet when they passed together along the Walks—as the avenues on the walls were named—at which his face would darken with an expression of destructiveness towards the speakers ominous to see; but he said nothing."

"The Ghost" has an ominous sound to it. Hardy is using words like fragile and pale when he writes about her. She's had a hard life so I hope she has some happy years in a comfortable situation ahead of her.

Thank you Bridget for conveying Jean's posts!

Thank you Bridget for conveying Jean's posts!Great point about the Ghost, Connie! I also noticed how ectoplasmic Susan seems to be, and somehow difficult to characterise.

I noticed the sturdiness of the furniture in Henchard's home (mentioned before), and of the pieces of furniture he has provided for the cottage. It all speaks of a showy affluence. This seems to be disproportionate in Susan's opinion:

"And she looked at him and at his dress as a man of affluence, and at the furniture he had provided for the room— ornate and lavish to her eyes."

The narrative voice described Henchard as "red and black", and mentioned his ambiguous gaze, oscillating between satisfaction and "fiery disdain".

Gossips: a great description of conversation in little towns. Gossips usually need little material to grow and spread, then, what about "real" secrets?...

I also noticed that Farfrae was the groomsman (and secret bearer). This shows that Henchard is really a lonely man: no relatives, no close friends, although he has obviously been in Casterbridge for years.

Henchard was focused on "making amends to Susan", as already mentioned in the closing lines of chapter 12, and occurring again here, which corroborated the sense of duty Jean mentioned.

This was a tough chapter to read: I could so much emphasize with Susan who is a quite overwhelmed by what is happening, the cottage, the furniture and Henchard's attention to her. It feels like he is rushing her into this action which may assuage his guilt but what a cost.

This was a tough chapter to read: I could so much emphasize with Susan who is a quite overwhelmed by what is happening, the cottage, the furniture and Henchard's attention to her. It feels like he is rushing her into this action which may assuage his guilt but what a cost.It reminds me of a couple who really should divorce but stay together for the sake of the child. It never works and the child is the one who is hurt by it.

And what happens if Elizabeth-Jane marries? Without her, what will happen? Will Henchard go back to drinking, take on a mistress?

And, like Claudia, I can't see 'the Jersey belle' accepting dismissal with a payment. Reckoning will be happening soon.

I agree this was a tough chapter. I was a little surprised at the emphasis put on Susan's appearance: poor, fragile, ghostly, "so little." I feel like this reflects her unhappiness at this time--she's like the opposite of glowing. I have to agree with Nance Mockrige, that "She'll wish her cake dough afore she's done of him," which my notes translated as wishing she could undo what she'd done.

I agree this was a tough chapter. I was a little surprised at the emphasis put on Susan's appearance: poor, fragile, ghostly, "so little." I feel like this reflects her unhappiness at this time--she's like the opposite of glowing. I have to agree with Nance Mockrige, that "She'll wish her cake dough afore she's done of him," which my notes translated as wishing she could undo what she'd done.

Well now, I have attended a few marriages in my time but cannot recall any that were as cold, heartless and bloodless as this one.

Well now, I have attended a few marriages in my time but cannot recall any that were as cold, heartless and bloodless as this one.Hardy makes sure the reader sees Susan and a ghost, a ‘skellinton,’ a wisp of smoke. With such an overriding tone of fragility I wonder if Hardy is signalling that Susan’s health is failing. How ironic (and perhaps typical of Hardy) that just when the external desires of Susan such as a home, financial security, and a harbour for her child are secured by marriage, she will be unable to enjoy them. On more than one occasion recently we have been told Susan is fading away. Will death soon tragically embrace her?

As for Henchard, it seems Hardy continually reminds us that Henchard is, first and foremost, a man of business. We have identified this trait before but there were three more examples that I found this chapter. The first is now Hardy characterizes Henchard’s actions as ‘restitutory acts’ rather than acts of kindness, love, or empathy. I also found the phrase ‘rough benignity’ to describe Henchard’s business-like determination to be a very effective oxymoron. The last was how Hardy commented that ‘there’s a blue-beardy look about Henchard. The reference to the legend of Bluebeard presents some disquiet. Bluebeard collected and killed his wives. They were transactions rather than emotional helpmates.

Thanks Peter for mentioning Bluebeard (I totally forgot to do so). The most famous version by Charles Perrault, La Barbe Bleue, aka Barbe-Bleue, has multiple layers of interpretation (the consequences of curiosity, but also incest, etc.) discussed by Bruno Bettelheim and many others.

Thanks Peter for mentioning Bluebeard (I totally forgot to do so). The most famous version by Charles Perrault, La Barbe Bleue, aka Barbe-Bleue, has multiple layers of interpretation (the consequences of curiosity, but also incest, etc.) discussed by Bruno Bettelheim and many others. Michael Henchard has something of an ogre about him - his former excesses in drinking, something in his attitude, his laugh. The red and black, rouge et noir, allusions hint at his black hair and red complexion described earlier.

Before I make my comments, I wanted you all to know I've posted in the Kings Arm Chat thread about why Jean isn't commenting today. If you are curious, please read my post there.

Moving on . . .

Thanks Peter for the info about Bluebeard. I picked up on Hardy's reference, but I didn't know Bluebeard collected and killed wives. I didn't know about the incest that Claudia mentioned either. I thought it was ominous using a pirate for comparison, but now I'm even more concerned for Susan as she does seem to be "fading away", which you all pointed out in your excellent comments.

Pamela, comparing this marriage to couples who stay together for the kids, is spot on. And Kathleen, thank you for talking about the cake/dough reference. I had been scratching my head trying to figure that out, and I think your interpretation is correct.

Connie, thank you so much for grabbing the "carrion crow" reference. It happened so quickly that once again I would have missed the bird connection without your help!

Moving on . . .

Thanks Peter for the info about Bluebeard. I picked up on Hardy's reference, but I didn't know Bluebeard collected and killed wives. I didn't know about the incest that Claudia mentioned either. I thought it was ominous using a pirate for comparison, but now I'm even more concerned for Susan as she does seem to be "fading away", which you all pointed out in your excellent comments.

Pamela, comparing this marriage to couples who stay together for the kids, is spot on. And Kathleen, thank you for talking about the cake/dough reference. I had been scratching my head trying to figure that out, and I think your interpretation is correct.

Connie, thank you so much for grabbing the "carrion crow" reference. It happened so quickly that once again I would have missed the bird connection without your help!

I thought for a wedding chapter, the tone was very unhappy. The ending really brought that home for me when Solomon gossips about a man who dropped dead the day before. I found his comment a bit jarring. I wasn't expecting the townspeople to switch from gossiping a wedding to gossiping about a death. And it left me with a feeling of foreboding.

Bridget wrote: I didn't know about the incest that Claudia mentioned either.

Bridget wrote: I didn't know about the incest that Claudia mentioned either.It is more a matter of interpretation of the fact that Barbe-Bleue wants to marry one of his neighbour's daughters, which has been interpreted by some as transgression of the tabu of endogamy. Both daughters are scared or disgusted by him but, because he is behaving nicely and courteously, one of them accepts him. Anyway, as many fairy tales, it is "ein weites Feld" (says Herr von Briest in Effi Briest by Theodor Fontane).

Claudia wrote: "Bridget wrote: I didn't know about the incest that Claudia mentioned either.

It is more a matter of interpretation of the fact that Barbe-Bleue wants to marry one of his neighbour's daughters, whi..."

Ah, I see. Thanks for the clarification, Claudia!

It is more a matter of interpretation of the fact that Barbe-Bleue wants to marry one of his neighbour's daughters, whi..."

Ah, I see. Thanks for the clarification, Claudia!

Chapter 14

Both Susan and Elizabeth-Jane flourish once they move into Henchard’s home. He provides for them, improving his own home, and buying things his wife and daughter desire. Elizabeth-Jane blooms and beomes more beautiful as the lines on her brow, and cares of poverty vanish. She does not make a fool of herself by dressing extravagantly with her new wealth and position, but instead continues to be modest, fearful that a dramatic display of her new situation would only tempt Providence to cast her and her mother down again.

One morning at breakfast, Henchard comments upon Elizabeth-Jane’s hair, which is light brown. He says that Susan had once remarked that her daughter’s hair would turn out black. Susan gives him a startled look, and once Elizabeth-Jane has left the room, Henchard exclaims that he almost forgot their agreement and mistakenly revealed his and Susan’s true connection. He repeats that Elizabeth-Jane’s hair had once appeared like it would be darker, and Susan looks uneasy.

Henchard then shares with Susan that he would like to have Elizabeth-Jane called Miss Henchard rather than Miss Newson. Susan protests slightly at first, but then agrees with Henchard. However, when Susan goes to Elizabeth-Jane and tells her of Henchard’s proposal to change her last name, she asks her daughter whether or not she too feels this to be a slight against the deceased Newson. Elizabeth-Jane asks Henchard if the name change matters greatly to him. Henchard quickly dismisses his commitment to the change, saying Elizabeth-Jane should not do it to please him, and the matter is not discussed again.

Meanwhile, Henchard’s business thrives with Farfrae’s management. Farfrae meticulously replaces Henchard’s method of making verbal promises and remembering everything with ledgers and written agreements. Henchard spends a large amount of time with the young man and considers him a close companion. Elizabeth-Jane frequently watches the pair in the yard at work from her bedroom window.

Elizabeth-Jane also notes how Farfrae looks at her and her mother, as they walk together. She is slightly disappointed and confused to see that Farfrae looks most at her mother. She dismisses this information, not suspecting the truth of her parents’ shared past or Farfrae’s knowledge of this.

A street consisting of farmer’s homesteads makes up the Durnover end of Casterbridge where those who farm corn on the uplands side of the town live. These are the men with whom Henchard primarily does business. One day, Elizabeth-Jane receives a note by hand asking her come at once to a specific granary in Durnover. She thinks the note must have something to do with Henchard’s business in that area.

Elizabeth-Jane arrives at the granary and waits, only to see Farfrae appear. She hides in the granary itself, not wishing to meet him directly, out of shyness. However, he too stops there to wait, drawing out of his pocket a note identical to her note. The situation, Elizabeth-Jane realizes, is very awkward. She does not want to reveal her hiding place as more and more time passes. Farfrae, however, hears her move in the granary and ascends the steps to see her there.

Elizabeth-Jane assumes Farfrae had arranged to meet her and she shows him the note she received. He shows her the similar note that he received and the pair realizes that some third person must be wishing to see them both and decides to wait.

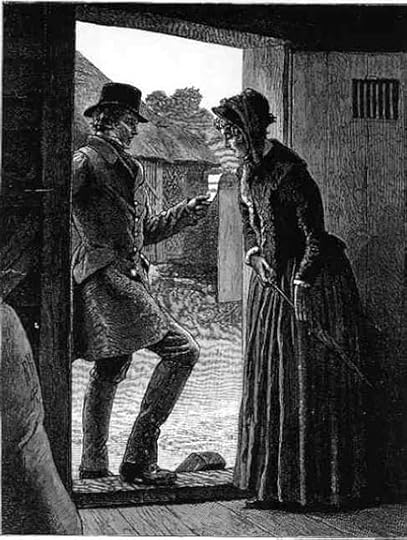

“Then it’s somebody wanting to see us both” by Robert Barnes - 6th February 1886

Eventually the two young people begin a conversation. Elizabeth-Jane asks about Scotland and mentions the song Farfrae sang at The King of Prussia. Farfrae says that he does not long to return to Scotland, despite his emotion while singing of his homeland.

Farfrae delicately points out that Elizabeth-Jane’s dress is covered in wheat husks from the granary. He offers his assistance and blows the wheat husks from her clothes and hair. Farfrae no longer seems in a rush to leave the granary. Elizabeth-Jane, however, refuses his offer to get her an umbrella, and leaves promptly. Farfrae looks after her, whistling, “As I came down through Cannobie.”

Both Susan and Elizabeth-Jane flourish once they move into Henchard’s home. He provides for them, improving his own home, and buying things his wife and daughter desire. Elizabeth-Jane blooms and beomes more beautiful as the lines on her brow, and cares of poverty vanish. She does not make a fool of herself by dressing extravagantly with her new wealth and position, but instead continues to be modest, fearful that a dramatic display of her new situation would only tempt Providence to cast her and her mother down again.

One morning at breakfast, Henchard comments upon Elizabeth-Jane’s hair, which is light brown. He says that Susan had once remarked that her daughter’s hair would turn out black. Susan gives him a startled look, and once Elizabeth-Jane has left the room, Henchard exclaims that he almost forgot their agreement and mistakenly revealed his and Susan’s true connection. He repeats that Elizabeth-Jane’s hair had once appeared like it would be darker, and Susan looks uneasy.

Henchard then shares with Susan that he would like to have Elizabeth-Jane called Miss Henchard rather than Miss Newson. Susan protests slightly at first, but then agrees with Henchard. However, when Susan goes to Elizabeth-Jane and tells her of Henchard’s proposal to change her last name, she asks her daughter whether or not she too feels this to be a slight against the deceased Newson. Elizabeth-Jane asks Henchard if the name change matters greatly to him. Henchard quickly dismisses his commitment to the change, saying Elizabeth-Jane should not do it to please him, and the matter is not discussed again.

Meanwhile, Henchard’s business thrives with Farfrae’s management. Farfrae meticulously replaces Henchard’s method of making verbal promises and remembering everything with ledgers and written agreements. Henchard spends a large amount of time with the young man and considers him a close companion. Elizabeth-Jane frequently watches the pair in the yard at work from her bedroom window.

Elizabeth-Jane also notes how Farfrae looks at her and her mother, as they walk together. She is slightly disappointed and confused to see that Farfrae looks most at her mother. She dismisses this information, not suspecting the truth of her parents’ shared past or Farfrae’s knowledge of this.

A street consisting of farmer’s homesteads makes up the Durnover end of Casterbridge where those who farm corn on the uplands side of the town live. These are the men with whom Henchard primarily does business. One day, Elizabeth-Jane receives a note by hand asking her come at once to a specific granary in Durnover. She thinks the note must have something to do with Henchard’s business in that area.

Elizabeth-Jane arrives at the granary and waits, only to see Farfrae appear. She hides in the granary itself, not wishing to meet him directly, out of shyness. However, he too stops there to wait, drawing out of his pocket a note identical to her note. The situation, Elizabeth-Jane realizes, is very awkward. She does not want to reveal her hiding place as more and more time passes. Farfrae, however, hears her move in the granary and ascends the steps to see her there.

Elizabeth-Jane assumes Farfrae had arranged to meet her and she shows him the note she received. He shows her the similar note that he received and the pair realizes that some third person must be wishing to see them both and decides to wait.

“Then it’s somebody wanting to see us both” by Robert Barnes - 6th February 1886

Eventually the two young people begin a conversation. Elizabeth-Jane asks about Scotland and mentions the song Farfrae sang at The King of Prussia. Farfrae says that he does not long to return to Scotland, despite his emotion while singing of his homeland.

Farfrae delicately points out that Elizabeth-Jane’s dress is covered in wheat husks from the granary. He offers his assistance and blows the wheat husks from her clothes and hair. Farfrae no longer seems in a rush to leave the granary. Elizabeth-Jane, however, refuses his offer to get her an umbrella, and leaves promptly. Farfrae looks after her, whistling, “As I came down through Cannobie.”

A little more ...

"A Martinmas Summer" - St. Martin's Day is on November 11th, so this means there was unusually warm Autumn Weather.

"A Martinmas Summer" - St. Martin's Day is on November 11th, so this means there was unusually warm Autumn Weather.

**Again, all these posts are from, Jean. I am merely the copy and paste gal today :-)

We see the dramatic impact their increase in wealth has on both Susan and Elizabeth-Jane. Their physical appearances, as well as their possessions, improves. However Elizabeth-Jane is wary of this new wealth because she is familiar with loss and poverty. Her unwillingness to indulge displays her prudence and her modesty, though her diffidence also stops her from seizing what she wants.

Through this minor slip-up about the colour of her hair, the truth is almost revealed to Elizabeth-Jane. We see the difficulty of hiding such complex secrets, several of which we’ve been privy to so far. But this comment:

“And the same uneasy expression came out on her face, to which the future held the key. It passed as Henchard went on"

gave me pause for thought. There is foreshadowing here, but we can only speculate what this is.

Elizabeth-Jane is not suspicious about obeying the request of a note that she thinks has to do with Henchard’s business.

Farfrae’s meticulous management improves Henchard’s business and demonstrates that he is better at business. Should Henchard feel threatened or worried about this? Elizabeth-Jane finds Farfrae alluring, but is so modest that nothing comes of it. Farfrae is more curious about Susan than about Elizabeth-Jane because of the secret he knows. It is this disappointment at his lack of interest in her which reveals to us Elizabeth-Jane’s interest in Farfrae.

Her instinctual response to Farfrae’s appearance is to hide, which shows both her shyness and her particular shyness of Farfrae. Farfrae, however, does not exhibit this same shyness, and approaches her in the granary.

The pair believe they must be waiting for some third person, the sender of the notes, but as they wait, they begin to get to know each other. They are able to speak about personal matters, such as Farfrae’s emotions about his homeland, despite his assurance that he doesn’t plan to return there.

Farfrae’s action of blowing the wheat husks from Elizabeth-Jane’s dress is both intimate, and able to be interpreted as subtly sexual. Elizabeth-Jane’s quick departure reflects her embarrassment, and Farfrae’s hesitation shows his newfound interest in the girl.

We see the dramatic impact their increase in wealth has on both Susan and Elizabeth-Jane. Their physical appearances, as well as their possessions, improves. However Elizabeth-Jane is wary of this new wealth because she is familiar with loss and poverty. Her unwillingness to indulge displays her prudence and her modesty, though her diffidence also stops her from seizing what she wants.

Through this minor slip-up about the colour of her hair, the truth is almost revealed to Elizabeth-Jane. We see the difficulty of hiding such complex secrets, several of which we’ve been privy to so far. But this comment:

“And the same uneasy expression came out on her face, to which the future held the key. It passed as Henchard went on"

gave me pause for thought. There is foreshadowing here, but we can only speculate what this is.

Elizabeth-Jane is not suspicious about obeying the request of a note that she thinks has to do with Henchard’s business.

Farfrae’s meticulous management improves Henchard’s business and demonstrates that he is better at business. Should Henchard feel threatened or worried about this? Elizabeth-Jane finds Farfrae alluring, but is so modest that nothing comes of it. Farfrae is more curious about Susan than about Elizabeth-Jane because of the secret he knows. It is this disappointment at his lack of interest in her which reveals to us Elizabeth-Jane’s interest in Farfrae.

Her instinctual response to Farfrae’s appearance is to hide, which shows both her shyness and her particular shyness of Farfrae. Farfrae, however, does not exhibit this same shyness, and approaches her in the granary.

The pair believe they must be waiting for some third person, the sender of the notes, but as they wait, they begin to get to know each other. They are able to speak about personal matters, such as Farfrae’s emotions about his homeland, despite his assurance that he doesn’t plan to return there.

Farfrae’s action of blowing the wheat husks from Elizabeth-Jane’s dress is both intimate, and able to be interpreted as subtly sexual. Elizabeth-Jane’s quick departure reflects her embarrassment, and Farfrae’s hesitation shows his newfound interest in the girl.

Great summary and interpretation, Jean!

Great summary and interpretation, Jean!I also underlined the same passage “And the same uneasy expression came out on her face, to which the future held the key. It passed as Henchard went on" for the same reason!

Not telling the truth may prove to be a hard job. Someone said recently that lying requires a good memory.

The motif of Elizabeth-Jane looking at Farfrae and Henchard through the window, as an observer, on-looker and watcher, is recurring again!

Wow! This is an incredibly rich chapter of character development, plot advancement, foreshadowing and it even ends with a song! Love it!

Wow! This is an incredibly rich chapter of character development, plot advancement, foreshadowing and it even ends with a song! Love it!Claudia, I find the motif of Elizabeth-Jane as the observer very strongly reinforced in this chapter on more than one occasion. What I’d like to do is link the concept of the watcher to the Robert Barnes illustration.

Windows and doorways serve as a key symbol in both art and literature. They represent a liminal space, a zone of transition, a projection of what is both an immediate moment and a view into the future.

The Barnes illustration is an excellent example. Elizabeth-Jane stands within the barn, in partial shadow. Her hands are held down on her sides, her head is bowed and she is portrayed as leaning slightly forward. We do not see a note in her hand. Farfrae stands outside the door to the barn but he is portrayed as leaning forward. In his hand is seen a piece of paper. What is significant in his pose is that his foot is positioned forward on the doorstep. He is in the act of advancing toward Elizabeth-Jane, of entering through the door and thus into her space. The act of blowing wheat from Elizabeth-Jane’s dress when linked to Farfrae’s physical position in this illustration furthers the suggestion of a possible intimacy.

Within the frame of the illustration we have Farfrae and Elizabeth-Jane framed a second time by the door frame. We have, to a degree, a picture with a picture.

Such interpretations are of course, suggestions and certainly can be speculative. I think, however, that artists rely on tropes and that this illustration is an excellent representation and moves the subplot of Elizabeth-Jane forward to our first intimate moment when Elizabeth-Jane is more than an observer. She is now a participant with Farfrae in what may unfold in future chapters. This illustration is a proleptic moment in the novel.

Peter wrote: Windows and doorways serve as a key symbol in both art and literature. They represent a liminal space, a zone of transition, a projection of what is both an immediate moment and a view into the future.

Peter wrote: Windows and doorways serve as a key symbol in both art and literature. They represent a liminal space, a zone of transition, a projection of what is both an immediate moment and a view into the future.Thank you for this thorough explanation, Peter! This corroborates the thin wall in chapter 7, through which the two ladies listened to Henchard's conversation with Farfrae at the Three Mariners Inn. Not only was the wall thin, but there was evidence of a door beneath the wallpaper! We definitely need to keep windows and doorways in mind.

Thanks also for enhancing Elizabeth-Jane's role as an observer but now also as a participant. She was nearly absent as an actor from the last two chapters - but nevertheless mentioned. Now she is virtually centre stage while her mother seems to be gradually shifting to the background - formerly described as a ghost. The hair colour matter is puzzling, and Elizabeth-Jane's sharpness of mind did not miss that.

Interestingly, Barnes has illustrated the eavesdropping scene through a wallpapered door in chapter 7 and now the granary scene in a doorway.

I also noticed at least twice another both visual and narrative motif: a protagonist is watching another walk away, until he/she is but a small figure and vanished from the picture. The architect Thomas Hardy was certainly very familiar with the technique of perspective drawing.

Here, Farfrae is watching Elizabeth-Jane go. "Farfrae walked slowly after, looking thoughtfully at her diminishing figure...".

The closing lines of chapter 11 described, albeit less technically, how Henchard was watching Susan go: by the time he reached his door he was almost upon the heels of the unconscious woman from whom he had just parted. He watched her up the street, and turned into his house.

Claudia

ClaudiaYes indeed. There is a subtle yet incisive power in Hardy’s writing. I am glad we have such keen intuitive group members. There has not been a single chapter where either the opening commentary or the group’s analysis — and quite often both! —has not made me say to myself that I either missed something entirely or was offered a fresh perspective through a member's response.

Bridget, you are of course way more than a copy and paste gal, but thank you for keeping us going in Jean's absence!

Bridget, you are of course way more than a copy and paste gal, but thank you for keeping us going in Jean's absence!I appreciate Claudia and Peter's insights, particularly the meaning of doors and windows. My main takeaway from this intriguing chapter was the two pretty strong hints we were given--the hair color comment and also Farfrae's focus on Susan--that could mean more secrets and trouble to come.

Kathleen wrote: "Bridget, you are of course way more than a copy and paste gal, but thank you for keeping us going in Jean's absence!

Kathleen wrote: "Bridget, you are of course way more than a copy and paste gal, but thank you for keeping us going in Jean's absence!I appreciate Claudia and Peter's insights, particularly the meaning of doors an..."

This is an interesting chapter — I noted the hair color comment but was much more stricken by Henchard's comments to Susan that Elizabeth-Jane's last name should be changed — and yet, he acted as if it wasn't important to him when Elizabeth asked him.

And I'm puzzled too by Farfrae's focus on Susan — can't reason why other than to wonder, after meeting her, about Henchard's actions both in 'selling' her and then reclaiming her.

I too feel that there are going to me more secrets and trouble.

Thank you Peter and Claudia for your thoughts on the illustration, and how it is framed. I loved the thought of a picture within a picture. And I had not thought to connect it all to the thin wall at the King of Prussia, which was concealing a door. It seems Elizabeth is always looking at Farfrae from a window, or a door. You are right that we should be paying attention to this!

And how about the blowing of the husks of wheat by Farfrae! I agree with Jean Farfrae’s action of blowing the wheat husks from Elizabeth-Jane’s dress is both intimate, and able to be interpreted as subtly sexual. This is a very clever bit of writing by Hardy. Farfrae is blowing her back and side hair, her neck, her bonnet her victorine. That all struck me as very intimate. It was interesting that Elizabeth neither assents or dissents, and Farfrae takes charge. Elizabeth is an observer, not an action taker and she remains quite passive at this moment.

Kathleen, I'm glad you pointed out that Henchard backs down completely when Elizabeth asks him about changing her name. He's all bluster with Susan, but when it comes to Elizabeth he acts sheepish. Is this his lingering shame and guilt for abandoning his daughter? I remember in Chapter XII the narrator gives us three resolves that Henchard made for himself regarding marrying Susan. 1) To make amend to Susan 2) to provide for Elizabeth and 3) to castigate himself with thorns by marrying below his standing. That last one is curious, and I think indicates a lot of shame and guilt that Henchard carries on his shoulders.

And how about the blowing of the husks of wheat by Farfrae! I agree with Jean Farfrae’s action of blowing the wheat husks from Elizabeth-Jane’s dress is both intimate, and able to be interpreted as subtly sexual. This is a very clever bit of writing by Hardy. Farfrae is blowing her back and side hair, her neck, her bonnet her victorine. That all struck me as very intimate. It was interesting that Elizabeth neither assents or dissents, and Farfrae takes charge. Elizabeth is an observer, not an action taker and she remains quite passive at this moment.

Kathleen, I'm glad you pointed out that Henchard backs down completely when Elizabeth asks him about changing her name. He's all bluster with Susan, but when it comes to Elizabeth he acts sheepish. Is this his lingering shame and guilt for abandoning his daughter? I remember in Chapter XII the narrator gives us three resolves that Henchard made for himself regarding marrying Susan. 1) To make amend to Susan 2) to provide for Elizabeth and 3) to castigate himself with thorns by marrying below his standing. That last one is curious, and I think indicates a lot of shame and guilt that Henchard carries on his shoulders.

One last thought, I coudn't help but wonder at this observation by Elizabeth

"when walking together Henchard would lay his arm familiaryly on his manager's shoulder, as if Farfrae were a younger brother, bearing so heavily that his slight figure bent under the weight"

First that's a very keen observation by Elizabeth and tells us a lot about her intelligence. But it also indicates a very lopsided relationship between Farfrae and Henchard. Is that a bit of foreshadowing too??

"when walking together Henchard would lay his arm familiaryly on his manager's shoulder, as if Farfrae were a younger brother, bearing so heavily that his slight figure bent under the weight"

First that's a very keen observation by Elizabeth and tells us a lot about her intelligence. But it also indicates a very lopsided relationship between Farfrae and Henchard. Is that a bit of foreshadowing too??

Thank you so much everyone, for your marvellous comments over the last couple of days, and especially my co-mod Bridget for taking the reins at virtually no notice! 😊I've thoroughly enjoyed reading all these new insights, often with completely new realisation about Hardy's subtlety.

Let's move on ...

Let's move on ...

Chapter 15

Elizabeth-Jane, although she now attracts Donald Farfrae’s gaze, is still not noticed by the townspeople until her dress becomes more stylish. Henchard had bought a fine pair of gloves for her, and she bought a bonnet to match them. Then she found she had no dress to match that, and so her wardrobe grows. Some people in Casterbridge feel she has artfully created an effect by dressing plainly for so long in order to make her new appearance the more noticeable by contrast.

Elizabeth-Jane feels surprised and overwhelmed by the admiration and notice of the town, despite reminding herself that she may have gained the admiration of those types whose admiration is not worth having. But Farfrae, too, admires her. However, Elizabeth-Jane feels, after consideration, that she is admired for her appearance, which is not supported by an educated mind or a truly genteel background. She feels it would be better to sell her fine things and purchase grammar books and histories instead.

Henchard and Farfrae continue their close friendship, and yet there are hints of a disagreement. At six o’clock one evening, as the workers are leaving, Henchard calls back to a slack-jawed young man named Abel Whittle warning him not to be late again. Abel often over-sleeps and his workmates forget to wake him up. During the previous week, he had kept other workers waiting for almost an hour on two different days. Henchard will not listen to his pleas, but says he will thrash him if he is not there promptly the next morning.

The next morning at six, Abel has still not arrived at work. At six-thirty Henchard finds that the man who was to work with him that day had been waiting with his wagon for twenty minutes. Abel arrives out-of-breath just at that moment, and Henchard yells at him, swearing that if he is late the next morning that he will personally drag Abel out of bed. Abel tries to explain his situation, but Henchard will not listen.

The next morning, the wagons have to travel all the way to Blackmoor Vale, so the other workers arrive at four, but there is no sign of Abel. Henchard rushes to his house and yells at the young man to head to the granary—never mind his breeches—or that he would be fired that day. Farfrae encounters the half-dressed Abel in the yard before Henchard returns. Unimpressed with the situation, Farfrae orders Abel to return home, dress himself, and come to work like a man. Henchard arrives and exclaims over Abel leaving, and all the men look towards Farfrae. Farfrae insists that his joke has been carried far enough, and when Henchard won’t budge, he says that either Abel goes home and gets his clothes, or he, Farfrae, will leave Henchard’s employment for good.

Farfrae and Henchard privately converse, and Farfrae entreats him not to behave in this tyrannical way. Henchard is hurt that Farfrae would speak to him as he did in front of all the workers, and says it must be because he had told him his secret, but Farfrae says he had forgotten it. Henchard is moody all day, and when asked a question by a worker, exclaims bitterly: “Ask Mr. Farfrae. He’s master here!”

Thus Henchard, who was once the most admired man among his workers and in Casterbridge, is the most admired no longer. A farmer in Durnover sends for Mr. Farfrae to value a haystack, but the child delivering the message meets Henchard instead. At Henchard’s questioning, the child says that everyone always sends for Mr. Farfrae because they all like him so much. The child repeats the gossip in the town to Henchard: Farfrae is said to be better tempered then him, as well as cleverer, and that some of the women go so far as to say that they wish Farfrae were in charge rather than Henchard.

Henchard goes to value the hay in Durnover and meets Farfrae along the route. Farfrae accompanies him, singing as he walks, but he stops as they arrive remembering that the father in the family has recently died. Henchard sneers at Farfrae’s interest in protecting others’ feelings, including his own. Farfrae apologises if he has hurt Henchard in any way. Henchard decides to let Farfrae value the hay, and the pair part with their friendship renewed. However, Henchard often regrets having confessed the full secrets of his past to Farfrae, whom he now thinks of with a vague dread.

Elizabeth-Jane, although she now attracts Donald Farfrae’s gaze, is still not noticed by the townspeople until her dress becomes more stylish. Henchard had bought a fine pair of gloves for her, and she bought a bonnet to match them. Then she found she had no dress to match that, and so her wardrobe grows. Some people in Casterbridge feel she has artfully created an effect by dressing plainly for so long in order to make her new appearance the more noticeable by contrast.

Elizabeth-Jane feels surprised and overwhelmed by the admiration and notice of the town, despite reminding herself that she may have gained the admiration of those types whose admiration is not worth having. But Farfrae, too, admires her. However, Elizabeth-Jane feels, after consideration, that she is admired for her appearance, which is not supported by an educated mind or a truly genteel background. She feels it would be better to sell her fine things and purchase grammar books and histories instead.

Henchard and Farfrae continue their close friendship, and yet there are hints of a disagreement. At six o’clock one evening, as the workers are leaving, Henchard calls back to a slack-jawed young man named Abel Whittle warning him not to be late again. Abel often over-sleeps and his workmates forget to wake him up. During the previous week, he had kept other workers waiting for almost an hour on two different days. Henchard will not listen to his pleas, but says he will thrash him if he is not there promptly the next morning.

The next morning at six, Abel has still not arrived at work. At six-thirty Henchard finds that the man who was to work with him that day had been waiting with his wagon for twenty minutes. Abel arrives out-of-breath just at that moment, and Henchard yells at him, swearing that if he is late the next morning that he will personally drag Abel out of bed. Abel tries to explain his situation, but Henchard will not listen.

The next morning, the wagons have to travel all the way to Blackmoor Vale, so the other workers arrive at four, but there is no sign of Abel. Henchard rushes to his house and yells at the young man to head to the granary—never mind his breeches—or that he would be fired that day. Farfrae encounters the half-dressed Abel in the yard before Henchard returns. Unimpressed with the situation, Farfrae orders Abel to return home, dress himself, and come to work like a man. Henchard arrives and exclaims over Abel leaving, and all the men look towards Farfrae. Farfrae insists that his joke has been carried far enough, and when Henchard won’t budge, he says that either Abel goes home and gets his clothes, or he, Farfrae, will leave Henchard’s employment for good.

Farfrae and Henchard privately converse, and Farfrae entreats him not to behave in this tyrannical way. Henchard is hurt that Farfrae would speak to him as he did in front of all the workers, and says it must be because he had told him his secret, but Farfrae says he had forgotten it. Henchard is moody all day, and when asked a question by a worker, exclaims bitterly: “Ask Mr. Farfrae. He’s master here!”

Thus Henchard, who was once the most admired man among his workers and in Casterbridge, is the most admired no longer. A farmer in Durnover sends for Mr. Farfrae to value a haystack, but the child delivering the message meets Henchard instead. At Henchard’s questioning, the child says that everyone always sends for Mr. Farfrae because they all like him so much. The child repeats the gossip in the town to Henchard: Farfrae is said to be better tempered then him, as well as cleverer, and that some of the women go so far as to say that they wish Farfrae were in charge rather than Henchard.

Henchard goes to value the hay in Durnover and meets Farfrae along the route. Farfrae accompanies him, singing as he walks, but he stops as they arrive remembering that the father in the family has recently died. Henchard sneers at Farfrae’s interest in protecting others’ feelings, including his own. Farfrae apologises if he has hurt Henchard in any way. Henchard decides to let Farfrae value the hay, and the pair part with their friendship renewed. However, Henchard often regrets having confessed the full secrets of his past to Farfrae, whom he now thinks of with a vague dread.

A little more …

About the Locations in chapters 13 and 14

Susan and Elizabeth-Jane now live in a cottage “in the upper or western part of the town, near the Roman wall, and the avenue which overshadowed it.” (chapter 13)

A small portion of Roman stonework which formed part of the west wall still remains between Top o’ Town and Princes Street.

“Widow Newson” (Susan) and Michael Henchard remarry at the church after a respectable interval. The parish church for the west end of town was Holy Trinity Church, a medieval church which was rebuilt in 1824, and then again in 1875. (chapter 13)

“The corn grown on the upland side of the borough was garnered by farmers who lived in an eastern purlieu called Durnover. Here wheat-ricks overhung the old Roman street, and thrust their eaves against the church tower;” (chapter 14)

Durnover and Durnover Moor are mentioned a few times from now on. “Durnover” is a reference to Fordington, an historic area of Dorchester, Hardy knew this area well, and it partly inspired this novel, as well as a few poems. In real life, St. George’s Church, Fordington, ("Durnover") was considerably lengthened in phases between 1909 and 1928, thus destroying the Georgian chancel of 1750. The tower survived, but not the adjoining farmyard.

About the Locations in chapters 13 and 14

Susan and Elizabeth-Jane now live in a cottage “in the upper or western part of the town, near the Roman wall, and the avenue which overshadowed it.” (chapter 13)

A small portion of Roman stonework which formed part of the west wall still remains between Top o’ Town and Princes Street.

“Widow Newson” (Susan) and Michael Henchard remarry at the church after a respectable interval. The parish church for the west end of town was Holy Trinity Church, a medieval church which was rebuilt in 1824, and then again in 1875. (chapter 13)

“The corn grown on the upland side of the borough was garnered by farmers who lived in an eastern purlieu called Durnover. Here wheat-ricks overhung the old Roman street, and thrust their eaves against the church tower;” (chapter 14)

Durnover and Durnover Moor are mentioned a few times from now on. “Durnover” is a reference to Fordington, an historic area of Dorchester, Hardy knew this area well, and it partly inspired this novel, as well as a few poems. In real life, St. George’s Church, Fordington, ("Durnover") was considerably lengthened in phases between 1909 and 1928, thus destroying the Georgian chancel of 1750. The tower survived, but not the adjoining farmyard.

The “sixpence for a fairing” which Henchard uses to bribe the little boy into telling him the villagers’ opinion of him means a silver sixpence for a little cake or gift from a fair.

I find this chapter interesting in structure. It starts with Elizabeth-Jane’s maturing and acceptance in the town, has a pivotal interlude in the centre, and then finishes by again examining character; this time the relationship between Farfrae and Henchard. The episode with Abel Whittle is pure Hardy: amusing but poignant too.

Elizabeth-Jane draws the attention of the villagers as she improves her fashionable appearance, as the villagers suppose her new dress to be a deliberate contrast to her old style. We see then that even at this time, fashion was the focus of interest, attention, and gossip. Some villagers misunderstand Elizabeth-Jane’s innocence and purity.

Elizabeth-Jane takes a logical view of her new popularity, realising that it is based on her appearance, and not based on her true worth: her character and her mind. She feels that those qualities are more important, which demonstrates her level-headedness, as well as her confidence that, as a woman, she is worth more than her appearance. She is, however, pleased by Farfrae’s attention.

I find this chapter interesting in structure. It starts with Elizabeth-Jane’s maturing and acceptance in the town, has a pivotal interlude in the centre, and then finishes by again examining character; this time the relationship between Farfrae and Henchard. The episode with Abel Whittle is pure Hardy: amusing but poignant too.

Elizabeth-Jane draws the attention of the villagers as she improves her fashionable appearance, as the villagers suppose her new dress to be a deliberate contrast to her old style. We see then that even at this time, fashion was the focus of interest, attention, and gossip. Some villagers misunderstand Elizabeth-Jane’s innocence and purity.

Elizabeth-Jane takes a logical view of her new popularity, realising that it is based on her appearance, and not based on her true worth: her character and her mind. She feels that those qualities are more important, which demonstrates her level-headedness, as well as her confidence that, as a woman, she is worth more than her appearance. She is, however, pleased by Farfrae’s attention.

"And yet the seed that was to lift the foundation of this friendship was at that moment taking root in a chink of its structure."

This seems a portentous way of describing the source of Henchard and Farfrae’s falling out: a seeming trivial incident involving Abel Whittle, the perpetually tardy worker. We see that the conflict between Henchard and Farfrae arises from a different management style. Henchard scolds Abel for his tardiness, because he cares most about people following his orders. The shortness of temper we have seen before is emphasised in his interactions with Abel, as the young man tries his patience. Henchard is interested only in Abel’s performance and not his explanation of his tardiness. To us though, this might seem tyrannical.

Henchard’s treatment of Abel goes against propriety, as well as the worker’s dignity. He does not let the young man get dressed, which shames him in front of the other workers. Farfrae stands up for Abel, saying that he will leave if Abel is not treated with decency and respect, and sent home to retrieve his clothes. Farfrae uses his own weight, which is his importance to the business, to force the issue and get his own way. His way is, however, the kind and respectful treatment of any worker. Farfrae is more generous.

He believes Henchard’s behaviour is tyrannical, but Henchard does not consider the ways he could improve. Instead, he sees only a threat to his own reputation: that Farfrae challenged him, publicly, and undermined his authority as the master.

Henchard learns from a child that Farfrae is more popular than he is among the villagers. Shouldn’t this have been obvious to Henchard already, when there have been so many examples of Farfrae’s popularity? He seems to have been blinded to it by his regard for Farfrae. However, as soon as Farfrae challenges him, Henchard begins to feel threatened and to see Farfrae’s popularity as a further threat.

Henchard and Farfrae’s friendship is restored because of Farfrae’s immediate and honest apology when Henchard acts as if he has been offended. Henchard is able, at this point, to accept the apology, but he is worried, and fears Farfrae has power over him because of his knowledge of Henchard’s secret.

We seem to have another looming threat here, to add to all the secrets. I loved the nuances in this chapter, describing the psychology of personalities so well, especially Elizabeth-Jane, Henchard and Farfrae.

This seems a portentous way of describing the source of Henchard and Farfrae’s falling out: a seeming trivial incident involving Abel Whittle, the perpetually tardy worker. We see that the conflict between Henchard and Farfrae arises from a different management style. Henchard scolds Abel for his tardiness, because he cares most about people following his orders. The shortness of temper we have seen before is emphasised in his interactions with Abel, as the young man tries his patience. Henchard is interested only in Abel’s performance and not his explanation of his tardiness. To us though, this might seem tyrannical.

Henchard’s treatment of Abel goes against propriety, as well as the worker’s dignity. He does not let the young man get dressed, which shames him in front of the other workers. Farfrae stands up for Abel, saying that he will leave if Abel is not treated with decency and respect, and sent home to retrieve his clothes. Farfrae uses his own weight, which is his importance to the business, to force the issue and get his own way. His way is, however, the kind and respectful treatment of any worker. Farfrae is more generous.

He believes Henchard’s behaviour is tyrannical, but Henchard does not consider the ways he could improve. Instead, he sees only a threat to his own reputation: that Farfrae challenged him, publicly, and undermined his authority as the master.

Henchard learns from a child that Farfrae is more popular than he is among the villagers. Shouldn’t this have been obvious to Henchard already, when there have been so many examples of Farfrae’s popularity? He seems to have been blinded to it by his regard for Farfrae. However, as soon as Farfrae challenges him, Henchard begins to feel threatened and to see Farfrae’s popularity as a further threat.

Henchard and Farfrae’s friendship is restored because of Farfrae’s immediate and honest apology when Henchard acts as if he has been offended. Henchard is able, at this point, to accept the apology, but he is worried, and fears Farfrae has power over him because of his knowledge of Henchard’s secret.

We seem to have another looming threat here, to add to all the secrets. I loved the nuances in this chapter, describing the psychology of personalities so well, especially Elizabeth-Jane, Henchard and Farfrae.

Tomorrow will be a free day. We will read chapter 16 on Wednesday 9th July

Thanks all for making this such a great reading experience, despite a couple of recent blips. I'm looking forward to yet more insights 🙂

Thanks all for making this such a great reading experience, despite a couple of recent blips. I'm looking forward to yet more insights 🙂

How nice to see you again, Jean! I am seconding Kathleen's cheers for Bridget's moderation on short notice!

How nice to see you again, Jean! I am seconding Kathleen's cheers for Bridget's moderation on short notice!You said it all!

The preceding chapter already hinted at the particular alchemy of Henchard's relationship with Farfrae:

"Her [Elizabeth-Jane's] quiet eye discerned that Henchard’s tigerish affection for the younger man, his constant liking to have Farfrae near him, now and then resulted in a tendency to domineer, which, however, was checked in a moment when Donald exhibited marks of real offence." (Chapter 14)

Henchard had some animal instinct. The tiger comparison suggests an innate visceral wildness, no real calculation, a need to dominate and swallow a prey.

Henchard acts instantly and instinctively, without taking consequences into account. He doesn't mind if he is offending someone - Abel Whittle is a great and unfortunate example. The only barrier that now stops Henchard is the fact that he unwisely revealed his secrets to Farfrae.

As you mentioned, Farfrae is a threat to him because of his managerial qualities, perhaps his sharpness, his sense of organisation, his growing popularity in the town, but also because of Elizabeth-Jane's attention. A budding romance ahead?

In short, should anything wrong occur between the two men, Farfrae might be a ticking bomb if he were less discreet than we think him to be, or if he was mistreated by Henchard just as we have just seen Abel Whittle mistreated, or Susan eighteen years before, or the Jersey belle who was dismissed by mail.

Welcome back Jean, and may I also add my tip of the hat to Bridget.

Welcome back Jean, and may I also add my tip of the hat to Bridget. I agree with the idea that there are many ways to identify and find a person’s true worth, and this chapter demonstrates that Elizabeth-Jane is a remarkable young lady. Her desire to improve her wardrobe is understandable given her past struggles with her mother. Elizabeth-Jane does, however, reveal the depth of her character when she self-examines herself and wants to improve her inner self, her mind and character in addition to her external self as exhibited by her clothes.

And speaking of clothes, I found the interactions between Farfrae, Henchard and the farm hand Able to be equally revealing of their characters. Henchard sees nothing wrong in punishing and humiliating Able by making him go to work without his pants. Farfrae objects. To him a man’s worth should not be exhibited in a public humiliation. Interesting opposites in this chapter. Hardy introduces how the measure of a human is often made primarily on the external characteristics that are easily seen in display at the expense of a person taking the true measure of a person by discovering the internal nature and value of a person.

I need to pay closer attention to how Hardy portrays his characters through the clothes they wear. In retrospect, the scene where a well-dressed Henchard consciously put on a coat to hid his expensive clothing comes to mind as a marker of the two-sided nature of his character.

Welcome back, Jean, and thank you for your enticing analysis! I'm so glad you mentioned the structure, which I think impacted me subconsciously. I love the contrast between Henchard and Elizabeth-Jane when it comes to external image and status. He had no inkling he was doing anything wrong and had to be publicly reproached by Farfrae, whereas she was able on her own to temper her enjoyment of her new status with understanding of qualities she was lacking. We're liking E-J, aren't we?!

Welcome back, Jean, and thank you for your enticing analysis! I'm so glad you mentioned the structure, which I think impacted me subconsciously. I love the contrast between Henchard and Elizabeth-Jane when it comes to external image and status. He had no inkling he was doing anything wrong and had to be publicly reproached by Farfrae, whereas she was able on her own to temper her enjoyment of her new status with understanding of qualities she was lacking. We're liking E-J, aren't we?!It made me laugh to think about Abel's public humiliation, when nowadays people go out shopping, to university classes, and for all I know to some workplaces literally in their pajamas! :-)

Kathleen wrote: "Welcome back, Jean, and thank you for your enticing analysis! I'm so glad you mentioned the structure, which I think impacted me subconsciously. I love the contrast between Henchard and Elizabeth-J..."

Kathleen wrote: "Welcome back, Jean, and thank you for your enticing analysis! I'm so glad you mentioned the structure, which I think impacted me subconsciously. I love the contrast between Henchard and Elizabeth-J..."Kathleen, you're comments about pajamas made me giggle because I see this far too often. Yes, pajama pants are comfortable — but a little too comfortable and I don't like it. I also dislike the wearing of Ugg boots because it's Southern California and it is never cold enough for Ugg boots, especially when worn with shorts!

I did laugh about poor Abel but I also felt very sorry for him. Let's face it, yes, he does need to learn about keeping time (heck even a little early) but to shame him before the entire village is going a bit too far and make Henchard look spiteful. Henchard has to learn empathy but I don't think he will.

And now, he's mad at Farfrae. If he ends up splitting with Farfrae (and it seems likely), it will be like cutting your own nose off to spite your face.

I also didn't like the chastisement given to Abel by Henchard. As Pamela said, Abel did need to learn some time management and responsibility to his job, but ridiculing him wasn't necessary. It shows Henchard in a cruel light.

I also didn't like the chastisement given to Abel by Henchard. As Pamela said, Abel did need to learn some time management and responsibility to his job, but ridiculing him wasn't necessary. It shows Henchard in a cruel light. Henchard seems to be causing his own problems. He ridicules Abel and looks bad to the rest of the workers, he tells Farfrae a secret then is upset with him for knowing the secret, he hires Farfrae for his knowledge then is upset that the townspeople admire that knowledge. He seems to look for the bad side of any situation.

Kathleen, yes, Elizabeth-Jane is proving to be a solid, dependable person. I like her, too.

Petra wrote: Henchard seems to be causing his own problems. He ridicules Abel and looks bad to the rest of the workers, he tells Farfrae a secret then is upset with him for knowing the secret, he hires Farfrae for his knowledge then is upset that the townspeople admire that knowledge. He seems to look for the bad side of any situation.

Petra wrote: Henchard seems to be causing his own problems. He ridicules Abel and looks bad to the rest of the workers, he tells Farfrae a secret then is upset with him for knowing the secret, he hires Farfrae for his knowledge then is upset that the townspeople admire that knowledge. He seems to look for the bad side of any situation.Exactly, Petra!

Henchard seems to be his own enemy in acting too quickly without considering the whole situation before.

Peter wrote: "I need to pay closer attention to how Hardy portrays his characters through the clothes they wear."

I was thinking about this too, Peter. Elizabeth's fashion make-over starts with Henchard giving her a pair of gloves. And my first thought was, is Henchard "throwing down a gauntlet" to Elizabeth? He could have bought her a bonnet, or some ribbon, but no he gave her gloves - the traditional gauntlet of a knight issuing a challenge. I'm probably over analyzing this, but it made me wonder.

I was thinking about this too, Peter. Elizabeth's fashion make-over starts with Henchard giving her a pair of gloves. And my first thought was, is Henchard "throwing down a gauntlet" to Elizabeth? He could have bought her a bonnet, or some ribbon, but no he gave her gloves - the traditional gauntlet of a knight issuing a challenge. I'm probably over analyzing this, but it made me wonder.

A man could give a woman a gift of gloves, but not a bonnet unless they were engaged to be married. A bonnet would be appropriate gift from a father or a family member, but Henchard is not considered to be Elizabeth-Jane's father at this point by society. It's questionable whether a step-father would be considered to be a family member, so Henchard is picking a socially correct gift in the 1800s.

A man could give a woman a gift of gloves, but not a bonnet unless they were engaged to be married. A bonnet would be appropriate gift from a father or a family member, but Henchard is not considered to be Elizabeth-Jane's father at this point by society. It's questionable whether a step-father would be considered to be a family member, so Henchard is picking a socially correct gift in the 1800s.

Thanks for that Connie. That's great info to have. The Victorians had lots of rules, didn't they? There were all kinds of rules about flowers and their meanings. I didn't know this part about articles of clothing.

I also wanted to post about Able Whittle. When I read Claire Tomalin's book Thomas Hardy I learned that Able Whittle was a real man. Well, the name came from a real person, but he was a farmer, not a pauper who couldn't wake up on time.

The story goes that Able Whittle was a prosperous farmer from Maiden Newton, where Jemima Hardy worked at a vicarage as a girl. His name appears in the census there in 1851 and 1861. He owned 1,000 acres and lived on Church Street, near the vicarage, with his wife and three children, plus servants. Here's a little of what Tomalin wrote:

"Jemima would have known about him from her friends and could well have known him herself. She may have given Hardy the name, and she may have had reasons of her own for suggesting it to Hardy, or he may simply have found it himself and liked the sound of it. Even the faintest hint that he talked about his work with his mother is intriguing, since he is silent on the subject"

I just thought you all might like to have that little bit of information. As we've seen Hardy played around with the names of the characters in this novel quite a bit. Able Whittle was "Smallbone, Small, Wringbone and John Whittle" before finally settling on Able Whittle. I like that name. It has a nice ring to it. But it's also a nice ironic touch that the man who is "unable" to wake up, is named Able. :-)

The story goes that Able Whittle was a prosperous farmer from Maiden Newton, where Jemima Hardy worked at a vicarage as a girl. His name appears in the census there in 1851 and 1861. He owned 1,000 acres and lived on Church Street, near the vicarage, with his wife and three children, plus servants. Here's a little of what Tomalin wrote:

"Jemima would have known about him from her friends and could well have known him herself. She may have given Hardy the name, and she may have had reasons of her own for suggesting it to Hardy, or he may simply have found it himself and liked the sound of it. Even the faintest hint that he talked about his work with his mother is intriguing, since he is silent on the subject"

I just thought you all might like to have that little bit of information. As we've seen Hardy played around with the names of the characters in this novel quite a bit. Able Whittle was "Smallbone, Small, Wringbone and John Whittle" before finally settling on Able Whittle. I like that name. It has a nice ring to it. But it's also a nice ironic touch that the man who is "unable" to wake up, is named Able. :-)

Bridget wrote: "I also wanted to post about Able Whittle. When I read Claire Tomalin's book Thomas Hardy I learned that Able Whittle was a real man. Well, the name came from a real pe..."

Bridget wrote: "I also wanted to post about Able Whittle. When I read Claire Tomalin's book Thomas Hardy I learned that Able Whittle was a real man. Well, the name came from a real pe..."Bridget

Thank you. I love to learn as much of the bits and details of an author and their novels as possible.

And, of course, putting a deeper/humous touch a person’s name gives the text much more breadth and depth.

Bridget wrote: "I also wanted to post about Able Whittle. When I read Claire Tomalin's book Thomas Hardy I learned that Able Whittle was a real man. Well, the name came from a real pe..."

Bridget wrote: "I also wanted to post about Able Whittle. When I read Claire Tomalin's book Thomas Hardy I learned that Able Whittle was a real man. Well, the name came from a real pe..."That's great background, Bridget. I had wondered if Hardy was thinking of the Cain and Able Biblical story where Able is slayed by Cain (Michael Henchard). So it's good to know the real story behind the name.

Bridget, thanks for the background story on Abel Whittle's name. I find it interesting when an author puts part of his real-life Life into the story. Hardy may or may not have known the original Abel Whittle, but he most definitely heard about him in some way and the name stuck with him, for either good or bad reasons. This inclusion of "real life" brings the story closer to the reader, in some way. There's a bridge between Hardy and us, so to speak.

Bridget, thanks for the background story on Abel Whittle's name. I find it interesting when an author puts part of his real-life Life into the story. Hardy may or may not have known the original Abel Whittle, but he most definitely heard about him in some way and the name stuck with him, for either good or bad reasons. This inclusion of "real life" brings the story closer to the reader, in some way. There's a bridge between Hardy and us, so to speak.

Thank you Bridget for the additional information about the real Abel Whittle.

Thank you Bridget for the additional information about the real Abel Whittle. The novel character has a funny name. I also see him as someone, a simple fellow (this is evidenced by his somewhat naive way of speaking), being "bullied" by Henchard in front of everyone else, just as Susan was when she was "bullied" and finally sold by the same Henchard eighteen years or so ago at the fair in the furmity tent.

This chapter shows how much Henchard's balance is precarious, even if he does not drink.

Chapter 16

Henchard grows more reserved toward Farfrae, no longer putting his arm around the young man, or inviting him to dinner. Otherwise, their business relationship continues in a similar vein until a day of celebration of a national holiday is proposed. Farfrae has the idea to create a tent for some small celebrations, and upon hearing his idea, Henchard feels that he has been remiss, as the mayor of the town, in not organising some public festivities himself.

Henchard begins preparing for his celebrations, and everyone in the town applauds when they hear that he plans to pay for it all himself. Farfrae, on the other hand, plans to charge a small price per head for admission to his tent; an idea that Henchard scoffs at, wondering who would pay for such a thing.

Henchard’s celebrations feature a number of physical activities and games. He has greasy poles set up for climbing, a space for boxing and wrestling, and a free tea for everyone. Henchard views Farfrae’s awkward tent construction and feels confident that his own preparations are more exciting and extravagant.

The appointed day arrives, but it is overcast and gray, and starts to rain at noon. Some people attend Henchard’s event, but the storm worsens, and the tent he had set up for the tea blows over. By six o’clock though, the storm is over and Henchard hopes his celebrations will still continue. The townspeople, however, do not arrive, and Henchard learns upon questioning one man that nearly everyone is at Farfrae’s celebration.

“But Henchard continued moody and silent, and when one of the men inquired of him if some oats should be hoisted to an upper floor or not, he said shortly, ‘Ask Mr. Farfrae. He’s master here!’ Morally he was; there could be no doubt of it. Henchard, who had hitherto been the most admired man in his circle, was the most admired no longer.”

Henchard moodily closes down his celebrations and returns home. At dusk, he walks outside and follows others to Farfrae’s tent. His ingeniously constructed pavilion creates a space both for a band, and for the dance taking place. Henchard observes that Farfrae’s dancing is much admired and that he has an endless selection of dance partners. He overhears the villagers discussing himself and Farfrae, saying that he must have been a fool to plan an outdoor event on that day. Farfrae is also praised for his management, which has greatly improved Henchard’s business.

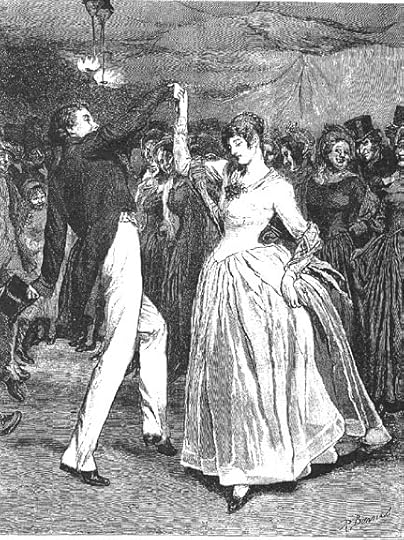

Back in the tent, Elizabeth-Jane is dancing with Farfrae.

“Farfrae was footing a quaint little dance with Elizabeth Jane” by Robert Barnes - 13th February 1886

After the dance, she looks to Henchard for fatherly approval, but instead he fixes an antagonistic glare on Farfrae. A few good-natured friends of Henchard’s tease him for having been bested by Farfrae in the creation of a town celebration. Henchard gloomily responds that Farfrae’s time as his manager is about to end, reinforcing his statement as Farfrae approaches and hears him.

“Mr. Farfrae’s time as my manager is drawing to a close--isn’t it, Farfrae?”

The young man, who could now read the lines and folds of Henchard’s strongly-traced face as if they were clear verbal inscriptions, quietly assented; and when people deplored the fact, and asked why it was, he simply replied that Mr. Henchard no longer required his help. Henchard went home, apparently satisfied. But in the morning, when his jealous temper had passed away, his heart sank within him at what he had said and done. He was the more disturbed when he found that this time Farfrae was determined to take him at his word.“

By the next morning, Henchard’s jealous temper has passed and he regrets his pronouncement that Farfrae would soon leave his employ. However, he finds that the young man is determined to do so after what Henchard said the previous evening.

Henchard grows more reserved toward Farfrae, no longer putting his arm around the young man, or inviting him to dinner. Otherwise, their business relationship continues in a similar vein until a day of celebration of a national holiday is proposed. Farfrae has the idea to create a tent for some small celebrations, and upon hearing his idea, Henchard feels that he has been remiss, as the mayor of the town, in not organising some public festivities himself.

Henchard begins preparing for his celebrations, and everyone in the town applauds when they hear that he plans to pay for it all himself. Farfrae, on the other hand, plans to charge a small price per head for admission to his tent; an idea that Henchard scoffs at, wondering who would pay for such a thing.

Henchard’s celebrations feature a number of physical activities and games. He has greasy poles set up for climbing, a space for boxing and wrestling, and a free tea for everyone. Henchard views Farfrae’s awkward tent construction and feels confident that his own preparations are more exciting and extravagant.

The appointed day arrives, but it is overcast and gray, and starts to rain at noon. Some people attend Henchard’s event, but the storm worsens, and the tent he had set up for the tea blows over. By six o’clock though, the storm is over and Henchard hopes his celebrations will still continue. The townspeople, however, do not arrive, and Henchard learns upon questioning one man that nearly everyone is at Farfrae’s celebration.

“But Henchard continued moody and silent, and when one of the men inquired of him if some oats should be hoisted to an upper floor or not, he said shortly, ‘Ask Mr. Farfrae. He’s master here!’ Morally he was; there could be no doubt of it. Henchard, who had hitherto been the most admired man in his circle, was the most admired no longer.”

Henchard moodily closes down his celebrations and returns home. At dusk, he walks outside and follows others to Farfrae’s tent. His ingeniously constructed pavilion creates a space both for a band, and for the dance taking place. Henchard observes that Farfrae’s dancing is much admired and that he has an endless selection of dance partners. He overhears the villagers discussing himself and Farfrae, saying that he must have been a fool to plan an outdoor event on that day. Farfrae is also praised for his management, which has greatly improved Henchard’s business.

Back in the tent, Elizabeth-Jane is dancing with Farfrae.

“Farfrae was footing a quaint little dance with Elizabeth Jane” by Robert Barnes - 13th February 1886

After the dance, she looks to Henchard for fatherly approval, but instead he fixes an antagonistic glare on Farfrae. A few good-natured friends of Henchard’s tease him for having been bested by Farfrae in the creation of a town celebration. Henchard gloomily responds that Farfrae’s time as his manager is about to end, reinforcing his statement as Farfrae approaches and hears him.

“Mr. Farfrae’s time as my manager is drawing to a close--isn’t it, Farfrae?”

The young man, who could now read the lines and folds of Henchard’s strongly-traced face as if they were clear verbal inscriptions, quietly assented; and when people deplored the fact, and asked why it was, he simply replied that Mr. Henchard no longer required his help. Henchard went home, apparently satisfied. But in the morning, when his jealous temper had passed away, his heart sank within him at what he had said and done. He was the more disturbed when he found that this time Farfrae was determined to take him at his word.“

By the next morning, Henchard’s jealous temper has passed and he regrets his pronouncement that Farfrae would soon leave his employ. However, he finds that the young man is determined to do so after what Henchard said the previous evening.

And a little more …

“a day of public rejoicing was suggested to the country at large in celebration of a national event that had recently taken place”

This might have been the birth of Princess Alice (1843) or possibly Prince Alfred (1844).

The tune which Elizabeth-Jane could not resist dancing to with Farfrae “being a tune of a busy, vaulting, leaping sort—some low notes on the silver string of each fiddle, then a skipping on the small, like running up and down ladders—“Miss M’Leod of Ayr”

was one of Thomas Hardy’s favourite dance tunes.

“I’ll go to Port-Bredy Great Market to-morrow myself. You can stay and put things right in your clothes-box, and recover strength to your knees after your vagaries.” [Henchard] planted on Donald an antagonistic glare that had begun as a smile”

Port-Bredy is actually Bridport (and my closest town!) It still has a lovely traditional English market with stalls every Saturday. Which leads me to more real-life locations … Are these interesting by the way, or too remote to be meaningful, really?

“a day of public rejoicing was suggested to the country at large in celebration of a national event that had recently taken place”

This might have been the birth of Princess Alice (1843) or possibly Prince Alfred (1844).

The tune which Elizabeth-Jane could not resist dancing to with Farfrae “being a tune of a busy, vaulting, leaping sort—some low notes on the silver string of each fiddle, then a skipping on the small, like running up and down ladders—“Miss M’Leod of Ayr”

was one of Thomas Hardy’s favourite dance tunes.

“I’ll go to Port-Bredy Great Market to-morrow myself. You can stay and put things right in your clothes-box, and recover strength to your knees after your vagaries.” [Henchard] planted on Donald an antagonistic glare that had begun as a smile”

Port-Bredy is actually Bridport (and my closest town!) It still has a lovely traditional English market with stalls every Saturday. Which leads me to more real-life locations … Are these interesting by the way, or too remote to be meaningful, really?

Locations

“Close to the town was an elevated green spot surrounded by an ancient square earthwork … whereon the Casterbridge people usually held any kind of merry-making, meeting, or sheep-fair that required more space than the streets would afford. On one side it sloped to the river Froom, and from any point a view was obtained of the country round for many miles. This pleasant upland was to be the scene of Henchard’s exploit.”

Henchard held his event at Poundbury, an Iron age hill fort lying just to the north west of Dorchester. Nowadays it is quite developed, with lots of housing. I've written more about Poundbury in the thread for the associated poem LINK HERE

**

Farfrae’s fete had “[an] unattractive exterior … in the West Walk, rick-cloths of different sizes and colours being hung up to the arching trees without any regard to appearance.”

This was in West Walk, one of a series of tree-lined walks which are still there, following the route of the old Roman walls.

“Close to the town was an elevated green spot surrounded by an ancient square earthwork … whereon the Casterbridge people usually held any kind of merry-making, meeting, or sheep-fair that required more space than the streets would afford. On one side it sloped to the river Froom, and from any point a view was obtained of the country round for many miles. This pleasant upland was to be the scene of Henchard’s exploit.”

Henchard held his event at Poundbury, an Iron age hill fort lying just to the north west of Dorchester. Nowadays it is quite developed, with lots of housing. I've written more about Poundbury in the thread for the associated poem LINK HERE

**

Farfrae’s fete had “[an] unattractive exterior … in the West Walk, rick-cloths of different sizes and colours being hung up to the arching trees without any regard to appearance.”

This was in West Walk, one of a series of tree-lined walks which are still there, following the route of the old Roman walls.

I loved all the discussion about Abel Whittle, and the history of the choice of name too, thank you Bridget! I also have a thought about the “Whittle” surname. Originally I expect it was used to describe the owner’s job, as so many ordinary names were. So “Whittle” might have been a woodcarver, as it means to form something from wood by slicing pieces off it.

But there is another meaning too. In English slang it means to complain or worry about something continually. “Stop whittling about it!” you might say. And I think that fits Abel Whittle as well!

But there is another meaning too. In English slang it means to complain or worry about something continually. “Stop whittling about it!” you might say. And I think that fits Abel Whittle as well!

Before the Abel Whittle incident, Henchard and Farfrae would probably have talked about the celebration together as friends. But now there is a reserve between them. Although they are able to maintain a professional relationship, their friendship is lost. The role of organising any public celebration would normally belong to the mayor, so Henchard creates a separate event, rather than help with Farfrae’s idea.