The History Book Club discussion

TECHNOLOGY/PRINT/MEDIA

>

NEWSPAPERS AND MAGAZINES

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jul 28, 2013 06:57AM)

(new)

Oct 03, 2010 06:28PM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

Timeline of the Newspaper Industry:

http://inventors.about.com/od/pstarti...

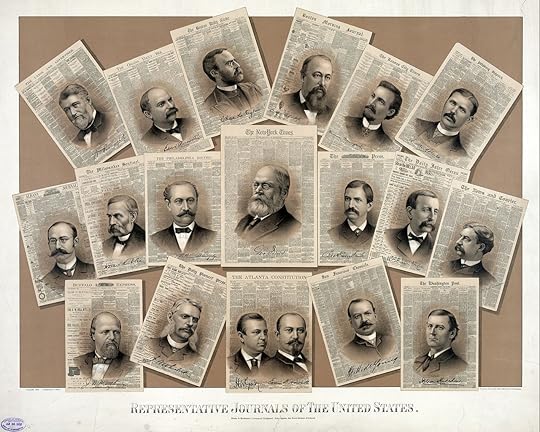

Representative Journals of the United States

"Representative journals of the United States. Copyright 1885. Compiled by A. J. Kane. T. Sinclair & Son, Lith., 506 & 508 North St., Philadelphia."

First row: The Union and Advertiser (William Purcell) - The Omaha Daily Bee (Edward Rosewater) - The Boston Daily Globe (Charles H. Taylor) - Boston Morning Journal (William Warland Clapp) - The Kansas City Times (Morrison Mumford) - The Pittsburgh Dispatch (Eugene M. O'Neill).

Second row: Albany Evening Journal (John A. Sleicher) - The Milwaukee Sentinel (Horace Rublee) - The Philadelphia Record (William M. Singerly) - The New York Times (George Jones) - The Philadelphia Press (Charles Emory Smith) - The Daily Inter Ocean (William Penn Nixon) - The News and Courier (Francis Warrington Dawson).

Third row: Buffalo Express (James Newson Matthews) - The Daily Pioneer Press (Joseph A. Wheelock) - The Atlanta Constitution (Henry Woodfin Grady & Evan Park Howell) - San Francisco Chronicle (Michael H. de Young) - The Washington Post (Stilson Hutchins). Date 1885

http://inventors.about.com/od/pstarti...

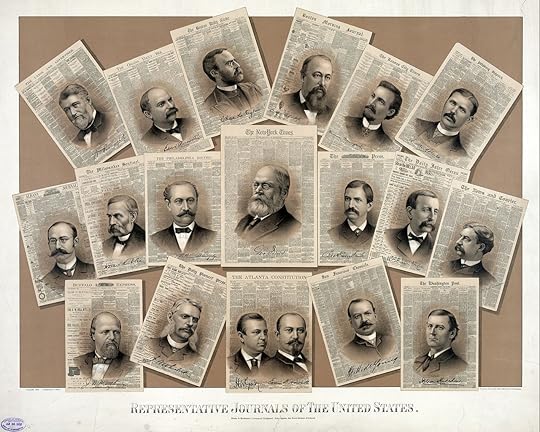

Representative Journals of the United States

"Representative journals of the United States. Copyright 1885. Compiled by A. J. Kane. T. Sinclair & Son, Lith., 506 & 508 North St., Philadelphia."

First row: The Union and Advertiser (William Purcell) - The Omaha Daily Bee (Edward Rosewater) - The Boston Daily Globe (Charles H. Taylor) - Boston Morning Journal (William Warland Clapp) - The Kansas City Times (Morrison Mumford) - The Pittsburgh Dispatch (Eugene M. O'Neill).

Second row: Albany Evening Journal (John A. Sleicher) - The Milwaukee Sentinel (Horace Rublee) - The Philadelphia Record (William M. Singerly) - The New York Times (George Jones) - The Philadelphia Press (Charles Emory Smith) - The Daily Inter Ocean (William Penn Nixon) - The News and Courier (Francis Warrington Dawson).

Third row: Buffalo Express (James Newson Matthews) - The Daily Pioneer Press (Joseph A. Wheelock) - The Atlanta Constitution (Henry Woodfin Grady & Evan Park Howell) - San Francisco Chronicle (Michael H. de Young) - The Washington Post (Stilson Hutchins). Date 1885

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (AKA Mark Twain) was part owner and editor of the Buffalo Express from 1869-1871.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (AKA Mark Twain) was part owner and editor of the Buffalo Express from 1869-1871. by Charles Neider (no photo)

by Charles Neider (no photo)

RIP, Ben Bradlee, famous editor of the Washington Post who broke the Watergate scandal. A giant in the newspaper world.

RIP, Ben Bradlee, famous editor of the Washington Post who broke the Watergate scandal. A giant in the newspaper world.

It isn't just the Giants, it's how they approached reporting that is the greater loss.

It isn't just the Giants, it's how they approached reporting that is the greater loss.When was the last time you heard a reporter say they were after "the truth?" Laughable as the notion of "the truth" is, reporters chasing that ghost produced much better reporting than is generally published/broadcast today.

Yes Martin you are right - it was not about sensationalism but about the facts and getting the right information out. I think that is why newspapers in part are not doing as well.

It is amazing how they allow their biases to cloud over and obscure the truth.

It is amazing how they allow their biases to cloud over and obscure the truth.

For my money, the most informative book I have read on media, and the one I most frequently consult, is Marshall Mcluhan's Understanding Media. Not only does this book originally published in the '60s anticipate the Internet, but it does so for all the right reasons.

For my money, the most informative book I have read on media, and the one I most frequently consult, is Marshall Mcluhan's Understanding Media. Not only does this book originally published in the '60s anticipate the Internet, but it does so for all the right reasons.UM is a history of media, from the alphabet's supplementation of oral communications to electronic technology's consumption of print.

The book is most famously known for the phrase "media is the message," but is the most profound delineation of media as extensions of the human anatomy and traces it through the development of print through the millennia, and electronic beginning with the telegraph.

The most significant difference, McLuhan points out, is control. With print, he who owns the printing press owns the message. But it's the guy generating the message, beginning with the telegraph, who owns the message.

The Internet, or digital network, where every fool sitting in front of a keyboard has a worldwide audience, is the ultimate extension of electronic media.

Newspapers are being wiped out because they failed to recognize the shift to a pull model where the value of their product is determined by demand from individuals pulling information off their site. No longer can a printing press owner expect to define the news by pushing it out, take it or leave it.

Watergate, I would argue, was the peak of the golden age of newspapering. It was shortly after - late '70s - that stories began to appear about small computers that people would have at home that would allow them to access information.

by

by

Marshall McLuhan

Marshall McLuhan

Times have changed and sometimes not for the better depending upon how you look at it.

Thanks for the add Martin and your perspective is always interesting. The book looks like a good one.

Thanks for the add Martin and your perspective is always interesting. The book looks like a good one.

He was the model for Citizen Kane. I have read this book and would recommend it....he had quite a checkered career.

He was the model for Citizen Kane. I have read this book and would recommend it....he had quite a checkered career.The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst

by David Nasaw (no photo)

by David Nasaw (no photo)Synopsis

Named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, Business Week, and GQ, THE CHIEF: THE LIFE OF WILLIAM RANDLOPH HEARST is “an absorbing and ingeniously organized biography . . . of the most powerful publisher America has ever known” (New York Times Book Review). Drawing on papers and interviews that were previously unavailable, as well as on newly released documentation of interactions with such figures as Hitler, Mussolini, Churchill, every president from Grover Cleveland to Franklin Roosevelt, and movie giants Louis B. Mayer, Jack Warner, and Irving Thalberg, David Nasaw completes the picture of this colossal American “engagingly, lucidly and fair-mindedly” (Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.).

“Outstandingly researched, elegantly but not flamboyantly written, and fair in its conclusions about Hearst’s astonishing career” (Wall Street Journal), THE CHIEF “must be regarded as the definitive study . . . It’s hard to imagine a more complete rendering of Hearst’s life” (Business Week).

Probably the most interesting time in newspaper "reporting".

Probably the most interesting time in newspaper "reporting".Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies

by W. Joseph Campbell (no photo)

by W. Joseph Campbell (no photo)Synopsis:

This offers a detailed and long-awaited reassessment of one of the most maligned periods in American journalism--the era of the yellow press. The study challenges and dismantles several prominent myths about the genre, finding that the yellow press did not foment--could not have fomented--the Spanish-American War in 1898, contrary to the arguments of many media historians. The study presents extensive evidence showing that the famous exchange of telegrams between the artist Frederic Remington and newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst--in which Hearst is said to have vowed to furnish the war with Spain--almost certainly never took place. The study also presents the results of a systematic content analysis of seven leading U. S. newspapers at 10 year intervals throughout the 20th century and finds that some distinguishing features of the yellow press live on in American journalism.

The yellow press period in American journalism history has produced many powerful and enduring myths-almost none of them true. This study explores these legends, presenting extensive evidence that:

The yellow press did not foment-could not have fomented-the Spanish-American War in 1898, contrary of the arguments of many media historians

The famous exchange of telegrams between the artist Frederic Remington and newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst-in which Hearst is said to have vowed to furnish the war with Spain-almost certainly never took place

The readership of the yellow press was not confined to immigrants and people having an uncertain command of English, as many media historians maintain

The study also presents the results of a detailed content analysis of seven leading U.S. newspapers at 10-year intervals, from 1899 to 1999. The content analysis--which included the "Denver Post, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Raleigh News and Observer, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, San Francisco Examine" and "Washington Post"--reveal that some elements characteristic of yellow journalism have been generally adopted by leading U. S. newspapers. This critical assessment encourages a more precise understanding of the history of yellow journalism, appealing to scholars of American journalism, journalism history, and practicing journalists."

Out of Print: Newspapers, Journalism and the Business of News in the Digital Age

by George Brock (no photo)

by George Brock (no photo)

Synopsis:

News and journalism are in the midst of upheaval. How does news publishing change when a newspaper sells as few as 300,000 copies but its website attracts 31 million visitors? The internet is not simply allowing faster, wider distribution of material: digital technology is demanding transformative change. Journalism needs to be rethought on a global scale and remade to meet the demands of new conditions.

Out of Print examines the past, present and future for a fragile industry battling a “perfect storm” of falling circulations, reduced advertising revenue, rising print costs and the impact of “citizen journalists” and free news aggregators. Author George Brock proposes an optimistic outlook on journalism's future, taking the view that it was always unstable and likely, always will be. He argues that journalism can flourish in a new communications age, and explains how current theory and practice have to change to fully exploit developing opportunities.

Incisive and authoritative, Out of Print analyzes the role and influence of journalism in the digital age and asks how it needs to adapt to survive

by George Brock (no photo)

by George Brock (no photo)Synopsis:

News and journalism are in the midst of upheaval. How does news publishing change when a newspaper sells as few as 300,000 copies but its website attracts 31 million visitors? The internet is not simply allowing faster, wider distribution of material: digital technology is demanding transformative change. Journalism needs to be rethought on a global scale and remade to meet the demands of new conditions.

Out of Print examines the past, present and future for a fragile industry battling a “perfect storm” of falling circulations, reduced advertising revenue, rising print costs and the impact of “citizen journalists” and free news aggregators. Author George Brock proposes an optimistic outlook on journalism's future, taking the view that it was always unstable and likely, always will be. He argues that journalism can flourish in a new communications age, and explains how current theory and practice have to change to fully exploit developing opportunities.

Incisive and authoritative, Out of Print analyzes the role and influence of journalism in the digital age and asks how it needs to adapt to survive

The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and Cultural Trans (Complete in One Volume)

by Elizabeth L. Eisenstein (no photo)

by Elizabeth L. Eisenstein (no photo)

Synopsis:

The first fully-documented historical analysis of the impact of the invention of printing upon European culture, and its importance as an agent of religious, political, social, scientific, and intellectual change.

Originally published in two volumes in 1980, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change is now issued in a paperback edition containing both volumes. The work is a full-scale historical treatment of the advent of printing and its importance as an agent of change. Professor Eisenstein begins by examining the general implications of the shift from script to print, and goes on to examine its part in three of the major movements of early modern times - the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the rise of modern science.

by Elizabeth L. Eisenstein (no photo)

by Elizabeth L. Eisenstein (no photo)Synopsis:

The first fully-documented historical analysis of the impact of the invention of printing upon European culture, and its importance as an agent of religious, political, social, scientific, and intellectual change.

Originally published in two volumes in 1980, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change is now issued in a paperback edition containing both volumes. The work is a full-scale historical treatment of the advent of printing and its importance as an agent of change. Professor Eisenstein begins by examining the general implications of the shift from script to print, and goes on to examine its part in three of the major movements of early modern times - the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the rise of modern science.

Preface to Plato

by

by

Eric Alfred Havelock

Eric Alfred Havelock

Synopsis:

Plato's frontal attack on poetry has always been a problem for sympathetic students, who have often minimized or avoided it. Beginning with the premise that the attack must be taken seriously, Eric Havelock shows that Plato's hostility is explained by the continued domination of the poetic tradition in contemporary Greek thought.

The reason for the dominance of this tradition was technological. In a nonliterate culture, stored experience necessary to cultural stability had to be preserved as poetry in order to be memorized. Plato attacks poets, particularly Homer, as the sole source of Greek moral and technical instruction--Mr. Havelock shows how the Iliad acted as an oral encyclopedia. Under the label of mimesis, Plato condemns the poetic process of emotional identification and the necessity of presenting content as a series of specific images in a continued narrative.

The second part of the book discusses the Platonic Forms as an aspect of an increasingly rational culture. Literate Greece demanded, instead of poetic discourse, a vocabulary and a sentence structure both abstract and explicit in which experience could be described normatively and analytically: in short a language of ethics and science

How does this book relate to the Future of Media?

According to Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin - "The Greeks matter because some of them, at least, recognized that they were passing through a change in how people frame the world. In their case, it was the change from the oral to the written, and this is of course the subject of one of the Platonic dialogues, Phaedrus. In it, Socrates declares himself fully aware that human capacities can change, and that as memory is displaced or funnelled into print, a variety of changes may set in which affect not only how we know things, but also who we are as human beings.

Eric Havelock’s Preface to Plato shows that the Greeks were aware that there was some connection, perhaps even an all-embracing connection, among forms of communication, memory and thought. It’s quite fascinating to me that people should have this awareness of a sea change in their way of knowing, this self-consciousness about it." -- Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin in interview with Five Books

More:

https://fivebooks.com/best-books/todd...

by

by

Eric Alfred Havelock

Eric Alfred HavelockSynopsis:

Plato's frontal attack on poetry has always been a problem for sympathetic students, who have often minimized or avoided it. Beginning with the premise that the attack must be taken seriously, Eric Havelock shows that Plato's hostility is explained by the continued domination of the poetic tradition in contemporary Greek thought.

The reason for the dominance of this tradition was technological. In a nonliterate culture, stored experience necessary to cultural stability had to be preserved as poetry in order to be memorized. Plato attacks poets, particularly Homer, as the sole source of Greek moral and technical instruction--Mr. Havelock shows how the Iliad acted as an oral encyclopedia. Under the label of mimesis, Plato condemns the poetic process of emotional identification and the necessity of presenting content as a series of specific images in a continued narrative.

The second part of the book discusses the Platonic Forms as an aspect of an increasingly rational culture. Literate Greece demanded, instead of poetic discourse, a vocabulary and a sentence structure both abstract and explicit in which experience could be described normatively and analytically: in short a language of ethics and science

How does this book relate to the Future of Media?

According to Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin - "The Greeks matter because some of them, at least, recognized that they were passing through a change in how people frame the world. In their case, it was the change from the oral to the written, and this is of course the subject of one of the Platonic dialogues, Phaedrus. In it, Socrates declares himself fully aware that human capacities can change, and that as memory is displaced or funnelled into print, a variety of changes may set in which affect not only how we know things, but also who we are as human beings.

Eric Havelock’s Preface to Plato shows that the Greeks were aware that there was some connection, perhaps even an all-embracing connection, among forms of communication, memory and thought. It’s quite fascinating to me that people should have this awareness of a sea change in their way of knowing, this self-consciousness about it." -- Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin in interview with Five Books

More:

https://fivebooks.com/best-books/todd...

The Creation Of The Media: Political Origins Of Modern Communications

by Paul Starr (no photo)

by Paul Starr (no photo)

Synopsis:

America's leading role in today's information revolution may seem simply to reflect its position as the world's dominant economy and most powerful state.

But by the early nineteenth century, when the United States was neither a world power nor a primary center of scientific discovery, it was already a leader in communications-in postal service and newspaper publishing, then in development of the telegraph and telephone networks, later in the whole repertoire of mass communications.

In this wide-ranging social history of American media, from the first printing press to the early days of radio, Paul Starr shows that the creation of modern communications was as much the result of political choices as of technological invention.

With his original historical analysis, Starr examines how the decisions that led to a state-run post office and private monopolies on the telegraph and telephone systems affected a developing society.

He illuminates contemporary controversies over freedom of information by exploring such crucial formative issues as freedom of the press, intellectual property, privacy, public access to information, and the shaping of specific technologies and institutions.

America's critical choices in these areas, Starr argues, affect the long-run path of development in a society and have had wide social, economic, and even military ramifications.

The Creation of the Media not only tells the history of the media in a new way; it puts America and its global influence into a new perspective.

by Paul Starr (no photo)

by Paul Starr (no photo)Synopsis:

America's leading role in today's information revolution may seem simply to reflect its position as the world's dominant economy and most powerful state.

But by the early nineteenth century, when the United States was neither a world power nor a primary center of scientific discovery, it was already a leader in communications-in postal service and newspaper publishing, then in development of the telegraph and telephone networks, later in the whole repertoire of mass communications.

In this wide-ranging social history of American media, from the first printing press to the early days of radio, Paul Starr shows that the creation of modern communications was as much the result of political choices as of technological invention.

With his original historical analysis, Starr examines how the decisions that led to a state-run post office and private monopolies on the telegraph and telephone systems affected a developing society.

He illuminates contemporary controversies over freedom of information by exploring such crucial formative issues as freedom of the press, intellectual property, privacy, public access to information, and the shaping of specific technologies and institutions.

America's critical choices in these areas, Starr argues, affect the long-run path of development in a society and have had wide social, economic, and even military ramifications.

The Creation of the Media not only tells the history of the media in a new way; it puts America and its global influence into a new perspective.

Raymond Williams on Culture and Society

by

by

Raymond Williams

Raymond Williams

Synopsis:

-The most important Marxist cultural theorist after Gramsci, Williams' contributions go well beyond the critical tradition, supplying insights of great significance for cultural sociology today... I have never read Williams without finding something worthwhile, something subtle, some idea of great importance-

- Jeffrey C. Alexander, Professor of Sociology, Yale University

Celebrating the significant intellectual legacy and enduring influence of Raymond Williams, this exciting collection introduces a whole new generation to his work.

Jim McGuigan reasserts and rebalances Williams' reputation within the social sciences by collecting and introducing key pieces of his work.

Providing context and clarity he powerfully evokes the major contribution Williams has made to sociology, media and communication and cultural studies.

Powerfully asserting the on-going relevance of Williams within our contemporary neoliberal and digital age, the book:

Includes texts which have never been anthologized - Williams' work both biographically and historically

Provides a comprehensive introduction to Williams' social-scientific work

Demonstrates the enduring relevance of cultural materialism.

Original and persuasive this book will be of interest to anyone involved in theoretical and methodological modules within sociology, media and communication studies and cultural studies.

Review and Commentary:

According to Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin - "This is an inaugural lecture Raymond Williams gave in 1974, when he assumed a professorship in drama at Cambridge University.

He’s one of the most fertile minds when it comes to media in the last century. Basically he’s saying that it’s extremely odd, and yet central, to the form of civilization that has evolved, that there’s so much drama.

And what he means by drama is not simply normal plays, but everything from advertising to television serials, to the contents of newspapers and magazines. He died in 1988 before a lot of the new technology we have now appeared; he had not encountered the iPhone.

But he anticipates a life in which people are immersed in narrative nonstop. I would add sound, or song, as another important component. This article is, at least to my way of thinking, the earliest statement of the point that quantity becomes quality.

The quantity of a certain kind of media experience creates a different way of life, which is in fact ours. Williams directed us into the whole problem of media saturation as a phenomenon worthy of treatment in its own right. -- Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin in interview with Five Books

by

by

Raymond Williams

Raymond WilliamsSynopsis:

-The most important Marxist cultural theorist after Gramsci, Williams' contributions go well beyond the critical tradition, supplying insights of great significance for cultural sociology today... I have never read Williams without finding something worthwhile, something subtle, some idea of great importance-

- Jeffrey C. Alexander, Professor of Sociology, Yale University

Celebrating the significant intellectual legacy and enduring influence of Raymond Williams, this exciting collection introduces a whole new generation to his work.

Jim McGuigan reasserts and rebalances Williams' reputation within the social sciences by collecting and introducing key pieces of his work.

Providing context and clarity he powerfully evokes the major contribution Williams has made to sociology, media and communication and cultural studies.

Powerfully asserting the on-going relevance of Williams within our contemporary neoliberal and digital age, the book:

Includes texts which have never been anthologized - Williams' work both biographically and historically

Provides a comprehensive introduction to Williams' social-scientific work

Demonstrates the enduring relevance of cultural materialism.

Original and persuasive this book will be of interest to anyone involved in theoretical and methodological modules within sociology, media and communication studies and cultural studies.

Review and Commentary:

According to Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin - "This is an inaugural lecture Raymond Williams gave in 1974, when he assumed a professorship in drama at Cambridge University.

He’s one of the most fertile minds when it comes to media in the last century. Basically he’s saying that it’s extremely odd, and yet central, to the form of civilization that has evolved, that there’s so much drama.

And what he means by drama is not simply normal plays, but everything from advertising to television serials, to the contents of newspapers and magazines. He died in 1988 before a lot of the new technology we have now appeared; he had not encountered the iPhone.

But he anticipates a life in which people are immersed in narrative nonstop. I would add sound, or song, as another important component. This article is, at least to my way of thinking, the earliest statement of the point that quantity becomes quality.

The quantity of a certain kind of media experience creates a different way of life, which is in fact ours. Williams directed us into the whole problem of media saturation as a phenomenon worthy of treatment in its own right. -- Journalism Professor at Columbia University - Todd Gitlin in interview with Five Books

A great interview with Todd Gitlin:

"After many years of writing about how news is composed, how entertainment is composed, who decides on them and who pays attention to them, I’d been discomfited with the academic habit of thinking everything is a text and thinking of everyone as a graduate student who has nothing to do except interpret texts.

When in fact, mostly people are not so much studying texts as they are immersed in them, careening through the torrential speed and volume of the 24/7 media society.

The media torrent is a phenomenon in itself. Which is not to say that it’s content neutral, that content doesn’t matter, but that there is this huge social phenomenon: namely that what people spend most of their time doing in our civilization (when they’re neither sleeping nor working) is connecting to media.

And actually they’re even relating to media during much of the time they’re ostensibly working.

I tried in the book to look at precedents but primarily I looked at the sheer proliferation of means of delivery, including sounds as an important element. So I quickstep through history, the history of saturation, the speed of communication change, and I write about navigational strategy – which everybody develops, whether they know it or not, in striving to manage the media torrent.

And what’s your conclusion?

You mean is this good for civilization?

Well you can’t unplug the media torrent at will.

This is our civilization, and I suppose I’m more concerned that people take seriously the immensity of this phenomenon, in which we’re immersed.

We have more experience of people via electronics than we have of face-to-face contact. I don’t view this with automatic alarm, or as an occasion for fireworks.

There are elements that are beneficial, there are elements that are sort of horrific. I can’t pretend to have a particular line on it, except saying, “There it is, we’d better stare at it.”

So do you discuss newspapers in the book?

I do. The crisis in advertising – in other words, in the financing of newspapers – overlays a longer-running decline. If you look at the US, time spent with newspapers has actually been declining for years, long before the internet.

So in 1966, 75 per cent of Americans said they read the newspaper either every day or most days.

By 1986, that figure was down to 51 per cent.

Among the under-30s, 60 per cent had said yes in 1966, by 1986 that was down to 29 per cent. There have been large shifts in sensibility, that didn’t just begin with laptops.

So I think we’re in some big cultural upheaval, and one feature of it is the premium on seeing things through pictures, and hearing things through sound, knowing the world in those ways.

And there’s a decline in reading newspapers, a decline in reading books, and the situation has been exacerbated enormously by the siphoning of advertising away from newspapers, and also by the inability of anyone to figure out how to monetize the internet version of newspapers.

Newspapers remain central to people’s diet of online-ness, but if it were indeed possible for newspapers to sustain themselves economically by figuring out how to exploit the availability of the internet, it would seem to me that someone would have figured it out by now. People have been thrashing around about this for years, asking, “Where’s the new business model for the newspaper?” And they haven’t found an answer.

In the meantime there are a proliferation of ways in which people can entertain themselves. We underestimate how much of newspaper consumption has always been undertaken for purposes of entertainment. Much of what people look for in a newspaper experience is a feeling.

We may think we’re reading it for information, but what we’re actually reading it for, as I argue in my book, is to have a certain kind of sensation – a disposable emotion. And now there are so many other ways to achieve that. Newspapers are competing with every other so-called delivery system that’s out there. The old world is going fast. I don’t mean it’s going to disappear, but newspapers are obviously very unstable and weakened.

I saw an article in the New York Review of Books recently suggesting that endowments might be a solution. What’s your view on the non-profit model?

There is on-going discussion at Columbia Journalism School about such matters. I will tell you my prejudice. I don’t think that non-profits can by themselves constitute a solution to the problem.

They are imperfect, more than imperfect: they are sluggish institutions. They can also be high-handed, there’s not a lot of democratic accountability.

Obviously there’s a place for foundation support, but I don’t see non-profits as an adequate alternative to government subvention of some sort.

The trick, as in Canada and elsewhere, is to insulate finance from control.

I think the Brits have pretty convincingly demonstrated that it’s possible to do it via the BBC.

Another model is Scandinavian countries, which subsidize newspapers without regard to their political positions. I don’t think anyone ought to be naive about the dangers of government support, but I do think we need to have some creative thinking about how to subsidize what is, after all, a national need.

Without a substantial change in the system of newspaper finance, we’re heading into a distressing bifurcation – high-level journalism for a very restricted public while everyone else eats cupcakes, or crumbs.

So your solution for the serious news, which people aren’t interested in, is some sort of government support.

We need multiple models. Private ownership is fine as long as the proprietors are willing to live with single-digit profits. I don’t think the news media should be exclusively government-supported. But the news is a public good, like an airline system in which planes don’t fly into each other.

The availability of intelligently compiled, serious information is a prerequisite for democratic life. So the question is not whether there should be public funding, but how to manage it, so that it doesn’t become Orwellian.

The above was discussing his book:

Media Unlimited: How the Torrent of Images and Sounds Overwhelms Our Lives

by Todd Gitlin (no photo)

by Todd Gitlin (no photo)

Synopsis:

Everyone knows that the media surround us, but no one quite understands what this means for our lives.

In Media Unlimited, a remarkable and original look at our media-glutted, speed-addicted world, Todd Gitlin makes us stare, as if for the first time, at the biggest picture of all.

From video games to elevator music, action movies to reality shows, Gitlin evokes a world of relentless sensation, instant transition, and nonstop stimulus.

He shows how all media, all the time fuels celebrity worship, paranoia, and irony; and how attempts to ward off the onrush become occasions for yet more media.

Far from signaling a "new information age," the media torrent, as Gitlin argues, encourages disposable emotions and casual commitments, and threatens to make democracy a sideshow.

Both a startling analysis and a charged polemic, Media Unlimited reveals the unending stream of manufactured images and sounds as a defining feature of our civilization and a perverse culmination of Western hopes for freedom.

A provocative new exploration of our media-saturated lives -a worthy successor to Marshall McLuhan's Understanding Media.

More:

https://fivebooks.com/best-books/todd...

Source: Five Books

"After many years of writing about how news is composed, how entertainment is composed, who decides on them and who pays attention to them, I’d been discomfited with the academic habit of thinking everything is a text and thinking of everyone as a graduate student who has nothing to do except interpret texts.

When in fact, mostly people are not so much studying texts as they are immersed in them, careening through the torrential speed and volume of the 24/7 media society.

The media torrent is a phenomenon in itself. Which is not to say that it’s content neutral, that content doesn’t matter, but that there is this huge social phenomenon: namely that what people spend most of their time doing in our civilization (when they’re neither sleeping nor working) is connecting to media.

And actually they’re even relating to media during much of the time they’re ostensibly working.

I tried in the book to look at precedents but primarily I looked at the sheer proliferation of means of delivery, including sounds as an important element. So I quickstep through history, the history of saturation, the speed of communication change, and I write about navigational strategy – which everybody develops, whether they know it or not, in striving to manage the media torrent.

And what’s your conclusion?

You mean is this good for civilization?

Well you can’t unplug the media torrent at will.

This is our civilization, and I suppose I’m more concerned that people take seriously the immensity of this phenomenon, in which we’re immersed.

We have more experience of people via electronics than we have of face-to-face contact. I don’t view this with automatic alarm, or as an occasion for fireworks.

There are elements that are beneficial, there are elements that are sort of horrific. I can’t pretend to have a particular line on it, except saying, “There it is, we’d better stare at it.”

So do you discuss newspapers in the book?

I do. The crisis in advertising – in other words, in the financing of newspapers – overlays a longer-running decline. If you look at the US, time spent with newspapers has actually been declining for years, long before the internet.

So in 1966, 75 per cent of Americans said they read the newspaper either every day or most days.

By 1986, that figure was down to 51 per cent.

Among the under-30s, 60 per cent had said yes in 1966, by 1986 that was down to 29 per cent. There have been large shifts in sensibility, that didn’t just begin with laptops.

So I think we’re in some big cultural upheaval, and one feature of it is the premium on seeing things through pictures, and hearing things through sound, knowing the world in those ways.

And there’s a decline in reading newspapers, a decline in reading books, and the situation has been exacerbated enormously by the siphoning of advertising away from newspapers, and also by the inability of anyone to figure out how to monetize the internet version of newspapers.

Newspapers remain central to people’s diet of online-ness, but if it were indeed possible for newspapers to sustain themselves economically by figuring out how to exploit the availability of the internet, it would seem to me that someone would have figured it out by now. People have been thrashing around about this for years, asking, “Where’s the new business model for the newspaper?” And they haven’t found an answer.

In the meantime there are a proliferation of ways in which people can entertain themselves. We underestimate how much of newspaper consumption has always been undertaken for purposes of entertainment. Much of what people look for in a newspaper experience is a feeling.

We may think we’re reading it for information, but what we’re actually reading it for, as I argue in my book, is to have a certain kind of sensation – a disposable emotion. And now there are so many other ways to achieve that. Newspapers are competing with every other so-called delivery system that’s out there. The old world is going fast. I don’t mean it’s going to disappear, but newspapers are obviously very unstable and weakened.

I saw an article in the New York Review of Books recently suggesting that endowments might be a solution. What’s your view on the non-profit model?

There is on-going discussion at Columbia Journalism School about such matters. I will tell you my prejudice. I don’t think that non-profits can by themselves constitute a solution to the problem.

They are imperfect, more than imperfect: they are sluggish institutions. They can also be high-handed, there’s not a lot of democratic accountability.

Obviously there’s a place for foundation support, but I don’t see non-profits as an adequate alternative to government subvention of some sort.

The trick, as in Canada and elsewhere, is to insulate finance from control.

I think the Brits have pretty convincingly demonstrated that it’s possible to do it via the BBC.

Another model is Scandinavian countries, which subsidize newspapers without regard to their political positions. I don’t think anyone ought to be naive about the dangers of government support, but I do think we need to have some creative thinking about how to subsidize what is, after all, a national need.

Without a substantial change in the system of newspaper finance, we’re heading into a distressing bifurcation – high-level journalism for a very restricted public while everyone else eats cupcakes, or crumbs.

So your solution for the serious news, which people aren’t interested in, is some sort of government support.

We need multiple models. Private ownership is fine as long as the proprietors are willing to live with single-digit profits. I don’t think the news media should be exclusively government-supported. But the news is a public good, like an airline system in which planes don’t fly into each other.

The availability of intelligently compiled, serious information is a prerequisite for democratic life. So the question is not whether there should be public funding, but how to manage it, so that it doesn’t become Orwellian.

The above was discussing his book:

Media Unlimited: How the Torrent of Images and Sounds Overwhelms Our Lives

by Todd Gitlin (no photo)

by Todd Gitlin (no photo)Synopsis:

Everyone knows that the media surround us, but no one quite understands what this means for our lives.

In Media Unlimited, a remarkable and original look at our media-glutted, speed-addicted world, Todd Gitlin makes us stare, as if for the first time, at the biggest picture of all.

From video games to elevator music, action movies to reality shows, Gitlin evokes a world of relentless sensation, instant transition, and nonstop stimulus.

He shows how all media, all the time fuels celebrity worship, paranoia, and irony; and how attempts to ward off the onrush become occasions for yet more media.

Far from signaling a "new information age," the media torrent, as Gitlin argues, encourages disposable emotions and casual commitments, and threatens to make democracy a sideshow.

Both a startling analysis and a charged polemic, Media Unlimited reveals the unending stream of manufactured images and sounds as a defining feature of our civilization and a perverse culmination of Western hopes for freedom.

A provocative new exploration of our media-saturated lives -a worthy successor to Marshall McLuhan's Understanding Media.

More:

https://fivebooks.com/best-books/todd...

Source: Five Books

Understanding Media

by

by

Marshall McLuhan

Marshall McLuhan

Synopsis:

This reissue of Understanding Media marks the thirtieth anniversary (1964-1994) of Marshall McLuhan's classic expose on the state of the then emerging phenomenon of mass media.

Terms and phrases such as "the global village" and "the medium is the message" are now part of the lexicon, and McLuhan's theories continue to challenge our sensibilities and our assumptions about how and what we communicate.

by

by

Marshall McLuhan

Marshall McLuhanSynopsis:

This reissue of Understanding Media marks the thirtieth anniversary (1964-1994) of Marshall McLuhan's classic expose on the state of the then emerging phenomenon of mass media.

Terms and phrases such as "the global village" and "the medium is the message" are now part of the lexicon, and McLuhan's theories continue to challenge our sensibilities and our assumptions about how and what we communicate.

Books mentioned in this topic

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (other topics)Media Unlimited: How the Torrent of Images & Sounds Overwhelms Our Lives (other topics)

Raymond Williams on Culture and Society: Essential Writings (other topics)

The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications (other topics)

Preface to Plato (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Marshall McLuhan (other topics)Todd Gitlin (other topics)

Raymond Williams (other topics)

Paul Starr (other topics)

Eric Alfred Havelock (other topics)

More...