Avi's Blog, page 13

June 6, 2023

Summer Blog Series: Mitali Perkins

From Avi: As I did last summer, I’ve invited 13 admired middle grade authors to write for my blog for the next three months. I hope you’ll tune in each Tuesday to see who has answered these three questions. You should have a list of terrific books to read and share and read aloud by the end of the summer … along with new authors to follow!

Your favorite book on writing:Lately I have been using Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody, which has helped me with my main writing struggle—structure.

Reading aloud from my books:

Reading aloud from my books: I’d start with Rickshaw Girl (Charlesbridge) if you want to read a book of mine aloud. I’ve been told that it’s a good family read. It’s been adapted to a film, too!

Where do you write most often?

Where do you write most often?

Here I am right now writing on my patio in California, and this is my view. Am I blessed or what?

Instagram Twitter Home

Instagram Twitter Home

Mitali’s newest book, available July 11, 2023!

May 30, 2023

Summer Blog Series: Avi

As I did last summer, I’ve invited 13 admired middle grade authors to write for my blog for the next three months. I hope you’ll tune in each Tuesday to see who has answered these three questions. You should have a list of terrific books to read and share by the end of the summer … along with new authors to follow!

Your favorite book on writing:The one book about writing that I have found most helpful to me is Aspects of the Novel by E.M. Forster. (Among his own illustrious and well-known novels are Passage to India, Howard’s End, A Room of One’s Own.) Based on a lecture series Forster gave in 1927, the seven aspects he discusses are story, people, plot, fantasy, prophecy, pattern, and rhythm.

In no sense of the word is this short volume a “how to do” book. Rather, Forster presents ways of thinking about the novel, broken down into its various aspects. That said, if he gets you to think about those aspects slightly differently than you usually do, it may help you extricate yourself from particular problems. They are also helpful when thinking about the novels you are reading. The fact that these were lectures delivered almost a hundred years ago in no way detracts from literary wisdom.

Reading aloud from my books:

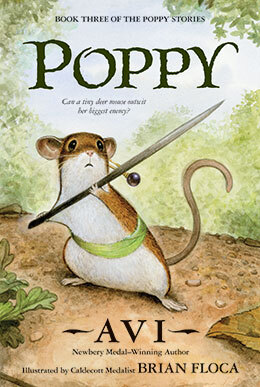

Reading aloud from my books: Of all my books which teachers, librarians, and parents tell me they most enjoy reading aloud to kids, are my Poppy books. In fact, I have heard from many who have read the whole series to their students in the course of a year.

Though the books were not composed in sequence, the seven books as they exist today, have an over-arching storyline, beginning with Ragweed and ending with Poppy and Ereth, seven books in all.

That said, many readers begin with the third (and shortest) book in the series, Poppy. In particular, kids enjoy the nonsense swearing by the grumpy Ereth the Porcupine.

For older kids, the two-volume Beyond the Western Sea, with its short chapters and cliff-hanging structure seems to engage many—including adults.

Where do you write most often?

Where do you write most often?

Facebook Instagram Blog Home

Facebook Instagram Blog Home

Avi’s newest book!

May 23, 2023

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum

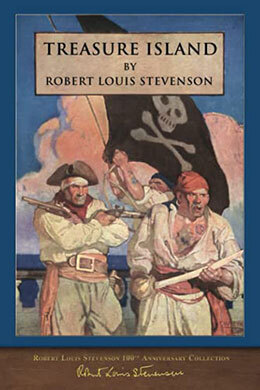

Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894), first published serially under the title, The Sea Cook, has enormously impacted me since I first read it as an adolescent. Written, as the original subtitle had it, “for boys,” it has been the hallmark of all pirate tales, and many other adventure stories since it first appeared. It was not, curiously, highly successful as a serialized story, but when it appeared with a new title in book format, it established Stevenson’s high reputation.

Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894), first published serially under the title, The Sea Cook, has enormously impacted me since I first read it as an adolescent. Written, as the original subtitle had it, “for boys,” it has been the hallmark of all pirate tales, and many other adventure stories since it first appeared. It was not, curiously, highly successful as a serialized story, but when it appeared with a new title in book format, it established Stevenson’s high reputation.

For those who don’t know the story—if such is possible—it concerns the buried treasure of Pirate Captain Flint on a remote island (the location carefully not cited) which his old crew is determined by hell or high water to recover. Simultaneously, two British gentlemen, Dr. Livesey and Squire Trelawney, are equally determined to get it. They are aided and abetted by young Jim Hawkins, who lives the adventure of a lifetime and is the essential narrator of the story. So it is Jim’s book in deed and word.

I cannot attest to the accuracy of all its rich nautical terminology, or ways of a ship, but suffice it to say it reads with the presumption of great knowledge. That goes for all the verbal wordplay, which is as dynamic as it is captivating. Indeed, the sheer energy of the book is quite breathtaking. It is truly a non-stop adventure.

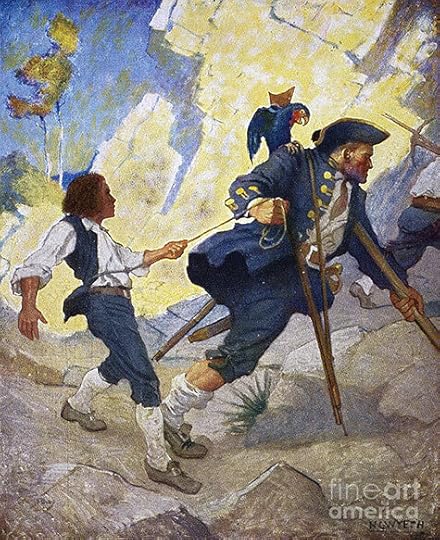

illustration of Jim Hawkins and Long John Silver from Treasure Island

illustration of Jim Hawkins and Long John Silver from Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911

But while the boy, Jim, is the book’s protagonist, the portrayal of Long John Silver is the great triumph of the book. To describe him as charismatic is but half his fascination. A wonderful talker, sly, evil, a liar, generous, funny, clever, he is altogether wonderful to behold, a one-legged man who (metaphorically) out-races all the other characters in the book. It’s not that Jim is a poor or dull character, it’s that Long John Silver is a brilliant creation. When I first read the book—and again, just recently—it is he who gives the story its greatness.

That said the other characters are wonderfully presented, Captain Billy Bones, Blind Pew, and many more are all quite fine. And if you can get hold of the old Scribner edition of the book—it has been reprinted—with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth, you’ll be even more rewarded. For years I had a reproduction of Wyeth’s portrait of a desperate Blind Pew over my writing desk. Oh, if only I could write a book and character like that!

illustration of Blind Pew from Treasure Island

illustration of Blind Pew from Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911

But there is a secret in the book which is right there in the open for all to find. The treasure that the pirates are after is stolen loot. The pirates are murderous scoundrels. Their only claim to the treasure is that they took it by theft and murder.

That said, Dr. Livesey and Squire Trelawny, the English gentlemen who go after it, have no claim to it either. They are not interested in giving it back to those who lost it even though there is a record (in the story) of when and where it was stolen. What does Trelawney say? “We’ll have favorable winds, a quick passage, and not the least difficulty in finding the [treasure], and money to eat—to roll in—to play duck and drake with ever after.” Indeed, the gentlemen will get the treasure via their own theft and murder.

In the end, it is Long John Silver, alone among the pirates, who escapes to his freedom. Stevenson was not about to hang his glorious creation. No fool he.

Read Treasure Island.

You’ll be singing:

Fifteen men on the Dead Man’s Chest

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

May 16, 2023

Words, words, words

Polonius: What do you read my lord?

Hamlet: Words, words, words.

The English language—of all the world’s languages—has the largest vocabulary. It does so because it has absorbed many languages from different cultures and tongues. Moreover, it is sufficiently flexible and expansive (and widespread) so as to continue to add new words. Each year The Oxford Unabridged Dictionary adds new words that have gained general currency.

Now, we generally know William Shakespeare (1564–1616) as the preeminent writer of the English language. If you went to a traditional high school you probably read (laboriously) Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, or Macbeth.

(For that reason, whenever my children were reading these plays in school, I always secured a film edition of the play, on the theory that as modern kids they could make more sense of the language when they could see the words attached to an action. Indeed our youngest grew so fond of Leonardo DiCaprio’s very modern gangster (but full text) version of Romeo + Juliet that he watched it over and over again.)

photo: Abhishek Gaurav, Pexels

photo: Abhishek Gaurav, PexelsBut what we sometimes forget is that Shakespeare was an extraordinary inventor of new words, words that entered the mainstream of our vocabulary so that we use them today as a matter of course. Here are just a few of them.

Bandit

Critic

Dauntless

Dwindle

Green-Eyed (to describe jealousy)

Lackluster

Lonely

Skim-milk

Swagger

Uncomfortable

Unearthly

Unreal

If you go online you can track many, many, more.

He also created phrases that are equally vital to the language:

As good luck would have it

Break the ice

Cold comfort

Come what may

Devil incarnate

Eaten me out of house and home

Fair play

A laughing stock

In a pickle

And, again, many, many, more.

What I find remarkable about this is that in Shakespeare’s time, reading was not a universal skill. Far from it. So when these words and phrases were first set forth in the Globe Theatre, they were heard not read.

We sometimes take language as a given. As speakers, as writers, we all search for the right word to express ourselves. I am constantly using a thesaurus. What we sometimes fail to recognize is that a reader—a good reader—develops a vocabulary that enables them to effectively express and communicate their ideas, feelings, and beliefs. When we have the words, we can share our thoughts and feelings.

“A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” says Juliet, but when you say “rose,” you have shared your thought.

May 8, 2023

Series and Sequels

It’s not unusual for me to get a note from a reader asking me to extend the life—if you will—of a character in one of my novels or stories with a new tale. I take it as a compliment that the reader was so engaged with that character that they wanted more. I’ve done so rarely, but over the course of my writing, I’ve composed a few sequels and some series, which is not quite the same thing. Here’s a showing of all my stories in this category.

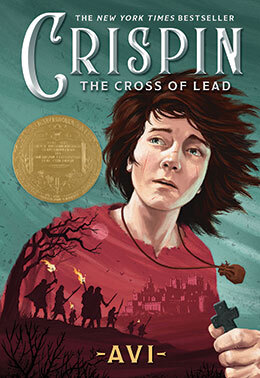

In only one instance did I plan to write a series (the Crispin books), but I was never given the opportunity to write the last and concluding volume. It was made more complicated by the series being split between different publishers. Still, someday I’d like to write that concluding volume. I do have the plot in my head.

The Beyond the Western Sea books were never meant to be two books, but one. The publisher felt they would be better received as two books, a decision with which I concurred, but in retrospect, came to regret. Moreover, the way the books were promoted, many readers thought a third volume was to come. At one point I agreed to do it, but it was never written.

The Poppy books, seven in number, were not written (and illustrated by Brian Floca) in sequence and they took twenty-five years to complete. It was not so much to tell an extended story that drew me back time and again, as it was my affection for the characters that inspired me to write the multiple volumes. The truth is, it was great fun to write about Poppy and Ereth and the other Dimwood Forest characters. To coin a phrase, when writing is fun, it’s done. I have mused about doing yet another, but I think seven is enough.

The End of the Beginning and A Beginning a Muddle and an End, share the same characters, and having fun with language, but there is no extension of a story.

Midnight Magic, Murder at Midnight, and City of Magic share the same main characters but are all stand-alone tales.

Now I am about to publish a sequel to The Secret School. Titled The Secret Sisters, it is very much a true sequel, insofar as it extends Ida’s (the main character in the first book) story logically and expansively—not just about what happens, but the growth of Ida’s life and being.

That said, writing a true sequel is complex. To begin The Secret Sisters, I had to go through The Secret School and set down all the factual material I had created—twenty years ago—created without any notion that the story would go on. Some examples: How old are the characters? What did they look like? What are their names? What are their relationships? How did they dress? How did they talk and were there any expressions that they used as a way of giving life to the characters? And so on.

Since Ida’s first story is rooted in a specific time and place (rural Colorado 1925) all of those aspects had to be continued, even as the characters had to evolve to become more in an engaging way. All those first-book factors were but starting points if I desired (and I did) Ida to grow.

That said, even as drafts of the book emerged, the editor and copyeditor would bring to my attention some missteps. “In book one, you said it was five miles to that place. Here you are saying it’s six.” If they had not spotted those mistakes, you may be sure readers would have—and let me know about it.

All in all, the writing of sequels is evenly balanced by some things: certain basic factors have been established so you don’t have to invent them. And readers do find pleasure in a return to characters for whom they have developed affection. At the same time you must extend those characters’ live so as to make the stories sufficiently engaging to read.

As the writer, I loved expanding Ida’s life and story.

My hope is that readers will find that to be true for The Secret Sisters.

May 2, 2023

Story Behind the Story: What Do Fish Have to Do with Anything?

What Do Fish Have to Do with Anything?

What Do Fish Have to Do with Anything?A good number of years ago I had accepted the invitation to speak at a literary conference, in Seattle, if I remember correctly. It was only after I had agreed to be there that I was told of a somewhat unusual requirement; Each year of the conference a literary volume was put together. All attending writers and illustrators were asked to contribute to that collection. That is why I sat down and wrote the story, What Do Fish Have to Do With Anything?

The inspiration? The notion of writing about a lonely boy and a homeless man are subjects that are, alas, everywhere to see.

It was hardly the first short story I had written, and when they come about they do for a variety of reasons, not connected. Thus, in the same volume, The Goodness of Matt Kaizer came to mind because I knew a teacher who was also the wife of an Episcopalian minister. She told me how the children of such folks often have a hard time trying to establish themselves (in school) as distinct from their parents’ religious convictions and morality. I found an ironic twist to that situation.

Talk to Me came to me when I experienced a phone message I kept checking only to learn it had simply never been erased.

What’s Inside was written for a collection of stories about guns that a friend of mine was assembling.

And so forth.

This particular anthology came about when the editor I had been working with for a number of years fell into difficulties such that I could no longer work for him. At the same time, an editor for whom I had written a story for another short story group, asked me if I’d put together a new volume of my own short stories. Since I had already written and never published a few I agreed, and we worked together to create this collection.

Short stories, I find, are hard to write, but both fascinating to work on, and when successful, enormously satisfying. It was Edgar Allan Poe (a major writer of short stories) who first tried to delineate what the short story form was. In the Twentieth Century, the short story became a staple of American literature and was published in an astonishing array of magazines for a huge readership.

Those days are gone, but happily short stories are still being written and enjoyed.

April 25, 2023

A Letter from the Editor

One of the standard forms of communication between a writer and publisher is the editorial letter. It works this way:

One of the standard forms of communication between a writer and publisher is the editorial letter. It works this way:

You’ve worked on your book for a year—probably more—and you’ve submitted it to your publisher, which is to say an editor. If the book is accepted, you will, in time, get what is called an editorial letter, which, in essence, is the editor telling the writer how to make the book better.

I have worked with many editors. The best editors are trying to help the writer achieve the full possibilities of the work. Poor editors (I’ve worked with a few) try to bend the book to their vision of your book. Not much fun.

In all my years of publishing only twice has an editor not sent such a letter.

It was with the late, great, Richard Jackson. It was the first time I worked with him, and the book would become SOR Losers. When the text was sent to him, he let me know he felt it was good enough to pass right on to the copyeditor, that’s to say, to start the publication process. I was startled. Did this guy know what he was doing?

So, I objected. I said I thought the book needed more work and made suggestions. He agreed and we went on in regular fashion. Indeed we worked on many books together, and never again did he ignore an editorial letter.

The other time, the editor informed me (do you remember the day of telephone conversations?) she didn’t believe in sending such a letter, but simply told me what she liked about the book I had written and then returned the submitted manuscript with notes for revision right on the text.

But most of the time I’ve gotten an editorial letter as I just did yesterday, for a new book. The letter is four pages, single-spaced. From my experience that is somewhat short.

The letter begins—they all do—with positive remarks about the book, what she thought was the strength of the text. This is important because it gives me confidence that I’ve done something right, and just as vital, I know what the editor thinks is the strength of the text, and I can work to that.

After that introductory section, most of the letter has suggestions as to how to make the book better. Let me stress that word, suggestions. These are not commands, as in “When you do this then I will publish the book.” Indeed, I’m being encouraged to talk to the editor about any of these ideas.

That said, in my early days, I received directives about changes necessary if publication was to take place. One editor—I kid you not—once said to me, “It needs about five more words.” (That book would eventually become The End of the Beginning) Most of the time the requests are for much, much more.

I have never argued about these suggestions. If I disagree with a particular idea, I try to understand the reason for the perceived problem and make changes so as to deal with it in a different way. I am therefore not ignoring the problem as I am finding an alternate way to resolve it.

By and large, I am happy to use the editor’s suggestions about revising the work. I am making the book better. Let it also be said, revising a work is—at least for me—the most enjoyable part of the writing process. I know the work will be published and I know I’m making a better book. Indeed, as I revise, I sense the book is getting better. I also love working with editors. Not infrequently, working with an editor brings out massive improvements.

Also, as I submit revised drafts of the book, I may well receive more editorial letters.

In all of this, it is important, I think, to stress a vital fact about the publishing process: the writer is NOT working alone. It’s a deeply collaborative process. In many a book—on the copyright page, or elsewhere—the book’s graphic designer is cited. So too is the artist who created the cover. They should be. But it is rare to see the editor cited unless the editor has achieved such prominence as to have the book referenced as “A Richard Jackson Book.”

Editors should be cited too.

Someday someone will be smart enough to publish a collection of editorial letters. It will be a revelation, a masterclass on the writing of good books.

April 18, 2023

The Phantom of the Opera and Rereading

As I write this—April 16, 2023—Andrew Lloyd Weber’s musical, The Phantom of the Opera, will end its New York City Broadway run—the longest run in theatrical history, with 13,981 performances. It began in January 1988.

I must have been one of the few people not to have seen it, but a vast number have. One person saw it sixty-nine times. Another one hundred and forty! Another made a life by seeing it performed in many countries but was most impressed by the one he saw in Sweden, because, he said, it was done “differently.” Someone had the street address of the theatre tattooed on her arm! These folks call themselves “Phans.”

All this was reported in the New York Times .

There are parallels with books. I once met someone who told me he read the entire Harry Potter series six times. I have met folks who have read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice often—these folks call themselves “Janeites.”

In pursuit of data to support this essay, I checked, and there is currently posted a Goodreads review of my The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle, in which the reviewer indicates she read the book sixteen times.

As I have confessed in this blog, every Christmas I reread Dickens’ The Christmas Carol. That’s—another confession—a lot of Christmases.

I’m sure many of us know young readers who reread their favorite books a fair number of times. How many of you have read a favorite picture book to a young reader so many times you could and perhaps do so with a weary heart?

What does one get with rereading? If one has been engrossed with the plot so much that you are turning the pages at a fast flip, you may miss many of the nuances of a beautifully written text, and indeed aspects of the plot. There are real joys in what might be called slow, attentive reading, often best found when rereading.

But there are negative aspects. When I first read Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, the writing fascinated me. A reread only brought me irritation by way of its mannered style.

I recently reread Dickens’ Great Expectations—which I first read in my twenties. A reread astonished me by how much of the book is about abuse, pounded out, and received. Virtually every character is touched by this cruelty. When I first read it (in the 1950s) I may not have even known what the term abuse meant.

By the same token, as we have been informed and educated about racism, misogyny, and prejudice of one kind or another, rereading may inform us about critical things we have missed.

Of course, when writing, I am constantly re-reading my own work, forever (so it feels) finding things to make better. Indeed, if I have reason to reread one of my own books (published years ago) I inevitably find things I could have improved. No surprise: I don’t like to reread my own work.

All that said, the return to a text which was moving, or meaningful in other ways, can be a deep comfort, a kind of literary comfort food, or even a revival of vital wisdom. It can be like a visit with an old friend, a return to a place that fills you with fond memories, a reminder of the good things in life.

There are lots of lists of fine books to read. How about a list of books worth rereading?

Does anyone care to share?

April 11, 2023

Wow!

As a writer of historical fiction and a former librarian, research has not been difficult for me and, in fact, I enjoy it. I also read (and have taught myself) a good bit of history. It is easy, then, for me to locate information and facts. But when setting a novel in a historical setting the issue always becomes what fact, what way of thinking, being, and talking, contributes to the story. Simply providing a fact without having it be intrinsically part of the story, converts the story into a textbook, something I don’t wish to do.

Because there are many ways to write historical fiction, a simple definition is hard to come by. In this context, I suggest you read: https://historicalnovelsociety.org/defining-the-genre-what-are-the-rules-for-historical-fiction/

One of the more intricate questions a writer of historical fiction must deal with is language. English, which has the largest vocabulary of any of the world’s languages, is constantly evolving, even as it has always absorbed words from other languages—which is why it has such a large dictionary.

One simple example; blunder, has evolved from the Old Norse word, blundra, which meant to shut one’s eyes. Even in this one word, you can make sense of the evolution of the word from past to present.

My Newbery book, Crispin: The Cross of Lead, is set in 14th Century England. This is the time of Chaucer, and the English that was spoken is referenced as Middle English. Here is the way Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales begins:

My Newbery book, Crispin: The Cross of Lead, is set in 14th Century England. This is the time of Chaucer, and the English that was spoken is referenced as Middle English. Here is the way Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales begins:

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licóur

Of which vertú engendred is the flour;

Aside from the fact that I can’t speak Middle English, and struggle to barely understand it, there was no way I could write the book in the English of that day. What I chose to do was learn the standard metrical form of English poetry of the day and attempt to replicate it so as to give the text a sense, a feeling, if you will, of another way of talking English.

All this is further complicated by the nature of my readers, for the most part, middle-school-age young people. Their vocabulary is—I have little doubt—often different from mine.

That said, I remember a writer of middle-grade fiction who once told me he had located a McDonald’s in his neighborhood. He often went there shortly before three-o-clock, took over a booth, and ordered himself a hamburger and soda. Then he waited for the post-school crowd to swarm in, and then he listened and took notes as to their way of talking, their slang, their new words, their exclamations.

There are all kinds of research.

One of the ways I deal with this is to have the Oxford Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language on my computer. Of enormous value is that it contains a Historical Thesaurus. This allows me to winnow words that were not used in a particular period of time. When I am writing I often check to see if the word I use was used at the time.

Thus, I am currently writing a historical novel that takes place in the American West in 1893. In the course of the story, something important and unusual happens. I have my character say, “Wow!”

I stopped and checked that word in the Historical Thesaurus. When did “Wow!” enter the English literary world?

It seems it was in 1513.

April 4, 2023

This Blog and You, the Reader

On March 7, 2012, I began this blog with this remark:

On March 7, 2012, I began this blog with this remark:

“I am working on a new book. It’s so new it has no title, and to be honest, I’m not sure what will happen. Certainly, no ending is in sight. But it’s different, I think than anything I have written before, so I’m having a good—if hard—time.”

What’s amusing about this—or perhaps awful—I could write the same post today. Eleven years later, I’m working on a new book, not sure what will happen. I’m having a good—if hard—time.

The point is I’ve been writing this blog for eleven years (Over this period of time I’ve written some fifteen books) and it has attracted a fair number of readers. Perhaps it’s time to ask, what do you think of it? Is it worth reading? What do you like about it? What don’t you like about it? Are there things you would like me to address? Things I should avoid?

I’d love to hear from YOU.

Most sincerely,

Avio

Avi's Blog

- Avi's profile

- 1703 followers