Avi's Blog, page 9

March 12, 2024

Early Reading

It was purely a coincidence, but the other day I met up with two people — both adults — and the chat got around to early reading. They both reminisced about something important that happened to them some forty, fifty years ago — when they were in elementary school. They were recalling when a specific teacher had read a specific book to their classes. In one case, it was Black Beauty (written by Anna Sewell). The other book was Where the Wild Fern Grows (written by Wilson Rawls). These folks remembered the books and the teachers — and the reading — and considered them memorable moments in quite young lives, a sense that something changed for them.

When I asked what had changed, they were rather vague, except they knew it had been a deeply felt experience.

I have heard of such experiences many times, an adult recalling both a specific book and a teacher from forty or fifty years ago. Never forgotten.

What had happened?

I am neither an expert in reading nor psychology, but I suspect what occurred was a sudden opening of the world, a shift from an inward-looking sense of young self to an awareness of a vastly bigger world. An exhilarating shock. Mind, it was not just the text being read, but a teacher giving life to that text. Because no doubt the teacher was capable of reading that text and bringing it to vibrancy better than the child could do at that time.

If you are reading this blog of mine, I think I can assume you are interested in books and reading. So, we all know the value of books, from simple (wonderful) entertainment to providing information, even to just a nice way to pass the time. And more. But I don’t think we pay enough attention to what such a book reading does for the young.

Books can provide an explosive awakening, shifting the perspective from a self-centered vision to being other-centered, making the world vastly bigger than it was before that reading. I suspect the shock of that thrilling discovery is what makes that teacher-book moment so remarkable. And it is remembered as such.

I further suspect that it is not fully grasped at the moment. Yes, both the folks I was speaking to, described that it was “exciting” to hear those books read. But there is some mystery to this. Why this particular book? Why that particular teacher? Why that particular day?

I don’t think such events can be planned, much less anticipated. But they happen. Life-altering moments — brought on by a book.

Have you had such a moment, such a teacher, such a book? I invite you to share it with us.

March 5, 2024

See it. Listen to it.

I don’t consider myself deeply knowledgeable about movies. I enjoy the good ones and am bored with the dull ones. I find most films adapted from novels not nearly as fulfilling as the text narratives.

The films I find most intriguing are the ones that tell a story in a cinematic way. I love a film like Chaplin’s Modern Times because it tells its story in terms of what one sees without words. To watch the little tramp on an assembly line allows us to see a life—I think—in a unique way. What most interests me about movies is the different ways a story is told—text as contrasted with film.

I recently saw the movie called Zone of Interest, (based on a book by Martin Amis) which is one of the most unusual films I have ever seen, and, not beside the point, one of the most disturbing. It has been nominated for 5 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.

The story is about the German Commandant [Rudolf Höss] of the notorious Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland during World War Two. The commandant and his wife, Hedwig, and their children are living a “normal” middle-class life just behind the wall of Auschwitz. We see the walls, and the barbed wire above the walls.

Their family life is in no way unusual, except they are living right next to horrific atrocities. 1.1 million people were murdered next door. Very slightly do we understand that these people do know what is happening, but just barely. Rudolf Höss, who runs the camp sweetly reads to his children at night. An older brother locks his younger brother in a greenhouse. It is innocent fun until the old boy makes the hissing sound of poison gas. The wife models a fur coat taken from a prisoner who has just been murdered.

Most powerfully, as we watch the ebb and flow of the family’s ordinary life, we hear what is happening beyond the camp walls: screams, gunshots, commands, “Go drown him in the river.” At a distance, we see smoke rising from the oven smokestacks in which thousands of murdered people are being cremated, at times two thousand an hour. We see a passing train that contains humans being led to slaughter. We don’t see the people, just the train.

The film is about the capacity of people to ignore — or so they act — the terrible things that are being done to their fellow human beings. We are not shown the terrible things, rather we hear them and see the evidence from a distance. It shows us that even as we continue our lives, we often are, at some level, aware of what is happening and choosing to ignore it.

The film, unlike a written story, shows and sounds how evil happens — by acting as if it did not exist. It’s an extraordinary piece of narration in which mere words won’t do.

See it. Listen to it.

February 27, 2024

Publishing after Covid

While in many respects the Covid pandemic is behind us (but not, sadly, completely) it has had a long-term impact on many aspects of our society. That includes the world of books and publishing and the people who create them.

At first, there was an overall increase in books sold even though there was a decrease in bookstore sales. Indeed, at first, there was a reported increase in reading. The explanation: people staying home and an increase in online sales becoming the primary way readers purchase books.

At the same time, there was a big drop in trade book sales, which meant the author’s income declined, along with a radical drop in the author’s freelance work and speaking engagements — conferences, and school visits. These speaking engagements not only contribute to writers’ income directly, but they also promote their books — which bring sales.

I can relate to some of this in terms of my own experience. My Gold Rush Girl was published just as the pandemic exploded. I had an extensive book tour planned to share and promote the book, only to have it all canceled, the cancelations coming day after day until the whole tour vanished. To be sure I cancelled some of them myself. The tour was never revived.

Elsewhere, my in-school visits vanished even as schools themselves closed down. Virtual visits did increase and while they are fine, they are not the same (or as much fun) as face-to-face meetings.

The way publishing houses work also changed. The short of it was — as elsewhere — in-house office work adjusted. One of my editors who worked for a NYC publisher moved to the west coast. Another editor, though on the East Coast, at first stopped going into her office, and then, as the pandemic eased, went in only for a couple of days per week. Another editor I knew only went to the office for two days every three weeks. Even as the high point of the pandemic faded, these patterns of work continued.

After the main brunt of the pandemic was over, I went to one of my editor’s offices. The very large office complex was astonishingly empty (a great contrast to what it had been before) and when I got there, I had a long wait to find someone who could find my editor — another long wait.

I don’t work in such offices, but over the years I’ve been to visit many for meetings, and they were always busy places. No longer. It’s hard to believe that the lack of immediate interaction among book-making colleagues has not changed the dynamics of publishing, and not for the better. Publishing has famously been collaborative.

Then there is the issue of young readers themselves. With schools and libraries shut down, there was a huge shift to online instruction, which obviously includes reading. But digital reading is far less effective in terms of comprehension, fluency, and for that matter pleasure. Social media following grew greatly. It’s hardly a surprise that in the world of middle school reading (my world), the biggest growth has been in graphic books. I have nothing against graphic novels (My City of Light, City of Dark is one of the early ones), but these books are not primarily of a literary nature, which is the universe I inhabit.

Then there is the explosion of self-publishing.

Publishers Weekly reports: “According to Bookstats, which collects online sales data in real-time from Amazon, Apple, and Barnes & Noble across the print book, e‑book, and digital audiobook formats, self-published authors captured 51% of overall e‑book unit sales last year and more than 34% of e‑book retail revenue, compared to 31% in 2021.”

In 2011 there were 526,907 self-published books.

In 2021: 2,298,004.

I recently spoke to a long-term and successful editor. I asked, “Where do you think the world of publishing is heading?”

She laughed and said, “I have no idea.”

I didn’t laugh.

February 20, 2024

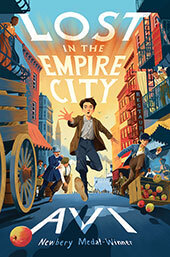

Lost in the Empire City

Over the years I have written something like eighty-five books, novels, short stories, and even a few picture books. Though I have lived for significant periods in many large cities: Chicago, Providence, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Denver, London, and Venice, my childhood was spent in New York City. But when I visit — rarely now — I’m very comfortable there. What I most enjoy is walking about and just looking, taking it all in. As my grandfather used to say, “They will never finish building the city.”

I loved (still do) to ride the Subways. I was about seven years old when I began to ride them alone, often working my way to the first car, so I could watch the endless fascinating tunnels with their ever-changing safety lights and passing trains roaring by. When in high school I rode them every day.

Although I have not lived there for something like fifty years I confess, I still consider myself a New Yorker. So it’s no surprise that ten of my books have meaningful New York City settings.

Catch You Later, Traitor City of Orphans Seer of Shadows Mayor of Central Park Sophia’s War Abigail Takes the Wheel City of Light, City of Dark Who Was That Masked Man Anyway? Iron Thunder Don’t You Know There’s a War On?

My forthcoming book — Lost in the Empire City — is set in 1911 New York. It treats of the love of family, immigration, the Lower East Side, the West Side, crime, and corruption — often common New York themes. [“Empire City” is but one of the city’s nicknames said to have been first coined by, of all people, George Washington.]

The novel takes place in the first decade of the twentieth century when there were still more horse-drawn vehicles than motor cars. It also references the subway system, which first began running in 1904, and was still relatively new. That first decade was also a time of massive immigration. Indeed, the Lower East Side was perhaps the most densely crowded city area in the world, with a gigantic and packed tenement population. There was also great wealth, extreme poverty, and bad health. Corruption and crime were rampant.

The Lower East Side was the area in which my immigrant forefathers came and lived. After I finished my mid-west college years I returned to New York and eked out a living, of sorts, in that same Lower East Side, along one of those alphabet avenues, A, B, C — I know longer know which. As I tried to be a professional writer — I was writing plays in those days — I lived in a fifth-floor walk-up, tiny two-room apartment, which might well have been there in the early twentieth century. The bathtub was in the small kitchen, and when I put a board over the tub, I had my table. Why was I living there?

As I recall the rent was thirty-two dollars a month. At some point, one of my college friends moved in. I would later move uptown, where the rent was sixty-five dollars.

So, all-in-all, the writing of Lost in the Empire City was like a return to my old home, not without its stresses, but considerable comfort and joy all the same. It has always been an adventure for me. It still is. Hardly a surprise this new book is an adventure, stretching from rural Italy to the sidewalks and fire escapes of New York City.

Here’s hoping you’ll visit.

February 13, 2024

Immigrants or descendants of immigrants

Never mind the intense debates about immigration to the USA, unless you are a decedent of North America’s indigenous peoples, we are ALL immigrants or descendants of immigrants. Even my wife — one among the millions who can trace her family history back to the Mayflower — fits within that category. But coming to the Americas has a very long history.

It was in the year 985 AD that Vikings came to North America and established the first European settlement in Newfoundland. It does not appear to have been permanent and is known primarily by some archeological evidence.

Five hundred years later, in 1497, John Cabot, whose Venetian birth name was Giovanni Caboto, sailing with a commission by the English King Henry VII, set down two claimant flags, an English flag, and a Venetian flag, also in Newfoundland. But again no permanent settlement was created.

It’s generally accepted that only in 1565, with the creation of St. Augustine [Florida] the oldest continuously occupied settlement of European and African American origin in the United States came into being. That’s forty years or so before the Jamestown and Massachusetts English settlements were created.

That said, from the 16th century on, immigrants have been coming to what is now the USA. Millions came, each with their own story. Most came voluntarily, but there were many who came in chains — slaves and felons. It was in 1619 that the first slaves came to Virginia, some twelve and a half million. A hundred years later, in 1719, the English government began to use transportation to the colonies as a legal punishment for felons. It is estimated that 50,000 of them were brought to the colonies of Virginia and Maryland.

[My 2019 novel, The End of the World and Beyond, is about this aspect of American history]

It is said that in 1785 George Washington referred to New York City as “The seat of the Empire,” meaning the American Empire. He also spoke of the city as the “pathway to Empire.” Hence the city’s nickname “Empire City.”

All of this sits as background for my forthcoming middle-grade novel, Lost in the Empire City. It’s an early 20th-century story about an Italian boy who immigrates to America only to be separated from his family upon arrival at Ellis Island. How he struggles to survive and find that family in New York City is the essence of this adventure tale. It will be published on the 2024 Fall list by HarperCollins.

The cover art is by David Dean. You’re the first to see it. It’s not even up on the bookstore sites yet.

February 6, 2024

Getting Used to Rejection

If one is a writer one of the things you get used to is rejection. It’s never pleasant but can be memorable. And sometimes, in retrospect, even funny.

When my mother learned she was giving birth to twins (my sister and I) she employed a nanny to help her. (There was already a two-year-old in the house — (my brother) — and my father was away at graduate school.) At the end of the first week, after I had been brought home, the nanny quit. The family story is that she said, “It would hurt my reputation to have been in a household where a baby [me] died.”

In kindergarten, my very first report card was issued. I received “Satisfactory“ in “sitting, standing, walking, and respecting the rights of others.” But for “use of handkerchief” I got “Unsatisfactory.”

[Edward is my birth name.]

For most of my elementary school days, I was in the same class with my twin sister. It was not unusual for me to hear, “That’s wrong. Let’s see if your smart sister has the answer.”

I had already flunked out of the first high school to which I went. When in the second, a private school, the English teacher called my folks and said “Avi is the worst student I have ever had. If you wish to have him continue here, he will need a writing tutor.”

In college, already having decided to be a writer, I asked an adult mentor to read some of my writing. “Lee, what do you think of my stuff?” “Well, Avi, it takes a heap of manure to make a flower grow.”

Editor: “I am turning this down. Just know an author’s second book is always much harder to write than his first.”

An editor rejected a submitted book. I asked, “Can you tell me what’s wrong with it?” The answer, “It has no salt.”

When another editor turned down a book of mine, I asked her if there was any part of it that was good. Her reply, “You can keep the title.”

Another editor’s rejection: “If I published this it would hurt your reputation.”

This is from an editor regarding a book we had been working on for a year: “You did everything I asked you to do but it’s no good.”

Another editor: “I have to turn it down. I love it, but my boss thinks no kid will ever read it.”

A Goodreads review: “I was forced to read this book in school and it’s the most boring book I ever read. Don’t, don’t, don’t ever read it!!!”

Sometimes when you are a writer it’s best to be like a turtle: wear a hard shell and keep up a slow but steady walk forward.

January 30, 2024

I’m Considered One of Those Writers

Readers often have favorite authors or genres, in part because those writers or types of books provide the same kind of reading satisfaction in a regular fashion. They will often return to the same author. Nothing wrong with that. By and large, you know what you will be getting if you pick up a Dr. Seuss book, or one by John Le Carré. Indeed, I know someone (an adult) who endlessly reads and rereads the Harry Potter books.

But what of those writers who write many different kinds of books?

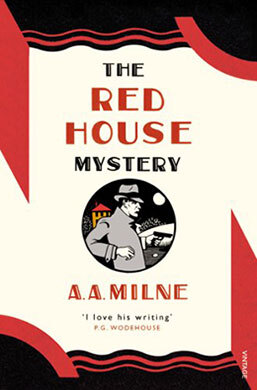

As an occasional reader of mystery books, I was intrigued when I recently read an article in the New York Times, about a 1940’s detective novel called The Red House Mystery that was being recommended as a forgotten classic. What attracted me to the book was the author, A.A. Milne. He was the guy who wrote the Winnie-the-Pooh books.

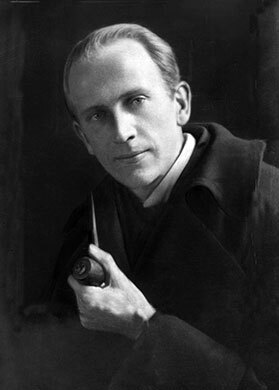

A.A. Milne, Shadowland, Emil Otto Hoppé, 1922 (public domain)

What was he doing writing a mystery?

I read the book. Turns out it is one of those “cozy” British 1920s mysteries set among upper-class folks (no known source of income) in a fancy house somewhere in England, not far from London. It features an amateur detective and his dumb sidekick, with a very elaborate (and rather unbelievable) murder deception. It was fairly well written, but all-in-all not very interesting.

But why did Milne write such a book?

It seems that Alan Alexander Milne (1882–1956) was a prolific writer for the stage (eighteen of them) as well as screenplays. He also wrote humorous pieces for the periodical Punch, as well as other novels, and essays. Active in both world wars, he was also considered a good cricket player, and had a team called “Authors Eleven,” with a group of fellow authors that included Barrie (Peter Pan), Conan Doyle (Sherlock Holmes), and P.G. Wodehouse (Jeeves), the squad sounding rather like a Monty Python sketch.

Milne has been quoted as saying “The only excuse which I have yet discovered for writing anything is that I want to write it.”

It has also been noted that Milne came to resent the enormous fame and success that the Pooh books brought him, at the expense of the neglect of his other work. That in the face of the claim that Milne and his wife exploited their child Christopher Robin for the money the Pooh books brought it.

But what interested me here is the spectacular range of Milne’s writing. How do readers respond to the writer of different kinds of work?

This caught me because I’m considered one of those writers. There is my True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle (historical fiction), The Poppy Books (animal stories), The Most Important Thing (realistic short stories), School of the Dead (ghost story). And so on.

Sometimes readers complain that I am not writing the kind of book they like, but another kind. I recall a Goodreads review by a reader who picked up City of Orphans, thinking it was a dystopian fantasy. Then, to her disappointment, she discovered it was realistic historical fiction. “It was not what I expected,” she wrote and therefore gave it a very negative review.

At the moment I am trying to decide which of four ideas I wish to pursue as my next novel. Each one is very different from the other.

All I know is that if I follow Milne’s thought: “The only excuse which I have yet discovered for writing anything is that I want to write it,” I will write my best book.

So be it.

January 23, 2024

The Art of Fixing a Shadow

Photography has long fascinated me. When I visit art museums it is the photography section to which I inevitably go. I have, moreover, spent a good deal of time reading and learning about it. At one point, when living in Providence, Rhode Island, I took photography classes at the Rhode Island School of Design, at a time before digital photography became the norm.

And more. I set up a darkroom in the basement of my house and worked with film. I had an enlarger, and pans of chemicals to develop the images I took, along with a book of careful detailed records of how I developed individual pictures. There, shrouded in red light (which did not affect the photographic process) I spent many a night creating black and white images. There was a mystery and adventure about it all which I loved. Anyone who has watched an image blossom up in a pan of developer fluid will know what I mean.

[I wish I could share one of my photographs, but they are all stored away — I’m not even sure where.]

At the time I was immersed in all of this I wrote three books, which, I believe, were greatly influenced by my engagement with images.

The first book was City of Light, City of Dark, a graphic novel (created with Brian Floca). While creating a fantasy adventure, the great emphasis was on the visual depiction of story, environment, and character. When I first suggested such a book to my editor, Richard Jackson, he had no idea about what I wanted to do. Only when I sent him a copy of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, did he understand what I had in mind.

The second book influenced by photography (in a reverse way) was “Who Was That Masked Many Anyway?” This is a novel that is one hundred percent dialogue, without any description of place, with not one “he said,” or “she said.” It is a homage to my youthful days of endlessly listening to children’s radio adventure stories.

Two books: one with nothing but visualization, the other without any visualization.

The third book, Seer of Shadows, is a ghost story, set in the 19th Century. It tells a tale about a boy who is apprenticed to a photographer who makes fake “spirit pictures,” images that professed to show ghosts of departed family. (Such images were enormously popular in the 1870s, a time when most people didn’t understand how photographs were made.)

In my story, the boy discovers that his photographs really do show images of the departed, and the subsequent adventure that follows.

As part of the story, there are descriptions of the way film photography was done, based, in part, on my darkroom work.

[After my father — who had dabbled in photography — passed away, I found a roll of film in his home, which he had never processed. I took it to my darkroom and brought up the images. One such image was of my twin sister (aged two?) standing next to my mother. It had to have been taken fifty years before.

My mother was wearing a fur coat, which, to my astonishment, I instantly recalled. More than that: the moment I saw it, I recalled what that fur coat smelled like. The scent-memory of that coat lasted only seconds, after which I never could retrieve it.]

I had to give up the darkroom when I learned how toxic were the photo chemicals I was using. Added to that I also realized the basement in which I was working was coated with asbestos. Not — to put it mildly — a safe environment.

As I learned more about photography I became an admirer of the work of Cartier-Bresson. One particular image he made fascinated me. Because of copyright restrictions, I can’t show it here. But if you Google Cartier-Bresson Girl On The Steps, you will see his picture of a girl (in Greece) running between two buildings. Capturing as it does, a fleeting image of a girl between places, it remains, for me, a personification of what Children’s Literature is all about, catching a moment in a young person’s life.

William Henry Fox Talbot, (1800–1877) who in 1835 became one of the inventors of photography referred to his process as “The Art of fixing a shadow.”

Those words always also seemed a perfect description of the writing of novels.

January 16, 2024

Now Winter Has Come

This morning, in Denver, it was minus eight degrees. Surely, winter. So I reminded myself of the last lines of the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem Ode to the West Wind, “If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?”.

But impatient in our tiny two-room town hut (as I call it) we brighten things up with flowers.

There is the late blooming Christmas Cactus. [Schlumberger, from Brazil.]

A pot of African Violets. [Streptocarpus, from East Africa.]

Lily of the Incas [Alstroemeria, from Peru.]

And finally, yet to bloom, Paperwhites [Narcissus papyraceus, from the Mediterranean region.]

To coin a phrase, this bud is for you.

January 9, 2024

Not All Fiction is Fiction

It’s a new year so here is an old story.

For most of the year, I live in a log house 8900 feet up in the Rocky Mountains, right on the edge of Routt National Forest. It’s in the unincorporated township of Clark, north Routt County, a county larger than the state of Rhode Island. It’s thirty miles north of Steamboat Springs, six miles from the Wyoming border.

Avi’s cabin in the Rocky Mountains [photo: Avi]

Avi’s cabin in the Rocky Mountains [photo: Avi] It’s a beautiful place surrounded by forest, high peaks, and deep valleys, one of which allows me to look down for sixty-five miles.

Rocky Mountains surrounding Avi’s cabin [photo: Avi]

Rocky Mountains surrounding Avi’s cabin [photo: Avi] It’s a beautiful place surrounded by forest, high peaks, and deep valleys, one of which allows me to look down for sixty-five miles.

It was in 1889 that Hannah Emily Clark opened a post office on her homestead. She named the post office CLARK, thereby giving the new town a name. Back then the post office served a population of seventy-five persons. These days — as far as I can tell — the rural township has a population of about five hundred and forty.

Winters can be very snowy (thirty-four feet last year) and cold, which is why locals have given the area the nickname, “The Clarktic Circle.” That’s why I spend the winter months in Denver. It’s not much fun to drive sixty miles on snowy roads to get food. As I write this it is seventeen degrees in Clark, fifty-five in Denver.

There is no postal delivery to my house. If I wish to mail a letter or pick one up, I must drive sixteen miles. These days the post office is in a building known as the Clark General Store. The store functions as the center of the town, and it’s there, more than anywhere, I meet my neighbors.

The Clark General Store [photo: Avi]

The Clark General Store [photo: Avi] The small store has different departments. It has a tiny grocery store. A smaller liquor store — by state law with its’ own cash register. A deli — where you can have lunch. I can also pick up a copy of the local daily newspaper — the Steamboat Pilot — a free newspaper. Benches and tables are there so I can have coffee and meet up with friends.

The post office, which has a service counter, is mostly taken up by postal boxes. It’s all run by one person, and you do not just pick up or drop off your mail, you chat with the postmaster and exchange news with her or other folks there.

The Clark General Store [photo: Avi]

The Clark General Store [photo: Avi]  Mailboxes at the Clark Post Office [photo: Avi]

Mailboxes at the Clark Post Office [photo: Avi] My favorite part of the store is the wall of books located in the post office area. Regularly stocked, and restocked, by Steamboat’s public library, these books — mostly new, and in fine condition — are offered free to the public. There you can find all kinds of books, mostly fiction, but also nonfiction. A couple of shelves of children’s books are there, too. I’ve been told that some fifty or, so books are taken each week, which suggests an elevated level of readership in Clark to go along with its altitude.

I’ve taken a few myself.

Bookshelves at the Clark General Store [photo: Avi]

Bookshelves at the Clark General Store [photo: Avi] A few years back, friend and colleague Brian Floca, came to my Clark home to scout out the scene before doing illustrations for our book, Old Wolf. Without saying so, the tale is set about my land.

Part of the story takes place in that General Store. Thus, one of the illustrations Brian did is of the post office. In the illustration, he inserted the portrait of a man. The man he depicted was Richard Jackson, the late great editor, and the editor of that book, not that he ever was in Clark.

Looking out from the postal desk is Sophie Blackall, one of Brian’s studio mates, and two-time winner of the Caldecott award.

Sometimes the illustrations in books have their own tales to tell.

Which is to say, not all fiction is fiction.

illustration © copyright Brian Floca, from Old Wolf,

illustration © copyright Brian Floca, from Old Wolf, written by Avi, published by Atheneum, 2015

Avi's Blog

- Avi's profile

- 1703 followers