Avi's Blog, page 8

May 21, 2024

“Not Lost in a Book”

Slate, an online magazine devoted to political affairs, culture, and current trends, recently had an article about middle school reading and publishing that I think is required reading for any of us interested in children’s books. The title of the article is “Not lost in a book.”

The writer (Dan Kois) reports that the sale of middle grade books is radically down. Kids in third and fourth grade have stopped their fun reading, a trend pushed by the pandemic. Screen time is an issue, but the way reading happens in schools these days is a greater problem. It’s the new curriculum. “In elementary school,” to quote the article, “you read, you take a quiz, you get the points. You do a reading log, and you have to read so many minutes a day. It’s really taken a lot of the joy out of reading.”

All this is radically muting the love of free deep reading at a crucial stage in child development.

The result? “More and more publishers are looking for light, funny-stories-with-pictures that can help uncertain readers make the leap from picture books to big-kid books.”

In other words, literature is considered suspect. The literary book is not what publishers want because, quite simply, they are not selling. Part of the reason they are not selling is because they are under attack.

Never forget that publishing is a for profit business.

It doesn’t help that publishers have given over much of their marketing to social media.

I can speak from personal experience about all this. I had two books in the pipeline, only to be turned away because “kids won’t care about the subject.” And, “No one wants historical fiction. Too risky.”

I have heard this from several editors.

Let me hasten to say I did sell one of those books, but it was a struggle. And I do have a track record that helps.

But if you are considering writing a thoughtful, experience-immersing story, you are going to have a difficult time publishing, selling, and getting kids to read it.

Hard times in the world of reading.

May 14, 2024

The Book That Influenced Me

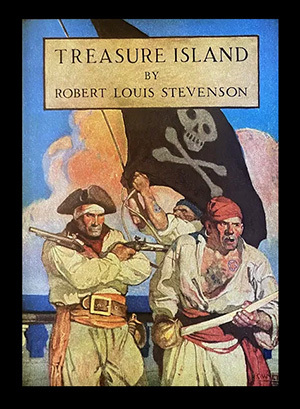

If I had to pick one book—from my early reading—the one that most influenced the way I think about books and the writing of books, it would be Treasure Island, written by Robert Louis Stevenson. Though he had already established himself as a gifted writer of short stories and essays, Treasure Island, astonishingly, was his first novel.

He would write, “On a chill September morning, by the cheek of a brisk fire, and the rain drumming on the window, I began The Sea Cook, for that was the original title. I have begun (and finished) a number of other books. But I cannot remember having sat down to one of them with more complacency.”

Complacent! Beyond all else, this is a wonderfully throbbing novel, with more energy and life on every page than some books have with 300 pages.

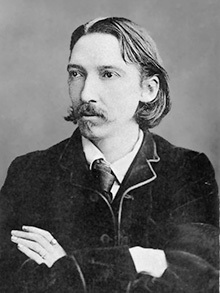

Robert Louis Stevenson [Wikipedia]

Robert Louis Stevenson [Wikipedia]Building on his familiarity with earlier nineteenth-century writers of adventure stories — Kingston, Ballantyne, Marryat, and Cooper — Stevenson meant this as a story for boys and wrote Treasure Island in particular for his stepson Lloyd Osbourne.

Famously, the idea of the book began with a drawing of a map — a map of what would be the island with the treasure [see the end of this article]. Any edition of the book should have that map replicated. There have been numerous attempts to locate the “real,” island, and has been claimed from Puerto Rico to California to Scotland. I have little doubt that it is fictitious.

As for the tale itself, there is extraordinary intensity in the telling, for the most part in the voice of young Jim Hawkins. That, I have little doubt, is part of its attraction for youthful readers.

And the characters that people the story, oh the characters! Beyond all else, there is Long John Silver, the leader of the pirates, who swings from soothing kindness to murderous betrayer with nary a slip of light between. This oscillation, in fact, reminds me of another of Stevenson’s great works, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, written a few years later.

“Absconding with the treasure,” N.C. Wyeth illustration for Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson

“Absconding with the treasure,” N.C. Wyeth illustration for Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson It is Silver, one-legged, peg-legged Silver (and his constant companion, the parrot Captain Flint) who pushes the story forward even as he pushes his money-mad crew forward. Silver is filled with such life, such charm, such rich language that I think we are relieved (as I suspect Stevenson was) that at the end of the story he escapes to live out his (fictional) life.

But there is also Ben Gunn (and his deep love of cheese), Old Pew with his blindness, and Billy Bones with his songs. I can talk about them as if they were old friends.

The good guys, the squire and the doctor, are not nearly as interesting characters as the bad guys. Truth be told they have no more rightful claim to the treasure than the pirates.

Indeed the story is full of moral ambiguity.

It is also, to be sure, a violent story with much death and mayhem. Only five of the original crew return to England. That said, all the fighting and murders have an element of fantasy about them, as if to say, if you are going to tell a tale of pirates you just have to do this — but don’t worry — it’s just a story.

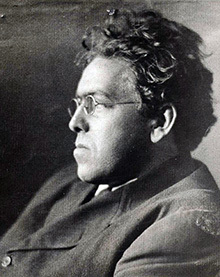

N.C. Wyeth [Wikipedia]

N.C. Wyeth [Wikipedia]And if you can get hold of the book with the 1911 full-color illustrations by N.C. Wyeth, they match the genius of the text. For many years I had a copy of Wyeth’s image of Blind Pew over my writing desk, a reminder to work hard and find my own blind way as I wrote.

As for Stevenson, never a healthy person, he died very young, leaving behind a legacy of a wonderful person, much loved and admired.

Henry James, the great English writer, who was his good friend, wrote this to Stevenson’s widow. “For myself, how shall I tell you how much power and shabbier the whole world seems [with Stevenson’s death]. He lighted up one whole side of the globe and was himself a whole province of one’s imagination.”

I can say as much for Treasure Island.

Map from Treasure Island, written by Robert Louis Stevenson [Wikimedia Commons]

Map from Treasure Island, written by Robert Louis Stevenson [Wikimedia Commons]

May 7, 2024

This is Where I Came In

I have long believed stories — narratives — are one of the basic forms of communication. Narratives are one of the ways we make sense of the world. It’s how we create logic out of chaos. No surprise then that I have always been fascinated by different forms of narrative and have come to believe that the way one tells a story is a key part of that story.

I believe that jokes are a form of narrative, as is gossip. The Bible tells a story. So does the daily newscast. By way of contrast, one disturbing aspect of nightmares is that they have no logical narrative: they can be troubling (even frightening) because they are disjointed.

As a writer, I am not committed to any particular form of narrative. When I sit down to compose a story, I generally begin with the question, “How am I going to write this story?” It can take me awhile to work that out, and I am open to any form.

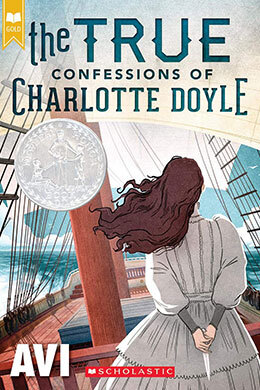

Consider two of my books, The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle, and Nothing but the Truth. Published one year after the other, one is a straightforward plotted tale, the other a plot created by interconnected documents.

I have written a graphic novel (City of Light, City of Dark) and a novel which is all dialogue — no descriptive text at all — Who Was That Masked Man Anyway?

I created the highly successful serial story venture, Breakfast Serials, which ran stories chapter by chapter in newspapers. I once held a class at New York University on “the narrative structure of daily newspaper strips.”

I’ve composed very short stories (Things That Sometimes Happen) and very long novels, (Beyond the Western Sea). That’s in contrast to picture books with less than a thousand words.

The three Crispin books (long novels) are written in Iambic pentameter. The Button War (a novella) has language that is brief and terse.

The Poppy books — written over a twenty-five-year period — and not written in the order of the full story arc, can now be read as one continually flowing tale. It’s a case of a disjointed tale becoming one story over a long time of creation.

One of the oddest forms of narrative experience I have experienced happened when I was a kid, going to the movies.

In those days (the 1940s) we just went to the movies. I can’t recall ever checking to see when the film began as I do today. In any case, when we went to the movies then, it was not just to see one film, but several. There was an A movie and a B movie. Often, there was a newsreel between the films. If it was a kid’s showing, there were perhaps several cartoons and a chapter of an ongoing serial.

But normally, when I went to these movies — because we didn’t seem to care when they started — we sat down in the theatre in the middle of one of the long films.

We sat through the entire offering until we came back to the part of the story when we first sat down. At that point, one of us said, “This is where we came in.”

We left the theatre.

That meant we reconstructed the whole story of one of those films by putting together (in our thoughts) the last half and then the first half — backward!

Indeed, have you not sat down with a friend or relative, and in response to the question, “How are you?” got the same old story you have heard a million times?

In your head (you are too polite to say it) comes the refrain, “This is where I came in.”

Life is, in fact, a story.

What’s your story?

April 30, 2024

A Love Story

It was in 1994. I was living in Providence, Rhode Island.

In the spring of that year, I was invited to accept an award for my book Nothing but the Truth in Phoenix, Arizona. At the same time, I received an invitation to visit four schools in Denver, Colorado. With my East-Coast mentality, I thought the cities were close together, not the almost 600 miles that were the distance between them.

I accepted the invitation.

Shortly thereafter, I received another call, this time from the manager of a Denver bookstore, a children’s bookstore. Called The Bookies, it was one of the largest children’s bookstores in the country. I was asked, since I was coming to Denver schools, would I do a signing at the store?

Sure, I said.

An agreement was made, and I was told they would pick me up at the airport. I’d do the signing and then I’d be delivered to the school’s designated hotel.

All agreed.

Some five months later I went to Phoenix, accepted the award, and flew up to Denver. But when I got to the airport there was no one to pick me up. After waiting a long while, I called the bookstore and asked about the ride.

Seems the bookstore had a brand new manager and, after much apologizing, she explained she knew nothing about picking me up. “Please wait. I’ll come get you.”

I waited.

After some time a battered Jeep Cherokee pulled up to the curb and a skinny, pretty lady wearing a kilt jumped out. With renewed apologies, I was taken to the bookstore. During the ride, I learned that this woman had only just become the manager of the bookstore and had been told very little about my visit.

As it turned out nothing had been done to promote the signing. The only kids in the bookstore were two of this lady’s children. The eldest, a twelve-year-old girl, was shelving books. The six-year-old boy was only interested in something he was collecting. “Pods,” I think they were called.

The fact of the matter was no one showed up for the signing. All the same, I was stuck at the store for a couple of hours. There was nothing to do but talk to that lady.

We talked a lot.

Now I am not a believer in “love at first sight,” but by the time I left that bookstore, I had fallen in love with that lady. Linda was her name.

The next day I went to the first school. As I spoke to the assembled kids, I noticed that Linda was there, standing at the back of the room. Seems she had kids there.

When I got back to my hotel, I called the bookstore, asked for Linda, and invited her out for dinner the next day.

That we did, and we talked a great deal more. After dinner, she took me back to my hotel. “Could we go somewhere and talk some more?” I asked.

“I have to go home,” she said.

I went to my room.

But down in the lobby, Linda had a change of mind. “I need to speak to one of your guests,” she said.

“What’s his last name?”

Linda had a sudden realization. “I only know his first name.” At that point, she grabbed the guest register from the startled clerk and searched down the list of names until she found my whole name and called me.

“Let’s talk some more.”

That we did. A lot.

Reader, I married her.

Best book signing I ever went to.

April 23, 2024

Ready to Move Forward

After a month or so of dithering — trying out this notion, that notion — I’ve committed myself to the book I intend to write next. Indeed, I’ve already rewritten it twenty times. I’m trying to define my voice. I am trying to define my main character. Trying to grasp a sense of what I’ll be writing. Indeed, trying to shape (in my head) the plot. All standard for me.

I’m ready to move forward. Sort of.

You might think with some eighty-seven publications on my resume, this should be a stroll in the park. You might think I have had so much experience — good experience — that I should be able to slide right along.

Not so.

I can think of many reasons for my unease.

The world of publishing — at least as I have known it — has changed a great deal.

I’m being told that middle school books are having trouble in the market. One reason offered: the way books are sold has changed drastically. I have heard one insider say, “Publishing no longer knows how to sell books. They have been flattened by the steamroller that is Amazon.”

The old ways of marketing — in person — have given way to social media, with authors being asked to lead the way — and do the work. That requires whole new skills, which I’m not sure I have. Or want to have.

I know of a sixteen-year-old girl who has been hired to track down “influencers” as a means to sell books.

A long-time publisher recently wrote to me: “People [in publishing] are totally on edge! There’s an environment where there is no margin for error and all the talk is of optimization and streamlining, which are all terrible things for creativity and occupations that need relationships, connection, and time.”

Another business insider (not a writer) with years of publishing experience tells me that “The editors are all overworked. They have no time for ……”

This has given rise to caution about taking risks — one of the things that used to give publishers the capacity to unearth and develop new talent.

Indeed, the whole process of publishing — at least in children’s book publishing — has slowed down, evidence of that caution.

And I do not doubt that the recent political attacks on books, schools, and libraries (including teachers and librarians) have made these buyers of books for institutions very cautious, perhaps timid.

Then too, as elsewhere in society, the pandemic caused all kinds of shifts, ways of working, and ways of being. Writing and publishing are not immune. One result: There doesn’t seem to be (looking in from the outside), the bonding collegiality in publishing houses that there once was.

Beyond all that, there is the simple truth that it is always hard — for me anyway — to start a new book.

It’s a little like walking along the edge of the Grand Canyon, knowing I have to get across to the other side. I have to find a trail and then follow it to the bottom, then up the other side.

Or I can simply ignore all of the above—maybe these are just excuses, and I need to just settle down and write the best book I can. Maybe it’s that simple.

Wish me well and luck. Writers need it.

April 16, 2024

Censorship

I’ve tried to recall if my reading was ever censored when I was a kid. In elementary school, I don’t think I ever read an assigned novel. Book reports were required so I must have read something beyond the basal readers we used in class. No idea what.

At a fairly early age, I was given a public library card and was free to walk to the nearby local library. In one sense there was censorship because — if I was there without a parent — I was restricted to the children’s section. I have no memory of wanting to go to any other section. It’s possible I did, but I have no recollection of being turned away.

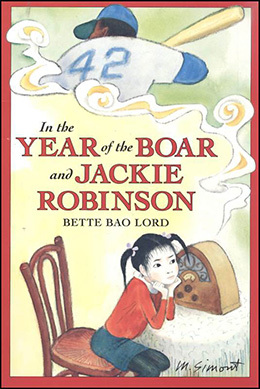

I lived in a house of books, not the least medical books, since my father was a doctor. I don’t recall sneaking looks in those books. That said, in The Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson — the author, Bette Bao Lord, who was a classmate and good friend of my sister, recounts (in the book) how she and my sister snuck into my father’s office to look at naughty images.

I lived in a house of books, not the least medical books, since my father was a doctor. I don’t recall sneaking looks in those books. That said, in The Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson — the author, Bette Bao Lord, who was a classmate and good friend of my sister, recounts (in the book) how she and my sister snuck into my father’s office to look at naughty images.

My mother, who was in charge of our reading, did have one restriction regarding what I read, the horror comics of the 1950s. I was a voracious comic book reader, but there were such comics as Horror, Tales from the Crypt, Zombies, and American Vampires. (I like that last title!) My mother had a curious restriction regarding those comic books: I could not bring them inside the house, but I could and did read them on the front stoop. I’m not sure this is censorship. What I recall from these comics was brilliant color and ghoulish creatures. Still, though I did read them I was not (nor am I now) given to acts of violence or the digging up of dead bodies.

In upper elementary school The Amboy Dukes, a 1947 “novel of youth and crime in Brooklyn,” written by Irving Schuman, was reputed to be full of sex. In my school, it was passed around by the boys but only to read certain parts, not the novel as a whole.

Once again I must have read some of it, but have no memory of such, though as I sat down to write this I did recall the title — if not the author.

AbeBooks (an online used book broker) is offering an early paperback edition of The Amboy Dukes for fifteen dollars.

“Condition: Very Good. Avon #169, 1948. First Avon printing. A Very Good copy. Rubs to the corners and spine tips. Some paint chips to the spine edges. Mild dusting to the rear cover. Lightly tanned pages. Cover art by Ann Cantor.”

But a first edition of the Doubleday hardback will cost you $450.00.

Let it be said that as an adolescent I was a big reader. A diary I kept during my senior high school year has long lists of books I was reading — having nothing to do with schoolwork. Impressive authors are noted, Shakespeare, and Milton, among many classic and modern writers. By that time, I had already made up my mind to be a writer. That said, the depth of my 17-year-old intellect may be measured by my favorite phrase in the book. In its entirety, I wrote:

Read Plato. Not bad.

I once visited a class of sixth graders. I asked them what they were reading beyond that required reading. Someone called out, “Stephen King.”

“Does anyone else read him?” I asked.

Half the class raised their hands.

The teacher was astonished. She had no idea.

By way of contrast, many years ago — while on a book tour — I met a woman who proudly informed me that whenever her young daughter told her there was a movie she wished to see, the woman took it upon herself to go see the film first to make sure “it was okay.”

“You must see a lot of movies,” I said.

“I have to,” she said. “It’s my responsibility to keep her from the bad ones.”

But of course, she was seeing all the “bad ones.”

Ah, it must be rough to be a censor.

While it is true that many people who object to a book have never read it (getting the titles from lists) a good number do read those forbidden books.

I think two questions should be required:

Did you read the book?Did you enjoy it?I suspect they often do.

April 9, 2024

Details, Details

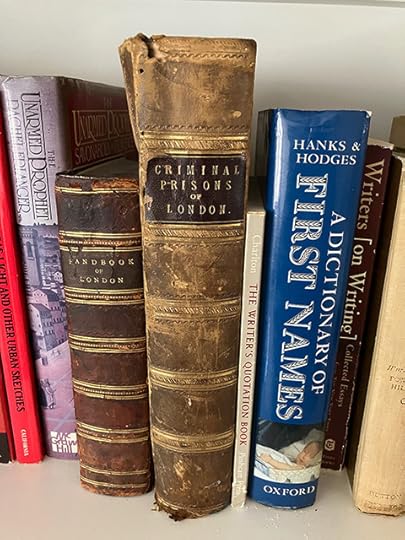

I have a fondness for old books. The oldest on my shelf was published in 1850 and has the title, Handbook of London, Past and Present. I believe I acquired it when writing Traitor’s Gate. It was wonderfully useful when trying to track the streets and places in London at that time. The other very old book I have on my shelves is Henry Mayhew’s Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of Prison Life. It is dated MDCCCLXII (1862). This volume is splendidly illustrated. Here again, I believe I used it while researching Traitor’s Gate. There are scenes in this old book that provide extraordinary details of life in an English prison. Those details became an important part of my book.

Thus, information such as the “Daily Diet list” at the House of Detention, Clerkenwell: On Sundays, Males and Females there were fed “4 ounces of meat, 2 ounces of gruel and 16 ounces of bread.” Furthermore, “All prisoners are allowed to be visited by their friends, from 12 till 2 daily, Sunday’s excepted.”

The subtext of this information is that many working people only had Sundays off, which meant they could make no prison visits to family or friends on that day.

As I am sure you can imagine, this kind of detail is invaluable when writing about such times and places.

When I hold such old books, I have to wonder who else held them, and under what circumstances. And how did they even read them? Or use them? The typeface is extraordinarily small (by today’s standards). Even more bewildering is to contemplate how the type was set and proofread.

The old leather bindings have a singular musty smell of which I’m fond. Though the paper is old, it is in better condition than many recently published paperback books. I suspect it has a high rag content.

A recently acquired book that was published in 1927 (for a current project) has on the back of the title page, a note: “Five hundred copies of this volume have been printed from type and the type distributed.” In other words, only 500 copies ever existed. I now have one of them.

In this context, I have several dictionaries, such as one of medieval words, and a reprint of Grose’s (1785) A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. (“Vulgar” here, means slang.) Thus a “filching mort” is “a woman thief.” Somewhere I have an edition of Roget’s original (1851) Thesaurus.

When doing research for The Secret Sisters — in which Ida goes to a 1925 high school, I got a hold of some textbooks from that time.

Why else would I now have a 1923 Latin textbook?

Yes, such old books provide details, but most of all they enable me to give life to my characters, situations, and even places. My readers tell me they love these details.

The truth is, so do I.

April 2, 2024

Ah, A I

Without asking my permission Grammarly — the spelling and grammar checker — has proofread my writing since 2016. At least that’s their claim. They inform me that I’ve used 23,896,330 words during this time. Not sure I believe that. They further instructed me that my primary writing problem is commas. That, I believe. In particular, they say I am inept at putting in commas after introductory clauses. Also — they say — I’m messy with using commas in compound sentences. But they are happy to teach me proper usage.

Did you know (according to Grammarly) that commas are used in the following ways?

Separating items in a list of three or more Connecting two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction Setting apart non-restrictive relative clauses Setting apart nonessential appositives Setting apart introductory phrases Setting apart interrupters and parenthetical elements Setting apart question tags Setting apart names in direct address Separating parts of a date Separating parts of a location, like a city and its country Separating multiple coordinating adjectives Separating quotations and attributive tagsIn truth, I could have not written those rules. I’ll try to do better. But I’d feel a lot better if, when using A I, they would insert a V between those letters.

March 26, 2024

My Library Life

Montague Branch, Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History. This library closed in 1962. [Copyright Brooklyn Public Library, used with permission.]

Montague Branch, Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History. This library closed in 1962. [Copyright Brooklyn Public Library, used with permission.] When I was a kid, living in Brooklyn, NY, a Friday visit to the local public library was part of our family routine. I have no memory of when I had my first library card. But at some point, I had one and was allowed to walk to the library on my own. Which I did, often. To be sure, I was only allowed to use the “Children’s Section,” walled in by low bookcases off to one side of the main floor.

At the same time, we kids were encouraged to have individual libraries. There was always a gift book at Christmas and birthdays, which helped to build it.

It must have been known I liked books because I have one — dated December 23, 1947 — my tenth birthday — as a gift. Inscribed on the title page, it reads,

“To Edward from his friends: Susan/Biff/John/Ann Elizabeth”

Each name is written by a different hand. I still have that book.

I have no memory of a public school library, so I am not even sure there was one. We only used basil readers, though at some point book reports were due. I must have used my local public library.

Memorial Union Library, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin

Memorial Union Library, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin[photo: James Steakley, WIkipedia CC BY-SA 3.0]

At the University of Wisconsin (Madison) where I went (a double major, History and Theatre) there was a large academic library. Not only did I use it to study, but I worked there as a student clerk. It was in the university’s annual student literary publication that I was published for the first time — a one-act play.

Patience, the lion statue in front of the New York Public Library, designed by Edward Clark Potter, and sculpted by The Piccirilli Brothers, dedicated in 1911. Fortitude, his companion statue, is to the right, outside of this photograph. [photo credit: Spiroview Inc, Adobe Stock]

Patience, the lion statue in front of the New York Public Library, designed by Edward Clark Potter, and sculpted by The Piccirilli Brothers, dedicated in 1911. Fortitude, his companion statue, is to the right, outside of this photograph. [photo credit: Spiroview Inc, Adobe Stock] In the 1960s, in NYC, my wife and I — she a modern dancer, I a would-be playwright — tried to cobble a life together with a variety of jobs in the time-honored way of young artists—doing this and that. Then she became ill. It fell to me to find regular employment. In search of work, I wandered into the main branch of the NY Public Library the one with those lions at the main entrance, known as “Patience” and “Fortitude.”

It turned out the Theatre Collection — one of the library’s divisions — needed a clerk. Moreover, I learned that they would soon be moving into new quarters at the brand-new Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. With expanded facilities, they would be hiring librarians.

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, entrance from Lincoln Center Plaza [photo credit: Kosboot, Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0]

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, entrance from Lincoln Center Plaza [photo credit: Kosboot, Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0] I got the job, and within a week had enrolled at Columbia University Library School. Recall that I was a playwright (writing mostly bad plays), so this was a lovely fit. I would work at the Theatre Collection for ten years until my low salary and growing family pushed for change.

I became humanities librarian, and instructor in library skills for all new liberal arts students at what was then known as Trenton State College. I held that job for some twenty years, working there when my first book, Things That Sometimes Happen was published in 1970. I wrote my first historical novel, Captain Grey, during a forced vacation (or sorts) when the faculty went on strike. The setting for Wolf Rider is that campus. I lost a friend because he became convinced that the villain of the piece was based on him — not so. Beyond all else colleagues and bosses were always supportive of my writing.

During this time I was also haunting flea markets in search of old children’s books, building up a library of some three thousand historically interesting volumes. At a later date, I would give them all to the University of Connecticut, which had just created a children’s book collection.

Having published a fair number of books I decided to leave library work and see if I could support myself and family with my writing. I decided to try for a year, promising myself that I only needed to make as much as my librarian’s salary. A low bar, to be sure. With that achieved I left being a working librarian.

By then I was writing more historical fiction and my library knowledge helped create a new way of working. I knew how to do research, and whenever I chose a new book topic, I gathered up a small library on the subject.

Books from books if you will, until I amassed a library of some five thousand books. I was the only librarian. And patron.

As the kids grew and left home, we moved to a much smaller place. I gave (not sold) most of those five thousand books to used bookstores. I had plenty left.

I kept writing and built small library collections for specific research projects. Between Inter-library Loan and used bookstores (via the Internet) I can pretty much get any book I need.

Recently I was trying to decide among three prospective projects, each very different from the others. Trying to make up my mind I collected three libraries, one for each subject.

I chose one. But I can always turn to the others if I have the need. I already have a library for each project.

Finally, when in Denver and taking my daily walk, I plan my route from “Little Library” to “Little Library.”

Ever the librarian. I just write some of the books.

Little Free Library, Denver Colorado [photo credit: Avi]

Little Free Library, Denver Colorado [photo credit: Avi]

March 19, 2024

Visiting Chickens

After three years of not going to schools — Covid — my visits have resumed.

Yesterday, when I pulled into the parking lot of Denver’s Park Hill Elementary School, I was immediately greeted by the clucking of chickens. A quick investigation informed me that the school not only had a community garden, but also a chicken coop on its grounds. The school building, originally built in 1901, is adorned with high, unlabeled bas-relief portraits of people, though I think I recognized Jefferson.

As I walked through the main entrance I was greeted by a sign saying, “Welcome to the home of the Panthers,” along with an image of a ferocious beast, an unlikely icon for a K–5 school.

(A brief chat with the principal informed me he had no idea who assigned such a logo. Almost always, these logos are ferocious male beasts. My favorite: Our Lady of Mercy Tigers.)

As I made my way to the front office to get my visitor’s badge, the school passed my first test of a good school; lots of bold student art was posted everywhere (rather than artistic classics, such as by Rembrandt, or Winslow Homer), recognizing kids for what they are, young people who love color and uninhibited shapes.

Then too, there was a sense of amenable chaos, a feeling of energy and enthusiasm, which promised engaged kids. Show me a school with neat, clean (and empty) hallways, and I know I’m in an uptight, controlling environment.

I was ushered into the auditorium where a bunch of girls were rehearsing a play, a retelling of an ancient Greek legend about how spiders came to be. Much arm waving and eye-rolling represented all kinds of emotion.

When kids filed in, any number of them were clutching a wide variety of my books. The feeling I sensed was one of excitement and interest as many eyes studied me with curiosity.

After a short introduction by an enthusiastic teacher — which happily did not sound like an obituary — I introduced myself and showed a short PowerPoint, which showed images of my home, my family, pictures of my elementary school, my fourth-grade class, and high school, the scathing comments of my English teacher on a paper as to my bad writing skills, my inept high school soccer team. Then briefly, images of my writing process, rewritten pages, outlines, and the like.

Then, for the remaining time, which is most of the time, I take questions, making a point of going from girl to boy, while ranging over the whole room to make sure I reach the various grade levels who have assembled.

The questions asked are the reasonable ones I am most often asked, “Where do you get your ideas?” “How long does it take you to write a book?” “If you weren’t a writer what would you do?”

Then there are some questions that pertain to specific books kids have read; “How did you get the character names in True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle?” Or “In The Secret School, how did you get the idea as to how Ida drives a car?”

Sometimes these questions are hard for me to answer because whereas a kid has just read a particular book, it’s one I wrote twenty years ago, or more. It’s a reminder that one of the joys of literature is that for the reader a new book is always new.

Then there are the quirky questions, “What do you think of adjectives?” “If you could be a character in one of your books, which one would it be?”

Throughout, my job is to respond to a question as if I have never heard it before and then give a reply that speaks to that particular student, indicating I recognize him or her as an individual.

My intention is to suggest that I am an ordinary person, someone who had to work hard to acquire writing skills. If there is any one theme, it is the centrality of reading as the key to a writer’s life and learning.

And what do I get out of this event? It’s not money. This was a neighborhood school, which I met pro bono.

First, it is exhilarating to be in a happy school, full of youthful energy. In today’s hard world, it’s full of much-needed hope. It’s also deeply reassuring to see that kids are reading books I have written.

Most of all, I regain a connection with my readers, a reminder that I am not writing for editors, publishers, reviewers, or Goodreads evaluators: I am writing for young people.

When I go back to my desk and resume writing, I see their faces as I try to create books that young people enjoy reading. It’s that simple. It’s that hard. And I love what I do even as I love my readers.

Avi's Blog

- Avi's profile

- 1703 followers