Theodora Goss's Blog, page 2

December 3, 2024

Absolving Myself

There is a scene I have always liked in movies. It is when a priest administers absolution. He makes a particular gesture that means “I absolve you of your guilt, your sin, your transgression. You are forgiven. Go and do better.” There is always a sense of relief afterward, a sense that now the protagonist can start over. A sense of renaissance, new birth.

I was thinking about this recently because it seemed to me that after a period of intense productivity in which I published a novel every year, the last of them in 2019, I had a period of about five years in which I was much less productive. I wrote short stories, poems, and essays, and I even published some collections, but no novel. And of course I wondered what was wrong with me, what happened to derail the plans I had made for myself, which of course included writing more novels.

And then I looked back, and realized. The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl was published in 2019. At that point, I knew that I needed a break — my schedule for the second and third Athena Club books had been so tight that I was exhausted. But I had plans. I remember talking about them at the World Science Fiction Convention that year — it was in Dublin. And then, in January 2020, Covid happened. That semester, we started on campus and ended on Zoom. In the fall, I taught remotely. The next spring, I taught hybrid classes. The fall after, I was granted a Professional Development Leave of Absence to develop a curriculum that focused on creativity and innovation in writing pedagogy. The following spring, the spring of 2022, I taught on a Fulbright Fellowship in Budapest. The Covid pandemic was ending, so I started teaching on Zoom and ended on campus. That was also the year Russia invaded Ukraine, the year of refugees coming across the border. Right after the Fulbright, I taught a summer semester in the College of General Studies London program. The following year, I taught a full CGS curriculum for the first time. Which brings us to the fall of 2023.

In the fall of 2023, I applied for a permanent position at CGS. In the spring of 2024 I went through the interview process and got the teaching position I had applied for, which made me so glad and grateful. At the same time, I was going through the process of getting ultrasounds and biopsies for a lump on my neck that the doctors eventually decided might be cancerous. At the end of spring semester, I had surgery. Fortunately, there was no cancer, just some odd-looking but completely benign cells. That summer I taught in London. And then, in the fall, I went to Budapest and opened up the manuscript of the novel I had planned so long ago, which I had barely started before Covid hit. And now I’m working on it.

So there you go. Why wasn’t I as productive as I had planned to be in the past five years? Because in those five years, I have not had a single semester that has been the same, in which I’ve been able to say, “It’s fine, I know what I’m doing.” I’ve been working and learning, and I’ve loved most of it, except the Covid and the surgery. I really do love being a teacher, and it’s a joy to work with my students. But the truth is that writing is work, hard work, work that takes time. I love doing it, and I do it for the love of putting words on a page, but it’s not something I can do in bits of time between doing other things. Poetry, yes. A novel, no. That takes focus and concentration.

So I’m officially absolving myself. I’m making that priestly — in this case priestessly — gesture that means I am forgiven. And if you need absolution, if the last few years have not been as productive for you as you would have liked and you’re feeling guilty, then consider yourself absolved as well. You don’t even have to confess anything, and you don’t need to be particularly contrite. Believe me, I know you feel badly enough about it already. If you’re anything like me, you carry a load of guilt for all the things you did not do, or did not do well enough, as well as for the dishes in the sink and the fact that you haven’t vacuumed for a while.

Let’s start fresh, like pieces of laundry hanging on the line. Let’s figure out what we want to do now, and not worry about the past. It has flown away like a flock of swans, and we are left with a field of possibility that we can fill with more swans, or dancing princesses, or a carnival. If you’ve already started working on something, go you! If not, get out a fresh notebook, or a blank canvas, or whatever you’re going to start on. Figure out what you want to do, and go do it.

Of course, if you’re still in the middle of a great muddle, just hang in there and get through it. But I’m grateful that for the first time since my last novel was published, my life feels relatively stable. Of course, there are crazy things going on all over the world — our political situation is fraught, the climate is out of whack, and it’s entirely possible that humanity will destroy itself within the next few years. But in the meantime, I’m going to be writing.

(The image is Cloister Lilies by Marie Spartali Stillman.)

October 22, 2024

Writing a Poem

I was thinking about what is hardest to write, and I ranked the various things I write from easiest to hardest: essays, stories, poems.

In terms of word count, poems are definitely the hardest and most time-consuming. Yesterday, I spent an entire day working on a poem, one I had already spent several days working on. It just would not come right. When a poem does not come right, it feels as though you’ve been bitten by an insect, and the bite is itching and itching. You keep scratching, but it does not bring relief. Every time you think the itching has stopped, it starts up again. And then, when the poem does come right, it feels as though you’ve finally discovered Calamine lotion, and it’s actually working. There’s a sense, not of joy or fulfillment, but of relief. Finally, you think. The damn thing is done. At that point, you’re angry with the poem for even existing. What began with a sense of delight has become a source of annoyance. You tell the poem, if it weren’t for you taking up so much time, I could be writing a novel and becoming a famous novelist, or a great novelist, or a rich novelist — or all three, like Charles Dickens. But no, here I am working and working on a poem that probably ten people will read . . .

Poetry sucks.

On the other hand, I must love it or I would not write it. And I do. Poetry is the only thing I write that feels as though it could achieve a kind of artistic perfection. A completed vision. I often tell students, only poetry is capable of being perfect, and only one poem has ever actually been perfect (John Keats’s “Ode to Autumn”), so there is no point in trying to write a perfect story or a perfect novel. It’s just not going to happen.

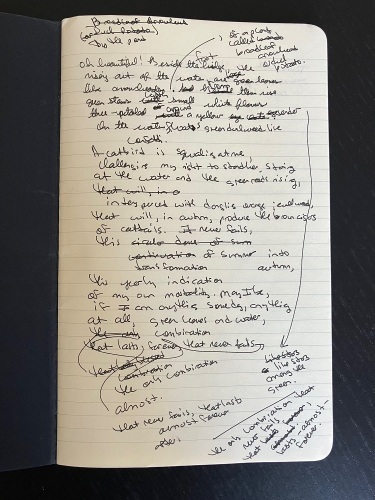

Would you like to see what my poetic process looks like? If not, you can stop reading now . . . But if you want to see, I’ll show you. Recently, I wrote a poem that annoyed me very much. I wrote the first draft back in September, with a pen in the notebook I carry around in my purse, standing on the footbridge described in the poem and looking at the leaves growing up from the water below. I didn’t know what the leaves were, so I did an internet search on my cell phone, and they turned out to be broadleaf arrowhead leaves. Then, I wrote a poem about them. It looked like this:

Then I did not do anything for a while. I was in Boston and there was just so much I needed to accomplish before I could come to Budapest. But of course I brought the notebook with me. Finally, after dealing with a plumbing problem in Budapest (a broken pipe in the apartment above mine), I had time to write. I typed up the poem, revising as I did so. At that point it looked like this:

The Broadleaf Arrowhead (or Duck Potato)

Oh beautiful! Beside the footbridge,

rising out of the water, are the large green leaves

like arrowheads, of a plant called broadleaf arrowhead

or duck potato. From among them rise

green stems with clusters of white flowers,

three-petaled around a yellow center, as though stars

were scattered among the green. And on the water floats

green duckweed like confetti. A catbird

is squawking at me, challenging my right to stand here,

staring at the water and the green reeds,

interspersed with dangling orange jewelweed,

of bulrushes rising behind the arrowheads,

with their own stems, taller and a darker green,

that will, in autumn, produce brown cigars of cattails.

It never fails, the yearly transformation

of summer into autumn, that annual reminder

of my own mortality. May I be,

if I am anything someday, anything at all,

green leaves and water, the only combination

that never fails, that lasts almost forever.

And I felt that terrible itching. I had words, even some of the right words, but they weren’t in the right order. They didn’t have the right rhythm. They hadn’t found their proper places yet, and I was missing some words — I was sure I was missing some words. I would need to learn more about the broadleaf arrowhead. So I did some research — yes, I did research for a poem. Honestly, this poem could come with a bibliography! At some point, I was going to include information about how the broadleaf arrowhead was also called the wapato, which is a word the native Chinook used to mean “potato” when speaking with French and English traders. It’s not a Chinook word, but a jargon word they used because the traders could not speak proper Chinook. (I learned that “jargon” is a linguistic term meaning an “occupation-specific language.”) That went into the poem and came out of the poem because it just didn’t fit. It made the poem sound like a middle school history report.

When I tried to describe the broadleaf arrowhead itself, I needed other words I didn’t know, words like “scape,” “raceme,” “inflorescence.” I needed to know that “whorl” is a technical term in botany. I put things in, took things out, moved things around. It all became rather complicated. Somewhere along the way, I realized that the poem was mostly in a sort of rough iambic pentameter, and I thought, why don’t I commit to the meter? At that point, I almost gave up and deleted the whole thing. This was about a week after I had initially typed it, and I had returned to it over and over, as I had time, obsessively trying to get it right.

Finally, it looked right to me, and I posted it. And then I thought, wait, there are just a few things I could fix . . . So I fixed them. Somewhere in that process, I realized the second stanza had eight lines and the first stanza had fifteen lines, which didn’t feel right. So I added a line to the first stanza. Eight and sixteen just felt better . . . It’s such a strange process, mostly of intuition. But at the same time, I was constructing something, and it needed to be structurally right. It needed to have sixteen lines, then eight lines, and to be in a kind of iambic pentameter (if you don’t look too closely).

And now the poem looks like this:

The Broadleaf Arrowhead (or Duck-Potato)

Oh beautiful! Beside the footbridge, growing

out of the water, are the large green leaves

of a plant called broadleaf arrowhead or duck-potato.

Among them, from the water, rise green stems

called scapes, along which grow its small white flowers,

each with three petals around the yellow stamens,

arranged in whorls along a central raceme

and clustered in a pattern called inflorescence,

like stars against the green. Beneath them float

lenticular leaves of duckweed, like confetti.

An angry catbird is squawking from its perch

among the bulrushes, as though to challenge

my presence in this tangle of summer foliage —

the arrowheads, the dangling orange jewelweed,

the rushes whose stalks, rising from tall green blades,

will, in autumn, produce brown cigars of cattails.

They remind me of the annual transformation

of summer into autumn, and of course,

inevitably, because I am only human,

my own mortality. May I become,

someday, if I am anything, anything at all,

this, right here, despite the annoying catbird —

green leaves and water, the only combination

that never fails, that lasts almost forever.

I don’t know if it’s any good, but it’s finally what it wanted to be, or I wanted it to be, or Erato, the muse of lyric poetry, wanted it to be. I don’t know who wanted the poem to be this way, but it finally feels finished. It finally feels like Calamine lotion . . .

So that’s it, that’s my poetic process. I honestly don’t know why I write poetry, except that it does something good to my brain — my brain feels right afterward. It feels as though it’s been used to do what it was designed for. That won’t make me a rich, famous writer, and it may never make me a great one, but it probably makes me a better one. I hope.

September 22, 2024

A Lament for the Stores

Once upon a time, there were stores.

From my apartment in Boston, I could walk to two grocery stores. Granted, they were a Whole Foods and a Trader Joe’s, so it felt like living in a posher, more expensive area than I would have liked. The Whole Foods had actually replaced a health food store that had replaced a Market Basket. For anyone who doesn’t live in Boston, Market Basket is a local chain, founded by a local family, that serves ordinary middle-class communities. The health food store did not last long, because the community could not afford its more expensive offerings. The Whole Foods lasted a few years, but about a year after Whole Foods was acquired by Amazon, it left. That spot was empty for two years.

While the Whole Foods was still there, that strip also had a hardware store where I could buy all the things I needed to hang pictures (hammers, nails, those little bent things that the nails go into), lamps, ladders, cleaning supplies, unfinished wooden shelves, garden equipment, plants, and in December, Christmas trees. The landlord who owned that strip evicted the hardware store and built a metal awning, hoping the space would be filled with restaurants. So far it has been filled with one takeout place and one bubble tea shop. The rest of the space stands empty.

In the other direction, there used to be a Walgreens and a Gap, as well as a gourmet food store. The Walgreens went away first, to be replaced by a bank. Now there are four different banks in that area. The only drug store left is a CVS, which used to be a good CVS until the management brought in two checkout machines and reduced the number of clerks. At that point, the store started having a problem with shoplifting. So it put much of the merchandise behind plastic panels that have to be opened by a clerk. Did I mention there are not enough clerks? I’ve waited half a hour for a clerk so I can buy toothpaste. The Gap went away, as did the gourmet food store. Some of those places now stand empty, although the Gap was replaced by a daycare center, which is surely a good use of the space.

Near the university, the same sort of thing has happened. Once, in Kenmore Square, Boston University had a big, beautiful Barnes & Noble. It was three floors, filled with the most wonderful books, and on the first floor it had a café. I used to go there to meet graduate students and colleagues. Across the square was a Starbucks. The Starbucks left first, I don’t know why because it was quite heavily used by students. The building with the Barnes and Noble in it was sold, and now it’s some sort of office building advertising retail space on the first floor. No one has moved into it, so it’s just empty storefront. The new building next to it, which replaced a rather pretty although delapidated early 20th century structure, is the most boring building I have ever seen, made of prefabricated material that went up quickly. It has a sign on top that says WHOOP, so it must be the headquarters of the “wearable technology company” (I got that from the Internet) of that name. Honestly, I think they left off the final S — the building deserves a big sign that says WHOOPS. It also has empty storefront on the first level, with big fancy windows that look like dead eyes. The post office where I used to pick up packages and the corner convenience store where I used to buy chocolate no longer exist.

Kenmore square still has a bar and a few restaurants, but I don’t go there anymore. Why would I? There is nowhere to meet, sit down, have a cup of coffee. Nowhere to browse, nowhere to buy anything.

So many of the stores have gone. I lament the hardware store especially. Now, if I need the sort of thing that can only be bought in a hardware store, I must take the metro to Target or order from Amazon. I order from Amazon a lot more than I used to, not because I want to, but because I don’t have time to wait in CVS until a clerk can get away from watching the checkout machines to liberate a jar of face cream from its plastic prison.

It’s not a consistent phenomenon, of course, but it seems as though we’re losing the stores. I’m lamenting this for several reasons. First, I generally don’t want to buy something online. I want to see it, to make sure I like it, that it fits or that the proportions work. When I order something online, there’s a chance that, although I used measuring tape to make sure the lamp would be the right size, it is not, somehow, the right size after all. It doesn’t fit, and then I need to go through the further step of returning it. Second, I want to walk to the store. I want to walk and browse and get out of my apartment, see other people, listen to random conversations. I want to pick out my own apples and peaches.

I don’t know if this is a particularly American phenomenon, but in both Budapest and London, I was surrounded by stores. Budapest is the best, in that way — within a fifteen minute walk of my apartment there are about five different grocery stores. There are cafés, places to buy ice cream, a place to buy flavored cheesecake in little glass jars, a hummus bar, restaurants of all sorts, shops for both new and used clothing, stationery stores, book stores that sell Hungarian and German and English books, stores for ceramic flowers . . . And of course there is the Great Market Hall, where you can buy vegetables and meat and cheese from stalls. In some ways, except for the height of the buildings, Budapest is more like New York than Boston. In London last summer, I was in quite a posh area near Sloan Square, and many of the stores were expensive boutiques. Still, I could walk to three grocery stores and there was a Waterstones nearby. There were hardware stores and stationery stores in the general neighborhood.

The one good thing about my Boston neighborhood is that we do have an independent bookstore. It recently expanded, and it seems to be doing very well. But I lament the passing of the other stores. Whether they were chains like Gap or small boutiques, they gave us somewhere to go. I’m particularly sad that Kenmore Square has become a kind of corporate desert. The students deserve better. They chose to come to an urban university, and they deserve what a city should give everyone — a lively street culture. Cities need life and soul. Bostonians will remember the old Harvard Square, before it too became a kind of corporate desert. I still go there sometimes to buy office supplies from Bob Slate, but otherwise, why bother?

I don’t have any words of wisdom here — I’m just sad to see the city change, and I think it’s a bigger issue than one city, one neighborhood. I’m always glad when the trend reverses itself — after two years, the empty Whole Foods was replaced by an H Mart that seems to be doing a lively business. But if I’m living in a city, I want to live in a neighborhood with a grocery store, a pharmacy, and a hardware store that I can walk to. In a really ideal location, I also want a café and a bookstore. That does seem to be the minimum for good urban living?

I’m very lucky to live where I live and work where I work. But I miss the stores . . .

(The image is The Shop Girl by James Tissot.)

September 15, 2024

Writing My Stories

In the last few months, I’ve written three stories.

Two were stories I was asked to write. One is a retelling of “Sleeping Beauty” from the ogress’s perspective. (You don’t remember an ogress in “Sleeping Beauty”? Read the Charles Perrault version, originally published in 1697. There’s an ogress . . .) Another is the secret history of Mina Harker, whom you may remember from Dracula. The fairy tale retelling is for an anthology; the Dracula retelling is for my next short story collection, coming out in 2025 from Tachyon Publications. The third story, which I finished just yesterday, is one I wrote for myself, although of course I’ll try to publish it somewhere. It comes from an incident I saw in Budapest — an older woman who, to my surprise, stopped by the planter in front of my apartment building, pulled up a plant, put it in a plastic bag, and walked away. She stole a plant! I stood and stared, astonished. And of course it gave me the idea for a story.

People sometimes ask me how I get ideas for stories, or whether I have trouble coming up with ideas, and I say no — the ideas are the easy part. There are ideas quite literally everywhere. They fall out of the air like rain. A woman steals flowers, I read a poem or hear a song, I read a book and think That’s a great plot but I would do it differently, I visit a beautiful place and it gives me a story. There are stories everywhere I go. The hard part is writing them down, and the even harder part is finding time — that is literally the hardest part for me, because I so often have very little time. And the most difficult thing about writing, for me, is prioritizing my writing time.

I don’t know if you have this problem, but it’s very difficult for me to prioritize what I would most like to do over my obligations to other people. I’m very lucky to have a job that I love, which is teaching. But I have obligations to many other people — my students, my department, my university. And then there are obligations to family and friends, which are important as well. Sometimes, writing feels like an obligation only to myself — if I don’t write, it will affect only me, whereas if I don’t grade essays or write letters of recommendation or participate on the assessment committee, it will affect other people. It’s easier to let myself down than to let other people down.

And yet, it seems to me that there is another perspective: if I don’t write them, I let the stories down. And I let down anyone who may want to read those stories, who might find some benefit from them, even if it’s the ability to get away from our difficult world for a while. And I do know this about myself as a writer — I have a power to take people away from this world and transport them somewhere else. That is one thing I know I can do. Beyond that, there is something more difficult to describe — I let down wherever those stories came from. I’m not arrogant enough to think those stories came solely from me. I don’t just think them up. Parts of them come from me, certainly. But when I’m writing, it feels as though the story is being told through me, in collaboration with me. The source of stories is pouring through me like a river, and I am both channeling it and riding it on some sort of writing kayak. It’s as though I’ve been given a job by the university, which is to teach students — and I hope I do that job well, but I’ve also been given a job by the universe, which is to tell whatever stories are out there to be told.

I suppose thinking about it this way may also help with the other problem, when you’re a writer, of feeling as though there are already so many stories out there. Walk into a bookstore or library — you will be overwhelmed (or at least I am). And then there are all the shows on Netflix, all the videos on YouTube. There are already so many stories, most of them more spectacular than mine. I mean, how could what I write compete with a Netflix series?

And yet. You never know what will be important. There was that guy, the one you would probably have avoided if you had seen him in a café, because he was, admit it, kind of weird. And he painted these weird paintings which you probably wouldn’t have bought, because no one was buying them. There he was, in the small town of Arles, and almost no one was paying attention to him, and he was painting and painting and painting. And now one of his paintings is on my umbrella, which is as close as I will ever get to owning a Van Gogh. So you never know.

All you can do, as a writer, is try to let go of your ego as much as possible, and write the stories that are given to you, as best you can. Like painting and acting and dance, it’s one of the great humbling professions. You will fail again and again and again, because failure is the essence of trying to create anything. And whenever you walk into a bookstore or library, you can see all the great writers, right there on the shelves — you can see that Virginia Woolf is already there, and F. Scott Fitzgerald is already there, and you’re not going to be as great as they are, because no writer can be another writer. You’re going to have to figure out how to be great, or even pretty good, or maybe even not very good, in your own way.

This is, perhaps, why AI will in the end not be very helpful for writers of anything more complicated than undergraduate essays (and not even in those, I would argue). You need to have your own failures before you can have your own successes. AI isn’t telling the stories the universe gave you to tell. It’s telling bits and pieces of stories that other writers told, patched together like the Patchwork Girl of Oz. Using AI to create a story makes you, not a writer, but an editor, which is a different job altogether. I’m sure there are people who will disagree with me, but for me, writing is in the direct engagement with the words on the page. It’s in the intersection between what comes to me from somewhere outside myself, and the skill and thought I put into capturing it, structuring it. It’s dancing with the universe, not with a machine.

So, what will I do with my flower thief story? Well, I have a few ideas. Right now, all three stories still need some revisions, so next week I will be a reviser rather than a writer. But my goal for this year, especially for the next few months, is to create space and time for writing. After all, I have an obligation to the universe. And the rest of it — whether my stories are published, whether they find an audience, whether they eventually appear on umbrellas (all right, here I’m kidding — a little), all of that is ultimately up to the Fates, who always have their own agenda.

(The image is Old Woman Watering Flowers by Gerard Dou.)

September 8, 2024

Collecting Scars

I think life is a process of collecting scars.

Mine are inconsequential, all things considered. The oldest ones are the marks from immunizations: smallpox on one arm, tuberculosis on the other. If you were born in the United States, you won’t have these. But when I was a child, in socialist Hungary, we were still being immunized against Victorian-era diseases. So I have a round scar on one arm the size of a five-forint piece, a smaller round scar on the other. There is the small round scar near one eye from having chicken pox, and the small straight scar near the other eye from a rowdy-boys-during-gym accident in high school. After I got that one, I was wheeled through the school in a wheelchair with blood flowing down my face. I felt quite injured and fancy! When my mother looked at it, she said, “Oh, that’s nothing. Wounds like that always bleed a lot.” Then she put a few butterfly steri-strips over it, and that was that.

Then there are my two appendectomy scars from graduate school. I suppose they mark where the video camera and surgical tools went in. I can barely see them now. And then there is the scar from the thyroid lobectomy in May. That’s the largest and most prominent, of course. I still don’t know how I feel about it. Perhaps I will feel differently when the internal scar tissue is not so palpable. Right now, four months after the surgery, it still feels like I have a rubber eraser in my neck. I’m still using scar gel and SPF 50, still doing scar massage, the way they demonstrate in the YouTube videos. I feel very lucky that there have only been two serious problems with my health so far — appendicitis and recurring nodules on my thyroid — and that they are very common problems to have. All in all, I’ve spent very little time in hospitals.

Nevertheless, I think life is a process of collecting scars. They don’t go away, not fully — they are like marks on the map of your body, showing where you’ve been, what you’ve experienced. Time writes your history on your skin, just as you might write it in a journal. Except, of course, that time’s journal is public. You can see the scar on my neck, although it’s slowly fading. And when you see it, you might ask yourself (if you’re too polite to ask me), What happened there?

But I was thinking too of the scars that are not written on our skin, the scars that are inside, that affect our hearts and minds. Life is a process of being wounded, healing, but then feeling the scar left behind — because I think there is always a scar left behind. From each hurt, each loss, each failure. And then it’s a process of waiting as we heal, of trying to help the healing process. The first medicine for my surgical scar was oxycodone. For heartbreak, the first medicine might be hours of watching Netflix, which would have a similarly numbing effect. Instead of applying scar gel, you might apply ice cream where it hurts. Or music. Or long walks. Or, of course, therapy.

I suppose it depends on the depth of the wound, the extent of the scar. For some wounds, the process of healing is long, and the resulting scar can limit your mobility, your flexibility — this is as true for mental and emotional scars as physical ones. I don’t know what the process of scar massage might feel like for these internal scars. I’m not a therapist. But there must be one — there must be a way of dealing with them so they hurt more in the short term, but less in the long term. Hopefully, if I’m diligent about the massage part of my therapy, the rubber eraser in my neck will eventually go away, and I won’t feel it each time I swallow.

So I guess I don’t really have any wisdom here, because scars aren’t exactly beautiful, and saying that everyone becomes scarred is not an optimistic statement. The scars fade, but never completely. But I’m not trying to say something wise or optimistic. Rather, I’m trying to say something about how I’m experiencing life right now, which is as a relentless march of time that marks you as it passes. And yet, and yet, we also write on paper, and that is as valid as what time writes on our bodies.

Perhaps it is the way we respond to how time scars us. Perhaps the marks we make on paper are the way we take time’s power into our own hands, make our marks against time. We say, “You may scar my body, but look — these words will outlast me.” Whether on clay or papyrus or parchment, we have been doing this since writing began. And now here I am, doing it on a computer screen, writing, “I think life is a process of collecting scars.” And perhaps, just perhaps, if these words are shared and copied and remembered, they may outlast my physical body. Or other words of mine may be the ones that last, who knows? And so, I continue to collect scars and make my marks on the computer screen, as I am doing now.

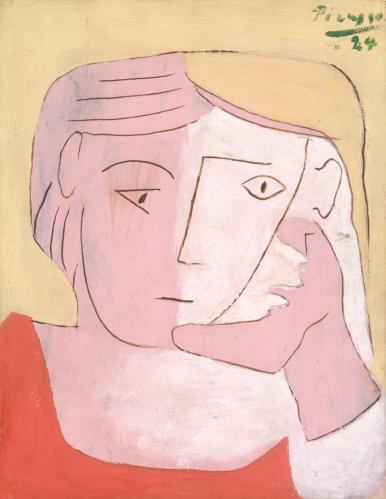

(The image is Head of a Woman by Pablo Picasso.)

May 25, 2024

The Process of Healing

I was sent home from the hospital with three bottles of pills: oxycodone, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen. They were white pills in orange plastic bottles, very much hospitals pills: uncoated, difficult to swallow. I only took a few of them. I quickly realized that the oxycodone was much too strong for me. I only used it in the first few days, when I couldn’t sleep. The ibuprofen was also too strong and gave me nausea. After the first week, I went back to my ordinary Tylenol and Advil.

That first week, I mostly slept and ate and slept. By the second week, I could get back to work, and I had to — I needed to finish grading for the semester. Just after my grades were in, I received the final biopsy result. This was the real biopsy, not the fine needle biopsy that had told us the thyroid nodule was “suspicious for malignancy.” Now, post-surgery, they would actually be able to diagnose what had been happening in my neck. The result was: benign. There was no malignancy. I had what they called an “oncocytic follicular adenoma,” which used to be called a Hürthle cell adenoma.

Of course I did some research. One of the funniest parts of this experience has been that I always try to do my research, so when my endocrinologist or surgeon said to me, “According to the most recent studies,” I could say, “Yes, I read those studies,” and I had — in JAMA or on the website of the National Institutes of Heath or wherever. This is what happens when you’re treating a rhetoric professor who teaches research techniques for a living (and whose parents are doctors).

(Medical procedures are highly comical, in a dark comedy sort of way. My surgery only took a few hours, so I went in on a Thursday morning and went home that same afternoon. When I got home and looked in a mirror, I realized that I had purple lines on my neck. There was a thin purple line going down my neck, and then one thin purple line across the middle, and a thick purple line below. There was also an arrow drawn on the left side of my neck. The thin purple lines must have been some sort of surgical marker — I looked those up too, and apparently they’re called SkinMarker. You can buy them on Amazon. They look like the white board markers I use in my classrooms. The surgeon must have used them to plan the incision, sort of the way an artist starts by drawing a series of lines showing relative proportions. The arrow must have been drawn on to indicate which side of my thyroid to remove. The thick purple line was surgical glue covering the incision itself. It was not a dark purple, more like a violet that eventually faded to lilac — a happy color that reminded me of a muppet. It made me laugh to see the little arrow on my neck, while it lasted.) So, as I said, I did my research.

The best and clearest description of what I had comes, unsurprisingly, from Wikipedia, which says that “Hürthle cell neoplasm is a rare tumor of the thyroid” that occurs mostly in women. “When benign, it is called a Hürthle cell adenoma, and when malignant it is called a Hürthle cell carcinoma. Hürthle cell adenoma is characterized by a mass of benign Hürthle cells.” Of course I wanted to know who Hürthle was, even though the medical profession is moving away from naming conditions after people. Wikipedia says that Karl Hürthle (1860-1945) “was a German physiologist and histologist” who received his degree from the University of Tübingen and became famous for his contributions in the field of haemodynamics. While I understand why we might not want to keep the old names of diseases, it sounds much more impressive to say that I had a Hürthle cell adenoma than an oncocytic follicular adenoma, perhaps because of the German name, especially with an umlaut. An umlaut makes everything seem much more serious.

The process of healing is really a process, and it’s psychological as much as it is physical. I had been expecting this diagnosis, simply because I had gone into the surgery knowing the possibility of cancer was about 15-30%, which meant the possibility of no cancer was 70-85%. That’s a pretty large possibility. And I had talked to the surgeon about how I would feel if that were the case. Would I feel as though the surgery had been unnecessary? As though a part of my body had been removed for no reason? The problem is that, according to an article from Oncologist called “Follicular Adenoma and Carcinoma of the Thyroid Gland” (which is the sort of article I would expect my students to cite — no Wikipedia for them!), “A major limitation of fine needle aspiration biopsy . . . is the inability to distinguish a follicular adenoma from a follicular carcinoma.” And, as Wikipedia puts it, “Typically [an adenoma] is removed because it is not easy to predict whether it will transform into the malignant counterpart of Hürthle cell carcinoma, which is a subtype of follicular thyroid cancer.” Basically, without surgery, there is no way to tell whether you’re looking at an adenoma or a carcinoma, and you can’t tell for sure what will happen to an adenoma in the future. They are very unlikely to turn cancerous. But unlikely is not the same as “never happens.”

That did not keep me from bursting into angry tears when I saw the diagnosis, nor having to spend a week working though the psychological confusion of it. Would it have been better if we had found a malignancy? Of course not. Would it have been better if there had been no need for surgery — if we could have known it was a benign adenoma in the first place? Yeah, sure. Should I have taken the other option I was given by the endocrinologist and waited until the fall, then done another ultrasound and fine needle biopsy? I asked the surgeon if it would have made any difference, if we would have gotten any different information then. “No,” he told me. “The FNB would have come back either ‘suspicious’ or possibly ‘indeterminate.’ It would never have come back ‘normal.'” If it would have come back “suspicious” again, I would definitely have chosen surgery, so we would have ended up in the same place. If it would have come back “indeterminate,” we would all have worried that the second fine needle biopsy had missed something.

Here is the takeaway, the hashtag quotation: Life is a series of decisions you make with insufficient information. You can put that on Goodreads.

(Another humorous part of this, for me, is that these categories were created by a team at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland in order to standardize diagnosis, so they are called Bethesda I through VI. My diagnosis, “suspicious,” was Bethesda V. The funny part of it is, when I was a little girl, my mother used to work at the NIH, and I used to go there after school whenever for some reason we did not have a babysitter. So I would play in the halls, and sometimes, since this was the olden days before the current strict protocols, I could even visit the rabbits and mice. My elementary school artwork hung in a laboratory in NIH Building 10.)

(Another humorous part was when I took back all the pills I had not taken to the hospital pharmacy for disposal. “You really don’t want these?” the pharmacist said, as though he could not understand why I would give back free medicine. “I really don’t,” I said, handing over the orange plastic bottles. They were basically still full. Hospital medicine is foul stuff.)

The final part of this process, for now, was a blood test. It came back normal — the right side of my thyroid seems to be humming along, merrily pumping out all the thyroid hormones I need. It doesn’t seem to miss the left side at all.

Of course, I’m still healing. The purple surgical glue has mostly come off, but a strip of it is still sticking to me, as though it does not want to leave my neck. The incision site is a bit hard and swollen. There’s work going on in there — my cells repairing things. It’s a reconstruction site. The scar looks very good — it’s thin, and unless you’re standing close to me, you might not even notice it. It will fade even more over time. Someday, I will have wrinkles there and it will be invisible. For now, I need to treat it with silicone gel and keep it out of direct sunlight, so I’ll be wearing a bandage over it for a while.

The psychological part is harder. I’ve been incredibly lucky with my health. So far I’ve had an appendix and half my thyroid out. Those are the only serious medical problems I’ve had. But this experience has reminded me how fragile and miraculous bodies are. They’ve reminded me that I have a limited time on this earth, and that I’d better make the most of it. Some days that’s a depressing thought, some days an invigorating one.

It is, at any rate, a reminder that I need to do my work, the work that is in me to do, while I can.

(The image is Catherine La Rose by Richard Emil Miller.)

April 29, 2024

Me and My Thyroid

My thyroid and I got along very well for a long time. We had a good relationship — I lived my life, and it provided me with the hormones I needed. There was that incident about twenty years ago, when suddenly I noticed a bump on my thyroid. It was about the size of a quarter, and filled with something — it felt like half of a water balloon. I went to an endocrinologist, who gave me a long talk about thyroid cancer that was, I think, more for the resident who was helping him than for me. He put a needle into the water balloon to get some fluid to test, and the water balloon deflated. The test came back negative. It had been nothing — a harmless cyst.

So when I felt a bump on my thyroid again, shortly after Christmas, I had some context for it. I knew approximately what it could be. I managed to get an appointment at the clinic where my primary care provider works — it took waiting for two weeks, and I would only be seeing a nurse practitioner. Apparently all the actual doctors were busy. The receptionist was also busy talking to her friend while I tried to make an appointment. That was the start of my journey in making appointments, and every appointment system was as bad as that first one. I have a theory that the most difficult part of healthcare in American is making an appointment with anyone anywhere. The second most difficult part is, of course, the billing system. I have tried to explain to European friends about “co-pays.” They stare at me blankly.

The nurse practitioner ordered a bunch of tests, all of which came back normal. She also requested an ultrasound, for which I had to go to Boston Medical Center. The ultrasound results came back. I had some nodes on my thyroid. They looked normal. No follow-up recommended. But I still had a bump on my throat. My mother, who happens to be a doctor, said, “You need to have it biopsied.” So I wrote to the nurse practitioner, I need to have it biopsied. She gave me a referral to an endocrinologist. I called to make an appointment.

It took a month and repeated phone calls to get an appointment. There was the phone call during which I was given an appointment in six months; the phone call during which I was told that no, that was just for patients coming back for checkups, and someone would call me back; the phone call during which I was told I needed to talk to Ashley; the one where Ashley was not available; the one in which I was told there had been a cancellation and I could come in tomorrow, and I had to explain that I was a professor and would be in the middle of teaching class; the phone call with Ashley; the follow-up phone call with Ashley. And then I had an appointment, a month from the day I talked to Ashley. (You can’t call Ashley or anyone else to make an appointment. You have to call the central number, click all the right buttons through the recorded message, wait to music you have not heard since the 1990s, and then talk to someone who tells you that someone else will call you back.)

Between the time that I got the appointment and the appointment itself, the bump on my throat disappeared. That happens sometimes. It doesn’t mean there wasn’t an underlying problem. Anyway, I already had an appointment with an endocrinologist, so I went — just to make sure the bump had, indeed, been nothing to worry about.

The endocrinologist did another ultrasound herself. Apparently, the radiologist who read the first ultrasound had miscounted the number of nodules. There were in fact more than four, and most of them looked harmless, except two on the left side. “There’s a lot of vascularization there,” she said, holding a cold wand to my throat. I’m very lucky that I know what vascularization is. I mean, I have a PhD in English literature. It’s not a medical doctorate, but it is a doctorate in words — in what they mean, how they’re put together. It’s a doctorate in, when I don’t understand something, looking it up. At every point, dealing with the American medical system, I wondered how someone without an advanced degree in understanding language, someone who might not even be fluent in English, would deal with it. “We really should biopsy those specific nodules,” she said. So she did, with a long, thin needle.

The biopsy for the larger nodule came back “suspicious for malignancy.” Suspicious, not definite. Even if it’s definite, the problem with this kind of biopsy (an FNB, or fine needle biopsy) is that it’s never really definite. An FNB can only give you a percentage certainty. The official percentage for “suspicious” is a 15-30% chance of malignancy. That’s a very big chance that it’s not, in fact, malignant. But there’s only one way to be sure. “I recommend surgery,” said the endocrinologist. “I’ll have someone call you for an appointment with the surgeon.” So there I was in the appointment system again, but this time within Endocrinology. The Ashley of this system was called Blaise. Once you can speak to the Ashleys and Blaises of the world, everything goes smoothly. The trick is identifying who they are and then getting to them.

The surgeon and his colleague, a specialist in thyroid issues, did another ultrasound. Everything looked fine, they told me, other than those two nodules. My lymph nodes looked fine. The other side of my thyroid looked fine–the nodules there were harmless. But the side of my thyroid with the suspicious nodule, that side should go. They recommended a thyroid lobectomy, which means that the surgeon takes out half the thyroid. It’s serious surgery, but one with an excellent success rate. Even if the patient has thyroid cancer, the long-term survival rate is 99%. The one thing I remember from that first episode, twenty years ago, is the endocrinologist telling me, telling the resident, if you’re going to have cancer, thyroid cancer is the best kind to have.

The difficulty was, I didn’t know what I had. There was a 15-30% chance of malignancy, and a 70-85% chance that it wasn’t. That was the information I had, and I would have to make a decision based just on that. The FNB doesn’t give you certainty — it’s just a small number of cells pulled up through a needle. The only certainty comes after the surgery, when they do a full, real, official biopsy on the whole nodule. Then you know for sure. But by then, the decision has already been made.

I talked to the endocrinologist again. She said I could choose surgery, or I could put off the decision until the fall. We could do another FNB, although it would not necessarily give us more information. “What would you do if it were you?” I asked her. Surgery, she replied. I talked to the surgeon again. During my first conversation with him, I had almost laughed several times. It had been almost like being in class at medical school. Perhaps because he knew that my mother was a doctor, and that I was a university professor, he had explained everything very thoroughly, in all its complex uncertainty. I had wondered, again, what my experience with the American medical system would be like if I did not understand Latinate terminology. But knowing big words doesn’t help you make a decision in a situation like this. “What would you do if it were you?” I asked him over the phone. Surgery, he replied.

In the end, I decided based on two things. The first was something the surgeon said. “If everything on that side of your thyroid was clear and easy to observe,” he said, “I would be fine with waiting and doing another ultrasound. We could see if the nodule changed over time. But that side of your thyroid looks weird.” It was the word “weird” that struck me. You don’t really want an endocrine surgeon saying your thyroid looks weird. The other thing was that I have lived in this body a long time. I trust it. I know when it’s trying to tell me something. First, it sent me a bump. The bump did not go away until I had already made an appointment with an endocrinologist. I think my body was trying to get my attention. Since then, I’ve been able to feel, not always but sometimes, that there’s something wrong on that side of my throat. I can feel a sort of pressure in a particular spot. It makes me just a little breathless and gives me a slight cough. When I told the surgeon about this, he looked at me skeptically. “Maybe you can feel the nodule inside your throat,” he said. “You have a thin throat, so you might be able to feel it.” In my experience, doctors never believe that you understand your own body. They’re pretty sure they know better than you — after all, that’s what they were taught in medical school. They’re the experts on bodies. But I’ve lived in my body a long time, and I know when something’s not right.

So that’s it. On Thursday I’ll have surgery. Theoretically, the side of my thyroid that is left should take over the function of the whole thyroid. Hopefully I won’t need medication, but we’ll see. I’ll have a scar on my throat. I plan to tell everyone that it comes from the time when I was a pirate queen. Or that I got it dueling in France, but you should see what I did to the Countess. Or that I usually wear a velvet ribbon, and watch out because my head might fall off.

More prosaically, I’ll do my best to get through end-of-semester grading. Then Budapest, then London, then the rest of my life. Half a thyroid is better than none, and I hope we will go on many more adventures together.

(The image is Woman Reading in Bed by Gabriel Ferrier. This is what I plan to look like for about a week after the surgery.)

March 4, 2024

Making a Space for Writing

I’m trying to make a space for writing again.

I’m writing this in my official writing room, or at least what is supposed to be my official writing room. During Christmas it was my daughter’s bedroom, but now the daybed is back to being a place to sit and work rather than sleep, and all the things she brought with her are back in her dormitory, and it’s just me and the desk and the books and notebooks and notes and laptop. And I’m trying to feel as though this is a writing room again.

I suppose I’m also trying to feel as though I’m a writer again.

It’s only the beginning of March, but this semester has already been so eventful. I feel as though I’m living in the middle of a windstorm. Among other things, there have been medical problems to deal with, and in the midst of it all I’ve felt as though my writer self has gotten a little lost. She is wandering at the top of high cliffs, in this wind that is whipping her hair back and forth, pulling at her coat, sending her scarf streaming out first one way then another. She is clutching her hat and trying very hard not to fall over the edge. She is a brave soul, but she has been buffeted by just too much.

And here I am in the meantime, the practical part of myself that works and pays bills and tries to save for the future, that grades student essays and makes lesson plans, and schedules medical appointments, looking at her wandering at the top of that cliff. And I feel responsible, as though I need to catch her hand, pull her back. Poor Writer Girl. What shall I do with her?

I think the only solution is to write again. And that means I have to make a space for writing in my storm of a life. I need a rock and a lighthouse. I suppose this desk and the laptop on it will have to do. The desk is the rock, the laptop is the lighthouse. And my job is to keep the light going, because there might be lost ships out there somewhere.

I’m quite sure I’ve let this metaphor run away with me. Metaphors tend to do that — they steal away the thing you were trying to say, and they tell you, Just go with it. It’s poetry.

Anyway, where were we? In my writing room.

The thing is that my brain doesn’t work right if I’m not writing. Somehow I need the activity of putting words on a page to recalibrate my brain, which makes it sound as though my brain is a compass, but not the old-fashioned kind, which doesn’t need calibrating. It’s a modern electronic compass, and sometimes it doesn’t point north anymore. And then my ship gets lost, and there are the rocks . . .

Now I’ve done it again, let the metaphor run way with me (or sail away with me), but honestly there is such a pleasure in writing these words and sailing away with metaphors, because here I am writing again and it feels like standing on that cliff, on a perfectly sunny day, and seeing all the sailboats down below, with puffs of wind blowing them here and there. Somehow, writing is exercise for a part of my brain that doesn’t get exercised otherwise. There is a part of my brain that simply loves putting down words and feeling the flow of them, like a river flowing to the sea or a scarf flowing through my hands.

Of course, making space for writing is not just about the physical space of my office. It’s about time as well, and I really have no idea when I’ll be able to make the time. But if I can make the space, I can make the time somehow. Anyway, that’s what I’m determined to do. And in the meantime, I’m going to make some changes to this room. I’m going to add a bookshelf, because I have piles of books everywhere. And I’m going to add a stand for my printer, for paper and the other supplies a writer needs. Because sometimes the best way to start a new habit, or restart an old one, is to redecorate.

There is something I realized once that has stuck with me, and maybe it will stick with you as well. Here it is:

In order to write a book, you have to become the writer who can write that book.

That goes for short stories, poems, essays — anything, really. In order to write something, you need to become the writer who can write it. Setting aside a space for writing won’t make you into that writer, but it will give you a place where you can transform. Where you can sit and work and grow into the person you need to be, in order to write the next thing. A writing room is a place of transformation. Who knows what you will become . . .

And now I have sat in my writing room, playing with metaphors and putting words down on paper (or rather, a laptop screen), and it feels as though a part of my brain has breathed out again — as though it had been holding its breath, and now it can exhale in relief. It feels as though I can see farther than when I started to type, and as though when I go to sleep, I will dream of lighthouses.

(The image is The Veiled Cloud by Charles Courney Curran.)

January 22, 2024

Bad Books by Good Writers

“The orchard was very silent and dreamy in the thick, deeply tinted sunshine of the September afternoon, a sunshine which seemed to possess the power of extracting the very essence of all the odours which summer has stored up in wood and field. There were few flowers now; most of the lilies, which had queened it so bravely along the central path a few days before, were withered. The grass had become ragged and sere and unkempt. But in the corners the torches of the goldenrod were kindling and a few misty purple asters nodded here and there. The orchard kept its own strange attractiveness, as some women with youth long passed still preserve an atmosphere of remembered beauty and innate, indestructible charm.”

–L.M. Montgomery, Kilmeny of the Orchard

It feels a bit strange to write that I had not read Lucy Maude Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables until just recently. I had read a number of her other books, including other Anne books and some Emily books (about the adventures of Emily of New Moon), and several collections of her short stories. I loved her as a writer, but in some obscure way I was afraid to read Anne of Green Gables, her most famous book. I was afraid it would not live up to my expectations. I had watched the Canadian movie version, in which Anne was played by Megan Follows, and I loved it so much that I was worried the book itself might let me down.

I should not have worried. Anne of Green Gables is a wonderful book, both touching and very very funny.

Just before reading Anne of Green Gables, I read Kilmeny of the Orchard, and it’s . . . not. As in, neither funny nor particularly touching. It’s the story of a young man, a privileged young man, who goes to teach on Prince Edward Island and meets a beautiful, really stunningly beautiful, really incredibly impossible beautiful, young woman with one mysterious defect (his words, not mine) . . . she can’t speak. They fall in love, because he is basically the first young man she has ever seen, and she is just so beautiful that it doesn’t matter that she has no money, no knowledge of the world outside the farm she has grown up on, basically nothing to bring to a relationship except her beauty and untouched purity, and oh yes, she plays the violin. Plus she can’t talk back, although she and the young man seem to get along well enough because she can write on a slate.

This is a typically icky Victorian plot. You could find buckets of such books in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, and as I’m sure you expected, in the end Kilmeny’s muteness turns out to be psychological. It’s cured by her love for Eric, the young man, which is a good thing because she feels as though she could not possibly marry him with such a defect (her words, not mine). As the novel progresses, all obstacles to their union fall away rather easily, like the fall of a silk robe from the shoulders of Gibson girl. Eric’s rich father could object, but he doesn’t because Kilmeny is just so stunningly beautiful that she would make an appropriate wife for anyone, plus she reminds him of his beloved dead wife, Eric’s mother. Yes, I know, icky.

So there we have it. What kept me reading Kilmeny of the Orchard, other than its very short length (134 pages)? Well, there is my love for turn-of-the-century literature. But there is also no denying that the book is beautifully written. Lucy Maude Montgomery is a cracking good writer, whether she’s writing great books or bad ones. As you can see in the passage I excerpted above. Her descriptions of the orchard, and of Prince Edward Island in general, make up for the weaknesses in characterization and plot. Their loveliness comes not just from the imagery she describes so well that I can see the orchard on that September afternoon, but from the sentences themselves. It’s in the way she puts them together.

“There were few flowers now; most of the lilies, which had queened it so bravely along the central path a few days before, where withered. The grass had become ragged and sere and unkempt.”

What beautiful rhythm. It would not be at all the same if she wrote, as a modern editor might suggest, “The grass had become ragged, sere, and unkempt.” That would not capture the lilting, unhurried pace of a sunny September afternoon. The lilies queened it, as they do. The torches of the goldenrod — yes, I can see that, because goldenrod does exactly that, it stands up and blazes. Purple asters are misty because there are so many little flowers on a stem that from any distance they look like a purple mist. So her images are both evocative and precise.

And this: “The orchard kept its own strange attractiveness, as some women with youth long passed still preserve an atmosphere of remembered beauty and innate, indestructible charm.”

Ok, yes, it’s thoroughly of its era, when old age for a woman was approximately thirty . . . But it’s beautifully written and I love the image it evokes, of the orchard aging in this way. You can see that the spring glory of its flowers has passed, it has borne its fruit, which may have already fallen, but there is something innate and indestructible — imagine the trunks of fruit trees that will stand like strong brown limbs through the winter snows, and blossom again in spring. In a sense, the novel is a love story between an author and the orchard she created.

Honestly, if I were Kilmeny, I would write on my slate, “Thanks, Eric, but this is a really nice orchard, I mean I really like this orchard, so have fun in the big city but I think I’ll be fine here. I have a violin, after all.”

The thing is, Kilmeny of the Orchard was published the year after Anne of Green Gables, and Anne of Green Gables is a really good, I mean really really good, book. It’s got all the beautiful language, but it also has perceptive characterization, excellent pacing and plot (will Anne be allowed to go to the church picnic with Diana and the other girls? I had to know. I could not put it down and stayed up until 2 a.m. to find out), and the one thing Kilmeny of the Orchard does not have at all, not even a little — it’s very very funny.

I had to find out how the author of Anne of Green Gables could have written Kilmeny of the Orchard, and the answer is that Kilmeny’s story was written earlier, as a magazine serial. After the success of the red-haired orphan who breaks slates over people’s heads, Montgomery’s publisher said “I want another novel and I want to publish it a year later,” and this was the only thing Montgomery could give him — a patched-up serial, while she wrote her next Anne book. I suspect that publishers have been responsible for bad books in exactly this way since they invented themselves . . .

While trying to figure out how Kilmeny of the Orchard came into being, I came across a review on Goodreads that I found particularly illuminating. The reviewer said something like, “Kilmeny is the romantic heroine Anne imagines herself to be, but can never become.” And I thought, yes! That makes perfect sense! Kilmeny has long black hair and is impossibly beautiful. Anne has red hair, as she often laments, and the most endearing thing about her is that she simply never shuts up. Anne of Green Gables is filled with long paragraphs that are simply Anne going on and on while Marilla says, “The muffins in the oven are burning.” And the muffins burn, and then we listen to Anne lamenting the burned muffins and her red hair, and spinning a new romantic adventure for herself, for another couple of pages.

I don’t have any great wisdom to offer here. Just a few observations: First, good writers are going to write bad books, sometimes. That’s just how it is. Both readers and writers should expect it. Second, if I really love a writer’s style, I will read a bad book by that writer, regardless. I will read L.M. Montgomery’s bad books with pleasure, ignoring Eric and even Kilmeny, pretending that it’s really a book about an orchard, and the happy ending is that those annoying protagonists finally leave the wonderful, magical orchard alone to dream in the September sunshine.

(The image is the first edition of Kilmeny of the Orchard, published in 1910.)

January 8, 2024

Turning Fifty-Five

The strangest thing about turning fifty-five is that it doesn’t feel any different from turning forty-five, or even thirty-five. I suppose thirty-five was different because I was pregnant with my daughter, but I don’t remember feeling any particular age. And I don’t feel any particular age now. Twenty-five was different because I was working as a lawyer and trying not to be completely miserable in the world of corporate law. It was actually more different than fifteen, when I was still in high school and still myself, more or less. Still the self I am now, rather than trying to be someone else. I was writing poetry and reading literature, which is more or less what I’m doing now.

It feels as though the years between fifteen and fifty-five have been a return to who I am — a long, hard road that has taken me back to myself.

I mean to write this post last year, around my birthday, but I was in Budapest and so busy that there was no time. I suppose this post is really about time, about what a strange thing it is. I didn’t think much about time until I became a lawyer. Of course as I was growing up, there was time to wake up, time to get to school, the schedule of the school day signaled by a bell I hated the way a cat might hate the bell around its neck. In the regional dialect I grew up with, in Virginia, it could be “high time” for something, meaning it should happen now, and maybe should have happened some time ago. In college there were syllabi telling me when to turn in assignments, when exams where scheduled. There was a rhythm to the semester. The first time I remember really being conscious of the passage of time was in my early twenties, when it became “high time” for the girls I graduated with to get married. I remember feeling as though, if I was not married in my early twenties, I would have somehow missed a crucial step in the dance my girlfriends and I we were all dancing — as though life were one of those balls in a Jane Austen novel.

Later, I realized this was once again regional. The female law school students I met in Massachusetts were definitely not getting married in their early twenties — there was a ten-year difference between what was considered normal in Virginia and normal in Massachusetts. Instead, they were thinking about how long it would take to make partner in their law firms, and planning their lives around that particular track. In the law firm, I had my first experience of time and mortality. All of my work had to be accounted for in fifteen-minute increments so the law firm could bill by the hour. We lived under the tyranny of the billable hour, just as I had once lived under the tyranny of the school bell. One day, I remember trying to calculate how many billable hours there would be until I died. That was the beginning of the end of my legal career.

The next time I remember feeling the pressure of time was in my early thirties, when I thought, if I don’t have a child now, I may not be able to. I was in graduate school, my then-husband was in graduate school, and it was not an easy time to have a child, but then everyone said there was no easy time, really. And I was thrilled when my daughter was born. That was the beginning of a different relationship with time, because when you have a child, you live with a small being whom you fervently hope will outlive you, will have a long and happy life after you are gone. You are presented every day with the fact that life is a cycle, and you are part of that cycle. You live with physical evidence of your own mortality. Of course, most of the time you’re too tired to actually think about this, but it’s there, like existentialism for John Paul Sartre.

And what is time now? My daughter will be turning twenty this year and as she had gotten older, I’ve lost that sense of time as so physical, so urgent. I feel, once again, somewhat immortal. I have to remind myself that my time on this earth is limited, and that I have things to do. Sometimes I wonder how much time I have left. But it’s more as motivation than existential crisis, because the other thing I’ve learned over the years is that there are two kinds of time. The first is the time of the bell and the billable hour, which passes and passes and passes, inexorably. But at the same time, there is yes, another kind of time — the time of subjective experience, in which a moment can last forever or a day can pass all too quickly. We can lose time, as when we scroll on our phones and realize, hours later, that time has passed and we have barely experienced the world. And we can have moments of exquisite being when we are fully alive, and it seems as though the experience will never end, that it’s etched in eternity. I have so many of those potential moments left that I’m pretty sure I’m going to live forever. More practically, my grandmother died at ninety-six, and all the women in my family live a long time. So there is that.

Mostly what happens as you get older, I think, is that you return to the essential self you had when you were young. Somehow society covers it up, like layers of varnish on an old painting, and then time cleans it again until you are back to the original layer, like a Vermeer after a museum restoration. At least, that’s my theory today, and it could be wrong, or only apply to me. But I feel closer to my fifteen-year-old self than my twenty-five-year-old or thirty-five-year-old selves. And when I think about all the things I still want to do in my life, I think, there’s plenty of time — but I’d better get started.

(A photo I took of myself on my birthday, already thinking I would write this post. No makeup, no filters, but excellent lighting by the city of Budapest.)