Theodora Goss's Blog, page 3

September 28, 2023

Listening to Ben Okri

One of the nice thing about working for a university is that there are always speakers and events, which are often free or not very expensive for students and faculty members. Last week, I was able to attend a reading and Q&A session with the Nigerian writer Ben Okri, and I wrote down a few thoughts that I wanted to share here.

First, it’s always fascinating to hear good writers talk about their process. I’ve only read a little of Okri’s work so far, but what I read was an essay on writing that was very smart, so I wanted to hear what he had to say. And I found that his perspective on being a writer from Nigeria was similar to what I’ve heard from at least some Central European writers. His view on writing felt right for Hungary as well — at least for the way I write about Hungary.

Okri lived through the Nigerian Civil War of the late 1960, which resulted in mass casualties from both the war itself and the resulting poverty and starvation. The war followed a long period of British colonial rule, so the people of Nigeria suffered the double trauma of colonization and civil strife. It was a very different environment than the one we were experiencing at that reading, sitting in conference room chairs arranged in neat rows, in a large room with floor-to-ceiling windows that showed the Charles River at night, with the lights of Cambridge across the river and Boston to the right of us, as the river bends. If you looked carefully, you could have seen the gold dome of the Statehouse. It was the serenely privileged light of a city that had not been in a war for two hundred years, and as I sat there, I remembered the spring of 2022, when I was in Budapest and the war started just one country over, in Ukraine.

First there was an introduction by the novelist Ha Jin, then a conversation, then a reading, then a Q&A. Here is what Okri said that struck me enough that I wrote it down, and I scribbled for some of the conversation and most of the Q&A. The Q&A always ends up being the most interesting part of these sorts of presentations, and it is always left for last, so it’s usually done in a rush — which is unfortunate.

Nigeria, Okri said, according to my notes, is a palimpsest of realities — like Hungary, I would add. In that sort of situation, Western conventions of storytelling don’t work. When you have sedimented realities — that was the word I wrote down, and I think it came directly from him — you can’t tell a story in a linear way, so your choice of structure is already poetic and fantastical. Which means (I think, if I’m transcribing and explaining correctly), that sort of reality can only be represented, realistically represented, in a non-Western, non-linear fashion. He mentioned disliking the term magical realism, and I’ve noticed that everyone described as writing magical realism dislikes the word — it’s only people who themselves claim to write magical realism, usually from a solidly European tradition, who seem to like it. And he said that he started with his mother’s stories. That was his original experience of narrative.

I wrote down a series of statements about story. This is a sort of paraphrase:

Stories are the oldest human technology. They organize the chaos of existence. They create a clarity within that chaos, allowing us to see the world. They simplify, and in doing so, they give us a path forward. Stories are also a storage mechanism for cultural wisdom. They function as coded realities. They hold time — he paused, then said, “They hold the essence of time” (this is a direct quotation, I believe). I think I understand this in several ways. Stories hold the time of the story itself — they contain something that happens, a particular narrative, like a cup. They capture time, but they also take time. A story is not a painting: to experience it, you need to spend the time to read it. I feel as though this is somehow very important, but I’m not yet sure why. It has to do, I suppose, with the distinctive form of the story — it is not even a poem, which happens all at once. A story is the closest artistic event to a human life, which also takes time. Then he said, “I’m fascinated by stories that are impossible to tell,” and, “The deepest things are impossible to find a narrative for.”

When he was asked about what we face right now, the overwhelming problem of climate change, he said, and I’ve written this down on a card so I can remember it:

“We either transform or we perish.”

Write that down, because you’ll find that you need it in your own life, but we also need it as a civilization. Either we transform as a global society, or we perish, taking a lot of other species with us. We’ll find out which it is in the next few generations.

The most important idea for me, in terms of writing, came during the conversation, and then I asked about it in the Q&A. It was the idea of an aesthetic code. The aesthetic code of a story, said Okri, is the code by which the story can best be understood. For example, he wrote a story and later realized that it could best be understood as a series of gaps. This reminded me of what Henry James wrote about his novel The Golden Bowl: that when he started writing is, he envisioned it as a movement. Everything would revolve around Milly Theale without touching her. She would be the delicate center of the novel, but the action would move around and around her. When I first read this, I was fascinated by the idea of starting a novel with a movement. But I think many stories can be envisioned in this ways — they can be visualized. They have a particular shape, like sculpture or dance. In the Q&A, I asked him if he was aware of the story’s aesthetic code while he was writing it, and he said that sometimes, not always — that understanding it was like grace, but a grace that is earned through hard work. Which I think is a wonderful thought.

The other most important idea is something I’ve thought about before: it’s of the story as fractal. Okri did not actually call it that — he just said that the story should contain everything, just as reality contains everything. In reality, you look at one small thing (say, the way someone walks), and it contains so much — the whole history of that person, the things that have happened to them. Actors know this. When a really good actor develops a character, she thinks about how that character moves, and the way a character walks down a street can project the essence of the character. The small part contains the whole. Okri implied that stories functioned like this — although they show only a small part of reality, they somehow contain all of it, and the story itself is a fractal in that a small part of it also contains the entire story, so that a sentence can express the essence of that particular narrative (just as a character’s walk can express the character). I’m not sure I’m explaining this well, and I’m also not sure this is what Okri meant, because so much of my own thinking is wrapped up in it. But I remember reading, once, that a Jackson Pollock painting from his mature period had that fractal structure, whereas one from his earlier, less mature period did not, and it affected how I think about writing.

He also said, and here I’m paraphrasing again, that a novel walks in a constant dialog of oppositions. This reminded me of how I used to talk about writing when I was teaching in an MFA program. I used to say, what are you putting in tension in this scene? What things are pulling against each other? It doesn’t matter how much action you include, if nothing is in tension. Without that tension, your reader won’t feel anything, won’t be interested in anything. Things need to be in opposition to each other, whether it’s the galactic forces of good and evil or two friends having a disagreement.

Finally, he talked about dreams as a parallel reality, and described writing as making dreams real for people. I think this is important. Our minds can’t deal with the world all the time. We are created to shut down for part of every day, so that our minds can go do something else. They can go elsewhere. I have found that my dreams are often ways of processing my daytime anxieties, which is probably why I so often dream of being lost in either large cities or their equally large transit systems. Or more recently, in enormous airports. Stories can function in the same way. They are waking dreams that help us organize and deal with the anxieties of our existence. They create meaning for us.

And my final note from the reading had to do with The Odyssey. I didn’t write down the specific context for this statement, but toward the end of his talk, Okri said that it encapsulated a basic human narrative: “We’re all just trying to get home.”

I think that’s true, but I think we’re also all just trying to create home, to find our families, belong and find meaning for our lives. And that is what stories help us do.

The Famished Road is the book for which Okri received a Booker Prize.

September 10, 2023

Emotional Energy

I’m too tired to write this blog post.

Last week I tried to do all the things — all the administrative things I need to do at the beginning of a university semester. I still have a lot to get through. There are receipts to file, meetings to attend, emails to send or answer.

And I tried to write as well. I’m most of the way through writing a story I thought of several years ago, and that I started months ago but that was interrupted by teaching in London during the summer. Hopefully it will be done in the next few weeks.

And I had family obligations to deal with, which are not purely obligations — for example, it’s a pleasure to spend time with my daughter. Nevertheless, the start of the academic year is always stressful, for students and parents alike.

And now it’s Sunday morning, and I’m trying to write a post I’ve been thinking about for a while, on why we sometimes get so tired — and I’m too tired to write it. But I’ll try, nevertheless . . .

This post comes from a realization I had recently — or perhaps it’s less of a realization than a hypothesis. I remember that I was in Budapest, and it was afternoon, and I thought, What’s wrong with me? Why do I get so tired sometimes?

There are ways in which my life can be physically tiring. I had just come back from London, where we were taking the students on excursions every week, and on most days I was walking at least two hours, to and from classes, to Sainsbury’s and Marks & Spencer for food, on street tours of London or in various museums. But I realized that I did not mean physical tiredness, that physical tiredness by itself did not give me that sense of exhaustion I sometimes felt, an exhaustion so deep that all I wanted to do was lie down for a while, someplace light and airy, or escape into the pages of a really good book.

What produced that kind of exhaustion? Sometimes, teaching three classes and holding office hours — after a long day, I would need to lie down for a while. Usually I would not lie down, but would go on working, because teaching would also give me ideas, would inspire me as well, so I would have all sorts of things I wanted to research, to prepare for the next lecture . . . But I would feel that same sense of exhaustion after a morning of answering emails, and to be honest, after a morning of writing. I would feel it after spending a day at a conference or convention, even if I had a wonderful time with other academics or writers. And after spending time with family.

Of course it wasn’t always exhaustion. Sometimes I would be just a little tired, but if I pushed myself, I would get more and more tired, until yes, there I was, completely exhausted. Why?

My hypothetical answer is that some things take emotional energy. Teaching of course, because at the same time as you’re explaining the history of rhetoric or how to use MLA citation format, you’re intensely aware of the students in the classroom. You know who is paying attention, who is looking at emails on their laptop, who has a question they are too embarrassed to ask. It’s a kind of teacherly intuition. Answering emails takes emotional energy, because you’re projecting yourself into the recipient, trying to see the email from their perspective, editing to make sure that recipient will understand what you’re writing. Similarly, with creative writing, the writing I love — that takes energy too. I’m projecting myself into the story, into the minds of the characters. I’m living in them for a while. And at the same time, often, I’m also projecting myself into the minds of potential readers, trying to see the story both from my perspective as a writer and from their perspective. Will they need a paragraph break here?

Being a parent always takes emotional energy. It’s intensely rewarding, and there are wonderful things you get back for the emotional energy you expend, but I have to be honest, and I think other parents would say the same — it can be tiring. Friendship, I find, doesn’t take the same emotional energy. Sitting and talking with a friend is closer to an exchange — you get energy at the same time as you give it, and after meetings with close friends, I find myself refreshed. It’s like reading a good book. Reading, if it really is a good book, also gives me energy. Faculty meetings take energy. They’re like teaching, in that I usually come away from them with ideas, things I want to try. But it takes energy to listen, interact, to be completely present. It’s the same for a conference or convention.

When I say that something takes emotional energy, that it tires me, I don’t necessarily mean that in a negative way. Teaching, writing — these are all things I want to do. I’m happy to expend energy on them, just as I’m happy to expend physical energy on going on to parks or museums. What I was trying to understand is how they tired me, what sort of energy they required. And I think it’s emotional energy — the energy that flows out from you when you’re interacting with another human being, even hypothetically. Of course you can get energy from another human being as well — which is why, I suppose, I receive emotional energy from meeting with friends or reading a good book.

I suppose the important thing is, if you’re tired, to understand what kind of tired you are. Are you physically tired? Emotionally tired? Spiritually tired? Because there are different ways to deal with each kind of tiredness. For physical tiredness, you need to rest and sleep. For emotional tiredness, sleep is important as well, but so are taking walks in the park, reading books, meeting with friends. For spiritual tiredness, which is a category of its own, the remedy (I think) is something like spending time with trees and looking at the sky. You need to somehow drink in the essence of existence.

At least, the above is true for me. But I know that people are different, and fall in different places on the spectrum of introversion to extroversion. It may be that you, if you are an extrovert, get your emotional energy in large crowds, all shouting for a sports team. Or from being on a stage in of an audience, channeling their emotions. I am on the introverted arm of that spectrum, and my energy comes from small, quiet things, plus chocolate.

Today I’m so tired because last night I made a mistake. After a day of writing and dealing with administrative issues, which included talking to a chatbot and three different customer service representatives because two airline websites were both malfunctioning (Swiss and Lufthansa, I’m looking at you), plus trying to deal with UPS, I was so tired that I did not have the energy to get ready for bed. So I stayed up too late watching silly video clips on YouTube. Even thought watching films and videos involves absolutely no physical energy, I always find that it takes quite a lot of emotional energy, in a way that reading does not. I’m more tired after a movie than before. I did not get to sleep until much too late, so today I am both physically and emotionally tired. Maybe even a little spiritually.

I have a lot of work to do. But sometime today, I’ll take a walk in the park and do some reading — not for work, purely for pleasure.

And you know what? Now that I’ve written this, I feel better, more energetic. Writing may take emotional energy, but it also gives me something powerful, which is that I’m talking to you, whoever you are, and that’s a bit like communicating with a good friend.

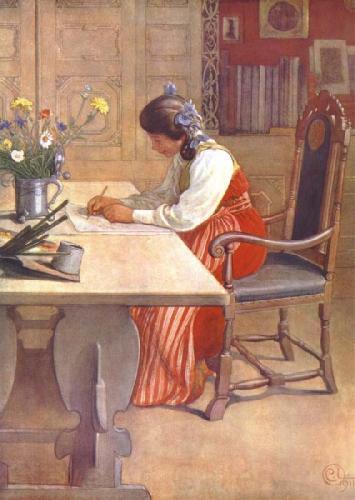

(The image is Fresh Flowers by Lee Lufkin Kaula.)

September 2, 2023

An Elegant Woman

I saw her on the airplane from Budapest to London. I saw her first from the back, and I thought she must be a girl, around fifteen or sixteen, because she was so small and slender. She walked like a teenager. Then I noticed her bun of gray hair. And when she turned, I realized she was closer to eighty-five than fifteen. She had a small, elegant head with high cheekbones and tan, wrinkled skin, an aquiline nose. And her hair, quite a lot of it, all different shades of gray, was pulled back in the high bun I had seen.

What had deceived me, in part, about her age was that she did not move like an eighty-five year old woman. She stood straight and she moved easily, naturally. Of course I know I’m dealing with stereotypes here — not all women move the same way at any age. But I remember how my grandmother moved at that age, and this woman moved like a yoga instructor, or maybe a former ballet dancer, the kind that becomes a teacher and stands at the front of the ballet class in character shoes, more poised than any of her students. She reminded me of my grandmother, actually. My grandmother had those same high cheekbones, and similarly her cheeks had been hollowed by age, a look that young actresses try to achieve by having the fat sucked from beneath their cheekbones. Be patient, I would tell them. Age will etch your cheeks. Age will make you elegant. My grandmother also had a full head of gray hair, although hers was short all her life.

Like my grandmother, this woman was Hungarian — I know because I heard her talking to a man who might have been a son or son-in-law, and a little girl who was certainly a grandchild, who hung on her hand. She was wearing what I thought was a knit dress until I later saw it in the window of the High Street Kensington Zara and realized it was a sweater-skirt combination, in various shades of gray that matched her hair. Very elegant, and probably expensive. Her shoes had the sort of heels that are more comfortable than flats — medium sized, thick without being chunky, very walkable. And again, elegant.

I noticed all this in the relatively short time I watched her walk onto the plane, then wait in the line to disembark, and then disembark — both times I was behind her. I noticed so much partly because I notice women’s clothes. As they pass on the sidewalk, or as I see them sitting or standing on public transportation, I notice and say to myself, Oh, I like that! What if I tied my scarf the way she’s tying hers? Ok, I see wide legs are in now, and they look good with a long sweater. But could I wear that, at my height (or rather shortness)? Oh, no, not those shoes. She’s going to trip over them any minute . . . It’s not really a way of judging the wearer (although sometimes, to be honest, it’s a way of questioning her judgment). It’s more a way of figuring out what might suit me, who I want to be. At least in the matter of clothes. And of getting new ideas, because I’m not really very creative when it comes to clothes. I mostly know what suits me now, because of all the mistakes I made in the past — years and years of mistakes. We won’t talk about my unfortunate Laura Ashley phase, when I tried very hard to be that romantic boho girl. Or the phase, in graduate school, when I decided to wear only black, day after day. I don’t remember why, but I had just gone back to school after four years as a corporate lawyer, and I think I was in rebellion against all things corporate, against hierarchy and patriarchy (embodied in the very real, non-theoretical hierarchy of partners that I had to work with, some of them gleefully nasty to new associates, both male and female). It was as close as I came to punk, in a Victorian mourning, gothic sort of way.

Anyway, my point is that I noticed this particular woman, not just because she was elegant, but because she was old, as I discovered when she turned around. I could call her elderly, but the point I’m trying to make is that she was eighty-five or so and elegant, and I thought, I’m going to be eighty-five too someday. I’m going to be old, and people are going to call me elderly, and I might say, No, I’m just old, my dear. But there’s no guarantee that I’ll be elegant. But . . . she was. So if she was, I could be too? If, at that age, she could be on a plane from Budapest to London, wearing the latest Zara, I could be too?

I’m not afraid of getting old, but I am afraid of getting old the way my grandmother did, slowly losing her ability to travel, to work at her painting and embroidery. No longer tending her own garden, cooking the recipes in the handwritten recipe book I’ve inherited. The elegant woman, speaking Hungarian to her granddaughter, was a slender beacon of hope.

I still have a while before I’m old, or elderly, or whatever you want to call it. But I’m planning ahead, because I know I’ll get there eventually. (Assuming the politicians with the nuclear buttons don’t blow us all up first, which is always possible.) I suspect the most important element of her elegance was yoga or ballet or pilates, one of those disciplines — whatever it was that allowed her to move so freely. And the second most important element was the absolute comfort of the clothes she was wearing, of her sensible but stylish shoes. It took me a very long time to realize that the pinnacle of elegance is being comfortable in your clothes, your skin — of knowing and being yourself.

I’m not there yet, but in the meantime, I’ll keep admiring elegance, wherever I see it. I was not elegant when I was young, as my high school photos (in which I always looked uncomfortable) amply prove. Now that I’m sort of in the middle, I’m doing my best — no longer quite as awkward, intermittently confident. But really, the goal is to be elegant by the time I’m old, like the woman I saw in the airplane from Budapest to London. Here’s hoping that, by the time I’m eighty-five, I’ll get there.

(The image is Portrait of the Princess de Beaumont by John Singer Sargent.)

August 14, 2023

Making a Home in London

Seven weeks is a long time to spend somewhere. It’s not a vacation, and anyway I wasn’t vacationing in London. I was there to work.

Specifically, I was there to teach in the Boston University College of General Studies summer semester, which takes place in London and is one of the most adventurous teaching experiences I’ve had. We don’t just teach in the classroom — London becomes our classroom, and we go everywhere. The British Museum, the Victoria and Albert, the Imperial War Museum, Kew Gardens, Brighton . . .

And my daughter was with me, taking classes on reading Egyptian hieroglyphs. Last summer, when I taught in London, I was mostly by myself, and in that situation I can lead a fairly monastic existence. I suppose the female equivalent of monastic is conventual — when I looked up the female equivalent of a monastery, I was given the word convent, and told that historically a convent was actually a house of friars, now knows as a friary. The point of this etymological rabbit hole is that when I’m by myself, I can live on oatmeal for breakfast, sandwiches for lunch, and soup for dinner, day after day. I don’t need entertainment, other than some books (all right, an increasing quantity of books). And I mostly focus on work. But that’s not enough for a teenager.

So anyway, I was working and living in London for seven weeks, with a teenager. I had to make a home somehow, even in a short-term rental flat.

There is a sort of art to making a home. How do you make a space both functional and cozy? Particularly when you’ll only be there a short time, and you’ll need to leave it as clean and spare as you found it. What are the components of home? I suppose they’re different for everyone, and what you need depends on the place you’re living in. Ours was furnished and outfitted with the basic necessities. But we did find ourselves buying things that would make our lives there more comfortable.

Since I had taught in London the summer before, and we are given some storage space, I had a few items waiting for me: a yoga mat, two blankets, office supplies. I don’t know if office supplies make you feel at home, but they have that effect on me. When I have my scissors and stapler and hole puncher, I just feel much more comfortable, as though I’m in a known and familiar world. And having a yoga mat means stability. It means that on this spinning globe of ours, I have a place to stand on, and a routine for my mornings. It’s like a little bit of my own ground in the larger country of Albion — not quite a garden, but a rectangle of concentration in a strange landscape.

Because London is, indeed, a strange landscape — stranger than Budapest, not only because Budapest is also my home, but because when you travel from the United States to Budapest, you expect Budapest to be different. Whereas if you travel to London, you expect it to be somehow the same — at any rate, you expect people to be speaking English, but there is no such thing as English. There are only Englishes, many of them, with different dialects and accents. Even within London, many Englishes are spoken, and some of them were quite difficult for me to understand, so I was conscious, always, of being in a foreign country, with its own customs that are not those of Boston.

There are of course the obvious differences, people driving on the other side of the street and the car, so that I was always trying to get in the wrong side, and always in danger of being run over. The food is different, the water from the tap tastes different, even the air is different, both from the soft air of Budapest and the sharp air of Boston. The air of London hangs around you like a curtain, often of chilly rain, sometimes of a damp warmth that is different from the dry, bright warmth of Budapest.

In this strange place, how did we make a home? Partly it was by buying stuff, the basic stuff you need for everyday life. Placemats and napkins with daisies embroidered on them. Cheerful bowls and mugs for our breakfast and tea. I made a rule: what we bought had to either be good enough that we would bring it back to Budapest with us, or cheap enough that we could bring it to a nearby charity shop afterward, and donate it so others could potentially use it. Thinking that we could pass it on to others made the purchases seem less extravagant, although we did not buy anything expensive — our primary source of items to pass on was Flying Tiger, and the things we wanted to keep, we found in Marks and Spencer. My favorite purchases were three mugs with animals on them: an owl, a rabbit, and a badger. There is a fourth mug, with a fox on it, but the only one available in the store on High Street Kensington had a chipped rim, and although I went back several times, no fox mugs were added to the inventory. Next summer, I’m going back to London to see if there is a fox mug. (I mean, I’m going back to teach. But the fox mug is an added incentive.)

We also bought a lot of books, too many of course. So many that we had a buy an extra backpack to bring them back to Budapest, and I thought we would be charged for it, but the ticket agent who checked us in said no worries, it’s small enough that I don’t charge you. And he told me about his daughter was also a teacher, but is now a school principal. I think books are like bricks that you use to build the walls of home, and actually in Boston and Budapest, all my rooms are lined with bookshelves. Being surrounded by books is like being surrounded by friends — I know that at any point, I can go have a conversation with Jane Eyre or Ozma of Oz.

So I suppose we build our homes out of little things. Books and mugs and blankets. In Budapest and Boston, I have furniture that I picked out, and rugs underfoot, but the things that make a home are smaller. They’re the pens in the wire mesh cup. The paper flowers in the vases. The pillows scattered around. The things that make life softer and more interesting.

When our time in London was done, we packed up almost everything, gave away what we needed to, and left the keys on the table. We had made a home for a little while, and even for that little while, it was worth it to have bought the mugs with the owl and rabbit and badger (which anyway are now with us in Budapest). I’ll be back for the fox.

This is part of the Boston University London campus near Kensington.

And these were some cakes we bought in a cafe that looked delicious but proved disappointing. We were not in Budapest anymore . . . (I may be biased, but I think Budapest has the best cakes in the world.)

Living in Chelsea . . .

June 17, 2023

How to Feel Rich

I discovered the secret to feeling rich during the pandemic.

Do you remember the Great Toilet-Paper Shortage? When the supply lines failed, and suddenly there was not enough toilet paper, and we were all going to different stores on heroic quests for those magical scrolls of pillowy, or if necessary not so pillowy, positively scratchy, but at that point anything would do, toilet paper? One day, I was almost out of toilet paper and I went into a store — I don’t remember which store exactly. Drug store, grocery store? That day, it was a magical store, because it had toilet paper! I bought a pack plus an extra pack, a big one, and I kept that extra pack in one of the lower kitchen cabinets throughout the pandemic, using a roll as I needed it, replacing it as I could. It was my toilet paper stash, like having money saved in the bank for emergencies.

And I realized that it made me feel rich.

I was not rich — I am not, at this particular moment, by any definition of the word, rich. As a teacher, I am modestly middle class, struggling to pay rent in one of the most expensive rental markets in the world. Growing up, I was even less rich — the daughter of a single mother raising two children by herself. I remember going to college and seeing all the clothes my friends brought with them. So many! How did they get so many? I don’t remember whether we did not have a lot of money to buy clothes, or whether my mother insisted on quality over quantity — I suspect both. My allowance certainly did not stretch to many outfits, and as for quality — well, I’m not sure it makes sense to focus on quality in clothes for teenagers. I still remember the holes I used to wear in my jeans, from sitting on the ground with my friends, falling from a bike or while roller skating . . .

In graduate school, I discovered thrift shopping, because I did not have money to shop in regular stores. And somehow, over years and years, I filled my closet with the very pretty things that other people had discarded — swingy linen skirts, cosy cotton sweaters, even silk blouses with patterns of flowers. And now, I am rich in clothes! And I feel it — that’s the point I’m trying to make. I feel a sense of abundance, of affluence, because I am rich in this one thing.

How to feel rich: have all you need of one thing, plus a little more.

All it really takes is a little more — you don’t need endless toilet paper or clothes. At this point I only buy clothes if I fall in love with something and it seems to fill a space in my wardrobe — if it’s beautiful and I think I could really use it.

But the point I’m trying to make is that feeling rich and being rich are really two different things. It seems to me that the people who are rich, the billionaires of the world, don’t actually feel rich. For one thing, they never look happy in photographs. And for another, they keep acquiring things, as though they were endlessly hungry, endlessly needy. For yachts, mansions, corporations, money money money. I’ve been thinking about why these things don’t make you feel rich.

Let’s take money. For years I had no money at all, or very little — I lived graduate school stipend to stipend. Now I have emergency savings, and that gives me a sense of comfort and security, but money above that is essentially an abstraction. Seeing bigger numbers on the bank balance on my phone doesn’t make me feel rich. It’s all too diffuse and distant — it feels as though it could disappear tomorrow. And the thing about yachts and mansions is, no matter how many you have, it’s hard to have enough and a little more, which is my formula. I mean, I can get up in the morning and say, which of my clothes will I wear today? And then I will get to choose among a beige linen dress, a pair of loose black trousers with a cream-colored sweater, a pink cotton skirt and white t-shirt . . . What do I want to wear today, who do I want to be today, what textures will I feel, how will I move around the world? My closet gives me an wealth of possibilities.

Granted, toilet paper is not quite so romantic. Still, there is something about toilet paper — in one sense, the lowliest form that paper can take. After all, it’s not being used to print great works of literature! Yet there is something so deeply comforting about have the basic needs of our body cared for, and the things that care for them. Like soap — there is something deeply comforting about soap, pillow cases, a pair of sneakers. One of my favorite objects here in Budapest is a really perfect garlic crusher.

But a yacht — and I have to grant here that, never having owned a yacht, I’m imagining how it would feel. But I don’t think I would get up in the morning and ask myself, “Which of my yachts will I use today?” Same with mansions. I’m not sure if it’s the nature of these things — it’s hard to feel anything at all about one of those luxurious yachts I see in pictures, except what Prince Caspian said to Eustace in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, something about if a boat is so big that you can’t feel you’re on the ocean, what’s the point? And if I had enough money for a mansion, I would buy and refurbish an old castle with a tower and a secret staircase, because come on! Of course I would, and wouldn’t you?

But I think there’s also something else — the formula is, enough and a bit more. And you can’t have enough yachts plus a bit more — a second yacht is already too many yachts. A second mansion is already way more space that you could ever use, and to have more than you will ever need does not make you feel rich, I think. It gives you a sense of surfeit rather than fulfillment, like when you eat way too much birthday cake. Which leaves you feeling empty again rather quickly. And then, of course, you need to fill that emptiness–I suppose by getting another yacht.

I don’t know for sure, of course, since I don’t own more companies than I will ever need, like certain billionaires who seem intent on ruining all of them, as well as our planet . . .

What I am fairly sure of is the formula for feeling rich: what you need, plus a little more.

Based on this formula, I am rich in: toilet paper, summer skirts, marcasite jewelry, Keds sneakers, notebook paper, notebooks in general, pens, pillow cases and towels, jars of jam (at the moment), soft blankets for wrapping around yourself, toothpaste, teacups, and very pretty napkins. I am currently not rich enough in chocolate, so I will need to acquire more chocolate pronto. I don’t count books, since I never have enough of those — my need to acquire books seems insatiable, which I suppose is how I am similar to those billionaires who need to take over more and more companies to put on their shelves (that’s where you keep them, right?).

Anyway, there you have it: my philosophy on how to feel rich. What are you rich in?

(The image is Autumn (Méry Laurent) by Édouard Manet. Born the daughter of a laundress, Méry Laurent became a courtesan, the muse and model of contemporary artists, the center of a fashionable salon, and a wealthy woman. She is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. I chose this image because she seems quite content . . .)

June 2, 2023

Living Two Lives

“What’s wrong with you?”

That’s the question I’ve been asking myself for a while now. I’ve been tired, really deeply tired. I’ve done the work I’ve needed to, but almost none of my own work — it’s been ages since I’ve written even a poem, and the short story I’m working on is waiting on my laptop, half-written. As is a novel manuscript.

So, what’s wrong with me?

I think it began after my third novel came out. I was so exhausted from publishing three novels in three years, while teaching more than full time, that I needed time to rest and recharge. I was just getting started again, working on the next project, when the pandemic came. I’m sure this is true for most of us, but that was one of the most difficult and exhausting times of my life. I taught on Zoom, and then in a hybrid format, and after dealing with the challenges of daily living (finding toilet paper!) and teaching during the pandemic (lecturing through a mask!), I did not have the mental and physical energy to do anything else. Just as the pandemic was ending, I was lucky enough get a semester off from teaching to work on a special project for the university, and then for the next semester, I got a Fulbright to teach in Hungary. We started that semester remote, then went to in-person classes . . . just as the war started in Ukraine. I ended up both teaching my university classes and teaching English to Ukrainian refugees. That semester, I was asked to teach an extra summer semester in London, which I did, and in the fall I started preparing to teach in a new program, where I taught this spring.

Yes, it was as complicated as it sounds, and on the one hand, I’m delighted to have had so many opportunities — I loved the Fulbright, love the program I’m teaching in now, am excited to be teaching in London again this summer. On the other hand, just writing all this makes me tired.

The problem, I think, is that I’m trying to live two lives at once. I’m trying to be a teacher, and also a writer. At the same time, I have one life in the United States, and one in Europe. I don’t know, maybe that’s actually four lives, if we think of it as two times two? And of course, I have a daughter who just started college this year . . . That’s a whole other life in the midst of these two (or four).

No wonder there are times when I feel overwhelmed.

This is where I had gotten to in writing my blog post when I had to stop, because there were too many other things to do . . . I had to take my daughter to kendo practice, yes in Budapest (taught in Hungarian and Japanese), and by the time we got back it was too late to finish. The next morning I had to get her off to Hungarian class, and since it’s the beginning of the month, I had financial things to figure out — money to transfer, bills to pay. There are all sorts of things I’m late on (not bills, administrative things). And of course, soon I have to focus on preparing for the summer semester in London.

So what’s wrong with me? Maybe it’s simply that life has been overwhelming for a while. I’m hoping that it will calm down, and I will be able to focus on writing again. After all, I’m writing here, now, right? That’s something.

I started this blog post with “it’s been ages since I’ve written even a poem,” but between the time I started and the time I’m writing this — now, this minute — I wrote a poem. I wrote it while waiting for my daughter to finish her kendo class, sitting in the rose garden at the Millennium Háza in the Városliget, which means the City Park. It’s a large central park in Budapest, very beautiful, with tall old trees and winding trails, with museums and botanical plantings, a café and a hill for dogs to run on, a closed garden of textures and scents specifically for those who are blind or have disabilities related to sight. Right now, in June, the rose garden is filled with blooming roses. They inspired me the way they always do — that is, I think roses are very strange flowers, wise and secretive, hiding whatever they know within their ruffled petals. They are stronger than they look, and of course they have thorns — we know they do, and yet we forget about the thorns, or at least I always do. I reach for the beautifully scented blossoms and get pricked.

The poem I wrote can be found on my poetry site, so if you’re interested, you can find it there. It’s called “Portrait of a Lady.” I’m not sure where it came from. Like many of my poems, it just happened. I wrote the first stanza:

She sits on a stone bench

in the city park, under a bush

of pink roses, probably

something like Maiden’s Blush,

because they have so many

petals — you know the kind

I mean, that blossom in June

and release, if you lean in closely,

the most delicious perfume.

The poem is not about me, of course. But I was imagining another woman sitting where I was sitting, reading a book (I had brought several — I’m always afraid of running out of books). And I wondered what her story might be, and then I thought — whoever is watching her, writing a poem about her, doesn’t know and can’t know. But the roses know, because they know everything. There is a reason we say that whatever is secret is told “sub rosa.” (I don’t mean the technical reason, having to do with roses on ceilings. I mean a mystical reason. Roses just know. Remember that Antoine de Saint-Exupéry made the two great loves of his Little Prince a fox and a rose.)

Why did I write a poem, there and then? After all, I had books with me, three of them (just in case I ran out of books). I could have read one of them. Instead, I imagined something and wrote it down.

And that, in the end, is what is wrong with me. I have a mind that does that — that makes things up and writes them down, that sees secrets in the roses. And also a mind that gets overwhelmed by the demands of the world, and then gets angry and desperate because it can’t do what it does naturally, which is hold conversations with foxes and roses, and scribble silly rhymes.

Where have I gotten with all this? I have no idea. Except that I’m really thoroughly tired of not writing about roses or Budapest or whatever else. And I don’t have a solution, exactly — I still have half a short story, not to mention half a novel, on my laptop. But even writing about the problem is clarifying.

(The writer in the rose garden, after having written a poem.)

May 7, 2023

Finding the Paths

There is a story I remember, although I don’t remember where I read it. It’s about the president of a small New England college, in New Hampshire or Maine or Vermont, one of those northern states. He wanted to renovate the central lawn of his campus. Between two academic semesters, a beautiful green lawn was laid down — a rectangle right in the middle of campus, between all the old college buildings. When the grass had grown into a rectangular green carpet, the head groundskeeper said to him, “But there are no paths.” The college president said, “Just wait. In a few weeks, there will be.” When the college students returned, they started walking across the grass, and where they walked the most, they wore it down into dirt. The college president said to the head groundskeeper, “There are your paths. Put the bricks down there.”

I remember this story partly because I’ve lived and worked on college campuses, and you always see the auxiliary paths. There are the official paths, the ones in brick or concrete or asphalt, where students are supposed to walk. And then there are the auxiliary paths where they often actually walk, when the official paths are inconvenient — when they are not the quickest way between two buildings, for example. A long time ago, I used to ride horses, and you would see these sorts of paths across the field as well, made by the horses when they walk in single file. They would create their own preferred paths, then use them over and over again. Human beings are, in some ways, not that different from horses. They decide where they want to go, and the paths remain as evidence of their decision-making process. The official paths are an ideal, a vision of the planner or architect for how the field should look, where the people should walk. The auxiliary paths are the reality of how people move and interact.

I was thinking about this recently because I’m trying to redecorate my apartment. It was very pretty before, filled with furniture I had picked up here and there, some of it from antiques stores, some of it from thrift shops, none of it very expensive but all meaningful because they came from the days when I was a graduate student and had very little money. But I realized that there were spaces in the apartment I was simply not using, furniture that was serving merely a decorative purpose. And an armchair should be more than just decorative . . . Also, my life had changed — my daughter had become a college student, and my apartment had to work for her as well as for me. It needed, for example, not a pretty antique armchair, suitable for a tea party, but a big comfortable one to flop down in, to curl up in and read a book.

So I became that college president watching students walk across the grass, although I was the president as well as the students. My apartment was the grass. I observed the way I used it: Where did I spend time? What did parts of it did I use, and how? What did I really need to make my life in it productive and comfortable? Because that apartment also had to work for me — it was my office as well as my living space. It was where I worked and wrote and often researched, because all my books are in it, ranged around the walls in shelves. There is a sense in which I live in a library that is also an art gallery, which just happens to have some furniture in it.

I ended up changing quite a lot, turning the apartment around so the former office became a bedroom and vice versa. And I’m not done yet–I still need a big, comfortable sofa to flop down in, to curl up on and watch episodes of Hercules Poirot on BritBox. But it’s an interesting exercise, to observe yourself and try to figure out who you are, as opposed to some ideal, some vision of yourself that you created in your head. Because at least some of the old furniture came from who I thought I was supposed to be, or thought I might become. But I never actually turned into the person who would have tea parties with guests sitting upright and elegant. When I have guests, they want to flop down on comfortable sofas as well, drinking from big mugs of herbal tea.

There’s still work to do on the apartment, but I wanted to write about this idea, that you have to find your paths, figure out what you actually do, who you actually are, even for something as seemingly simple as buying an armchair.

(This is a path in the Halls Pond Sanctuary, where I took my students on a field trip after we had studied the essays of Emerson and Thoreau. I wanted to them to experience a bit of nature themselves, to pause and breathe in the middle of a very busy semester.)

April 10, 2023

Work in Progress

I should warn you in advance: this blog post will be a little depressing. Its title comes from a Facebook post I saw a few months ago, in which a Facebook friend, although someone I don’t know personally, posted about a friend of hers, an author, who had recently died much too young, in her forties, after the publication of her first novel. The post made me so sad — so young, and just after her first novel had been published! I followed a link to the author’s website, and there it was: “This website is a work in progress.”

It felt like a punch in the chest. Here was a woman, younger than me, who was trying to build a writing career. She had just accomplished what is often the first big step, the publication of a novel. She was in the middle of creating her website. And then . . .

It was, inevitably, a moment of confronting my own eventual mortality, of wondering how many years I had left to write in and how much I could accomplish during that time. And I thought, “I’d better update my website.” But in the middle of that existential panic, I also had another thought: that no matter how long my life lasts, it will probably always be a work in progress. There will probably never be a moment when I say, “That’s it, I’m done, I finished what I came here to do.”

I remember reading that in an interview, Jorge Luis Borges, then in his 90s, told the interviewer, “Someday I hope to write the novel that will justify me.” There he was, famous and accomplished, but he wasn’t finished yet. And then I thought, when that moment comes for me, I hope not to be finished yet. I hope I’m working on a new project, thinking, “This one is going to be really good.”

At that point, the words “work in progress” became a promise rather than a sign of failure. I thought, I want to be a work in progress, up to the very end.

Who knows how many years any of us has left. Who knows what, among all the things we create, will last. All I can hope is that among all the things I create, for however long I can keep working, there will be something — a novel, a story, a poem — that will justify me. That will mean I have done whatever the bits of ancient stars that went into creating me were meant to accomplish.

(The image is Hilda by Carl Larsson.)

February 5, 2023

Little Green Pockets

When I was a child, I sometimes had trouble falling asleep at night. So I would lie in bed for a while with my eyes closed, just imagining things, stories of sorts, or scenarios. One of them went like this. I would imagine all of the streets around our house turning into rivers, the parking lots into lakes. The houses would turn into hills, and the people in them into animals of various sorts. I would imagine what sorts of animals they would turn into, based on their personalities. All around me would be a natural landscape. I would be the only human being left in the wide world, able to wander around this reconstituted garden of Eden. I don’t think I ever thought about the practicalities — what I would eat, for instance. By that time I was already asleep.

We lived in a standard American subdivision that might have come out of a teen movie from the 1980s or 90s. It was arranged around a long, circular road, with smaller streets running off it. On those smaller streets were detached houses in the middle of green lawns, except for one small area of attached houses and even apartments. We lived in one of the attached houses, without a lawn but with a small garden in the back. It was one of the newest subdivision spreading out from Washington, D.C., and there was still a lot of green space that has since disappeared. Back then, the subdivision was surrounded by forest, and the kids could still go play in the forest, as kids did at the end of the last century. We were perpetually on our bikes, riding around the streets, or walking to one another’s houses. There were two schools in the subdivision, an elementary school and a middle school — we were bussed to the high school, which was in the middle of farmland. Beyond the subdivision spread more farmland — we were at the edge of suburban America, back then. Still, I longed for more green space.

Since then, I have lived in many places, many of them quite urban. But I’ve always tried to live somewhere I could see trees out the window, or hear birdsong. I’ve always tried to have a little pocket of nature nearby, for my mental health. It means a lot to me that my Boston apartment is on a quiet street with ancient linden trees that drop their yellow leaves all over the road in autumn, and that I have a little garden, just a strip along the side of the house but I’ve put so many plants into it and over the seasons I can watch them grow, bloom, die back and sleep under the snow. And in my Budapest apartment, I see the trees in the park of the Nemzeti Múzeum. I love that view, and I think I need it as well.

I think most of us need much more nature than we get.

I love teaching, but when I go to teach in the morning, I pass one of my least favorite views in the world. First I walk through the tree-lined streets of Brookline, where the sidewalks are built the old-fashioned way: between strips of green, usually on one side a little garden by the house or apartment building, and on the other side the strip of green between the sidewalk and the road, with grass and tall trees. It’s like a sidewalk sandwich: green, concrete, green. The trees tower above me, and I can hear birds, see a glimpse of the blue sky. Then I emerge onto Commonwealth Avenue, and the view changes. Either way I look, it’s concrete concrete concrete. The long river of concrete that is the avenue, with a tram line going down the middle, broad sidewalks on either side, and very little green. Commonwealth Avenue has gotten better in the last few years — it had to, since it had a reputation as one of the most dangerous streets in Boston, the site of numerous accidents. In places, trees were planted. Right now they look like sticks sticking (stickily) up from small square patches of brown dirt. And there is a protected bike path. But either way I look, I see so much concrete, and in the distance a mountain range of office buildings, glass glass glass, glittering in the sun.

Why are trees put in those little square spaces? Why are the squares either left as dirt or covered with metal grates, as though the trees might escape — or, I’ve seen more recently, a sort of spongy asphalt that I assume is a new technology, the latest in street tree design, because it must let the rain through or the tree would die. But it looks so strange to see trees growing out of what looks like playground plastic asphalt. I feel sorry for the trees — they look lonely, all by themselves, with no birds to sit on their branches (birds stay where there are more trees, more cover), no squirrels to climb up them, not even grass to talk to. I wonder where their roots go, under the streets? Is there room for them to stretch and grow? There are places on Commonwealth Avenue where the trees have better accommodations. They are in long raised planters, fancily edged in stone, with other plants. Those appear in front of important buildings like the business school and the gym, but ordinary classroom buildings get sticks in grates.

We know this isn’t good for either trees or people. We need nature — our souls need it, our lungs need it. Concrete and asphalt lead to flooding when it rains, overheating when the sun shines on the streets in summer. But everywhere I go, on those city streets, I see places where we could put little pockets of green — places where no one walks, empty useless concrete corners that could be something else. There could be plants, there could be green to rest and refresh our eyes, to cool the air and do all the other good things plants do. We could, if we wanted to, have little parks everywhere. What I’m saying here is that we should have those little parks, that our cities could be very different than they are now, that they could be gardens as well as cities — and they should. This would of course be more expensive, because people would need to create and take care of those little gardens. We could think of a word for that — I don’t know, something like “jobs.” It would create more jobs.

I dream of a world where cities have little green pockets everywhere we can put them, like a great dress with little pockets sewn all over it, holding plants. I dream of a city with birds and insects, a city that is slower, more human. I can imagine a hundred arguments against this, all having to do with economics, with practicality, and I will say: human ingenuity has done a lot more than this. Putting little parks in cities is one of the easier things we have done. Look at those glittering skyscrapers — you’re going to tell me my plan is harder than that?

I want little green pockets everywhere, to carry our hopes and dreams.

(The image is Avenue of Schloss Kammer Park by Gustav Klimt.)

January 22, 2023

Organizing My Closet

I got back from Budapest and immediately started to prepare for teaching at Boston University this semester. I’m teaching a class I really enjoy — a class on rhetoric to freshmen, not classical rhetoric as defined by Aristotle and the ancient Greek rhetoricians, but a broader, more modern rhetoric, focused on oral, written, and visual communication. We get to talk about traditional oral storytelling, the development of the reflective essay, modern modes of communication such as photography and film . . . It’s going to be a lot of fun, certainly for me and I hope for the students.

But the last few weeks have been too much transition, in too short a time. Last week I found myself feeling as though I did not know where I was, or even who I was exactly. I’ve traveled in the past without this sense of instability, but that was travel — I was going somewhere, with my life temporarily packed into a suitcase, and then I would come back. There was a here, a there, a me at home and a me traveling. This time there was a me at home in Budapest, then a me at home here in Boston. I was teaching in a new program, my daughter was moving back into the dormitory for her second semester of college. Nothing was fundamentally changing (I was still teaching at the university, still in the same apartment in Boston), and yet everything felt different. It felt as though the ground was shifting under me.

So I did the logical thing. I organized my closet.

I had all my Boston clothes in two closets and a chest of drawers in two different rooms, which meant I was always walking back and forth, trying to remember what fit with what else, what matched with what. The shirts and skirts were in one room, the sweaters were in another, so I would find myself standing in front of one closet thinking, What sweater goes with this skirt? and then maybe taking the skirt over to the other room, to check. I could not trust my memory, partly because I was jetlagged, partly because I might be remembering a sweater that was in another closet altogether, in Budapest. Anyway, I don’t carry my sweaters around in my head — that’s what the closet is for.

The first step was putting away all the summer and spring clothes. There’s snow on the ground, but when I pulled out one drawer, I would see short-sleeved shirts, and part of one closet was half filled with floral summer dresses. In my jetlagged state, I would spend a minute staring at them before thinking, No, winter dresses. What is the temperature again? Cold, rainy or snowy — that’s January in Boston. So I bought some storage boxes at the local hardware store and put away the clothes for warmer weather. My closets are not deep, but my ceiling is high, and there is a quite lot of space to go up — space that is usually wasted, but perfect for stacked storage boxes.

Then I organized the clothes that were left, the fall and winter clothes I will actually be wearing until spring comes again, which around here could be April, who knows. I put everything I actually use in two places, the larger closet and the chest of drawers. The other closet will be for my daughter, when she is here rather than in the dormitory. I used hanging shelves for the sweaters, so now they are right next to the skirts, and I can see immediately what goes with what else. Shoes are below, except the heeled shoes, which are on a rack above, and winter boots, which are in the coat closet below the coats.

I know, I know, that’s a lot of detail you didn’t necessarily need to hear about. But the process of putting my closet together was also a process of creating the place I live in, which was also a process of recreating myself. We don’t simply exist. We exist in relation to places and people — we interexist, so that my existence in Budapest is defined in part by the table where I do my Hungarian homework, the convenience store around the corner where I buy rétes. I am a person who eats rétes, a person who does studies Hungarian. Here in Boston, I was jetlagged and feeling a sense of vertiginous displacement, so I tried to define where I was in relation to something — the season, at a minimum. It’s winter, I will put away the summer clothes.

To be honest, I got a bit obsessive about it. I spent a day going through all my clothes, checking to see what I had, making sure it still fit and sparked joy (yes, that is a Mari Kondo reference), unfolding and refolding, going to the hardware store for more storage boxes, scrolling through the Ikea website for drawer dividers. At certain points, I felt pretty silly. But at the end, as I grew reflective, I thought the following:

Home is something we make, not just someplace we are. For most of the year, my home had been in Budapest. I had made that home, with a lot of help from a lot of wonderful people (especially during the renovations the year before). Over time, it had become a warm, welcoming, comfortable place. And it was mine, my very own apartment with a view of the Nemzeti Múzeum. Now I was back in Boston, in a rented apartment. I had to make it home again, at least for a while.

I started with a closet — probably, I’m not sure but it seems likely — because clothes define who we are. They demarcate different aspects of our lives, different roles we fill in relation to others. There are outdoor clothes and indoor clothes. In my case, there are teacher clothes — after a semester of not teaching, I had to think of skirts and sweaters that matched, of dresses that looked professional but did not prevent me from writing on a chalkboard. I had to become Dr. Goss again, and that meant dressing the part.

I’m so busy this semester — I have so much to do, mostly for other people (my colleagues, my students, my daughter) — that I wanted to make my own life as easy and intuitive as possible. I wanted to be able to move through my own apartment with a sense of fluidity and grace. I wanted, at a minimum, to be able to find the clothes I could wear (for a Boston winter) in one closet, one chest of drawers. So I could devote the time I had to other things — creating lesson plans, writing stories, watching Netflix with my favorite college student when she has a free night.

And finally, that I, at least, need a sense of order and routine in my life. Not just to function well, but in an existential sense. Because part of me knows, always and every moment, that we are on a small planet hurtling through space, so the solidity of the ground under our feet is always an illusion, and we are here for such a short time, like flames that spark up and then flicker out. Every moment of this precious life, every breath we take, is an improbable gift. We are always, every moment, in transition. But if I thought like that on average, ordinary days, I would probably go mad, like the heroine of an Edgar Allen Poe short story. So the existential anxiety has to stay below the surface. On the surface, I have to live my life, with intention and meaning — I have to create intention and meaning, a sense of solidity and continuity.

I think we all do this, every day. We create the solidity and continuity of our lives through our thoughts and beliefs, our actions. Anyway, that’s why I organized my closet.

(The image is Interior in Strandgade, Sunlight on the Floor by Vilhelm Hammershoi. This is a woman who has organized her closet.)