Theodora Goss's Blog, page 68

February 13, 2011

The School Itself

Tonight I am so tired that I can't write. So I'm going to let Thea write for me. She's been visiting for a while, and we've been having long conversations about all sorts of things. She's been telling me about her adventures, which are much more amusing than mine. Tonight I asked her for some information on Miss Lavender's School. And she told me – well, I'll just let her write it herself. While I have some dinner . . .

All right then. You wanted to know what it was like to go to Miss Lavender's School? I'll describe it for you. And you have to remember that, all the time Matilda, Emma, Mouse, and I were sneaking out at night, sneaking out during the day, traveling through time, all that – we were still going to classes, still doing our homework. That first semester, I got all Bs. But at least they weren't Cs, you know?

If you were going to Miss Lavender's, you would start at the Boston Common. One of the streets along the Common, and no, I'm not going to tell you which, has a small wrought iron gate. It's between two houses, and if you can't find it, you have to ask the cats. There are always one or two cats hanging around there. But they'll only tell you the way if you're the right person, the one who was admitted, who has an invitation, a reason to be there.

Open the gate and go down the lane that runs between the houses. (All the houses around the common are old brownstones. The lane is narrow, nothing but brick walls on both sides, with strips of some plant that lives in shade on both sides of the lane – liatris, someone once told me. And ivy growing up the walls.) It's called Hecate Lane, and once you get to the end of it, you get a surprise, because what you see there couldn't possibly exist. It's almost like a park, with a large stone house in the center. That's Miss Lavender's. It occupies more space than you would think existed there. Miss Gray explained how it worked to me once, but I've forgotten.

"It's magic, right?" I asked her.

"It's physics, and when will I get it through you girls' heads that magic is simply another word for science? That's why we call them the Magical Sciences."

That's what she says, but I still don't get it. And yet there it is, a park with a stone house in the middle, and gardens with paths, and playing fields. And a pond where we used to go sailing.

The school itself is two hundred years old – I mean this particular building, of course. Miss Lavender's has existed for who knows how many years. Thousands, I think. So don't expect modern comforts. The sinks are old and porcelain, the bathtubs are old and porcelain and take forever to fill, although they're great for reading once you've gotten in them, and the water is blazing hot. There are not enough showers, not for almost a hundred girls. We all eat together in the dining room, with the old school silver. The food isn't bad, lots of stews and the sorts of dishes that aren't too difficult to make, that girls will eat. We used to complain about it of course, claim that it was stewed cat. As though any cat at Miss Lavender's would allow itself to be made into stew! Most of them are too snobby to even talk to us. Most of them have already chosen their witches, and they spend most of their time with the juniors and seniors, doing whatever it is they do. By that point they can do all sorts of things we can't, or couldn't at the time I'm writing about. Teleport, travel through time, go to the Other Country whenever they wanted.

We were still taking our elementary classes. There are the regular teachers who are there all the time, or almost all the time, because you know Miss Gray travels around. Mrs. Moth, Miss Gray, Hyacinth. Miss Lavender teaches classes too, although she runs the school, which takes a lot of her time. And then each semester we would have visiting teachers. The Gentleman was there one semester – he was the best fencing coach we ever had. Morgan was there teaching Spellcasting. Merlin came once, not while we were there, but before. That was not such a great idea. I mean, almost a hundred teenage girls – and Merlin. Some of them had pictures of him up on their walls. And famous alumna would come to give lectures. Once, Athena Mandragora talked about advising the president on magical affairs.

So what would you do on a typical day at Miss Lavender's? Well, you'd get up at seven, when the bell rang. You'd get ready for the day, fighting for sink or shower space with the other girls. Breakfast in the dining room (oatmeal, pancakes, whatever the cooks had prepared that day). Morning class, Elementary Teleportation with Miss Gray for example, with fifteen other girls all trying to move oranges with their minds. She would show us how she could move just the orange seeds out of the oranges. Show-off. Then lunch, and some time to study or wander around the grounds. Or sit in the library, toward the back between the shelves, talking with Matilda, Emma, and Mouse about how we were going to sneak out and talk to Anatolia Mandragora. Then afternoon class, probably Magical History with Hyacinth. "Which witch was Queen Elizabeth's personal adviser during the second half of her reign?" she would ask. Of course only Emma knew the answer.

Then study time, when we actually had to study, because Magical History had made us realize that we were all a chapter behind. "How could you get behind? Honestly," said Emma. "Didn't you look at the syllabus? Do I have to explain the whole Tudor succession to you?" We solemnly assured her that yes, she did. Then dinner, some more time to plot and plan our sneak-out-ery, and bed.

"Tomorrow," I said. "It's Saturday, and if we go in the middle of the archery match, we won't be missed."

Four girls, four wooden beds that had probably stood in that room for a hundred years, pictures we had put up on the walls. Four desks with chairs, with names like Zephirine and Amalia carved into them with penknives. I suppose Miss Lavender's was like any other boarding school, really. Well, except for the flying, and the cats, and the saving the world.

February 12, 2011

Being Real

Once upon a time, I read the newspaper a lot more than I do now. I read it online, because it was free and convenient. What I mostly read was the New York Times. I still read the New York Times, at least selectively – the articles I'm really interested in. But I find that what I read, more and more often, are my friends' blogs. When I'm on my computer, to the left of my screen I have a list of my favorite blogs, and when I want to know what's going on, I check them. Or I check facebook. Or twitter. It's almost as though I've constructed a newspaper of my own, the sort of newspaper that used to exist in a small town, filled with local events and personalities. I live in an online community, and I check the news for that community. I'm still connected to the larger world, but in addition to hearing about what's happening in that world, I'm hearing who finished a story, who sold one, who has a novel deal. I like that a lot. It makes me feel as though I actually were living in a small town, where the local events matter. It makes me feel comfortable. In a way, it makes the larger world a bit less overwhelming.

I write all this to explain why I was reading a blog post by Neil Gaiman called Now We are TEN, about the fact that his blog is ten years old. (Only ten? Goodness. I think of it as having been around forever. In a way, my own blog has been around for almost as long. I uploaded my first website, and a fairly rudimentary website it was, back in 2001, when I was at the Clarion Writing Workshop. I still remember the first few emails I received – my first contact with readers! Including a soldier who was overseas, and who liked what I had uploaded. Shortly after that I started an online journal – back then, all hand coded in HTML, with no commenting, no RSS feed. But even then, a number of people would come and visit regularly.

What I noticed in particular about Neil Gaiman's post is that he included a picture of himself in pajamas, before he had showered and shaved.

And I thought, what an interesting choice. Why would he do that? Because we're all vain creatures, we all want to present ourselves to the world in a certain way. And there are plenty of pictures of him online that present him as a sort of literary rock star: the dark, brooding, handsome type. It's fun to have pictures like that taken of you. It's fun to play with your image, especially to present yourself as the glamorous author. And if you can, why not? We should be able to play with our images, to invent and reinvent ourselves.

I think the pajama picture comes from a different impulse, an impulse to be real. Because there is a point at which, as a writer, you become not quite real to people. We see this in the dead and famous: we know that Virginia Woolf was real, an actual person. And yet she is not real to us anymore, she is Woolf. They are Hemingway and Faulkner and Joyce, not people who ate breakfast and couldn't get songs out of their heads and had colds. That's all right, with the dead.

But at some point, living writers become unreal as well. To me, the writers I read as a teenager, and who affected me at that time in my life, will always be more than themselves, slightly mythological. I will never be able to look at Tanith Lee or Ursula Le Guin or Terri Windling or Patricia McKillip or Robin McKinley or Ellen Datlow or Jane Yolen as just people. Even though I've actually met some of them, and know a few of them well. They became important figures for me at a particular time in my life, and they still retain that magical aura.

Once, I almost met Ursula Le Guin. It was at Wiscon. I was standing in the women's bathroom, washing my hands in the sink, when I suddenly became aware that at the sink next to me was Ursula Le Guin. Did I introduce myself, say "I grew up on your books, they made me what I am? They made me a writer?" Of course not. Can you imagine Ursula Le Guin remembering you as the person who accosted her in the women's bathroom at Wiscon? And so I have never met her. Friends of mine know her well and have studied with her, and when they talk about her, it's as though they're talking about a real person. And intellectually, I recognize that she is. But my instincts tell me otherwise.

And I've noticed, and this is in the smallest possible way, that sometimes, when I meet someone who has read my stories but does not know me personally, I'm not entirely real either. I still remember the strangeness, one day, of being in the Boston University Barnes and Noble and having someone say, "Excuse me, are you Theodora Goss?" Someone who knew me only from my writing, who had seen my picture online. (This is the only time such a thing has happened to me, and I don't expect it to happen again anytime soon.) And it's still strange to hear myself referred to, not as Dora, but as Goss.

So I think we have an impulse, as writers, to insist on our own reality, to resist the mythologizing that does happen. We do that, in this technological age, by reaching out, by writing blogs, putting our selves (as real as we can make them) out there. A writer like Neil Gaiman gets mythologized more than most. I think the pajama picture represents an impulse toward the real, toward that sort of connection.

When I saw it, I thought, all right. I'm going to take a picture of myself, in my pajamas, before I've showered. The way I read emails first thing in the morning. Here it is:

For vanity's sake, I'm also going to include a picture of me several hours later, looking considerably more composed, as he does. Here I am answering emails:

It's a strange thing, this being not quite real. I think all writers have to deal with it. I see my friends dealing with it, since many of them are in the process of becoming known, becoming personalities. It's wonderful in a way, because it means that people are thinking of you as a writer, appreciating your work. But it's also a thing to manage, a thing that can make you feel quite strange about yourself, as though you're not really you. Which you are – at least first thing in the morning, in pajamas.

February 11, 2011

Leonora Grimsby

(Just a note before I begin. I was so tired today! All day long it was twenty degrees or below, and there were problems with the commute, and when I finally got home, I didn't even feel like writing. But then I saw how many people had come to this website, and suddenly I felt better and as though it was all worthwhile, because I was writing essays or stories and you were reading them. And you know, for me that's the whole point. So thank you. We now return to our regularly scheduled programming. But I just wanted you to know that . . .)

The next morning, our conversation went something like this.

Emma: I still think we should tell Mrs. Moth.

Matilda: No. Aunt Matilda is my aunt, and she's a nasty old witch, but we're still going to rescue her. Without getting kicked out of school.

Thea: You wouldn't use the word "witch" in that way if you'd grown up with witches.

Matilda: Well, I didn't. All right?

Mouse: I think we have a couple of clues. We should look at the clues.

Thea: I agree. Let's focus on the clues. What clues are you talking about?

Emma: Miss Lavender's. That woman said they went to school together, and that Mrs. Tillinghast did something to her. With her friends.

We were sitting in our room, before classes. Your first year at Miss Lavender's, you pretty much all take the same classes. That morning we had Elementary Teleportation with Miss Gray. Then lunch, then Spells and Incantations with Hyacinth, then a Magical History study session in the library.

"The Yearbooks," I said. "We need to look at the Yearbooks."

The Yearbooks were on shelves in the hallway by Mrs. Moth's office. There were years and years of them, all the way back to when books were first produced, I guess. And even before, because the earliest ones were just scrolls with names on them. They took up the entire hallway, all the way down to the teachers' parlor.

"We have half an hour before class," said Emma. "Let's go look! I'm so curious."

But when we got there, to the hallway with those long shelves, we looked at one another with dismay.

"Where do we start?" asked Matilda. "I mean, there have to be a thousand books here."

"Several thousand," said Mrs. Moth. We all turned around, startled. She was standing behind us. Where had she come from?

"Oh, we're just looking for the book with Matilda's aunt in it, Mrs. Moth," said Emma. The useful thing about Emma is that she always sounds so respectful and polite. She never sounds as though she could be doing anything dangerous or forbidden.

"That's this one right here," said Mrs. Moth, pulling out a dusty old volume. It was bound in leather, and had gilding on the spine. It said, Miss Lavender's School 1963.

"Would you mind if we borrowed it for a while?" asked Emma.

"Not at all, girls," said Mrs. Moth. "I'm glad to see that you're interested in school history."

Which sounded all right. I mean, it sounded as though she believed us. But as we were going back toward the students' parlor, I looked back at her. There was an expression on her face – but maybe I was misinterpreting it, I don't know.

Anyway, there was no one in the students' parlor (all the other girls were either still at breakfast or up in their rooms), so we sat on the rug by the fireplace. There was a fire going, because even though it was only September, the mornings were already chilly. We flipped through the Yearbook.

"Can you believe anyone ever did their hair like that?" said Emma.

"Our uniforms look exactly the same," said Mouse. And they were: the purple skirts, white blouses, and purple jackets or cardigans with Miss Lavender's School embroidered on a front pocket. It didn't allow for a lot of individuality.

"Look, there!" said Matilda. And there she was, Matilda Tillinghast. Captain of the Flying Club, on the Magical Sciences team, and a Junior Pattern-Keeper.

"No, look there," said Mouse. "That's her." Each of the girls had two pages of their own, with their photographs, activities, sayings they had chosen (and pretty sappy some of them were, I thought). Mouse was pointing to a photograph of four girls together, all in their sports clothes, all holding broomsticks. Underneath, the caption read, "Me, Em, Leo, Tollie. The best roommates ever!"

"That's her," said Mouse again. "Leo. Who do you think she is?"

Quickly, because we only had ten minutes before class, I flipped through the pages. "There she is again. Leonora Grimsby. What about the other two?"

"Well, I can tell you who one of them is," said Emma. We all looked at her. How did she know? "It's just – the one called Em? That's Mom."

"What, your Mom?" said Matilda. "Seriously?"

"Yes, seriously. Her name is Emmaline, like me. She was Matilda's roommate here at Miss Lavender's. They used to get together once every couple of months, with the other one – Tollie. Anatolia. She's one of the Mandragoras."

"So, let me get this straight," I said. "There were four roommates, just like us: Matilda Tillinghast, Emmaline Gaunt, Anatolia Mandragora, and the one we saw at Tillinghast House – Leonora Grimsby. And the other three did something to her. Emma, why didn't you tell us that your Mom was Aunt Matilda's roommate?"

"Well, I didn't want you all going and talking to her. And I didn't think it was that important. I mean, that woman – Lenora – she just said friends. She didn't say roommates."

"It was Sitgreaves who said friends," said Thea. At the mention of his name, Mouse flinched.

"Mom told me that something had happened at school," said Emma. "But she never told me what, and I never connected it with any of this stuff. Until now."

"What did she tell you?" asked Matilda.

"Just that a friend of hers had done something and gotten expelled, that's all. She told me that if I ever got into trouble at Miss Lavender's, she was going to – well, she never said what, exactly. But I bet it would be horrible. You don't know Mom when she's angry! Thea, don't look at me like that. I was the one who said that we should tell Mrs. Moth. But we're not talking to Mom."

"Well, we're going to have to talk to someone," said Mouse. "We know her name – Leonora Grimsby – but we still don't know what happened, or why she's so angry at the other girls. How do we find that out? Could we do some sort of spell?"

"I think we should just ask," said Matilda.

"No!" said Emma. "I told you, we're not talking to Mom."

"No, I think Matilda means the other one," said Thea. "Anatolia Mandragora. Where is she now?"

"Here in Boston," said Emma. "All right, we can talk to her. I don't think she would tell Mom – I don't think she would even remember or think it was important. She's kind of strange, thought."

"Strange how?" asked Matilda.

"I can't describe it," said Emma. "You'll see."

I've decided that every Friday, I'm going to write part of the Shadowlands serial. If you want to read parts that I've already written, go to Serial. There, you can read all about Thea Graves, Matilda Tillinghast, Emma Gaunt, and Mouse, from the beginning.

February 10, 2011

Convention Schedule

Here is my convention schedule for the next two months.

February 18th-20th, Boskone

I will be at Boskone from Friday afternoon to Sunday afternoon. Here are the panels and reading I will be doing:

Friday, 8 p.m., Welcome to Lovecraft's World

Theodora Goss

Jack M. Haringa

John Langan (M)

Charles Stross

Considering the worldview of New England's master of weirdness H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), fantasy writer Theodora Goss observes: "Lovecraft's universe has turned out to be the place we actually inhabit. He tells us that our world operates by laws we do not understand. That the universe is larger than we know, and older, and that it does not care about us. He tells us that we can lose our humanity more easily than we imagine." Discuss. (Cthulhu visual aids are optional.)

Saturday, 1 p.m., The Writer's Child

Katherine Crighton

Theodora Goss

Jo Walton (M)

Jane Yolen

What's it like for a writer to raise a kid? Our panel includes both writers and people who were (and are) writers' children. Are the writer's child-rearing methods, biases, or hopes different from those of other parents? How is a writer's child different from a reader's child? Stories will be told.

Saturday, 2 p.m., Writer vs. Copyeditor – Lovefest or Deathmatch?

Theodora Goss

Teresa Nielsen Hayden (M)

Jo Walton

Let's discuss process and roles, how copyeditors can help, when they can go too far, points of contention, and more. Red pens may be flourished, but let's hope not blood-red . . .

(Notice, by the way, that these first three panels are related to blog posts I wrote! I'm incredibly flattered to have given the Boskone scheduling folks some ideas.)

Saturday, 4 p.m., Fairy Tales into Fantasy

Greer Gilman

Theodora Goss (M)

Jack M. Haringa

Jane Yolen

A whole branch of fantasy literature is based on re-examining the assumptions of well-known fairy tales. Panelists discuss some of the best examples.

Sunday, 11 a.m., Mythpunk

Debra Doyle

Gregory Feeley

Greer Gilman

Theodora Goss

Michael Swanwick

Wikipedia says, "Described as a subgenre of mythic fiction, Catherynne M. Valente uses the term "mythpunk" to define a brand of speculative fiction which starts in folklore and myth and adds elements of postmodern fantastic techniques: urban fantasy, confessional poetry, nonlinear storytelling, linguistic calisthenics, worldbuilding, and academic fantasy. Writers whose works would fall under the mythpunk label are Valente, Ekaterina Sedia, Theodora Goss, and Sonya Taaffe." And what do WE say?

(Well, I've already said quite a lot about this one, I think. And hey, who's the moderator?)

Sunday, 1 p.m., A Child's Garden of Dystopias – the Boom in Nasty Worlds for Children

Bruce Coville

Theodora Goss

Jack M. Haringa (M)

Kelly Link

Why do dystopias and YA literature seem to go together? Are YA dystopias more common now than previously? Are there differences between YA and adult dystopias – perhaps a different ratio of cynicism to hope? How does "if this goes on" fit in?

Sunday, 2:30 p.m., Reading: Theodora Goss (0.5 hrs)

Theodora Goss

(This is late in the day on Sunday, and I'm not sure anyone's going to come. So come to my reading? And what would you like me to read? Any ideas?)

March 17th-19th, International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts

I believe I'm reading at this time:

Friday, March 18, 8:30‐10:00 a.m.

With the wonderful James Patrick Kelly and Rachel Swirsky.

(I had to ask for a last-minute change because of my flight schedule, but I think that's the right time. Again, what should I read? I think that for the academics, I should read something from "Pug." If I can't read them a Jane Austen time travel story, who can I read it to?)

I'm particularly looking forward to ICFA because it's going to be in Orlando, Florida, and I've already bought summer dresses to bring with me. And a swimsuit.

I know, I know, I'm supposed to be totally focused on professional networking and development. But it was below freezing here in Boston today. If I network, it's going to be at the poolside bar. If there's a poolside bar. All I can say is, there had better be.

(And there had better be umbrellas in the drinks, too. How can you have an academic conference without them?)

February 9, 2011

Researching Fairies

What was wrong with me yesterday?

Whatever it was, I'm clearly not right yet. I'm still completely exhausted.

The problem with writing is that, like any other intense activity, it requires focus, concentration. And I just don't seem to have that right now. And my throat hurts. I think I'm sick, honestly.

I woke up this morning and, although I knew it was going to be below freezing today, I just couldn't face wearing the same old jeans or corduroys again. So I wore one of the skirts I wrote about yesterday, which looked like this:

At the university, I went to the library and picked up two books on fairies, The Fairies in Tradition and Literature and An Encyclopedia of Fairies by Katherine Briggs. I read the first one and took notes, then taught my classes, then came home and read the first one again, taking notes until I fell asleep. Not actually on top of the book, but pretty close.

When I woke up, I sat down to write this post. But my head doesn't feel particularly clear, and as I said, my throat hurts. I think the season of being sick is upon us.

This is the place in my research process where I just read for a while, where I start to get a feel for my subject. What I'm looking for at this point is some way of approaching it, some point of view. Also some way of dividing it up. Do I write about fairies by looking at them historically: folklore fairies, literary fairies in their various centuries? Do I write about the characteristics of fairies, their interactions with humans, fairy poetry, fairy paintings? I'm still trying to decide.

What I do know, already, is that there's an awful lot of information out there.

One thing that surprises me is how many people claim to have seen fairies in one form or another. Add that to the people who claim to have seen ghosts, or to have had other sorts of supernatural experiences, and what do you get? I mean, it's so easy to discount things like that, to say there's no scientific validity to them. But what are they really? Our brains tricking us? Or something genuinely strange about our world that we're interpreting in the ways we know how, as ghosts or fairies? What shape is reality, I guess is what I'm asking. And I ask this as a fantasy writer, meaning that I need to know reality in order to bend it, or break it, or otherwise shape it anew.

I did read something in one of Briggs' books that started me thinking about story ideas. It was an excerpt from Ancient Legends of Ireland by Lady Wilde, Oscar's mother, about the Banshee:

"But only certain families of historic lineage, or persons gifted with music and song, are attended by this spirit; for music and poetry are fairy gifts, and the possessors of them show kinship to the spirit race – therefore they are watched over by the spirit of life, which is prophesy and inspiration; and by the spirit of doom, which is the revealer of the secrets of death.

"Sometimes the Banshee assumes the form of some sweet singing virgin of the family who died young, and has been given the mission by the invisible powers to become the harbinger of coming doom to her mortal kindred. Or she may be seen as a shrouded woman, crouched beneath the trees, lamenting with a veiled face; or flying past in the moonlight, crying bitterly; and the cry of this spirit is mournful beyond all other sounds on earth, and betokens certain death to some member of the family wherever it is heard in the silence of the night."

For some reason, it reminds me of a story by H.H. Munro called "The Wolves of Cernogratz." A wealthy family has moved into the von Cernogratz castle. They are told that if someone dies in the castle, the wolves will howl for them, and the Baroness says that is not true, a relative died in the castle recently and no wolves howled. The faded old governess speaks up and says that the wolves will not howl for just anyone, only for a member of the von Cernogratz family. She says that she herself is one of the von Cernogratz. She is not believed, is thought to be claiming an ancestry that does not belong to her. But several weeks later she becomes sick, begins dying. And the wolves begin howling.

"Not for much money would I have such death-music," says the Baroness.

"That music is not to be bought for any amount of money," says one of her relatives.

The governess dies, listening to the howling of the wolves.

My story would not be like that. I would focus on "persons gifted with music and song," because I'm interested not in hereditary aristocracy, but in the aristocracy of creators, of people who are gifted with artistic talent and use it. But it would be about who the Banshee wails for, who deserves to have that sort of warning.

I have other work to do tonight, this being February as I said some time ago – the difficult month. But writing my Folkroots column teaches me so much. If you're going to be a writer, I highly recommend writing non-ficton – in some form.

February 8, 2011

The Haul

I'm so sorry.

It's the sort of day when I have absolutely no thoughts, nothing at all to say.

I haven't had a chance to work on the Folkroots article, so I can't write about that. And I have nothing at all to say about writing, not today. All I've done today is work on projects that wouldn't interest you. (Trust me.)

The only thing I have to write about today is the haul I made at Goodwill. This was the Goodwill on Commonwealth Avenue, the Goodwill of all Goodwills. The Platonic Goodwill.

So I'm going to post some more pictures of my finds.

I found two baskets. This is the first of them, and it's filled with the dishes I bought, which were all my favorite cream-colored ironstone. I just buy a lot of ironstone, and it all sort of mixes together, you know? These are Johnson Brothers and Adams.

This is the Adams, this adorable little sugar container. No lid, but I don't think that matters, because I'm probably going to use it for flowers anyway.

This is the second basket, with some silver plate I found. Here it's all tarnished.

But as you see, it cleans up quite nicely. (Although it needs more cleaning. Silver never really stays nice until you use it regularly.)

And I bought a dress and four skirts, each of which actually fits. No alterations necessary, thank goodness.

I would be a little depressed about the summer skirts, because it's going to be so long until summer. But in March, I'm going to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts in Orlando, and I'm going to need summer skirts there. So I'm excited.

It's been a long day, and I'm tired. But at least I brought some beautiful things into my life, and that's always worthwhile.

February 7, 2011

Writing Fairies

It's funny how publishing works. My first Folkroots column hasn't come out yet, and here I am working on my third. My first one was about the femme fatale, my second one was about vampires, so I thought that for the third one I would focus on something lighter, more traditional fantasy fare. I chose fairies.

I have to write as much of the column as I can this week, since the next few weeks will be particularly busy for me. I thought you might be interested in the process, so I'll be posting about writing the column as I write it. Today I thought I would post about how I begin.

I actually begin with the art.

I've chosen the art to include with the column, and of course I'm not going to post what I chose here. You'll have to wait for the column, for that. But I will post some pictures that I decided not to include, and why.

The first picture I chose not to include was Titania and Bottom, by Henry Fuseli. It's a beautiful painting, but rather dark. And I'm not sure I want to focus on particular fairies in the pictures, although I suspect that I'll write about Titania and the Shakespearian fairies in the column itself.

The second picture I chose not to include was The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke, by Richard Dadd. It's just too busy. It's not going to reproduce well in a magazine, particularly since it's going to be smaller than this size. Online that wouldn't be such a problem, because you could click on it and look at the details. But that's not possible in a magazine, of course.

The third picture I chose not to include is La Belle Dame sans Merci, by John William Waterhouse. I wrote about the Belle Dame in my column on the femme fatale, and don't want to use her image again so soon, even though the image I chose last time was a different one.

At least, I think I won't be including those. I could still change my mind.

The second step is to locate my sources. Of course I started with the university library database. And I found some books that look useful and interesting, one on Elizabethan fairies and one on Victorian fairies. (Isn't it interesting that both focus on eras named for queens? I wonder if fairies tend to become more prominent in eras when queens are ruling.) But in this instances, I knew that I would also find some sources online, because I knew there must be articles on fairies on the Journal of Mythic Arts website. And sure enough, I found two wonderful articles on fairies by Terri Windling:

Fairies in Legend, Lore, and Literature

and

I know those articles are going to help me figure out what I want to focus on, because this article can't be longer than 5000 words. And anything Terri wrote, I know is thoroughly researched and reliable. I also want to make sure I know what Terri has written, because I don't want to simply reproduce her work with my own research. I want to be able to offer my own interpretation of fairies, and then also tell readers where to find hers.

I have two more library books to look at, and a stack of my own books that will have information on fairies, including W.B. Yeats' book on Irish fairy and folk tales. The problem with fairies is that there's actually too much information out there. I'll have to narrow it down first, figure out what is most important to look at. I think looking at Terri's articles will help me do that, so I'll start there.

I learn so much from writing these columns, and get so many story ideas. That makes all the work worthwhile.

February 6, 2011

A Beautiful Life

There are some blogs I love to read just because they're so beautifully put together. Three of my favorites are Terri Windling's The Drawing Board, Rima Staines' The Hermitage, and Jen Parrish's blog for Parrish Relics Jewelry. Somehow, I came across an old blog post of Jen's, "Treasures Found," on going to Sister Thrift, one of her favorite thrift stores in Burlington, Massachusetts. And I thought, wait a minute! I live a short drive away from Burlington. So I looked up Sister Thrift on Google Maps, and away I drove through the snowy landscape. I love thrift stores. Partly because I genuinely am thrifty, although I'll spend a great deal of money on things I believe are important, like going to conventions. And partly because I think shopping is boring unless you turn it into a game.

Here's the game: be elegant while spending as little money as possible. The game is not to spend as little money as possible. You also have to be elegant. That's crucial, otherwise it's no fun. So I'm going to show you some of the things I bought at Sister Thrift, and you can decide for yourself whether they were elegant enough to justify the cost.

First, I bought a small evening purse. I'm going to show you all of these items as they were processed once I brought them home. Here is the purse being washed in the sink:

And hung to dry:

And here it is all dry:

I think it's going to look nice with a black evening dress. The second item I bought was a pillow. Here is the pillow being washed:

And here it is all dry and on a bed:

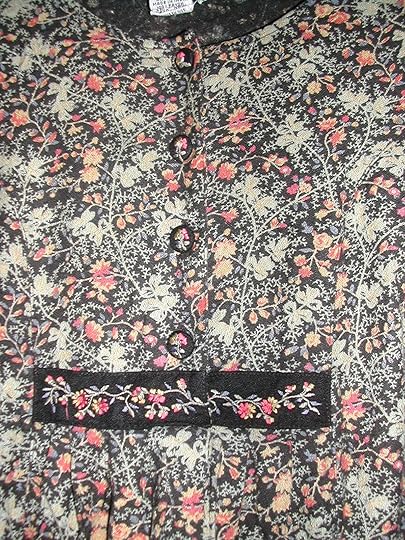

The third item was a dress from April Cornell. You know how expensive April Cornell dresses are. Here it is being washed:

And here it is hung on a door, although a dress like this never really looks like anything hung on a door:

And here is a detail, because I love this embroidered strip and the embroidered buttons:

And here it is on me:

It comes down to about my calves, and I have no idea yet where I would wear it. But it's incredibly comfortable. And here is the final item I bought. It's a dress from The Gap. Being washed:

And hung on a door both with and without the sash:

And on me both with and without the sash:

I'm not actually sure I like the sash that much. And these pictures remind me that I need a haircut. Desperately.

But what I wanted to say today, inspired by Terri's, Rima's and Jen's blogs, is that even though my life is completely crazy right now, even though I barely have time for a quick trip to a thrift store or a haircut, I want my life to be beautiful. I want it to contain beautiful things, to be as elegant as I can make it. That doesn't involve spending a lot of money. If it did, people who were wealthy would have elegant houses. I've been in quite a lot of houses belonging to people who were wealthy, and almost none of them have been elegant. (Remember that I was a corporate lawyer in Manhattan and Boston. I went to a lot of cocktail parties.)

I think that's part of being a writer too, creating a space for yourself where you can be happy, where you can look around and see comfortable, beautiful things. And wear comfortable, beautiful clothes. I think it's important to surround yourself with things you truly love.

That's what I mean by a beautiful life.

Oh, and by the way, those four items? Cost just under $15.

February 5, 2011

Love and Squalor

I've been writing about all sorts of things related to writing. I thought I'd better write about writing itself.

The title of this post comes from the J.D. Salinger short story "For Esmé – with Love and Squalor."

Have you read it? It's one of his most famous short stories. It's told by a soldier who is training in England, in World War II. One day he walks into a church and listens to a children's choir practicing. He notices the best singer, a girl. Later, he is sitting in a tearoom when she, her brother, and her nurse walk in. (I'm doing this from memory, so correct me if I make any mistakes.)

Her name is Esmé, her brother's name is Charles. She is a self-possessed young lady with a vocabulary that is not quite under her control – she uses words that don't quite mean what she things they mean in an effort to be sophisticated. But she's charming, an attractive character. Her brother, who is younger, is a typical little boy. Their nurse tries to get them away from the soldier, but they pay no attention to her. Their father has died in the war, their mother is somewhere, I don't remember where. But it's obvious that Esmé is used to giving orders and looking after Charles. When Esmé learns that the solider is a writer, she asks him to write her a story. She asks him to put a lot of squalor into it. It's obvious that she doesn't quite understand the word. Before she and Charles leave with their nurse, she asks the soldier for his address so she can write to him.

The scene shifts, and the solider who is narrating the story tells us that this is the part with the squalor in it. The war has ended. It's obvious that there's something deeply wrong with the soldier, that he's seen terrible things. But he finds a letter from Esmé, a letter that has taken a long time to reach him. Reading that letter is almost like reading a letter from another world, where there are still children, and there is still innocence, and there is still a future. And it saves him – suddenly, instead of the terrible insomnia he's been feeling, he feels sleepy. And you know that he's going to be all right.

It's a wonderfully written story, strong and clear. And my point today is that without that, without the wonderful writing, none of the rest of it matters.

If you're a writer, your first duty, a duty you owe to yourself and your readers, and to your writing itself, is to become wonderful. To become the best writer you can possibly be.

Now that I've written that, I feel obligated to suggest some ways to actually do it, to become a wonderful writer. I think everyone becomes a wonderful writer differently. But here, at least, are some ideas.

1. Read a lot. But read as a writer, to see how other writers are doing it. And make your knowledge of literature in English as deep and broad as you can. In workshops, writers are often told to read what is being written now, but if that is all you read, you are limiting yourself. You need to get a good overall sense of English literary history, so you can writer out of that knowledge.

2. Learn as much as you can. Take every opportunity to learn about writing, whether it's through classes, workshops, whatever is available to you. This may be difficult, because things like classes, workshops, writing programs, require time and money. But I say this honestly and somewhat harshly – if you're not willing to prioritize your writing, perhaps you should do something else?

3. Write all the time. I believe in writing every day, at least a thousand words a day. We have a strange idea about writing: that it can be done, and done well, without a great deal of effort. Dancers practice every day, musicians practice every day, even when they are at the peak of their careers – especially then. Somehow, we don't take writing as seriously. But writing – writing wonderfully – takes just as much dedication.

4. Accept criticism. If you do not offer your work for criticism and accept that criticism, meaning give it serious thought and attention, then you will never improve.

5. Be ambitious. Try to be as good as you can, to improve your craft, to become a master of your art. Push yourself to be better, do not rest on what you have done before or what comes easily. If you tell a group of writers, and specifically science fiction and fantasy writers, that you want to be as good as Salinger, as Jane Austen, as Jorge Luis Borges, they may look at your strangely. I know, because I've gotten that look before. It's as though you've told them you're aiming too high, wanting too much. But why shouldn't you? Why shouldn't you take the best writers as your models? Why shouldn't you want to write as well as Virginia Woolf? With fairies.

I think what I've said can be encapsulated in four words:

Engage fully. Be relentless.

I write all this because there's so much information out there now about how writers can succeed. A great deal on marketing, social media, that sort of thing. And I do think all of that is important. I do.

But if the writing isn't wonderful, what's the point?

February 4, 2011

The Sitgreaves Murders

"See, I didn't grow up with witches," said Matilda.

We had walked back to Miss Lavender's in silence, through the silent, lamp-lit streets. Even the Common was deserted at that hour. We had opened the gate, which was left unlocked, and walked down Hecate Lane to the school grounds. Only a few lights were on, the one above the front door and what looked like a light in the kitchen.

We had not gone in. None of us had felt like going in yet. Instead, we had sat down on one of the garden benches.

Then Mouse had said, "I need to go for a walk." She had stood up, walked down one of the garden paths, and disappeared into the darkness.

After a few minutes, Emma had said "I'm not sure she should be alone right now," and followed her. That was the Gaunt in her. Gaunts do things like that. You see, a bunch of Gaunts had died in the Sitgreaves Murders. Figures that Emma would be the one to follow Mouse, to tell her it was all right. Even though it wasn't.

"An aunt of hers died, a couple of cousins, I'm not sure who else. Some Tillinghasts died too. One Graves. Hawthornes, they're an old New England witching family. Mandragoras. Grimms. A lot of people who aren't people, I mean who are from the Other Country."

"I thought people never died there," said Mathilda.

"Yes, that's why no one was prepared. My Mom was at that party, you know," I said. "She told me about it later. She said it was one of the worst things she had ever seen. Tree Women weeping sap. Morgan was there doing triage."

And then I told her about Sitgreaves.

"He was one of the most talented warlocks that Merlin ever trained. Samael Sitgreaves was his name, and the Sitgreaves back then were just like the Gaunts now. You know, rich and richer. But he did something terrible, and Merlin cast him out."

"What did he do?" asked Matilda.

"He fell in love with one of the White Women of the Forest, who wear white dresses and shoes of bark. But she did not love him back, so he kidnapped her. He hid her so well that no one could find her, and a year later she died in childbirth. He appeared one night on the doorsteps of Sitgreaves House and knocked on the door. The housekeeper answered, and he gave her the child, told her it was called Sophia, and then vanished. That was the last anyone saw of him, until the murders." I kicked at the grass with my shoe. My mother had told me this story, when she was still alive. Sometimes I loved to think about her, and sometimes I hated it.

"That must have been Mouse," said Matilda. "Why couldn't anyone find him? I mean, people like Mrs. Moth and Miss Gray . . ."

"I don't know," I said. "I just know they couldn't. He found a place to hide, and no one could trace him there."

"So what happened then? I mean, the murders."

When my mother had told me about it, she had cried. Her sister had died there, and another Graves, a distant cousin that she didn't know well. She had told me, "But I still remember that she was wearing a pair of bright red shoes, and a hat with red roses on it. It was supposed to have been such a wonderful day!"

It had been a birthday party for Alistair Gaunt, who was turning a hundred. And there were a hundred guests invited, to the party under the large tent in a field close to Mother Night's house. My mother remembered cakes shaped like winged horses, and fountains that bubbled with wines of different colors and flavors, and dragons that whirled through the air, sometimes knocking off the hats of guests. There was music, played by an odd assortment of instruments that moved by themselves.

In the middle of the festivities, suddenly, he was there. Samael Sitgreaves in a black suit, with a cape over his shoulders.

"Ladies and gentlemen and others," he said. "Don't be alarmed. I've simply come for what's mine." He meant Mouse. She was just a little girl then, two or three years old. The Sitgreaves had been looking after her. And they wouldn't give her to him.

His own mother said to him, "When you left that child in our keeping, you gave up any right you had to her. She is ours now, and you will not take her away from us."

And you know, everyone there, every Sitgreaves and Gaunt and Graves and Hawthorne and Mandragora and Grimm, stood ready to oppose him. But he waved his hand, and it was as though something was torn open, and then people were screaming. The dead lay dead, and the living tried to keep anyone else from dying, and Sitgreaves was gone – with Mouse.

"That's a terrible story," said Matilda. "What about people like Mrs. Moth and Miss Gray. Couldn't they do anything?"

"Well, they weren't there, for one thing," I said. "Morgan came when she heard the screaming, and tried to help. And afterward, Miss Gray searched for Mouse. She finally found her – she had been hidden in time. She brought her here, to Miss Lavender's, where she thought Mouse would be safe."

"You said the Sitgreaves were a rich witching family. Why can't they protect Mouse now?"

"Sitgreaves killed every last one of them. There are no Sitgreaves left anymore."

"Except me," said Mouse. She walked out of the darkness, and Emma walked after her. "I'm the last one."

"It's not your fault, you know," I said. "You were, like, two years old."

"I know that," she said. "But how would you feel having a murderer for a father?"

Emma put her arm around Mouse.

"Look," I said. "We can't do anything else tonight. Let's just go in and get to sleep. Tomorrow we have to talk about what to do. Because if Sitgreaves is back, and he's plotting in some way, then we have to do something."

"Why can't we just tell Mrs. Moth?" asked Emma.

"And what's she going to say then?" said Matilda. "She's going to ask us how we got this information, and then we're going to tell her, oh yeah, we forgot to mention it, but we sneaked out at night and broke into Tillinghast House, and then we're all going to be expelled!"

"No telling Mrs. Moth," I said. "But we have to do something, and we'll talk about it tomorrow. All right?"

They all nodded, although I could see Emma was reluctant. But after a quick raid on the kitchen for bread and cheese and grapes, we went to bed. I dreamed that night of the Sitgreaves Murders, the way my mother had described it – with the sudden flash, the clap as though of thunder, the tearing sound. And then the screaming. I woke in the middle of the night, in a sweat. But I fell asleep again soon after and slept without dreams, all night long.

I've decided that every Friday, I'm going to write part of the Shadowlands serial. If you want to read parts that I've already written, go to Serial. There, you can read all about Thea Graves, Matilda Tillinghast, Emma Gaunt, and Mouse, from the beginning.