Barbara Sjoholm's Blog

September 9, 2025

Britta Marakatt-Labba's Ancient Mother Statue on the Highline

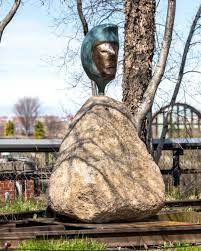

Urmodern, by Britta Marakatt-Labba

Urmodern, by Britta Marakatt-LabbaFor anyone in New York on Oct 7 at 12:30-1:30, the Sámi artist Britta Marakatt-Labba will be discussing her sculpture, Urmodern, located on the High Line between Gansevoort and Little West 12th Streets.

Many of us know Marakatt-Labba through her embroidered narratives of Sámi history and other two-dimensional work. Her reknown has only increased over the last years, with one-person shows at the National Gallery in Oslo (2024) and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm (2025), and she's also been represented in art exhibits in the U.S., in connection with other Arctic and Sámi artists.

I only recently heard that she has a sculpture on the Highline in New York, at least until March of 2026, and that it is meant to represent a female deity. Here's the text from the announcement for her talk:

"For the High Line, Marakatt-Labba presents Urmodern, which translates to “primordial mother.” Sámi mythology is based on the belief that every stone, plant, and body of water has its own spirit. It teaches that the cosmos and the earth were created and are protected by goddesses, emphasizing the pivotal role of women in Sámi culture. Through this lens, Urmodern serves as a representation of these female deities. The boulder-like base of the work is made of granite, topped with the head of the goddess rendered in bronze. Marakatt-Labba’s contribution to the High Line underscores the importance of environmental stewardship on a global stage, engaging audiences in critical dialogues about Indigenous rights and feminism."

September 7, 2025

Katarina Barruk at the BBC Proms

Katarina Barruk, 2025On August 31, 2025 Sámi vocal artist Katarina Barruk performedin concert with the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra at the BBC Proms festival atLondon's Royal Albert Hall. It was a history-making event, given that she wasthe first Sámi performer ever to participate in the Proms. I read about this inthe BarentsObserver, which has a link to a broadcast from Radio Sweden, where she’sinterviewed (in English). Barruk’s Sámi identity wasn’t the only thing notable aboutthe event. Barruk sings and joiks in the Ume Sámi language, which is consideredextinct in Norway and is severely endangered in Sweden. It was traditionallyspoken around the Ume River in central Sweden, around towns such as Sorsele, Lycksele,Arvidsjaur, and Storuman, where Katarina Barruk was raised. Her father, one ofonly a handful of people to still speak Ume Sámi, is a language consultant andteacher whose work involves documenting and rivitalizing thelanguage; in 2018 he published the first Ume Sámi-Swedish dictionary.

Katarina Barruk, 2025On August 31, 2025 Sámi vocal artist Katarina Barruk performedin concert with the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra at the BBC Proms festival atLondon's Royal Albert Hall. It was a history-making event, given that she wasthe first Sámi performer ever to participate in the Proms. I read about this inthe BarentsObserver, which has a link to a broadcast from Radio Sweden, where she’sinterviewed (in English). Barruk’s Sámi identity wasn’t the only thing notable aboutthe event. Barruk sings and joiks in the Ume Sámi language, which is consideredextinct in Norway and is severely endangered in Sweden. It was traditionallyspoken around the Ume River in central Sweden, around towns such as Sorsele, Lycksele,Arvidsjaur, and Storuman, where Katarina Barruk was raised. Her father, one ofonly a handful of people to still speak Ume Sámi, is a language consultant andteacher whose work involves documenting and rivitalizing thelanguage; in 2018 he published the first Ume Sámi-Swedish dictionary. Katarina Barruk herself has been a language-immersionteacher as well as a musician; now she mainly concentrates on her work as asinger, appearing internationally and releasing videos and singles. Like anotherSámi vocalist and activist, SaraAjnakk, who I’ve written about before on this blog and who did not grow upspeaking Ume Sámi but has painstakingly learned it and who writes many of hersongs in it, Barruk has become a spokesperson for Ume Sámi. Much of thecoverage of Barruk’s performance at the Proms mentioned the Ume language.

It wasn’t the first time that Ume Sámi was in the news in England—Iwas able to find an article in the Guardian from 2014, “Reindeerherders, an app and the fight to save a language,” which gives a goodoverview of the language and the efforts to revitalize it. In the article, Katarinais mentioned as a “young, passionate advocate for access to language education,”who is “currently recording her first album using Ume Sami lyrics andinfluences from the traditional Sami Yoik.”

August 25, 2025

Sámi Connections with Polar Expeditions

It’s been very warm here on theOlympic Peninsula in the Pacific Northwest the last week. Not compared to Phoenix,of course, but high for those of us more used to summer temperatures in the sixtiesand low seventies. The heat encourages me to continue on with polar themes.

Recently,for my travel book North Coast of the North, about Arctic Norway, I’vebeen doing some research into a handful of Sámi from Northern Norway whoaccompanied some of the famous polar explorers on expeditions to Svalbard, Greenlandand Antarctic. A good source has been the website, Polar History, sponsored by the Polar Institute and the Arctic University in Tromsø.

Along withbiographies of over two hundred men, including six Sámi, is a separate category listing twenty-eightwomen who had a connection to one or both of the poles, whether as cook, wife,hunter, scientist, or explorer. One woman appears in both categories.

Margarthe KittiThis is Margarthe(Lango) Kitti. As a young girl from a reindeer herding family outside Tromsø, Kittiwas approached for her skill in sewing and commissioned to create theSami-style gákti, fur and skin clothing and shoes, for Roald Amundsen’s GjøaExpedition through the Northwest Passage.

Margarthe KittiThis is Margarthe(Lango) Kitti. As a young girl from a reindeer herding family outside Tromsø, Kittiwas approached for her skill in sewing and commissioned to create theSami-style gákti, fur and skin clothing and shoes, for Roald Amundsen’s GjøaExpedition through the Northwest Passage. The idea ofemploying Sámi men, known for their abilities as skiers, on expeditions to thefrozen ends of the earth seems to have originated with Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld,who participated in three geological trips to Svalbard. On one such expeditionin 1872, he purchased forty reindeer and hired four Sámi men to take care ofthem, only one of whom is named: Nils Mathisen Sara. After Nordenskiöld’ssuccessful transit of the Northeast Passage, he set his sights on Greenland. In1883, Nordenskiöld recruited two hardy Sámi men, Pava Lars Tuorda and AndersRassa, to sail with him and his team of scientists to the west coast ofGreenland and from there see if they could cross overland to the east coast.

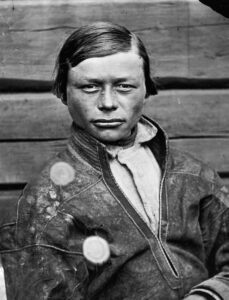

Pava Lars Tuorda

Pava Lars TuordaPava Lars Tuorda wasborn in the Tuorpan siida, in the mountains west of Jokkmokk, Sweden in1847. He early showed himself to be a skier of great endurance and an excellenthunter of wolves and bears, with spear and rifle. In the 1860s he was hired asa guide for Swedish geographers who were in the process of mapping areas ofNorrbotten province. In addition to bearing large loads, Tuorda was adept atfinding routes through challenging terrains. Asked for other recommendations,Tuorda suggested his neighbor Anders Rassa. The two men sailed off in the Sophiefrom Göteborg with the rest of Nordenskiöld’s team in June 1883 for the westcoast of Greenland.

One ofNordenskiöld’s theories was that he might discover a warmer center to theworld’s largest island, where trees and other vegetation could conceivablythrive in a drier climate away from the coast. But the team, burdened with amassive amount of equipment, found it difficult to navigate their sledgesacross Greenland’s glacial fissures and the deep snow that hid wet pocketsunderneath. Tuorda took the lead, but eventually Nordenskiöld decided thesledges could no longer go on. Instead, he sent Tuorda and Rassa ahead. Withtwo compasses, a barometer, and a pocket watch, they were to ski as far as theycould inland. Tuorda also took his bear spear. In the next fifty-two hours thetwo Sámi skied east 143 miles and then turned around and skied back, restingonly two hours during that time, when they were enveloped in a snowstorm andhad to dig themselves into the snow until it passed. They found no grass ortrees, only endless vistas of ice and snow.

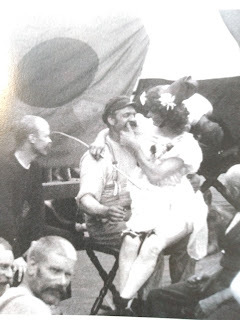

Per Saivo (l.) and Ole Must,1898

Per Saivo (l.) and Ole Must,1898 Anotherpair of Sámi men who participated in Arctic exploration were Ole Must and PerSaivo from Kirkenes. Thesetwo young men had their photographs taken by Elissif Wessel before they leftfor the South Pole on the British Antarctic Expedition 1898-1900, headed by theNorwegian-British leader, Carsten Borchgrevink, and with the aim of collectingscientific data, including fixing the location of magnetic south pole, and thenadvancing as far as possible towards the pole itself. The expedition’s crew,almost all Norwegian, successfully spent the winter of 1899 in twoprefabricated houses on the Antarctic mainland and managed to get by sledge to78° 50′ S., setting the “farthest south” record of the time.

August 4, 2025

Queering Polar History in Tromsø

Queering Polar History, an exhibit at the Polar Museum in Tromsø, just ended this past June. Sadly, I only became aware of it recently, though I was in Tromsø twice during the three years it was on. My focus in Tromsø both times was library research on Sámi folktales, and I didn’t have much time to revisit museums I’d already been to over the years. I also recalled the Polar Museum, in a remodeled wooden warehouse down on one of the city wharves, as being a little too taxidermic for my taste.

But on October 7, 2022, a temporary exhibit opened in connection with Norway’s Queer Culture Year, a joint initiative from the Queer Archive at the University of Bergen, the Norwegian National Museum, and the Norwegian National Library. This was to mark the 50th anniversary of the decriminalization of male homosexuality in Norway. The repeal of section 213 of the Norwegian Penal Code marked the beginning of a greater openness about gay life, literature, and activism, which would transform Norwegian society in the coming years.

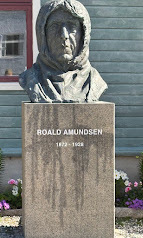

The Polar Museum is in many ways an unlikely venue for a thematic exploration of gender and sexuality in Northern Norway and the polar regions, particularly the Arctic. Due to the preponderance of male explorers, polar exploration has usually been associated with a certain kind of obsessive, fur-clad hypermasculinity, exemplified by Norwegians Fridtjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen and the many other men who participated in various late nineteenth and twentieth century races to the poles.

Curators and cultural studies researchers at the Polar Museum, Silje Gaupseth and Marit Anne Hauan, decided to take another look at material the museum might already have in its archives and at other newspaper clippings, fiction, artifacts, and urban legends suggested by external contributors with a knowledge of queer history. The result was an expanded look—in the exhibit itself and in a large format booklet with seven articles and an interview accompanying the exhibit—at the many dimensions of queer history.

One of the more intriguing articles focuses on a photograph from the Norwegian South Pole Expedition of 1910-12. It was snapped on the famous Fram, captained by Roald Amundsen, as the ship crossed the equator on December 14, 1910, en route to the South Pole. A celebration is in progress among the crew. A bit surprisingly, it includes what seems to be a woman in a short white costume, sitting on the lap of a crew member, with one arm around his neck and the other hand stroking his cheek. Second mate Hjalmar Fredrik Gertsen had, with the help of the ship’s sailmaker, had spent the day transforming himself into a ballerina, writing later that “I was extremely cute...and I was flirted with a lot.”

"The Equator Party," Fram 1910

"The Equator Party," Fram 1910In her fascinating article about this photograph, “A Few Square Metres of Leeway,” Gaupseth delves into the Anglo-American tradition of cross-dressing or “polar drag” aboard ship during performances, perhaps as a way of providing “a safe outlet for sexual tensions between the men on the expedition.” British officers had often been educated at schools where cross-dressing was encouraged in student theaters. After around 1920, such playful acting became more stigmatized as homosexual expression, but in 1910 it was alive and well on the Fram.

I was also captivated by Marit Anne Hauan’s article, “The Walrus—behavior among Arctic marine mammals that breaks the norms.” I mean, with a title like that, who wouldn’t wonder about what walruses are getting up to? Plenty, as it turns out. The Arctic walrus lives along the eastern coast of Greenland, and on the archipelagos of Svalbard and Franz Josef Land, and east along the Barents and Kara Sea. These large and magnificent animals, as well as their brethren, the Pacific walrus up in Alaska, were hunted almost to extinction.

Walruses are very social animals, as you can notice in the wild and in documentary videos and still photography. They always seem to be piled up together. Turns out, these are not mixed groups. Except for a short mating season in the winter, the male and female populations live separately. Although their mating and reproduction habits have been studied thoroughly by marine biologists, little research has taken place on what might be going on during the other ten months of the year. The sexual behavior of male walruses has received some attention in the past by Bruce Bagemihl, who is also the author of Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity , published in 1999. Apparently most male walruses engage in same-gender activity: making particular sounds associated with flirting, while masturbating their erect penis with their front flippers. Sometimes they rub up against the anal areas of other males.

This was all news to me, though I was not surprised to find that research on female walruses and their desires is still regrettably lacking.

The curators also asked the internationally feted queer Sámi photographer Gjert Rognli to create “interventions” at the Polar Museum. I am a great fan of his magical, often eerily lit nature photography, but the small photographs in the booklet of objects he contributed to the Queering Polar History exhibit didn’t give me a good sense of either his personal art style or what exactly they offered the viewer in the museum. On the other hand, his interview with Hauan is moving and perceptive about his own vision of queer art and his role in a “double minority position—Sámi and queer.”

Gjert Rognli

Gjert Rognli

July 24, 2025

Save the Repparfjord!

Protest site at Repparfjord, Norway, July 2025

Protest site at Repparfjord, Norway, July 2025This summer, on the site of a Canadian-financed copper mine on the mountain above the Repparfjord in Northern Norway, an encampment has gone up to protest the current construction and its ruinous consequences for Sámi reindeer grazing lands and the fjord near Hammerfest. You can read about the encampment here in a recent issue of the Barents Observer and see an Instagram video on the protest made by Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen, a young singer and activist affiliated with Norway’s environmental protection organization Natur og Ungdom (the youth movement of Friends of the Earth Norway). Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen asks everyone to write to the Canadian investment company Hartree to demand they stop funding this project, which is taking place without the consent of the Sámi parliament and many local Sámi in the area.

Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen

Ella Marie Hætta IsaksenFor more background on the project, read on:

The Repparfjord, or Riehppovuotna, is a National Salmon Fjord; the rivers that feed into the fjord from the mountains above are some of the world’s most pristine waterways, fished by the local Sámi for generations, and also beloved by fly fishermen from abroad. The fjord is a spawning ground for salmon, for cod, pollack, and other species. This marine environment was first threatened in the 1970s when the copper ore Nussir Mine in the mountains first came into operation with the promise of jobs for the nearby municipality of Kvalsund, a community of Sámi, Kven, and Norwegians located at the western end of the Repparfjord. Because of the falling price of copper, the open pit mine was only in existence from 1972-1978, but it was long enough for the company, Folldal Verk, to dispose of tailings (crushed rock, water, and trace amounts of metals or additives used in the processing) in the Repparfjord.

This was done without consulting the local population and the effects of the dumping were never monitored. But copper is now in great demand in the manufacture of electronics, and the amount of ore under the surface of two mountains above the Repparfjord, Ulveryggen (Gumpenjunni) and Steinfjellet (Nussir) is estimated at seventy-two million tons. Although Norway has a long history of copper mining farther south, in Røros and Løkken in the Trondelag area, the ore deposits around the Repparfjord are the largest known deposits in Norway. A renewed look at the Nussir brownfields began around 2005 with the establishment of an ASA (a public limited company), and some years of test drilling and raising money followed. The issue of what to do with the waste should mining be resumed was thoroughly discussed, but the plan was essentially the same as in the 1970s. The tailings would again spew into the Repparfjord, though this time the waste would flow through a pipeline from the plant to the fjord bottom. Dumping waste into waterways and the ocean has long been a human practice, but it’s a surprising fact that Norway is the only country in Europe and one of the last nation states to allow mining waste to be discarded in the ocean.

The Repparfjord

The RepparfjordThe mine was approved in 2019, with the goal of operating the world’s first fully electrified mine with zero CO2 emissions, but it has been bitterly fought ever since, with protests at the site driven by Sámi activists and other environmentalists. In 2020, the German company Aurubis, one of the world’s largest copper smelters, provisionally agreed to buy raw materials from Nussir ASA. A year later they terminated the memorandum of understanding after opposition, citing concerns about the effect on wildlife and the livelihoods of the Sámi in the area. The tailings were not the main issue; here it was the effect of the mine itself on local reindeer populations. Nussir ASA, in fighting for the mine, has insisted that the mitigation measures they propose will work, but most of those mitigation measures are on land. The Sámi Parliament, which in Norway is given the right of consultation but never the final say in any dispute over the environment, disagreed with Nussir ASA. The suggested mitigations were not sufficient.

There are conflicting ways of reading Norwegian laws and how they are to be interpreted with regard to Sámi rights. For instance, the Minerals Act of 2009 gives little agency to Sámi concerns, while the Natural Diversity Act, passed that same year, states that the purpose of the act “is to protect biological, geological and landscape diversity and ecological processes through conservation and sustainable use, and in such a way that the environment provides a basis for human activity, culture, health and well-being, now and in the future, including a basis for Sami culture.” There is currently a new Minerals Act, scheduled to go into effect in 2026, that speaks of “Extending the scope of the current special rules relating to Sámi interests to cover the entire traditional Sámi area.” But this revised Minerals Act is also focused on streamlining permits and encouraging production, in line with the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act of 2024. What some critics, Sámi and non-Sámi, have noticed is how little say the Sámi Parliament has over the marine environment. While the rights of land-based reindeer herders are often threatened, there has been progress at times in finding compromises and/or limiting damage. But the rights of the traditional Sea Sámi to clean waters and a healthy marine ecology seem to be more nebulous when it comes to the law.

Hammerfest protest against dumping in the fjord

Hammerfest protest against dumping in the fjordAlthough a number of people in the Kvalsund municipality are in favor of the mine because of the jobs involved and protests and continued pushback from the Sámi Parliament have slowed the process, the plans for the mine haven’t been given up. As of 2025, Blue Moon Metals of Canada is working with Nussir ASA to pursue mining operations. The Sámi Parliament President, Silje Karine Muotka, has been outspoken about the Nussir mine and about a “green shift” that depends on extractive processes that harm the environment and have an outsize effect on Indigenous populations in Norway. “It isn’t a question of economics, it’s a values question, a moral question about what we want to leave future generations. I do recognize that we need materials for new technologies – so we should look for better projects that don’t harm the environment and destroy our culture.”

Sámi Parliament President, Silje Karine Muotka

Sámi Parliament President, Silje Karine MuotkaJuly 15, 2025

University of Minnesota Press Celebrates 100 Years of Publishing

Warm congratulations to the University of Minnesota Press, which is celebrating its founding July 16, 1925. Publishers Weekly has an article about the press that highlights some of its achievements and goals publishing both trade books and scholarly titles. I've read many of their titles over the years, everything from cookbooks to mysteries and natural history memoirs, and so many of them have been memorable.

I'm pleased and grateful that Minnesota has published a number of my own books, both translations and original titles, like From Lapland to Sápmi and The Palace of the Snow Queen. The people who work there are dedicated to quality, professional, collaborative, and truly kind, and I know I'm not the only author who feels blessed to be part of their list. The covers and interiors are always beautiful and the production details perfect.

Congrats Minnesota, for managing to thrive for a century in a publishing world that's so often challenging for independent and university presses!

June 18, 2025

Women Write About Svalbard: Christiane Ritter, Cecilia Blomdahl, and Line Nagell Ylvisåker

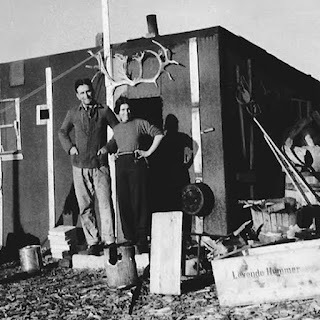

Christiane and Hermann Ritter in front of their house on Svalbard I’ve been dreaming these days about the polar regions, the Arcticin particular. In the midst of attemptingto digest a good deal of difficult news, which seems to fly at us from alldirections but mainly emanates from Washington D.C., I don’t want to forgetabout climate change. The melting glaciers of Greenland, Svalbard, and Antarcticaconcern us all. Long after this sinister administration is gone, we’ll beliving through the consequences of denying scientific research.

Christiane and Hermann Ritter in front of their house on Svalbard I’ve been dreaming these days about the polar regions, the Arcticin particular. In the midst of attemptingto digest a good deal of difficult news, which seems to fly at us from alldirections but mainly emanates from Washington D.C., I don’t want to forgetabout climate change. The melting glaciers of Greenland, Svalbard, and Antarcticaconcern us all. Long after this sinister administration is gone, we’ll beliving through the consequences of denying scientific research. I'm thinking about the environment as I work on my currentproject, a memoir about my travels up in Arctic Norway last summer. But I've also been paying attention to those who have traveled and lived up in the high North. I’ve been researching the Norwegian explorers, FridtjofNansen and Roald Amundsen; the Sámi members of expeditions to Greenlandand Antarctica; Tromsø’s role as an Arctic research center. And then, of course, there’s Svalbard. I visited the archipelago briefly once decades ago when I worked on the Norwegian coastal steamerone summer, and the memory of the polar ice north of Ny Ålesund is still powerful.

Which brings me to two books I’ve recently read, and another I've only read about, written by womenwho lived or are living on Svalbard. Books that couldn’t bemore different in scope, format, and tone, but that taken together say somethingabout the ways in which woman have experienced the North and also projectedthemselves into it.

A Woman in the Polar Night, by Christiane Ritter, isa translation from the German that originally came out in 1938 (in 1954 in England).This short memoir has stayed in print in her native Austria ever since but was aforgotten classic when Pushkin Press reissued it in 2024. It’s the account of ayear that Ritter, then in her early thirties, spent with her husband, Hermann,a naval officer who went to Svalbard on a scientific expedition and stayed tobecome a trapper and hunter. He telegraphed her to come and join him and in1934 she did, leaving behind her teenage daughter and the comforts of life inVienna.

A Woman in the Polar Night, by Christiane Ritter, isa translation from the German that originally came out in 1938 (in 1954 in England).This short memoir has stayed in print in her native Austria ever since but was aforgotten classic when Pushkin Press reissued it in 2024. It’s the account of ayear that Ritter, then in her early thirties, spent with her husband, Hermann,a naval officer who went to Svalbard on a scientific expedition and stayed tobecome a trapper and hunter. He telegraphed her to come and join him and in1934 she did, leaving behind her teenage daughter and the comforts of life inVienna. Ritter tells us almost nothing about that old life. From themoment she arrives, she is fully present in the overwhelming world of Svalbard,which at first shocks her with its emptiness and desolation, even at summer’stail end: “The boundlessly broad foreland, a sea of stone, stones stretching upto the crumbling mountains and down to the crumbling shore, an arid picture ofdeath and decay.”

But as the months progress, her experience changes. Thestove is primitive and sooty; the menu relies too heavily on oily seal meat,the polar night descends unmercifully. While the Aurora and the stars whirlaround dark sky, the shack can feel alternately cozy and claustrophobic. Ritter feels at times small and afraid, especially when left for days alone in thecabin she and Hermann share with a younger Norwegian, Karl, when the men areout hunting. But if her descriptions of the effort of daily existence areprecise and sometimes humorous, her writing about the mountains, fjords andespecially the ice, the snow, and the changing light as autumn becomes winterand winter becomes spring begins at times to rise to an exultation that wecommonly associate with saints in the grip of an ecstatic vision of God and theuniverse. At one point Ritter displays hints of an Arctic madness—she becomes,Karl’s brief formulation, rar, the Norwegian word for “strange.”

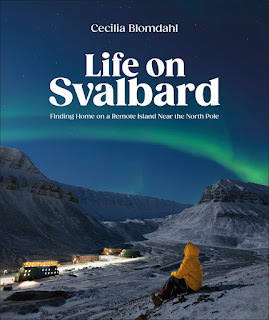

Swedish photographer Cecilia Blomdahl’s 2024 coffee table book, Life on Svalbard, couldn’t be more different in scope, format, and mood. AWoman in the Polar Night is austere and poetic; Christiane Ritter relies onher pen to create indelible imagery. There are only a few sketches and blackand white photographs. She’s modest to a fault; we could wish we knew moreabout her. What kind of art does she make and how does she support herself? Whyis her husband in Svalbard and is he ever coming home? What does she thinkabout the political situation in Central Europe and the rise of National Socialism?

Blomdahl inhabits another world entirely, that of a contentcreator across multiple social media channels. She’s on Instagram, she’s onTik-Tok, she’s on Facebook, and she’s on YouTube, where she’s made 500 videosof her life near the main town of Longyearbyen. One of them from a few years ago,explaining “THIS is why I live on a remote Arctic island with 3000 people and polar bears,” has garnered over 4 million views. Blomdahl cameto Svalbard in 2016 to work in the hospitality field. She immediately took to the cold and extremes of light and dark overthe course of the year. With her Norwegian boyfriend, initially a cook at thesame hotel, she moved a short way outside Longyearbyen to a cabin with a viewof seven glaciers. From there she discovered photography as a way ofcommunicating with hundreds of thousands of people across the globe, who alsodream of cold, remote places, but perhaps don’t actually want to go there. Theywould rather watch Blomdahl in snowsuits on her snowmobile, or in her longunderwear reading a book, or in her swimsuit braving an icy dip. She’s oftenphotographed from behind, staring at the landscape, her brown hairflowing, or sitting on the porch or inside the cabin, with a steaming cup ofcoffee, demonstrating hygge in the midst of wilderness. Svalbard isthere, in full view, but as she says in one video, “Svalbard is a feeling, it’sa lifestyle, not just a place.” Her viewers write comments praising herpositivity. They seem to love the combination of gentle reality show superimposedon a harsh but stunning northern landscape.

Life on Svalbard has many gorgeous photos but the Englishtext is oddly flat. I believe she writes in English much as she speaks, withonly a slight Swedish accent, using pedestrian phrases that come from thetourist industry. Blomdahl wants to convey the ineffable, but the words that come out onlygrasp vaguely in that direction. There is much that is “breathtaking” or that“takes your breath away.” And although there are also possibledangers—avalanches, walruses, polar bears—there are many domestic pleasures. Cecilieand Christoffer have GPS to find their way to even more remote cabins on theisland of Spitzbergen. They get shipments from Ikea to remodel their kitchen. Theyvisit with friends and drink coffee. They play with their dog Grim. Withsnowmobiles, cars, boats, wi-fi, and their vast audience, they are living aEuropean lifestyle in a place that once was only for the toughest-minded survivalist.

Life on Svalbard has many gorgeous photos but the Englishtext is oddly flat. I believe she writes in English much as she speaks, withonly a slight Swedish accent, using pedestrian phrases that come from thetourist industry. Blomdahl wants to convey the ineffable, but the words that come out onlygrasp vaguely in that direction. There is much that is “breathtaking” or that“takes your breath away.” And although there are also possibledangers—avalanches, walruses, polar bears—there are many domestic pleasures. Cecilieand Christoffer have GPS to find their way to even more remote cabins on theisland of Spitzbergen. They get shipments from Ikea to remodel their kitchen. Theyvisit with friends and drink coffee. They play with their dog Grim. Withsnowmobiles, cars, boats, wi-fi, and their vast audience, they are living aEuropean lifestyle in a place that once was only for the toughest-minded survivalist.

Although Svalbard is one of the places most at risk in thesetimes of climate change, and although much of the research that goes on inLongyearbyen and farther north at the research station in Ny Ålesund has to do with rapidlymelting glaciers and warming seas, there’s nothing about that inconvenienttruth in Life on Svalbard. We don’t learn much about the archipelago’shistory as a whaling station or its mining operations, or about its connection withNorway and its political structure. It’s an innocuous book, with gloriousvisuals, but unreal somehow. Blomdahl mentions the presence of researchers butdoesn’t explain what they are studying. The couple’s friends may also be fromthe hospitality field—after all, you have to have a job or an income to beallowed to stay in Svalbard—but mostly they are engaged in leisure activities.Don’t get me wrong, Cecilia Blomdahl’s photographs are striking, but they areoddly detached from the lives of most people on the archipelago.

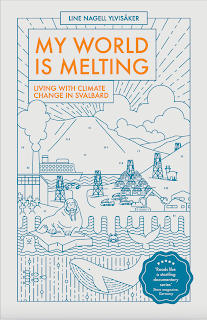

C hristiane Ritter’s book was written before an understandingof the effects of climate change on glaciers, but for Cecilia Blomdahl there’sreally no excuse. After all, in 2015 a devastating avalanche hitLongyearbyen during a strong winter storm. Houses were damaged, people wereevacuated temporarily, and one man was killed. The story of the avalanche andits aftermath are told in a 2020 book My World is Melting – Living withClimate Change in Svalbard, by the Norwegian journalist and longtimeSvalbard resident, Line NagellYlvisåker, who is also the editor of Longyearbyen’s newspaper. Although thebook was translated to English in 2022, that edition is only available onSvalbard itself. In lieu of my own take on the book, I offer for now a review I foundonline by a Dutch meteorologist, Daan van den Broek, who isbased in Finland and travels often to Svalbard.

hristiane Ritter’s book was written before an understandingof the effects of climate change on glaciers, but for Cecilia Blomdahl there’sreally no excuse. After all, in 2015 a devastating avalanche hitLongyearbyen during a strong winter storm. Houses were damaged, people wereevacuated temporarily, and one man was killed. The story of the avalanche andits aftermath are told in a 2020 book My World is Melting – Living withClimate Change in Svalbard, by the Norwegian journalist and longtimeSvalbard resident, Line NagellYlvisåker, who is also the editor of Longyearbyen’s newspaper. Although thebook was translated to English in 2022, that edition is only available onSvalbard itself. In lieu of my own take on the book, I offer for now a review I foundonline by a Dutch meteorologist, Daan van den Broek, who isbased in Finland and travels often to Svalbard.

May 7, 2025

The Agency of Sea Ice: Sohvi Kangasluoma Overwinters in a Sailboat in Greenland

In 1897 Fridtjof Nansen published Farthest North, hisnarrative about the three years he spent in the Arctic, part of it on thefamous ship, the Fram, and part of it attempting to sledge to the NorthPole with one companion from the ship and being turned back by the ice to facea harrowing fifteen months before being rescued on Franz Josef Land. I readthis book quite recently and still am thinking about the amazing factthat he, all his companions on the ship, and the Fram itself survivedthree years of polar weather and challenges. They didn’t reach the pole butthey did get within a few degrees. Some of the most entrancing sections of thebook are the descriptions of the cozy interior of the ship; locked into the iceand drifting west in the direction of Svalbard, the expedition team read books,ate nice meals with desserts, and played cards, while the wind howled and thesnow fell outside.

Nansen studied to become a marine biologist before he becamea polar hero and later a statesman with a side line in oceanography. In theintroduction to Farthest North he lays out a short history of attemptsto reach the North Pole by ship, and the many disasters. He explains his owntheory of ocean currents that run west from Siberia to Greenland and how they couldhelp, not hinder a ship in an expedition to the Pole.

In memorable and prescient words, he writes, “I believethat if we pay attention to the actually existent forces of nature, and seek towork with and not against them, we shall thus find the safest andeasiest method of reaching the Pole.”

Sohvi Kangasluoma with her dog on the ice

Sohvi Kangasluoma with her dog on the iceThe other day I had cause to remember those words, when I readan article in the HighNorth News (April 30, 2025) about Dr. Sohvi Kangasluoma, a youngwoman scientist from Finland who’s taken some of Nansen’s ideas further. Kangasluoma, a post-doc at the Arctic Centre at the University of Lapland, livesand works with her partner Juho Karhu in their sailboat. Lastsummer the couple transited the Northwest Passage from Alaska to Greenland to studythe movement of ice. In the winter of 2024-2025 they embedded the boat in packice off the east coast of Greenland.

Kangasluoma’s dissertation is titled Understanding Arcticoil and gas: Entanglements of gender, emotions and environment (and can bedownloaded here).In the High North article she discusses the ways that the Arctic iscurrently viewed as a geopolitical prize to be fought over, Kangasluoma has pointedout that sea ice “is approached as something that just is and melts. Butit is anything but a passive and dead thing; it is very much alive, and it hasagency of its own."

Like other researchers influenced by feminist and ecologicalviews of nature, Sohvi Kangasluoma, looked beyond the sea as only a place toextract wealth, whether in the form of fish, minerals, or oil and natural gas,an enormous site of geopolitical greed and political conflict. She researchedthe Arctic seas with an eye to the non-human. "We tend to have this veryanthropocentric way of thinking. Humans need a shift in knowledge. Humans arenot alone here; there are so many other actors as well. This is, of course,already present in many Indigenous ontologies and ways of life, which we needto start listening to."

The article has a link to a video called “Turning Our Boatinto an Igloo.” The YouTubechannel, Alluring Arctic Sailing, has other videos equally fascinating. It's maintained by Juho Karhu,who has a scientific background as well and contributes to voluntary researchprojects. His voice and manner are incredibly calm, no matter whatseems to be happening on the ice or how hard the wind is blowing.

April 3, 2025

Sápmi Lands Threatened by EU’s Approval of Raw Materials Strategic Projects

News that the mining projects Talga Graphite in Nunasvaara,LKAB ReeMap in Malmberget, and LKAB Per Geijer in Kiruna were part of a mass approval on March 24, 2025by the European Commission was a shock to the Sámi Council, which has issued astrong statement.Other sites are located in the Sámi part of Finland. The mining projects ontraditional Sámi territory, some of 47 “strategic projects” around Europe, arethe result the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act on May 23, 2024, aimed at reducingsupply chain vulnerabilities. Many of the areas to be mined can also producethe raw materials required in a conversion to so-called green energy.

News that the mining projects Talga Graphite in Nunasvaara,LKAB ReeMap in Malmberget, and LKAB Per Geijer in Kiruna were part of a mass approval on March 24, 2025by the European Commission was a shock to the Sámi Council, which has issued astrong statement.Other sites are located in the Sámi part of Finland. The mining projects ontraditional Sámi territory, some of 47 “strategic projects” around Europe, arethe result the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act on May 23, 2024, aimed at reducingsupply chain vulnerabilities. Many of the areas to be mined can also producethe raw materials required in a conversion to so-called green energy. The Sámi Council, along with the Sámi parliaments in theNordic countries have long made it clear that they lack the legal staff andfunding to tackle the impacts of each proposed project on the environment andSámi culture, a culture closely interwoven with the landscape. Internationalcorporations had already been expanding in Sápmi. The Australian company, Talga, for instance, whichplans to mine graphite in the winter reindeer grazing lands around Vittangi,near Kiruna, has long fought court battles with the Talma Sámi siida. Now,thanks to the fast-tracked status of the project given by the EU, the projectcan move ahead without the Sámi being likely to mount an effective defense.

“The EU is promoting the exploitation of minerals thatcontribute to human rights abuses within the EU,” Per-Olof Nutti, president ofthe Saami Council said. “This is a direct violation of our rights as the onlyrecognized Indigenous People within the EU.”

March 31, 2025

Siri Broch Johansen Awarded Ibsen Prize

Siri Broch JohansenThe Ibsen Prize is Norway's only drama award and considered one of the most prestigious international drama prizes. Last week, on March 20 (Ibsen's birthday), in a first for a Sámi author, Siri Broch Johansen was awarded the Ibsen Prize for her play, Per Hansen: A Faithful Man/oskkáldas almmái which premiered in October, 2024 at Norway's traveling theater, Riksteatret.

Siri Broch JohansenThe Ibsen Prize is Norway's only drama award and considered one of the most prestigious international drama prizes. Last week, on March 20 (Ibsen's birthday), in a first for a Sámi author, Siri Broch Johansen was awarded the Ibsen Prize for her play, Per Hansen: A Faithful Man/oskkáldas almmái which premiered in October, 2024 at Norway's traveling theater, Riksteatret.Per Hansen: A Faithful Man is described on the theater's website as “a juicy, humorous, steamyerotic, and honest piece. It's about adult love, complex life choices, andenduring this life.” A rave review on NRK celebrates how the two characters, both Sámi, explore a relationship outside marriage, with all the heartbreak and loneliness that can involve.

Much of the action takes place on a sofa as the actors talk about sex, desire, and what's possible in explicit terms. From the reviews, it seems that Norway has never seen Sámi people through this lens before--as ordinary, not particularly exotic human beings--yet still Sámi for all that.

Siri Broch Johansen is, in addition to an author of several books, a language teacher and singer, living in the Tana municipality in East Finnmark/Sápmi. I know her work from her biography of the Sámi activist Elsa Laula Renberg, published in 2015.

[image error]