Jon Ronson's Blog, page 5

January 30, 2015

My conversation with Adam Curtis (reprinted from Vice magazine)

This is getting linked to all over the place, which I find thrilling despite Adam and I claiming to scorn that sort of thing in the piece.

I’ve known Adam Curtis for nearly 20 years. We’re friends. We see movies together, and once even went to Romania on a mini-break to attend an auction of Nicolae Ceausescu’s belongings. But it would be wrong to characterise our friendship as frivolous. Most of the time when we’re together I’m just intensely cross-questioning him about some new book idea I have.

Sometimes Adam will say something that seems baffling and wrong at the time, but makes perfect sense a few years later. I could give you lots of examples, but here’s one: I’m about to publish a book – So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed – about how social media is evolving into a cold and conservative place, a giant echo chamber where what we believe is constantly reinforced by people who believe the same thing, and when people step out of line in the smallest ways we destroy them. Adam was warning me about Twitter’s propensity to turn this way six years ago, when it was still a Garden of Eden. Sometimes talking to Adam feels like finding the results of some horse race of the future, where the long-shot horse wins.

I suppose it’s no surprise that Adam would notice this stuff about social media so early on. It’s what his films are almost always about – power and social control. However, people don’t only enjoy them for the subject matter, but for how they look, too – his wonderful, strange use of archive.

His new film, Bitter Lake, is his most experimental yet. And I think it’s his best. It’s still journalism: it’s about our relationship with Afghanistan, and how we don’t know what to do, and so we just repeat the mistakes of the past. But he’s allowed his use of archive to blossom crazily. Fifty percent of the film has no commentary. Instead, he’s created this dreamlike, fantastical collage from historical footage and raw, unedited news footage. Sometimes it’s just a shot of a man walking down a road in some Afghan town, and you don’t know why he’s chosen it, and then something happens and you think, ‘Ah!’ (Or, more often, ‘Oh God.’) It might be something small and odd. Or it might be something huge and terrible.

Nightmarish things happen in Bitter Lake. There are shots of people dying. It’s a film that could never be on TV. It’s too disturbing. And it’s too long as well – nearly two and a half hours. And so he’s putting it straight onto BBC iPlayer. I think, with this film, he’s invented a whole new way of telling a nonfiction story.

VICE asked the two of us to have an email conversation about his work. We started just before Christmas, and carried on until after the New Year.

Jon Ronson: I’ve known you nearly 20 years, but I have no idea how you spend your days. I have a mental picture of you in your own special archive room in some BBC building, day after day, hacking through arcane archive like Doctor Livingstone, trying to find some marriage of your ideas and someone else’s pictures. Is that what it’s like? Do you have a special room? If so, what does it look like? Does it have windows? Do you get annoyed if people disturb you?

Adam Curtis: I don’t have a special room. Most of the archive I watch is stored down in a giant series of anonymous sheds in West London. A lot of it I can borrow and watch in giant BBC open plan offices. It is a bit odd, because as well as ordering up films directly related to what I’m researching, I also order all kinds of other stuff that I think might have images that I could use – guided by my instinct and imagination. So people walking past see me watching this endless strange collage of material. From a film about Mrs Thatcher giving fashion tips on how to dress well in 1987, to a programme about people who had visions during epileptic fits, to a documentary about Hells Angels taking a weekend mini-break on a canal barge in the British countryside in 1973. I do get people asking why I’m watching this odd mix. It can be difficult to explain because, to be honest, I don’t really know myself sometimes. I’ve just let my mind drift.

What I look for in the archive are shots that I can use to create a mood that gives power and force to the story I’m telling. So much factual stuff on television and film is so insistently literal, like doomy Arvo Pärt music over pictures of bad things that have happened. And they think that’s emotion. But those are cliches that actually make you feel strangely unemotional.

What I don’t tell anyone about are the hidden levels in the BBC archive – the stuff that’s there that isn’t on the normal catalogues. The secret levels of images from, what, 70 years of continuous filming?

What do you mean by secret levels? You mean the stuff when people don’t quite realise they’re being filmed? There’s a moment in Bitter Lake when a bomb goes off in the desert and the cameraman misses it. And he goes, “Fuck.” And so he pans left and there’s the explosion: a huge plume of smoke and sand going up to the sky. And he’s so disappointed and annoyed to have missed it. Is this what you mean about the secret levels? Or do you mean something completely different?

What I began to discover was all sorts of hidden material in the BBC archives. And it wasn’t just forgotten films or misclassified stuff – although there’s quite a lot of that. I also discovered different kinds of recorded realities.

So, for example, I stumbled on what are called the Comp Tapes. These are thousands of videotapes that, from the 1970s through to the 1990s, were used every day to record satellite feeds of material coming through for news. Often it’s just a live feed, like one I found of a camera in a helicopter hovering over the LA hills in 1981 watching police search for – and find – a body of a woman who’d been murdered by the Hillside strangler. But because the feeds are over satellite they often break up into the most beautiful abstract coloured shapes, and then the image clicks back in.

Then I found a man in the archives who spends his time recording the bits in between the programmes when they are broadcast. He writes down in detail all the announcements and the trailers, plus all the bits where things go wrong. So far his log of this stuff has got to 7,500 pages. He’s convinced that we don’t really understand television. He says the idea that you can break television up into discrete programmes is wrong. He believes television is really one long construction of a giant story out of fragments of recorded reality from all over the world that is constantly added to every day, and has been going on for 70 years.

But what really opened things up for me was the realisation that there was an even further forgotten source of images. Not in London, but hidden all over the world. A BBC news cameraman called Phil Goodwin came to me and told me that the BBC offices in major cities have kept all their recorded footage in cupboards and store rooms. There are hundreds of tapes of what are called rushes – the original, unedited material from which news reports are created. And they were just lying there.

To prove this, Phil went to Kabul and spent weeks digitising the rushes. He brought them back to London and no one wanted them. But I was very interested, so he gave them to me.

And I started to watch them. And it was amazing. Hundreds of thousands of hours of moments recorded. Ten or 20 seconds would have been taken out of some of the tapes for a news report. Other tapes would never have been touched. Forgotten. They would never ever have been seen by anyone. Like trees in a forest, falling – you know that thing. But together, what they recorded was an extraordinary world – something so completely different from the simple stories we are told both by TV journalists and politicians. That’s where I started.

A few years ago I presented a documentary about a foiled school shooting in a Christmas theme town in Alaska. The kids there have to pretend to be elves for the tourists, and a bunch of them were arrested in the final stages of planning a school shooting. So I went there to find out whether all that Christmas had turned the kids crazy – like When Elves Go Bad.

Usually I direct my own documentaries, but this time Channel 4 paired me with a director. The reason why I bring it up now is that it didn’t work out. When I went into the edit to watch the rough cut I saw that the director had kept in all the backstage stuff – the little banal chats I had with people before doing the interview. I felt really embarrassed to see my ungainly little offstage moments. And the edit became really tense. I was fighting to take them out and she was fighting to leave them in.

Bitter Lake has lots of moments where you’ve left in telling offstage snippets of conversations between the camera people and the directors. Of course, you aren’t doing anything mean – you aren’t naming and shaming your fellow BBC people or anything like that. None of them are identifiable in any way. And your motives couldn’t be more serious. It’s a totally different situation to my bad Alaska experience. But I was thinking: because you’re a BBC person too, did you ever feel like you were doing something your colleagues might not like?

Your Alaska thing is very funny – and I’m glad you’re not in my film. But the people in the rushes I have used are doing something very different. They are really brave journalists and technical people going into an incredibly complex situation and trying to make sense of it. And, in a way, they are the heroes of my film.

I’ve taken care not to criticise or shame any of them. But, to be honest, it would be difficult, because what’s sitting there in those thousands of hours of footage is an amazing achievement. It is a group of women and men going into the most difficult, frightening and strange situation, and recording it in incredibly intelligent and imaginative ways. Some of the camera-work is so brilliant. It has that modern eye that you find in some movies. The camera does what you yourself would do instinctively in the situation – and as it hunts and looks you get the most unexpected compositions.

The problem is how that material is then used, when it’s processed through broadcast central. It is taken and fitted into increasingly rigid formats in TV that tend to remove the very thing that has been captured so well in the original rushes: the emotional truth of the situation. What it felt like to be there. And what you would think if you yourself were there.

It’s part of a much bigger problem. I’m not just talking about news, but about all factual reporting on television. The way they tell stories about the world feels increasingly thin – and more and more detached from the way all of us think and feel. Journalism used to open up reality to tell us new stuff. But now it is helping to keep us all inside the bubble by playing back stuff we already know in slightly altered forms.

So I’ve taken all that unedited material from Afghanistan and tried to use it in a new way. My aim is both to show the complex reality that we didn’t see in Afghanistan, but also to try and do it in a way that’s more emotional and involving. Some of it is quite radical, but I think you have to try and do that if you want to puncture the bubble.

Our age is a highly emotional one. It’s a time where what people feel as individuals is really important. I’m not saying that journalism should just become a wash of feeling and simply pander to that emotionalism. Journalism’s job should always be to explain things to you. But in our age it should do that with real emotional power.

But it doesn’t. It has become rigid and full of cliches, and in response people turn away and immerse themselves in the stories of themselves and their friends’ lives. Which is exciting – and a new kind of world – but it leaves large parts of the public world completely unexamined, which means that people in power can do more and more what they like.

I don’t agree with your last point. Yes, there are a lot of self-absorbed tweets out there. But social media is also very political. Look at the Black Lives Matter protests – organised and promoted on social media. Actually, I think the problem is that social media has become too political. This is partly what So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed is about. Some of our social justice campaigns have worked. But one result is that we’ve become so keen to right political wrongs we do it even when there aren’t any wrongs to right. So somebody gets destroyed for telling a joke on Twitter that comes out badly. People are getting destroyed for bad wording. And their fate is so horrendous it’s frightening all of us into behaving in a more conformist way.

I’m afraid I disagree with you that social media is a new kind of politics. It’s a powerful new tool for helping to organise people – that is true. But what it really doesn’t offer is a new kind of political way of changing the world. And, in fact, the belief that it does, and the failure of that, can lead to the most conservative situation.

Let’s analyse what happened to the Arab Spring. Because that is often held up by the tech-utopians as the evidence for social media’s revolutionary potential. In the Arab Spring all the liberal middle classes in places like Egypt came out to protest, summoned by social media. But then, once the revolution – or revolts – happened they had absolutely no idea of what to do. In the face of forces like the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists, who had a powerful idea, the Twitter and Facebook networks were completely incapable of coming up with something new and powerful that could challenge the Brotherhood or the Salafists.

All they did was keep tweeting each other about how they all agreed that what was happening was terrible. And, in the process, they became trapped in an echo chamber that completely stopped them looking at the world from other people’s points of view, and thus finding ways to effectively challenge the opposing point of view imaginatively. They got trapped in a system of feedback reinforcement.

Then the generals had a coup and all those liberals sighed a big sigh of relief and they tweeted each other that this was really a good thing.

You tell me anywhere in the Arab Spring where the ideas of those who used social media have risen up to become dominant. From Tunisia to Egypt and Yemen to Bahrain, those very groups who based their faith in social media have completely failed to have any substantial influence on power. Those doing well are ironically the traditionalists who have a powerful cultural conservative vision. Except, of course, Syria, where, as you know, the liberal middle classes are doing really well.

But I do really agree with you about Twitter domestically. Twitter – and other social media – passes lots of information around. But it tends to be the kind of information that people know that others in that particular network will like and approve of. So what you get is a kind of mutual grooming. One person sends on information that they know others will respond to in accepted ways. And then, in return, those others will like the person who gave them that piece of information.

So information becomes a currency through which you buy friends and become accepted into the system. That makes it very difficult for bits of information that challenge the accepted views to get into the system. They tend to get squeezed out.

I think the thing that proves my point dramatically are the waves of shaming that wash through social media – the thing you have spotted and describe so well in your book. It’s what happens when someone says something, or does something, that disturbs the agreed protocols of the system. The other parts react furiously and try to eject that destabilising fragment and regain stability.

I don’t think these waves are “political” in the liberal way the shamers proudly think. They are political in a completely different way, because they work to create a static, conservative world where nothing really changes.

What I find so fascinating in your book is the intensity of the reaction – the fury of the shaming. And I think this is possibly due to an underlying frustration among people in the network not being able to escape the static confines of their web.

I have this perverse theory that, in about ten years, sections of the internet will have become like the American inner cities of the 1980s. Like a John Carpenter film – where, among the ruins, there are fierce warrior gangs, all with their own complex codes and rules – and all shouting at each other. And everyone else will have fled to the suburbs of the internet, where you can move on and change the world. I think those suburbs are going to be the exciting, dynamic future of the internet. But to build them I think it will be necessary to leave the warrior trolls behind. And to move beyond the tech-utopianism that simply says that passing information around a network is a new form of democracy. That is naive, because it ignores the realities of power.

Why do you believe journalism changed? You say it used to be about “opening up reality to tell us new stuff. But now it is helping to keep us all inside the bubble by playing back stuff we already know in slightly altered forms.” Why the change?

The thing that fascinates me about modern journalism is that people started turning away from it before the rise of the internet. Or, at least, in my experience that’s what happened. Which has made me a bit distrustful of all that “blame the internet” rhetoric about the death of newspapers.

I think there was a much deeper reason. It’s that journalists began to find the changes that were happening in the world very difficult to describe in ways that grabbed their readers’ imagination.

It’s intimately related to what has happened to politics, because journalism and politics are so inextricably linked. I describe in the film how, as politicians were faced with growing chaos and complexity from the 1980s onwards, they handed power to other institutions. Above all to finance, but also to computer and managerial systems.

But the politicians still wanted to change the world – and retain their status. So in response they reinvented other parts of the world they thought they could control into incredibly simplistic fables of good versus evil. I think Tony Blair is the clearest example of this – a man who handed power in domestic policy making over to focus groups, and then decided to go and invade Iraq.

And I think this process led journalism to face the same problem. They discovered that the new motors of power – finance and the technical systems that run it, algorithms that try and read the past to manage the future, managerial systems based on risk and “measured outcomes” – are not just obscure and boring. They are almost impossible to turn into gripping narratives. I mean, I find them a nightmare to make films about, because there is nothing visual, just people in modern offices doing keystrokes on computers.

Right. I write about this in The Psychopath Test. In 2006 I tried to write a book about the credit industry, but I abandoned the idea three months later for that same reason. It made me realise that if you have the ambition to become a Bond-style arch villain, the first thing you should do is learn to be boring. Don’t act like Blofeld – monocled and ostentatious. We journalists love writing about eccentrics. We hate writing about boring people. It makes us look bad: the duller the interviewee, the duller the prose. If you want to get away with wielding true, malevolent power, be boring.

So large parts of journalism did exactly what Tony Blair did. On the one hand they went down the focus group road, which is what is now called consumer-journalism. On the other, they simplified the world into a black-and-white picture of terrible dangers that threaten their readers. Frightening warlords and people-traffickers, paedophiles prowling the internet, terrorist masterminds in caves, and killer foods.

And they largely ignored the really important shifts in power that were happening – so they went unexamined. And even when something like the crash happened in 2008, it was portrayed as a bunch of evil bankers. And much larger questions are ignored, like, “What has happened to the very idea of money?” Has it mutated into a strange virus that is taking over all institutions and private parts of people’s lives, so everything becomes monetised?

And now I think journalism has retreated into the past to find its baddies. And to be honest, I’m extremely guilty of this myself – constantly going back into the past and reworking it in new ways. It’s because none of us seem to be able to imagine other futures, alternatives to the complex muddle we have at the moment.

So, at present, we get a continuous, ferocious vaudeville of aged DJs and light entertainers exposed for their past crimes.

I’m not saying that is wrong; it is right for any kind of sexual abuse to be punished. But at the same time, all the other, modern, crimes that are being exposed – in finance, in the intelligence agencies, by which I mean torture, and in the new companies to which so much of the state is being outsourced – go largely unpunished. Plus, we the audience seems not to care about those modern crimes – and instead turn our heads to see what entertainer might be hauled up for our delight this week.

And we are trapped by that endless vaudeville.

When that happens you know that something rather odd has occurred to journalism – and, interestingly, to the law as well.

Adam Curtis’ new film Bitter Lake will be available on BBC iPlayer from 9PM on Sunday the 25th of January.

Jon Ronson’s new book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (Picador), is released on the 12th of March.

December 19, 2014

The Ballad of Ruby Ridge special screening - Jan 15, Brooklyn

So last night we showed my old film - The Ballad of Ruby Ridge - at the Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn (which has quite the collection of casts of what happens to your face when you get syphilis, btw).

We didn’t get a huge audience because it was the week before Christmas and I think a lot of people chose Christmas parties over a horrific documentary about a terrible family tragedy.

But I felt so proud to watch it again - it’s the best documentary I’ve ever been involved with. And so we’ve decided to show it again, on January 15th.

It’s one of those films that the less you know the better. But I’ll tell you how the film came to be. My friend, the documentary producer Fenton Bailey, sent me a box of VHSs back in the mid-1990s. He was clearing out his offices and wondered if I wanted to look through them. I watched. Most were crappy anti-NWO pre-Internet cable access talk shows. But one was different.

It was amateur footage shot on a mountain in Idaho. Something terrible was happening up the mountain, but it was hard to work out exactly what. And then it became clear…

The footage was haunting and unforgettable. And so I set off to meet the people involved…

Here’s the details for the January 15th screening.

And here’s a shot of the mountain:

Jon

November 2, 2014

Virgin Galactic and Burt Rutan

Last year I wrote a really long piece about Virgin Galactic for The Guardian. The most relevant parts of it - given that terrible crash on Friday - relate to Burt Rutan and Scaled Composites. It was a Scaled test pilot who was killed. Burt Rutan almost never gives interviews but he gave me one. So I thought I’d isolate those parts here If you want to read the whole thing it’s:

***

When our interview is over, I drive out of the Mojave Space Port towards Los Angeles. I pass the spot where, on a boiling hot afternoon – 26 July 2007 – Rutan’s team was testing rocket propellant for Virgin Galactic when a tank of nitrous oxide exploded. There had been 17 people watching the test out here in the desert, this place for maverick engineers to push the boundaries. Shards of carbon fibre shot into them. Three of Rutan’s engineers were killed, and three others seriously injured.

"It turned Burt Rutan from a young man into an old man overnight," Branson told me. "He’d never lost anybody in his life."

Rutan’s company was found liable and fined $25,870. As the science writer Jeff Hecht wrote in New Scientist, “The company has an enviable reputation for creativity, but the report suggests it did not have an obsession with training, rules and written procedures… a dangerous combination when working with rocket fuels.”

Rutan quit the business in 2011. He retired to the lakes of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, a climate about as far from Mojave as is possible to find. He didn’t respond to my emails asking for an interview.

When I asked Branson how personally connected he felt to the three deaths, he said, “Well…” Then he stopped. “If they were working directly for me, I would feel very responsible. Obviously, if we hadn’t decided to do the programme in the first place, they would be alive today. So you realise that. But talking to relatives and survivors – I think every one of the survivors came back to work with the rocket company afterwards. Everybody had to pick themselves up and move forwards, and everybody did.”

Two weeks later I receive an email I hadn’t expected at all: “I am in Buenos Aires on vacation. I will be at home in Idaho on Saturday and happy to talk to you after that.”

It is Burt Rutan.

I call him the day his cruise docks – this semi-reclusive engineering genius. I say that future generations might regard him as the Brunel of democratised space travel; does he think about things like that?

"Only since my retirement…" he says. He’s got a rich, deep American-South voice. Then he tells me why all this began for him.

"In the mid-60s, a friend of mine, Mike Adams, got killed during a re-entry." They had been stationed together at the Edwards Air Force base in Lancaster, California, when Adams, test flying an experimental suborbital plane called the X-15, “didn’t line the angles up. He was killed because the requirement to do a precision re-entry had not been met.”

Adams’s death stayed with Burt, he says, even when he left the air force and set up business in a hangar at the Mojave airport, designing prototype planes. “It was just a deserted old second world war training airport in a crummy little desert town. I had a family, which I lost mainly because I was a workaholic.” He says most aerospace engineers work on an average of two-and-a-half planes during their whole careers. He was building one every year, “without ever injuring a test pilot. You can’t have more fun than a first flight when you find out if your friend lives or dies flying it. And I flew six first flights myself. With a tiny crew of three dozen people who worked their asses off.”

He says you won’t find his inventions in the big airliners – the Boeings and Airbuses. They’re overly risk-averse and conservative, which is why their planes look identical. But the private jet companies have embraced his creations – planes such as the Beech Starship. And throughout it all he brooded over the death of Mike Adams and wondered how he might invent “carefree re-entry”.

He says there was no great Eureka moment with his shuttlecock idea. But one day he felt confident enough to approach Paul Allen and say, ” ’I would now put my own money into it if I had the money.’ And he put out his hand and we had a handshake. That was the extent of the begging for money I did for SpaceShipOne. He gave me several million dollars and said, ‘Here. Get going.’”

"What’s Paul Allen like?" I ask.

"Opposite of Sir Richard," Burt replies. "I could call Sir Richard while he’s sleeping at home in Necker island and chat with him. We debate global warming fraud all the time."

"Hang on," I say. "Which of you thinks it’s a fraud?"

"He thinks it exists; I think it stopped 17 years ago," Rutan replies. "Anyway. Paul Allen’s own people can’t just walk into his office. They schedule a meeting a couple of weeks in advance. On the few occasions I was alone with Paul, his own people would rush up to me and go, ‘What did he say?’ But if he says something, everybody listens, because it’s an important thing to be said.”

Between 2001 and 2003, SpaceShipOne was a covert endeavour. Nobody outside Burt’s weather-beaten hangar knew they were “developing all the elements of an entire manned space programme. We developed the launch airplane, the White Knight. We developed our own rocket engine, and a rocket test facility, and the navigation system that the pilot looks at to steer it into space. We built a simulator. And, of course, we built SpaceShipOne and trained the astronauts. In 2004, we flew three of the entire world’s five space flights – funded not by a government but by a billionaire who made software. This private little thing. Later, people said I must have had help from Nasa. I didn’t want Nasa to know. And they didn’t.”

Since then, Rutan says, history has proved his shuttlecock mechanism to be foolproof. “People told me it would go into an unrecoverable flat spin, but I knew in my gut it would work. And it worked perfectly the first time and every time. It has never had to be tweaked or modified. Which is crazy, because it’s so bizarre.”

Any delays these past 10 years, he says, have been due to the complexity of the rocket motor design and the fact that Virgin Galactic is full of “smart people” – by which he means committees: interior design committees, PR committees, safety committees. He sounds a bit rueful about this, like if they had listened to him, it could all have gone a lot faster.

He doesn’t mention the accident. I’m not relishing asking him about it, because I’m sure it was the worst day of his life, but when I do, he immediately says, “Sure, I’ll talk about that.”

He won’t go into its cause much – only that it was a “very routine” test that fell victim to “a combination of some very unusual things”. He pauses. “All of us would be bolt upright at two in the morning for a while after that.” And even though he was 220 miles from the explosion, the shock almost killed him, too. “My health deteriorated to where I could almost not walk. I just seemed to get weaker and weaker every day.” He says that if I saw pictures from the unveiling of SpaceShipTwo at the Museum of Natural History in New York that following January, I’d see a man “incapable of walking up three or four steps”. (I do see those pictures later and he does looks terrible.) Eventually his condition was diagnosed as constrictive pericarditis – a hardening of the sac around the heart. He says that as an engineer he can’t bring himself to believe that the stress of the accident hardened a membrane: “That wouldn’t make sense.” But his wife is convinced of it.

At the end of our conversation, Rutan suddenly says, “If there’s an industrial accident at a corporation and three people are killed and three people are seriously injured, how often is there a lawsuit where the families sue the company?”

"Almost every time," I say.

"There was none," he says. "There was none. We wrapped ourselves in the families. We told them the truth from the start. None of them sued us. Each of those families is a friend of the company. And that has a lot to say about something that I’m most proud of in my career, and that is how to run a business from an ethical standpoint."

Later, I look at the memorial website for one of the men who died, Eric Dean Blackwell. It is maintained by his wife, Kim. At the bottom there’s a link to Virgin Galactic, so people can read updates on how the programme is progressing.

September 28, 2014

An Evening of Public Shaming...

If you would like to be the very first people to hear about my forthcoming book on public shaming (out March 2015), I’m workshopping the talk in Brooklyn and London:

October 9th, 2014

Union Hall, Brooklyn

http://www.unionhallny.com/event/678827

***

October 18th, 2014

Frieze Art Fair, London.

http://www.friezeprojects.org/talks/detail/jon-ronson-an-afternoon-of-public-shaming/

***

October 19th, 2014: MATINEE and November 7th 2014 EVENING

An Afternoon/Evening of Public Shaming.

Invisible Dot, London

Details coming.

December 14, 2013

From The Psychopath Test

I felt differently about Bob’s checklist now. I now felt that the checklist was a powerful and intoxicating weapon that was capable of inflicting terrible damage if placed in the wrong hands. I was beginning to suspect that my hands might be the wrong hands.

December 13, 2013

Psychopath Night

Tomorrow night is Psychopath Night on Channel 4. If it’s all about psychopath spotting for fun, that’s bad. But there’s something worse. Which is when people with authority over people’s lives succumb to power trips and confirmation bias. Here’s a paragraph from my book The Psychopath Test:

“I do worry about the PCL-R being misused,” Bob said.

He let out a sigh, stirred the ice around in his drink.

"In the U.S. we have the Sexually Violent Predator Civil Commitment stuff. They can apply to have sexual offenders ‘civilly committed.’ That means forever… .”

Bob was referring to mental hospitals like Coalinga, a vast, pretty, 1.2-million-square-foot facility near Monterey Beach, California. The place has 320 acres of manicured lawns and gyms and baseball fields and music and art rooms. One thousand five hundred of California’s one hundred thousand pedophiles are housed there, in comfort, almost certainly until the day they die (only thirteen have ever been released since the place opened in 2005). These 1,500 men were told on the day of their release from jail that they’d been deemed re-offending certainties and were being sent to Coalinga instead of being freed.

“PCL-R plays a role in that,” said Bob. “I tried to train some of the people who administer it. They were sitting around, twiddling their thumbs, rolling their eyes, doodling, cutting their fingernails—these were people who were going to use it.”

A Coalinga psychiatrist, Michael Freer, told the Los Angeles Times in 2007 that more than a third of Coalinga “individuals” (as the inmates there are called) had been misdiagnosed as violent predators, and would in fact pose no threat to the public if released.

“They did their time, and suddenly they are picked up again and shipped off to a state hospital for essentially an indeterminate period of time,” Freer told the newspaper. “To get out they have to demonstrate that they are no longer a risk, which can be a very high standard. So, yeah, they do have grounds to be very upset.”

December 12, 2013

FRANK STORY talks and other talks

June 3rd and Thereafter The First Tuesday Of Every Month Until One Of Us Gets Deported:

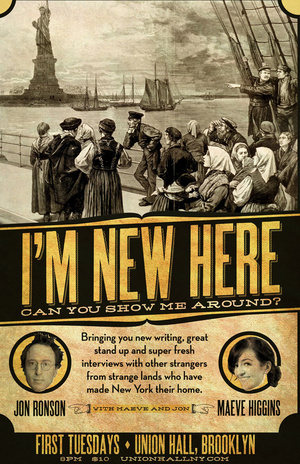

I’M NEW HERE - CAN YOU SHOW ME AROUND?

A Monthly Show at Union Hall, Brooklyn, on how the Immigration is Going

Sometimes the only thing to do is to move to New York City. So you do it. You take a deep breath, you move here, you take a look around and you breathe out. That exhale might sound like a terrified scream, or a delighted giggle. Who knows? Jon Ronson does! Maeve Higgins does! Two funny people – Jon Ronson (writer, showgirl) and Maeve Higgins (comedian, legend) bring you new writing, great stand up and super fresh interviews with other strangers from strange lands who have made New York their home.

Tickets: http://www.unionhallny.com/event/579079-im-new-here-can-you-show-me-brooklyn/

June 11th A NIGHT OF ANIMAL MADNESS WITH JON RONSON AND LAUREL BRAITMAN

Tickets: http://www.thebellhouseny.com/event/5...

July 17th. 5x15. Wilton’s Music Hall, London. A Frank talk.

July 18th: Latitude Festival. A Frank talk.

http://www.latitudefestival.com/

July 19th: Chapter, Cardiff. A Frank talk.

July 20th: Llangollen Festival. A Frank talk.

http://www.llangollenfringe.co.uk/index.php/en/festival-2014/40-jon-ronson-frank-story

July 21st Dukes Theatre Lancaster. A Frank talk.

http://www.dukes-lancaster.org/event/jon-ronsons-frank-story

July 22nd: Trades Club Hebden Bridge. A Psychopath talk.

http://www.ents24.com/hebden-bridge-events/the-trades-club/jon-ronson/3810346

July 23rd Dancehouse, Manchester. Back by popular demand. With fill Frank Sidebottom Oh Blimey Band! Last ever Frank talk (unless I do one in New York).

Tickets: https://dancehouse.ticketline.co.uk/order/tickets/13294826

October 4, 2013

My Gladwell film

Oh: people who can’t watch iPlayer, my Gladwell film (made in September 2013) has gone up on You Tube…

Part 1 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LktwDI6JqO0 …

July 25, 2013

the switch in psychopaths' brains

There’s a piece on the BBC website today talking about how neuroscientists have discovered that ‘psychopathic criminals have an empathy switch’ that they can turn on and off at will.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-23431793

I’m always a bit suspicious of any study that comes from an fMRI machine, because every fMRI person I ever spoke to gave me a massive lecture on how the brain works and ended it with “but of course we have no idea how the brain works”.

Anyway, this morning I got an email from the man who wrote me this long ‘email from a psychopath’ back in 2011:

http://jonathanronson.tumblr.com/post/43313551453/an-email-from-a-psychopath

His new one is short but interesting, so here it is with his permission (I’m not going to copy emails from psychopaths without their permission):

I came across this today on the BBC - to me this makes infinitely more sense than most of the literature that’s out there. I’m not sure its a cut-and-dry ‘switch’ though, that seems a little too robotic to be sensible.

I remember describing it in therapy as ‘speaking a second language’; you can do it, and if you practice enough you can become quite fluent, but it usually takes a lot of energy and its easy to slip back, which is why the ‘psychopath charm’ is often thought so contrived and calculated.

In my view, once empathy starts to deliver practical benefits to the individual (rather than being totally at odds with every aspect of ones life) psychopaths can genuinely be helped. In other words, its hard to learn Mongolian in Brooklyn; you have to immerse yourself in the language, both to become proficient, and for it to seem purposeful to the student that they do so.

Best

C

July 18, 2013

Upcoming talks 2016Jan 26th - Jan 30th 2016: Leicester Square Theatre, LondonA different story each...

Upcoming talks 2016

Jan 26th - Jan 30th 2016: Leicester Square Theatre, London

A different story each night, with special guests. I’ll do some kind of monologue each night. It’ll be funny. I’ll show clips. And then I’ll bring on the special guests.

Jan 26th: LOUIS NIGHT special guest - Louis Theroux (sold out)

I’ve never done anything with Louis before. It’s really overdue and I’m very excited. Louis and I will talk about the times our research has intersected - in Neo-Nazi compounds and with the KKK and about mental health labeling. We’ll talk about my books Them and The Psychopath Test and Louis’ documentaries about Aryan Nations and Coalinga, A Place for Paedophiles amongst other things.

Jan 27th: SHAME NIGHT special guests - Bridget Christie and Charlie Gilmour (sold out)

This night will be all about my book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed. Charlie will tell his amazing story of judicial and prison shaming. And Bridget will talk about the systemic shaming of women by misogynists. And it will be very funny although it may not sound like it will.

Jan 28th: THEM NIGHT special guest TBA (sold out)

I don’t know who the special guest will be yet. But this is THEM night. THEM began as a book about different kinds of extremists, but after I’d got to know some Islamic fundamentalists, neo-Nazis and Ku Klux Klan members, I found that they had one belief in common: that a tiny elite, which meets in secret, determines the course of global events. My quest to locate these secret rulers of the world was extremely hazardous. I was chased by men in dark glasses, unmasked as a Jew in the middle of a Jihad training camp, and witnessed international CEOs and politicians participate in a bizarre pagan ritual in the forests of Northern California.

Jan 29th: LOST AT SEA NIGHT special guest Adam Buxton (sold out)

As Adam puts it, this night will be about “two neurotic men trying to understand and empathize with their fellow humans, grown ups with hang ups in charge of children, and who look back on previous versions of themselves with a mixture of regret and shame”. Adam will be performing his own stuff and I will be telling stories from my domestic life and from my book Lost at Sea.

Jan 30th: PSYCHOPATH NIGHT special guests Mary Turner Thomson and Eleanor Longden (sold out)

My Radio 4 documentaries about Mary and Eleanor are my two favourites. Neither Mary nor Eleanor appear in my book The Psychopath Test but the book wouldn’t exist without them. I’m being oblique because I don’t want to spoil the twists in their stories. If you don’t know who they are don’t Google them. The less you know the better. I’ll also be telling the story of The Psychopath Test.

Jan 31st: The Oxford Union, Oxford (in association with Blackwell’s Oxford)

This is an early evening event - 5pm - only £2 and free to Oxford Union members.

Feb 4th: Glasgow Royal Concert Hall

Feb 5th: Chapter Arts Center, Cardiff

Feb 10th: I’m New Here, the monthly show I curate with Maeve Higgins, Union Hall, Brooklyn

LISA KRON, writer of FUN HOME, is one of our guests! She’s so great.

February 23rd: Distinguished Lecture Series, Madison, Wisconsin

Jon Ronson's Blog

- Jon Ronson's profile

- 5708 followers