Jon Ronson's Blog, page 7

July 18, 2013

Talks

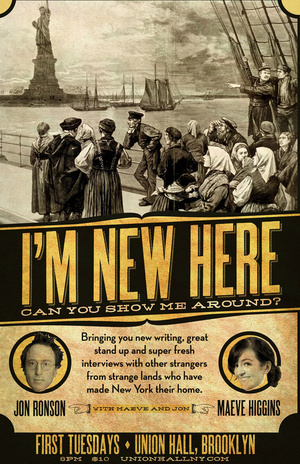

August 10 2014 and Thereafter The First Tuesday Of Every Month Until One Of Us Gets Deported:

I’M NEW HERE - CAN YOU SHOW ME AROUND?

A Monthly Show at Union Hall, Brooklyn, on how the Immigration is Going

Sometimes the only thing to do is to move to New York City. So you do it. You take a deep breath, you move here, you take a look around and you breathe out. That exhale might sound like a terrified scream, or a delighted giggle. Who knows? Jon Ronson does! Maeve Higgins does! Two funny people – Jon Ronson (writer, showgirl) and Maeve Higgins (comedian, legend) bring you new writing, great stand up and super fresh interviews with other strangers from strange lands who have made New York their home.

http://www.ticketfly.com/purchase/event/628953

August 15th: Landmark Sunshine theatre, New York.

I’ll be doing Q&As after the 6.45pm and 7.15pm showings of Frank and introducing the 9pm and 9.30pm showings.

http://www.landmarktheatres.com/market/NewYork/SunshineCinema.htm

August 18th: TEDx talk, Martha’s Vineyard

http://tedxmarthasvineyard.com/schedule/

August 21st: The Morbid Anatomy Museum, Brooklyn

A new monthly series: The Morbid Anatomy Museum will be showing rare screenings of the highlights of Jon’s documentary career, with a talk and a Q&A by Jon after each one.

July 9, 2013

the death of Paul O Brien

When I was researching the story Lost at Sea about Rebecca Coriam, who went missing on the Disney Wonder, I heard the Lynsey O Brien story. This is what I wrote at the time:

*

‘“There’s a man in Ireland had a 15-year-old daughter,” Carver said. “One cruise served her eight drinks in an hour. She went to the balcony and threw up and went overboard. She was gone.”

The case he’s talking about is that of Lynsey O’Brien, who went missing on 5 January 2006 while on a cruise with her family off the Mexican coast. The cruise line, Costa Magica, conducted its own investigation into her disappearance and decided there was “no evidence of an accidental fall”, that Lynsey had shown the bartender ID stating that she was 23 years old and that her death was caused by “underage drinking”. While they “continued to extend their deepest sympathy” to the family, they claimed their report cleared them of any wrongdoing.

"In other corporations, police get involved," Carver said. "On cruise ships they have, quote, security officers, but they work for the cruise lines. They aren’t going to do anything when the lines get sued. We came to the conclusion cover-up is the standard operating procedure.” He paused. “And the Coriam girl. Where is the CCTV footage?”

*

Last September Lynsey’s father Paul emailed me because he’d written a book he was going to self-publish about his daughter:

"My book is not about making money it’s about stopping the horrors that’s happening on board these cruise ships. What myself and mike lost no money can replace. The book should be out next week in America and I will forward you all the links. If you want me to email you a proof I can, so you can read the extent of losing a child has on the mind”

*

Mike Coriam just emailed me to say that Paul has been found dead. From today’s Irish Independent:

*

The last line of his email to me haunted me at the time and does again now, especially when you remember what kind of investigations take place when someone goes missing from a cruise ship.

Here’s my full Lost At Sea story:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2011/nov/11/rebecca-coriam-lost-at-sea

May 9, 2013

May 2013 BOOK TOUR dates, UK and US

Hello. BOOK TOUR!

May 19th:

School of Life, London. But it’s sold out already.

May 19th:

Sunday Wise at the Ivy, London

https://sunday-wise.myshopify.com/collections/frontpage/products/sunday-wise-may

But this is a fancy boutique thing and it is expensive and I’m one of many speakers, so I’ll only be speaking for a few minutes. But it does look good.

May 21st:

Dublin Writer’s Festival http://www.dublinwritersfestival.com/event/jon-ronson

(talking about Lost at Sea and The Psychopath Test)

May 22nd:

Derry-Londonderry festival (In Derry. Or Londonderry.)

http://www.cityofculture2013.com/event/jon-ronson-in-conversation-with-michael-bradley/

May 23rd:

Bookslam, London

http://bookslam.com/events/96/book-slam

May 24th:

Cardiff Central Library

http://www.thesprout.co.uk/en/events/jon-ronson-ctral-library/07113.html

May 25th:

Hay Festival

(talking about Lost at Sea and The Psychopath Test)

https://www.hayfestival.com/p-5838-jon-ronson.aspx

May 26th:

Sunday Papers Live London

http://www.sundaypaperslive.com/#!books/c1kbd

May 31 - June 2nd:

MaxFunCon, Lake Arrowhead, California

June/July/August:

Sitting alone in a room until…

Weekend of August 10th/11th:

Wilderness Festival in the Cotswolds

http://www.wildernessfestival.com/

August 18th:

EDINBURGH!

March 5, 2013

A conversation I had with Justin Bieber

This was three years ago. The story I wrote wasn’t so great, but this part might help explain him turning up two hours late last night.

“Does all the travel make you feel lost?” I ask.

"You’re so far away," he nods, "and you start feeling like you’re a robot. When I’m overseas the schedule is always crazy and then there’s the time change and you’re not even yourself. It’s weird."

"Do you ever feel wistful for the days before you were famous?" I ask.

At this Justin looks as if it’s all getting too introspective. “I’m a regular person,” he says hurriedly. “I’m living my dream and I’m just enjoying every minute of it.”

He shrugs as if to apologise for the downbeat, pensive tenor of the interview. He says I should be glad I’ve not got him on a bad day.

"Mike knows my bad days," he says.

"Act out what you’re like on a bad day," I say.

"OK. Ask me a question," he says.

"What do you think of that sofa?" I say.

Justin gives me a look of boredom tinged with withering hatred: “I like it,” he mutters. “Next question.” He gazes off into the distance.

A chill runs through me. “Thank God you’re not having a bad day today,” I say.

"I’ll be zoning off," he says. "I’ll be over there. I’ll not be focused on you. Good days I’ll be…" Justin leans over until he’s an inch from my face. He gives me a vast and petrifying smile.

February 18, 2013

A final picture from the man who buys White Albums

A final picture from the man who buys White Albums

February 17, 2013

An email from a psychopath

For the people who ask me if I ever get emails from psychopaths (reprinted with his permission):

message: Dear Jon,

I just saw your interview on Australia’s ABC 7:30 report on ‘The Psychopath Test’ and wanted to share my experience. I hope that it can remain confidential for the time being, seeing as it is quite personal.

But, when I was 19 (I’m 26-27 now) I went into long-term therapy - for psychopathy.

My case was rather unusual in that I self-referred. The mental health agency had not had a walk-in of this kind before. In the lead up, I had found myself becoming overwhelmed with a predatorial instinct that I could not shake - I’d sit, watching crowds of people go by, driven to mania by what I saw as their limitless inferiorities. Plans were set that, once enacted, would be very difficult to walk back from.

Nevertheless, the decision to go to therapy was one I had taken with some considerable agony, given that I saw this as putting myself ‘on the radar’ so to speak, and thus making it considerably more difficult to ‘act out my nature’ as I saw it.

I undertook a lengthy psychological examination, and the psychiatrist conducting it wrote some pretty stark conclusions devoid of any optimistic prognosis.

My initial forays into therapy did not go well. Overwhelmed with mistrust, concerned at being maniuplated, and uncomfortable with the idea of being ‘managed’ rather than ‘cured’, I left on multiple occassions for some periods of time.

After chewing through several therapists, the director of the agency finally took me on herself, and to our mutual surprise we got along extremely well.

To make a long story short, after years of setbacks, frustrations, resentments and suspicion, I began to make considerable progress.

Four years later, with sessions no less frequent than once or twice a week, I came out of therapy unrecognizable from when I went into it.

Yes thearapy was transformative, though it is possible to overstate its impacts. I will always see the world through different lenses to much of the rest of the world. My emotional reactions are different, my endowments are impressive in some respects, not so in others, much like other people.

It is also the case that, being ‘normal’ takes a degree of energy and conscious thought that is instinctive for most, but to me is a significant expenditure of energy. I think it analogous to speaking a second language. That is not to say I am being false or obfuscating, merely that I will always expose some eccentric traits.

So why am I writing all this to you?

Well, from someone who is both psychopathic and treated, there are many fallacies about psychopaths with which I am deeply cynical. Unfortunately psychopaths themselves do themselves no favors, as the label given to them plays into their ego over generously - ‘If we are born that way’ psychopaths reason, ‘then it is not wrong for us to be as we are, indeed we are the pinnacle of the human condition, something other people demonize merely to explain their fitful fears’.

We are neither the cartoon evil serial killers, nor the ‘its your boss’ CEO’s always chasing profit at the expense of everyone else. While we are both of those things, it is a sad caricature of itself.

We continue be to characterized that way, by media, by literature, and by ourselves, yet the whole thing is a sham.

The truth is much, much more complex, and in my view, interesting.

Psychopaths are just people. You are right to say that psychopaths hate weakness, they will attempt to conceal anything that might present as a vulnerability. The test of their self-superiority is their ability to rapidly find weaknesses in others, and to exploit it to its fullest potential.

But that is not to say that this aspect of a psychopaths world view cannot be modified. These days I see weaknesses and vulnerabilities as simple facts - a facet of the human condition and the frailties and imperfections inheritent in being human.

At the same time it is true that my feelings and reactions to those around me are different - not necessarily retarded - just different. It is the image of psychopaths as something not quite human, along with espersions as to their natures, that prevent this from being identified.

So how to explain these ‘different’ feelings?

Well, lets look at what (bright) psychopaths are naturally quite exceptional at… We are good at identifying, very rapidly, extreme traits of those around us which allows us to discern vulnerabilities, frailties, and mental conditions. It also makes psychopaths supreme manipulators, for they can mimick human emotions they do not feel, play on these emotions and extract concessions.

But what are these traits really? - Stripped of its pejorative adjectives and mean application, it is a highly trained perception, ability to adapt, and a lack of judgment borne of pragmatic and flexible moral reasoning.

What I’m saying here is that although those traits can very easily (even instinctively) lead to dangerous levels of manipulation, they do not have to.

These days I enjoy a reputation of being someone of intense understanding and observation with a keen strategic instinct. I know where those traits come from, yet I have made the conscious choice to use them for the betterment of friends, aquaintences, and society. People confide in me extraordinary things because they know, no matter what, I will not be judging them.

I do so because I know I have that choice. After years of therapy I am well equipped to act on it, and my keen perception is now directed equally towards myself.

Its true that I do not ‘feel’ guilt or remorse, except to the extent that it affects me directly, but I do feel other emotions, which do not have adequate words of description, but nevertheless cause me to derive satisfacton in developing interpersonal relationships, contributing to society, and being gentle as well as assertive.

Such as statement might tempt you to say ‘well obviously you’re not a real psychopath then’. As if the definition of a psychopath is someone who exploits others for their personal power, satisfaction or gain.

A slightly more benign (but still highly inaccurate) definition is that a psychopath is someone who feels little guilt or empathy for others.

In the end, psychopaths need to be given that very thing everyone believes they lack for others, empathy; a willingness to understand the person, their drives, hopes, strengths and fears, along with knowledge of their own personal sadnesses and sense of inferiority…As it is, such cartoon, unchangeable, inhuman characterizations offers nothing but perpetuation of those stereotypes.

Serial Killers & Ruthless CEOs exist - Voldemort does not.

Thank you,

C

One Cut

So I wrote a true story about one public sector cut and what happened next. I’m publishing it just here, nowhere else. Here it is:

This is the story of one cut. Back in October 2010 George Osborne announced £95 billion in cuts to public services, saying he’d leave it to councils to choose what to shut down. Inevitably most of the casualties ended up being unrenowned places, unlikely to stir up much protest - drop-in centers in housing estates, inner-city park rangers, community theatres, etc. I wanted to write about just one of them, about the ripples created by a single closure. I made my selection quite randomly. I chose a place called Youthreach. I didn’t know much about them, only that they offered weekly counseling sessions to young people, aged 11–25, in Greenwich, South East London.

April 8th 2011.

Today is the day the Youthreach counselors learn their fate. They knew the council was slashing their funding, but they hoped it might be by 40%, and maybe they could solicit donations from local businesses. But in fact they’re being cut by 100%. £118,000 a year. So it’s over.

“How long before you close?” I ask them.

“Eleven weeks,” says Maria Day, their director. “We’ve been here 25 years and in eleven weeks it’ll be gone.”

We’re sitting in the staff-room, which is nice and brightly decorated. Youthreach is a unit in a row of shops on Delacourt Road.

“What do you think will happen to the kids?” I ask.

“We’re not mind readers,” says one of the therapists, a little sharply, from across the room. “We’re not fortune tellers.”

There’s a cold silence. One of the volunteer counselors explains that many of them had, as children, been helped by places like Youthreach, and now their chance to do the same for others is being snatched away from them.

“We can’t pass them onto anyone,” says Maria. “There’s only one counselor at Family Action. And they mainly just take sexual abuse cases. It’s really narrow.”

Maria says she’ll put the word around, inviting the kids to contact me once the place closes so I can document their post-Youthreach lives.

June 30th.

I log onto Youthreach’s website. It reads ‘Not Found – 404’. Then the emails start coming in.

I don’t hear from the girl Maria had told me about who lives with her mother and “only leaves the house to come to counseling. It takes her so long to psych herself up and get ready sometimes she only comes for five minutes.” But I hear from a dozen others.

There’s Emily, 20: ‘The problem I have with guilt is actually at an extreme level and it interferes with every part of my life. A lot of my thought processes are extremely flawed, which is why counseling helped. I can realize they’re flawed if I’m removed from them. The lows – the urge to self-harm – are more persistent again.’

There’s Grace, 16: ‘I really seriously majorly spilt every single one of my thoughts out onto this counseling guy for 10 months, then I just had to say bye.’

There’s Helen, 21: ‘I had my last counseling session on Wednesday. Since then I have been put BACK on anti-depressants, signed off sick from work, and am generally at a very low point. Normally I would be looking to discuss this with my counselor on Wednesday.’

These are people who, if they had a spare £100 a week, could go private. But they don’t. Maria had told me that a typical Youthreach person was not an offender (a lot of Young Offender support teams are being cut around the country) but the opposite: “They care too much, and usually about other people and not themselves.”

July 15th.

I arrange to meet Alicia at the Starbucks near the Cutty Sark, Greenwich. I spot her right away. We order. I get a muffin. She has herb tea.

Alicia was a classic Youthreach person in that she was very sick but just okay enough – measurably okay enough - to not qualify for help from the NHS. It started a year ago, she says. Before that everything was perfectly normal. But then she split up from her boyfriend of five years.

“I was a bit depressed,” she says. ”I didn’t eat a lot. I noticed I’d lost weight and I liked it. So I started going to the gym every day. I’d run to the gym, spend an hour there, and run back. I remember eating half an apple, and I was completely bloated, I couldn’t eat any more.”

“You were 20 then?” I ask.

“Yes, I’m 21 now,” she says. “I started throwing up. I had panic attacks. I lost my fertility. I felt really angry when people told me how thin I was. I thought they were just trying to get me fat. I was, ‘How dare they?’ I got down to five-and-a-half stone, nearly five stone.”

Which was when her mother convinced her to see her GP.

“They did some blood tests,” she says. “They came back on the borderline of okay. I wasn’t so bad that I was nearly dying, so they said they wouldn’t do anything about it unless I went to an institute and internalized myself.”

I’m curious about what the “borderline of okay” means. So later, after I leave Alicia, I call the NHS. They explain that with eating disorders the blood tests are designed to measure the electrolyte - the minerals. When you fall below a certain level a set of NHS protocols click into place. You’re diagnosed, labeled, and offered out-patient care. It’s the same with anxiety disorders. If your anxiety coalesces into something that has a label – OCD, or whatever – there’s procedure. You’re automatically referred to a cognitive behavioral therapist. But if your anxiety swirls amorphously around, label-less, you can fall through the NHS cracks.

That’s where Youthreach used to come in. They were there for the troubled but unlabeled.

“I loved Youthreach,” says Alicia. “I didn’t have to worry about being judged. My counselor made me feel normal at a time when I wasn’t normal in my head.”

Alicia says she’ll be fine. They closed down just as she had got well enough to not need them any more: “I had to get to seven stone for everything to be all right. I’m just over seven stone now. When I went to Youthreach all I wanted was a boyfriend. Now I’m completely the opposite. I’m fine on my own and I keep having to turn people away. But if they’d closed down when I was worse…” She pauses. “I just feel for those people.”

August 9th.

Emily and I arrange to meet at a coffee place in Lewisham. When she walks in she seems like the sort of person you’d assume to be having a great life – young, good looking, Camden-market-type clothes. But then she sits down and starts talking and what comes out is a loop of devastating anxiety. Her brain is all over the place.

She says she’s been suffering her whole life, but the recent big spiral, the one that took her to Youthreach, began in December 2010. She’d left home for University, found she couldn’t handle it, so returned home and got a job in the council offices. One day last December she was at work when she failed to recognize someone she should have. “My eyesight isn’t very good and I’m not very good at facial recognition,” she explains. “She had a proper go at me in the lift.”

So Emily decided to kill herself.

“Because someone shouted at you in the lift?” I ask.

“It made me think, ‘I clearly can’t function in society,’” says Emily. “Throughout my teenage years I was constantly worried about that. I’d been diagnosed with Asperger’s as a child and had a statement of special needs and hated it. I didn’t want to be dependent on other people all my life, but now I was thinking, ‘Here’s the evidence that I can’t cope in society.”

So Emily went down to a railway track. Nothing happened. Some passers-by quickly talked her out of it. The Greenwich NHS determined that - like Alicia with her blood tests - she wasn’t quite bad enough for the Maudsley Hospital: “I don’t meet the criteria because I’m functioning. I’m not at risk at the moment of hurting myself or others.”

So instead she went to Youthreach.

“It was an enormous relief,” says Emily. “Obviously it wasn’t going to make all my issues suddenly vanish because they’re to do with the way I think. But, seriously, it felt really good.”

And then Youthreach closed down.

Emily pushes her shortbread around her plate and tells me about how one irrational thought snakes it’s way around all the other irrational thoughts. The words come too quickly out of her mouth. There’s the riots: “I’m addicted to rolling news, which is literally the worst addiction you can have if you have anxiety problems. I got really on edge and I couldn’t sleep and I couldn’t concentrate.”

There’s the fear of cancer: “Everyone jokes about hypochondria. With me it literally takes over my life. I can spend pretty much all day worried I have cancer.”

There’s the social anxiety: “I get paranoid about everyone I know being in this huge conspiracy against me. This gives me rashes so I become convinced I have septicemia. I manage to tire myself out so I hit a depressed stage. The other day someone told me to cheer up and I felt suicidal for the first time in six or seven months.”

She finally falls silent. We’re both exhausted. “I realize my thought processes are extremely flawed,” she says. Then she shrugs to say, ‘But what can you do?’

“I’ve always wanted to stand up on stage and be a singer, but that’s not going to happen,” she says. “I’m young. I’m supposed to be reckless, doing stupid things, having fun. And I can’t.”

She points at her brain, and just manages to stop herself from bursting into tears.

Over the next few weeks I meet other Youthreachers cast adrift. There’s sixteen-year-old Grace, whose fights with her mother have spiraled so epically she’s decided to leave home and move in with a friend: “She’d say, ‘Take a coat.’ I’d say, ‘Mum, I don’t need a coat.’ ‘Yes, you do.’ ‘Blargh!’ It explodes from the smallest thing.”

And Grace does leave home, in September: ‘It is ok but then again it has only been 4 weeks haha,’ her new roommate, a school-friend of hers, emails. ‘It may get a bit more annoying as she is sleeping in my room, haha.’

But I must admit I’m only half-engaging with Grace’s problems because I’m so worried about Emily. Grace seems basically fine – self-assured, strong-willed. Emily struck me as a mess, like a scared passenger in the runaway train of her thought process. Weeks pass before she answers my emails, and when she does write back the emails sound worrying: ‘Sorry, I’ve been massively out of it for about a week or so.’

She writes that her suicidal thoughts have started again: “I used to think it was normal to make all these elaborate plans about killing yourself. When I was seventeen I’d go to train stations and seriously contemplate jumping. Then, when I started going to Youthreach, I realized it wasn’t normal. But now the lows are persistent again.” She says she’s started daydreaming elaborate suicide plans: “In one plan, to mitigate the effects on my family, I completely estrange myself from them and then pretend I’m missing. I don’t leave a note. And I make it look like an accident, so they don’t blame themselves. It’s disturbing to be thinking about it in that sort of depth.”

She says she’s decided to enroll again in University, even though she doesn’t hold out much hope. She picks one in the North of England. We agree that I’ll visit her there in a month to see how she’s getting on.

October 17th.

Emily and I have arranged to meet in the Student Union, but I can’t see her anywhere. It crosses my mind that things are so bad she’s forgotten about it. But then I see her walking towards me, giving me a small, low, surreptitious wave.

We find a corner. And she starts to talk. Like at the coffee shop in Lewisham the words seem to be coming out too fast. But that’s the only similarity between the two meetings. She is, amazingly, having a really great time.

“Remember I told you how I always liked the idea of being a singer,” she says. “Well the other night I did it for the first time, at a coffee shop in town. I’d planned on completely bombing and I’d never have to sing in public again. But it went REALLY well. I got loads of applause. One of the organizers has offered me a regular slot there.”

She smiles, with happy bewilderment. “I’m really quite overwhelmed at the moment,” she says.

“You’re like a different person,” I say.

“Yeah, yeah,” she says. It’s just really bizarre.”

“Is there nothing bad to tell me at all?” I ask.

She pauses for a second. “I can’t really think of any bad stuff,” she says. “There were some stupid interpersonal dramas in the first week but funnily enough I handled them all right. I locked horns with a few people. A lot of the students are Conservative. Instead of thinking, ‘Oh, I AM weird,’ it was, ‘Screw you. You’re wrong.’”

“So it turns out you can function in society,” I say.

“Yeah,” she says. “And also, no one knows!”

“No one knows what?” I ask.

“No one knows I’m autistic!” she says. “So I’m generally feeling quite good about things. I was worried you’d be disappointed that I’m doing so well! But it is genuinely so weird to not have all this stuff going on in your head all the time.” She pauses. “I honestly don’t believe I’d have done any of this if it wasn’t for Youthreach.”

She shows me a text from her mother. It was sent in the aftermath of her successful singing performance. It reads, ‘Hey, you sound so confident and you really know what you’re doing.’

She says she’s going to start volunteering in town, helping kids who are suffering from anxiety and depression.

November 22nd.

I send a final email around to everyone to say my story is nearly finished and do they have any last minute updates about their lives. Emily emails back right away. Things have got even better. ‘Weeeeeell. I have a boyfriend? We started seeing each other a few weeks ago. I really like him. Also I got a first in my first assessed essay for university. Spoke to my seminar leader about it and she said it was the highest mark she gave.’

I hear from Grace’s friend – the girl she moved in with: ‘The living together is good,’ she writes. ‘We get on.’

Then Alicia emails. She says there’s no updates in her life, only that she ‘may have just landed a main role in To Kill A Mockingbird, so everything career wise is going really well! Unfortunately I am having issues with my health, weight, body image. I know of course it won’t ever fully disappear but seeing as I’m not at my worst state, I am not eligible for help from the doctors, and seeing as services such as Youthreach have been taken away, there is no help.’

I email back to ask what she weighs now.

‘I don’t weigh myself because it kind of only spurs things on a bit more,’ she replies, ‘but last time I did, I was about 6 and three quarters stone.’

Then she adds: ‘So weird to hear from you as I was thinking about Youthreach all of last night! I had one of those evenings where I did really miss my counselor. I was trying to think up of ways to thank her. It used to be so nice to have someone to talk to every week.’

Julie Burchill and Psychopaths

Hello,

Whenever someone comes onto the TV or the radio sounding like a psychopath I get tweets asking me if they are one. I also get offers to be a talking head on TV. I always say no because whilst it would be nice to make hay while the sun shone, it’s quite morally corrosive (not to mention massively unethical) to diagnose someone off the TV.

I tell you who would be even more unethical than me if they went on TV to diagnose someone from afar as a psychopath: any forensic psychiatrist or psychologist or anyone who works in that field as an expert.

The Psychopath Test is a cautionary tale to not do that, in fact. It’s as much a book about confirmation bias as it is about psychopaths. (By the way, ever since I learnt about confirmation bias I’ve started seeing it everywhere.)

When I started writing The Psychopath Test - http://jonronson.com/psycho.html - I read THIS BOOK diagnosing Lyndon Johnson from afar as bipolar: http://www.amazon.com/Power-Beyond-Reason-Collapse-Johnson/dp/1569802432

It might be right for all I know. Maybe Lyndon Johnson WAS bipolar. But I’d never read a less likable book. It was so high and mighty. So ivory tower. So reductive. And so from afar. And so I vowed never to do that. So in The Psychopath Test I only ever recount conversations with people I met for the book. That way all the ambiguities and nuances, the biases, the power play between the interviewer and interviewee, would be part of the writing.

Anyway, I was thinking about all of this listening to Julie Burchill on Desert Island Discs this morning. At times she could not have sounded more textbook Hare Checklist.

JB: “I think I was born without something. It’s not something I put on, hand on my heart, it’s something I feel. Maybe I was born with something missing. But if I was I’m glad I was because I don’t want to be one of those people who creep around trying to get people’s approval. i think they’re pathetic.”

KY: “I don’t believe you. I think you do care.”

JB “I’d like to say you were right and it would make me sound a better person and a more rounded person. But I can’t lie to you …You’re a nice civilised person. But I’m not like you …I’ve always been a show off, I’ve always been to some extent shameless, and I’ve always been an agggressive person. Not physically but the way I think and the way I go after other people.”

Here’s one tweet I read just after she said this:

'Julie Burchill is demonstrating psychopathy so clearly on #desertislanddiscs that I might use it as a teaching tool for my students.'

I know what she meant. You only have to read the the checklist:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hare_Psychopathy_Checklist#The_two_factors

Anyway, a few minutes later JB is talking very movingly and sincerely about missing her parents, and how much pain she would feel going back to Bristol because the accent would remind her of them:

"If I was in Bristol and everywhere I turned someone would be going, ‘all right my lover’, I’d feel sad and I’d really miss them." And, "If I was blubbing at every person who opened their mouth it would be weak and silly. I’d be acting like a nincompoop. I know myself really well and I know that’s how I’d behave so it’s best to keep out of harm’s way."

I noticed that I felt weirdly disappointed for a moment when she said this. I wanted the one aspect of her personality - the psychopathic-sounding one - to be more true and significant. I had to kind of force myself out of one train of thought into another.

I think this is part of the reason why there are so many miscarriages of justice in the psychopath-spotting field. Here’s a paragraph from The Psychopath Test:

'Bob Hare told me of an alarming world of globe-trotting experts, forensic psychologists, criminal profilers, traveling the planet armed with nothing much more than a Certificate of Attendance, just like the one I had. These people might have influence inside parole hearings, death penalty hearings, serial-killer incident rooms, and on and on. I think he saw his checklist as something pure – innocent as only science can be – but the humans who administered it as masses of weird prejudices and crazy dispositions.'

Psychopaths (whatever you want to call them) exist. I believe in the veracity of the Hare Checklist. I believe Hare is right. And I think that psychopaths can be - maybe always are - terrible malevolent forces. And I totally sympathise with anyone who gets caught up with one. But Desert Island Discs reminded me of something my friend Adam Curtis said to me when I was writing my book: “It’s not easy to truly know another person.”

Jon Ronson's Blog

- Jon Ronson's profile

- 5708 followers