Rod Dreher's Blog, page 668

September 10, 2015

‘What’s Theirs is Yours’

Ray and Dorothy Dreher, Spring 2012

A couple of years ago, at the first Walker Percy Weekend, Tracie Barnard and her husband came down from Tennessee for the event. They were fans of The Little Way of Ruthie Leming. I invited them to come over for a gumbo lunch at my house on that Saturday. They sat on the same front porch on the book’s cover with my folks, Mam and Paw, and talked. Tracie recalls that day in a very moving blog post paying tribute to my dad, who died last month. (See the post I wrote about the day of his death here). Excerpt from Tracie’s entry:

Paw was especially proud of Hannah, Ruthie and Mike’s eldest daughter, who was then backpacking through Europe. He told me I should look up her blog! He relaxed in his easy chair, reclined back. You could tell he had once been an invincible man of the land. Ruthie’s journey had taken its toll on him. His eyes were bright–but you could see his broken heart in them. He spoke sweetly, gently, of his girl. He said that he had read the book–Mam hadn’t made her way through as yet. What struck me is that some of the stories she told of Ruthie–her fishing excursion after her diagnosis, “the halo picture” (those of you have read the book know precisely of what I speak), Rod had shared in “The Little Way”. I listened, often laughing through teary-eyes. Mam, my friends, is a vibrant woman, full of fun and mischief. My kind of woman.

We shared bowls of gumbo, styrofoam cups of hospitality, and a heap of gratitude. We found the chance to tell them just how much this book had meant to us, to the cadre of friends with whom we had shared it (some of whom received it as a graduation gift!), and the impact of Ruthie’s life, her Way, had made on folks she never met. I could barely get the words out–and my dearest Philosopher paused, gathering himself, as he expressed his appreciation. As Rod helped his daddy out to the front porch (for his “smokes”), Mam said quietly, “Ray isn’t meant for this world much longer. A part of him died with Ruthie. I just pray that the Lord takes him quickly.”

We decided to take our leave, thanking our gracious hosts along the way. Rod hugged us and thanked us for spending time with his folks. Absolutely no thanks were necessary. My goodness. I was full–of nourishment undefinable. I asked Mam if we could take a picture on the rocking chair. And, she said, “Of course, Honey.” She sat, I knelt down beside her, both of us smiling–and “glistening” in the heat of the day. We hugged, I planted a little smooch on Paw’s rugged cheek, squeezed his hand, and thanked him quietly. So much like my Pop-Pop, ever the gentleman, he thanked us again for coming. And waved from his spot on the porch.

Oh my heart.

Read the whole thing. It got to me, I’ll tell you that. Thank you, Tracie. See you next week in Tennessee.

Benedict, Beer, Douthat, Decline

I’ve written a lot in this space about how much I love the Benedictine monks of Norcia, who have created a fastness of light, beauty, and grace in the Umbrian mountains, over the childhood home of Saints Benedict and Scholastica. What they are doing in their monastery is spiritual and cultural work that is vital to all of us. I’m sure of it. Making a pilgrimage last fall to Norcia to pray where St. Benedict lives, and where the traditional Latin liturgy is chanted, was one of the highlights of my life. Here is the monastery website, where you can learn more about them, including their first-ever album of chant. They also do something there that’s unusual for Benedictines in Italy: they brew beer!

Well, I’ve learned that next month, on October 7, there will be an event in New York City to raise funds for the Norcia monastery. The speaker will be Ross Douthat, whose talk is titled, Religion and the Fate of the West: Being Catholic in a Secular Age. Father Cassian Folsom, the prior of the Norcia monastery, will also be there; he’ll be talking about the work of the monastery and its role in restoring Christianity. Fr. Cassian is bringing with him some of the delicious beer he and his men brew.

I wish it were possible for me to be there. I know, like, and respect both men very much. I am not overstating things when I say that I think of them and their work as important to the future of Christianity in the West. The idea of Ross and Fr. Cassian meeting delights me. The idea of both of them speaking at the same venue about the faith, culture, and living it out in the post-Christian West is really about as good and evening of thinking and fellowship as this Benedict Opter can imagine.

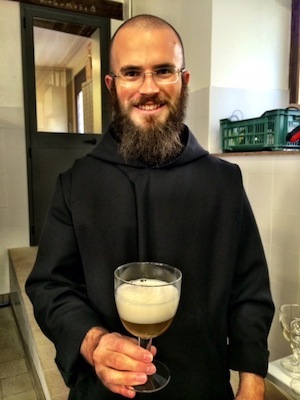

Fr. Martin, brewmaster

And I don’t overstate things when I say that Birra Nursia is very good stuff. The commercial clip at the top of this post gives you a brief view of what life is like in the monastery, and also at its tiny brewery. I’ve been to both places, and let me tell you, it’s graced, all of it.

If you are a Christian who lives in or around New York City, I exhort you to buy an advance ticket and go hear Fr. Cassian and Ross talk. Tickets aren’t cheap, but the money is for a good cause — that precious monastery — and I can all but guarantee it will be worth it. I especially urge any young Catholic men who think they might have a vocation to the monastic life to go listen to and meet Fr. Cassian. It could change your life.

More info and ticket purchases here.

Interior of monastery refectory, Norcia

Livy and the Bishops

A conservative Catholic reader passes along this disheartening (to say the least) piece from the National Catholic Reporter. Excerpts:

Dying of cancer, Bishop Emeritus Geoffrey Robinson appeared Aug. 24 before the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse to testify to the prevalence of child sexual abuse in the church.

He painted a sad picture of a brave and lonely Sisyphus with his band of bishops in tow, pushing a boulder with a reasoned response to the crisis up the Vatican Hill, only to have it pushed back by popes and cardinals who had no idea about the issue and a blindness about the incapacity of canon law to deal with it.

“However great the faults of the Australian bishops have been over the last 30 years, it still remains true that the major obstacle to a better response from the church has been the Vatican,” Robinson told the commission. Most of the Roman Curia saw the problem as a “moral one: if a priest offends, he should repent; if he repents, he should be forgiven and restored to his position. … They basically saw the sin as a sexual one, and did not show great understanding of the abuse of power involved or the harm done to the victims.”

More:

In his perceptive notes of the meeting in the Vatican in April 2000 to discuss child sexual abuse, Robinson wrote that the members of the Roman Curia showed an “an overriding concern to preserve the legal structures already in place in the Church and not to make exceptions to them unless this was absolutely necessary.”

He told the Commission how Italian Archbishop Mario Pompedda told the delegates how they might get around canon law, but he did not want a law that he had to get around. He wanted one he could follow, but “they never came up with it.” Robinson came away from that meeting knowing that the Australian bishops had no choice but to continue to go it alone, irrespective of what the fall out might be.

The extent to which he and the other Australian bishops were prepared to do that is starkly illustrated in the minutes of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference of Nov. 28, 2002, where they resolved to disobey Pope John Paul II’s 2001 Motu Proprio, Sacramentorum Sanctitatis Tutela, which required all complaints of child sexual abuse to be referred to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith which would then instruct the bishop what to do. They would only refer those cases where there was no admission by the priest that the abuse had occurred. Robinson told the Commission that the purpose behind that was to avoid being told by Rome what to do with those priests who admitted the abuse. That decision was well justified given the figures presented to the United Nations by the Vatican that only one third of priests against whom credible allegations of child sexual abuse had been made, have been dismissed. The claim that the Vatican has a policy of zero tolerance is pure spin.

Read the whole thing. Bishop Robinson is a theological liberal who has called for the Roman Catholic Church to chuck all its traditional teachings on sexuality. It’s important to say that one does not have to agree with him here (I certainly do not) to recognize that the bishop may be telling the truth about the way the Church bureaucracy has handled — and mishandled — this crisis over the years. I’m strongly inclined to believe that he is.

One of the most profound and difficult lessons I learned from writing about the Scandal was that the theological orientation of a particular bishop or priest — liberal, conservative, etc. — was in no way a reliable guide to whether or not that cleric could be trusted to do the right thing on the matter of clerical sex abuse. My point is that if you are inclined to dismiss Bishop Robinson’s testimony solely because he’s a heterodox liberal, you’re making a mistake.

This essay hit me in a particular way, coming on a day and a week in which I’ve been thinking a great deal about the passing away of the Christian West. It hardly needs remarking that the Church in Europe has very nearly collapsed, and that the abuse scandal — something that arose within the Church, and that was perpetuated by the Church — has a lot to do with its failure in Ireland. The reasons for Europe’s loss of faith in Christianity, both in its Protestant and Catholic versions, are many and complex. Still, it is not that difficult to imagine fallen-away Europeans Catholics, as well as unbelievers, would shut the door decisively to the possibility of reversion or conversion, because of the continuing inability of the Church’s authorities to come to terms with the abuse.

One is reminded of the Roman historian Livy’s famous remark about the beginning of Rome’s decline: “We can endure neither our vices nor the remedies for them.”

The other day on this blog, my friend and faithful reader James C., a traditionalist Catholic living in England, reacted with anger to a statement by the French bishops saying that French Catholics ought to open their arms to the refugees without distinction, because to do otherwise would be “totally contrary to the spirit of religions.” James called them “spineless, useless masses of episcopal jelly” — a very Raspailian diagnosis, in fact.

I have said before here that none of us Westerners outside the Catholic Church can afford to take pleasure in her troubles, or to be indifferent to them, because as goes the Roman church — the foundation of Western civilization since the end of antiquity — so go we all. When I read things like Bishop Robinson’s testimony to the Australian government commission, side by side with statements like that of the French bishops, I have a lot of thoughts and emotions, none of them hopeful or pleasant. After all this time, I am still capable of being scandalized by the death-wish of the hierarchy. Forget serving the interests of Christ; they don’t seem capable of even serving the interests of themselves.

Many Syrias To Come

A reader posted a powerfully executed graphic story explaining Syria’s collapse as primarily (but not entirely) as a result of global warming. How did that happen? From 2006 to 2011, Syria experienced a catastrophic drought, an event so off-the-charts that it can’t be explained by normal climate variations. The drought forced farmers and rural folks off of their land and into the cities, which put a tremendous strain on infrastructure, as well as water and food supplies. Eventually that resulted in protest against the Assad regime. You know the rest.

Many people on the American right don’t believe in global warming. The Pentagon is not among them. In July of this year, those crazy liberals at the Defense Department submitted to Congress a report outlining the primary ways it expects global warming to affect the global security environment. Excerpt:

Persistently recurring conditions such as flooding, drought, and higher temperatures increase the strain on fragile states and vulnerable populations by dampening economic activity and burdening public health through loss of agriculture and electricity production, the change in known infectious disease patterns and the rise of new ones, and increases in respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. This could result in increased intra- and inter-state migration, and generate other negative effects on human security. For example, from 2006-2011, a severe multi-year drought affected Syria and contributed to massive agriculture failures and population displacements. Large movements of rural dwellers to city centers coincided with the presence of large numbers of Iraqi refugees in Syrian cities, effectively overwhelming institutional capacity to respond constructively to the changing service demands. These kinds of impacts in regions around the world could necessitate greater DoD involvement in the provision of humanitarian assistance and other aid.

More frequent and/or more severe extreme weather events that may require substantial involvement of DoD units, personnel, and assets in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) abroad and in Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) at home. Massive flooding in Pakistan in 2010 was the country’s worst in recorded history, killing more than 2,000 people and affecting 18 million; DoD delivered humanitarian relief to otherwise inaccessible areas.

Syria is not a one-off thing, and it’s not something that can be blamed entirely on radical Islam, on Assad’s dictatorship, on US meddling, and on Iran — though all of those play a part. In 2006, long after Iraq was falling apart, I interviewed one of the world’s top experts on Syria, who explained why, for various reasons, the same thing would not happen to Syria.

That was the year the drought started in Syria. And now look. If you take a look at this page, and click on the “overall vulnerability” button, it will show you a global, color-coded map indicating which countries are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change — in terms of extreme weather, sea level rise, and loss of agricultural productivity. The most imperiled nations are those of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, including China and the Indian subcontinent — that is, the parts of the world where most of the population lives.

If I were Vladimir Putin, I would worry far less about Ukraine, and far more about defending the Russian Far East from Chinese climate refugees later this century.

How is Europe going to defend itself against mass migration from Africa and Asia caused by famine and wars sparked by famine? Like, say, the Syrian war?

This is just the beginning of the troubles.

Regional Novels, Explained

Reader Liam sends in some pretty great literary comedy from The Toast. Here’s a sampling from Mallory Ortberg’s distillation of Every Southern Gothic Novel Ever:

5. Why, This House Represents The Last Vestige Of A Grandeur This Town Could Never Hope To Regain, And We Wouldn’t Sell It For The World

8. No One Listens To What Old Pap’s Got To Say, On Account Of This Deformity, But I Say It’s You All What Has The Deformity, In Your Souls, I Knows What I’ve Seen

12. I Drink Because This House Is Filthy And All The Servants Have Fled

13. Someone Is Going To Have To Shoot The Dog Before It Reaches The Courthouse

And here’s a selection from her list of Every New England Novel Ever:

6. Don’t Sit In That Chair, Boy; Your Mother Sat In That Chair Once And Look Where It Got Her

8. Brisk Ten-Mile Walks Are The Only Medicine Or Therapy This Family Needs

9. The Cod Have Returned

10. Not Everything In Yon Churchyard Is Asleep

17. An Outsider Is Rebuffed

Tidbits from Every Californian Novel Ever:

10. This Pool, Like L.A. Society, Is Only Reflective On The Surface And Also Lacks Depth

11. The 1960s Are Upon Us At Last

12. How Can You Develop Character In A State Without Winter?

13. Everyone Sits In Their Cars, Moving In The Same Direction But Unable To Touch: A Description Of Traffic But Also Of Life

14. The Film Industry Is Corrupt

Entries from Every Scottish Novel Ever:

8. This Rugged, Rocky Landscape Has Shaped Our Hardscrabble Souls In A Way This Soft-Handed Londoner Could Never Hope To Understand

16. In The Long-Running Battle Between Guilt And Desire, Guilt Wins Out

17. Painting Your Shutters Is For Papists And Sexual Deviants; Whitewash Is Good Enough For The Likes Of Us

My favorite of them all is the Southern Gothic line about the dog and the courthouse.

Here’s something else funny from The Toast, sent in by a reader with appalling taste in football teams (she’s from Alabama, naturellement): Dante running into Beatrice in art history.

Is Christianity A Suicide Cult?

In last night’s bedtime reading of The Camp of the Saints, I had to wade through the muck of Chapter 20, which was pretty much a matter of racialist pornography, describing life aboard the migrant flotilla as nothing more than eating, defecating, and screwing, like an undifferentiated mass of animals. It was repugnant. But then, with the remains of that steaming cowpile fresh on my shoes, I ran across this diamond:

Two opposing camps. One still believes. One doesn’t. The one that still has faith will move mountains. That’s the side that will win. Deadly doubt has destroyed all incentive in the other. That’s the side that will lose.

The next few chapters describe nations that took firm action to protect themselves from being colonized by the migrants. Australia made it clear that they would not be allowed to make landfall. Egypt fired warning shots off the bow of the lead ship, which caused the flotilla to turn from Suez and take the long way around Africa. The South African government — remember, this is set in the era of apartheid — announced that it would be prepared to sink the flotilla before letting it land. This gave the world the opportunity to pile on the condemnation of the Afrikaners, which it took.

The fleet steams on toward Europe.

Last night’s reading is a perfect example of why this novel is both appalling and riveting. (I keep making that point because I’ve never read anything like it, with the possible exception of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, and it’s an unusual experience). Raspail, it seems to me, is deadly accurate in his diagnosis of the sentimental humanitarianism of the Europeans, and how their loss of faith in their own civilization compels them to behave in ways that guarantee its destruction by an invading force. The novel also implicitly raises a disturbing question: What cruelties, if any, are justified for the sake of a nation’s defense?

These are extremely complex, morally harrowing questions, and we are seeing them on display now as Europe faces its refugee crisis. The very best thing I’ve read yet about the potential Christian response to this crisis comes from Alastair Roberts, a British Christian. His piece is somewhat long, but it’s well worth your time and consideration. Excerpts:

The response to the refugee crisis has been troubling, exposing the depth of the rot of Europe’s psyche. Both in European societies and governments and within the Church it has also revealed just how impoverished our moral and political discourse actually is. For the difficult tasks of patient deliberation and discriminating political wisdom, a cult of sentimental humanitarianism–Neoliberalism’s good cop to its bad cop of foreign military interventionism–substitutes the self-congratulatory ease of kneejerk emotional judgments, assuming that the ‘right’–what ought to be done–is immediately apparent from some instinctive apprehension of the ‘good’.

In the febrile environment of social media, this cult of sentimental humanitarianism frequently manifests in virtue-signalling and policing and in immense waves of collective emotion. Declaring definitively, yet thoughtlessly, upon issues of labyrinthine complexity, it regularly appears to involve a narcissistic preoccupation with our own caring, not least relative to the supposedly inadequate caring of others. The simplistic vision that would cast fiendishly knotty social and political problems as if they were parable scenes for us to re-enact for our moral self-validation is bankrupt. As Daniel Hannan and Matthew Parris both observe, our fetishization of sentiment has an obfuscating effect, and neglects the actual task of prudence that lies before us. It leaves us ill-equipped to recognize how involved matters are, runs the risk of encouraging counterproductive responses, and can produce cynical and opportunistic political leadership. Melanie McDonagh also draws attention to the capriciousness and irresponsibility of sentimentalist politics, driven as it is by unpredictable surges of common public feeling in reaction to emotionally affecting images. The images that enflame our sentimentalism are shorn of the sort of historical and political context that might prevent them from functioning as screens upon which Europe projects the theatre of its own tortured psyche.

More:

Pascal Bruckner and others have commented upon Europe’s self-reproaching tendencies, our perverse urge to blame the West for all of the wrongs of the world, to project upon the poor and disenfranchised the character of innocent victims, and to view alignment with them as our one chance at psychic redemption. Many of these groups are all too happy opportunistically to play the part of the wronged party to whom we are morally indebted.

Bruckner writes of Europe: ‘Ruminating on its past abominations–wars, religious persecutions, slavery, imperialism, fascism, communism–it views its history as nothing more than a long series of massacres and sackings that led to two world wars, that is, to an enthusiastic suicide.’ The exhaustion of Europe’s cultural spirit is seen in such phenomena as the bland narcissistic hedonism of our liberal utopias and in our inability to reproduce ourselves. The looming demographic crisis that faces Europe’s greying populations produces a need for cheap foreign labour that needs to be seen as part of the story behind differing responses to the refugee crisis (why are we so welcoming of mass asylum when we cannot even welcome our own offspring into the world?). One of the reasons why Islamophobia is a real phenomenon in Europe is because it is so unsettlingly apparent that, as Michael Houellebecq intimates, the young Muslim immigrants entering Europe have a vitality and virility of cultural spirit that is alien to native Europeans.

Raspail: Two opposing camps. One still believes. One doesn’t. The one that still has faith will move mountains. That’s the side that will win. Deadly doubt has destroyed all incentive in the other. That’s the side that will lose.

One more clip from Roberts, who says that as Christians, we certainly have an obligation to show charity to refugees, but that does not mean that we are morally obligated to allow them to settle among us:

Liberalism’s undervaluation of particularity encourages it to think in terms of abstract right-bearers and of mere space. The paradigmatic person of liberalism is a displaced one: the universal human subject. As one might expect, the result of the liberal vision has often been the breaking down of particular communities and places into interchangeable territories, rendering all increasingly ‘placeless’, both in the social, historical, and material order.

The indiscriminate welcoming of migrant populations can attenuate place for everyone. Although this may serve the interests of capitalists and governments who stand to benefit from a mobile, dependent, and biddable workforce and a population with little internal solidarity, this is at heavy cost to the wellbeing of the people within such groups. The persons who bear the heaviest burden of this loss of place are typically the poorest within society.

As Paul Kahn has argued, the liberal vision of political community as founded upon the formality of social contract and around universal human values and rights, neglects the reality that every such community must be bound together by the forces of sacrifice, of faith, love, and identity, forces that are inescapably particular. Peoples and places are forged around shared customs, values, religions, languages, histories, cultural canons, symbols, and sacrifices and it is only thus that universal human goods are realized.

The biblical vision of charity ‘begins at home’, with those who are our immediate neighbours, and with the principled extension of our places to others–or the creation of new shared places–in a manner that preserves and develops their character as specific refractions of universal human goods. Although this extension is and should be transformative, the particular is never abandoned for the universal, however.

To welcome masses of migrants is to run the risk of sinning against the neighbor one already has. It is also to run the extreme risk of sacrificing the community itself by dissipating the non-rational forces — sacrifice, faith, love, identity — that bind a community together.

Read the whole thing. Roberts offers his own suggestions for how European Christians should respond faithfully to the refugee crisis. Raspail would probably think him too soft, but I think he’s on to something. Nevertheless, Roberts grasps Raspail’s essential point: that Europe’s self-loathing, faithlessness (in God, in itself), and its sentimental humanitarianism, which substitutes emoting for the difficult task of thinking, are going to destroy it.

So, again: Raspail can be repulsive, but he wrote about something real, something that’s happening right now. People like the prominent left-wing Anglican priest Giles Fraser could have come straight out of The Camp of the Saints. Fraser writes, in (where else?) The Guardian:

For years our politicians have piggy-backed upon Christian morality for electoral advantage. We should “feel proud that this is a Christian country”, said Cameron earlier this year (pre-election, of course), in what some might uncharitably see as a call to maintain a Muslim-free view from his Cotswold village. But there is no respectable Christian argument for fortress Europe, surrounded by a new iron curtain of razor wire to keep poor, dark-skinned people out. Indeed, the moral framework that our prime minister so frequently references – and to which he claims some sort of vague allegiance – is crystal clear about the absolute priority of our obligation to refugees.

It’s easy to say that Fraser is full of it. It’s much more difficult to say what seemingly hard-hearted actions Europeans should be prepared to take, or have taken in their name, to prevent the colonization of their countries and the long-term destruction of their way of life. One of the most unsettling thoughts provoked by Raspail’s novel is that the kind of people who will do whatever is necessary to preserve their civilization are the kind of people who regard people from the Third World as Raspail does in Chapter 20: as an undifferentiated mass of people who are barely human. In which case one wonders whether one has preserved civilization at all.

Hard, hard questions…

September 9, 2015

Actually, That Poem Sounds Better in Chinese

Michael Derrick Hudson is an ordinary vanilla white dude from the Midwest who couldn’t get his poems published under his own name. Then he adopted a pen name, Yi-Fen Chou, and promptly

Hudson, who is white, wrote in his bio for the anthology that he chose the Chinese-sounding nom de plume after “The Bees” was rejected by 40 different journals when submitted under his real name. He figured that the poem might have a better shot at publication if it was written by somebody else.

“If this indeed is one of the best American poems of 2015, it took quite a bit of effort to get it into print, but I’m nothing if not persistent,” reads his unabashed explanation.

Anecdotally, Hudson’s calculation was correct. The literary journal Prairie Schooner, one of nine places to receive a submission from “Yi-Fen Chou,” accepted “The Bees” and three other poems for its Fall 2014 issue. The poem was referred to Best American Poetry, where Alexie came across it, and wound up in the collection, where Brooklyn-based writer and snarky Tumblr poetry-commentator Jim Behrle found it and posted it to his site.

Ah, but the Social Justice Warriors of the Diversity-Industrial Complex are not taking this lying down:

“When you’re doing this from a position of entitlement, you’re appropriating an ethnic identity that’s one, imaginary, and two, doesn’t have access to the literary world,” poet and Chapman University professor Victoria Chang told The Washington Post. “And it diminishes categorically all of our accomplishments. He sort of implies that minorities are published because we’re minorities, not because of our work. That’s just insulting because it strips everything we’ve worked so hard for.”

But, um, Prof. Chang, Sherman Alexie, the (Native American) writer who chose the poem for the anthology, admitted that he gave it extra credit for being from an ethnic Chinese writer. You can’t have it both ways.

Actually, you can, and you will, because when it comes to diversity in academia, heads diversocrats win, tails fairness and merit lose.

Vilsbergism In Our Time

I continue to make my way through Jean Raspail’s dystopic 1973 novel, The Camp of the Saints, and I continue to be appalled at times by its racialism, but more than that, astonished by the prescience with which Raspail diagnosed the cultural malaise that prevents the Europeans from defending their civilization. Reading this thing — available here in English translation on PDF — is like reading the newspaper today.

The novel is about a mass exodus of Third Worlders to Europe, seeking not the culture of the West, but its wealth and opportunity. In this passage, Raspail fictionalizes how the professional classes in France prepare the masses to accept the imminent arrival of one million immigrants from India, traveling in a giant boat convoy. “Vilsberg” is an influential commenter on French radio; “Machefer” is a reactionary old journalist listening to Vilsberg’s broadcast. Here’s the passage:

Out of the radio, slow and calm, came Vilsberg’s voice:

“As I read and listen to the first reports and comments on the Ganges armada, and its staggering exodus westward, I’m struck by the depth of human feeling that seems to pervade them all, and the candid appeals for a wholehearted welcome. Indeed, have we time for a choice? But through it all, one thing appalls me: the fact that nobody yet has pointed to the danger, the risk inherent in the white man’s meager numbers, and his utter vulnerability as a result.

“I’m white. White and Western. So are you. But what do we amount to in the

aggregate? Some seven hundred million souls, most of us packed into Europe, as against the billions and billions of nonwhites, so many we can’t even keep up the count. In the past we could manage some kind of a balance, more precarious daily. But now, as this fleet heads toward our shores, it seems to be saying that, like it or not, the time for ignoring the Third World is past. How will we answer?

What will we do? Are these the questions you’re asking yourselves? I hope so. It’s high time you did!”

“There, the work’s cut out!” Machefer broke in, over Vilsberg’s voice. “The usual bear hug! Nice and clear. Right up close. Enough to scare their pants off. Now, if only he’d go the next step, and tell them to shoot, tell them to blast the crowd to hell! But no! Not our Vilsberg!”

“I can tell,” Vilsberg continued, “that you really don’t believe how serious the situation is. After all, we lived side by side with the Third World, convinced that our hermetic coexistence, our global segregation, would last forever. What a deadly illusion! Now we see that the Third World is a great unbridled mass, obeying only those impulsive urges that well up when millions of hapless wills come together in the grip of despair. More than once in the past, from Bandung to Addis Ababa, attempts to organize and mobilize that mass had failed.

“But today, since morning, we’re witnessing a mighty surge, seeing it take shape, for once, and roll on. And nothing — nothing, take my word — is going to stop it! We’re going to have to come to terms … But again, I can tell, you don’t really believe me. You’d rather not think. It’s a long, long way from the Ganges to Europe. Maybe our country won’t get involved. Maybe the Western nations will come up with a miracle just in time. … Well, you’re welcome to close your eyes and hope. But later, when you open them up, if you find a million dark-skinned refugees swarming ashore, tell me, what will you do? Of course, we’re merely supposing, granted. All right then, let’s suppose some more.”

“Now watch, kiddies,” Machefer interjected, “here comes the pirouette!”

“As long as we’re at it, let’s assume that we’re going to take in these wanderers. Yes, like it or not, cordial or begrudging, we’re going to take them in. We have no choice. Unless, that is, we want to kill them all, or put them away in camps. Perhaps we have forty days left, perhaps two months at best, before their peaceful and bloodless invasion. That’s why I want to suggest, in this time for conjecture, that we all do our utmost to accept the idea, to grow used to the thought of living side by side with human beings who seem to be so different from ourselves.

“And so, I’m inviting you all to join us here on RTZ, beginning tomorrow, at this same time each day, for our new, forty-five-minute feature, ‘Armada Special.’ We’ll try to answer your questions frankly, all the questions you’ll be asking yourselves — and us — about how a million refugees, fresh from the Ganges, can live together, in harmony and understanding, with fifty-two million Frenchmen. I say ‘we,’ because, happily, Rosemonde Real has agreed to join me in this staggering task. You know her well for her perceptive thinking, her passion for life, her trust in mankind, her profound awareness of the human soul and its innermost workings …”

“Good God, not her again!” Machefer exclaimed. “Isn’t there anything that hag won’t do to get on the air?”

“Needless to say, we won’t be alone. Rosemonde and I have spared no effort to bring in specialists from every field to answer your questions: doctors, sociologists, teachers, economists, anthropologists, priests, historians, journalists, industrialists, administrators … Of course, I don’t claim that we’ll have all the answers. Certain more delicate problems—perhaps in the sexual or psychological realms — certain problems that strike at the heart of that lingering racism present in us all, may demand more thought and more specialized experts. But we promise to strive for the truth, as the sensible, clearheaded people we hope we are, and we trust that we’ll find the truth worthy of you, and of us.

“Later, when all is said and done, at the end of the gripping adventure begun this morning on the banks of the Ganges, if not one single hopeless wretch has come our way, then we, the public, will simply have played in the greatest radio game in history: the antiracism game. And believe me, we won’t have been playing in vain! At least we’ll have played for the honor of mankind.

“Then too, who knows but what, in some dim, distant future, we may have to play it again, and for keeps? … And now, until tomorrow, good night …”

One of the most disturbing things about this novel is that the only people (so far) who have any instinct to object are people like Machefer, who are crude and more or less racist. Later, there is a caller to Vilsberg’s radio show, a Monsieur Hamadura, a native-born Indian who once served as a French colonial official. The hosts think he will be calling to support the armada, but in fact he phones as a defender of Western values to tell the French that they’re making a big mistake. Vilsberg and Rosamonde cut him off, and tell their listeners that Hamadura is a sad case of a self-hater who has allowed his mind to be colonized.

The Camp of the Saints, as you will have heard, has been embraced by white nationalists, and even worse. The reason I never read it was precisely because of that fact. It’s a mistake not to read this book, though. It is easy enough to sift out the nasty aspects of Raspail’s book. Louis-Ferdinand Céline was a vicious anti-Semite, but he also wrote important books. Look at this from the New Yorker:

“Céline is my Proust!” Philip Roth once said. “Even if his anti-Semitism made him an abject, intolerable person. To read him, I have to suspend my Jewish conscience, but I do it, because anti-Semitism isn’t at the heart of his books… . Céline is a great liberator.” Louis-Ferdinand Céline was born on this day in 1894. He was a French writer largely remembered for his first novel “Journey to the End of the Night,” a loosely biographical work teeming with disease, misanthropy, and dark comedy. He was decorated for bravery in the First World War, and wrote anti-Semitic pamphlets in the run-up to the Second, after which he was declared a national disgrace and imprisoned for collaborationist sympathies. Céline, in short, is one of the great problems in twentieth-century literature: you find yourself irresistibly drawn in by the fearless singularity of his vision, even while aware of the appalling place to which it led him. What’s striking is how absent his grievous opinions are from his great novels where one can occasionally glimpse a gentle humanist buried beneath a bitterly stung idealism.

I cite that to underline the point that we shouldn’t reflexively dismiss The Camp of the Saints because we may find Raspail’s views objectionable in part. Racism is not at the heart of this book, at least I haven’t found it to be so yet (I’m one-third of the way through it). It is a book about the West, and the limits of humanitarianism. Is liberalism a suicide pact? Raspail’s point of view is that post-Christian liberalism has convinced contemporary Europeans that theirs is not a civilization worth defending.

To me, one of the most disturbing things about the book is that the only people who seem to believe in defending France, and in French civilization, are characters most of us would find distasteful at best. As I go through the novel, I see more clearly why, in our own time, the only people who dare to talk about these things are people who often hold unpleasant or outright offensive views. By demonizing all discourse critical of multiculturalism, though, elites and mainstream enforcers of elite opinion risk empowering the kind of far-right people who aren’t interested in the niceties of democratic pluralism.

What brought this passage from the novel to mind was this report, from The Guardian, posted by James C.:

The first 200 refugees arrived in France from Munich today, as France prepares to bus 1,000 Syrians, Iraqis and Eritreans from Germany this week, writes our Paris correspondent Angelique Chrisafis.

But there has been controversy after some French town-halls said they would take only Christian refugees.

This week, the mayor of Roanne, who belongs to Nicolas Sarkozy’s right-wing party Les Républicains, said he would only accept Christian Syrians so he could “be absolutely certan that they aren’t terrorists in disguise.” Then the mayor of Belfort, from the same party, responded to the government’s appeal for towns to house refugees saying his town would take only Christian Iraqi or Christian Syrian families “because they are the most persecuted.”

Last night, the town council of Charvieu-Chavagneux near Lyon said it would only take a Christian family because Christians “don’t put people’s security in danger.”

The government reacted furiously. The Socialist prime minister Manuel Valls said: “We don’t select on the basis of religion. The right to asylum is a universal right.” The interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve said it would be “macabre” to make a distinction by religion. The French Bishops’ Conference said distinguishing a person’s faith would be “totally contrary to the spirit of religions”.

In his speech today EU president Jean-Claude Juncker urged Europe not to make religious distinctions about refugees. He said: “Europe has made make the mistake in the past of distinguishing between Jews, Christians, Muslims. There is no religion, no belief, no philosophy when it comes to refugees.”

And this also from the same source:

But there is debate in France about public opposition to taking more refugees. A poll conducted by Odoxa for Le Parisien, after the images of the drowned 3-year-old boy Alan Kurdi had shocked the world, found that a majority of French people, 55%, were opposed to France acting in the same way as Germany by loosening its conditions for refugee status. A total of 62% of French people felt those fleeing Syria should be treated as migrants like any others. Only 36% felt Syrians should be given a better welcome as refugees from war.

The historian Benjamin Stora, who heads the board of France’s Museum of the History of Immigration, warned that the reasons for French public reticence went beyond France’s current economic crisis and millions of unemployed. Writing in Le Monde, he argued that far-right ideology had permeated debate in the country and more must be done to reverse negative stereotypes in France, which was historically a country that had welcomed asylum-seekers.

Why is it unreasonable for a country traumatized by the Charlie Hebdo attacks, a country that just awarded the Legion d’Honneur to three Americans who thwarted Islamist mass murder on a TGV last month, to have extreme doubts about mass resettlement of Muslim refugees? The instant demonization of that point of view by politicians, academics, bishops, and others, rendering it inadmissible for public discussion, is Vilsbergism, tout court.

Should French voters — who plainly do not want what the elites are foisting upon them in this crisis — one day elect a Front National government, Vilsbergism will have played a role in bringing about that unhappy result.

Kim Davis: Shipwreck of Religious Liberty

Finally, someone — in this case, Rasmussen — has done a poll to find out what the American people think about the Kim Davis case. The results:

But just 26% of Likely U.S. Voters think an elected official should be able to a ignore a federal court ruling that he or she disagrees with for religious reasons. The latest Rasmussen Reports national telephone survey finds that 66% think the official should carry out the law as the federal court has interpreted it.

You have to be a Rasmussen Reports subscriber to get more detail than that, but consider that three out of four Americans believe Kim Davis was wrong to refuse obey the Supreme Court. It’s not even close. As I’ve been saying, Kim Davis may well be a brave woman, but it is dangerous to the cause of religious liberty to embrace her as a symbol.

I’ve gone from being anxious about this to angry, because of what Mike Huckabee did yesterday. Here’s a clip from the conclusion of his Free Kim Davis rally, and her stage-managed release from jail:

She comes out of jail with that cheesy 1980s song “Eye of the Tiger” playing, and mounts the stage, holding hands with Huck, and giving God the glory. Now, religious liberty — our most precious freedom — is associated in the mind of the public with ersatz culture-war pageantry orchestrated by a cynical Republican presidential candidate.

I thought Ted Cruz’s turning up at the Middle Eastern bishops meeting and bashing them was the most cynical move I had ever seen by a Christian Right politician, but Huckabee may have bested that. The Family Research Council and other Christian, Inc. lobbyists are already writing the fundraising appeals, you can bet. And you can also bet that they’re bending the ear of clueless House Republicans to get them to propose provocative religious liberty legislation that stands no chance of passing, but every chance of discrediting the cause in the public’s eye. (In fact, I was told last night by someone deeply involved in this issue at the Congressional level that this is exactly what is happening.)

So I’m angry about this. Huckabee and Cruz, but especially Huckabee, are doing wonders to inject juice into their own presidential campaigns, but the political cost to the long-term good of orthodox Christians will be severe. But hey, we’ve Made A Statement, and demonstrating our emotions (and, while we’re at it, raising some money for GOP candidates and Christian advocacy groups) is the most important thing.

For conservative Christians who don’t understand why we should care about the political effect of the Kim Davis debacle, and the optics of yesterday’s release rally, I want you to consider how it would appear to you if Hillary Clinton staged a rally against police brutality around the release from jail of a West Baltimore thug who had been roughed up by the cops as they were arresting him for shooting up a neighborhood. The gangster takes the stage to the sound of gangsta rap, wearing pants hanging off his butt, with cornrowed hair and covered in tattoos.

It could well be that Hillary’s principles were in order, and an important principle was at stake. But think of how the imagery of celebrating this guy like that would make you feel. How sympathetic would you be to the worthy cause of fighting police brutality after that display? If fighting police brutality means having to stand with a victim like that, would most people be more inclined to join the cause?

Look, I’m not comparing Kim Davis to a gangbanger. What I’m telling you is how this situation, especially yesterday’s celebration, looks to a whole lot of people outside our bubble. And it matters. It matters to all of us. Our side has no leadership, only opportunists leading the mob.

UPDATE: I could hardly ask for a more perfect vindication of my point about political symbolism than the Twitter storm by liberals who are ALL OFFENDED by my use of the stereotypical inner-city black man as a negative symbol in my example for right-wing readers. The point of bringing that up was to make Christian conservatives see that Kim Davis, who looks like an ordinary rural Christian woman who violated a law to them, is a hugely loaded negative symbol for people outside their cultural bubble. Similarly, the black man I described in that context — a man who looks like an ordinary inner-city black man, though a lawbreaker — appears to a lot of people on the Right as a hugely loaded negative symbol. Whether it is fair or not doesn’t matter. Young inner-city black men are widely perceived on the Right as menacing. Rural religious white people are widely perceived on the Left as threatening, though in a different way. Symbolism matters.

If you’re one of the progressives freaking out over my illustration, chances are you don’t spend any time thinking about how what looks normal to you looks to people outside your bubble. The people outside your bubble might well be prejudiced against inner-city black men, or rural white Christians, but their prejudice does not obviate the political reality of the symbolism.

As Reagan’s imagemaker Michael Deaver understood, people in this culture pay attention to the image, not the verbal content. Put Reagan in front of a wall of flags, that’s what people will remember, not what they said. In Kim Davis’s case, many people not inside the conservative/conservative Christian bubble see that rally, and see nothing more than leading Republican politicians expressing solidarity with a bunch of countrified religious bigots who would break the law to stand in the way of gay rights. In the hypothetical gangbanger example I brought up, many people outside the progressive bubble would see that rally, and see nothing more than a leading Democratic politician expressing solidarity with a street thug who exemplified their fears.

Fairness has nothing to do with it.

September 8, 2015

What Sentimental Humanitarianism Won’t See

In one of the comments on the blog just now, a reader wrote:

There is no reason why a few hundred thousand refugees a year should be a threat to a Europe of 500 million people. If a culture is so fragile that it cannot deal with a desperate and downtrodden minority looking for a job and a home, then surely they need to change.

Looking for a job, in Europe? Let’s see what the current unemployment rates are in selected countries there:

Spain: 22.7%

France: 10.5%

Italy: 12.4%

Germany: 4.7%

UK: 5.4%

Hungary: 7.3%

Czech Republic: 5.9%

Poland: 7.9%

Slovakia: 12.1%

Netherlands: 7.0%

Belgium: 8.5%

Portugal: 13.0%

Greece: 25.6%

By contrast, in the United States, at the height of the Great Recession (late winter-spring 2010), the unemployment rate was 9.9%.

Obviously the economies of some EU countries — Germany, the UK, the Netherlands — are more able to absorb newcomers. The thing is, what jobs are available in those countries ought to be first offered to EU citizens from countries suffering the worst from unemployment.

How do you convince the people of France and Italy, for example, who are already highly taxed, and whose economies are sluggish, that they should add hundreds of thousands of foreigners to the welfare rolls? France, for example, cannot provide jobs or socialization for Arab migrants and their children, who live in Parisian suburbs:

When the director of a job centre organised a visit to the Louvre for unemployed youngsters, she knew it would be a rare event. Sevran is one of France’s poorest places, north-east of the Paris périphérique. The jobless rate is 18%, and over 40% among the young. Yet the director was taken aback by how exceptional the visit proved. Of the 40 locals who made the 32km (20-mile) trip, 15 had never left Sevran, and 35 had never seen a museum.

Sevran is one of France’s 717 “sensitive urban zones”, most of them in the banlieues. In such places unemployment is over twice the national rate. More than half the residents are of foreign origin, chiefly Algerian, Moroccan and sub-Saharan African. Three-quarters live in subsidised housing; 36% are below the poverty line, three times the national average.

Where are the 24,000 refugees France is taking in over the next two years going to live? What kind of work are they going to do? Spain has unofficially agreed to take in 18,000. In a country of nearly 23 percent unemployment, is there any hope that these migrants will get jobs?

Does anyone think these people will ever leave?

Germany is prepared to accept 500,000 migrants per year for the next several years, says Chancellor Merkel’s deputy. That’s breathtaking. I’m curious to know, however, what happens if Germany grants all, or even most, of these migrants asylum. Once they’re within the EU, they have freedom of movement, right? What is to stop them from migrating elsewhere within the EU to live and to work? Maybe there’s something I don’t understand about how the EU works — please correct me if you do — but it seems to me that once these migrants are given a firm foothold in Germany, they will be able to move around. And certainly any children they have who are born on German soil will have freedom of movement to live and to work elsewhere in the EU. Right?

Look, none of this is to say that these countries shouldn’t accept these migrants for humanitarian reasons. That is up to them to decide. The point is simply that many European countries are hard pressed economically to provide enough jobs for their own citizens, and a hugely disproportionate number of Arab Muslim and African immigrants living within those countries are unemployed and unemployable. The challenge is not simply one that can be adequately met with vague humanitarianism. The easy moralizing of people — especially Americans — like the commenter I quoted at the start of this post really is foolish. And it’s dangerous, because it fails to take into account the economic and social fragility of Europe.

Here is a new 30-minute documentary recently broadcast on the German network ZDF. It asks hard questions about the integration of Muslims into German society. The reporter goes to schools and learns that German-born, German-raised young Muslims openly reject the values of Germany. They believe that women must obey men unquestioningly. They believe Jews are pigs, and that the Christian cross drains them of their Islamic power. They sympathize with honor killings. And, according to the documentary, when these kids’ teachers take up these issues with their parents, the Muslim parents berate the teachers as Nazis.

The documentary is truly chilling. People on it speak of a parallel society that many Muslims in Germany set up for themselves. They feel no obligation to live by German law, or adopt German customs. The filmmaker interviews an Arab Christian refugee who says he and those like him are bullied by hardline Muslims in Germany. The filmmaker also interviews a German police officer of Turkish descent who talks frankly about how difficult it is to police Muslim immigrant communities, because they are so insular, and so determined to stick to the old ways.

Watch this, and understand that the idea that mean-spiritedness is the only reason not to open the door to refugees from the Middle East is dangerously naive. The Turkish-German cop tells the reporter that the conflicts in Germany among the refugees are not just religious, but nationalist: Syrians fight with Iraqis, Turks clash with Kurds, etc. “They live out their regional conflicts right here in our country,” he says.

These risks are what Germany and other European nations are importing now. Watch:

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 502 followers