Peggy Orenstein's Blog

March 9, 2016

Why I Wasn’t Excited About the “First Black Disney Princess”

Back in 2009, a lot of people asked me what I thought about Princess and the Frog, the film Disney said trumpeted as featuring its first African American princess. My gut reaction was, I’ll get excited when they release the film with their third black Disney princess. I mean, leaving aside for a moment whether it’s progress to make the princess industrial complex an equal opportunity exploiter, what I find, whether it’s women in general or women of color in particular, is that Hollywood (and Disney especially) makes a Big Deal when they finally, after oodles and oodles of movies

Score 1 for Freedom of Speech; Score 0 for Breast Cancer

Today I got a press release from one of my least favorite breast cancer organizations: Keep-A-Breast, the folks that brought you those annoying I ♥ Boobies bracelets. I’ve written about this before. There are so many things wrong with Keep-A-Breast it’s hard to know where to begin. There is, of course, the whole issue of the blithe sexualization of breast cancer, a disease that, trust me, is anything but sexy (hey, Baby, want to see my mastectomy? I didn’t get to “keep a breast,” dang it). I wrote back in 2010 about how the fetishizing of breasts comes at the expense of the bodies, hearts and minds attached to them.

What disturbs me more, though, is the way that focusing on a youth demographic–especially early detection in a youth demographic–is doing a disservice to the cause of breast cancer. Campaigns like this (as I said in last year’s piece, “Our Feel-Good War Against Breast Cancer”) are usually motivated by caring and grief: the woman who began Keep-A-Breast lost a friend to breast cancer in her 20s. But focusing on early detection–that is not going to reduce young women’s death rates from the disease. Keep-A-Breast urges girls to perform monthly self-exams as soon as they begin menstruating. Though comparatively small, these charities raise millions of dollars a year — Keep A Breast alone raised $3.6 million in 2011. Such campaigns are often inspired by the same heartfelt impulse that motivated Nancy Brinker to start Komen: the belief that early detection could have saved a loved one, the desire to make meaning of a tragedy.

Yet there’s no reason for anyone — let alone young girls — to perform monthly self-exams. Many breast-cancer organizations stopped pushing it more than a decade ago, when a 12-year randomized study involving more than 266,000 Chinese women, published in The Journal of the National Cancer Institute, found no difference in the number of cancers discovered, the stage of disease or mortality rates between women who were given intensive instruction in monthly self-exams and women who were not, though the former group was subject to more biopsies. The upside was that women were pretty good at finding their own cancers either way.

Beyond misinformation and squandered millions, I wondered about the wisdom of educating girls to be aware of their breasts as precancerous organs. If decades of pink-ribboned early-detection campaigns have distorted the fears of middle-aged women, exaggerated their sense of personal risk, encouraged extreme responses to even low-level diagnoses, all without significantly changing outcomes, what will it mean to direct that message to a school-aged crowd?

Young women do get breast cancer — I was one of them. Even so, breast cancer among the young, especially the very young, is rare. The median age of diagnosis in this country is 61. The median age of death is 68. The chances of a 20-year-old woman getting breast cancer in the next 10 years is about .06 percent, roughly the same as for a man in his 70s. And no one is telling him to “check your boobies.”

“It’s tricky,” said Susan Love, a breast surgeon and president of the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation. “Some young women get breast cancer, and you don’t want them to ignore it, but educating kids earlier — that bothers me. Here you are, especially in high school or junior high, just getting to know to your body. To do this search-and-destroy mission where your job is to find cancer that’s lurking even though the chance is minuscule to none. . . . It doesn’t serve anyone. And I don’t think it empowers girls. It scares them.”

Did you hear the big news? Earlier this week the Supreme Court declined Easton Area School District’s appeal to ban Keep A Breast i love boobies! bracelets in their schools. Below is an excerpt of a response blog I wrote on how I felt. Although this is a huge victory for freedom of speech for students everywhere and Keep A Breast we know our fight isn’t over. We still need your support to keep educating young people on the importance of breast cancer prevention. I hope you will consider making a donation right now. Will you support Keep A Breast?

XOXO

September 5, 2014

August 1, 2014

More on Mastectomy, Accurate Information and Treatment Choices

I’ve been camping since last Saturday, so wasn’t here when my story on contralateral mastectomy was published in the New York Times. In its aftermath, I’ve gotten positive feedback from researchers, physicians and advocates, including Karuna Jagger of Breast Cancer Action, who wrote this follow-up; Gayle Sulik, author of Pink Ribbon Blues and founder of the Breast Cancer Consortium; and Susan Love, author of Susan Love’s Breast Book (bible for the newly diagnosed) and medical director of Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation. The blogger who goes by The Risky Body also wrote two really thoughtful responses aimed at–though not exclusively for–the community of women with a known BRCA mutation.

I’ve received email from individual women in the throes of making their initial treatment decisions; from women who chose CPM and later were diagnosed with metastatic disease; and from those for whom the decision to remove the healthy breast went horribly, painfully awry (reminding me that we tend to underplay the risks and potential complications of surgery.

I’ve also read online the articles in response to the piece by those who chose CPM and are happy with that decision or who want to explain their point of view. Like this one on Slate, and this one on Forbes. So for them, in particular, there are some things that I’d like to clarify. First of all, I want to reiterate that the data on survival does not apply to those who carry a genetic predisposition to breast cancer (such as a BRCA mutation) or those with a strong family history of the disease. It applies to women who were at average risk of contracting breast cancer and are at average risk of contracting a second cancer. The vast majority of women choosing CPM fall into this category, by the way.

There were so many things I couldn’t fit into a 1200 word article–had I been able to write something longer I could’ve been far more comprehensive and nuanced. That said, I made the points that were most important to me to make. Two interesting facts I couldn’t fit in: one, this trend towards CPM has happened even as treatment reduces the likelihood of contracting a second cancer. I find that interesting. Also, this is an American phenomenon: according to Todd Tuttle, chief of surgical oncology at the University of Minnesota (Ski-U-Mah!) there was not a similar uptick of CPM in Europe over the time period studied. It’s worth noting that there is also no greater incidence of contralateral cancer or death from the disease there over that time period. Nor do European women seem to choose CPM for cosmetic or other reasons cited by American women.

Why the difference? One reason, according to researchers, is the rise in use of MRIs, which have an inordinate rate of false positives, subjecting women to the physical and psychological stress of unnecessary biopsies. According to researchers at Sloan-Kettering:

Women who had a breast MRI as part of their preoperative evaluation were three times more likely to choose CPM,” she says. MRIs may detect additional areas of breast cancer that are missed by mammography, but the rate of false positives is quite high. “If the MRI finds something that looks suspicious, many women say, ‘I would rather just have a double mastectomy than go through the process of having biopsies on my other breast.’

Another reason, is that choices are not made in a vacuum. They are made in a cultural, political and economic context. As I wrote in my New York Times Magazine piece last year (and Karuna Jaggar wrote this week, in the piece linked above), pink ribbon culture has inadvertently stoked a fear of breast cancer so that women consistently over-estimate their risk of disease. In the end, I believe, that over-estimation comes at the expense of effective advocacy.

My goal with the CPM piece, as with all my pieces on breast cancer, was to report solid information that has not been adequately reported in mainstream media, information that can reduce harm—such as over-screening and over-diagnosis—and tremind people of what is important about breast cancer advocacy: reducing the number of women who are harmed by and especially who die of breast cancer. To my mind that means focusing on potential environmental factors involved in the disease; focusing on prevention; focusing on less toxic and more effective treatment; understanding DCIS and, in particular, understanding the mechanisms of metastatic disease. One concern I had about the rise of CPM–and the statistics showing the rise was due to over-estimation of its benefits and over-estimation of the risk of a second cancer– was that by giving women a false sense of security, misleading them into thinking they were improving their odds at survival, it would detract attention and resources from where they need to go. I can’t imagine that anyone, including those who chose CPM for some other reason, would think that was a good idea. I can’t believe anyone, including those who chose CPM for other reasons, would want women to choose it because they are misunderstanding risk and benefit. I can’t imagine anyone including those who chose CPM for other reasons, would want women choosing CPM because they think it will save their lives when multiple studies–and this new one in particular–have shown that it won’t.

The research on CPM is clear, in multiple studies, that many women pursue it both because they over-estimate their risk of a second primary and because they believe CPM will be life-saving (I’ll put some links at the end of this post). Again, I would think that regardless of why you personally chose CPM you would believe it is important that newly diagnosed women make their decisions based on accurate information. In Todd Tuttle’s research, cited in my New York Times Magazine story, women estimated their chances of contralateral cancer to be 30% over 10 years when it was actually less than 5%. Maybe the women who have written in response to my piece that they chose CPM for other reasons already knew that, but obviously many women do not. Do you really want them making decisions about surgery based on such misinformation? That scares me. And it’s wrong from a public health perspective.

From that perspective women should understand, loud and clear, that CPM is not, for a woman at average risk of cancer, a medical necessity. As Steven Katz said to me during our interview, conversations with the newly diagnosed should start with, “CPM is a futile procedure in terms of prolonging life.” Then– again from a public health perspective–we can have a discussion about whether surgery should be the frontline treatment for those with intense fear or anxiety about cancer even when that surgery has no medical basis.

A number of women have written to me and said they had CPM for cosmetic reasons. That’s a choice, certainly, as any cosmetic procedure is a choice. In making it, you certainly have to balance the risks of surgery with other factors. Personally, I’d like newly diagnosed women to know that I don’t feel at all “unbalanced” with one fake breast and one real breast. My breasts are not asymmetrical, or no more asymmetrical than the average woman’s or than they were before after 50+ years of wear and tear. With my clothes on—including scoop necks and low-cut bathing suits–you can’t tell at all. Naked, my breasts look about as good as they did before, though the reconstructed breast has more scars both from where the tumors were removed and because in the last four months I’ve had two biopsies on that side (both turned out to be–guess what?–not one but TWO rare surgical complications….). Also, again in the spirit of full disclosure, my previous radiation compromised the nipple-sparing surgery, so while I have a nipple it doesn’t look as good as it might or like the one on the other side. CPM wouldn’t have changed that. But if those things weren’t true, you’d have a hard time visually distinguishing the fake from the real. Internally (i.e., to me) they do feel different. My natural breast feel natural. My fake one feels like I’m wearing a tight bra all the time that I can’t take off. Women who are considering implants (I have a DIEP-flap because my previous radiation makes implants difficult) can certainly wait to have a second breast removed and reconstructed to see how they feel about it, even though it does mean further surgery. But, really, there’s no rush. DIEP has to be done all at once, which complicates the issue. Ultimately, I would advise a woman considering her choices who is concerned about symmetry to talk to those who have had DIEP on one side and on both sides and ask, if possible, to see their breasts. I’m happy to show mine (but only in person—not on the web!!) . You really have to see reconstruction in person to totally get it.

As for those who have decided to go flat, that too is an option and always has been. I definitely considered it. As long as it’s understood that it’s not life-prolonging for those at average risk or that what you’re doing is somehow implicitly superior (in terms of treatment or in terms of maternal sacrifice) to those who, say, have a lumpectomy and radiation.

Anyway. I’m not here to litigate anyone’s past choices, including my own. My belief is that you make the treatment decisions that you make with the information you have at the time of diagnosis understanding that such information may change, become obsolete or incorrect. And you don’t look back. When I was originally diagnosed chemo was not recommended. A few years later, all women under 40 with cancer were treated with chemo as a matter of course. Oops. A few years after that, they went back to the way it was when I was first diagnosed. Oops again. I was among the first women to have a modified sentinel node biopsy. A few months earlier, they would’ve done the big scoop. A few months later, I would have had an actual sentinel node biopsy. So it goes. I’ve been around this world a long, long time. Longer than most patients, I’d wager. I’ve seen a lot.

I think about the women who had the Halsted radical mastectomy (which, according to Robert Aronowitz, even he knew would only prevent local recurrence, not metastatic disease); I wonder how they felt when it first became clear that lumpectomy and radiation would have sufficed. Were they resistant? Angry? Sorry? Did they celebrate that other women, that their own daughters, would not have to go through what they did?

Because that is the great news, isn’t it? Women at average risk do not have to fear keeping their healthy breast when diagnosed with cancer. I’m so grateful for that for the sake of anyone diagnosed in the future. And again: shouldn’t we be making sure that newly diagnosed women know that so that they make their decisions from a perspective of the greatest knowledge?

Finally, as promised, here are some links beyond those listed above. I would encourage anyone interested in this issue, whether or not you have chosen CPM, to actually look at the research.

Increasing rates of CPM among women with DCIS

CPM among women with sporadic breast cancer

Increasing use of CPM among Breast Cancer Patients: A Trend Towards More Aggressive Treatment

Preventative Mastectomy Does Little to Increase Life Expectency (CBS News)

I imagine that now I will get a lot of comments from women explaining why they personally had CPM. That’s fine, I guess. But not the point. The point is to ensure women have a realistic understanding of what the procedure can and cannot do for them. It is tragic and even cruel for someone to have CPM based on the false belief that it will prevent death. I hope we can all agree on that.

May 9, 2014

Alone in a Room on National TV

So you know when you’re watching CNN or MSNBC or FOX news orPBS or whatever and they have some talking head on a monitor chatting with the host? Well here’s how they do that when you’re the guest: you are sitting alone in a black-walled, darkened room staring into a camera lens. You do not see the host. You do not see the other guests. You do not see yourself. You have no idea whether or not you are on-screen at any given moment. You hear the host and the other guests through the earpiece and you talk earnestly at nothing at all. It’s a seriously weird deal. But that’s how it goes, especially if you live in California and most of the media is in New York. I never get used to it. But I did it the other night because I was asked to be on the PBS News Hour with Gwen Eiffel and, really, how cool is that?

Anyway, here’s how it came out:

March 9, 2014

My Daughter’s Grrrilla Tactics: #Unapologetic

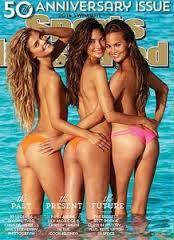

The Barbie Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue cover got all the buzz, but it was nowhere to be found yesterday at our local book store. Instead, this cover caught my 10-year-old’s eye:

“Ick!” My daughter said. “What does that have to do with sports, Mom?”

“Absolutely nothing,” I responded.

She glanced at the next magazine over, also Sports Illustrated, with this cover of Mikaela Shiffrin looking very real and really happy with her incredible accomplishments.

My daughter looked back and forth for a moment, then grabbed the Shiffrin cover and put it on top of the swimsuit issue, blocking it from view.

“There,” she said, satisfied, and walked away.

Yes. That’s my grrrl.

March 7, 2014

What Do Little Girls Really Learn from “Career” Barbies?

Like a lot of moms, I faced the Barbie dilemma when my daughter was younger. I solved it–ta da!–through hypocrisy and mixed messages. Ok, maybe that’s a little harsh. But I figured a little bit of Barbie would sate her appetite (and stop the nagging) without doing too much harm. Like a vaccination, or homeopathic innoculation against the Big Bad. I told myself my daughter didn’t use her dolls for fashion play anyway: her Barbie “funeral,” for instance, was a tour de force of childhood imagination. I told myself I only got her “good” Barbies: ethnic Barbies, Wonder Woman Barbie, Cleopatra Barbie. Now that she’s 10 and long ago gave the dolls away (or “mummified” them and buried them in the back yard in a “time capsule”), I can’t say whether they’ll have any latent impact on her body image or self-perception. It would seem ludicrous, at any rate, to try to pinpoint the impact of one toy. To me it was never about a single product anyway–not even the Princesses, though I’m often accused of thinking that–it was about the accrual of products, the conveyor belt we put girls on at ever-younger ages that tells them that how they look, first and foremost, is who they are.

But now, according to a study published this week, it turns out that playing with Barbie, even career Barbie, may indeed limit girls’ perception of their own future choices. Psychologists at Oregon State and the University of Santa Cruz randomly assigned girls ages 4-7 to play with one of three dolls. Two were Barbies: a fashion Barbie (in a dress and high heels);

and a “career” Barbie with a doctor’s coat and stethoscope.

The third, “control” doll was a Mrs. Potato Head, who, although she comes with fashion accessories such as a purse and shoes, doesn’t have Barbie’s sexualized (and totally unrealistic) curves.

(NOTE: I just pulled these images from the web: I don’t know which Barbies or Potato Heads they used. Interestingly, though, the doctor Barbie I found on Amazon costs $35 whereas the fashionista Barbies are $11-$15. And one more note: I’m from the era when we used actual POTATOES for our Potato Head dolls, sticking them with push-pin pieces on which you could easily impale yourself–or your sibling. Those were the days, eh? Anyway, back to the topic at hand…).

Ahem. So, after just a few minutes of play, the girls were asked if they could do any of 10 occupations when they grew up. They were also asked if boys could do those jobs. Half of the careers, according to the authors, were male-dominated and half were female dominated. The results:

Girls who played with Barbie thought they could do fewer jobs than boys could do. But girls who played with Mrs. Potato Head reported nearly the same number of possible careers for themselves and for boys.

More to the point:

There was no difference in results between girls who played with a Barbie wearing a dress and the career-focused, doctor version of the doll.

Obviously, the study is not definitive. Obviously, one doll isn’t going to make the critical difference in a young woman’s life blah blah blah. Still, it’s interesting that it doesn’t matter whether the girls played with fashion Barbie or doctor Barbie, the doll had the same effect and in only a few minutes. That reminded me of a study I wrote about in CAMD in which college women enrolled in an advanced calculus class were asked to watch a series of four, 30-second TV commercials. The first group watched four netural ads. The second group watched two neutral ads and two depicting stereotypes about women (a girl enraptured by acne medicine; a woman drooling over a brownie mix). Afterward they completed a survey and—bing!—the group who’d seen the stereo- typed ads expressed less interest in math- and science-related careers than classmates who had watched only the neutral ones. Let me repeat: the effect was demonstrable after watching two ads. And guess who performed better on a math test, coeds who took it after being asked to try on a bathing suit or those who had been asked to try on a sweater? (Hint: the latter group; interestingly, male students showed no such disparity.)

Now think about the culture girls are exposed to over and over and over and over and over, whether in toys or movies or tv or music videos, in which regardless of what else you are—smart, athletic, kind, even feminist, even old—you must be “hot.” Perhaps, then, the issue is not “well, one doll can’t have that much of an impact,” so much as “if playing with one doll for a few minutes has that much impact what is the effect of the tsunami of sexualization that girls confront every day, year after year?”

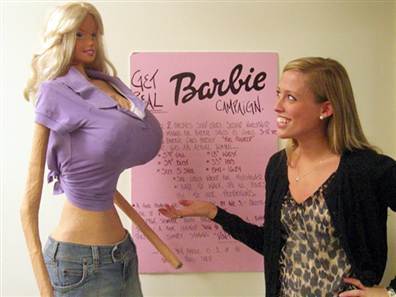

(If Barbie were life-sized she’d be 6 feet tall with a 39″ bust, 18″ waist, and 33″ hips. This representation was made by then-high school student Galia Slayen and originally from a post by Today News)

January 23, 2014

Parenting in the Digital Age

I was just re-reading Catherine Steiner-Adair’s book, The Big Disconnect, and came across this passage:

Children come to life innocent, unaware of the harsh aspects of pain and suffering and how cruel people can be. Part of the job of parenting is to protect them from that harsh truth long enough for them to develop a sense of goodness and core values of optimism, trust, internal curiosity, and a hunger for learning. If they see too much too soon–before they’re neurologically and emotionally ready to process it–it can short-circuit that natural curiosity. Boys and girls alike are easily traumatized by premature exposure to the media-based adult culture that cultivates cynicism and cynical values, treats sex and violence as entertainment, routinely sexualizes perceptions of girls and women, and encourages aggression in boys.

As a parent, I was initially taken aback by how actively I’ve needed to protect my child’s childhood (and her creative imagination) from predatory marketers and crass media. I had no idea that would be such a challenge. If you haven’t seen Steiner-Adair’s book check it out. It has great thoughts on how to guide your kids through the digital wilderness (and, I’m warning you now, won’t let you off the hook about your own habits). If her name sounds familiar, it’s because she’s also authored a path-breaking curriculum on fostering health and leadership among girls.

January 18, 2014

140 Characters Isn’t Enough to Say I’m Sorry

So I am in the Twittersphere dog house and, it seems, justifiably so. It’s hard to respond in 140 chars (especially hundreds of times) so whether I dig myself in further here or adequately respond, at least I have a little space.

Here goes.

I was wrong, stupid and insensitive to not read Lisa Bonchek Adams herself before promoting Bill Keller’s editorial. The internet is often a reactive place, and although I try to resist that impulse, to think before I tweet, I messed up. I hit the send button without doing the research I should have based on something in his piece that did resonate quite strongly with me —the idea that the American medical establishment prioritizes quantity over quality of life in end-of-life care. I didn’t much think about the personal example being used to make that point, just assumed he was right (and you know what happens when you assume….).

Here was my thinking:

I am hyper-sensitive to the idea that cancer patients who don’t “do everything” are lesser than others. I have a dear friend who opted to stop treatment for metastatic disease. She faced pressure by her doctors. She faced pressure by her family (and yes, she had small children –she was in her 30s). People accused her of “giving up.” She was not seen as brave or heroic or self-determining. Years later I bumped into a mutual friend who still referred to this woman as someone who “gave up the fight.” That rankled. So when I read a journalist saying we needed to think about our attitude regarding end-of-life care and “heroic measures,” it landed deeply with me.

Even not end-of-life care. I am supposed to be in treatment for my own disease for four more years. Or maybe 9 more years, if my doctors have their way. I will have to make a decision about that at some point. It makes my stomach sink to think about nine more years of crappy side effects. But when do you say when? How do I weigh survival benefit versus lifestyle benefit? I struggle mightily with this. I suspect that if I choose to say no to the treatment it will be a stigmatizing choice, explicable only to a few of those close to me. If I were later to be diagnosed with metastatic disease, would I be blamed? Would I blame myself?

Meanwhile, I am still feeling the sting of what Gayle Sulik called “heartfelt misinformation” spread by Amy Robach in the wake of her cancer diagnosis. I wish her well, of course I do. I mean obviously. Unfortunately—and I know this from personal experience, too–when you put yourself in the public eye as a cancer patient you no longer get a free pass. Gayle Sulik wrote beautifully about this: So I was, I guess, feeling easily triggered by anyone’s personal story that smacked of that.

Yet Lisa Adams’ does not. And none of the above is an excuse for not doing my own research to find out. she was not a good choice for a discussion of end-of-life care. I apologize to her for thoughtlessly piling on. Again, I refer to Gayle Sulik, who wrote her own piece about the Keller-Adams controversy that says it all.

Some have accused me of backing “team NY Times” in this debate because of my relationship there. Let me give you a little inside baseball: while we have the amazing gift of prominence and audience for our work, we Magazine writers do not have much by way of internal status. We operate in a netherworld, our inclusion on “the team” situational, depending on whether we reflect well or poorly on the corporation. Nor do I know Bill Keller personally, at least I don’t recall ever meeting him (so please don’t tell me that I did in 1988 and just forgot). I do, however, know his wife, Emma Gilbey Keller. We have met in person once, for about 30 seconds, but we are Twitter pals. After my recurrence, she emailed me to tell me she’d been through the surgery I was facing—the DIEP-flap reconstruction—and offered herself as a resource. I knew no one who had gone through this so that was a Godsend. Emma was unstintingly generous with her time, sending me long emails, checking in on me when she didn’t hear from me, letting me know what to expect, guiding me through a deeply frightening and painful (physically and emotionally) process, boosting my morale and offering information. She even sent me a good luck blanket to take into the hospital, because she had so often been cold during the week in intensive care. All, as it turned out, while her father, with whom she was extremely close, was dying and she was recovering from her own cancer surgery. Again, we are essentially strangers–I blurbed a book of hers that I liked years ago, but we don’ t know each other. I am so grateful to her and always will be. So if anything colored my willingness to back Bill without question, it was my gratitude and loyalty to Emma. That means I will not add to the discussion and speculation about them in this space.

Again, that is not an excuse. I was wrong not to do my due diligence. And I apologize, again, to Lisa Adams, her followers as well as my own followers and readers for that. One of the unsettling parts of the internet is that you can’t take things back. I would have done this differently. It’s a lesson learned.

August 19, 2013

Just in Case

Just in case you stop by this blog and are wondering: Hey, Peggy, where you at? I am, for the moment, trying to stay offline as I report and frame a new book. Unless I pull way back from other forms of communication, I have a super hard time doing that. So I’ll be back at some point, when I’m further along. Meanwhile, thank you for your patience and on-going interest in my work! -Peggy

Peggy Orenstein's Blog

- Peggy Orenstein's profile

- 720 followers