Sharon Bala's Blog

December 18, 2024

Riddle Fence

This Fall, I joined Riddle Fence as the Creative Non-Fiction Editor. Since then, I’ve been sifting through hundreds of submissions, searching for gold. A few people have asked what exactly I hope to publish so here are some suggestions.

First off, please don’t send me:poetry (there are other editors helming that section)

fiction (ditto!)

reviews (they are published online; get in touch with the managing editor)

opinion pieces

academic essays

journalism

Riddle Fence #53

And here’s what I want:Creative non-fiction means true stories. Story is important. There should be a narrative drive and emotional resonance. As in fiction, if you’re skirting the emotions, you’re likely skirting the conflict too. Any story — true or false — without conflict is boring.

Strong writing. That might be poetry in motion — beautiful sentences that contain insight, interesting metaphor, or simply demand to be read aloud. But strong writing can also be spare, unfussy prose.

The important thing is clarity. If the work is full of vague abstractions, if the tense shifts are perplexing, if there are too many flashbacks and flashforwards that trip the reader up, it’s an automatic rejection. Ask your most critical frenemy to read your submission and circle the places where they got confused.

Clarity also applies to the subject as a whole. Too many questions in an essay is a red flag, suggesting the author is still feeling their way through a draft. You should be able to summarize your piece in a single sentence. (In the cover letter, not the essay!) For example, Andreae Callanan’s “All The Ghosts a Voice Can Summon” is about complicated grief and Sinéad O’Connor. Bushra Junaid’s “On Hosting” is about feeling like an outsider in one’s own home. Though I can’t take credit for finding either of these, they are excellent examples of the types of submissions I want to publish.

When I tell you an essay is about complicated grief or feeling like an outsider, you can already feel the tension. Find a subject that is difficult and personally hurts you and then wrestle it out on the page.

Brevity. I have 6,500 words per issue and a mandate to publish at least 50% NL-content. Anything that’s over 2,500 words and doesn’t fit into that mandate must hit all five marks above. If your piece is 750 words, you can get away with 4/5, maybe even 3/5. But if your essay is over 3,000 words and you are not from this province, writing in this province or about this province, then it absolutely must be a stellar 5/5 and even then, I might still have to reject on the grounds of word-count. What is this submission about? What makes you uncomfortable? Hone in on those two things and strip away the excess. Here are some tips on trimming.

Speaking of identity…Riddle Fence is a Newfoundland and Labrador arts and letters magazine. This is a place of storytellers and vibrant culture and part of our mandate is to foster those things, which is why I’m aiming for 50% NL-content in the creative non-fiction section.

In practice that means I’m looking at addresses. Please self-identity if you were born here and are in the diaspora. I’m interested in writing about this place as well. If you lived here and are writing a reflection on that time, I’m game to read it. I’m less keen on tourism. I’m starved for writing from Labrador or by Labrador authors. Please, please, self-identify in the cover letter.

None of this equals automatic acceptance. The writing still has to hit at least 5 or 6 of the marks listed above but the odds of publication are better.

This is not a Riddle Fence mandate but a personal goal: I want more colour in our pages. Are you a BIPOC author? Self-identify. (I know, I know. I hate doing it too but we get hundreds and hundreds of submissions. Help an editor out!)

The ideal submissionI’d love to see something unconventional, say a collection of vignettes curated around a theme. See, for example, Gary Barwin’s “Meat and Bone” in this issue of Grain Magazine. Or a complex essay that combines a first person narrative with a didactic deep-dive into a related subject, toggling back and forth, each strand of the essay shining a light on its opposite. For the latter, I would break the 3,000 word limit, especially if it checked the NL-content box. Good examples of this kind of complex creative non-fiction can be found in Alicia Elliott’s A Mind Spread Out On The Ground, Jen Sookfong Lee’s Superfan, and Sarah Polley’s Run Towards The Danger.

And don’t forget!My new year’s resolution is that I’m not reading any submission that doesn’t conform to the guidelines. So please attend to these basic civilities:

Upload your work as a .doc or .docx file

Double-space

Make sure your name, title, and word count appear on every page of your submission

Cover letters are appreciated, especially if they include the word count

Okay, done all that? You’re ready to submit. I can’t wait to read it!

November 13, 2024

True beginnings

This is the fourth and final installment in a series on beginnings. It’s best to read these in order, starting with the first post. Today’s is all about non-fiction.

In general, the guidelines of fiction apply to non-fiction as well. Aim for context and curiosity. Write with clarity and sharp specifics. Take care with grammar, diction, and syntax. Don’t bore or confuse the reader. Ofcourse, it’s much, much easier to write plodding non-fiction so you have to work harder to find a compelling opening.

Begin with an anecdote, rather than a list of factual statements. Ideally something with high stakes drama as in Patricia B. McConnell’s The Other End of the Leash (more on that below) or biting humour as in Cat Bohannon’s Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution, which is a popular science book based on her dissertation.

An anecdotal opening, especially one that paints a clear scene, is especially important in non-fiction that is heavily informational and research-based. But sometimes memoirists need this reminder too. Show the reader that you can tell an engaging story and they will remain invested during the long passages of exposition.

A singular voice comes in handy. Non-fiction is so heavy on the telling that what a storyteller sounds like can make a big difference. See for example, Michael Harris’ dry wit in the opening paragraphs of Rare Ambition: The Crosbies of Newfoundland.

Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, an insightful and meticulously researched tome about racism and caste hierarchy in America, begins with an old pathogen and a medical mystery in Siberia. Beginning with the unexpected is a brilliant move. While the reader is fully invested in the mysterious illness, they are also wondering what it has to do with racism. Curiouser and curiouser….

Another device, often used in non-fiction, is subversion. See, for example, Clarisse Loughrey’s very funny review of Bullet Train which likens the movie to a try-hard child cartwheeling into a wall.

When authors begin strong, with a story, scene, or anecdote, it’s instructive to look at the passage that follows. The Other End of the Leash, a book about dog psychology, opens with a true story. Driving home one night, the author sees two dogs blithely trotting down the highway, oblivious to traffic. Human peril is elementary. If you really want to make a reader anxious, put an animal in harm’s way. Having set the stakes, described the scene, and introduced the canine characters, McConnell describes pulling over and, with infinite care and excruciating patience, using body language to coax the dogs to safety. WHEW.

The passage that follows gets into the nitty gritty of dog cognition and the twinned history of canines and humans etc. etc. It’s fascinating but more so in the context of the scene we’ve just witnessed. In effect, McConnell has shown and then told. Through the book, she employs this strategy of using specific anecdotes and examples to illustrate the facts she describes.

Compare the opening sentences of the first and second passage:

“It was twilight so it was hard to tell exactly what the two dark lumps on the road were.”

vs.

“All dogs are brilliant at perceiving the slightest movement that we make and they assume that each tiny motion has meaning.”

Notice in the twilight opening how she provides some context (time: twilight and place: road) and leaves you with a question (what are those lumps?). And at the end of the brilliant opening scene — after we watch her save the dogs — the reader is left wondering how the hell she did that and how they can learn those skills too. That’s the curiosity that animates the entire book.

So here’s the last lesson about openings (in fiction and non-fiction): It’s not enough to have a catchy one. You must maintain that strength of prose and clarity and court the reader’s inquiry right to the end. But first, start as you mean to go on.

November 11, 2024

How to lose a reader

This is the third in a series on Openers. In the first post, I harped on about the importance of clarity. The opposite is confusion. If you confuse your reader at the jump, they are likely to close the book, turn off the e-reader, or reject the manuscript. So let’s look at what not to do.

But first, a caveat….

Rule Free ZoneThere are no rules for good writing. Here are some old saws you’ve probably heard:

we must kill our darlings

show, don’t tell

don’t begin a story with a nightmare

These are useful guidelines but they will only serve you 75-95% of the time. Here are three more.

How to lose a reader in three moves or lessOpen with dialogueBeginning with dialogue is one of the most difficult ways to open a narrative. Remember: the reader arrives with a blank slate and if all they get is disembodied voices without context, they are liable to get confused and bored.

This is controversial, and I love much of Iris Murdoch’s work, but A Fairly Honourable Defeat has an irritating opening. Some voices (impossible to know who or how many) carry on a vague conversation about some other characters. Confusing. Boring. Next.

So that’s the guideline. But it’s not a rule. If you open with dialogue, make it compelling. Ideally, the speech hooks the reader (perhaps with a provocative question, a la EB White’s Charlotte’s Web) and then the author swiftly provides crucial context that roots the reader firmly in the scene.

Open with too many charactersImagine going to a new partner’s family reunion and being quickly introduced to a room full of strangers, who all look alike, and then being expected to keep track of their names, peculiarities, convoluted relationships, jealousies, and alliances. Hideous. Don’t put your reader in that nightmare.

If you open with a cast party, be intentional about who you introduce and when. Leave the reader enough sharp specifics to fix one character firmly in mind before introducing the next. A good example comes from the opening pages of Curtis Sittenfeld’s Prep, which takes place at a boarding school that’s busy with students and teachers.

Open with abstractionsThis might be a mistake more common to non-fiction. Any passage that is heavy on vague generalities and light on specifics is likely to be poor. But in an opening, it’s almost certainly a bore.

On the other hand, there is Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities which begins with a page of contradictory general statements. It works because it’s funny as hell. The prose and voice alone are compelling. And eventually, he does get around to the point!

The last post in the series comes out on Wednesday and it is devoted to non-fiction.

November 8, 2024

And then they woke up…

This is the second in a series on opening lines. If you haven’t read it, here’s the first post.

One of the most common things I tell my clients and authors I mentor is this: your opening is a red herring. This guideline applies to fiction and non-fiction equally.

ProloguesIt’s very likely your prologue, beautifully written though it might be, is unnecessary. Worse: it’s probably spoiling the story by telegraphing the climax or some other key drama that should be revealed gradually or giving away the ending.

If the story is about a young protagonist on a perilous adventure but the prologue reveals him in his 80s. If your happily ever happens in the prologue there should be a very good reason. Or if the story is a will they/ won’t they romance don’t begin with the wedding. Anytime your story begins in the future of the main narrative’s present, take care.

Which is not to say it can’t or shouldn’t be done. In Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude he begins with the iconic line: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Notice we are begin at a moment of extreme peril and then rewinding to (presumably learn) how this guy got here. The stakes in the future remain (along with the question: will he make it?) even as we return to the past.

Similarly, there are many prologues that serve a strong narrative purpose, offering crucial context about character or beginning on a crisis that grabs the reader’s attention.

Preludes and PrefacesAre you writing a non-fiction book with a preface or prelude? Interrogate it. Sometimes this is the correct place to begin the manuscript or book. More often, in a draft, it’s a list of musings that you as the author need to ponder. I call these “notes to self” and they can be incredibly illuminating, giving you information about the themes or ideas you want to explore in the work.

Sometimes it’s a summary of the journey you as the writer want to take the reader on. Rather than telling them in an information dump, gradually reveal the journey through the book. Nothing you write is a waste of time. Most of the work of drafting is getting things on paper and panning for gold. Sometimes those nuggets are things you keep and expand on in the narrative. Other times, it’s a document you keep close by as a checklist or outline, while you write.

Often in a non-fiction draft, preludes include a list of questions. Be wary of opening on too many questions. Remember: context and curiosity. The author provides the context that makes the reader ask questions. Often the list of questions you start with are the ones you need to answer through research and narrative exploration.

Alarm ClockIt’s natural that so many of us default to a dream/ nightmare/ alarm clock wake up sequence when starting our stories. Afterall, that’s how our days begin. (Remember that old Degrassi theme song?)

Sometimes this morning routine is a narrative limbering up rather than the true beginning, which is likely further down the page. Ask yourself where a reader’s curiosity might be peaked. Or perhaps you can search for the moment where the character’s day becomes one like no other. In other words: the inciting incident, the thing that sets the hero on their journey. Once you find this, you can kill that darling wake up scene. Simple, right? (There comes a point in revisions when — hand-on-heart — deleting is joyful because it’s the only thing that is easy.)

But it might be that key things happen in the character’s morning or those early moments reveal information that provides necessary context for the reader. Perhaps the first moments of the day set up the stakes which are crucial to the inciting incident. This is when a flashback can come in handy.

Have a look at Janika Oza’s A History of Burning. It begins with a hook and then rewinds back to reveal the first minutes of the day, setting up the stakes for the protagonist, revealing crucial background about his family and home, and then moving to the inciting incident. The trick here is that her flashback is swift (without feeling rushed). In fact, the whole passage is a masterclass in openings. It’s well worth a dissection.

On the other hand, there are some stories that must begin with a dream or nightmare or the character waking up. Cliches have been unfairly maligned. They are a useful tool that, when used judicious, can be powerful. Like direct dialogue and repetition though, they have been wielded too often without care and intention.

Months before I signed with an agent and sold the manuscript and began working with my brilliant, thoughtful editors, there was an editor at a different publishing house who told me not to open The Boat People with a nightmare. He didn’t explain why, just said don’t do it. In hindsight, I don’t think he’d read much of the manuscript, just had a knee-jerk anti-cliche reaction.

There was no other place for that novel to begin. Mahindan is trapped in one nightmare until he gets caught in the living nightmare that comes next. And by some good fortune I was stubborn about this opening, even before I had those words to articulate why it was the right one. (Also good fortune: my agent and actual editors never mentioned the opening, though they sure did make plenty of other suggestions!)

It’s important to stay in the driver’s seat when it comes to your stories. Let editors and early readers ride shotgun. Consider their suggestions. But if something feels right to you, stick with it, even if it is a cliche.

Monday’s post is all about what not to do in the opening. Don’t touch that dial.

November 7, 2024

To begin with…

A few weeks before The Boat People hit shelves, I served as a reader for the CBC’s annual short fiction contest. This meant I was reading hundreds of anonymous submissions while hunch-backed on the couch.

“Every other story begins with a character waking up from a dream,” I grumbled to my husband. To which, he replied: “Your book starts like that too.”

It was not an Oprah ah-hah moment so much as an oh shit, stop the presses moment. Once you know the cliche, you will notice it everywhere. Since then, I’ve thought a lot about openings and how to craft ones that hook and hold.

Context & CuriosityThe strongest openings give readers context that makes them curious. Context means: who (character), what (plot), when (time), where (setting), and why (stakes). As an author, you must decide what, and how much, detail to offer while leaving the reader with questions so they keep turning pages.

Curiosity can be stoked by the usual suspects: drama (meaning high stakes and struggle), tragedy, mystery, romance, lust, and love. It might also be conjured by some intriguing world-building, as in sci-fi, fantasy, and speculative fiction. Beautiful prose conjuring setting, combined with a seductive narrative voice can also do the trick. See for example the opening lines of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things or just about anything by Michael Crummey.

The strange, the unusual or idiosyncratic also make good openers. George Saunders is particularly adept at this with his slightly off-kilter fictional worlds. But an idiosyncratic narrative voice can be so disruptive of the norm that it alone hooks. Thomas King’s One Good Story, That One is an excellent example as is Ian McCurdy’s short story Crossroads.

Types of OpenersLights! Camera! Action!: this is an opening that combines an attention-grabbing first sentence that hooks the reader with a swift set up of character, setting, and stakes combined with an inciting incident that puts the plot in motion and sets the hero and the reader on their journey. The reader is immediately carried away, perhaps gulping the narrative in one sitting. Check out RF Kuang’s Yellowface as an example. Classic thrillers are very good at this too (see: The Retreat by Elisabeth de Mariaffi). So is the slower paced and lyrical, A History of Burning by Janika Oza.

Inciting Incident: A reliable place to begin is on the day when everything changes for the hero. Think about the inciting incident, ie. the thing that puts the plot in motion, and begin as close as possible to that point. Frodo Baggins is minding his own damn business in the Shire when his drunk uncle gives him the world’s most dangerous present. Cinderella is an indentured servant until an invitation arrives from the palace. Better still: Jessica Grant’s brilliant short story My Husband’s Jump.

Aphorism: This is a fun old-timey hook. Altogether now… “All happy families are alike, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” Note that in both cases, we have coherent sentences that spark curiosity. You might wonder, for example: how? and does he truly? And both Tolstoy and Austen jump right from abstract aphorism into specific domestic scenes. Anna Karenina begins with the revelation of an affair that throws a family into chaos. And in Pride & Prejudice, an eligible bachelor moves in next door to a family with five unmarried daughters. So we swiftly move from generic truism to specific drama (the day everything changed).

The subtle route: There’s a risk to a flashy beginning: hurtling headlong into cliche or artificiality. Many of the best openings are quieter, subtler, and more artful. In Téa Mutonji’s short story The Photographer’s Wife, two people meet. One is an ardent pursuer and the other is ambivalent but finally agrees to a date. The apparent power imbalance (ie. tension) and the narrator’s reluctance makes the reader wonder why and what will happen next? Just enough information to elicit questions.

In Michael Christie’s The Extra two people are so hard up financially, they rent a space without running water and must urinate into the same jugs they later use to collect drinking water. Christie’s prose is pristine, the details visceral and specific. Right away, we have a picture of characters on the edge (stakes). Naturally the reader wonders will they be okay? Or perhaps the reader stays for the quality of the writing. When done exceptionally well, prose alone can carry the narrative a long way. See: Kiran Desai’s The Inheritance of Loss.

A dream: I began this post with dreams. Yes, they are cliche. No, they are not verboten. There’s the cliff. Hang tight till Friday for Part II of this series when I tell you why.

November 4, 2024

Search Party

When I help emerging authors with their manuscripts — or revise my own wonky drafts — one of the main issues I notice is a lack of conflict. If the hero is too comfortable and has nothing to lose, the story is boring. This is true of non-fiction too. Send out a search party, I joke with clients (and myself). Find the conflict and strong-arm it back into the narrative.

Stakes

A pre-requisite of conflict is stakes. What does the character have to lose? There are three types:

Physical stakes: life and limb are the obvious ones but don’t forget about financial crises, professional embarrassment, minor kitchen fires, falling off a bicycle, and arachnophobia.

Emotional Stakes: romantic rejection, sibling rivalry, a tricky friendship, any risk, however major or minor, however real or imagined, to the character’s feelings.

Philosophical Stakes: these are the most difficult stakes to find because they are about core values, like morality and self-identity. They might interrogate society at large (who counts as an insider? can giving ever be truly altruistic? is individualism better than communalism? is democracy impossible?). Philosophical stakes force the reader to grapple with their own values, putting something in peril for them. These tend to be the narratives readers ponder long after reading. Again, this applies to fiction and non-fiction, short and long-form.

A story need not have all three stakes and you can divvy them up among characters. The best narratives, of course, include all three.

What does the character have to lose? Answer that and you’ve found the story’s stakes. How far will they go, what will they do, what will they sacrifice to hang onto those things? Answer that and you’ll discover the plot.

Tension/ Conflict

There are many ways to weave in tension. The obvious way is through a fight, argument, or battle. You can also make your character physically uncomfortable and introduce interpersonal conflict by putting characters at odds with each other.

Dialogue is an excellent vehicle for tension. You can introduce conflict through speech (what is said) and how it is revealed (ie. through summary, indirect, and direct). Summary is a quick summation, vibes only. Indirect gives you a hint of the words. Direct is word-for-word.

Each type of dialogue has a different level of reliability. Any time the character is uncertain or unsure or skeptical of what is being said, they become uncomfortable. That discomfort is tension.

Text is what is spoken. Subtext is everything that’s roiling under the surface, the unspoken words and sentiments that are far more freighted.

Here’s a writing prompt for adding tension: write a scene where one character wants something and the other one won’t give it. And the next time you’re reading something, pay attention to the stakes and conflict. Finding the stakes and conflict in the stories you read is the first step to discovering it in your own.

Need More Help?Here’s a little extra advice on conflict and a multi-part series on dialogue.

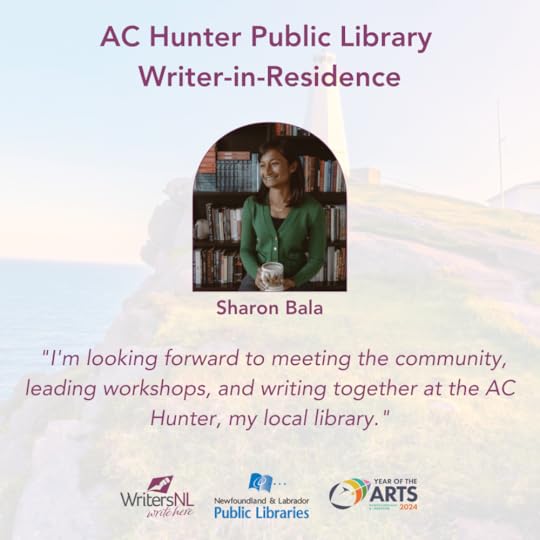

If you’re in or near St. John’s, I’m the Writer-in-Residence at the AC Hunter Library until November 20th and am offering 1:1 consults, running workshops, and hosting write-togethers. There are only a few spots left for individual consults so email me at [email protected] to book yours now.

I moonlight as a writing mentor and manuscript evaluator which means I give constructive feedback on works-in-progress. I’m taking bookings for the spring so get in touch for more info or a quote.

September 4, 2024

In Residence

Exciting news: For a month this Fall, I’ll be the Writer-in-Residence at the AC Hunter Library. Between Tuesday, October 22 and Wednesday, November 20th, I’ll be running four workshops, hosting group writing sessions, and reading/ offering feedback on your prose during twice-weekly office hours. Everything on the program is free, in-person, and open to writers of all levels.

Better still, I’m only one of four writers who will be in residence at different libraries in the province. This special initiative is part of NL’s Year Of The Arts. Who knows if we will ever get this opportunity again so if you’re a local writer or writing-curious, take advantage!

Write Together SessionsThese low-key, zero-pressure writing sessions will be held on Tuesday evenings and Wednesday mornings, October 22 - November 20th, on the third floor of the AC Hunter Library (125 Allandale Road, St. John’s). They are open to aspiring and practicing writers of all levels. Bring yourself and your implements (paper, pencil, computer, whatever you prefer) and I’ll provide optional prompts and a timer to keep us on track. Tandem writing is a wonderful way to break writer’s block and get you in the zone. It also helps build the muscles of focus and attention. If you’ve been struggling to firm up a writing practice or have a story you desperately want to commit to paper, these sessions are for you. No advance registration is necessary.

Office Hours & FeedbackIf you’re a writer with a short piece of fiction or non-fiction, I am offering feedback (on up to 2,000 words) through one-on-one meetings during my twice-weekly office hours. Due to time constraints, there are only 25 spots so email [email protected] to submit your writing and book your 30 minute time slot.

WorkshopsI’ll be running four in-person workshops. Three will be geared toward adults and one is specifically for teens. These are free events but space is limited. More details for each workshop are on my Events Page. To register phone the library at (709)737-3950.

Here’s the schedule for my time at the AC Hunter:Tuesday, Oct 22

5pm-6:30pm: write together session

6:30-8pm: office hours

Wednesday, October 23

9:30 - 11am: write together session

11am - 12:30pm: office hours

Tuesday, October 29

5pm-6:30pm: write together session

6:30-8pm: office hours

Wednesday, October 30

9:30 - 11am: write together session

11am - 12:30pm: office hours

Saturday, November 2nd

Story Dissection Workshop: 10:30am-noon

Tuesday, November 5

5pm-6:30pm: write together session

6:30-8pm: office hours

Wednesday, November 6th

NO WRITE TOGETHER OR OFFICE HOURS

Great Openers Workshop: 6:30-8pm

Thursday, November 7th

Creative Writing Workshop for Teens: 3:30-5pm

Tuesday, November 12th

5pm-6:30pm: write together session

6:30-8pm: office hours

Wednesday, November 13th

9:30 - 11am: write together session

11am - 12:30pm: office hours

Saturday, November 16th

Revision Workshop: 10:30am-noon

Tuesday, November 19th

5pm-6:30pm: write together session

6:30-8pm: office hours

Wednesday, November 20th

9:30 - 11am: write together session

11am - 11:30am: office hours (NOTE: shorter office hours on this day)

October 5, 2023

Blurbs

Recently, on CBC’s Commotion podcast. there was a dishy chat about blurbs. It’s worth a listen if you’re an aspiring author or have a first book deal or are curious about what it means to get a more established author or Barack Obama to say one nice word* that can be printed on your cover.

Most of us need blurbs but the relationship is fraught. It’s amazing to receive any sort of advance praise, especially when you’re deep in your feelings in that final stretch right before a new book comes out. But blurbs require hours of free labour. And the galling part is it’s impossible to do the (unpaid) job without toppling into cliche hell. To wit…

“A confident and lyrical debut penned by an author of uncommon talent.” (for Heather Nolan’s This is Agatha Falling)

“A vivacious debut from an author to watch” (for Jamaluddin Aram’s Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on a Wednesday)

“Clever and insightful, this book is a sheer delight.” (for Kerry Clare’s Waiting for a Star to Fall)

“A masterful collection, written with so much veracity, you’ll swear every word is true.” (for Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife)

I once wrote “laugh-out-loud funny” in a blurb and was asked to please find a synonym because all the book’s endorsements included the same banality. In our collective defense: Shashi Bhat’s The Most Precious Substance On Earth is very funny and did make me guffaw.

Okay, so here’s a secret: I’m 95% more likely to consider a blurb request if it comes from a third party - agent, editor, publisher, publicist etc - instead of the author. I say no a lot more often than I say yes and the whole proposition is less fraught if it goes through a middleman.

But here’s the other thing: there’s more than one way to champion a book. I talk about books, write about books, recommend books to friends and family and clients and students. Whenever I lead a workshop, I pull passages from at least three or four authors. Just because I say no to a blurb, doesn’t mean I won’t find another way to be a cheerleader for the book.

*My favourite blurb always and forever is the one Obama gave Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad: “terrific!”

September 29, 2023

Copy. Write.

Ten years ago a guy broke into our house and stole my laptop which contained all my short stories plus research and early scenes from a project that would eventually become The Boat People. I wasn’t backing anything up at the time (I know) so it was a blow.

But that was nothing compared to the dread and rage I feel in the dystopian present where a cylon is hoovering up our literary souls in order to teach itself how to shit formulaic turds.

Maybe I’m naive or in denial but I’m not worried about AI taking my job. I’m not prolific enough, for a start. And my work is too nerdy. The Boat People was a fanfic of the Refugee Law text book. Who wants an AI version of that? The new novel-in-progress is even nerdier. Even nerdier.

What I mourn is the theft. Stories come from a deep well of experience, memory, and freighted emotion. It’s a collage of personal insecurity and insight. I remember the moment when the character of Grace finally clicked and I realized her primary motivation was fear. It happened when I was in the middle of a fraught conversation about Syrian refugees that made me feel sick for days afterward. There’s a scene early in The Boat People where Priya is in an elevator and her name is being butchered. My first year in Canada was grade three. The teacher asked me to repeat my last name (it was longer then - Balasubramaniam) so many times out loud in front of a class where I was the new kid that I came to hate it. I had never known my name to be a burden before that. I had never hated my name.

The character of Savitri is an homage to my Appama who, like Savitri, was fair-skinned. She fled Burma as a child on foot to Sri Lanka. Her brother died along the way. In Point Pedro, she was so fair compared to other girls that the family was afraid she’d be abducted and her step father slept by the front door with a gun. I can’t remember if that detail made it into the final cut of the book but that’s part of Savitri’s biography.

These are my characters. They come from me. They come from my people. They are part of an older, wider community that is historic and contemporary because of course I am also taking from experiences I have or things people tell me or things I overhear or intuit by watching and listening. I write human stories and AI cannot do that. But AI is really fucking good at stealing. It robs our work, our words, our ideas, our stories, our syntax, our phrases. But it’s also pillaging something more personal and that’s the worst, most perverse, most inhumane part.

On the morning of the break in, we woke up to the sound of a stranger rummaging through our cupboards. The imagination defaults to the worst case. Mine went to heavy boots. Big man. Weapons. The thief turned out to be a scrawny eighteen-year old with glasses. The things he stole were found nearby, all unharmed, including my laptop. His sentence was nine months in prison. What do you think Zuckerberg et. al deserve for their grand larceny?

September 22, 2023

The one about friends

This one isn’t about writing.

Last week everyone was talking about that article in The Cut. The one about friendship and children. You know the one. For some reason the discourse remains fixated on children, as if their arrival is the only thing that can transform relationships. But we all lose touch with work friends after leaving a job, school friends after graduation, neighbourhood friends after a move, parent friends after the kids grow up or apart. We shed relationships like skin and if we’re lucky, and put in the effort, make new ones. It’s curious that the level of bitterness heaped on kids doesn’t rear its head when a friend moves or gets in a new relationship and goes MIA.

It’s like this. You’re rowing your boat and along the way you come alongside someone else in their boat. They’re going your speed, seem to be on your wavelength, and for a time it is smooth sailing. Then something happens - a big move, a career change, a new relationship, a break up, illness, whatever - and the other person can’t row as hard. You can wish your pal well and move on. Some friendships aren’t meant for the long haul and that’s okay. You can resentfully flip them the bird as they drift away. Or you can hitch their boat to yours and give them a tow.

The true love, long haul, till-death-do-us-part, Big Friendships are the ones where two people take turns giving each other tows without keeping score, without expectation, on faith, trusting that when it’s your turn, you can put those oars down, someone’s got you.

Sharon Bala's Blog

- Sharon Bala's profile

- 134 followers