John Elder Robison's Blog, page 14

January 3, 2012

Snakes Attack When You Least Expect It

You know, I have had a lot of strange experiences during my lifetime. Some are shared with other people. Others are not. Until today, I never thought I'd meet someone else who was attacked by a Flying Snake. But folks, here he is:

January's Guest Blog, You Can Choose Your Own Adventure, by

David Finch

When

I resigned from engineering to write full-time, my first order of business was

to convert the spare bedroom in my parents' house into my own, personal office

space. I'm married, I have two kids, and

I have my own house, but my parents still work -- my dad is a farmer and my mom

a teacher -- so their house is quieter than mine, and thus more conducive to

thinking.

Their food is also free, and their

neighborhood is prettier. So why

wouldn't I sponge off of them? When I

need to clear my head at home, I might go for a walk and see, at best, a dog

peeing on one of the scrawny saplings our developer planted along the sidewalk,

or half a dozen kids zipping around on motorized scooters. Images that don't inspire my best thinking.

But my parents' house is situated in

a sleepy rural neighborhood in which sizable new homes are surrounded by

impeccably landscaped yards and massive old trees. Down the road a little way is a pond, and

beyond that, some woods. At the pond,

I'm guaranteed to spot a handful of turtles mingling on a log, a nervous

muskrat trolling along the shoreline, or half a dozen hawks riding air currents

overhead. It's peaceful, and my mind can

wander as needed, which is usually -- usually -- a good thing.

I was out for my afternoon walk one

day last September when I spotted a dead snake lying belly-up on the side of

the road. He wasn't big, this snake,

maybe eight or ten inches long if you stretched him out. I gasped, leaping sideways into the road to

avoid stepping over it -- leaping without looking into the road where cars

drive, to avoid stepping over a tiny, dead snake.

Here's the thing: I hate

snakes. Or rather, I fear them. I always have. In the second grade, my class watched a film

strip showing the gruesome manner in which a snake kills and consumes its prey:

you're either bitten to near-death and swallowed, or squeezed to near-death and

swallowed. That was it. Those were your options when it came to being

attacked by a snake.

From that day forward, I understood that the

only thing a snake is supposed to do in life is to kill -- to strike its

victim, savagely and horribly, with precision, then detach its jaw, and

subsequently devour the twitching body of whatever animal or second grader it

just attacked. I diligently limited my

experience with snakes to the pages they occupied in my parents' Encyclopedia

Brittanica. Even there, confined to the

page as two-dimensional images, I was terrified by them. Their horrible bodies, their vicious fangs,

those cold, lifeless eyeballs. I could

look at a picture of a rattle snake for maybe ten seconds before I got spooked

and had to turn the page, fearful that it might come to life and chase me around

the house.

If I had to guess, I would say that

the snake I encountered lying dead in the road last September was a garter

snake. Totally harmless, not a creature

to fear. There was nothing particularly

remarkable about him, either, except for the fact that his body, despite having

expired at some point, was still perfectly in tact, and, curiously, was resting

upside-down. I took a moment to consider

how this might have happened, and drew a blank.

Was he showing off to his friends when he realized he couldn't get

himself right-side-up again? Had he died

while they went for help?

I tossed a small rock at him to make

sure he was actually dead and not just trying to deceive me, and when he didn't

react I moved in for a closer look. I

felt as though I was walking on a tight rope between two skyscrapers; my hands

were sweaty, my mouth dry and cottony.

All this, in response to a lifeless snake no longer than my flip-flop.

I expected I might find some guts or

gook or something, but there was none.

He hadn't been flattened by a car or bicycle, and there was no trauma on

his flesh to indicate he'd been attacked by a predator or pawed to death by a

playful neighborhood dog. His body just

lay there, his lime green underbelly glistening in the sun.

I continued on my walk, but couldn't

stop thinking about the snake. How did

he end up like that? I wondered. And

suddenly it hit me: Had he been dropped?

I was halfway to the pond when my

theory began to take shape: A hawk must have nabbed the snake and taken him for

a little ride before losing his grip and dropping him a few hundred feet to the

pavement below. Or perhaps the snake

wriggled free in an instinctual and ironic attempt to escape the clutches of

his captor, only to realize how screwed he was as he plummeted to his

death.

My thinking continued: As light as

the snake must have been, a fall from a substantial height wouldn't necessarily

splatter him, but it would certainly be enough to kill him. Wouldn't it?

Yes, he must have escaped the clutches of a hawk, fallen from a great

distance, and landed right there where he died.

That's the only way it makes sense.

I was quite satisfied with my

sleuthing and had all but moved on when I realized the terrible implications of

my theory. If the snake had been dropped

by a bird as I suspected, this would mean that at any given point in time, a

fucking snake could just fall unexpectedly from the sky and land right on my

head. I had never in my life considered

this to be a real possibility until that moment, and just like that, I had a

new fear.

Suddenly, the road, the ditch, the

neighbors' driveways, the trees—the entire landscape—was just crawling with

imaginary snakes—which are, without a doubt, the worst kind of snake. In fact, the only thing more terrifying than

a real snake is an imaginary snake, because unlike a real snake, the imaginary

kind always appear out of nowhere without any warning. Imaginary snakes never slither off into the

grass to avoid getting stepped on.

Instead, they chase you at high speeds knowing that, at some point in

your panicked sprint, you'll stumble and fall.

And that's when they'll drop from the sky to wage their brutal

assault.

I knew at that moment that I would

have to find a new place to write.

This is what happens when obsessive

thinking is married, as it is in my neurological construction, with a vivid

imagination. I tend to get pulled into

these absurd and terrifying rabbit holes, unable to snap out of it and think

about anything else, for hours or even days at a time: What is my hotel room going to look like when

I go to New York next week? Kristen said

she'd be home at 4:00, and it's 4:02, where is she? Why was that store clerk so rude to me? And it's not exactly my brain's fault when I

get stuck on these thoughts, but mine.

I may not be able to control which

thoughts pop up at any given moment, but I can decide, consciously, whether or

not to indulge them. I can't choose to

never again think about a snake, but I can choose to create a ridiculous storyline

involving snakes being launched at me by hawks, and apparently I can even

choose to accept that storyline as a likely reality. Even if it means scaring the crap out of

myself, despite the fact that I don't really enjoy feeling scared.

So, why wouldn't I use my powers of

creativity and self-persuasion to imagine a scenario in which snakes don't fall

from the sky? A scenario in which snakes

do slither off into the grass for fear of being trampled? In other words, why do I sometimes choose to

believe silly, illusory thoughts, rather than reality -- which is, by

definition, real?

I don't have an answer to these

questions. Fortunately, though, it

doesn't really matter why I choose to believe one thing and not another; all

that matters is that I can choose -- that much I can control.

So I'm working on it. I'm practicing interrupting the cycle of

terrible, worrisome thoughts with an act as simple as taking a breath, and I'm

also practicing not getting pulled into the rabbit hole to begin with. Two very different endeavors that are equally

worthwhile, both of which are totally within my control.

And I must say, it's going

fabulously. I still obsess over hotel

rooms for some reason, but no longer am I convinced that snakes can rain down

on me from the heavens; I now carry an umbrella only when it's raining.

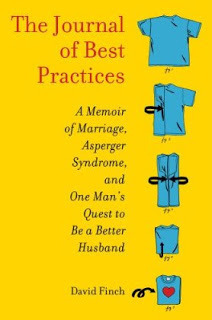

About the author: David Finch's essays have been published

in The New York Times, Slate, and Psychology Today. His debut memoir, The Journal of Best

Practices: A Memoir of Marriage,

Asperger Syndrome, and One Man's Quest to Be a Better Husband, was published by Scribner on January 3,

2012. David lives in northern Illinois with his wife, Kristen, and their

two children. Please join David on facebook.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on January 03, 2012 13:01

January 2, 2012

Looking forward at the autism spectrum

Where is this autism spectrum of ours headed?

It's the time for New Year resolution, and mine is that we

autistic individuals rethink how we present autism to the public.

By now you've likely read that the latest version of the DSM

guide proposes to merge Asperger's, PDD-NOS, and all other autistic conditions

into one diagnostic category, to be called Autism Spectrum Disorder.

A number of parents and advocates for people with very

severe autistic impairment have criticized that move, saying it will render

people with both severe autism and intellectual disability almost invisible.

Some even feel the traditional autism diagnosis has been

"taken away from them," to be replaced by a broader, more Asperger-like

diagnosis.

I agree with those sentiments.

Thirty years ago, the largest percentage of kids diagnosed

with autism also had some degree of intellectual disability and were by any

standard, near 100% disabled. Today, the

majority of kids diagnosed with autism do not have intellectual disability and

most will grow up to live and work independently. That's not because the number of kids with

intellectual disability has dropped; it's because the autism diagnosis is

applied to a much broader swath of population.

To understand how this has happened one need only look at

how the phrases used in the definition are interpreted. For example, "Substantial communication

impairment," was at one time a euphemism for, "unable to have a conversation." Today it can mean that, or it can mean, "has

difficulty reading body language and interpreting unspoken messages." The range of meaning of those three simple

words has expanded tremendously.

To a lay person, an autistic person who cannot hold a normal

conversation presents totally differently from one who is highly articulate,

but misses subtle social cues and facial expressions.

Yet that is the reality of the autism spectrum as we know it

today. We have a large and growing

population of very different individuals, under one very broad diagnostic

umbrella.

As the autism spectrum expands to encompass more people with

progressively greater verbal and written communication skills, those

individuals have begun speaking for themselves.

By doing so, they are altering the public's perception of what or who an

autistic person is or may become.

This reshaping of perception has moved the public's concept

of autism higher on the IQ range, with more and more people seeing "autism" as

a euphemism for "eccentric geek," or, "genius," which is most assuredly is

not. Popular television shows like

Parenthood and Big Bang Theory reinforce that trend.

At the same time, the population of people with intellectual

disability and severe autistic impairment remains fairly constant. Those individuals are not generally able to

speak for themselves. They are most

often out of the public eye, and they may rightly feel they are rendered nearly

invisible by this change in perception.

What might we do about this?

For starters, all of us who occupy the more verbal and

articulate end of the autism spectrum can keep in mind that it is a spectrum,

and some of our fellow spectrumites are much more verbally challenged than

we.

Every time a person with milder autism speaks of his own

challenges, those words add to the body of information the public uses to define

autism. The more we move that balance

from disability toward eccentricity, the more we harm our cause, albeit

unwittingly and with the best of intentions.

When self-advocates' autism talk shifts primarily to rights

and entitlement, the need for new therapies, treatments, and services is

forgotten. When we focus on entitlement,

we create the impression that our problems can be solved by legislative action,

much like the civil rights laws did in the sixties.

Entitlement and equality are great ideals, but they do not

remediate disability. We must not lose

sight of that fact, when building autism awareness. We are not equal people fighting for equal treatment. We are disadvantaged people fighting for

remediation of our disability, and the opportunity to be treated fairly by

society. That is a very different

proposition.

Autistic brain differences may indeed be a component of

creative genius, but they are more often a contributor to significant

disability. We need to balance our own

desire to "think positive about our potential" with the need to keep the public

more in touch with current reality and the services we so desperately need.

The autism spectrum still includes a large population –

several hundred thousand in the US alone – who currently have no realistic hope

of substantial employment. That is a

tragedy. And it's not because they are

discriminated against. It's because they

are disabled. Not only that, they are

disabled for reasons we don't understand and in ways we don't know how to fix.

I suggest that is the thing we need to fight for the most,

as we build autism awareness. We need

help remediating the many, varied, and often profound disabilities that touch

those of us with autism. Only then can

many of us fully integrate with society in the way we all desire.

For this New Year, I wish for all of us to keep our more

challenged brothers and sisters in mind whenever we discuss autism with the

public. It's great to be upbeat, but for

many, autism remains a crippling disability.

The fact that some of us emerge from disability as an adult does not

make the challenges faced by others who do not any less real or meaningful.

If we are to be a truly great society, we must aspire to a

great quality of life for all, and that means those of us who cannot speak for

themselves must not be forgotten in that quest.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on January 02, 2012 18:09

December 24, 2011

Christmas

Are you ready for Christmas once again? I'm getting there . . .

When it came time to wrap the presents for tomorrow, I found

my supply of coal depleted. Nothing

remained but a few crumbs. Local urchins must have been pilfering when I wasn't

looking. Something had to be done, and

fast.

I drove a few miles north to an area where the railroad runs

close to Northeast street. Parking the

car in the weeds, I set off down the track.

A mile or so later, my objective came into sight: the old University coaling station.

I walked down the line until I reached the end, where years

of coal cars had covered the ground in fine black gravel. Bending down to scoop a few handfuls, my eye

was drawn by a glitter just ahead.

Slag.

I've walked thought that area countless times, and realized

I had missed it all those years.

Millions of pounds of coal had arrived through that siding, all to be

burned at the University heating plant.

So what happened to the residue?

The ash and slag were cleaned out of the furnaces on a regular

basis.

Some of the ash was used by the Mortuary College, to train

future crematory operators. Others in the same program practiced disposal,

spreading the ash in a fine layer over the School of Farming's fields.

They never did find a use for the hard, glittery slag. In the end, the bigger chunks were piled next

to the coal, and loaded onto trains for disposal somewhere out West. Somewhere in the desert, whole neighborhoods

have been built on University slag, held together with fine cemented fly ash.

The power station is long closed, replaced by an efficient

nuclear reactor, but the siding remains, rusting away slowly. The brightest gems of slag are gone, but I

found enough glittery bits to make a special Christmas indeed.

Combined with a few handfuls of fine pebble coal, the effect

will be memorable.

I'm off to get ready.

The kids are coming soon.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 24, 2011 14:44

December 23, 2011

Toys

This morning one of the guys at work showed up with a doll

for his kid. Look, he showed me, it pees

and poops! I turned it over and sure

enough, it did. Looking at the box, I

saw the thing was a product of a major toy company, to boot.

It reminded me of some of the other toy ideas that passed

before our eyes, back when I worked in R&D at Milton Bradley.

For example, there was Baby Black And Blue. BB and B had a special plastic skin, that

changed color if you grabbed her by the legs and whacked her hard against a

tabletop. Just like a real baby.

That one never saw the light of day, or the light of stores.

Then there was Feed the Alligators. That was a two person game, where one kid

operated the mouth on a wooden alligator, and the second kid operated a little

seesaw that launched little babies toward the water.

I remember playing that game for real, when the big bully

kids would launch me and the other tykes off our seesaws. We learned to exit fast when we saw them

coming, lest we go aerial.

F t A was actually sold, for some years. You can probably buy a copy yourself on ebay.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 23, 2011 13:08

December 21, 2011

A Gift and an Opportunity for Christmas

Have you ever looked at the men and women who ring bells, accept donations, and hand out little gifts outside our malls and thought: I wish I could do that! Help the needy and raise some cash for a drink or even a gift?

Well, now you can. All you need is a can for the money, and a sack of Perfect Gifts for the Needy. Coal is widely recognized as the stocking stuffer par excellence, and of course it's good for blacksmithing, home heating, and even power generation. In its natural form, it's a smooth and beautiful black, waterproof and durable. A gift for the ages. Think of each stone as a diamond that didn't quite make it.

My friends at Penn Keystone have all you need. They can sell you fifty pounds, bagged, for less than thirty cents a pound. Compare that to the prices at Toys R Us, or Macys! Fifty pounds of anything from those stores will cost far more than fifteen measly dollars!

Give them a try; you won't be disappointed. Remember - Real Santas use Real Coal. American Coal. Accept no substitutes.

http://www.penncoal.com/wst_page4.html(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 21, 2011 17:27

December 20, 2011

On the road with April Wine

Every country has it's big rock and roll bands. We Americans assume the bands that are big here, are big all over the world. In some cases, that's true. But every country has its own musicians, some of whom are very popular at home while being totally unknown here.

That's the case right here in Canada, where April Wine is huge all over, yet few in the USA have ever heard of them. Founded in the 70s they are still on tour today.

April Wine will always be special to me, because I turned 21 on the road with them, riding the ferry to Newfoundland the night of August 13, 1978.

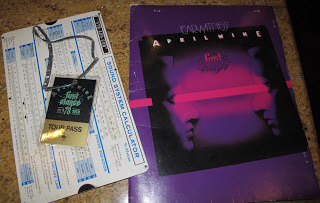

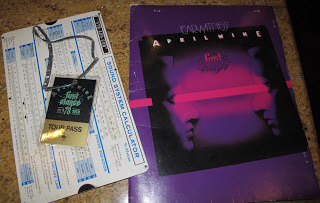

Yesterday I was going to through old papers, and I found my April Wine tour schedule, my tour pass, and an old sound system slide rule calculator.

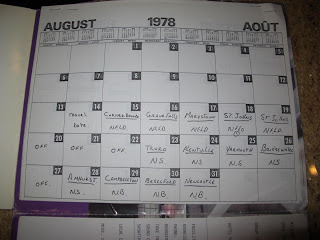

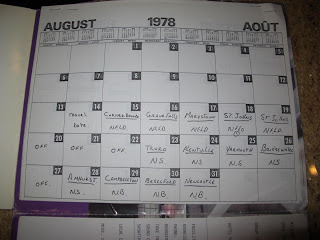

Lots of people think touring with a band is glamorous, but it's hard, hard work. This tour had gone on the road in July, touring the Calgary Stampede, and hockey rinks across eastern Canada. After a short break, the tour resumed August 15 at Humber Gardens, a big barroom in Cornerbrook, Newfoundland. We played till midnight, then tore down the gear, packed it, and hauled everything through the night to the next night's show at Grand Falls. We did another one night stand there, and played Marystown the next night. Then we got a break with two nights at Memorial Stadium in St. Johns.

After that, the tour calendar optimistically says "OFF" for three days, but what we really did was pack all that gear into cases and ferry it to Nova Scotia for the next leg of the tour. It may have been "OFF" for the musicians, but it most assuredly was not off for us.

Most all our shows sold out; the tour was a huge success for the band. It was hard work for me, and everyone else who made it happen.

Canadian readers will find a story about April Wine in the opening of Be Different, which goes on sale across Canada in paperback this March.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

That's the case right here in Canada, where April Wine is huge all over, yet few in the USA have ever heard of them. Founded in the 70s they are still on tour today.

April Wine will always be special to me, because I turned 21 on the road with them, riding the ferry to Newfoundland the night of August 13, 1978.

Yesterday I was going to through old papers, and I found my April Wine tour schedule, my tour pass, and an old sound system slide rule calculator.

Lots of people think touring with a band is glamorous, but it's hard, hard work. This tour had gone on the road in July, touring the Calgary Stampede, and hockey rinks across eastern Canada. After a short break, the tour resumed August 15 at Humber Gardens, a big barroom in Cornerbrook, Newfoundland. We played till midnight, then tore down the gear, packed it, and hauled everything through the night to the next night's show at Grand Falls. We did another one night stand there, and played Marystown the next night. Then we got a break with two nights at Memorial Stadium in St. Johns.

After that, the tour calendar optimistically says "OFF" for three days, but what we really did was pack all that gear into cases and ferry it to Nova Scotia for the next leg of the tour. It may have been "OFF" for the musicians, but it most assuredly was not off for us.

Most all our shows sold out; the tour was a huge success for the band. It was hard work for me, and everyone else who made it happen.

Canadian readers will find a story about April Wine in the opening of Be Different, which goes on sale across Canada in paperback this March.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 20, 2011 06:10

December 13, 2011

Love is blind - Marriage is the eye-opener

This afternoon, I'm pleased to present a guest blog from my friend and fellow author David Finch, whose Journal of Best Practices makes its debut in bookstores in just three more weeks . . .

When

people meet me for the first time, they're often surprised to learn that I have

Asperger syndrome. "Oh, my," they say,

sometimes slowly and clearly, as though they're now addressing a child. "It is really remarkable how well you're able to handle yourself

socially."

As compliments go, it's not so

bad. Still, I can't help but feel a

little like an unfrozen Neanderthal when I hear comments like that. "You mean to tell me you're only

thirty-four years old and you managed to come here all by yourself?" The implication is that two minutes ago

I was just another dude standing around in a sport coat, smiling unexpectedly,

but now that I've outed myself, I'm Asperger Guy, and it's a wonder I haven't

been yapping the whole time about pygmy fruit bats or the history of the shoe.

What

can I say? People are bound to be

surprised. One of my special talents is

masking certain behaviors, a skill set I've been cultivating since childhood,

when began my lifelong career of wanting to blend in. Even I didn't know I had Asperger's until I

was thirty years old; the prevailing diagnosis throughout my early life was

that I was peculiar. Talk to me long

enough, or catch a glimpse of me lumbering around the cocktail party, and you'd

find this assessment still to be fairly accurate. But at first glance, you might not call it

Asperger's. This is not uncommon. Some with Asperger's may appear more or less

not-Aspergian depending on the circumstances.

I could possibly elude a diagnosis if I assumed the right character

while talking to a psychologist for an hour or two.

My wife, Kristen, knows this all too

well. We had been friends for years—I

was always that special (dorky) friend of hers, the quirky one who made her

laugh in a certain way that no one else could—and one day, we found ourselves

in love. We dated for a year, a period

of time that, in some ways, felt like a twelve-month-long audition. Be cool, I told myself, roughly ten-thousand times a day. Look normal. Act normal.

We got engaged, and still I did

everything I could to impress her, because, as I understood it, that's what a

person did when they landed themselves a fiancée. I showered Kristen with affection and praise,

went out of my way to act supportive, and never once voiced a negative thought

or feeling. What was not to love about that guy?

After we were married, and we were

living together around the clock, Kristen began to understand exactly what was

hard to love about that guy: he wasn't entirely real. By our third anniversary,

the illusion I'd created had been shattered, and Kristen found herself married

not to the husband she'd always wanted, but to a husband who had no idea how to

go with the flow. A husband who lost his

temper whenever his concentration was disrupted—even when it was disrupted by

an act of affection, such as a kiss or a simple hello. A husband who couldn't show her the kind of

support she needed.

Despite the fact that she had been

working with children with autism for several years, Kristen hadn't recognized

my mixed bag of baffling behaviors and frequent man-tantrums as Asperger's (of

course, no one else, including me, had recognized this either). We had been married nearly five years before

her suspicions reached an apogee and she realized I could actually be on the

spectrum. Some are amazed by this, but

it does not surprise me at all.

A toad analogy, if I may. I've been told that if you toss a frog into a

pot of boiling water, it will immediately try to escape, but if you place a

frog in a pot of water at room temperature and gradually bring it to a boil,

the frog will not try to escape; it'll just boil to death. (I don't know who on earth conducted these

experiments, but I like to think it's true.

We can also assume that I'll be the one in hot water for making my wife

a frog in my own analogy...)

Marriage can be a slow boil. When you're married, and things aren't going

so great, the threshold of pain and drama and wackiness tends to creep up

imperceptibly as you go about your daily lives.

If, when you were blissfully dating, you could somehow fast-forward to a

period in your marriage when that threshold of pain is unfathomably high—five,

ten, fifteen years into the future—you would experience the darkness all at

once, and you might decide to walk away from the relationship, to leap from the

pot. It would be that alarming. "Good lord, is this what our marriage

is going to look like?! Welp, nice

knowing you, do not keep in touch." But life doesn't work that way. Instead, you just sit in the pot, day after

day, and boil to death, acclimated for better or for worse to the suffocating

conditions.

There is another reason we wouldn't

have thought to call it Asperger's sooner: I had never expressed to Kristen

just how challenging certain situations were for me. Like how difficult it was to navigate social

interactions, how exhausting it was for me to be "on" around other people, or

how upsetting it was whenever my routine was disturbed. I hadn't spent a great deal of time

contemplating these things about myself.

All I knew was that I seemed different from other people, yet prior to

my diagnosis I just wanted to fit in. I

wanted to seem, for lack of a better term and knowing full well that a word

such as the one I'm about to use can swiftly, if unintentionally, stoke the ire

of commenters everywhere, normal. As a

guy who assigned unique personalities to numbers, was it asking too much to

seem normal? I mean, who wants to think

of themselves as being inferior? Who

wouldn't feel inferior if they were being mocked on a regular basis, even as an

adult? Who has the presence of mind to

say yes to their freaky, extraordinary selves, especially if they don't know

it's okay—nay, advantageous—to be different?

So, how could Kristen have known

what it was like to be me? I barely knew

what it was like to be me—I didn't even know there was a clinical name for

being like me.

When she realized how many similarities I

had with Aspergians, Kristen sat me down and guided me through a very informal

evaluation. Though I am grateful to be

married to someone who doesn't spend her days regarding me through a diagnostic

lens, I'm glad that Kristen instinctually pieced it together and invited me to

participate in the evaluation. A person

can learn a lot about himself when he answers more than a hundred questions

designed to reveal precisely how his mind works. For the first time I understood who I am. And Kristen finally understood, too.

Until we went through that exercise,

she could not possibly have known just how difficult it was for me to adapt to

things, or how great a challenge it was for me just to understand how to be

responsive to her needs. Or, in her

words: "I never could have imagined how hard it sometimes is for you to simply be."

That's how Asperger syndrome can so thoroughly

destroy a relationship that at one time seemed invulnerable. If it's well-hidden, and you're not

specifically looking for it, the condition can reveal itself slowly, one misunderstanding

and baffling meltdown at a time. But for

Kristen and me it's no longer hidden, and we used this knowledge of the

so-called disorder to rebuild our marriage.

With my diagnosis she found patience and understanding, I found

self-acceptance and the will to learn to manage the behaviors that strained our

relationship, and together—together—we are finding our way to the marriage we always wanted.

And it makes me wonder, as I sit

here scripting tomorrow's inevitable didactic lecture on pygmy fruit bats: How

many of us are struggling with something that reveals itself in such cruelly

deceptive ways? How many of us are

plainly misunderstood, even by those who know and love us best?

AUTHOR BIO:

David Finch is an author and lecturer. His debut memoir, THE JOURNAL OF BEST PRACTICES (Scribner;

January 3, 2012) is available for pre-order now. David lives in Illinois with his wife and

their two children. Please join him on Facebook.(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 13, 2011 13:29

December 11, 2011

Some thoughts on the trades

This weekend I finished another excellent book about our

economy, and how we might recover from recession. One of the suggestions was that we should

become better educated, as a society. To

bolster that point, the author talked about college graduation rates, and the

limited prospects for non-college-graduates who end up with low paying service

jobs.

Where are the trades, in that writer's mind?

I can just hear the answer now . . . Trades? What are trades?

All too often, writers divide the world of work into

"educated and professional" labor performed by college graduates, and "minimum

wage service work" performed by the unwashed masses; those of us who did not

make it out of college or perhaps even out of high school.

That depiction does a great disservice to our young people

as they contemplate their future career paths.

For the trades still offer tremendous opportunity, and they are

overlooked more and more today.

So what are the trades, you ask? Trades are specialized jobs that are taught

by doing. People who work in the trades

use both their hands and their minds to reason through problems and produce tangible

results. In years past you learned a

trade by being an apprentice. Today, you

might learn a trade at a trade school, or academy. And some apprentice programs still

exist.

Examples of trades are:

Carpenter

Auto, truck, or airplane mechanic

Computer service technician

Medical equipment service technician

Plumber

Electrician

Heavy equipment operator

All of those jobs require substantial skill that is

developed through both study and practice, and all have different levels. One starts out at low wages as an apprentice,

while masters make as much as most people in "professional" jobs.

The next step up from being a master is to own a small

business that employs other tradesmen. Examples are my auto service company, or

a local electrical contractor. Owners of

successful trade business can make as much or more money than even high-level

professionals, like doctors or lawyers.

Yet the path to success does not generally pass through a

college and it is often overlooked.

There are three hundred million people here in America. It's tradesmen who construct the places where

we live. Tradesmen bring us the electric

power, and the plumbing. Tradesmen fix

our cars and trucks. The beauty of the

trades is that they are not going anywhere.

No one is outsourcing those jobs to India or China.

It's true that the trades change. The job of fixing cars has changed

tremendously over the past twenty years, as has the job of wiring a house or

even installing plumbing. But everything

changes. We all have to learn and adapt.

In some cases, fewer workers are needed in a given

area. Construction trades are a good

example of that today. With the housing

collapse, we have a surplus of tradesmen who know how to work new

construction. Yet we still have jobs in

other trades, like auto repair, and we even have jobs for carpenters, plumbers

and electricians in repair and maintenance.

I find working on things I can pick up and handle very

satisfying. I know many other tradesmen

feel the same. I like to fix something,

see it work, and know it's a job well done.

That sense of personal connection and satisfaction is missing in all too

many jobs today.

Tradesmen keep our world running. When your lights go out, you don't turn to an investment banker for help.

So why are the trades overlooked and dismissed? Maybe it's time for a second glance . . .

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 11, 2011 19:06

November 8, 2011

What to do when you tangle your backhoe in the electric lines

This past weekend we had unprecedented damage from an early

snowstorm. Trees were down across all

the roads in town, and many took powerlines down with them. I had to clear a dozen or more large trees

just to reach the highway, less than half a mile from my house.

I used the front end loader on my tractor to break up the

tree jams, and pick up the brush and move it aside so cars could pass. Anyone who's ever run a loader knows that's

heavy and dangerous work as the trees bend and snap. You're glad to be in a roll cage enclosed cab

with some of those limbs come back to whack you in the face!

To clearing the road I'd scoop under a load of tree debris,

lift it high, and dump it in the woods.

That process went along uneventfully until I picked up a load of brush

that was tangled with bare electric power lines. There are lots of stories online telling you to stay away from power lines. There are very few stories that talk about what you should do if you get up close and engaged with them. Today, I'd like to share my thoughts with you.

The conventional wisdom says that it's fatal to contact live

electrical power lines. That is

certainly the case much of the time, but not always.

If you hit live power lines with a loader, backhoe, or

crane, and you are inside an enclosed cab on the machine, you can probably

emerge unscathed, provided you keep your wits about you and follow these

steps.

When your machine touches the line, it immediately becomes

energized to the voltage in the wires.

If you are sitting in the cab, you get energized too. You don't actually feel anything but a

tingle, as no current is flowing through you, but you are suddenly in a very

dicey position.

As long as you remain in the cab, the wires can't touch you,

and the current flows through the metal of the machine. If you get out of the cab, or a wire gets

in, all that changes. If you touch anything outside the cab, the power line current will flow from the cab frame, into you, and out of you into whatever you touch. That's almost always lethal.

Touching a tree or anything outside your machine while in the cab will kill you. Touching the ground in an attempt to escape the cab will kill you too. So stay inside, windows shut.

That's how most people who have accidents on construction

equipment get killed. They hit a line,

and then jump off the machine. That's

usually a fatal error. The ground under

the machine is energized as the current flows through the wire, into the

machine, and into the surrounding earth.

The dirt within five to ten feet of the machine is going to be energized

to a dangerous level. So you can be safe

in the cab, but dead if you jump on the ground.

The wires present another danger. If the wire is outside, touching your loader frame,

you are safe. If the wire gets inside,

or touches you, you are toast. So don't

open the windows or doors.

If anyone sees you in this fax, wave them away, but do not

open the doors. If they approach you,

they are likely to be electrocuted by the field you are currently immersed in. Hopefully, no one else is around you.

The final danger is that the energy in the wire will disable

the machine, leaving you unable to escape.

When the energy flows into the machine's steel frame, it has to go

somewhere. That somewhere is ground,

through the steel tracks or rubber tires that the machine sits on. That point of contact with the ground becomes

a hot spot, both figuratively and literally.

A tracked machine, sitting on steel tracks, could have the grease in the

tracks burst into flame. A wheeled

loader will have smoke coming from the tires as they begin to melt. Both situations call for fast action.

Disengage the machine from the wires, look around for other

hazards, and back away. If the machine's

arms are tangled, remember the rig has enough power to break the wires, but you

have to make sure you back clear, wherever they land. That is absolutely vital. Wires may be dark, and hard to see against

downed trees or a dark roadway. It's

essential that you back at least twenty feet away from them before exiting the

cab. If the ground is wet, back farther.

If for some reason you cannot back away, remain in the cab

and use a cell phone or radio to call for help.

When seeking help, the only thing someone can do is cut the power

remotely. Any attempts to approach your

energized machine will be lethal to potential rescuers. It's far better and safer to get your

machine out of danger under its own power.

Hopefully, you will never encounter powerlines in a

construction machine. If you do, just

remember. Stay inside. Keep your head. Disengage and back clear.

Once clear, flag the area as dangerous from a safe

distance. When walking near downed wires

it's possible to step from an area with no charge to a lethally charged area with

no visible indication of what is about to happen. In that sense, downed lines are more

dangerous than the deadliest snake, because they do not even have to touch you

to kill you.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on November 08, 2011 04:15

October 21, 2011

Night

Last night it happened again. Three in the morning I was awakened by the

screams. It sounded like they went on

for hours, but in reality they probably trailed off after a few minutes. This time, I stayed indoors, and I kept back

from the windows.

I've never heard of them smashing windows to break into an

unoccupied home, but they can certainly jump through glass if they see you

behind it. And an open window is just an

invitation.

Once they get inside, you have a real problem. Sharp teeth in a small space makes for a bad

time. I have a knife if it comes to

that.

Of course, windows on the second floor are safe, most of the

time. Very few can leap that high. But if one does . . . Better safe than sorry.

There's eight round of double-o buckshot in the gun, but I'm

worried that might not be enough, if they swarmed in together. I'm thinking of ringing the house with

lights, and setting up a position on the roof.

A fellow could get up there with

a rifle and an infrared sight, and pick them off in safety. Unless the birds get in on it too. Now that's a scary thought.

This morning there was nothing to be seen but a large patch

of blood and some hair, in the meadow between the house and the road. No telling what they got. That half a shoe we found the other day is

still unsettling. And it's going on

three weeks since that kid vanished.

Snake wants to rig claymore mines around the edges of the

lawn. I'm afraid of claymores, but it

may come to that. We'll see.

Meanwhile, darkness has fallen again, and I'm settled in for

another long night. I hope the night

vision I ordered arrives soon.

These posts get shorter and shorter because I don't want to run the lights to write at night. Anything I can see by, makes me visible to them. And that's bad. The electric power's been spotty too, and I'm wary of venturing outside to start the generator. Better rely on the batteries, and wait for dawn.

Maybe we should have rigged those claymores.

Tomorrow.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on October 21, 2011 19:24