Corey Robin's Blog, page 16

May 22, 2023

A Watergate for Our Time

If you haven’t caught an episode of “White House Plumbers,” the new HBO series on Watergate, I highly recommend it.

For people my age, Watergate will always be connected to All the President’s Men, not the book by Woodward and Bernstein but Alan J. Pakula’s 1976 film. I can’t think of Ben Bradlee without thinking of Jason Robards, Deepthroat without Hal Holbrook, or Hugh Sloan without Meredith Baxter Bierney, who played Sloan’s wife in the film.

The point of the film, and those actors, was to supply a sense of gravitas to a country stricken by the sordidness of the affair. No matter how criminal Nixon may have been, his criminality was redeemed by the feel of the film, with its spirit of agonized conscience and liberal reckoning. That feel derived from the piety and passion of the Cold War, making it the perfect film for, and of, the Cold War state.*

We no longer live in the shadow of the Cold War. We no longer live in the shadow of 9/11. Both of those moments elicited a sense that something had to be done, that something could be done. We no longer live in those countries. We live in a country that exudes a sense that nothing can be done. Debt ceiling crisis? The Supreme Court will say no. Diane Feinstein’s refusing to retire and gumming up the works of judicial appointments? It’s her choice. Climate change? What are you going to do?

White House Plumbers is the story of Watergate told from the perspective of our own failed state. The series isn’t the story one attempted break-in at the Watergate hotel; it’s the story of four bungled attempts at a break-in. Gordon Liddy is no longer a scary ideological fanatic, as he was in All the President’s Men, burning his hand over a candle to prove how tough and committed he was. He’s now a dorky bumbler whose hand over the candle trick grosses out the prostitutes he’s trying to impress. Howard Hunt frets over country clubs and career. Both men come off as wannabe entrepreneurs who pitch the break-in at the hotel as if they were making bids for a contract with an aging nonprofit.

White House Plumbers is the story of a country whose time is past, of geriatric grifters who talk tough and trip over their shoelaces. It’s the Watergate for our time, the Watergate that forces us to see ourselves for who we are.

* My daughter, with whom I’ve been watching “White House Plumbers,” found this 1973 article in the New York Times by R.W. Apple, the dean of the White House press corps, about H.R. Haldeman, Nixon’s Chief of Staff. Headlined “Haldeman the fierce, Haldeman the faithful, Haldeman the fallen,” the article said, “Haldeman made himself into a latter‐day Janus, a guardian of the gateway to President Richard M. Nixon, a god of the going and the coming.” That gives you a sense of the exalted terms in which this extended experiment in criminality was described by the Washington media.

April 22, 2023

Talking Clarence Thomas and Money with NPR’s Brooke Gladstone

I talked about the Clarence Thomas scandal with Brooke Gladstone on On the Media this weekend. You should be able to hear it on any NPR outlet wherever you are, but in case you miss it, here’s a link where you can catch it.

April 18, 2023

The real problem of Clarence Thomas

I’ve got a piece up at Politico this morning, setting out what I think the real Clarence Thomas scandal is, why corruption may not be the best way to think about it, and what the proper approach of the Left should be to the problem of Clarence Thomas:

As a description of the problem of Clarence Thomas, however, corruption too has its limits. Morally, corruption rotates on the same axis as sincerity — forever testing the purity or impurity, the tainted genealogy, of someone’s beliefs. But money hasn’t paved the way to Thomas’ positions. On the contrary, Thomas’ positions have paved the way for money. A close look at his jurisprudence makes clear that Thomas is openly, proudly committed to helping people like Crow use their wealth to exercise power. That’s not just the problem of Clarence Thomas. It’s the problem of the court and contemporary America….

Money “is a kind of poetry,” wrote Wallace Stevens. Thomas agrees. More than an aid to speech or speech in the metaphorical sense, money is speech. Not only do our donations to campaigns and candidates “generate essential political speech,” Thomas writes in a 2000 dissent, but we also “speak through contributions” to those campaigns and candidates. He’s not wrong. When my wife and I gave money to the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, we were doing more than aiding their candidacies. We were voicing our political values and advocating our policy preferences, just as we did when we showed up at their rallies and canvassed for them, door to door…

If money is speech, the implication for democracy is clear. There can be no democracy in the political sphere unless there is equality in the economic sphere. That is the real lesson of Clarence Thomas.

You can read the whole piece here, at Politico. And then, if you haven’t yet bought The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, which forms the basis for the piece, buy the book!

Update: I spoke with Forbes Magazine about the Clarence Thomas story. The interviewer is Diane Brady, who wrote one of the best books on Thomas, actually a group biography of Thomas and his Black classmates at Holy Cross. It was a delight to talk with her.

April 13, 2023

The real culture war between the left and the right is about money: On the Clarence Thomas scandal

Briahna Joy Gray, who is one of my favorite podcasters and interviewers, and I went deep into the Clarence Thomas scandal. I trace his actions back to an obscure speech he delivered to a libertarian outfit in San Francisco in 1987, where he set out his basic agenda and philosophy: “The real culture between the left and the right is about money.”

You can watch it here on YouTube.

March 29, 2023

Talking fascism, the Constitution, and history with Jamelle Bouie

Last week, as I was losing my voice, I had a really fascinating conversation with Jamelle Bouie of the New York Times, moderated by Katrina vanden Heuvel of The Nation, about the state of American democracy. You can watch it here. It was a wide-ranging discussion: we talked about whether fascism is a good model for understanding the contemporary American right, the helps and hindrances of the Constitution, the virtues and vices of returning to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for insights into current events, and more. Bouie is one of those rare political writers who really knows his history; it’s almost never that I read one of his Times columns without learning something I didn’t know about the American past. I strongly encourage you to read his work at the Times, and enjoy watching this video of our conversation. And apologies for my voice: my wife said I sounded like Brenda Vaccaro.

March 9, 2023

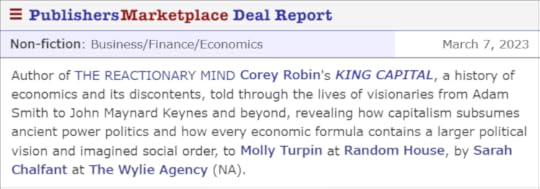

King Capital

I’ve been wanting to shout this from the rooftops, and now I can. I’ve just signed a contract for my next book, which is called King Capital, with Random House, where I’ll be working with Molly Turpin, who edited one of my favorite books of the last decade. After floundering around for a few years, with one false start after another, I’m thrilled to be writing this book and working with Molly. I feel more than lucky that Sarah Chalfant (The Wylie Agency), who did so much for this shidduch, is my agent.

Now to write the book. In the meantime here’s a brief article on the sale, which was reported in yesterday’s Publishers Marketplace.

December 4, 2022

Jane Austen on the Post Office and State Capacity

“The post-office is a wonderful establishment!” said she.—”The regularity and dispatch of it! If one thinks of all that it has to do, and all that it does so well, it is really astonishing!”

“It is certainly very well regulated.”

“So seldom that any negligence or blunder appears! So seldom that a letter among the thousands that are constantly passing about the kingdom, is even carried wrong—and not one in a million, I supposed, actually lost! And when one considers the variety of hands, and of bad hands too, that are to be deciphered, it increases the wonder!

“The clerks grow expert from habit.—They must begin with some quickness of sight and hand, and exercise improves them. If you want any further explanation,” continued he, smiling, “they are paid for it. That is the key to a great deal of capacity. The public pays and must be served well.”

—Jane Fairfax talking with John Knightley in Emma

December 1, 2022

Bloomsbury Bolsheviki and other topics

Long-time followers of this blog know that I’ve been promising, for several years, a piece on Smith and a piece on Keynes. I’m happy to say that they are finally out in successive issues of the New York Review of Books. The editors there were extremely generous with space, allowing me, across two consecutive issues and some 13,000 words, to write what has become a two-part article about these two economists.

Looking over my notes, I see that my first note to myself about the piece I had hoped to write was in February 2020. So it’s taken me a really long time! But it was time well spent. Not only did I love digging into these two thinkers, but I’ve come up, finally, with the next book project. I’ll have more to say about that later, but the basic idea is to re-read all the great economists as political thinkers, to understand the modern economy as the equivalent of what the polis was in ancient Greece or the church was in medieval Europe: the primary space of our collective being.

Here is the Smith piece:

It’s no accident that Adam Smith was the first great economist as well as our most acute psychologist of the enlarged form of “fellow feeling” that went, in the eighteenth century, by the name of sympathy. Once upon a time, economics and sympathy were one and the same. Yet something got lost on the way to the market. Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) opens with pleasant stories of workers cooperating in a pin factory and quick-witted boys scrambling over steam engines, inventing labor-saving devices for pistons and boilers, so they can leave the machines unattended and rush off to play with their mates. It closes with scenes of stunted and stupefied laborers, colonial slavers, premonitions of violent revolt from indigenous peoples dispossessed of their lands, and a monstrous and modern form of sovereignty called the East India Company. Sympathy is nowhere to be found; profit occludes all.

If one terminus of commercial society was the blinding of the self to the other, a second was the engulfment of the self by the other. An isolate on a desert island, Smith observes, thinks clearly about the contribution of material goods to his enjoyment and ease. Lacking the mirror of society, in which a bauble is reflected back to us as a useful good, the castaway is less likely to forsake the convenience of a toothpick or a nail clipper for the prize of wealth. Only in society do riches take on value and become an object of our labors—not because they bring us greater material satisfaction but because “they more effectually gratify that love of distinction so natural to man.”

That pendulum swing, between the pathologies of insufficient and excessive feeling for the other, haunts modern economics. Too little feeling gives rise to dispossession. Too much feeling warps the self’s relationship to material goods. Smith and John Maynard Keynes are the great theorists of this dynamic. Karl Marx, W.E.B. Du Bois, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Thorstein Veblen wrote about it, too. But Smith and Keynes are unique. Conscious of the pathologies of sympathy, they still retain the ideal of the market as a sphere of sociability. That lends their work a special poignancy today, when we are again asking the question that once agitated so many: What is the purpose of the economy, and to what extent does it reflect our social selves?

And here is the Keynes piece:

Much of Keynes’s economics, like Smith’s, is a sustained exercise in empathy-building, attempting to create on paper the solidarity that has failed to materialize in practice. But where Smith thought there were forms of self-interested, profit-driven action that would gradually orient the self to the other, Keynes could not take that orientation for granted. In “modern conditions,” he wrote, the individualism of the Smithian economy was at best no longer applicable and at worst a “mortal disease.” A path that works for me when I take it alone may work against me if everyone takes it, too. The modern economy is littered with examples of this, yet knowledge of the social dimension of economic action—that we do not choose alone, that our actions have effects on others—has not yet penetrated our decisions in the market. The task of the economist is to create the social knowledge of the other that Smith hoped would arise from the act of seeking profit for oneself.

…

In politics, Walter Benjamin wrote, “it is not private thinking but…the art of thinking in other people’s heads that is decisive.” The power of Keynes’s economics is that it assigns that art of public thinking not to the statesman or citizen but to the economist and to ordinary economic actors. This was increasingly true of Keynes’s work throughout the 1920s and 1930s, culminating in the climactic passages in The General Theory where he addresses the relationship between saving and spending, investment and enterprise.

Last, if you’re still up for more writing, I did a lovely interview with the New Book Network, which can be found here. Some highlights:

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: None of them. With one exception, every writer whom I respect and admire that I’ve met has been a letdown. On the page, they’re curious and captivating. In person, they’re awkward, I’m awkward. It’s draining. I only want to know them through their writing.

…

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

A: Whenever people answer this question, they talk about the books that had a positive impact on them, that they’ve internalized and made their own. I find that answer suspicious.

The books that had the greatest impact are those we loved as students—and have spent our lives trying to get away from. At some point, we came to think that these books are in error and that we were in error for loving them. There’s something discomfiting, morally discomfiting, about our being so besotted with those books; it seems like a deficiency of character. We try to get as far away from them as we can. It’s like a relationship you had when you were younger that you’d like to think you’ve outgrown. But, of course, we haven’t outgrown those books because we spend our lives running away from them, working through our attraction to them.

For me, that book is, hands down,…

…

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to students and why?

A: I love texts that are challenging enough to require interpretive footwork but not so abstruse that I do all that footwork for the students. I used to love teaching Marx’s Capital, but it requires so much advance layering on my part, that the energy of collective discovery, where students and I figure out the text together, is lost. If students aren’t involved in the collective work of interpretation, it’s not the classroom experience I want them to have.

Here are some books where that doesn’t happen.

Thanks for reading, and hope everyone is doing well and is healthy.

November 28, 2022

Slavery and Capitalism, Neoliberalism and Feudalism

Next semester, I’ll be teaching American Political Theory (POLS 3404), meeting 9:30-10:45 on Mondays and Wednesdays. We’ll focus on two topics only: slavery and neoliberalism. Registration is now officially open for the class.

During the first half of the course, we’ll be addressing the relationship between slavery and capitalism through a selection of primary and second readings. Our texts will include Orlando Patterson’s Slavery and Social Death, Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery, Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism, Eugene Genovese’s The Political Economy of Slavery, Frederick Douglass’ Narrative, Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction, and various texts and treatises from the slaveholders, including Thomas Dew, William Harper, James Henry Hammond, Josiah Nott, and John C. Calhoun.

In the second half of the course, we’ll be addressing the relationship between neoliberalism and feudalism, also through a selection of primary and secondary readings. Our texts will include readings from Friedrich Hayek, Gary Becker, Milton Friedman, Ayn Rand, James Buchanan, Melinda Cooper, Elizabeth Anderson, Wendy Brown, Jodi Dean, Silvia Federici, and Nancy Fraser.

The course will be framed by some introductory readings from Marx, Weber, and Ellen Meikens Wood. As the pairings of capitalism and slavery, and neoliberalism and feudalism, suggest, we’ll be using American political thought as a prism through which we examine whether and how different kinds of social and economic institutions, drawn from different moments in time, can coexist and reinforce each other at the same time.

August 9, 2022

From Aeschylus to Alison Bechdel

This fall, I’m teaching an undergraduate seminar, “Politics Through Literature,” at Brooklyn College. Space is still open.

Our syllabus runs from Aeschylus to Alison Bechdel, concentrating on the politics of the family, beauty, money, and sex. Along the way, we’ll read Vivian Gornick, Ralph Ellison, Bertolt Brecht, Plato, Marx, James Baldwin, Anton Chekhov, Barbara Fields, Euripides, Edward P. Jones, Jane Austen, Nietzsche, Wollstonecraft, Adam Smith, Franz Kafka, Toni Morrison, and more.

If you’re looking for a three-credit class on Monday and Wednesday mornings, from 11 to 12:15, feel free to reach out to me ([email protected]) or sign up for POLS 3440.

Feel free to share this post with any and all CUNY students or students who want to sign up for a class at Brooklyn College.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 155 followers