Corey Robin's Blog, page 20

April 17, 2019

David Brion Davis, 1927-2019: Countersubversive at Yale

David Brion Davis, the pathbreaking Yale historian of slavery and emancipation, whose books revolutionized how we approach the American experience, has died. The obituaries have rightly discussed his many and manifold contributions, a legacy we will be parsing in the days and months ahead. Yet for those of us who were graduate students at Yale during the 1990s and who participated in the union drive there, the story of David Brion Davis is more complicated. Davis helped break the grade strike of 1995, in a manner so personal and peculiar, yet simultaneously emblematic, as not to be forgotten. Not long after the strike, I wrote at length about Davis’s actions in an essay called “Blacklisted and Blue: On Theory and Practice at Yale,” which later appeared in an anthology that was published in 2003. I’m excerpting the relevant part the essay below, but you can read it all of it here [pdf].

* * *

As soon as the graduate students voted to strike, the administration leaped to action, threatening students with blacklisting, loss of employment, and worse. Almost as quickly, the national academic community rallied to the union’s cause. A group of influential law professors at Harvard and elsewhere issued a statement condemning the “Administration’s invitation to individual professors to terrorize their advisees.” They warned the faculty that their actions would “teach a lesson of subservience to illegitimate authority that is the antithesis of what institutions like Yale purport to stand for.”

Eric Foner, a leading American historian at Columbia, spoke out against the administration’s measures in a personal letter to President Levin. “As a longtime friend of Yale,” Foner began, “I am extremely distressed by the impasse that seems to have developed between the administration and the graduate teaching assistants.” Of particular concern, he noted, was the “developing atmosphere of anger and fear” at Yale, “sparked by threats of reprisal directed against teaching assistants.” He then concluded:

I wonder if you are fully aware of the damage this dispute is doing to Yale’s reputation as a citadel of academic freedom and educational leadership. Surely, a university is more than a business corporation and ought to adopt a more enlightened approach to dealing with its employees than is currently the norm in the business world. And in an era when Israelis and Palestinians, Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Serbs, the British government and the IRA, have found it possible to engage in fruitful discussions after years of intransigent refusal to negotiate, it is difficult to understand why Yale’s administration cannot meet with representatives of the teaching assistants.

Foner’s letter played a critical role during the grad strike. The faculty took him seriously; his books on the Civil War and Reconstruction are required reading at Yale. But more important, Foner is a historian, and at the time, a particularly tense confrontation in the Yale history department was spinning out of control.

The incident involved teaching assistant Diana Paton, a British graduate student who was poised to write a dissertation on the transition in Jamaica from slavery to free labor, and historian David Brion Davis. A renowned scholar of slavery, Davis has written pathbreaking studies, earning him the Pulitzer Prize and a much-coveted slot as a frequent writer at the New York Review of Books. He represents the best traditions of humanistic learning, bringing to his work a moral sensitivity that few academics possess. Paton was his student and, that fall, his TA.

When Paton informed Davis that she intended to strike, he accused her of betraying him. Convinced that Davis would not support her academic career in the future—he had told her in an unrelated discussion a few weeks prior that he would never give his professional backing to any student who he believed had betrayed him—Paton nevertheless stood her ground. Davis reported her to the graduate school dean for disciplinary action and had his secretary instruct Paton not to appear at the final exam. In his letter to the dean, Davis wrote that Paton’s actions were “outrageous, irresponsible to the students…and totally disloyal.”

The day of the final, Paton showed up at the exam room. As she explains it, she wanted to demonstrate to Davis that she would not be intimidated by him, that she would not obey his orders. Davis, meanwhile, had learned of Paton’s plan to attend the exam and somehow concluded that she intended to steal the exams. So he had the door locked and two security guards stand beside it.

Though assertive, Paton is soft-spoken and reserved. She is also small. The thought of her rushing into the exam room, scooping up her students’ papers, engaging perhaps in a physical tussle with the delicate Davis, and then racing out the door—the whole idea is absurd. Yet Davis clearly believed it wasn’t absurd. What’s more, he convinced the administration that it wasn’t absurd, for it was the administration that had dispatched the security detail.

How this scenario could have been dreamed up by a historian with the nation’s most prestigious literary prizes under his belt—and with the full backing of one of the most renowned universities in the world—requires some explanation. Oddly enough, it is Davis himself who provides it.

Like something out of Hansel and Gretel, Davis left a set of clues, going back some forty years, to his paranoid behavior during the grade strike. In a pioneering 1960 article in the Mississippi Valley Historical Review, “Some Themes of Counter-Subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti-Catholic, and Anti-Mormon Literature,” Davis set out to understand how dominant groups in nineteenth-century America were gripped by fears of disloyalty, treachery, subversion, and betrayal. Many Americans feared Catholics, Freemasons, and Mormons because, it was believed, they belonged to “a machine-like organization” that sought “to abolish free society” and “to overthrow divine principles of law and justice.” Members of these groups were dangerous because they professed an “unconditional loyalty to an autonomous body” like the pope. They took their marching orders from afar, and so were untrustworthy, duplicitous, and dangerous.

Davis was clearly disturbed by the authoritarian logic of the countersubversive, but that was in 1960 and he was writing about the nineteenth century. In 1995, confronting the rebellion of his own student, the logic made all the sense in the world. It didn’t matter that Paton was a longtime student of his, that she had many discussions with Davis about her academic work, and that he knew her well. As soon as she announced her commitment to the union’s course of action, she became a stranger, an alien marching on behalf of a foreign power.

Davis was hardly alone in voicing these concerns. Other respected members of the Yale faculty dipped into the same well of historical imagery. In January 1996, at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, several historians presented a motion to censure Yale for its retaliation against the striking TAs. During the debate on the motion, Nancy Cott—one of the foremost scholars of women’s history in the country who was on the Yale faculty at the time but has since gone on to Harvard—defended the administration, pointing out that the TA union was affiliated with the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union. Historians at the meeting say that Cott placed a special emphasis on the word “international.” The TAs, in other words, were carrying out the orders of union bosses in Washington. The graduate students did not care about their own colleagues, they were not loyal to their own. Not unlike the Masons and Catholics of old. It did not seem to faze Cott that she was speaking to an audience filled with labor historians, all of whom would have recognized these charges as classic antiunion rhetoric.

One of the reasons Cott embraced this vocabulary so unselfconsicously was that it was a virtual commonplace among the Yale faculty at the time. At a mid-December faculty meeting, which one professor compared to a Nuremberg rally, President Levin warned the faculty of the ties between the TAs and outside unions. The meeting was rife with lurid images of union heavies dictating how the faculty should run their classrooms. It never seemed to occur to these professors, who pride themselves on their independent judgment and intellectual perspicacity, that they were uncritically accepting some of the ugliest and most unfounded prejudices about unions, that they sounded more like the Jay Goulds and Andrew Carnegies of the late nineteenth century than the careful scholars and skeptical minds of the late twentieth. All they knew was their fear—that a conspiracy was afoot, that they were being forced to cede their authority to disagreeable powers outside of Yale.

Cott, Levin, and the rest of the faculty were also in the grip of a raging class anxiety, which English professor Annabel Patterson spelled out in a letter to the Modern Language Association. The TA union, Patterson wrote, “has always been a wing of Locals 34 and 35 [two other campus unions]…who draw their membership from the dining workers in colleges and other support staff.”

Why did Patterson single out cafeteria employees in her description of Locals 34 and 35? After all, these unions represent thousands of white- and blue-collar workers, everyone from skilled electricians and carpenters to research laboratory technicians, copy editors, and graphic designers. Perhaps it was that Patterson viewed dishwashers and plastic-gloved servers of institutional food as the most distasteful sector of the Yale workforce. Perhaps she thought that her audience would agree with her, and that a subtle appeal to their delicate, presumably shared, sensibilities would be enough to convince other professors that the TA union ought to be denied a role in the university.

The professor-student relationship was the critical link in a chain designed to keep dirty people out. What if the TAs and their friends in the dining halls decided that professors should wash the dishes and plumbers should teach the classes? Hadn’t that happened during the Cultural Revolution? Hadn’t the faculty themselves imagined such delightful utopias as young student radicals during the 1960s? Recognizing the TA union would only open Yale to a rougher, less refined element, and every professor, even the most liberal, had something at stake in keeping that element out.

In his article, Davis concluded with these sentences about the nineteenth-century countersubversive:

By focusing his attention on the imaginary threat of a secret conspiracy, he found an outlet for many irrational impulses, yet professed his loyalty to the ideals of equal rights and government by law. He paid lip service to the doctrine of laissez-faire individualism, but preached selfless dedication to a transcendent cause. The imposing threat of subversion justified a group loyalty and subordination of the individual that would otherwise have been unacceptable. In a rootless environment shaken by bewildering social change the nativist found unity and meaning by conspiring against imaginary conspiracies.

Though I don’t think Davis’s psychologizing holds much promise for understanding the Yale faculty’s response to the grade strike—the strike, after all, did pose a real threat to the faculty’s intuitions about both the place of graduate students in the university and the obligation of teachers; nor did the faculty seem, at least to me, to be on a desperate quest for meaning—he did manage to capture, long before the fact, the faculty’s fear that their tiered world of privileges and orders, so critical to the enterprise of civilization, was under assault. So did Davis envision the grotesque sense of fellowship that the faculty would derive from attacking their own students.

The faculty’s outsized rhetoric of loyalty and disloyalty, of intimacy (Dean [Richard] Brodhead called the parties to the conflict a “dysfunctional family”) betrayed, may have fit uneasily with their avowed professions of individualism and intellectual independence. But it did give them the opportunity to enjoy, at least for a moment, that strange euphoria—the thrilling release from dull routine, the delightful, newfound solidarity with fellow elites—that every reactionary from Edmund Burke to Augusto Pinochet has experienced upon confronting an organized challenge from below.

Paton’s relationship with Davis was ended. Luckily, she was able to find another advisor at Yale, Emilia Viotti da Costa, a Latin American historian who was also an expert on slavery. Da Costa, it turns out, had been a supporter of the student movement in Brazil some thirty years before and was persecuted by the military there. Forced to flee the country, she found in Yale a welcome refuge from repression.

March 26, 2019

Neoliberal Catastrophism

According to The Washington Post:

Former president Barack Obama gently warned a group of freshman House Democrats Monday evening about the costs associated with some liberal ideas popular in their ranks, encouraging members to look at price tags, according to people in the room.

Obama didn’t name specific policies. And to be sure, he encouraged the lawmakers — about half-dozen of whom worked in his own administration — to continue to pursue “bold” ideas as they shaped legislation during their first year in the House.

But some people in the room took his words as a cautionary note about Medicare-for-all and the Green New Deal, two liberal ideas popularized by a few of the more famous House freshmen, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.).

…

“He said we [as Democrats] shouldn’t be afraid of big, bold ideas — but also need to think in the nitty-gritty about how those big, bold ideas will work and how you pay for them,” said one person summarizing the former president’s remarks.

Obama’s words — rare advice from a leader who has shunned the spotlight since leaving office — come as the Democratic Party grapples with questions of how far left to lean in the run-up to 2020. Most Democratic candidates seeking the presidential nomination have embraced a single-payer health-care system and the Green New Deal, an ambitious plan to make the U.S. economy energy efficient in a decade.

It seems like there are an increasing number of areas where the discourse among centrists and liberals follows a fairly similar script. The opening statement is one of unbridled catastrophe: Trump is fascism on the ascendant march! Global warming will destroy us in the next x years! (I’m not making any judgments here about the truth of these claims, though for the record, I believe the second but not the first). The comes the followup statement, always curiously anodyne and small: Let’s nominate Klobuchar. How are you going to pay for a Green New Deal? Don’t alienate the moderates.

All of these specific moves can be rationalized or explained by reference to local factors and considerations, but they seem like part of a pattern, representing something bigger. Perhaps I’ve been reading too much Eric Hobsbawm for a piece I’m working on, but the pattern seems to reflect the reality of life after the Cold War, the end of any viable socialist alternative. For the last quarter-century, we’ve lived in a world, on the left, where the vision of catastrophe is strong, while the answering vision remains inevitably small: baby steps, cap and trade, pay as you go, and so on. Each of these moves might have its own practical justifications, but it’s hard to see how anyone could credibly conjure from those minuscule proposals a blueprint that could in any way be commensurate with the scale of the problem that’s just been mooted, whether it be Trump or climate change.

I wonder if there is any precedent for this in history. You’ve had ages of catastrophe before, where politicians and intellectuals imagined the deluge and either felt helpless before it or responded with the most cataclysmic and outlandish utopias or dystopias of their own. What seems different today is how the imagination of catastrophe is coupled with this bizarre confidence in moderation and perverse belief in the margin.

Neoliberal catastrophism?

March 25, 2019

Thoughts on Russiagate, Mueller, and Trump’s Prospects for Reelection

I find myself in a peculiar position with regard to the Mueller report (assuming—big assumption, I know—that we have a good enough sense at this point of what’s in it).

On the one hand, I was part of the Russiagate skeptic circle. I didn’t doubt that Russia had attempted to influence the election, but I didn’t think that attempt had much if any consequence; those who did, I thought, were grasping at straws. Nor did I think there was a strong case for the claim that Trump actively colluded with that effort and had thus put himself and the United States in hock to Putin. The evidence of all the active anti-Russian measures on the part of the US since Trump was elected was simply too great to lend those arguments too much credence. I also never believed, whatever the outcome of the report, that it would be the downfall of Trump or lead to his impeachment. I always took Nancy Pelosi at her word when she said, long before the midterms, that there would be no impeachment.

And like the other Russiagate skeptics, I found the constant breathless commentary, where each revelation was going to lead to the final end, where Trump was called a Russian asset (Lindsey Graham, too) grating in the extreme. And since I thought the attacks on the skeptics were nasty and often unfair, I can certainly understand why they’re now crowing; had I been as out in front or outspoken as they, I would be crowing, too.

But the bottom line is that I don’t feel disappointed or surprised by the outcome of the report—again, assuming (big assumption) we have a decent enough sense at this point of what is in the report—because I had fairly low expectations of it going in. If anything I feel relief that it’s over.

I always insisted that the investigation should proceed (and thought the fear that it was going to be shut down prematurely to be vastly overblown) and that it was good that it was happening because there was clearly enough evidence of impropriety and illegality for it to go forward. I thought it was good to get to the bottom of things, and the evidence of corruption that it has turned up seems like, maybe, a useful roadmap going forward for thinking about political power and oligarchy. And as others have pointed out, it shows the double standards of our justice system, where the poor are punished and the rich and powerful get off fairly easily. But I always thought the vision of Trump humiliated by Mueller and then impeachment were, like the idea of Putin’s puppet or a stolen election, completely fanciful.

On the other hand, unlike many in the Russiagate skeptic circle, I don’t think the Mueller report really changes much of anything in terms of the political situation we’re in. I don’t think Trump is going to get some big boost from this, as a lot of lefties seem to think. The fact is, the Democrats, on the ground, have been—very wisely, I might add—focusing on the economy, voting rights, racism and anti-immigrant nativism. They have not been pushing Russia as an electoral question. This has always been a media and social media obsession; for once in their lives, most Democrats, on the ground, have made the rational political calculation.

So where does that leave us? Pretty much where we’ve always been. If you hoped Mueller and Russia would be the downfall of Trump and are now crestfallen, I’d say you really have no reason to feel upset. What will bring Trump down will be what was always going to bring down Trump: his failure to deliver enough to the party’s voters, the growing incoherence and unsettlement on the right about what its basic project is all about, and the rising organization of the left.

So it’s back to our regularly scheduled programming. Hopefully, with less distraction and fewer fantasies of happy endings.

March 4, 2019

Do You Believe in Life After Hayek

Sorry about the title; advertisements for The Cher Show are all over New York these days, so the song is in my head. Anyway…

In the Boston Review, the left economists Suresh Naidu, Dani Rodrick, and Gabriel Zucman offer an excellent manifesto of sorts for a new progressive economic agenda. I was asked to respond, and in a move that surprised me, I wound up returning to Hayek to see what we on the left might learn from him and his achievement. Here’s a snippet:

Far from resting neoliberalism on the authority of the natural sciences or mathematics (forms of inquiry Hayek and Mises sought to distance their work from) or on the technical knowledge of economists (as Naidu and his co-authors claim), Hayek recognized that the argument for capitalism had to be won on moral and political grounds through the political arts of persuasion.

Here’s where things get interesting. Though Hayek famously abandoned formal economics for social theory after the 1930s, his social theory remained dedicated to elaborating what he saw as the essential problem of economics: how to allocate finite resources between different purposes when society cannot agree on its most basic ends. With its emphasis on the irreconcilability of our moral ends—the fact that members of a modern society do not and cannot agree on a scale of values— Hayek’s point was fundamentally political, the sort of insight that has agitated everyone from Thomas Hobbes to John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas. Hayek was unique, however, in arguing that the political point was best addressed, indeed could only be addressed, in the realm of the economic. No other discourse—not moral philosophy, political theory, psychology, or theology—understood so well that our ultimate moral values and political purposes get expressed to others and revealed to ourselves only under conditions of radical economic constraint—when one is forced to assign a limited set of resources to different ends, ends that favor different sectors of society.

Morals are not really morals if they are not material, Hayek believed. Outside the constraining circumstance of the economy, our moral claims are so much wind. Inside the economy, they assume force and depth, achieving a revelatory clarity and profundity….

The intrinsic links between moral and economic life as well as the intractability of moral conflict, the incommensurability of our moral views, were the kernels of insight that animated Hayek’s most far-reaching writing against socialism. The socialist presumes an agreement on ultimate ends: the putatively shared understanding of principles such as justice or equality is supposed to make it possible for state planners to conceive of their task as technical, as the neutral application of an agreed upon rule. But no such agreement exists, Hayek insisted, and if it is presumed to exist, nothing will reveal its non-existence more quickly than the attempt to implement it in practice, in the distribution of finite resources toward whatever end has been agreed upon.

…

Hayek translated moral and political problems into an economic idiom. What we need now, I would argue, is a way to uninstall or reverse that translation.

In the rest of the piece, I briefly (very briefly) sketch out, with the help of Polanyi, what that might mean. This is something I hope to be developing further in an article I’m writing with Alex Gourevitch on socialist freedom. But in the meantime, here’s the Boston Review piece in full.

Marshall Steinbaum and Alice Evans also have excellent responses.

March 1, 2019

Interview about the Historovox with Bob Garfield of On the Media

My piece on the Historovox has provoked a lot of controversy and pushback. Dan Drezner devoted a column to it in The Washington Post. Others have weighed in on social media. I had a chance to talk with Bob Garfield of the NPR show On the Media about the piece. Have a listen.

February 28, 2019

I was the target of a private Israeli intelligence firm, and all I got was this lousy t-shirt

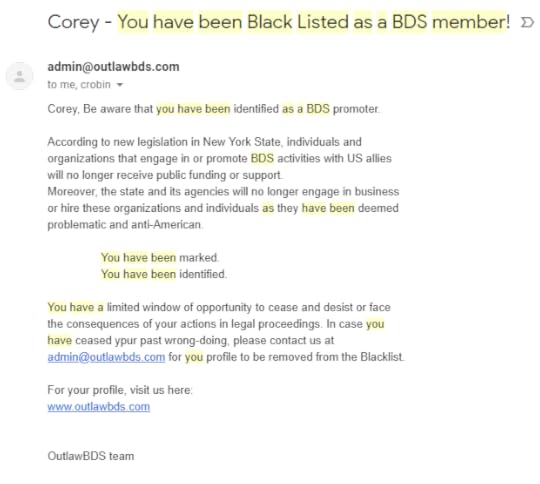

In September 2017, I got a “cease and desist” email from an organization called outlawbds. They informed me that because of my activism around BDS, I had been put on a “blacklist”—yes, they used that word, twice—and that I had a limited window of time to change my tune on BDS in order to get my name removed from the blacklist and avoid the legal consequences of my advocacy. “You have been marked,” the email warned me. “You have been identified.”

Turns out the whole thing was part of an operation of an Israeli intelligence firm called “Psy-Group.” Whose activities have now been exposed in The New Yorker.

Here are just a snippet of the items that might be of interest to those of us on CUNY campuses and in the New York area.

The campaign, code-named Project Butterfly, initially targeted B.D.S. activists on college campuses in “a single U.S. state,” which former Psy-Group employees have told me was New York. The company said that its operatives drew up lists of individuals and organizations to target. The operatives then gathered derogatory information on them from social media and the “deep” Web, areas of the Internet that are not indexed by search engines such as Google. In some cases, Psy-Group operatives conducted on-the-ground covert human-intelligence, or HUMINT, operations against their targets. Israeli intelligence officials insist that they do not spy on Americans, a claim that is disputed by their U.S. counterparts. Israeli officials said, however, that this prohibition does not apply to private companies such as Psy-Group, which use discharged Israel Defense Forces soldiers and former members of elite intelligence units, rather than active-duty members, in operations targeting Americans.

You can read more here.

And here’s the email I got.

February 20, 2019

The Historovox Complex

I’ve got a new gig at New York Magazine, where I’ll be a regular contributor, writing on politics and other matters. Here, in my first post, I tackle “the Historovox” (my wife Laura came up with the phrase), that complex of journalism and academic research that we increasingly see at places like Vox, FiveThirtyEight, and elsewhere. Long story, short: while I firmly believe in academics writing for the public sphere, there are better and worse ways to do it.

Here are some excerpts:

There’s a bad synergy at work in the Historovox — as I call this complex of scholars and journalists — between the short-termism of the news cycle and the longue durée-ism of the academy. Short-term interests and partisan concerns still drive reporting and commentary. But where the day’s news once would have been narrated as a series of events, the Historovox brings together those events in a pseudo-academic frame that treats them as symptoms of deeper patterns and long-term developments. Unconstrained by the protocols of academe or journalism, but drawing on the authority of the first for the sake of the second, the Historovox skims histories of the New Deal or rifles through abstracts of meta-analysis found in JSTOR to push whatever the latest line happens to be.

When academic knowledge is on tap for the media, the result is not a fusion of the best of academia and the best of journalism but the worst of both worlds. On the one hand, we get the whiplash of superficial commentary: For two years, America was on the verge of authoritarianism; now it’s not. On the other hand, we get the determinism that haunts so much academic knowledge. When the contingencies of a day’s news cycle are overlaid with the laws of social science or whatever ancient formation is trending in the precincts of academic historiography, the political world can come to seem more static than it is. Toss in the partisan agendas of the media and academia, and the effects are as dizzying as they are deadening: a news cycle that’s said to reflect the universal laws of the political universe where the laws of the political universe change with every news cycle.

…

The job of the scholar is not to offer her expertise to fit the needs of the pundit class. It’s to call those needs into question, not to provide different answers to the same questions but to raise the questions that aren’t being asked.

Everyone knows and cites Orwell’s famous adage: “To see what is front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” Less cited is what follows: “One thing that helps toward it is to keep a diary, or, at any rate, to keep some kind of record of one’s opinions about important events. Otherwise, when some particularly absurd belief is exploded by events, one may simply forget that one ever held it.” To see what’s right in front of one’s nose doesn’t mean seeing without ideology. It means keeping track of how we think and have thought about things, being mindful of what was once on the table and what has disappeared from view. It means avoiding the gods of the present.

The job of the scholar, in other words, is to resist the tyranny of the now. That requires something different than knowledge of the past; indeed, historians have proven all too useful to the Historovox, which is constantly looking for academic warrants to say what its denizens always and already believe. No, the job of the scholar is to recall and retrieve what the Marxist critic Walter Benjamin described as “every image of the past that is not recognized by the present.” The task is not to provide useful knowledge to the present; it is to insist on, to keep a record of, the most seemingly useless counter-knowledge from the past — for the sake of an as-yet-to-be imagined future.

The whole thing is here.

February 15, 2019

Adorno in America

The history of the Frankfurt School in America is usually told as a story of one-way traffic. The question being: What did America get from the Frankfurt School? The answer usually offered: a lot! We got Marcuse, Neumann, Lowenthal, Fromm, and, for a time, Horkheimer and Adorno (who ultimately went back to Germany after the war)—the whole array of émigré culture that helped transform the United States from a provincial outpost of arts and letters into a polyglot Parnassus of the world.

The wonderfully counter-intuitive and heterodox question that animates Eric Oberle’s Theodor Adorno and the Century of Negative Identity is: what did the Frankfurt School get from America? To the extent that question has been asked, it has traditionally provoked a negative response. Not a lot. Adorno was notoriously unhappy in the US: the kitsch, the kitsch. And for those Frankfurters who may have found what they were looking for in the States, the suspicion has always been that they were somehow seduced and made less smart—less gloomy, less dialectical, less mandarin, less mitteleuropäisch—by their experience in the US. Witness Erich Fromm.

But Oberle refuses that argument. In a work of boundless ambition and comparable achievement, which combines close reading of familiar texts and synoptic intellectual histories that bring together unfamiliar texts, The Century of Negative Identity shows just how indebted the Frankfurt School, particularly Adorno and Horkheimer, was to its time in America. One of the most innovative and exciting sections of the book (of which there are many) involves a re-reading of the relationship between The Authoritarian Personality and Dialectic of Enlightenment.

The two works are often taken as almost polar opposites: the first, a dutiful recitation of American-style social science, replete with data-sets and survey modules, and enough quantitative evidence to make a social psychologist swoon; the other, a recondite work of continental philosophy, with enough obscurity (of argument, style, organization, scope) to make a comp lit grad student swoon. The freshness of Oberle’s approach is to show how much the two works owe to each other. Deftly combining different facets and disciplinary invocations of identity—from logic and epistemology to social psychology and politics—Oberle demonstrates that Adorno consistently found himself reworking issues of identity through his efforts in The Authoritarian Personality, setting him up for his masterwork in postwar Germany, Negative Dialectics. Often presented as an unpleasant distraction from his philosophical work, Adorno’s work on The Authoritarian Personality was something Adorno actually enjoyed; as Oberle notes, Horkheimer reports in a November 1944 letter that Adorno said “that he ‘had a lot of fun’ meeting with the Berkeley Public Opinion group to develop preliminary questions on the ‘F-Scale.'”

Since the election of Trump, The Authoritarian Personality has been revived as a kind of Rosetta Stone to our age of authoritarianism. For good reason. In its time, the work was a path-breaking attempt to combine different methods in the social sciences (in-depth interviews, surveys, and so on), with an orientation that was both quantitative and qualitative, approaching questions of individual personality through a variety of lenses: politics, economics, psychology, and sociology. It was highly self-conscious about its methods, about the relationship between researcher and researched. More important, it asked the question of whether it was possible for a democratic seeming society to prove host to assorted anti-democratic tendencies. Understandably, a work of that sort would seem like a natural resource for our present moment.

But as Oberle shows, the actual approach of The Authoritarian Personality was light years away—and ahead!—of our current approaches. Too often today, the discussion around authoritarianism in the US devolves into a set of easy oppositions. There is a part of the country, the coasts, that is enlightened, tolerant, open to diversity, and opposed to racism and misogyny. Then there is the benighted part of the country—the proverbial white working class, who are thought to be located in the Upper Midwest, Appalachia, and the South—that is psychologically disposed to the opposite values: ignorance, fake news, racism, misogyny, nativism, and parochialism. It’s like a parody of the Enlightenment that Rousseau would rise up and roar against, where moral values and intellectual typologies become the markers of greater and lesser civilization.

The Authoritarian Personality, by contrast, was inspired by the dialectician’s belief in what Oberle calls, in a luminous phrase, “the shortest distance between norm and extreme.” Where much of the dominant social psychology of the time (and this would increase during the Cold War) set up a contrast between the normal, adaptive, humane, egalitarian ethos of democracy and the pathological, maladaptive, domineering ethos of authoritarianism, Adorno and his co-authors understood the world as one of contradiction, where the poles of disagreement or dissimilarity often masked or rested upon a deeper synthesis of agreement or similarity. The adaptive and maladaptive might simply be different expressions of a more structured diremption in a society or institution. As Horkheimer wrote to Adorno in a programmatic letter of 1945:

If in a family with two boys where the respected father or beloved mother complains repeatedly about having been cheated or outsmarted by Jews, one boy sticks to the general doctrines of good behavior and neighborly love advocated in school and home, and the other boy goes out and hits a Jew, who, do you think, acts more neurotically? I admit, the problem is not easy.

In their interviews and empirical research, the team behind The Authoritarian Personality consistently found cases of the tolerant and egalitarian enfolding more racist and anti-Semitic views. Rather than simply seeing the first as a mask for the second, however, the authors attempted to show how imbricated the two views were and how easily they could co-habit in the same mind.

Another distinctive feature of their research was their refusal to take group identities as pre-existent or natural. Adorno, Oberle argues, was haunted by the same question that haunted Simmel: “Why must the Stranger be hated?” All too often in contemporary discourse, there seems to be an assumption that there must always be in any group an Other. Adorno and his colleagues worked tirelessly to understand how groups are constructed as in-groups and out-groups, and how that process of construction so often preceded or transcended more psychological accounts of identity formation. As Oberle writes of The Authoritarian Personality:

The study went out of its way to avoid naturalizing identitarian logics. In conducting interviews, the interviewers were instructed to make no assumptions about outgroups—neither their membership, nor mutual antagonism, nor even their actual existence. Outgroups were analyzed as they existed in the minds of the interviewees…most individuals related to group collectivities first through the law and property relations, and then through a sense of shared vulnerability. Groups therefore formed not organically but as a network among similarly situated individuals. Therefore, though interviewers probed whether self- or ingroup concepts were formed antithetically, they were careful neither to suggest identitiarian thinking is necessarily neurotic, pathological, or aggressive, nor to cast notions of group antagonism as inevitable or natural. To do so would tribalize individuality.

As this passage suggests, The Authoritarian Personality took the materiality of identity and social and psychological life seriously. Identities are not given; they are made, through law, property, institutions, and the like. That, too, sets Adorno’s work off from much of the contemporary discourse of authoritarianism in America, which sees the source of the problem to be overwhelmingly psychological, strictly within the heads of individuals, something that can only be solved by better education.

The materialism of Adorno and his team leads Oberle to make a fascinating connection between The Authoritarian Personality and the Frankfurt School, on the one hand, and the great midcentury works of American social analysis such as Myrdal’s American Dilemma. This discussion opens an entire new window on the discourse of race and racism in America, with Adorno offering a counterpoint to the heavily psychological approach that so many writers took to what used to be called “race relations” in the United States. In an afterward to The Authoritarian Personality that was never published, Adorno wrote of Myrdal:

The gist of Aptheker’s argument is that the Negro problem is [in Myrdal] abstracted from its socio-economic conditions, and as soon as it is treated as being essentially of a psychological nature, its edge is taken away.

The Aptheker in question, of course, is Herbert Aptheker, the Marxist historian of slave revolts. That Adorno would find a sympathetic critic in Aptheker suggests not only how resolute he was in his effort to meld economics and psychology (“the concept that there is economy on the one hand, and individuals upon whom it works on the other, has to be overcome”) but also the connection he saw in the question of anti-Semitism and European fascism, on the one hand, and racism and American authoritarianism on the other. That connection has recently been taken up quite a bit in histories of the Nazis (most notably in the work of James Q. Whitman), but Oberle reveals a whole discourse in the 1940s that was very much concerned with the same problem. A discourse that got shut down during the Cold War, when the attention of the American state shifted from fighting fascism to fighting communism.

But while that discourse was live, it insisted, as Adorno did, not on sequestering the psychological, the way so many contemporary accounts of racism do, but on mixing the material and the psychological.

As Oberle shows, that discourse from the 1940s now reads almost like the lost tractates of an ancient civilization. And yet, as Oberle also shows, it still speaks to us, calling out what we have yet to learn. As Ralph Ellison put it in an unpublished review of An American Dilemma from 1941:

In our culture the problem of the irrational, that blind spot in our knowledge of society where Marx cries out for Freud and Freud for Marx, but where approaching, both grow wary and shout insults lest they actually meet, has taken the form of the Negro problem.

So it remains today, where discussions that attempt to relate the question of race to the organization of capitalism are dismissed and reduced to the mocking rubric of “economic anxiety.”

Update (8 pm)

As someone on Twitter pointed out, Ellison’s review, while it was not published by The New Republic, which had commissioned it, did appear in his collection of essays Shadow and Act.

On Facebook, Peter Gordon, who knows more about the Frankfurt School than just about anyone, says that my claim about the American connections of the Frankfurt School not being sufficiently studied is overstated if not wrong. He pointed me to this volume, which he says has been “unjustly neglected,” and which also looks excellent.

A State of Emergency or a State of Courts?

The Washington Post reports this morning, “If President Trump declares a national emergency to construct a wall on the southern border, only one thing is certain: There will be lawsuits. Lots of them. From California to Congress, the litigants will multiply.”

One of several elements of our time that I don’t think proponents of the authoritarianism or fascism thesis truly confront is just how much of Trump’s rule is mediated and ultimately decided upon by the courts.

Whenever Trump does something, everyone automatically assumes (and rightly so) that whether he can do it or not will be settled not by his violence or the alt-right’s strongman tactics or white supremacist masses in the streets but by an independent judiciary.

Now courts can be purely ornamental instruments of an authoritarian regime, that’s true. Judges can be terrorized into supporting a strongman or a fascist party. They can be bought off. Authoritarian rulers can fire or imprison or murder judges and simply replace them with toadies.

But that’s not what we have here. The judges who rule on Trump’s actions are both liberal and conservative; sometimes the former prevail, sometimes the latter. All of them have been duly appointed in accordance with a process (we can argue about Merrick Garland and Gorsuch, but there have been hundreds of judicial nominations or appointments under Trump that have been procedurally sound). However much their critics may not like their rulings, they are, for the most part, the standard judiciary you would see under a composite of Republican and Democratic presidents.

More important, as I said, we all of us in the United States, still assume that these judges and justices will have the last word on Trump’s rule. Not browbeaten or bribed judges and justices but independent judges and justices. Trump is not the decider of his own rule, in other words; the courts are.

For all the sense that Trump has transformed America, then, we still live in an America that looks remarkably like what Louis Hartz described in 1955: a country where “the largest issues of public policy should be put before nine Talmudic judges examining a single text.”

February 14, 2019

What does Trump’s pending declaration of emergency mean about his power and the state of his presidency?

What does Trump’s pending declaration of a state of emergency, so that he can commandeer funds to pay for his wall, mean politically? What does it tell us about his power or powerlessness?

I’ve talked on many occasions about Steve Skowronek’s theory of presidential power. In that account, presidential power is dependent on two factors: the strength and resilience of the existing regime, and the affiliation or orientation (supportive or opposed) of the president to that regime. The strongest presidents are those who come to power in opposition to an extraordinarily weak and tottering regime, who shatter that regime and construct a new one. Think Lincoln, FDR, and Reagan. The weakest presidents are those who are affiliated to a weak and tottering regime, and completely saddled with their affiliation to that regime. Think Herbert Hoover and Jimmy Carter.

There’s one part of Skowronek’s argument–a third factor, if you will–that I’ve not talked about. That is the organizational resources that a president has at his disposal. Where Skowronek’s theory of regimes and affiliations is cyclical–regimes rise and fall–the organizational element of his theory is linear. The organizational resources of the presidency grow over time. Early in the history of the American state, the material resources presidents had at their disposal were few; with time, they became many. Reagan had far more resources than Lincoln had or than Jefferson had, merely because of the expansion of the state apparatus itself.

One of the most fascinating twists in Skowronek’s argument is that the steady expansion of state power, the growth of material resources, works differently for different types of presidents.

For presidents who are in the strong or realignment position–Reagan, etc., back to Jefferson–there are more resources at their disposal over time. Reagan has more material power than Lincoln had. But there are also more resources available to state actors who would oppose these presidents. So Skowronek argues that if you compare Jefferson to Reagan, you’ll see that despite Reagan’s possession of greater material and organizational resources, Jefferson had far more political power and room for maneuver than Reagan did. Jefferson’s reconstruction of the political universe was far more comprehensive than Reagan’s–Reagan was never able to get rid of Social Security or Medicare, he tried to launch a new Cold War but wound up having to illegally fund the Contras because Congress would not allow him to do it legally, and so on–precisely because the state apparatus under Jefferson was not as strong as the one that was under Reagan. Which meant that Jefferson’s opponents had equally fewer resources to oppose him. Jefferson’s opponents, the Federalists, had the courts, and that was about it. And with time, and more judicial appointments, that went away, too.

But for presidents who are the in Carter/Hoover position–and this also includes John Adams and John Quincy Adams–the expansion of the state apparatus has the opposite effect. Though those presidents are in the weakest political position possible, over time, they are able to do more, despite their weakened position, precisely because there is so much more material and organizational power at their disposal. Yes, their opponents have power, too, but that power is not nearly as effective as the other kind of power their opponents have, namely, the political power that comes under a tottering regime.

So Carter, despite his very weak position, is able to do unbelievable things, things Jefferson (in a strong position) could only have dreamed of. Despite the tottering of the New Deal regime, there is still enough belief in government under Carter that he’s able to get two new Cabinet positions and departments (Energy and Education). He’s able to launch a military buildup. He’s able to deregulate whole industries. Most potent of all, he gets Paul Volcker at the Fed. John Adams and John Quincy Adams, who were in comparable positions, scrambled to do anything; Carter, despite being in the same position, is able to do a lot.

Now we come to Trump and his declaration of emergency.

From a political point of view, the situation looks like that of a classic weakened presidency. For two years, while his party had control over Congress, Trump got not a single dollar for building his wall. Amid the debacle of the shutdown (more on that in one second), it’s easy to forget that while Trump did manage to extract $1.375 billion from a Democratic-controlled House to build 55 new miles of wall, he could not even get that from a Republican-controlled Congress.

After his first two years in office, Trump played what he thought was his strongest suit: he provoked the longest government shutdown in American history hoping to finally get Congress to do what he had not yet been able to get it to do. Despite that power play, he came out with even less than he had going into the fight in December.

These are signs of classic presidential weakness. Remember, Trump staked his entire reputation on winning the midterms over the issue of immigration and the wall. His message heading into the November elections was as clear as it was crude: “If you don’t want America to be overrun by masses of illegal immigrants and massive caravans, you better vote Republican,” he said in a campaign speech. Well, the voters heard him, and cast their ballots accordingly, leading to the Democrats’ largest midterm gain since Watergate.

Losing big on a signature issue, not once, not twice, but three times–during the first two years when the Republicans controlled Congress; during the midterm elections; and then, with the shutdown–is a classic sign of what Skowronek calls presidential disjunction.

Like Carter, Trump is in a very weakened position. His ability to define the political field has been almost minimal.

Yet, like Carter, Trump is the beneficiary of the increased resources that are available to a president.

Over time, Congress has granted the presidency the power to declare national emergencies. Though the 1976 National Emergencies Act was meant to constrain the president, it hasn’t worked out that way. As Elizabeth Gotein of the Brennan Center writes in the current issue of The Atlantic:

Under this law, the president still has complete discretion to issue an emergency declaration—but he must specify in the declaration which powers he intends to use, issue public updates if he decides to invoke additional powers, and report to Congress on the government’s emergency-related expenditures every six months. The state of emergency expires after a year unless the president renews it, and the Senate and the House must meet every six months while the emergency is in effect “to consider a vote” on termination.

By any objective measure, the law has failed. Thirty states of emergency are in effect today—several times more than when the act was passed. Most have been renewed for years on end. And during the 40 years the law has been in place, Congress has not met even once, let alone every six months, to vote on whether to end them.

As a result, the president has access to emergency powers contained in 123 statutory provisions.

Trump is now pushing the presidency’s organizational resources, in the form of presidential emergencies, to their limit. Like Carter, he’s got resources at his disposal that John Adams did not have. But as was true of Carter, Trump’s dependence on those resources is not a sign of strength but weakness.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 155 followers