Brian Clegg's Blog, page 5

April 15, 2025

Mechanical Computation revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from April 2015It's of the nature of coincidences (that's another post) that your attention is drawn to something when it comes up several times in a short time span. I'm just in the process of moving to a new desktop computer, and this reminded of the post below on mechanical computers from ten years ago, where (back then) mechanical computation came up four times in the period of a couple of weeks.

The first example was when I was proofreading my 2015 title for St Martin's Press, called Ten Billion Tomorrows . The book about the relationship between science and science fiction, and I point out that when I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968 (in the cinema in Cinerama, an ultra-widescreen attempt to get people away from the TV), the only computer I had ever seen before I encountered the remarkable HAL was my Digi-Comp I. This was a mechanical device with three plastic sliders, which could be programmed by adding extensions on the side of the sliders which flipped metal wires, and as a result could provide the action of different gates and reflect the outcome on 3 mechanical binary displays. Sophisticated it was not. If I'm honest, while I managed to follow the instructions and get it to do some operations, it really taught me nothing whatsoever about computers.

Examples two and three involve good old Charles Babbage. You just can't talk about mechanical computers without mentioning Babbage. He first came up in my review of James Tagg's Are the Androids Dreaming Yet , which confuses an image of the Science Machine's Difference Engine with the Analytical Engine. (The Difference Engine was a hard-geared mechanical calculator, while the Analytical Engine, never built, was a programmable computer that would have used punched cards. Babbage built a small segment of the Difference Engine, but never got anywhere with the Analytical Engine, which almost certainly would not have been practical given Victorian engineering tolerances.)

Then Babbage popped up again in a Guardian article about a graphic novel featuring the Analytical Engine. As Thony Christie points out in a blog post, the article wildly overstated the contribution of Ada King* to the project saying that 'Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage designed a computer ... for which Lovelace wrote the programs.' In fact King had nothing to do with the design, she translated a paper on the concept from the Italian and added a series of notes. These included an example of what a program might be like. We have no evidence that she wrote this algorithm herself, and even if she did, it didn't make her the machine's programmer, or the first as Babbage had already written several.

The claim that King wrote programs comes up again in Matt Parker's entertaining Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension , which I was then reading for review. But of more interest is his description of building a working computer (admittedly only capable of adding up to 16) with 10,000 dominos by using the interaction of falling dominos to produce gates. This was a wonderful feat for which this tireless maths enthusiast should be congratulated. You can see the 10,000 domino computer in action below.

* I prefer Ada King to the more commonly used Ada Lovelace, though I admit I seem to be about the only one who does. Her full name was Ada King, Countess of Lovelace. While in principle a countess can be referred to by her title in place of surname, the usual reporting standard is to use the surname. So, for instance, when referring to the Duke of Bedford, he is called Andrew Russell, not Andrew Bedford. People sometimes get confused because the royals don't really have surnames, so there's no other choice with them. But I think with Ada it's primarily done because 'Lovelace' sounds more exotic.

Image by Pierre: Digi-Comp I (photo from Wikipedia)

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 14, 2025

A thank-you to the University of Buckingham - and thoughts on science and truth

On Friday, on a beautiful sunny day, I was delighted to be awarded an honorary Doctor of Science degree by the University of Buckingham.

On Friday, on a beautiful sunny day, I was delighted to be awarded an honorary Doctor of Science degree by the University of Buckingham.The whole day could not have been better, from being given a chance to give to speak to graduands from the IT and Health faculties (see below) to the honour of receiving the degree, hearing about remarkable work done in those faculties, and the pleasure of meeting fascinating people, from Sir Magdi Yacoub to the University Chancellor Dame Mary Archer (who I'm pictured above alongside). Not to mention sharing this with family and Buckingham-based friends.

Here's an approximate version of what I said to the students.

This excellent establishment was not granted royal charter until well after I left education, but is a place I would have been proud to attend for its open-minded approach. Basing decisions on evidence, not bias, is is so important when it comes to dealing with truth - and truth is something it's essential to understand in my job as a science communicator. Science is often portrayed simply as a search for truth, but I think it's important the public understands that the reality is more nuanced than this.

Part of the problem we face in explaining science is that researchers hope to achieve the next big thing so they can secure funding. This often leads to university PR departments over-hyping findings. My favourite example of this occurred a few years ago when Fox News trumpeted

Star Wars lightsabers finally invented

I think it's fair to say that many would expect Fox to go a little over the top, so to balance this from the more sedate end of the media, the Guardian reported

Scientists Finally Invent Real, Working Lightsabers

I just love the way they both say 'finally', as if to ask 'What have these scientists been doing all this time?' Intrigued, I took a look at the original paper that the press release was based on. It described how two photons - particles of light that usually ignore each other - briefly interacted in a special substance known as a Bose-Einstein condensate, cooled to near absolute zero. A lightsaber it was not.

This is an extreme example, but every day newspapers carry reports of the latest research findings - what this week's view is on the impact of red wine on your heart, for example. More often than not, these are preliminary findings that need further work to get anywhere near something that could be regarded as 'the truth.' Often there will never be certainty.

Most of the time science doesn't prove things. It's not really about absolute truth. Mathematicians can prove theorems because they control their environment. They define what the entities they work with mean - and the result is absolute mathematical truth. They don't have to deal with a messy, real world. Usually, though, the most we can say about science is that it gives us the best possible theory give current data - but we have to remember that this may change in the future.

For a science communicator this can be difficult to put across. People like things in black and white, with clear outcomes. But results often have to be interpreted statistically. In some fields, sample sizes are rarely big enough to have confidence in the outcomes. It's arguable too that some subjects that consider themselves sciences (dare I mention economics) may use the tools of science, but arguably aren't true sciences at all.

However, I don't say this to be negative about science. It has done a vast amount for us practically, as well as hugely expanding human knowledge, a joyful pursuit in its own right. The best possible theory given current data will always be far better than a random opinion on Tik Tok - scientific findings provide a wonderful resource as long as we understand what they are saying. And this is why I love being a science communicator. I'm not dispensing absolute words of wisdom and truth - that's more the remit of the clergy [the ceremony took place in Buckingham parish church]. I have the privilege of explaining these remarkable theories and why they provide the best understanding we have of the universe... unless new data changes our view.

I hope that with the open-minded and thoughtful approach the university has given to you, that you too can enjoy the fascination that arises from the scientific view of the world around us. By all means search for the truth - but make sure your truth is backed up by the best theory given current data. And if that's the case, you can't go far wrong.

Image by Peet Morris

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 8, 2025

Were astrologers the original p-hackers?

Science writers rarely mention astrology, other than to moan when someone accidentally uses the word instead of astronomy. There is, of course, no scientific basis for astrology, but when we are considering history of science it is impossible to ignore astrology as many of the early astronomers earned a fair amount of their living doing a spot of astrology on the side. This didn't mean that they necessarily believed in it (though Roger Bacon, for example, makes an argument for it as an environmental influence, as opposed to a predictor of the future), but it brought in the cash and often the support of the nobility.

Science writers rarely mention astrology, other than to moan when someone accidentally uses the word instead of astronomy. There is, of course, no scientific basis for astrology, but when we are considering history of science it is impossible to ignore astrology as many of the early astronomers earned a fair amount of their living doing a spot of astrology on the side. This didn't mean that they necessarily believed in it (though Roger Bacon, for example, makes an argument for it as an environmental influence, as opposed to a predictor of the future), but it brought in the cash and often the support of the nobility.The reality with astrology and other fortune telling approaches is that, even though it has no basis for working, inevitably some of the predictions will come true. If every single prediction didn't happen, it would actually be a very significant outcome - astrologers would be successfully predicting what wasn't going to happen.

I was struck the other day when writing about the dubious scientific result-generating mechanism of p-hacking that astrologers, in effect, do the same thing. The social sciences generally accept a 'p-value' of 0.05 as meaning that a finding is statistically significant. Getting this value tells us that if there were no genuine cause (the so-called 'null hypothesis' were true), the measured effect should occur about 1 time in 20 (hence 1/20 = 0.05). Before the practice was identified as being extremely dodgy, p-hackers would take a set of data from a study and slice it up in many different ways. If they got, say 40 different outcomes, then with a 1 in 20 chance of an apparent effect when the null hypothesis was true, the chances would be high that at least one of the outcomes would appear significant without any basis.

In a similar way, if a horoscope makes enough predictions, especially if they are vague, it is very likely that at least one of them will prove to be true. I admit Monty Python is showing its age, but the show's horoscope sketch still holds up well for demonstrating this exact principle when we get to the spectacles:

Image from Unsplash by Vedrana Filipovic.These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

April 7, 2025

Houdini's psychology fail

I'm currently enjoying Tim Harford's three part series on Houdini on his

Cautionary Tales podcast

. Although best remembered as an escapologist, in the later part of his life, Harry Houdini included a section in his act that involved unmasking spirit mediums as fake.

I'm currently enjoying Tim Harford's three part series on Houdini on his

Cautionary Tales podcast

. Although best remembered as an escapologist, in the later part of his life, Harry Houdini included a section in his act that involved unmasking spirit mediums as fake.Earlier, Houdini had become friends with Arthur Conan Doyle, who became a fervent spiritualist and whose wife was a medium. Apparently, in one final attempt to persuade Doyle of the folly of his beliefs, Houdini did a demonstration for Doyle in his New York apartment. He hung a small blackboard from the ceiling out of reach, asked Doyle to to go out of the apartment and write a message on a piece of paper. When Doyle returned, Houdini got Doyle to stick a cork ball soaked in white ink on the board - to Doyle's amazement, the ball then wrote out his message (the Aramaic phrase Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin - mentioned in the Bible's book of Daniel) on the board.

Houdini did this to demonstrate how the apparent abilities of spirit mediums could be reproduced and even bettered by using a magic trick. Doyle, unfortunately, simply didn't believe Houdini's denials and thought it was the act of a genuine medium.

But here's the odd thing. To be a stage magician you need to be a good psychologist. Yet it was almost inevitable that this would be the outcome. Houdini told Doyle he wasn't going to explain to him how the trick was done - Doyle had to take Houdini's word for it that it was faked. In my recent book Brainjacking, in a chapter on deception, I look at how Derren Brown describes using psychology to build the impact of a simple trick. But this only really works because in his book, as part of doing so, Brown describes how the trick works.

You might say, 'But magicians can't explain their tricks, or they lose their mystique'. However, it seems that Houdini had learned magic originally from a book. And there was nothing to stop him saying to Doyle he would tell how the trick worked as long as Doyle - a gentleman who wouldn't break his word - swore not to tell. The only way this 'proof' would have succeeded was if Houdini had thought a little more about the psychology of his interaction with Doyle. Things could have ended very differently.

If we are to unmask deception (or disinformation) we need to be careful not to be practising deception ourselves as part of the attempt.

Image from Unsplash by The National Library of WalesThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 2, 2025

Chlorine-washed chicken panic? Choose your battles...

Whenever the possibility of a trade deal between the UK and the US crops up, 'chlorinated' chicken comes back to menace us, much like Frankenstein's monster. But really it's a paper tiger. (This must surely be a mixed metaphor?)

Whenever the possibility of a trade deal between the UK and the US crops up, 'chlorinated' chicken comes back to menace us, much like Frankenstein's monster. But really it's a paper tiger. (This must surely be a mixed metaphor?)There is no doubt that there are potential dangers to such a deal for the UK, notably around food and medical supplies and services. However, when the press gets over-excited about chlorinated (or more properly chlorine-washed) chicken, it dilutes the whole argument, because this is absolutely fine.

If you buy a bag of ready-to-eat salad in the UK it will have been chlorine-washed. This kills off the dodgy bacteria such as E. coli, Salmonella and Listeria that can easily be carried by salad leaves - the treatment makes it safer to eat. No one seems to panic about this. Now let's consider chicken. In the old days we used to be told to wash chicken before cooking it. We don't anymore because there is a real danger that doing so will splash the dodgy bacteria that chicken carcasses are likely to have on them, such as Campylobacter and Salmonella, into the air, making them easier to breathe in and cause an infection. All chlorine washing does is to kill off those bacteria before packaging. The case against using chlorine-washed chicken is that makes lower welfare standards easier to maintain - but bear in mind that despite our standards, the majority of chicken sold in the UK does carry such bacteria.

So, please, stop moaning about debugged chickens. By all means dig into the less salubrious aspects of US food and medical deals, but don't get distracted by the less than foul fowl.

Image from Unsplash by J K Sloan.These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereMarch 31, 2025

Electric cars and government revenue

Many decisions that a government takes have unwanted side effects. For example, while everyone surely thinks it's a good idea to stop people smoking, the government takes £6.50 plus 16.5% of the retail price from every packet of cigarettes: tobacco duties raise about £8.8 billion a year at the moment.

Many decisions that a government takes have unwanted side effects. For example, while everyone surely thinks it's a good idea to stop people smoking, the government takes £6.50 plus 16.5% of the retail price from every packet of cigarettes: tobacco duties raise about £8.8 billion a year at the moment. The response is often 'yes, but if we can get people off cigarettes it would reduce costs to the NHS'. It would - but only by an estimated £2.6 billion. So the exchequer would still be £6.2 billion a year worse off if we got everyone to stop.

There is a similar issue with electric cars. At the moment, the fuel duty on petrol (gasoline) and diesel in the UK raises an eyewatering £28 billion annually. If we could wave a magic wand and switch everyone overnight to electric vehicles, that income would currently disappear. And though drivers might cheer, the government would certainly not be happy. So for some time there have been schemes afoot to recoup these potential losses. I gather from a press release that an organisation I was unaware of called the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport UK (CILTUK - who pays for these bodies?) is 'urging the government to start talks with experts to tackle the impending black hole in the income from fuel duty.' Don't politicians love a good black hole?

CILTUK has produced a detailed report, but here are the headlines. Although the report's primary recommendation is that the government needs to consult with industry experts and stakeholders (perhaps even motorists?), which is hardly a result that needed a lot of thought, there are some specific-ish proposals. The report's authors suggest we need an approach that 'motorists will view as reasonable and balanced... and [is] simple and easy to understand, inexpensive to collect and resistant to fraud.' So far, so good.

What they don't do is give us any picture of how such a revenue-raising scheme would work in practice, though the report does mention the London congestion charge. Reading between the lines, they appear to be advocating a mix of congestion charging for cities and pay-per-mile, with encouragement for car-sharing or using alternative transport.

I sort of agree with this. I'm quite happy not to drive into cities and I do see that we need to reflect road usage to have a fair form of taxation - but the devil will certainly be in the detail, and I find it hard to see how it will be possible to come up with a combination of 'reasonable and balanced', 'simple and easy to understand' and 'inexpensive to collect'. That feels like a recipe for a messy system.

After all, what you might regard as balanced if you are, for example, a single person driving from a village to the supermarket (because it's the only way to get there) versus a potential car-sharing collection of people commuting to work (when they arguably should be working from home) might be difficult to achieve. Similarly, systems requiring every vehicle to carry a GPS black box would be expensive, so the most likely approach would be numberplate recognition. The good news is that such systems are well-established, but the downside is that a universal spread of them would both impinge on civil liberties - privacy would become almost impossible - and would be worrying as they aren't infallible.

The flaws aren't so obvious with something like a camera used to register crossing a toll bridge, because it's a one-off measure. But if the system measures distance travelled by catching you going into and out of a stretch of road, there is a danger it will suffer from the same issues we see in our local shopping centre car park. You are allowed to stay two or three hours. But people regularly receive fines if they visit in the morning, then again in the afternoon because the cameras missed their exit in between. This would scale up massively with road charging based on numberplate recognition.

It may be possible to devise something fair and equitable, taking into account different needs. I hope it is. But I'm not convinced the suggested measures of success are achievable. For the moment, I enjoy every electric, fuel-duty-free mile with my plug-in hybrid.

Image from Unsplash by Chuttersnap

This has been a Green Heretic production. See all my Green Heretic articles here.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

March 28, 2025

No super cars for me revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from March 2015

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from March 2015Every now and then I get a semi-spam email (i.e. something I probably accidentally signed up to receive, but never really wanted) offering me the opportunity to buy cut-price 'treats', like a super car experience. I know some people love this kind of thing, but I just don't get it.

I've got three problems with the whole 'super car experience' thing. But before that, I need to distinguish this from the early Gerry Anderson series, which I loved as a boy. Here in the UK it was a black and white series, but it appears from the DVD that it was shot in colour. For primary school me, the best thing about it was that our Ford Anglia was excellent for playing Supercar, as the heater controls (the heater was an optional extra) made an excellent substitute for throttles, and it even had little fins on the tail, though they aren't visible in my picture below. However, I am not referring to Supercar, but rather an 'experience' day where you get to drive something like a Ferrari or an Aston Martin. My first issue is that I wouldn't actually want one of these cars as they are incredibly impractical (anyone remember the Top Gear where the presenters tried to get three out of an underground car park in Paris?), they're ludicrously expensive and they make a silly noise. I've never understood the appeal of the sort of noise that boy racers try to imitate by having a dustbin in place of an exhaust pipe on their Ford Fiesta. It sounds loud, nasty and industrial. My favourite car noise is an electric car - but that's a different story.

My first issue is that I wouldn't actually want one of these cars as they are incredibly impractical (anyone remember the Top Gear where the presenters tried to get three out of an underground car park in Paris?), they're ludicrously expensive and they make a silly noise. I've never understood the appeal of the sort of noise that boy racers try to imitate by having a dustbin in place of an exhaust pipe on their Ford Fiesta. It sounds loud, nasty and industrial. My favourite car noise is an electric car - but that's a different story.The second problem is that on an experience day they wouldn't just give you the keys and say 'Have fun,' they would expect you to drive it around a track, with experts looking on and sniggering at your inability to 'take the correct line' or brake at the sweet spot, or G spot or whatever it is. I did once accidentally go to a track day, and quite enjoyed being driven around by an expert (scary though it was), but there was no way I was going to do it myself, in front of others.

Most importantly, though, if I did have a drive in a super car (and if I did, it would be an Aston Martin, no question), it would have to be my own vehicle. I don't understand the envy-driven gratuitous excitement of having a go at something you can't actually have. It's a phenomenon that's quite closely related to pornography, perhaps most closely in those house porn 'Escape to the Country' style house programmes where people who are selling a 3 bed semi in London look round 10 bathroom mansions in the country, which normal people could never afford, so they watch the programme to drool instead. It's one of the nastiest aspects of capitalism.

So there you have it. Super car experiences are for those whose existence is unsatisfactory. Get, as they say, a life.

The Supercar DVD set is available from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com. Anglia photo by the author

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

March 24, 2025

Tuesday's child is... downright confusing

Having recently revisited the Monty Hall problem, I thought it was worth also taking a look another, arguably even more mind-boggling probability problem that also got Marilyn vos Savant a lot of complaints when she included it in her column.

Having recently revisited the Monty Hall problem, I thought it was worth also taking a look another, arguably even more mind-boggling probability problem that also got Marilyn vos Savant a lot of complaints when she included it in her column.The problem sounds trivial enough, and comes in the form of a statement for which we have to predict the probability. It reads ‘I have two children. One is a boy born on a Tuesday. What is the probability that I have two boys?’

It sounds trivial. The Tuesday bit is just window dressing, so we are looking at ‘I have two children, one a boy. What is the probability I have two boys?’ So with one child a boy, surely there is 50 per cent chance that the other child is a boy and a 50 per cent chance it’s a girl. Which makes the probability of having two boys 0.5, or 50 per cent. There’s a one in two chance.

But unfortunately that is not correct.

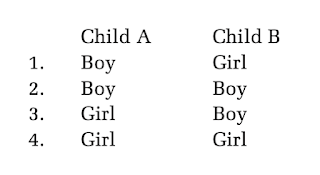

The reason we get confused is that when trying to imagine the situation we think of the ‘first’ child we come as a boy, then look at the options for the second child being a boy. However the description of the situation would also work if the first child is a girl and the second child is a boy. The only way to be absolutely certain is to work through every possible combination:

These are the four possible combinations, each equally possible. Of these, three are situations that match my initial statement ‘I have two children, one is a boy’. In all but case 4, one of the children is a boy. But only one of those three combinations with a boy also makes the second child a boy. So the answer to ‘I have two children, one a boy. What is the probability I have two boys?’ is not 50 per cent, or one in two, it is one in three. This part of the problem is probably on a par with Monty Hall in the difficulty of getting your head around it. But there is a more fiendish part. We were wrong to discard the Tuesday. Saying the boy was born on a Tuesday changes the probability.

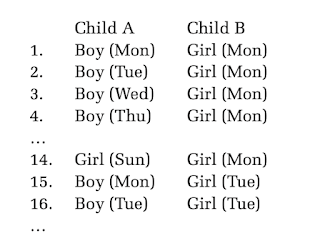

To see this we need a much bigger table. It starts like this:

In total we have 196 entries in this table. We go through every single sex/day combination in the first column combined with a girl born on Monday (fourteen of them in all), then every single sex/day combination in the first column combined with a girl born on Tuesday (fourteen of these too) and so on until we have cycled through every option for the second child.

Now we need to know two things. How many of those pairs feature a boy born on a Tuesday (like option 2 above) and how many of those have a second boy? We are going to have one combination of child A as a boy born on Tuesday with every possible child B – fourteen of those, plus thirteen other combinations where child B was a boy born on Tuesday, but child A wasn’t (we have already counted the instance were both child A and child B are a boy born on Tuesday). So there are 27 rows that match our circumstance of having a boy born on Tuesday.

We now need to pin down how many of those rows had two boys. The first set of fourteen all had a boy as child 1, and half of those – seven also had a boy as child 2. Of the thirteen additional rows where child B was a boy born on a Tuesday, six would have child A also a boy. So of the 27 rows with a boy born on a Tuesday, thirteen of them have a second boy. The answer to ‘I have two children. One is a boy born on a Tuesday. What is the probability I have two boys?’ is 13 in 27 – almost, but not quite, one in two.

This really upsets common sense. Just by specifying the day on which one of the children was born we change the probability of both children being boys from one in three to 13 in 27. Yet our minds rebel at this. Surely we could have chosen any day? The only way I can see to make some sense of this is to point out that in any particular real circumstance, you can’t choose that day at random; it is extra information that depends on the circumstance. The boy will have been born on a particular day and the result of that is that it cuts down the options, just as Monty Hall did when he opened a door and showed a goat. The reality is even harder to accept in this example.

There's lot's more on the beguiling nature of probability in my book, Dice World.

Photo by the author

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

March 22, 2025

Confusing metaphor and physical reality

There's nothing the right-wing newspapers like more than a touch of wokeness-gone-mad - and back in February this was trumpeted by an article in the Daily Telegraph headlined Lego can be anti-LGBT says Science Museum (this is behind a paywall, but I was able to access it via Apple News). The story has since been picked up by many other news outlets.

There's nothing the right-wing newspapers like more than a touch of wokeness-gone-mad - and back in February this was trumpeted by an article in the Daily Telegraph headlined Lego can be anti-LGBT says Science Museum (this is behind a paywall, but I was able to access it via Apple News). The story has since been picked up by many other news outlets.The outrage in the press is based on a self-guided tour called Seeing Things Queerly telling visitors that 'Like other connectors and fasteners, Lego bricks are often described in a gendered way. The top of the brick with sticking out pins is male, the bottom of the brick with holes to receive the pins is female, and the process of the two sides being put together is called mating. This is an example of applying heteronormative language to topics unrelated to gender, sex and reproduction. It illustrates how heteronormativity (the idea that heterosexuality and the male/female gender binary are the norm and everything that falls outside is unusual) shapes the way we speak about science, technology, and the world in general.'

A starting point here is to make it clear that, as is often the case, the headline gets it wrong. The same applies to many other outlets, for example The Times (Lego is anti-LGBT and promotes only two genders, says Science Museum). Perhaps surprisingly, Fox News gets closer with 'Science Museum claims Legos push a "heteronormative" agenda in LGBTQ tour'.

However, there remains a significant issue with the tour wording. It is true that it is common to use male-female terminology to lots of things (plugs and sockets, for instance), with 'male' as the sticky-out bit and 'female' as recessed-in bit. And, these are indeed 'topics unrelated to gender, sex and reproduction.' But I have never heard the process of joining two Lego bricks described as mating. And no evidence is provided that the use of male/female illustrates the idea that heteronormativity is the norm and everything that falls outside is unusual. It is simply a useful metaphor.

The objection is a bit like claiming that having a paint shade called 'swan white' involves cygnusnormativity because some swans are black. We still know what it means. The male/female thing is a useful metaphor, reflecting the majority of gendered organisms. The authors of the tour seem to confuse metaphor with reality. It seems, then, despite those misleading titles, there is something a little worrying about the wording used.

Image from Unsplash by Xavi CabreraThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Article by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

March 17, 2025

The joy of dodgy studies

As a science writer I get sent lots of press releases about scientific studies. Some describe serious research, but there is always a smattering of studies sponsored by companies with entertaining PR in mind (think the ones that give the formula for making the perfect sandwich, or some such thing), rather than any scientific outcome. I've just received the most entertaining one I've had in some time, which I feel needs sharing. The press release opens with:Born in August and named John or Mary? You might be a genius.A new study analysing more than 1,000 of history’s greatest minds reveals common traits among the world’s smartest people—from birth month to name. Could you be one of them?

As a science writer I get sent lots of press releases about scientific studies. Some describe serious research, but there is always a smattering of studies sponsored by companies with entertaining PR in mind (think the ones that give the formula for making the perfect sandwich, or some such thing), rather than any scientific outcome. I've just received the most entertaining one I've had in some time, which I feel needs sharing. The press release opens with:Born in August and named John or Mary? You might be a genius.A new study analysing more than 1,000 of history’s greatest minds reveals common traits among the world’s smartest people—from birth month to name. Could you be one of them?You might think this study was performed by a publicist with a degree in dog grooming (say), but unlike many such press releases, it does refer to an original paper. Admittedly they get that a bit wrong, saying it was 'published on ResearchGate' which is a portal - it was published in Current Psychology, which is a Springer Nature journal. It is also from 2022, so not exactly new, but this is because the company behind the press release, World of Card Games, has apparently conducted 'an original analysis of the 1,000+ historical figures to identify patterns in names, birth months, and zodiac signs among geniuses'.

The ResearchGate link is a systematic review of studies that attempt to show 'how a name influences its owner’s personality, decision-making, and life outcomes.' I haven't been able to obtain a full copy of the paper, but I do have a slight concern about its quality when I read in the introduction 'To give the new coming to a survey of the forest, not the trees, we concluded the current literature to three approaches...'. It is, of course, possible that the review concluded all this stuff is timewasting nonsense, but the abstract gives no clue as to whether or not there was any critical analysis of the sources reviewed.

What's of interest here are the key findings from the 'original analysis' undertaken by World of Card Games, which, according to the release, are:

Key findings:John is the most common name among geniuses, appearing 18 times (1.60%) among history’s most acclaimed inventors, scientists, mathematicians, and entrepreneurs.Mary leads among female names with 15 occurrences (1.33%). Other top names linked to intellectual and entrepreneurial success include Margaret (14, 1.25%), Maria (13, 1.16%), and Elizabeth (12, 1.07%).August is the top birth month for brilliant minds, with 117 renowned figures (10.41%) born in this month. February (101, 8.99%), November (101, 8.99%), July (96, 8.54%), and April (94, 8.36%) follow closely.Leo is the most common zodiac sign, with 114 notable figures (10.14%). Taurus (101, 8.99%), Aries (101, 8.99%), Aquarius (97, 8.63%), and Scorpio (96, 8.54%) round out the top five.If we ignore star signs per se for the obvious reason that astrology is baloney, but simply consider the birth dates (that's all star signs tell us, after all), we see relatively little variation in the lower rated months/signs - certainly too little to be statistically significant - but the tweak up for August/Leo is slightly interesting, even though it is almost certainly just the scale of outlier we might expect. It is worth noting that around this time of year (September more accurately) tends to have a birth peak, due to the celebrations 9 months earlier. I did find it odd that May doesn't come in the top 5 months, despite Taurus (two-thirds of which is in May) being second equal - that feels dubious.

What is absolutely hilarious, though, is the names part. Here we have to dig out that old trusty statistical mantra that correlation is not causality. Just because A (name) and B (genius) appear to be linked does not imply that A causes B. It could be pure coincidence, or equally it could be the other way around that B causes A (admittedly, unlikely here) or a third factor causes both (very likely here). In a good quality, real study, you would control for obvious 'confounding' factors - something else that linked A and B.

A particularly obvious such factor jumped out to me, and with all of 2 minutes research it appears to be highly likely to be the main cause. Historically, popularity of names changed much slower than it does now. If we look at the most popular boys' and girls' names in the UK, for example, 100 years ago, they were John and Mary. Hmm. Do they look familiar?

What have we discovered, then? Nothing to see here, folks. Move along.

Image from Unsplash by Andrew George. Of course, Albert was not one of the top names, and Einstein was born on 4 March, making him an apparently less than high-performing Pisces.These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here