Brian Clegg's Blog, page 9

December 18, 2024

A mirror to Life on Mars

Watching the mildly entertaining Man on the Inside on Netflix, I was struck by a painful mirror image of the bad old days. In the series Ted Danson plays a bored, retired engineering professor who takes on a job as an undercover investigator for a PI to investigate a theft in a retirement home. We get some stereotype old people behaviour, but also some embarrassingly hypocritical sexism.

Watching the mildly entertaining Man on the Inside on Netflix, I was struck by a painful mirror image of the bad old days. In the series Ted Danson plays a bored, retired engineering professor who takes on a job as an undercover investigator for a PI to investigate a theft in a retirement home. We get some stereotype old people behaviour, but also some embarrassingly hypocritical sexism.I'll come back to that in a moment, but to put it into context, I've also recently been rewatching the excellent 2006/7 TV series Life on Mars. In the show, the 2006 detective Sam Tyler played by John Simm hallucinates himself into a 1970s Manchester police team after a brain injury, working under the wonderfully unreconstructed Gene Hunt (Philip Glenister). Something Tyler constantly attempts to battle is the casual sexism of the male detectives, which (allegedly) had changed significantly by 2006.

Now back to Man on the Inside (made in 2024, not the distant past). Two female inhabitants of the retirement home are blatantly sexist, commenting on the body of a young man in a video, then getting a young male worker to plug something in, so that they can look at his rear end. Just imagine this had been the mirror image and old men had been discussing the body of a young woman - it would be absolutely creepy... and so was this.

Some might argue that it's okay because men got away with it for so long - but that's pure 'two wrongs don't make a right' territory. I do see this quite a lot where somehow it's considered okay for women to make remarks about men's looks that (rightly) would be totally unacceptable the other way round. At least Life on Mars was critiquing the 70s. But surely we've moved on since then?

Image by Brendan Church from Unsplash

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereDecember 17, 2024

Sherlock Holmes and the Twelve Thefts of Christmas - Tim Major ***

As a fan of Sherlock Holmes on the lookout for a Christmas mystery, this seemed an ideal purchase - and it's not bad. But it's not great either. There have been some excellent modern Holmes ventures - think, for example, of Anthony Horowitz's

House of Silk

, and even more so his brilliant

Moriarty

. And on the whole Tim Major makes a reasonable effort of fitting with the characters as we know them - but there are two issues with the way the book's written.

As a fan of Sherlock Holmes on the lookout for a Christmas mystery, this seemed an ideal purchase - and it's not bad. But it's not great either. There have been some excellent modern Holmes ventures - think, for example, of Anthony Horowitz's

House of Silk

, and even more so his brilliant

Moriarty

. And on the whole Tim Major makes a reasonable effort of fitting with the characters as we know them - but there are two issues with the way the book's written.To give it some context, this is a story featuring Irene Adler (who the TV show Sherlock demonstrated well was ideal for taking Holmes in something of a new direction), who is setting Holmes a series of puzzles, starting with an odd sounding vocal performance which he studies at some length as sheet music. All the puzzles, it appears, are to be thefts with no theft - perhaps the cleverest these involves a stolen painting that never existed. And there is some entertainment as Holmes and Watson attempt to get a grip on these, while also trying to reconcile an apparent murder with Adler's supposedly light-hearted intentions. But there also some problems here.

Major's writing style drifts too far from Doyle's - this is particularly apparent in the behaviour of Mrs Hudson, who seems to have lost her wits (and sometimes uses wording more suited to the version in the current-day TV show). And Holmes is both ridiculously incommunicative and given to strange behaviour. Of course, the original could be intentionally obscure, but this Holmes is downright obstructive to Watson. As for the 'twelve thefts', while a few of these are clear, many of them are vague references that we never really are sure have anything to do with the plot, in a book that ends in a way that Doyle would not have countenanced.

I got through the book, and enjoyed it in part, but the author neither had Doyle's style nor his ability to weave a plot without ending up with a messy tangle of threads.

You can buy Sherlock Holmes and the Twelve Thefts of Christmas from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

December 13, 2024

Murder by Candlelight - Ed. Cecily Gayford ***

Nothing seems to suit Christmas reading better than either ghost stories or Christmas-set novels. For some this means a fluffy romance in the snow, but for those of us with darker preferences, it's hard to beat a good Christmas murder.

Nothing seems to suit Christmas reading better than either ghost stories or Christmas-set novels. For some this means a fluffy romance in the snow, but for those of us with darker preferences, it's hard to beat a good Christmas murder.An annual event for me over the last few years has been getting the excellent series of classic murderous Christmas short stories pulled together by Cecily Gayford, starting with the 2016 Murder under the Christmas Tree. This featured seasonal output from the likes of Margery Allingham, Arthur Conan Doyle, Ellis Peters and Dorothy L. Sayers, laced with a few more modern authors such as Ian Rankin and Val McDermid, in some shiny Christmassy twisty tales. I actually thought while purchasing this year's addition 'Surely she is going to run out of classic stories soon' - and sadly, to a degree, Gayford has.

The first half of Murder by Candlelight is up to the usual standard with some good seasonal tales from the likes of Catherine Aird, Carter Dickson and Dorothy L. Sayers. But the remainder, while most quite good only just touch on a winter connection (if at all), let alone having the Christmas setting. To make matters worse, the longest story in the book is the dire The Mystery of the Sleeping-Car Express by Freeman Willis Crofts. This plodding train-based locked room mystery is dull in the extreme. It might have been rescued a touch by a clever twist at the end - but the solution is pedestrian.

As a whole it's not a disastrous book, but unlike all its predecessors it's going on the 'dispose' pile rather than my shelves for re-reads. Don't be put off from the series, though, if you like this kind of thing - there are plenty of delights in all the earlier volumes.

You can buy Murder by Candlelight from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org but you'd be better off with the likes of Murder under the Christmas Tree, also from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

December 12, 2024

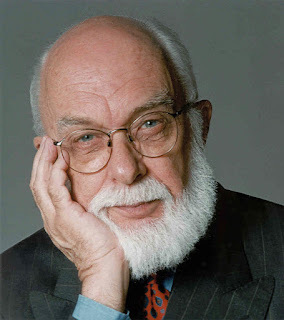

Don't put magicians on pedestals revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An edited post from December 2014

REVISIT SERIES - An edited post from December 2014Over the years, magicians like Harry Houdini and James Randi have shown time and again that they have ideal skills for spotting and debunking fraudulent claims of magical abilities and mental powers. In the Telegraph newspaper, though, Will Storr had a go at 'debunking the king of the debunkers', demonstrating that Randi himself, now 87 (according to his article, or 86 according to Wikipedia), was not all he seemed. [Randi died in 2020.] For me, this was a wonderful example of entirely missing the point.

Storr made three main accusations. That Randi has at some point been doubtful about the science behind climate change, that he was intolerant to drug users and that he had lied about replicating Rupert Sheldrake's dog experiments, in which Sheldrake claims to have shown that at dog was able to predict when its owner would return home.

The first two, frankly, are hardly worth considering as they are classic type errors. Being good at debunking fraudulent psychics does not make you a climate change expert. Why should it? And some perfectly respectable scientists have doubts about some aspects of climate change science. It's the nature of science - it's not a belief system where you have to sign up to everything it says in the big book. As for Randi's attitude to drug users, again, so what? So that leaves us with the strange incident of the dog.

It seems likely, if we take Storr's article at face value, that Randi did indeed claim to have replicated an experiment when he hadn't done so. This isn't good. But in a sense it is the inevitable reverse face of the reason that Randi has done his job so well in the first place. Randi has always argued that scientists are not very good at devising tests that prevent those with a stage magician's skills from cheating, or at detecting such cheating in action. What you need, he says, is a magician. And he has proved time and again that he is right. Scientists don't have the expertise of a magician. Well, guess what? Magicians don't have the expertise of a scientist either. Randi isn't a scientist. So why are we surprised when Randi fails to operate in a proper scientific fashion over the Sheldrake business?

In fact, in his own writing, Randi has made scientific errors. In his book Film Flam he comments 'Jack van Impe, a TV evangelist who perspires and preaches his version of science regularly to millions of believers, recently gave us an Easter message that reflected his ignorance of science. He referred to the preposterous "Jupiter Effect" so beloved of some nuts, which is supposed to cause wonderful catastrophes in 1982. The Earth should be a mess at the end of this claimed alignment of the planets, and I can hardly wait to see the show. Said Jack, "The Earth will be seven times hotter." Codswallop. The term has no meaning. "Seven" is a number, Jack. If you take the normal temperature to be 70 degrees Fahrenheit, that makes the new reading 490 degrees Fahrenheit. If you're in Europe or Canada, that same temperature is 21 degrees Celsius, giving the other folks a break with 148 degrees C, which is equal to only 298 degrees F.'

Yes, of course seven is a number - but that doesn't mean that something can't be seven times hotter than something else. Temperature is a measure of the mean kinetic energy of the atoms or molecules in a substance, and one thing can have seven times as much energy as another. So something can be seven times hotter than something else. (Or the world can be seven times hotter at one point in time than it is at another.) What Randi is really identifying is the arbitrary nature of the temperature scales he uses in his illustration. (And the stupidity of the prediction, which not surprisingly never came true.) If Randi had used the Kelvin scale, the numbers would be fine. But the way he phrased his attack shows that he too can get it wrong when working outside his field of expertise.

I'm not defending Randi in any way for what he is accused of doing. If his claim of replicating the Sheldrake experiment wasn't true, it was bad science, the kind of thing that gets a scientist kicked out of his job. But it doesn't in any way detract from the useful service Randi has provided over many years in devising tests and pointing out the flaws in scientific studies of ESP and the like. Has Storr shown that Randi is sometimes a liar? Quite possibly - and that's why he's good at his job. All magicians are liars by trade, even if they don't always use words to do it. More precisely, they indulge in Brainjacking - you'll find a lot on the work of magicians in my new book of that name. Deception is their business. Perhaps the problem is the fuzzy nature of Randi's skeptical foundation JREF, which gave the veneer of science to what never really deserved that label. Since Randi's death the foundation seems to have largely faded away - the last post on their website is from 2022.

When I read Storr's article, I got the impression of reading the words of a fan who discovers his idol has feet of clay. The same as those who discover their favourite singer has an unpleasant private life. Or that a Nobel Prize winning scientist had unacceptable views on other topics. Welcome to the real world, Mr Storr.

Image by Eduardo Aparicio from Wikipedia

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereDecember 11, 2024

Snow Crash reread

Back in 2016 I belatedly reviewed Neal Stephenson's 1992 novel

Snow Crash

- it seemed a good time to revisit and dive into it a little more than was possible in a straightforward review. Back then I commented 'If you like the kind of science fiction that hits you between the eyes and flings you into a high-octane cyber-world, particularly if you have an IT background, this is a masterpiece.' That certainly holds true of the first half.

Back in 2016 I belatedly reviewed Neal Stephenson's 1992 novel

Snow Crash

- it seemed a good time to revisit and dive into it a little more than was possible in a straightforward review. Back then I commented 'If you like the kind of science fiction that hits you between the eyes and flings you into a high-octane cyber-world, particularly if you have an IT background, this is a masterpiece.' That certainly holds true of the first half.Perhaps the closest parallel here is the 2010 Christopher Nolan film, Inception. Both are scintillatingly delightful, but tail off at the end. The movie, still one of my favourites, loses it somewhat when it turns into a sub-Bond action movie and then ends oddly. By contrast, Snow Crash gets distinctly bogged down by an interminable section where main character Hiro is doing the metaverse equivalent of library work on a convoluted theory that combines the Babel story and some Chariots of the Gods-like uber-speculation, which becomes somewhat tedious.

As is the case with Inception, the final denouement doesn't feel a good fit to the rest, with the treatment of the other main character, Y. T. reduced for much of that section to damsel-in-distress mode - jarring when compared with her intelligent and resourceful nature when armed with a skateboard. I was even more struck than I was when first reading the book in 2016 that Y. T.'s brief relationship with a psychotic killer was worryingly paedophilic.

It's impossible, though, not to admire the imagination that Stephenson deployed in Snow Crash. First there's a totally deregulated USA, where the only 'laws' are those enforced by corporations - a future that feels worryingly closer now, given recent political changes in the country. And second, there's the whole concept of the metaverse. There had been many other stories of virtual reality worlds, but Stephenson gives us one that is based not on the purely imaginary technology of something like The Matrix, but where the realities of his understanding coding shine through.

Of course there are limits to that imagination's ability to probe the future. Where Stephenson's metaverse is far more sophisticated than anything we have now, his characters still carry calculators alongside their basic phones. But bearing in mind that in 1992 major computing corporations still had very little interest in the internet, and the web had only been opened to the public one year before and was still primarily text-based, this remains extremely impressive.

I'm sure that most tech entrepreneurs have read Snow Crash - and given Meta's name, its concepts are hard to avoid. But perhaps those with political inclinations should also take note of the less than savoury aspects that come through in Stepehenson's book when they think of the future.

You can buy Snow Crash from Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Image by UK Black Tech from UnsplashThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereDecember 9, 2024

Letter from the Dead - Jack Gatland ****

Jack Gatland (real name Tony Lee) has an extremely slick writing style - it feels almost like an American crime writer producing a novel set in the UK. The setting is reminiscent of a police version of Mick Herron's Slough House intelligence service novels, televised as Slow Horses. Where that series involves a set of misfit, but in their odd way highly capable, spies, here we get the brilliant rejects of the police service, collected as 'The Last Chance Saloon'.

Jack Gatland (real name Tony Lee) has an extremely slick writing style - it feels almost like an American crime writer producing a novel set in the UK. The setting is reminiscent of a police version of Mick Herron's Slough House intelligence service novels, televised as Slow Horses. Where that series involves a set of misfit, but in their odd way highly capable, spies, here we get the brilliant rejects of the police service, collected as 'The Last Chance Saloon'.Herron's series predates Gatland's by five years - yet despite only starting it four years ago, the prolific Gatland has already produced 20 titles in the DI Walsh series, with other books alongside. You might imagine this would result in sub-standard writing. There are certainly more little errors than I would usually expect in a professionally published series, but Gatland has some excellent over-the-top plotting, and really keeps the tension up and the action flowing.

To illustrate, I can give an example of each from the second book in the series, which I'm currently reading. A trivial but irritating example of the little mistakes that frequently occur is that we have a Catholic referring to a priest as a vicar. But, to counter this, there's a brilliant bit of plotting in book 2 (Murder of Angels) where a body is discovered and forensically identified, only to have another body with the same forensic markers dug up somewhere else.

As well as Herron's books I was also reminded of Ben Aaronovich's Rivers of London series. Letter from the Dead isn't fantasy, but it does have that same feel with the camaraderie of outsiders in the police unit. In this first book in the series, the main character Declan Walsh is in danger of being suspended after both hitting a clergyman and uncovering corruption at a police station. But instead he joins the Last Chance Saloon to help solve a murder from years previously after new evidence comes to light. The main suspects were MPs at the time, but are now a contender for Prime Minister, a TV evangelist and a homeless drunk.

At the same time there is an underlying suspicion that Walsh's recently deceased father was killed, though there is as yet no evidence, giving an extended story arc that will no doubt run across several novels. It's a genuine page turner and I'll be back for more.

You can buy Letter from the Dead from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

December 3, 2024

The unnerving nature of collider bias

Not for the first time, I was inspired by listening to the excellent The Studies Show podcast. In their 26 November edition, Tom Chivers and Stuart Ritchie introduced collider bias, which is a horrible statistical anomaly that can make it seem that a study shows something entirely different from reality. What's particularly worrying is that, as the podcast demonstrates, many scientists aren't aware of this potential issue.

Not for the first time, I was inspired by listening to the excellent The Studies Show podcast. In their 26 November edition, Tom Chivers and Stuart Ritchie introduced collider bias, which is a horrible statistical anomaly that can make it seem that a study shows something entirely different from reality. What's particularly worrying is that, as the podcast demonstrates, many scientists aren't aware of this potential issue.I had assumed collider bias would be something to do with the kind of huge statistical analysis necessary to interpret what's going on in a piece of equipment like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN - but in reality the 'collision' in question is simply down to the way a pair of arrows point to the same location on a kind of flow diagram. What this statistical anomaly can produce, though, is the kind of result we love to hear (and scientists love to find) - results that make you go 'Huh? That's surprising.'

Examples given included that of those hospitalised with COVID-19, smokers were more likely to survive than non-smokers; amongst cardiovascular disease sufferers, obese patients live longer; success at basketball is not linked to a player's height; and PhD candidates who have high scores in the tests often used to decide if someone should start on a PhD are not more likely to succeed than those who score badly.

To understand this, Tom and Stuart ask us to imagine a study of Hollywood stars. They suggest you get to be a Hollywood star because you are either beautiful or a talented actor (or both). Assuming more actors major on one attribute than both, then, for the population sample that is 'Hollywood stars', you will find that beauty is negatively correlated with acting talent. Actors with talent, it would seem, tend not to be beautiful, and vice versa. This would be statistically true, but there is no causal link. The real danger is then to apply the same reasoning to the population at large and think that to be a great actor, a person should be ugly. But it's an artefact of the way Hollywood stars are chosen, not a true causal relationship.

In the surprising examples mentioned above, where this has occurred in real studies (often resulting in convoluted arguments as to why, say, being obese gives better survival from cardiovascular disease), it's because in each case we are looking at a sub-population - for example professional basketball players or PhD candidates, not considering people at large. So, for example, successful PhD candidates tend to be either highly intelligent or very hard workers (or both). But by only looking at successful PhD candidates, those two groups will dominate, where looking at the population at large, highly intelligent (and hence high scoring) people will be more likely to gain a PhD.

In their podcast (to be honest, one of their more meandering episodes, as this is a really difficult effect to describe), Tom and Stuart point out that this is relatively easy to spot when the result is so counter-intuitive, a reasonable flag to check if there is something wrong with the analysis. But the error can be missed if it's less stand-out.

Arguably a starting point should be that if you are studying a group that isn't typical of the population at large, then you need to be aware of this danger. This should be of particular interest, for example, to psychologists, who often do studies using university students as participants, because they are cheap and readily available. Unfortunately, though, they may well beg a collider bias population just waiting to happen. Take a listen to the podcast to find out more.

Image by Brandon Style from Unsplash... but it's not that sort of collider.These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereDecember 2, 2024

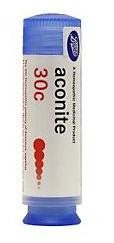

Homeopathy revisited

REVISIT SERIES - Edited posts from February 2010 and March 2015I've long marvelled at the success of the wonderfully unscientific concept of homeopathy. This is a double-length post pulling together two homeopathic adventures.

REVISIT SERIES - Edited posts from February 2010 and March 2015I've long marvelled at the success of the wonderfully unscientific concept of homeopathy. This is a double-length post pulling together two homeopathic adventures.Just over a week ago there was a mass overdose of medication sold by responsible companies like Boots. [I'm pleased to say, since this post, Boots has stopped making homeopathic remedies, though they currently still sell a handful of products.] Across the world people took vastly more than the recommended dose. And nothing happened. The reason? They were overdosing on homeopathic medicine.

The campaign was known as 10:23. The strange numbering refers to Avogadro's number. This is a number that delights chemists - it's the number of atoms in a mole of a substance. The actual number is around 6x1023, where 1023 is 1 with 23 zeroes after it. The reason this is of relevence to homeopathic medicine becomes clear when you realize how these medications are made.

The idea of homeopathy, which has no scientific basis whatsoever, is that you treat an ailment with a poison that produces a similiar effect. But to avoid finishing off your patients, you dilute that poison with water. In fact you dilute it over and over again, so much so, that you have reduced it by more than Avagadro's number. The chances are there is not a single molecule of the poison left - it's all water. You then drip the water onto a sugar pill, and that's your homeopathic remedy.

When homeopathy was first devised this wasn't a problem, as no one knew about atoms or Avogadro's number, but now we do, homeopaths have had to devise a reason for the medicine to work. They say it's because during the dilution process they bash the container against a leather strap, and this, in some mysterious way, enables the water to have a memory of the poison even after it has entirely gone. (You couldn't make this stuff up.)

So homeopathic remedies are sugar pills with no active ingredient, and all the evidence is that the positive results some people ascribe to homeopathy are down to the placebo effect. I was very careful not to say 'only the placebo effect', because placebos can really deliver results, particularly on the supression of pain. A good example is the internal mammary artery ligation operation. This used to be regularly performed to reduce chest pain as a result of angina.

It was an invasive procedure involving opening the chest and tying off the artery. Pain was reduced for a number of months. But in the 1950s, a surgeon tried a series of placebo operations. As far as the patients were concerned, they were undergoing the procedure, but in fact the surgeon just made an incision and closed up again. The result was exactly the same. The pain relief was not due to the operation, but to the natural painkillers released by the body when the brain assumed there would be pain relief - it was a placebo.

This same thing can happen with homeopathic remedies, to the real benefit of patients. But there is no active ingredient causing the outcome. While it's clearly totally unacceptable for homeopathy to be used for anything life threatening in place of real medicine, there's a difficult moral decision when it comes to, for instance, pain relief. Is it acceptable to lie to someone in order to make them feel better? We certainly do this all the time, but most would argue it's unprofessional to do this for medical reasons. And hence the 10:23 protest.

You will almost certainly have heard people say 'Yes, but there is scientific validation of homeopathy. It has been tested.' I'm afraid there is some misleading information floating about. See this article on the misrepresentation of scientific evidence on homeopathy to a House of Commons committee.

The sad thing is that most homeopaths won't accept reality and continue to insist that their medications do have a non-placebo effect. I want to leave you with a quote from a homeopathist in response to the 10:23 protest. Try not to fall off your chair.

Of course homeopaths know that one dose of however many pills taken together in one go, is the equivalent of only one dose, because it is the time frame that counts. So if they had repeatedly taken a dose every hour for the rest of the day, the skeptics would most certainly have felt the effects. Therefore this little stunt ‘proves’ little, although I wouldn’t be surprised if some of them sheepishly confess that they did experience some symptoms later, because after taking a homeopathic remedy, especially 30c or above, the effects can be felt for days afterwards.

'It's the time frame that counts.' Oh, that'll be okay, then. Sigh.

Five years later, I had some fascinating responses to another item I wrote:

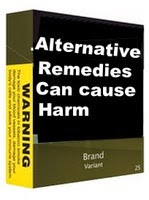

A couple of weeks ago I put up a blog item on Huffington Post, suggesting that it would be a good idea if alternative remedies, like cigarette packets, had to carry a health warning.

In some cases this was because there were reports of a high percentage of herbal remedies not containing the requisite herb, and sometimes containing fairly dubious contents that could be harmful. And in others, such as homeopathy, it was more because there was a danger of using a homeopathic remedy, and as a result not taking medication that actually does something. So I suggested a suitable warning for a homeopathic product might be something like:

WARNING -- contains no active ingredients. If taken in place of medical treatment could result in harm or deathNow it would be disingenuous of me to suggest that I didn't expect a certain amount of negative response. I was sure it would bring the homeopathy supporters out of the woodwork and it has. I'll go into some of the specific kinds of response in a moment, but the thing I was really quite surprised by (but probably shouldn't have been) was how close some of these responses were to someone defending their religious faith.

In a contentious area of science, there will be arguments. So, for instance, if I were to say that I rather hope MOND (modified Newtonian dynamics) can be made to work rather than particle dark matter as an explanation of the gravitational effects blamed on dark matter (which is true), I could sensibly expect cosmologists/astrophysicists to weigh in with the scientific arguments as to why dark matter is a better bet. But that's not what happened here at all. What I should have been seeing is a) a good explanation for the mechanism of homeopathy (as I claimed there wasn't one) and b) a good collection of large scale, double blinded trials undertaken by experienced professionals that came out in favour of homeopathy being more than a placebo effect. Neither of these things happened.

In practice, the science isn't contentious about homeopathy - it's very straight forward. And so, instead, arguments fell into these broad categories:

The report you mention only uses big studies - and this is a bad thing because? Good big studies give more statistically reliable results that good small studies - that's inevitable. If you don't understand this, take a statistics course, please.Making snide remarks - ad hominem attacks are the last resorts of those who have no good arguments. When I see things like 'Thanx [sic] for embarrassing yourself even more' and 'pointing out your egregious ignorance and prejudice in regard to the topic' I know I've hit a raw nerve: resorting to personal attacks means there clearly is a total inability to answer my two key points above.Attack allopathic [sic] medicine - there's a technical term for 'allopathic medicine': it's 'medicine'. However the real point here is that you can't defend something by attacking something else. (E.g. 'Rx drugs are toxic, and RCTs have proven that 50% of the drug trials cannot explain the method of action.') I know the huge amount of good done by modern medicine, and know plenty of people whose lives have been saved or improved by it. But even if every real doctor doing real medicine made all their patients worse, it wouldn't make alternative remedies any better. It's a bit like responding to a restaurant critic who says the food in your restaurant is bad by saying 'Yes, but the food in McDonald's is really bad.' So?It was also fascinating that at least four of the comments were by the same person, someone called Dana Ullman who strangely enough, according to Google is a 'proponent in [sic] the field of homeopathy. Ullman received his MPH from the University of California at Berkeley, and has since taught homeopathy and integrative health care.' So he's not at all biassed, unlike me, as I don't make any money from either alternative remedies or real medicine.

The sad thing is that in all those comments, none of the supporters of homeopathy could address my two key points (or even tried - randomly mentioning the existence of trials without citing them, when meta-studies like the Australian government one have a very clear outcome is not trying). And none seemed to actually realise the point is not that we need a warning that homeopathic remedies (unlike some other alternative therapies) can harm you, but that using them instead of things that work to treat dangerous diseases (there are homeopathic remedies for malaria, for instance, one of the world's biggest killer diseases) really does put people's lives and health at risk.

In the end, as I mentioned above, these weren't logical or scientific arguments I was presented with but rather statements of faith. And that should be a bit embarrassing for those concerned.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereNovember 29, 2024

A murderous time of year

Most of my book reviews are either science or science fiction. But December tends to be a month when I stray more into a different genre: somehow murder and Christmas make excellent bedfellows.

Most of my book reviews are either science or science fiction. But December tends to be a month when I stray more into a different genre: somehow murder and Christmas make excellent bedfellows. I know this doesn't work for everyone - I'm reminded of Paul F.'s kind words when using the link below to buy me a coffee 'I enjoy your reviews, particularly those areas in which I'm interested. 🙂'

I hope that many of you will enjoy the increased number of murderous reviews (there will still be some science/SF articles) - but if it's not your thing, I can reassure you that normal service will be renewed in the New Year... and have a great December, however you celebrate (or don't).Image by Girl with red hat from Unsplash.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereNovember 15, 2024

Sometimes you need to let go

When you really get engaged in a scientific theory, just as when you support a particular political viewpoint, it can be very difficult to let go. This might run counter to the theoretical nature of science, which supposedly delights in overturning old theories - but the reality is that scientists are human beings and don't like to change deeply held views.

When you really get engaged in a scientific theory, just as when you support a particular political viewpoint, it can be very difficult to let go. This might run counter to the theoretical nature of science, which supposedly delights in overturning old theories - but the reality is that scientists are human beings and don't like to change deeply held views.This need to sometimes push through a major change of viewpoint is behind Kuhn's concept of a paradigm shift - for a considerable time the old guard cling onto their theory until it become untenable and suddenly the consensus undergoes a heavy duty shift, which can be distressing to those left behind.

It happened to me, not as a scientist but as a young science enthusiast, when my passionate support for Fred Hoyle and the steady state theory had to be swept aside for the Big Bang theory. Now, it's entirely possible that something similar is happening to upset the equilibrium of supporters of the existence of dark matter particles.

There is no doubt at all that there is an effect, resulting galaxies not being under gravity as expected and that is commonly assumed to be due to dark matter. But the particles have stubbornly failed to turn up in experiment after experiment. There are alternative theories based on modified gravity: the original, MOND or MOdified Newtonian Dynamics, has some issues, but arguably fewer than those arising from attempts to explain the effect with massive particles that don't interact electromagnetically.

The Big Bang triumphed when evidence came to light that the early universe was very different to the way it is now. It may be that a similar failure of expectation of the early universe will do for dark matter particles, as it has turned out, thanks to new data from the James Webb Space Telescope, that there were massive galaxies in the early universe - something predicted by modified gravity theories, but not by dark matter particle theories.

Of course, we could still discover dark matter - but this is certainly a major blow. To find more details on this, please take a look at this summary in Stacy McGaugh's excellent Triton Station blog.

Image by Alexander Andrews from Unsplash - it's not directly relevant, but it's pretty...These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here