Marc Hartzman's Blog, page 2

November 18, 2024

Cults, Cryptids, and Cursed Objects: One Quirk Author Interviews Another

J.W. Ocker and I are both authors at Quirk Books. We share an editor and we share a love of the strange and usual. I’ve written about Martians, ghosts and UFOs and he’s about cursed objects, cryptids, and cults. On the side, I run this site, Weird Historian, while Ocker runs Odd Things I’ve Seen. We even both maintain day jobs in advertising. So I figured our weird worlds should come together for an interview, which is transcribed below.

If you follow Ocker on social media, you’ve surely seen photos of his frequent travels to odd places (to see odd things) with his kids—which is where our conversation begins.

Among J.W. Ocker’s titles are these three published by Quirk Books.

Among J.W. Ocker’s titles are these three published by Quirk Books.WH: It’s great to chat with you—your books are wonderful, and it’s clear you have a blast writing them. I see you post a lot of photos of you with your kids during your travels for research and it looks like they’re loving it. Do they enjoy going on these journeys with you? And what do they think of your books?

JWO: They’re so into it. They love the books. So this is probably the best thing about writing for me. When my mom died in 2016, that was the first time I ever faced mortality, thinking what the hell am I doing with my life? And what I landed on is, at the end of the day, I’m creating stuff for my children. It’s kind of become their identity as well. My kids range in age from six to 14, and when they were very young it was hard. They didn’t like being in the car a lot. They got sick, whatever. As they’re growing older, they’re almost liking it more than I do. We’re going to the Pine Barrens this weekend just because the girls found out about The Jersey Devil, got obsessed, and now they want to go see the Pine Barrens. So, like, it’s not even my trip. One of my daughters has cryptid stuff all over her walls. I have three kids books out and they’re always reading those and bringing them to school. They want me to come do talks. So it’s become this amazing bonding situation that’s alien to me, because I didn’t have this with my parents at all. I still don’t know what my dad did most of the time for a living. Something vaguely electronics, or something that, but like, this is real bonding. We talk about the books, we talk about going places.

When we go see something, I need to take a picture of it with myself, because that’s my gig, right? Odd Things I’ve Seen and I’ve been taking selfies since before selfies were a thing I said to use, like tripods and digital cameras and stuff. And now those group shots are literally those girls pushing their way into the frame. It’s been amazing. My family fell into hard times a couple years ago: divorce, death, stuff like that. So bringing my girls along on these trips has become the most fulfilling part of writing these books. They can be a part of it, they can be the first to read the manuscript, all that kind of stuff. The most important part is that relationship.

J.W. Ocker with his daughters at the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in West Virginia.

J.W. Ocker with his daughters at the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in West Virginia.WH: I love that. I’ve been writing about sideshow performers for a long time, so we know a lot of unusual people who are friends now. My kids grew up around a lot of performers in that community: sword swallowers, fire eaters, a knife thrower. They’ve even fed two-headed turtles. When my older daughter wrote her college essay—she didn’t let me read it until after she got accepted—she started off by talking about meeting all these people who did these amazing things, who did the impossible. And then she spun that into if they could do the impossible, why couldn’t she do the impossible? Her impossible wasn’t sideshow, it was challenges she’s had to deal with and overcome in life. I love that these experiences left a powerful impression.

JWO: Yeah, it’s great. I tell my kids, you want to find the people who are interesting and make those your friends. Those the people you want around you inspiring you. A lot of people are boring. Ignore those people. Find the people who are different, because they’re gonna be much more rewarding friendships in the end.

WH: Absolutely. Well, let’s go back a little bit. What first got you into oddities, and what point did you start writing about them?

JWO: That’s a pretty clear line for me, because I grew up hyper-religious and in a very small fish bowl and not very plugged into pop culture. And then I found myself in maybe 2004 or 2005, I was in this tiny, dumpy apartment in Brunswick, Maryland, right on the train line. I’d already graduated from college and already earned my master’s, and I was depressed. I was alone. I had no girlfriend, no friends. I was kind of like, not suicidal, but depressed, so that you’re thinking about what would it be like not to exist anymore. And I thought, ‘Oh, man, I’ve done nothing.’ I vaguely knew I wanted to be a writer, but I wasn’t writing. I needed to write something, but I literally had nothing to write about. I was a boring dude in a boring situation with no ideas, and at the time, there were a few shows out and a few books out that got me into oddities. I realized, if I were to write about something, if I want to be interesting enough to write about stuff, I need to find the interesting thing. So if I can find something weird and write about that, I can be boring. It’s okay if I’m boring, if I’m writing about an interesting thing. And so I just started jumping in my car and driving to nearby things. I would drive an hour away, and then I would drive two hours away, and then every weekend, I would go longer and farther, and then I started a website. That’s kind of what happened—a blogger.com, website, where I’d chronicle these weird places I would drive to. And then that’s what blew up for me and gave me the book opportunities. It was like boredom and depression and realizing that there’s nothing much to you, so go find cool stuff elsewhere, you know. It was literally just a survival mechanism.

WH: What was that first weird place you drove to?

JWO: The town I lived in, Brunswick, was the next town over from Burkittsville, Maryland, which is where Blair Witch takes place and was filmed. So I went over there and I took pictures of the cemetery—I was a big horror fan already at that point and I wanted to visit more horror filming sites. So that was the first one, then the five I launched my website, OTIS [Odd Things I’ve Seen] was the Mothman statue in West Virginia, because, again, I was in the Mid Atlantic at the time, then a statue called The Awakening, which was this giant clawing his way out of the ground in DC at the time, then it was the Orson Welles memorial in Grovers Mill, New Jersey, and then it was strangely enough, the Great Pyramid of Giza, because I was working for an ocean technology magazine and just happened to get a free ride to Egypt to report on something over there. So Mid Atlantic sites is where I started.

J.W. Ocker visits the Mothman statue in Point Pleasant, West Virginia.

J.W. Ocker visits the Mothman statue in Point Pleasant, West Virginia.

WH: That’s a great start! How did it all lead to your first book?

JWO: The first book was The New England Grimpendium. At the time, the OTIS website caught on and got a bunch of followers. It was actually my second website—I started my first one in 2000 with a friend of mine, and I just fell in love with nonfiction writing at that point, because that’s the voice of the internet. It’s nonfiction, you could write whatever’s in your head. This was a nascent Internet, it didn’t matter. I could write a thousand words about this obscure episode of a sitcom or the Book of Job in the Bible. Nobody’s stopping you. You just hit “publish.” So when I started the new site, OTIS, about seven years later, I had one guy contact me and say, “Hey, this could be a book project. I don’t want to be your agent, I just want to pitch this one project to one publisher.” It didn’t work out because it was scattered, there was no theme. It was just what I found odd or whatever and that I could personally get to. That’s kind of a constraint. So at that point, I was starting a new life and I’d always wanted to live in New England. I finally got a job opportunity there so I moved with my fiancée at the time. Almost the second I landed in New England I had this giant list of odd things I wanted to see. New England’s full of the stuff. And at that point I realized New England is an angle. Random oddities that I’ve seen is not an angle for a book, but New England oddities are a very specific angle. So I put together a pitch for New England literary sites and another pitch for New England death-related sites and I sent them off to one local publisher. I figured a local New England publisher will publish the New England book. It was called Countryman Press in Vermont. Turns out they were local, but they were owned by W.W. Norton in Manhattan. I had no idea. They didn’t like the literary sites idea, but they loved the death-related sites idea, and that was it. I spent the next six months driving 7,000 miles around New England seeing all these sites I wanted to see and then writing about them.

WH: The book truly becomes an adventure.

Another odd thing J.W. Ocker has seen: The Awakening sculpture.

Another odd thing J.W. Ocker has seen: The Awakening sculpture.JWO: I consider my nonfiction almost biographical. I always tell people having a nonfiction book at the end of a project is just a cherry—the experience is way more worth it, seeing cool things, getting access to cool things, I have friends from some of these projects.

WH: I totally agree! Let’s fast forward to your latest book, Cult Following: The Extreme Sects That Capture Our Imaginations―and Take Over Our Lives, from Quirk. What was it like to dive into that world? Cults seem like a scarier place than the worlds of cryptids or cursed objects. How did you approach it?

JWO: It was purposefully chosen for that reason, because it was a little bit different. Now, in a way, it’s been a vein I’ve always been interested in. When I go see oddities, cult sites are part of it. I’ve been to cult communes before, I’ve been to the Jonestown mass grave in Oakland, and I’ve been to the Koreshan Commune in Estero, Florida. So I was always interested in cults as a pillar of oddity. But there were two reasons why I pitched this book. One was because I came out of a very, very, very, very conservative sect of religion. So those kinds of religions interest me as a result. But the other thing is, my style is very nonchalant and jokey, which fits well when you’re talking about Bigfoot or you’re talking about a cursed dresser drawer. That tone fits that. But when I talk about actual abuse and actual manipulations and actual tragedies, I wondered if I could still do that tight wire of treating the subject with respect, but also having fun with it, which is kind of like, I guess my angle for all stuff. Can I do that with really horrible situations? And that was the challenge I wanted to chase. Can I write about the Ant Hill Kids and people getting their arms staple-gunned to a table and all those unanesthetized surgeries, and those kinds of things? Could I do that but still keep my tone? Would I lose my voice if I wrote about that? And I think it worked. I write about true crime a lot, for instance. I’ve been to all the sites related to Boston Strangler and Jack the Ripper, and I’ve been able to deal with that without treating it lightly or disrespectfully, but still treating it with wonder. To me, horror is a type of wonder—the reason why awesome and awful are very much related. It’s shocking and awful that a human person can do these things, but it’s still a type of wonder. So that was the motivation on that book. But you’re right. It’s a very different book from Cryptids, Cursed Objects, Edgar Allan Poe, Salem, my usual shtick.

WH: I thought you did a great job keeping your voice. There’s so many sad, tragic things, but some of it is also just so ridiculous that it opens the door to inject a little playfulness in the tone.

JWO: It is ridiculous. Usually with my books I’m trying to find some insight that’s not normal. The one I found for Cults is that as weird as cults are, and as shocking—you always wonder how rational people join cults—it turns out it’s the most human thing to do on the planet. You know, a bunch of people joining together under a single cause, behind an impressive leader. Literally, that’s life, that’s family, that’s corporations, that’s politics, society, towns. So in some ways, joining a cult is the most human thing you can do, and once you kind of realize that, a) empathy helps, but b), it’s even more terrifying. If it’s the most natural thing we can do, and that natural thing almost always ends in abuse and tragedy, that fits my cynicism. It was a harder book to write than anything I’ve ever written before, because in some ways, it’s a mainstream topic, unlike my other books, which means there’s a ton of source material. I’ve gotta write 2,000 words about the Manson family? It’s impossible. Writing 200,000 words about the Manson family is very possible, but writing only 2,000 words about him is hard and again, all my sources are legitimate. Manson has Time magazines, newspapers, entire books written by the people who were involved, as opposed to, like, cryptids, where you’re digging through newspaper accounts and it’s a different style of research. It is the most mainstream thing I’ve done, I think, of all my works.

WH: I know what you mean by all that, too. There’s almost too much information. For my next Quirk book, You’re Not Supposed to Know About This, one of the sections is on the Manhattan Project, which was daunting because there’s just so much there. What do I cover? What don’t I cover? I mean, the biography on Oppenheimer that became the movie is like 800 pages or something. That’s just one source. So yeah, the challenge is how do I boil this down and make sure it’s interesting?

JWO: It’s why I’m finding this new book [Don’t Go There] to be so easy in comparison. Because even the Bermuda Triangle, which sounds like it’s a giant topic, is not that giant of a topic. The sources that cover it are mostly illegitimate, with just a few legitimate ones. But it’s so much easier than real life, true crime, or in your case, real historical events.

The story of the triangle is literally stuff disappears in the ocean. There’s tons of theories but there’s no stories on the theories. It’s not like there’s survivors that saw a shaft of light or other time zones. It’s literally things disappeared in an ocean. So the story for me is the story of how it became the most famous paranormal spot on the planet. How did that happen? That’s where I had to go, because if I just told the story of the triangle, it was just these planes disappeared and then this ship disappeared…

WH: That sounds like a fun story to be diving into though.

JWO: So much fun. Way more fun than cults.

WH: Diving back into cults briefly, was there one that stood out as more disturbing than the others?

JWO: You kind of get immune to it, like anytime there’s sex trafficking or sex abuse that was so common, you kind of got immune to that. But the one that really took me down was the Ant Hill Kids, which is a Canadian cult run by Roch Thériault. He was so brutal to his people. He would defile corpses and kill children and cut people open and pull people’s teeth out. But his cult started out as a clean-living cult. It was literally how to stop smoking and eat more vegan—something very, very benign. But as soon as he got power, and as soon as he isolated geographically up in the mountains of Canada, he just went off the deep end and the stuff he did was awful. As a male leader of a cult, he was inevitably gonna take every woman in the organization. One of his wives had her arm nailed to a table until it turned purple and they had to cut it off. And he burned her breasts and pulled her teeth out. And her quote, when he got finally busted and sent to jail was, “Yes, he did awful things, but normally he was a pretty nice guy.” That level of cognitive dissonance—that phrase came out of a cult actually—that cognitive dissonance was also very terrifying to me. This is such an extreme level, it was just sad and depressing. It was actually the first entry I wrote, because that was the test entry for me and my editor, Rebecca. I was like, all right, this is the worst thing I know of when I write about this thing. If it works, the cult book should work. If it doesn’t, it probably won’t. It’s probably not the project for me.

WH: That makes sense. Get the worst out of the way, which you did nicely. Let’s shift to the world of cryptids. Which creatures rise above the others in weirdness?

The Lizard Man, from Ocker’s book, The United States of Cryptids.

The Lizard Man, from Ocker’s book, The United States of Cryptids.JWO: The ones that I always loved the most are the ones that had outlandish stories that were documented in papers. So it wasn’t just somebody saw something and then they describe it. It’s vague and dark and hairy and whatever. A good one I love a lot is the Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp. This is the story of a boy who worked at McDonald’s—he was a teenager driving home late at night. Somewhere he got out of the car and then suddenly he got chased by this red-eyed reptilian creature. And the real story behind that is he gets home, there’s scratches on the car and his parents ask him why he’s late and about the car. And he tells him the story—and there’s probably two truths of it. One was that he just kind of wrecked the car up a little bit on the drive home and had to invent an excuse why. And then that excuse just caught on into a major myth, which I love—that idea of a teenager’s white lie to his parents turns into the story that the entire community grabs and it’s in the museums now and all those kinds of things. He also might have just gotten chased away by a local farmer who was very protective of his land. But I love this idea of either there’s a reptilian humanoid in this in the swamps of South Carolina, or it was a kid just trying to get out of getting in trouble with his parents. I love those two extremes.

WH: And no one applied Occam’s razor to those possibilities.

JWO: What I see happen often, especially in the crypto world and in the paranormal too, is what I call reverse Occam’s razor, where, if the simple answer doesn’t pan out, then go weirder. So Bigfoot—we’re at Year 75 with no Bigfoot body. Now people are like, what if he’s a ghost? What if he’s an extra-dimensional visitor? What if he’s the pet of an alien? Because, again, the simplest answer, he doesn’t exist, is not fun for them. So they go weirder. They find theories that you can’t disprove at all. You can’t disprove that something is an extraterrestrial or an extra-dimensional visitor, right? You just can’t disprove that.

WH: Gotta keep that thing alive no matter what.

JWO: Yeah, no matter what. They literally can’t say, “Oh, I guess there’s no Bigfoot.” That’s just too destructive to their psyches, right? You see it in cults and religion too, they do the same thing where they have to get weirder and weirder because it’s so easy to disprove certain tenets, you know? So they have to get to a place where it’s impossible to disprove and impossible to prove, and then it’s just a matter of faith. And you can’t argue faith. It’s a very human thing to do.

WH: I always love the stories of Spiritualist mediums getting caught faking something, and then their supporters say they faked it that time because they can’t perform perfectly all the time, and they have to put on a show. But, they’d say, other times are real.

JWO: That’s exactly what happened with breatharianism. The head guy got caught coming out of a 7-Eleven with a Twinkie. And they were like, yes, he’s a fraud, but his ideas are not fraudulent. Again, we’ve got cognitive dissonance. I love that example. In the epilogue to Cult Following, I have seven things that all cults seem to have in common, and one of them is you need a revelation that you know hasn’t been around for thousands of years, things that I’ve never heard in my life—a real revelation. And breatharianism falls in that category for me. Somebody tells me, “You know what, eating is a fraud. You never have to eat.” To me, that shakes reality. Reality trembles a little bit. If true, that is the most amazing revelation I’ve ever heard.

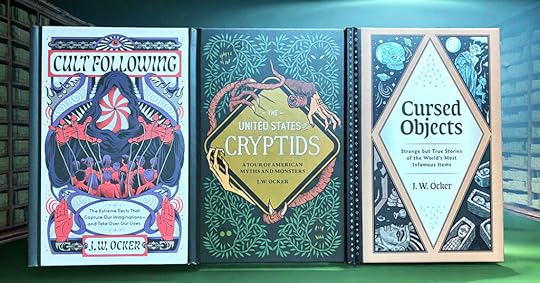

Muncie Evening Press, October 7, 1993.

Muncie Evening Press, October 7, 1993.WH: Plus, it’s a great money saver and you get a lot of time back.

JWO: Yes, we have a fraught relationship with food. We take that line out of our budget and we’re all rich. Or the anxiety of losing weight and gaining weight, that’s gone too! It serves a definite psychological need that we have. In fact, I met somebody—this was actually scary—my first talk about Cult Following was at this Barnes & Noble in Connecticut and they asked me questions at the end. I brought up breatharianism, because I will never not bring it up for the rest of my life, and this kid who was probably twenty-five and skinny, said, “Oh, I know about that group.” I said, “Yeah, it’s crazy, right?” He said, “Well, I’ve been trying to research it, because what if it’s true? I’m trying to save money.” He was dead serious. He was researching this on YouTube (of course) because he thought it would be a good way to save money. I guess he was probably having trouble making ends meet and it appealed to that one sense of saving money. So it doesn’t matter if it’s false or weird or sounds bizarre.

WH: You’d think eventually the starvation would be a real downside. One last question. When I’m doing interviews about my books, I’m always asked if I’ve seen a UFO or a ghost. Do you get that as well? Questions about seeing strange creatures or encountering haunted objects?

JWO: All the time. I do talks with ghost hunters and I have to give them a boring answer. I have to tell them, you know, no, I don’t believe in any of this stuff. But I tell them I’m a cynic, and I don’t believe in anything from true love to ghosts—like the entire gamut. But I also tell them that, there’s a few caveats. One is when I say I’ve never had an experience, I do believe we’re all one experience away from believing anything on the planet for sure, but I tell them I’m a guy who has spent nights in abandoned prisons and asylums and cemeteries and murder scenes—I’ve done that, I’ve done the work—and I still don’t have a single story about it, or cryptids. Once upon a time when I was a Christian, I believed in everything, witches and ghosts and demons, and gods and I actually believed tons of stuff. So I know about the elasticity of belief. And this is where I’ll end it, so I’m not being too judgmental, because I just have never had an experience that convinces me. And of all the people on the planet, I should have. I’m looking for it. I’m definitely the “I Want to Believe” poster in Mulder’s office, but everywhere I go, nothing convinces me.

Find out more about the odd things J.W. Ocker has seen—and written about—at Odd Things I’ve Seen and at Quirk Books. Purchase his books at either site, or wherever you buy books. Reading about cults is way better than joining one.

<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post Cults, Cryptids, and Cursed Objects: One Quirk Author Interviews Another appeared first on Weird Historian.

November 15, 2024

The Phantom Barber of Pascagoula Strikes Fear into Innocent Follicles

In June of 1942, while World War II raged with unimaginable horrors, the small town of Pascagoula, Mississippi, faced a far different type of terror. A criminal prowled its streets at night and snuck into people’s homes—not to steal money or other valuables, but to steal hair. Known as the Phantom Barber, this follicle fiend would break into homes and cut the hair of young girls.

In one instance, the intruder entered a convent and cut locks from three girls. One of them woke as he was slipping out the window and only caught a glimpse. “He was sorta short, sorta fat, and he was wearing a white sweatshirt,” she told authorities.

Article from the Detroit Evening Times, August 30, 1942.

Article from the Detroit Evening Times, August 30, 1942.As the strange snippings continued, the police put their bloodhounds on the case and offered a $300 reward for his capture (nearly $6,000 today). In addition to putting the department on alert, six volunteer officers were given guns to help catch the perpetrator. Parents nailed windows shut and began sleeping with their children to protect their precious tresses.

No knew why someone would go to such lengths to snatch clumps of hair, though some speculated it was being used in “back country ‘hex’ ceremonies.”

Within a few months, after at least seven more nocturnal haircuts, police, with the help of a Pinkerton detective, apprehended William A. Dolan, a 57-year-old German chemist. According to the Pascagoula police chief, the barber was a Nazi sympathizer who wanted to strike at the morale of American workers helping with the war effort.

Though Dolan’s barbaric barbering left no one physically injured, a vicious attack with an iron rod on a married couple that summer led to an attempted murder charge. Hair trimmings and shears were found in his backyard. Dolan denied any wrong doings, but by November he was found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison. Finally, the people of Pascagoula could sleep at night without worrying about waking up with a bad haircut.

<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post The Phantom Barber of Pascagoula Strikes Fear into Innocent Follicles appeared first on Weird Historian.

October 9, 2024

An Interview with a Horror Historian: Jeremy Dauber, Author of “American Scary”

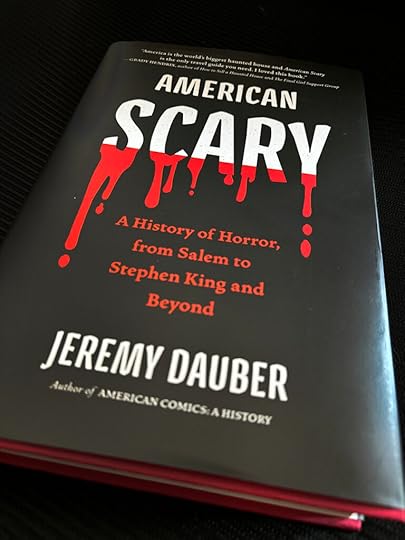

American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond, by Jeremy Dauber (Algonquin Books/Hachette)

American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond, by Jeremy Dauber (Algonquin Books/Hachette)It’s Halloween season. But whether it’s October or any other month, what is it that causes us to invite fear into our minds? To welcome the slashers, zombies, vampires, ghosts, creepy creatures, and crazy people that fill our favorite horror movies and scary stories? Author Jeremy Dauber, a professor of Jewish literature and American studies at Columbia University, brilliantly dissects the history of American horror in his new true treasure trove of terror, American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond (Algonquin Books/Hachette).

The book delves into the way horror has evolved over four American centuries, reflecting society from the colonial era to the present and showing how many of our fears have held constant. I spoke with Dauber about the phenomenon of horror and several of his personal favorites. Our conversation follows:

Weird Historian: There’s a whole lot packed into this book! How long has it been in the making? Is this just the culmination of a lifetime of watching movies, reading books and watching TV, or is it something you of dove into for the purpose of the book?

Jeremy Dauber: Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been interested in certain parts of the horror experience, trying to figure out what I was willing to read or watch and not be too scared about, and trying to figure out why I like it. I was a big Stephen King fan from early on, and I got into horror comics and things like that, but then I started teaching about it and decided, okay, I can write about this. And then the last few years have been a much more intensive immersion in both stuff that I had never seen before because I was too scared, or stuff that I had seen. But it had been a while, and was thinking about it with new eyes, so to speak.

WH: Yeah, that makes sense. You have to look at it fresh and with a new lens. What is it about horror that fascinates you so, so specifically?

JD: One of the main things that I found so interesting about it is that it really is a kind of X ray into a society. If you’re really trying to understand what makes a particular society, a particular culture tick, one of the best ways—not the only way—but one of the best ways of doing it, is to find out what scares them. And so looking at what really unsettles or disturbs or makes a country’s culture anxious is an interesting way to see what’s troubling them and what’s making them tick. So that was a lot of what really drew me to it as a subject of both studying and writing a story about it, and some of it was just that I really feel like there are very few kinds of works of art that really established such a visceral connection with their audience. You can go see an amazing painting and you’re going to be moved, and you can listen to a poem, but horror is one of those things that really elicits an involuntary reaction from you. That’s how powerful it is, right? I mean, you scream, or you jump, or you gasp, and investigating that kind of power was also something that was fun to do.

WH: It does really stick with you more, doesn’t it? If you’re scared, the reaction lingers more than feeling moved by a poem, for example, right?

JD: I agree with that. There are certainly poems that you come back to, they’re something you think about that really can change your life, so I’m not down on poems—of course, there’s scary poems, too—but there are ways in which you are watching a movie and then it literally haunts you. Let’s use that horror word, right? I mean, you can come back and you’re like, “Well, I know it’s not real, but on the other hand, I’m still going to check under the bed. I’m still going to kind of look at the closet before I go to bed.” Even if nobody’s around, or maybe especially if nobody’s around. And I think that sometimes that speaks to just the way in which horror activates these universal fears in all of us, and sometimes it’s about particular things that are going on in society now that that movie or that book are really pointing at and prodding at.

WH: It is a reflection in a lot of ways. You included Black Mirror in your book, which, to me, is the only thing that’s come close to The Twilight Zone in terms of that genre. It’s so well done, but that’s truly reflecting on right now—like a peek 10 minutes into the future.

JD: That’s right. A lot of horror is about technology, whatever period that technology is new in, there’s horror. And when you’re telling the story of America, you have horror of the new industrial machines, right? That’s new. You have horror of the new anonymity of cities, and then horror of the atomic bomb, right? You have horror of space exploration. All of these things allow for new kinds of ways of being afraid. But in that sense, they’re also continuous, because there’s always something new, and we’re always afraid of it. But I think you’re right, Black Mirror does a great job of taking the horror of our particular moment, these phone screens, these things we carry around our pockets, these algorithms, it’s a great articulation of those particular new technological fears.

WH: Yeah, it’s very much right now. Do you have an opinion on what the best decade for horror was?

JD: That’s a great question. I generally say that there’s the cyclical kind of quality, let’s say—so I think this is cheating a little bit—but I love the ‘30s, the ‘50s, the ‘70s into the ‘80s, and\ the last 10 years or so, which have been amazing. I think, given sort of my own interests in predilections, I like the ‘50s movies in some ways the most. But that’s just my own personal taste. I think movies from the ‘70s and movies now are just incredible. They’re just amazing.

WH: My next question was going to be about the recent movies. There’s been quite a resurgence in the genre within the last 10 to 15 years or so. What’s led to it, and do you have any particular ones that stand out the most for you?

JD: Well, I’ll tell you a little story. I am of an age where I went to see The Blair Witch Project, which is from 1999, in the movie theaters. So, right before this period starts. And I went to see it in this rundown movie theater, and I was the only person in the theater, like the single only person in this big theater that was kind of broken down. It was a horror venue itself, right? And I was just overwhelmed and paralyzed with fear. So The Blair Witch Project really stamped the beginning. Another phenomenal movie that was a doorway to this new period was The Sixth Sense, which comes out the same year. I saw it in a big crowd, and it was a great movie, it’s a phenomenal movie, but, but it didn’t have that same effect. But one of the things about The Blair Witch Project is it’s the found footage genre. It’s this bunch of student filmmakers who can carry around a camera and do stuff in a lo-fi way. Obviously, that’s the movie within the movie. But it also speaks to the idea that lots of people can make horror movies now. They don’t have to necessarily go through the studios. They can post things online. They can do them much more cheaply. The equipment is cheaper, it’s easier to operate. And so you really have the opportunity of letting a thousand flowers of more individual sensibilities bloom. Also, at the same time, you have these people who, thanks to the internet and before that, DVDs and video stores, are easily able to see so much more than people of previous generations ever were. So they’re really able to become horror aficionados in a way that was very, very difficult for other people. So they have the raw input, and then they have the kind of idiosyncratic creativity, and then they have the places to put them.

Copyright 1955 United Artists Corp, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Copyright 1955 United Artists Corp, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsWH: Very true. Throughout the decades you’ve mentioned, do you have an all-time favorite horror film and/or novel?

JD: Thank you for bringing up both, because I think there’s so much great literature as well as so many great movies. So what I think my favorite horror movie is, it sometimes depends on the day, and the mood that I’m in, but I think the movie that’s the most American horror movie, the one that says the most about America, in some ways, is that 1950s movie The Night of the Hunter, which, for people who don’t know, it’s this movie that’s based on a novel, which is based on a true crime story about what we might call a lonely hearts killer. Somebody who marries women and then kills them. And the movie is set during the Great Depression. And this particular lonely hearts killer, who is played by Robert Mitchum, is a psychopathic preacher, who’s also trying to get this treasure that he knows is somewhere on the premises. It is the combination of a dark fairy tale with a genuinely terrifying main character, and a real exploration of what the dark side of the American existence is. Every time I see it, I’m just amazed at how good it is. That, to me is the most American movie, and on most given days, it’s probably my favorite. And if you haven’t watched it out there. I envy your first watch of it. I really think it’s just tremendous.

In terms of my favorite horror novel, you know, I gotta say it’s this is not so surprising, perhaps, given the early traumas of my upbringing: it’s a Stephen King novel. And this one also shifts from day to day, but I recently reread It, and I actually do think that it is his great work. It says everything it needs to about childhood in America, and what it means to be afraid in America. I just love it. If you’ve only seen the movie, go back and read the book. It’s only 1,100 pages.

WH: One last thing, because this is Weird Historian, what is your favorite all-time horror film in the category of weirdest?

JD: Oh, weirdest. That’s a great question. So the weirdest horror movie that is coming to my mind—something that we would all recognize as horror—is probably Two Thousand Maniacs! Have you seen that?

WH: No.

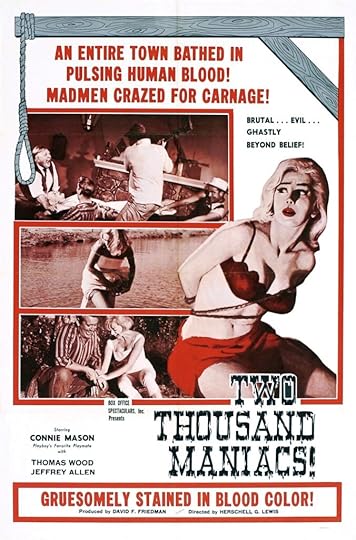

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964)

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964)JD: So Two Thousand Maniacs! is made by this guy who is considered an early pioneer in gore. And basically what the movie is is it’s sort of like Brigadoon, but with a psychopathic, bloody set of murders. So it’s this southern town that appears from 1964 that has been totally slaughtered by the Union during the Civil War. They disappear for 100 years, then they come back and they kill any unwary northern travelers who come in their way. And it is weird and bonkers and incredibly gory, and also has some very interesting things to say about that prime period of the civil rights movement in the south, of this very, sort of complicated resentment between the north and south. It’s a town full of ghosts, and they’re murderous, so it’s really interesting in that way.

The weirdest movie that pokes fear in the American public is a movie by John Waters called Pink Flamingos, which is maybe the most disturbing American movie ever made, bar none, right?

WH: Definitely a weird one.

JD: It’s a weird one, and it is not for the faint of heart or stomach. I would not necessarily recommend it, and it’s not because it is scary, but it really is just a challenge to everything about society in these extremely anxiety producing and alienating ways. So that’s certainly weird. No question about that.

WH: Agreed! American Scary is an amazing book, so thank you for putting it together. I wish you the best of luck with it.

So, what’s your favorite horror movie and book? Mine are The Changeling (1979) and Bram Stoker’s classic, Dracula. Whatever yours are, pick up American Scary, and you just might discover a few dozen more favorites.

<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post An Interview with a Horror Historian: Jeremy Dauber, Author of “American Scary” appeared first on Weird Historian.

September 28, 2024

The Ouija Board Told Her to Kill, She Listened

In the late 1800s, Ouija boards gained popularity as a more efficient way for a planchette to spell out messages from the dead. Mediums could deliver more spirit communications at séances and some even wrote books guided by the ghosts of authors, including Mark Twain. And while the ouija board was generally viewed as harmless until The Exorcist portrayed it as a conduit for evil in 1973, it had taken a truly dark turn decades earlier. One that led to a shooting.

The incident took place in December 1933, after a Ouija board in Arizona allegedly told 15-year-old Mattie Turley to kill her father so her mother could hitch herself to a “young cowboy.”

“Mother told me that Ouija board could not denied, and that I would not even be arrested for doing it,” the teenager testified.

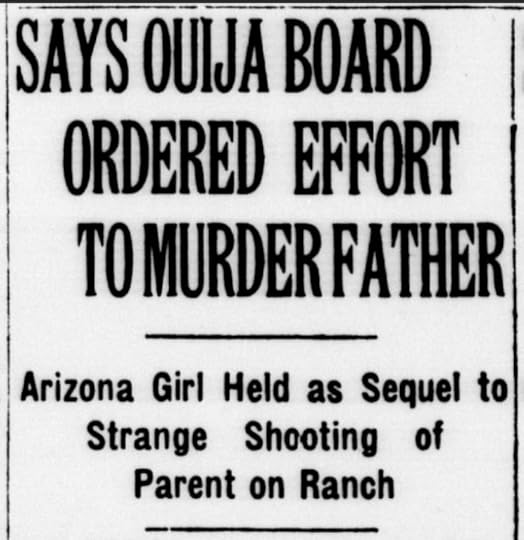

The Bismarck Tribune, December 22, 1933.

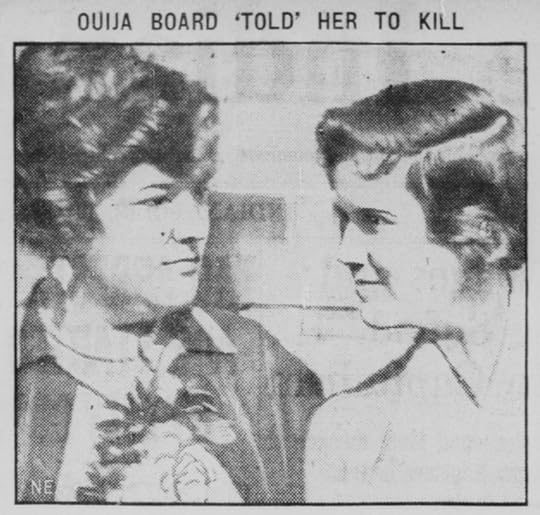

The Bismarck Tribune, December 22, 1933. The Indianapolis Times, January 4, 1934.

The Indianapolis Times, January 4, 1934.The Ouija board apparently had been in cahoots with Dorothea Turley, a former beauty queen, before the shooting. An earlier consultation gave her the location of buried treasure. Prior to getting shot, Ernest J. Turley had busily “blasted away rock in search of the treasure” to please his wife—while she got busy with her cowboy beau. Their daughter explained that following the fruitless treasure hunt affair, the board was consulted again, at which point “it wrote out I was to kill my father.”

For pulling the trigger, Mattie was sent to the state school for delinquent girls for six years. Dorothea, for instigating the murder attempt (spirit or no spirit), was given a 10- to 25-year sentence, but only served two years. Ernest survived his wounds.

For more on the history of the Ouija board and Mark Twain’s ghost writing from beyond the veil, check out Chasing Ghosts: A Tour of Our Fascination with Spirits and the Supernatural , written by Weird Historian Marc Hartzman, published by Quirk Books.

Chasing Ghosts by Marc Hartzman, published by Quirk Books.

Chasing Ghosts by Marc Hartzman, published by Quirk Books.<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post The Ouija Board Told Her to Kill, She Listened appeared first on Weird Historian.

September 12, 2024

Don’t Mess with the Not-So-Greatest Knife Thrower

I’ve known The Great Throwdini for about twenty years now, having first met him while writing American Sideshow. He’s often jokingly said, “Don’t mess with the knife thrower.” Good advice—a knife thrower is not someone you’d ever want to anger. In December 1950, a man named Raiffe Lilly learned this the hard way after goading a man who claimed to be “the greatest knife thrower in Mexico.”

Throwdini is the world’s fastest and most accurate knife thrower. The Mexican knife thrower, despite his claim, was not. And messing with an inaccurate knife thrower is an especially bad idea.

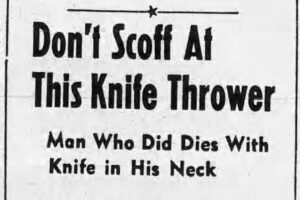

Headline from the Ada Evening News (Ada, Oklahoma), December 7, 1950.

Headline from the Ada Evening News (Ada, Oklahoma), December 7, 1950.Lilly was with his pals, John Hamer and Carl Strong, in a San Francisco hotel hallway when the knife thrower entered with a hunting knife in hand. Without being asked, he announced his claim to fame.

Amused, Hamer offered to stand against the wall and let the man prove his prowess. He missed by a few feet as the knife clanged off the wall.

After that debacle, Lilly opted to join in on the fun and gave the knife thrower a second chance. This time the knife missed again. A knife thrower throws around a target, not at the target. This knife struck Lilly right in the neck. The impaler rushed to his victim’s aid, pulled the knife out, then ran off.

Lilly did not survive.

Unlike the “greatest knife thrower in Mexico,” The Great Throwdini never hit his target girl. This performance took place in October 2010. Photo by Marc Hartzman.

Unlike the “greatest knife thrower in Mexico,” The Great Throwdini never hit his target girl. This performance took place in October 2010. Photo by Marc Hartzman.<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post Don’t Mess with the Not-So-Greatest Knife Thrower appeared first on Weird Historian.

August 28, 2024

“Atlas of Paranormal Places” Enlightens Dark Tourists

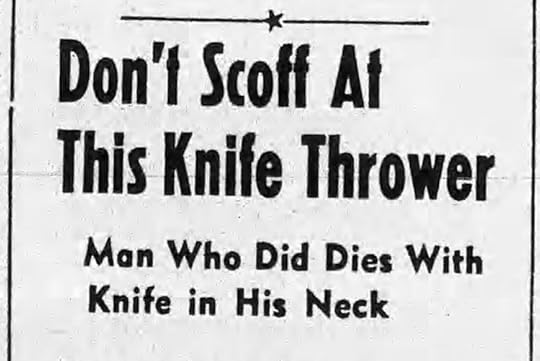

Atlas of Paranormal Places, by Evelyn Hollow (Ivy Press).

Atlas of Paranormal Places, by Evelyn Hollow (Ivy Press).Whenever I travel, I enjoy visiting the usual tourist spots, but I have a special fondness for discovering the odd, unusual, and lesser-known sights. The places with—as this website suggests—a weird history or dark past.

Several years ago, during a vacation in Italy, I made our bike tour guide in Rome take my family and me to the extraordinary crypts of the Capuchin friars beneath the church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini. The rooms feature ornate displays created from the bones of more than 4,000 capuchin monks lining the walls and vaulted ceilings. Several monks remain fully in tact with their robes. How is this not part of every bike tour?

If you, too, are curious about everything from haunted places and sacred sites to homes of cryptids and legends, Atlas of Paranormal Places: A Journey to the World’s Most Supernatural Places serves as an ideal guide.

In this beautifully crafted hardcover book, author Evelyn Hollow —an award-winning Scottish writer, paranormal psychologist, and occult columnist—takes dark tourists through the unique and unusual history of each location.

There are must-see places you’ve probably heard of, like the remarkable Winchester Mystery House in San Jose, California, the Paris catacombs, and Skinwalker Ranch in Utah. But for the most part, Hollow takes us on a journey of truly obscure places I now need to go.

The Hanging Coffins of Sagada in the Philippines.

The Hanging Coffins of Sagada in the Philippines.In Luzon, Philippines, for example, there are the Hanging Coffins of Sagada. Rather than burying their dead, the Igorot people hang them in coffins on a mountainside to be closer to their ancestral spirits. “Although there are ongoing problems with the preservation of the coffins, including graverobbing, they are still accessible to those who wish to visit,” Hollow writes. As with each entry, a map is provided to help locate the site.

A witchcraft-themed chapter introduces readers to a “witchcraft” market in Bolivia, where shoppers can purchase goods from local “witch doctors” and spiritual healers, such as painted sugar to help ward off evil and love potions. And if you’ve been looking for a dead llama fetus, you’re in luck.

If you’re headed down under, be sure to check out Australia’s version of Area 51 at Wycliffe Well. As Hollow says, travelers “may find themselves surrounded by hundreds of little extraterrestrial beings.” The location has had reports of UFO sightings for more than fifty years. Like Roswell, New Mexico, the area has embraced its lore with widespread alien-themed décor.

Then there’s the Island of the Dolls in Mexico, where a haunted recluse has hung hundreds of creepy dolls from trees. Creepy might be an understatement.

These are just a few weird and wonderful examples you’ll find in Atlas of Paranormal Places, available September 3, 2024, from Ivy Press. So plan your itinerary, pack a bag—and pray you’ll return.

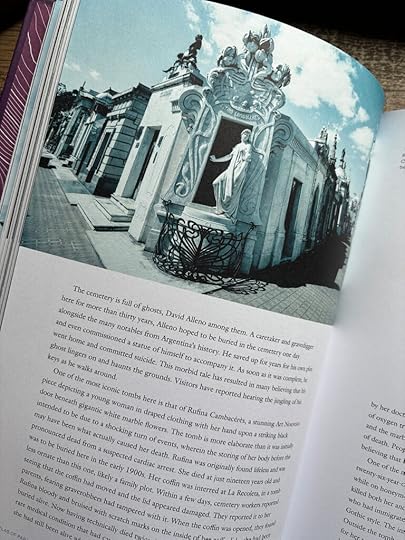

La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina. I visited several years and wrote about it for this site: “That Time When Body Snatchers Entered the City of the Dead.”

La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina. I visited several years and wrote about it for this site: “That Time When Body Snatchers Entered the City of the Dead.”.

<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post “Atlas of Paranormal Places” Enlightens Dark Tourists appeared first on Weird Historian.

August 13, 2024

The Man Who Didn’t Sleep for (At Least) Thirty Years

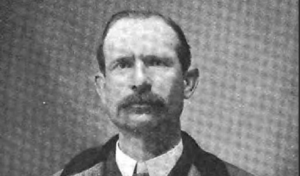

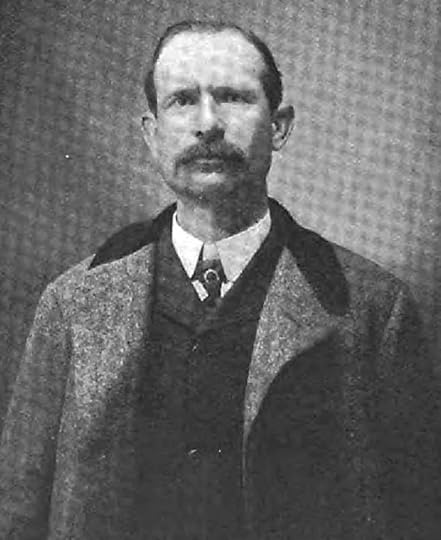

Albert Herpin appears to be wide awake, as always.

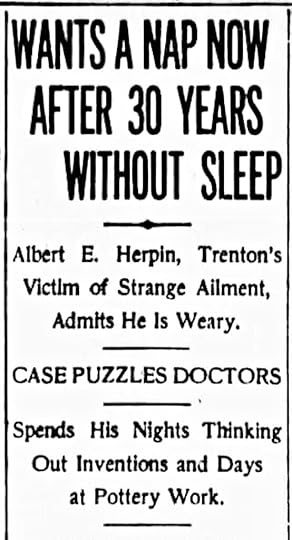

Albert Herpin appears to be wide awake, as always.Doctors generally recommend eight hours of sleep per night. Albert E. Herpin of Trenton, New Jersey, paid no attention to their health advice. Instead, he opted for zero hours a night for thirty years. But according to an April 1912 article in New York’s The Evening World, after three decades, he finally felt a bit weary.

“He says he is physically weak and believes a nap of only five minutes’ duration would give him new life,” the article stated.

Herpin wasn’t simply struggling to fall asleep; he had no desire to do so. He reportedly rested in an armchair for a few hours each night without closing his eyes, reading newspapers during these brief periods of respite. Otherwise, he stayed busy as a pottery maker and decorator, contributing innovations in underglaze and overglaze techniques. Remarkably, those who knew him claimed he never appeared drowsy despite his sleeplessness.

Albert E. Herpin, the Man Who Didn’t Sleep. As reported in The Evening World, April 10, 1912.

Albert E. Herpin, the Man Who Didn’t Sleep. As reported in The Evening World, April 10, 1912.There are varying accounts of when Herpin’s strange condition—or ability—began. The aforementioned article from 1912 claims it started in 1882 after the death of his wife. He was just thirty years old then. Years later, a 1936 report states his lack of sleep dates all the way back to his birth. “His mother was worried as all the other members of the family slept normally,” it said. In terms of general sleep, so did the rest of the human race. Doctors studied the sleepless wonder but were stymied and offered no help.

“I do not believe a man needs sleep, and I believe that I will live a long life without it,” Herpin told reporters. “Until a few days ago when I began to feel weary, I felt as well as I did when I was a young man. To tell you the truth, I would hate to sleep a part of my life away. I find that I can think and work better at night than I can in the day time. I have never been really sick in my life, and I believe that I am as strong today as any man of my age in this city.”

Herpin indeed lived a long life. He passed away on January 3, 1947, at the age of ninety-four and maintained his claim of sleeplessness for all those years.

<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post The Man Who Didn’t Sleep for (At Least) Thirty Years appeared first on Weird Historian.

August 7, 2024

Skull Moss: History’s Gruesome Cure for Whatever Ails You

Skull moss on display at the Witch House in Salem, Massachusetts. Photo by Marc Hartzman.

Skull moss on display at the Witch House in Salem, Massachusetts. Photo by Marc Hartzman.In previous centuries, the bodies of executed criminals were often allowed to be dissected and studied by anatomists. At other times, however, the bodies were left hanging in chains for long periods of time until the scalps wore away and the exposed skulls, like a stone, gathered moss.

During this time of misguided remedies and quackery, this “skull moss” was believed to have curative powers. The hanging of criminals supposedly forced the spirit of their vim and vigor into the head. As a result, the potent moss—also called usnea—was used to help stop bleeding (like gauze or, you know, maybe a tissue) and, according to a 1927 article, “was sought after as a sure antidote for neurasthenia and kindred ailments.”

IFLScience.com adds that “consumers would take those skulls and scrape them for their lichens” which were then ground up and “used to promote wound healing, treat whooping cough, and manage epilepsy, among other things.”

This fuzzy medicine appeared in encyclopedias as early as the late 1700s as a serious treatment and remained an official drug in pharmacopeias and was sold in apothecaries.

Newspaper ad from July 17, 1955.

Newspaper ad from July 17, 1955.In 1955, a newspaper ad for various pharmacies shared the strange skull moss history as an example of “odd treatments” and the “great strides” made in medicine—reminding readers to listen to their modern-day doctors and to bring prescriptions to their “pharmacy for prompt service.”

As bizarre as it sounds now, it surely seemed perfectly logical at the time. One can’t help but wonder what medical techniques and remedies of today will be mocked and laughed at in the next hundred years.

<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post Skull Moss: History’s Gruesome Cure for Whatever Ails You appeared first on Weird Historian.

August 5, 2024

Did Aliens Leave Their Elongated Skulls Behind?

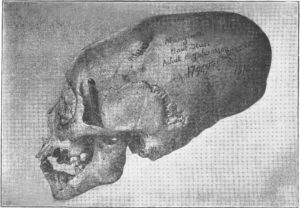

Deformed skull of Mombuttou or Mangbetu. René Verneau Collection. Bulletin of the National Museum of Natural History, no. 4, 1927.

Deformed skull of Mombuttou or Mangbetu. René Verneau Collection. Bulletin of the National Museum of Natural History, no. 4, 1927.If you’ve watched Ancient Aliens or read Erich von Däniken’s Chariot of the Gods, you may be convinced that earth has been visited by industrious extraterrestrials over the millennia. But if aliens were indeed responsible for ancient architecture, did any of them collapse from exhaustion and leave their skeletons for us to unearth?

Elongated skulls found frequently in Peru in other parts of the world have led some to believe they’re alien in origin. And not just Harrison Ford and Shia LeBouf in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Reports of DNA tests with findings not originating from this planet have circulated around the Internet and offered ancient alien theorists ammunition for their argument. So could they belong to the big-headed aliens typically called the “Grays”?

Curious as they may be, elongated or shaped skulls have long been understood to be entirely terrestrial. In fact, they date back 45,000 years to the Neanderthals. The process begins at infancy when the skull is still pliable. For example, on the island of Tomman in the South Pacific, a mother would put a bonnet woven from human hair and soaked in oil over her baby’s head. A basket woven from coconut fiber would be placed atop the bonnet, and the mother would pull the strands of the basket tighter, bit by bit each day, until the skull could be shaped no more. As a 1921 article explained, long before anyone considered elongated skulls to be extraterrestrial, “When the little Tommanite is about a year old, he emerges from his wrappings with a beautifully elongated, pointed skull, the pride of his mother.”

The Mangbetu tribe in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s remote northern region has also traditionally considered the misshapen skull a symbol of beauty and prestige. Some continue the practice to this day. Modern or ancient, their skulls’ DNA is entirely human.

This story was originally written for my book WE ARE NOT ALONE: The Extraordinary History of UFOs and Aliens Invading Our Hopes, Fears, and Fantasies (Quirk Books).

We Are Not Alone, by Marc Hartzman. Quirk Books, 2023.

We Are Not Alone, by Marc Hartzman. Quirk Books, 2023.The post Did Aliens Leave Their Elongated Skulls Behind? appeared first on Weird Historian.

June 20, 2024

When the Earth was Flat and Surrounded by Walls of Ice

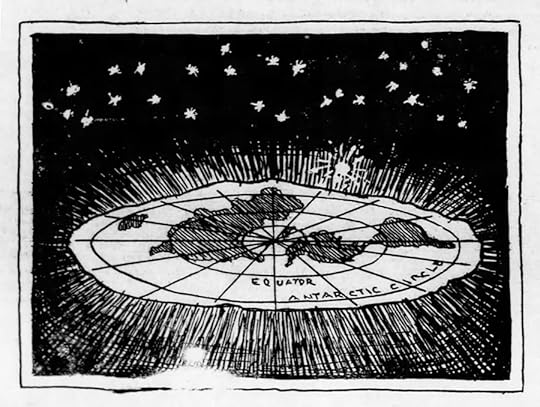

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 12, 1931.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 12, 1931.Decades into the twenty-first century there are still flat-earthers roaming the allegedly flat planet. As bizarre and anti-science as they are, they’re hardly new. In 1921, an Illinois school principal named Wilbur Glenn Voliva preached his flat earth theory to a thousand grade school and high school students.

Volivar contended that the flat earth has a north pole in the exact center (and no south pole) and is surrounded by a Game of Thrones-like wall of ice, which prevents sailors from falling off the rim. (Where would they land?) Students also learned that our flat world remains stationary in space and that the sun is a mere thirty-two miles in diameter and only three thousand miles away.

“The sun circles above the earth spirally, making one circuit of 360 degrees each twenty-four hours, always at the same height,” Voliva said. “The rising and setting of the sun are optical illusions; the sun is just as high at midnight as it is at midday, but is on the opposite side of the North Pole at midnight and because of its limited size and influence it cannot be seen.”

Wilbur Volivar’s map of the flat earth.

Wilbur Volivar’s map of the flat earth.Heaven is above earth and Hell is below. Voliva maintained that nothing in the Bible supports globular-earth theory. Though the Bible also lacks other scientific details about our world, which doesn’t negate their existence.

According to one of the school’s educators, the students grasp the flat earth concept easily because their “minds are not full of globular earth teachings such as older folks have had drilled into them.” So they fully accepted the theory. “I don’t believe there is one student in the grades who has questioned it. The flat earth seems more reasonable to them. The globular, unreal.”

Did they ever unlearn these lessons? Or did they raise today’s generation of believers?

<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post When the Earth was Flat and Surrounded by Walls of Ice appeared first on Weird Historian.