Marc Hartzman's Blog, page 3

June 16, 2024

Meet Thomas Inglefield: A Peek into the Pages of “Kirby’s Wonderful and Eccentric Museum”

Thomas Inglefield, an artist born without limbs, aged twenty. Engraving, 1804. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Thomas Inglefield, an artist born without limbs, aged twenty. Engraving, 1804. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.In centuries past, maternal impression was often given as a reason for children born with an anomaly. The most famous case is that of Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man. It was believed that his mother had been frightened by an elephant during her pregnancy. Her memory of the startling event allegedly left an “imprint” on the developing baby.

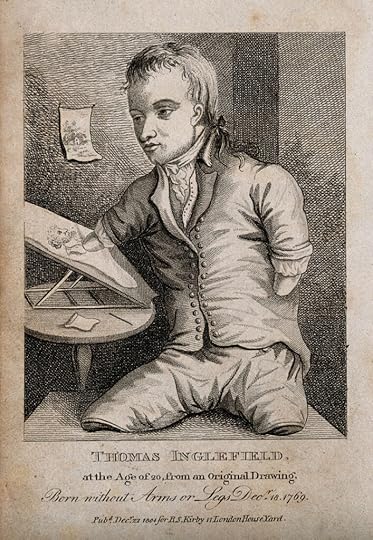

Another case was Thomas Inglefield, who was born without arms or legs in 1769. According to an account of his life in Kirby’s Wonderful and Eccentric Museum, Vol. 3 from 1820, his maternal impression was simply due to a “fright.” No further details are offered. Yet, despite lacking full limbs, Inglefield compensated with his stumps and the muscles of his mouth to hold a pencil and become an artist.

Amazing as Inglefield was, he’s lesser known today than his predecessor, Matthew Buchinger, the Little Man of Nuremberg (1674-1722). Buchinger was also born without arms or legs and became artist, magician, musician, marksman, and a father eleven times over. You can read more about him here, and more about Inglefield by staying on this page. The text that follows below is from Kirby’s:

IT is a proposition which, though trite, is not the less true, that nature compensates for the deficiencies observed in some of her works, by peculiar advantages. Thus among the animals with which she has peopled the surface of the globe, we universally find that what one wants in strength or courage, it possesses in artifice and cunning. In the same manner, the mole, whose defect of the organs of sight is so notorious, is endowed with powers of hearing so acute and so delicate, as to be enabled by means of them, to shun the most imminent dangers with which it may be threatened. That this principle likewise extends to the human species, the subject of the present article furnishes a remarkable instance.

Thomas Inglefield was born December 18, 1769, at Hook, in Hampshire. He came into the world without either arms or legs; and this extraordinary conformation is supposed to have been the consequence of a fright which his mother experienced during her pregnancy.

Though nature, by denying him those members appeared to have rendered him unfit for almost all the purposes of life, yet she had bestowed on him such industry and ingenuity, that, notwithstanding the great disadvantages under which he laboured, he acquired the arts of writing and drawing. For a person in his situation, these exertions appear almost incredible: but it is not the less true, that Mr. Inglefield himself etched portraits and other drawings very neatly. The manner in which, by long practice, he attained the facility of performing these operations, was by holding his pencil between the stump of his left arm and his cheek, and guiding it with the muscles of his mouth.

Mr. Inglefield resided some years since at No. 8, in Chapel-street, Tottenham-court-road, London, and was visited by most of the nobility and gentry, to witness his performances, by which he obtained many presents; but whether he is still living or not, we have not been able to ascertain.

Thomas Inglefield, an artist born without limbs. Etching by T. Inglefield, 1787, after C.R. Ryley. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Thomas Inglefield, an artist born without limbs. Etching by T. Inglefield, 1787, after C.R. Ryley. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection.<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post Meet Thomas Inglefield: A Peek into the Pages of “Kirby’s Wonderful and Eccentric Museum” appeared first on Weird Historian.

June 13, 2024

The Case For Spirit Photography is Back From the Dead

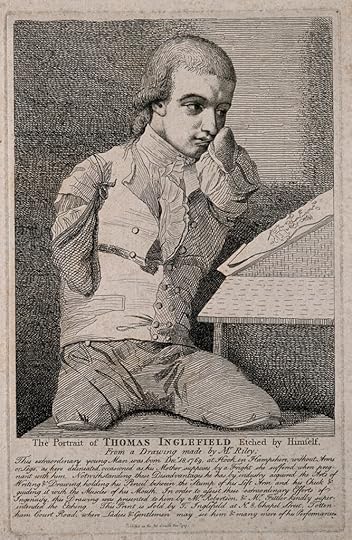

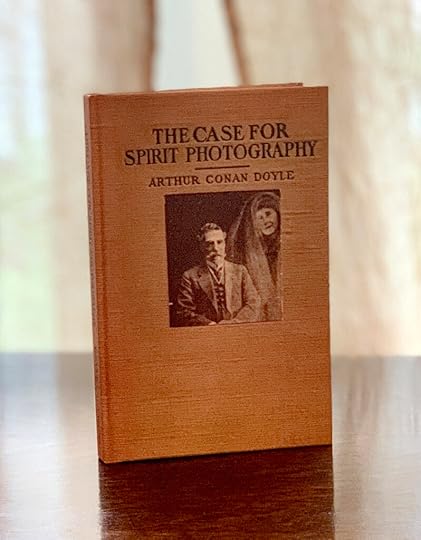

“Can the camera show us those who have passed on? Yes!” Arthur Conan Doyle said upon publishing The Case For Spirit Photography in 1923. The book offers a thorough account of his own experiences with spirit photography and those of others. An original copy is rare and expensive, but fortunately it’s now available in a beautiful, faithfully reproduced edition from Curious Publications.

The Case For Spirit Photography, by Arthur Conan Doyle. Originally published in 1923. Reproduction now available from Curious Publications.

The Case For Spirit Photography, by Arthur Conan Doyle. Originally published in 1923. Reproduction now available from Curious Publications.The first spirit photographer, William Mumler, began working in Boston in 1861. Faint figures believed to be lost loved ones appeared in photos behind those sitting in front of the camera. Over the years, Mumler took thousands of spirit photographs, including one of Mary Todd Lincoln showing the assassinated president behind her. P.T. Barnum, always one to enjoy a good humbug, was intrigued as well and displayed several Mumler photographs in his American Museum.

But with growing success came more skeptics. And eventually, some of them noticed that several spirits were actually people still living. By 1869, the police were on the case and claimed Mumler was swindling people out of their money. The spirit photographer went to court, supported by the Spiritualist community who maintained their belief that he was innocent and genuine. Mumler was exonerated when no one could prove he’d faked his photos. His legal troubles ultimately hurt his business, but spirit photography lived on through other mediums wielding otherworldly cameras.

Doyle believed many of them to be genuine and often came to the defense of photographers accused of fraud. He had been one of Spiritualism’s loudest and best-known evangelists in the early twentieth century. He, and its millions of followers, believed that we never die—we merely move on to another plane that could amazingly be captured on film.

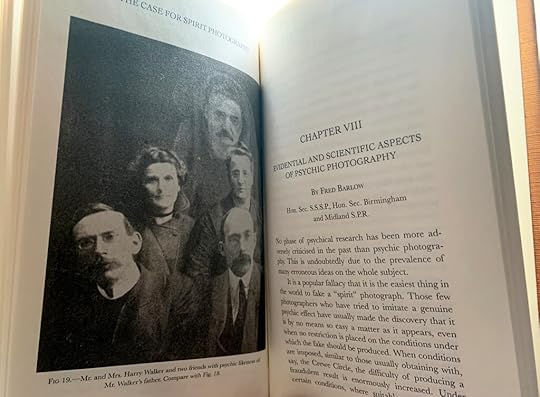

Examples of spirit photography from The Case For Spirit Photography.

Examples of spirit photography from The Case For Spirit Photography.The author’s good friend, Harry Houdini, spent many years exposing fraudulent mediums that capitalized on Spiritualism and people’s willingness to believe that the dead could talk. One example was spirit photographer Alexander Martin of Denver, Colorado. Doyle told Houdini that he was “a very wonderful man in his particular line.” So the magician paid him a visit, and once inside the studio he attempted to explore the dark room.

After a few secretive photographic shenanigans, Martin shared some ghosts. Houdini concluded the photos were simply double exposures. “From a logical, rational point of view, Spirit photography is a most barefaced imposition and stands as evidence of the credulity of those who are in sympathy with the superstitions of occultism,” he wrote in 1924’s A Magician Among the Spirits. “It is also evidence of how unscrupulous mediums become and how calloused their consciences.”

Doyle clearly disagreed. Genuine or not, the stories presented within these pages are fascinating and a hundred years later the photos remain extraordinary.

More examples of spirit photography from The Case For Spirit Photography.

More examples of spirit photography from The Case For Spirit Photography.<br />(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});<br />

The post The Case For Spirit Photography is Back From the Dead appeared first on Weird Historian.

May 27, 2024

Martians, Hoaxers, and UFOs at the Turn of the Century: The Great Airship Flap of 1896 and 1897

Illustration of an early airship sighting in Sacramento, from the San Francisco Call, November 19, 1896.

Illustration of an early airship sighting in Sacramento, from the San Francisco Call, November 19, 1896.When Kenneth Arnold saw flying saucers in 1947 and launched a frenzy of UFO reports across the country, it wasn’t the first time such a phenomenon had occurred. A similar surge of sightings took place fifty years earlier.

As the turn of the century neared, marvelous new inventions like the telegraph, telephone, and x-ray amazed and excited the world. “This is an age of wonders,” wrote one newspaper reporter. “The marvels of human invention are multiplying, and we know not where to draw the line at the impossible.” So it’s not shocking that flying machines seemed a perfectly reasonable development. Or that people allegedly started seeing them by the end of 1896, when a wave of “airships” traversing the skies captured the country’s curiosity and imagination. They started in California and worked their way east, with newspapers along the way enthusiastically covering accounts of witnesses and frequently citing their “undoubted veracity.” This was about three years before the first Zeppelin appeared and the Wright brothers’ first flight wasn’t until 1903. Aside from hot air balloons, things just weren’t traversing the skies yet.

These airships, like the ones seen in November 1896 in Sacramento and the Bay Area, were typically described as “egg-shaped” or as having a “bird-like body” floating in the air with a “brilliant searchlight” and “fan-like wheels on either side” propelling them at about twenty miles per hour. Some witnesses claimed to have seen up to four passengers on one and heard them reveling in “merry song and laughter.” Others heard them speaking English as they expressed concern about their low elevation.

Naturally, there were those who tried to take credit. Several attorneys assured the press that they represented the inventors who were simply waiting for patents before staking their claim to fame with an official announcement about the airship. One of these lawyers, General William Henry Harrison Hart, used the airship to deliver his own political message, telling the San Francisco Examiner that he had advised his client to use the airship for war. “I believe that by means of this airship a great city could be destroyed in forty-eight hours.” The specific conflict Hart had in mind was the ongoing Cuban War of Independence, and the Spanish-governed Havana was the city to be destroyed.

Where there were airships, naturally there would be people who said they flew in one. John A. Horen, the chief electrician of the San Jose Electric Improvement Company, was just such a person. Horen announced that he had installed his own patented “sparkling apparatus” in an inventor’s vessel, after which the two flew more than two thousand miles from San Francisco to Honolulu. This particular airship featured aluminum construction and stretched 163 feet in length and stood twenty-three feet high. It featured propellers at both ends, a “telescopic apron” in front, and curtained windows, from which he gazed through over Hawaii. The airship sounded fantastic, because, as his wife later told the Examiner, it was. Horen, she said, was a “star practical joker and was having some sport at someone’s expense.” During the supposed flight the chief electrician was, Mrs. Horen noted, “doing some of the soundest sleeping of his life.”

Sketch of the airship John A. Horen allegedly flew in from San Francisco to Honolulu, as seen in the San Francisco Examiner, December 2, 1896.

Sketch of the airship John A. Horen allegedly flew in from San Francisco to Honolulu, as seen in the San Francisco Examiner, December 2, 1896.As the months went on the airships made their way across the south, the Midwest, and the northeast. Many sightings continued to find explanations through potential human ingenuity. Martian pilots were occasionally accused, though usually in jest, like when a Tennessee reporter remarked, “maybe some enterprising Martian has determined to surprise our earth, and has selected Tennessee’s Centennial occasion to make his appearance in spite of all the difficulties of ethereal passage.”

By mid-April, Martian airships had swarmed Texas. During a five-day span there were sightings reported in twenty-one towns. The most unusual incident took place in Aurora when the Dallas Morning News claimed a craft with apparent mechanical difficulties “collided with the tower of Judge Proctor’s windmill and water tank destroying the judge’s flower garden.” If the flying machine and floral fiasco weren’t shocking enough, the paper went on to say the sole pilot’s remains were “badly disfigured” but “enough of the original has been picked up to show that he was not an inhabitant of this world.” A local astronomer, T. J. Weems, declared the visitor was a “native of the planet Mars.” Scattered papers were supposedly found with mysterious hieroglyphics and remnants of the ship were “built of an unknown metal.” Though the body of such a being might be expected to be thoroughly examined, the article stated a funeral would be held the next day.

Were these “airships” actually early versions of flying machines? Or as some ufologists believe, were they from another world? In 1973, the United Press International ran a story about the International UFO Bureau’s attempt to exhume the buried Martian in Aurora. According to the group’s director, Hayden Hewes, this would allow them to “obtain some of the same type of unusual metal from either his clothing or bones that was unearthed at the well site when we checked it with metal detectors.” They’d spent three months checking the grave with metal detectors and gathering information. “We are as certain as we can be at this point he was the pilot of a UFO which reportedly exploded atop a well on Judge J. S. Proctor’s place, April 19, 1897.”

Members of MUFON (then the Midwest UFO Network) joined in on the investigation as well. The group, along with a local reporter, believed they found a fused nugget of aluminum alloy that didn’t exist on earth at the time. They also found a few residents who still remembered the event, like ninety-one-year-old Mary Evans who said the crash “certainly caused a lot of excitement,” though her parents wouldn’t let her join them at the site. At ninety-eight years old, G. C. Curley recalled two friends picking up pieces of metal from the crash and telling stories of a dismembered body.

Unfortunately for Hewes and other UFO believers, the Aurora Cemetery Association blocked the exhumation and prevented a possible end to the case, one way or another. So the story lived on and drew more curiosity seekers to the town in search of the spaceman’s grave. By 1979, Time magazine covered the bizarre incident and quoted eighty-six-year-old local historian Etta Pegues as saying the Dallas Morning News article was written “as a joke and to bring interest to Aurora.”

No Martian plummeted into a windmill—according to Pegues, Proctor didn’t even have a windmill—nor are there any town records of an airship (terrestrial or extraterrestrial) crashing in Aurora. As for Weems the astronomer, it turned out he was actually the local blacksmith. The once-prosperous town had fallen on hard times since a newly built railroad caused trains to completely bypass the area. So why not capitalize on the craze? If an airship crashed and a Martian pilot had been buried there, Aurora could become a tourist attraction and revitalize the economy. In that sense, the small Texas town was a precursor to Roswell.

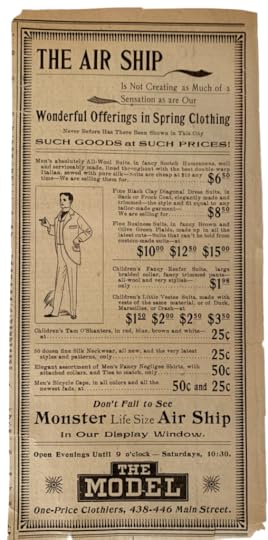

The popularity of the airships led to some advertisers using “Monster Life Size” models of the flying machines to drum up business.

The popularity of the airships led to some advertisers using “Monster Life Size” models of the flying machines to drum up business.While natural phenomena, hoaxes, and publicity stunts may have explained many of the sightings, it’s possible that some of the airships were actually just that, airships. Even though the first Zeppelin didn’t appear for about three more years and the Wright brothers’ first flight wasn’t until 1903, other inventors had been tinkering with the idea of conquering the air. In May 1896, Samuel P. Langley, who served as the secretary of the Smithsonian institute, boasted the successful unpiloted flight of his own flying machine over the Potomac River. The “aerodrome,” as he called it, derived its power from a steam engine and propellers. The fourteen-foot-long vessel traveled about a half mile at about twenty miles per hour. Fellow inventor Alexander Graham Bell lauded the test flight, claiming it moved “in one continuous gentle ascent as it swung around the circles like a great soaring bird” before its steam ran out and it “slowly and gracefully” came to a landing.

Whether Langley’s invention had been quietly improved upon over the next few months or not, the greatest phenomena may have been that of the media’s influence. They couldn’t get enough of the airship stories. It had mystery, drama, and in an age of invention, why not the real possibility of a flying machine? Some papers, however, made attempts to put the stories to rest. Just days after reporting Horen’s Honolulu story, the San Francisco Examiner called out its rival, the San Francisco Call, for leading the charge and perpetuating the sensation:

“Fake journalism” has a good deal to answer for, but we do not recall a more discreditable exploit in that line than the Call’s persistent attempt to make the public believe that the air in this vicinity is populated with airships. It has been manifest for weeks that the whole airship story is a pure myth. … It has had new airship fakes every day, each introduced with “scare heads,” assuring the trustworthiness of the story.

The countless reports and endless fascination of The Great Airship Flap of 1897, as it became known, serves as a microcosm of what was to come half a century later when people looked up to the sky and saw airships once again. Just more saucer-shaped this time.

This story was originally written for my book WE ARE NOT ALONE: The Extraordinary History of UFOs and Aliens Invading Our Hopes, Fears, and Fantasies (Quirk Books), and later ran in the January 2024 issue of the MUFON Journal.

We Are Not Alone, by Marc Hartzman. Quirk Books, 2023.

We Are Not Alone, by Marc Hartzman. Quirk Books, 2023.The post Martians, Hoaxers, and UFOs at the Turn of the Century: The Great Airship Flap of 1896 and 1897 appeared first on Weird Historian.