Gabriel Mckee's Blog: SF Gospel

May 27, 2015

The Way the Future Never Was: A Visual Appendix

To get a better idea of Brad Torgersen's problem with today's science fiction, let's take a look at some good, old-fashioned, reliably-packaged SF.

Hey, that looks like a space marine! This must be an old-fashioned classic of military SF, right? And, oh, hey, it won a Hugo in one of Brad���s favorite decades, the 1970s! Nope, turns out it���s really just some anti-Vietnam War propaganda. No fair drawing us in with gung-ho genre trappings and then giving us the horrors of war!

Hey, this one looks fun. It���s got space ships and all kinds of stuff. Wait, what? It���s about the evils of capitalism? Bait and switch!

Good ol��� Moses of the NRA in a rollicking adventure where he fights gorillas? Nope, turns out it���s really about racial prejudice. Oh, and the horrors of war. Man, that's a popular one!

Hey, look-- this one won a Hugo AND a Nebula in the ���70s. It���s got some outer space-y stuff going on. Some kind of weird ice planet thing happening. What���s that? It���s also entirely about gender issues? Huh. Wait a minute��� does Brad Torgersen think this book came out in the 2000s? That would explain a lot.

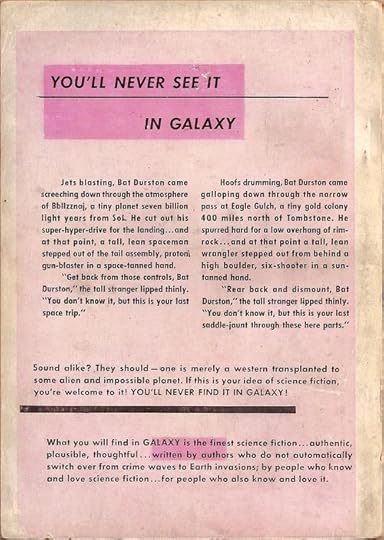

OK, Galaxy is gonna set everybody straight. Here���s a house ad from their first issue, where they explain that all SF fans want is straightforward adventure. Ummm��� Oh, wait. Actually, it kinda sounsd like they're making fun of straightforward adventure stories. Says they���re basically just space westerns, and implies that that���s boring. Yikes.

Well, this one���s got space ships and stuff. But I read it and it turns out it���s just some weepy beta-male character study or something. Nobody gets blasted with a ray gun at all.

This seems like some kind of fun, lighthearted portal fantasy. But apparently it���s actually just a big Christian allegory. (Does that count as Puppy-saddening?)

Oh, I know that guy���that���s Captain Kirk! This must be one of those straightforward, rock-���em, sock-���em, social-justice-messages-need-not-apply space adventures that attracted us to SF in the first place. Yeah, and Brad even quoted its opening monolog when he was talking about what great SF is supposed to be! This must be the thing. Wait, what? This one���s about racial prejudice and the horrors of war?

Well, shucks. I give up. Maybe Brad Torgersen really is just pining for a future that never was.

The Way the Future Never Was

So you���ve probably heard about this Sad Puppies/Rabid Puppies thing.

I���m reading Brad Torgersen���s Sad Puppies 3 manifesto (which I use not as a pejorative, but as an honest-to-goodness genre term) from a few weeks ago, and��� I���m just really confused. Maybe somebody can help me out here.

After an extended metaphor about breakfast cereals, Torgersen states what he considers the problem:

A few decades ago, if you saw a lovely spaceship on a book cover, with a gorgeous planet in the background, you could be pretty sure you were going to get a rousing space adventure featuring starships and distant, amazing worlds. If you saw a barbarian swinging an axe? You were going to get a rousing fantasy epic with broad-chested heroes who slay monsters, and run off with beautiful women. Battle-armored interstellar jump troops shooting up alien invaders? Yup. A gritty military SF war story, where the humans defeat the odds and save the Earth. And so on, and so forth.

These days, you can���t be sure.

The book has a spaceship on the cover, but is it really going to be a story about space exploration and pioneering derring-do? Or is the story merely about racial prejudice and exploitation, with interplanetary or interstellar trappings?

There���s a sword-swinger on the cover, but is it really about knights battling dragons? Or are the dragons suddenly the good guys, and the sword-swingers are the oppressive colonizers of Dragon Land?

A planet, framed by a galactic backdrop. Could it be an actual bona fide space opera? Heroes and princesses and laser blasters? No, wait. It���s about sexism and the oppression of women.

Finally, a book with a painting of a person wearing a mechanized suit of armor! Holding a rifle! War story ahoy! Nope, wait. It���s actually about gay and transgender issues.

Or it could be about the evils of capitalism and the despotism of the wealthy.

So��� huh. OK, it sounds like Torgersen doesn���t like metaphor in his SF. If it���s got a spaceship on the cover, and it���s got themes that don���t have to do with spaceships, it���s apparently a problem. In a long-but-well-worth-your-time blog post on the 2015 Hugos debacle, Philip Sandifer describes this as ���the spectacle of a grown man complaining about how he just can���t judge a book by its cover anymore.���

But this is where I get really confused, folks: what the hell era of SF is he talking about? Later in the post he indicates that he���s talking about the 1960s through the 1980s... which I���d say is a period pretty well defined by the metaphorical treatment of social and political ideas in SF. If you want to go back to a time when rocket ships and ray guns really meant just rocket ships and ray guns, you���d have to go back to the 1940s. And there are surely people who like Golden Age SF quite a bit, but for my tastes, I think it wasn���t really until the dawn of the digest era in the 1950s that SF got really, really good.

So I���m really confused. I can���t even recognize the picture that Torgersen paints as a caricature of SF publishing history. And since he coyly generalizes, you can���t even identify what books or authors he has particular problems with. (One name that���s emerged as one of his major b��tes noirs is John Scalzi���whose Old Man's War series has its sociopolitical scales tipped so far in favor of gee-whiz adventure that it should float Torgersen���s boat right out of the bathtub.) (It's pretty militaristic, too, if that's a factor.)

He says he���s OK with SF about social and political issues, as long as we don���t ���put these things so much on permanent display, [so] that the stuff which originally made the field attractive in the first place ��� To Boldly Go Where No One Has Gone Before! ��� is pushed to the side���. But to thousands of readers, ���boldly going��� means exploring just those issues that Torgersen has a problem with. And exploring those issues in SFnal terms is a time-honored tradition, going back a decade or so before the time that he considers the good old days.

For a lot of us, SF���s ability to deal with current problems in metaphorical terms is the whole point. It���s why we got interested in the genre, and why we���ve stuck with it���because there will always be new quesitons, and new angles on them. Does Brad Torgersen really want SF to be a genre about space ships and ray guns with no resonance with current society? Does he really want SF authors to abandon the time-honored tradition of exploring social issues with SFnal metaphor? That sounds to me like an SF that���s afraid of the future.

May 20, 2015

The problem with Game of Thrones...

It���s been a bit of a long silence on this blog, though I���ve written quite a bit in the apparent interim (including an article on Doctor Who as a rebel messiah and an entire book on Edgar Allan Poe). I���m coming out of the hiatus to talk about a subject that doesn���t have a lot to do with theology, though it has a lot to do with the ethical responsibilities of storytellers���so I guess it���s at least a little bit in scope. I���m talking about the increasing centrality of sexual violence on HBO���s Game of Thrones.

At this point, there have been many responses to last week���s episode of Game of Thrones, on which another major female character is subjected to rape. Many of these responses have argued that these sexual assaults serve no purpose in the story. But the problem with Game of Thrones��� pattern of shoehorning in major-character sexual assaults isn���t that these incidents serve no purpose. It���s the opposite���that they do serve a central purpose: to rob the story���s women of their agency, in direct contradiction to the thematic core of the novels on which the series is purportedly based.

I stopped watching Game of Thrones last year. I was irritated by Jaime Lannister���s rape of Cersei, but not quite enough to put me off the show entirely. For me, the bigger problem was the fact that the show was beginning to feel lackluster and repetitive. Rather than the plot and character beats that drove the first season or the novels, the show seemed to be more concerned with when they would next be able to show someone being disemboweled, or getting naked, or both. The show stopped holding my attention, so I pretty much half-watched season 4. When the camera lingered on Tyrion���s face as he strangled Shae at the season���s end (an event which is, admittedly, present in the novel), I realized I was not likely to get any enjoyment out of the show again. I was, as they say, done.

Which means I haven���t seen ���Unbowed, Unbent, Unbroken,��� so I���ll limit my comments on it here, and instead focus mainly on stuff from the past that is confirmed and worsened by the latest turn of the stomach events. In short, I always kind of thought that maybe I���d go back and watch GoT again, in case maybe the stuff that had turned me off last year got better. Well, now I know that it sure doesn���t get any better.

For me, the core storyline of A Song of Ice and Fire concerns the powerless of Westeros. The key characters (Tyrion Lannister, Jon Snow, Daenerys Targaryen, Cersei Lannister) and important lesser ones (Samwell Tarly, Catelyn Stark, Yara Greyjoy, etc.) are denied power by their society, which is, yes, violent and cruel. Tyrion and Samwell are denied authority because of their physical limitations; Jon Snow by his birth status; Daenerys and Cersei by their gender; Jaime by the criminal act that earned him the title Kingslayer; Brienne by her physical appearance and gender. But in every case, the story shows us the ways in which these characters claim the agency that is explicitly denied to them. The story is about how they seek, and find, control over their destinies, despite being apparently powerless to change their circumstances. They refuse to let themselves be victims.

The television adaptation of this source material, on the other hand, inverts this���at least for the female characters. The women who we see fighting to find their voices in the novels are instead shown being punished with rape. Benioff and Weiss have taken the female characters whose quest for self-determination is, for many readers, the heart of the novels, and used sexual violence to put them back in their place.

This is not a new problem on the show. The recent scene with Sansa is, if anything, merely confirmation of a pattern. The problem was clarified last year with Jaime���s rape of Cersei. But it goes back much further than that, to the treatment of Daenerys in the first season. Not having read ASOIAF when I watched the first season, I didn���t realize how drastically her wedding night was changed from the source material, and what that change meant for her character. The book shows us one of the clearest cases of explicit consent you���re likely to find in the history of literary sex scenes. Daenerys is clearly in charge, and Drogo waits for an explicit ���yes��� from his bride before proceeding. In the show, he rapes her. This drastically changes the meaning of Daenerys��� story. In the novels, her power comes from the fact that she brings this nobility out of her husband, teaching compassion to a nation that had previously been based in cruelty. In the show, her power comes from the fact that she falls in love with her rapist.

And that, in a nutshell, is what���s wrong with the treatment of rape on Game of Thrones the show. The problem isn���t that sexual violence���which is absolutely a part of the source material���is present in the show. (One could certainly argue about the differing amount of narrative time and energy spent on sexual violence between source and adaptation, of course.) The problem is that, in an attempt to ���streamline��� the narrative, or make certain story arcs more ���cinematic,��� Benioff and Weiss have fairly systematically victimized precisely those characters who embody the novels��� core themes of marginality and self-determination. Three key women���Daenerys, Cersei, and now Sansa���have essentially been put in their place by men with greater social power. And Drogo and Jaime���who in the books appear, on the whole, pretty noble���are now tarnished as abusers.

Benioff and Weiss���s approach to their adaptation does violence, not simply to the characters in question, but to the very meaning of the source material. It takes a story that shows us that power, agency, and dignity are not the sole right of those with the strongest sword arms, and turns it into a story that equates power with penetration. They have fundamentally missed the point. The result is an act of vandalism.

I���ll close with a few links, since other folks who have been watching this season have said things both eloquent and passionate on the current state of the problem that are worth reading.

For the LA Review of Books, Sarah Mesle brilliantly takes down the tired argument that this fictional, fantasystory represents, or even could represent, ���the way it really was.���

In a roundtable review of the latest episode for the Atlantic, Christopher Orr succinctly sums up the ever-present, ever-worsening problem of titillation on the show: "...showrunners Benioff and Weiss still apparently believe that their tendency to ramp up the sex, violence, and���especially���sexual violence of George R.R. Martin���s source material is a strength rather than the defining weakness of their adaptation."

The Mary Sue will no longer be covering the show in any way, and explains their reasons here.

On a more visceral level, I���ve been getting a lot of satisfaction out of the Twitter feed of @AngryGoTFan, who also has a blog for lengthier rants.

April 12, 2013

Recent & forthcoming work

A couple projects have been percolating behind the scenes here: First, I've contributed material to the forthcoming book Enjoy The Experience: Homemade Records 1958-1992. The book is a detailed look at privately-press/self-released records from the '50s-'80s and the sometimes quite idiosyncratic minds that created them: from hotel lounge bands to slightly cracked basement folk crooners and everything inbetween. My contributions to the book are biographies of several religiously-slanted recording artists who pressed their own records in the '60s: Christian rock pioneer Ron Russo; Jimmie Davis, the founder of a fundamentalist summer camp; Darwin Gross, the disgraced former head of Eckankar; and gospel trumpeter Ray Torske. (A bio of Thurlow Spurr, founder of traveling high school/evangelical/car safety band the Spurrlows, was cut for length, but will hopefully find its way into online publication in the near future). The book is available now for pre-order at store.sinecurebooks.com.

A couple projects have been percolating behind the scenes here: First, I've contributed material to the forthcoming book Enjoy The Experience: Homemade Records 1958-1992. The book is a detailed look at privately-press/self-released records from the '50s-'80s and the sometimes quite idiosyncratic minds that created them: from hotel lounge bands to slightly cracked basement folk crooners and everything inbetween. My contributions to the book are biographies of several religiously-slanted recording artists who pressed their own records in the '60s: Christian rock pioneer Ron Russo; Jimmie Davis, the founder of a fundamentalist summer camp; Darwin Gross, the disgraced former head of Eckankar; and gospel trumpeter Ray Torske. (A bio of Thurlow Spurr, founder of traveling high school/evangelical/car safety band the Spurrlows, was cut for length, but will hopefully find its way into online publication in the near future). The book is available now for pre-order at store.sinecurebooks.com.

I've also contributed to a forthcoming book on Doctor Who. I can't say much more than that now, but look forward to more information soon!

December 5, 2012

Radio Free Albemuth at the Philip K. Dick Film Festival

This weekend is the Philip K. Dick Film Festival in Brooklyn (not to be confused with this past fall's Philip K. Dick Festival in San Francisco), and kicking off the event is a rare screenings of John Alan Simon's (alas) still-undistributed film adaptation of Radio Free Albemuth. If you haven't seen it-- and chances are you haven't, as it's only been shown a handful of times-- it's well worth checking out. The screening is at 7:30 on December 7th (2012) at Indiescreen in Williamsburg. (Boardwalk Empire fans note that the role of Phil is played by Shea Whigham, AKA Eli Thompson!)

Read my review (written after the film's last New York screening two years ago) if you need any convincing.

[Edit: Note that there is only one screening, not two-- the website information is a bit misleading.]

SF Signal's Mind Meld: Star Wars VII-IX

December 2, 2012

SF novels in the Christian Century's holiday gift guide

The current issue of the Christian Century features a list of some of the year's best SF novels, reviewed by myself and the inimitable James McGrath. Our reviews of Doctor Who: Shada by Gareth Roberts, Existence by David Brin, Redshirts by John Scalzi, the Library of America's 2-volume anthology of 1950s American Science Fiction, At the Mouth of the River of Bees by Kij Johnson, and Triggers by Robert J. Sawyer are on the Christian Century's website, and appear in print in the December 12th, 2012 issue.

The current issue of the Christian Century features a list of some of the year's best SF novels, reviewed by myself and the inimitable James McGrath. Our reviews of Doctor Who: Shada by Gareth Roberts, Existence by David Brin, Redshirts by John Scalzi, the Library of America's 2-volume anthology of 1950s American Science Fiction, At the Mouth of the River of Bees by Kij Johnson, and Triggers by Robert J. Sawyer are on the Christian Century's website, and appear in print in the December 12th, 2012 issue.

Alas, there was not room for every book worth mentioning in the list. Below are three reviews that didn't make the final cut for the final piece, but would definitely still make great gifts:

Merge/Disciple by Walter Mosley

Merge/Disciple by Walter Mosley

Tor Books, 288 pp., $24.99 hardcover,

$7.99 Kindle edition

Presented in the style of an “Ace

Double”—a format from the 1950s in which two short novels were bound

back-to-back, each with a separate cover—these two novellas use SF tropes to

explore the nature and ethics of power. In Merge,

a man becomes enmeshed in a struggle for the future of the planet when he shows

compassion to a strange and possibly dangerous alien being; in Disciple an unambitious office drone

begins receiving mysterious messages from an otherworldly power that seems able

to grant his every wish.

Boneyards by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Boneyards by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Pyr/Prometheus, 301 pp., $16 trade

paperback, $8.69 Kindle edition

The third book in Rusch’s “Diving Into

the Wreck” series chronicles the further adventures of Boss, an enterprising

far-future archeologist. Boss specializes in leading tourist excursions to the

hulking wrecks of ancient spaceships, particularly ships known as “Dignity Vessels”

that operate using the mysterious, otherworldly technology of the anacapa drive. This volume expands the

backstory of Rosealma (nicknamed “Squishy”), a character tortured by her role

in anacapa research that led to the

death or disappearance of hundreds of researchers. It’s a fine entry in this

series of moody, atmospheric space opera.

Only Superhuman by Christopher L. Bennett

Only Superhuman by Christopher L. Bennett

Tor Books, 352 pp., $24.99 hardcover, $11.99 Kindle edition

Bennett’s richly-imagined novel is a hard-science fiction

superhero story. Set in a future where the solar system is populated by

genetically-modified “Troubleshooters,” the story follows Emerald Blair, a

young criminal-turned-hero who travels the asteroid belt righting wrongs and

battling gene-modified maniacs. Blair’s story is interesting, but the texture

and detail of the universe she inhabits that stands out is the novel’s most

notable feature.

June 12, 2012

Prometheus: Looking For God in All the Wrong Places

Prometheus opens with the discovery of an intelligent designer: two scientists have found evidence of ancient contact between human beings and aliens, and they become part of a mission to reach what they believe to be these aliens’ home planet to meet our makers. When the mission, funded by the unimaginably wealthy, Methuselan industrialist Peter Weyland, finally reaches the Earthlike moon LV-223,* they explore a massive artifact created by these “Engineers." This massive dome is filled with evidence of their genetic experiments, much of it housed in a room dominated by a giant statue of one of the beings' heads: a temple, perhaps, to their own creative genius. The dome is dead—one character even describes it as a tomb—but the presence of these travelers awakens a startling variety of life inside, including one of the Engineers themselves. And the explorers—particularly archeologist Elizabeth Shaw—discover that intelligent designers need not be benevolent ones.

Prometheus opens with the discovery of an intelligent designer: two scientists have found evidence of ancient contact between human beings and aliens, and they become part of a mission to reach what they believe to be these aliens’ home planet to meet our makers. When the mission, funded by the unimaginably wealthy, Methuselan industrialist Peter Weyland, finally reaches the Earthlike moon LV-223,* they explore a massive artifact created by these “Engineers." This massive dome is filled with evidence of their genetic experiments, much of it housed in a room dominated by a giant statue of one of the beings' heads: a temple, perhaps, to their own creative genius. The dome is dead—one character even describes it as a tomb—but the presence of these travelers awakens a startling variety of life inside, including one of the Engineers themselves. And the explorers—particularly archeologist Elizabeth Shaw—discover that intelligent designers need not be benevolent ones.

The Engineers, much like Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker, are experimenting artists, playing with DNA to create a plethora of new and terrifying forms. And, like a more plainly amoral version of the Star Maker, this experimentalism is sinister, not only because the beings they are creating are violent, but because they display no regard for the feelings of their (accidentally?) sentient creations. The dome, we learn, houses a spaceship whose aborted, millennia-old mission was to return to Earth to wipe out all life there.** There’s a hint that human beings are not a deliberate creation of the Engineers, but an accidental one: the enigmatic opening scene shows one of the alien beings dissolving himself at the molecular level on an unknown world, the strands of his DNA splitting apart as he collapses into some ancient river. Perhaps this dissolution was incomplete, and we are the result of some surviving genetic detritus. If this is the case, perhaps the reason that the Engineers wish to destroy us is that we can’t be used as weapons, as their more deliberate creations can: we lack sufficient use-value.

Clearly, Prometheus is a story about the quest for origins, but it is also about faith and the loss thereof. Shaw—who none-too-subtly wears her father’s crucifix around her neck for much of the film, and is seen in flashbacks discussing the afterlife with him—is brought on the mission because Weyland considers her a “true believer.” She has faith that the Engineers exist, that they created us, that they will be willing to answer our questions, and that some ineffable benefit can result from contact with him. On the former two points she turns out to be correct, but she is categorically wrong on the other two. In order for her to save the world—stopping the surviving Engineer from returning to Earth to destroy humankind—she must quickly and decisively lose her faith. It’s not clear what we’re supposed to make of this, thematically: is the entire project of seeking after answers to our questions of purpose what’s to blame for this mission’s tragic end? Are the Engineers, these not-gods, simply the instruments of some offscreen gods in the punishment of that most ancient of sins—hubris?

Prometheus doesn’t entirely know what myth it wants to be in. The title suggests it’s the story of the Titan who stole fire from the gods and bequeathed it to humankind: the originator of all technology and, by extension, the creator of human sentience. This seems to be the myth that Peter Weyland thinks he’s in, as he gave the starship its name. But his actual quest is for personal immortality, which puts him more in the territory of Tithonus. (And in the end it’s the Engineer who has his entrails devoured by a rather familiar vulture). The scientists, who travel across the galaxy to question their makers, are in another tradition entirely: an upside-down version of Job where questioning leads to the suffering instead of the other way around. The android David is in Pinocchio, and the android-like Meredith Vickers in King Lear. By the final act, it all begins to feel a bit like Jack and the Beanstalk, with the surviving Engineer as the giant: a big, scary monster to run away from. (In this it’s unfortunately more akin to the Predator than the lithe and devious xenomorphs. In either case, this is too great a diminution in importance: Perhaps we’re not supposed to think of the Engineers as gods, but they should be something more than horror-movie beasties.)

Prometheus succeeds as one of the few films to tackle the ground of SF stories about the exploration of a single alien world or artifact that may simply be outside the realm of human comprehension—stories like Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous With Rama or Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris. For all their physical similarity to us, the Engineers seem truly alien, at least until the last act. And though viewers and characters alike may speculate as to their reasons for creating the places and beings that we see, there ultimately may be no answers that could make sense to a human mind.

* A side note to anyone who was confused about the similarities (and notable differences) between the configuration of ships and deceased life forms at the end of Prometheus and the beginning of Alien: this is a different planet. Alien and Aliens occur on a planetoid called LV-426.

** This begs the rather large question of why they would have left instructions to our ancestors about how to find the planet from which this mission of annihilation was intended to launch. Chalk it up to rival factions among the Engineers, perhaps?

August 30, 2011

Doctor Who: Locking Hitler in the Cupboard

When the title card came up at the end of "A Good Man Goes to War," Doctor Who's last episode before the summer hiatus, I couldn't help but feel a bit of trepidation at what were no doubt intended to be thrilling words: "Let's Kill Hitler." After all, one of the central theses of everything I've written about Doctor Who over the last 8 years is that the Doctor doesn't kill anybody, no matter how bad they are. Those three words held a Damoclean sword over pretty much everything I have to say about Doctor Who and ethics.

When the title card came up at the end of "A Good Man Goes to War," Doctor Who's last episode before the summer hiatus, I couldn't help but feel a bit of trepidation at what were no doubt intended to be thrilling words: "Let's Kill Hitler." After all, one of the central theses of everything I've written about Doctor Who over the last 8 years is that the Doctor doesn't kill anybody, no matter how bad they are. Those three words held a Damoclean sword over pretty much everything I have to say about Doctor Who and ethics.

Imagine my relief, then, when those three words are uttered not by the Doctor, but by a hotheaded TARDIS-hijacker who is holding the Doctor at gunpoint. It's Amy and Rory's childhood friend Mels, not our erstwhile explorers themselves, who wants to right the greatest of wrongs with a bit of murder. The Doctor's peaceloving ways appear safe... for the time being.

It's surprising, given the anticipation this episode's title was meant to create and sustain, how quickly Hitler is dropped from the story. After a pretty brief showdown in the Fuhrer's office, he is locked in a cupboard-- literally, in that the Doctor wants to get him out of the way, and figuratively, in that the problem of Hitler has been pushed aside. And Hitler is, indeed, a problem for Doctor Who, as flashbacks through Mels' history emphasize. In her youth, Mels got in trouble in school for declaring that "a major factor in Hitler's rise to power was the fact that the Doctor didn't stop him"-- which got her sent to the principal's office. But in the universe of this show, she's right-- the Doctor didn't stop him. That's a problem that can't be locked in a cupboard as easily as the man himself was in this episode, and I can only hope that this scene wasn't the last word on the matter.

The rest of the episode suggests that this kind of conundrum is very much on the minds of the writers. The main baddie of this episode isn't Hitler himself, but the miniature crew of a robot doppelganger that travels through time pursuing and punishing war criminals-- doing, at first glance, what the Doctor can't, or won't. But we learn that their mission is not to prevent these war criminals from committing their atrocities, but rather simply to punish them at the ends of their lives, to "give them hell." This is a base form of retributive justice that can offer only the coldest of comforts. It's a kind of justice the Doctor has no interest in: it averts no atrocity; it soothes no grief; it simply offers a bureaucrat's sense of balance: this person caused pain, and received pain in return. The Doctor, naturally, wants no part of it.

In contrast to this is the Doctor's own mission in this episode, as he meets River Song at more-or-less the earliest point in her timeline that we have yet seen (not counting infancy, that is, or as-yet-to-be-revealed incarnations, or... oh, never mind). Originally, it seems, she was programmed to kill the Doctor, and that's what she's doing here. Moreover, we discover that, in the grand database of our miniaturized vigilante squad, River is considered the greatest war criminal in history. The Doctor doesn't want to punish her, or even to defeat her-- rather, he wants to remake this cruel, savage River into the hero we know she will become. That is the Doctor's brand of justice: transformation, rather than retribution.

But some facts can't be simply transformed. Hitler is still lurking in that cupboard... How will the Doctor deal with him when he gets out?

June 4, 2011

Do good Time Lords need rules?

[I'm going to go ahead and assume that, if you're reading this, you've seen "When a Good Man Goes to War." Meaning 1) I'm not going to bother with a summary, and 2) consider yourself spoiler-warned.]

Well, that sure was something. The last episode of Doctor Who before the mid-season break feels almost like a finale, answering as it does the biggest mystery of the last three years—who the heck River Song is.* It was great to see a greatest-hits type roundup of some of the neater minor characters, aliens, and neato costumes of the last few seasons, too. But most interesting to me was this exchange between the Doctor and mysterious-eyepatch-villain-lady Madame Kovarian:

Mme KOVARIAN: "Good men have too many rules."

THE DOCTOR: "Good men don't need rules… Today is not the day to find out why I have so many."

Moral implications within moral implications there: first, the concept of an innate moral imperative; the idea of an obtainable absolute good—and then, the revelation that the Doctor does not necessarily have that moral imperative, and that he has not obtained that absolute good.

Step back, then, and take a look at the army the Doctor has assembled to face down the military-church hybrid on Demons Run. (Yep, it's the same cleric-military from "The Time of Angels"—more on that later.) The Doctor has assembled some old friends, from the space pirates of "Curse of the Black Spot" to the Spitfire pilots of "Victory of the Daleks" to Dorium, the blue-skinned fence. There were a couple characters we haven't seen before, too: Madame Vastra, a sword-wielding Silurian from Victorian England, and Strax, a Sontaran warrior serving as a nurse as penance for an unknown offence.

The Doctor has worked with warriors before—heck, he spent years as a member of UNIT, which was basically the alien-fighting branch of the British Armed Forces. But his willingness to team up with Vastra—who we first see moments after she's eaten someone (sure, it was Jack the Ripper, but still) and who kills one of the Church's soldiers on Demons Run—poses an interesting moral conundrum. The Doctor has always shown an unwillingness to kill, or to participate in killing, no matter the purpose. For him, the ends have never justified the means. In "Genesis of the Daleks," he had the opportunity to destroy the first batch of Dalek mutants, thereby stopping the Daleks from ever being created and saving every life they would otherwise have taken—but he couldn't bring himself to kill. The 9th and 10th Doctor were fairly dark, as incarnations go, but that darkness was internal—it meant lots of brooding, not lots of violence. The 11th Doctor, for all his surface happy-go-luckiness, is a much more dangerous Doctor by far. In the opening story of this season, he essentially instructs the entire human race to murder the Silence—not to imprison them, or drive them away, but to kill them. And he does so by implanting a message in the film footage of the moon landing—writing violence into an image of peace and human achievement. And when the title card announcing the next episode states "Let's Kill Hitler"—well, one beigins to think that perhaps this Doctor might not have hesitated to kill that first batch of Daleks.

The Doctor has worked with warriors before—heck, he spent years as a member of UNIT, which was basically the alien-fighting branch of the British Armed Forces. But his willingness to team up with Vastra—who we first see moments after she's eaten someone (sure, it was Jack the Ripper, but still) and who kills one of the Church's soldiers on Demons Run—poses an interesting moral conundrum. The Doctor has always shown an unwillingness to kill, or to participate in killing, no matter the purpose. For him, the ends have never justified the means. In "Genesis of the Daleks," he had the opportunity to destroy the first batch of Dalek mutants, thereby stopping the Daleks from ever being created and saving every life they would otherwise have taken—but he couldn't bring himself to kill. The 9th and 10th Doctor were fairly dark, as incarnations go, but that darkness was internal—it meant lots of brooding, not lots of violence. The 11th Doctor, for all his surface happy-go-luckiness, is a much more dangerous Doctor by far. In the opening story of this season, he essentially instructs the entire human race to murder the Silence—not to imprison them, or drive them away, but to kill them. And he does so by implanting a message in the film footage of the moon landing—writing violence into an image of peace and human achievement. And when the title card announcing the next episode states "Let's Kill Hitler"—well, one beigins to think that perhaps this Doctor might not have hesitated to kill that first batch of Daleks.

And it is in this context that we learn that the Doctor does not consider himself a "good man"—that he has had to make rules for himself to keep him from crossing certain moral lines. Furthermore, we learn that the Doctor's actions have begun to affect galactic culture: the word "Doctor," in some languages, no longer means "healer," but rather "fierce warrior."** He is affecting the very language with which reality is described and stories are told. (This, I think, is the reason for the future military using ecclesiastical titles: the meaning of words, in this part of the future, can no longer be trusted.) And when is the last time we saw a great assembly of alien warriors including the Judoon and the Sontarans? …When all of the "bad guy" aliens teamed up to imprison the Doctor in the Pandorica. And that episode, too, played with the Doctor's moral position, depicting him as a mythological monster, "a nameless, terrible thing soaked in the blood of a billion galaxies, the most feared being in all the cosmos." I may be reading too much into things—I do tend to pay extraordinarily close attention to the Doctor's ethical decisions—but I think the Steven Moffat wants us to see the Doctor sliding away from his past morality and into murkier territory. Hmmm… Is the Valeyard on the horizon?

*I don't think it's bragging to say I had pretty much guessed it—but more specifically, I knew there had to be something going on with water names!

**Makes you wonder about Dr. River Song's honorific...

SF Gospel

- Gabriel Mckee's profile

- 21 followers