Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 258

March 29, 2018

a Holy Week thought on rhetorical Leninism

If you’re the kind of writer who works to be generous and fair-minded; if you admit that you have priors that incline you towards certain positions and away from others; if you’re willing to acknowledge that your preferred positions on a given issue are not without weaknesses, that there are trade-offs involved, and that those who choose the other side are not acting irrationally (even if you think they ultimately make the wrong call); then you should pursue that path only because you think it’s the right thing to do and not because you expect or even hope that people who disagree with you will extend similar courtesies to you. Because they almost certainly won’t.

Here’s a recent example: Michael Sean Winters reviewing Ross Douthat’s new book. Douthat exhibits all the traits I mentioned in the previous paragraph — I would call them “virtues,” though YMMV — and Winters, with the assurance characteristic of those who feel themselves enfolded by the wings of the Angels of Righteousness, announces his Judgment: Douthat’s “facts are nonsense, his arguments tendentious, and his thesis so absurd it is shocking, absolutely shocking, that no one over at Simon & Schuster thought to ask if what he writes is completely or only partially unhinged. I incline to the former adverb.” You can read further from there if you want; the review grows less restrained as it goes along.

Is Winters right? You will not be surprised to learn that I’m not convinced. (Even if didn’t call Ross a friend, I am always profoundly suspicious of declarations that definitive, whether they are positive or negative.) He quotes unnamed sources who say that Douthat is wrong, while ignoring Douthat’s own sources. He says that “thoughtful, learned churchmen” see things as he himself does — which I suppose leaves us to conclude that the churchmen Douthat quotes are neither thoughtful nor learned, though it seems to this observer that that point might profitably be debated. Again and again he assures us that there are no arguments for positions other than his own. I’m pretty sure that these matters are not as crystal-clear as Winters claims, but I don’t want to debate the substance here. What I am interested in, rather, is Winters’ scorched-earth approach.

It’s especially noteworthy, I think, that he simply ignores 95% of Douthat’s book, presumably because he doesn’t find anything in it to loathe. Which should remind us that, despite superficial appearances, what Winters has written is not a book review: it is a skirmish in a great War for the future of the Roman Catholic Church. And Winters quite evidently believes that the stakes of this war are such that generosity, or even elementary fairness, to one’s enemies is no virtue. The proper name for Winters’s strategy is rhetorical Leninism. “No mercy for these enemies of the people, the enemies of socialism, the enemies of the working people!” No mercy for the enemies of Pope Francis!

Always remember, those of you who strive for fairness and humility and charity and (yes) mercy: this is the coin in which you will surely be paid. And with that, a blessed Triduum to you all.

what philosophy is for

Jean-Paul Sartre was working furiously on his second play, Les Mouches (The Flies), while finishing his major philosophy treatise, L’Être et le néant (Being and Nothingness). Jean Paulhan had convinced Gallimard to publish the 700-page essay even if the commercial prospects were extremely limited. However, three weeks after it came out in early August, sales took off. Gallimard was intrigued to see so many women buying L’Être et le néant. It turned out that since the book weighed exactly one kilogram, people were simply using it as a weight, as the usual copper weights had disappeared to be sold on the black market or melted down to make ammunition.

— Agnès Poirier, via Warren Ellis

March 28, 2018

harmonic convergence

In one of my classes today I’m teaching the Dark Mountain Manifesto and in the other I’m teaching the Tao Te Ching, and let me tell you, the resonances between those two texts are extraordinary. So much to contemplate here. I find myself imagining a Daoist post-environmentalist Utopia….

children’s crusades

One clever little speciality of adult humans works like this: You very carefully (and, if you’re smart, very subtly) instruct children in the moral stances you’d like them to hold. Then, when they start to repeat what you’ve taught them, you cry “Out of the mouths of babes! And a little child shall lead them!” And you very delicately maneuver the children to the front of your procession, so that they appear to be leading it — but of course you make sure all along that you’re steering them in the way that they should go. It’s a social strategy with a very long history.

So, for instance, when you hear this:

“It’s the children who are now leading us,” said Diane Ehrensaft, the director of mental health for the clinic. “They’re coming in and telling us, ‘I’m no gender.’ Or they’re saying, ‘I identify as gender nonbinary.’ Or ‘I’m a little bit of this and a little bit of that. I’m a unique gender, I’m transgender. I’m a rainbow kid, I’m boy-girl, I’m everything.'”

— certain alarms should ring. No child came up with the phrase “I identify as gender nonbinary.” It is a faithful echo of an adult’s words.

Now, maybe you think it’s great that these children can begin to transition from one sex to another at an early age. I don’t, but I’m not going to argue that point now. My point is simply that if you say “It’s the children who are now leading us,” you’re lying — perhaps not consciously or intentionally, but it’s lying all the same because the truth is so easy to discern if you wish to do so. (As Yeats wrote, “The rhetorician would deceive his neighbors, / The sentimentalist himself.”)

This is why I think one of the most important books you could possibly read right now, if you care about these matters, is Richard Beck’s We Believe the Children: A Moral Panic in the 1980s. Beck is anything but a conservative — he’s an editor for n+1 — and his book is highly critical of traditionalist beliefs about families. And a “moral panic” might seem to be the opposite of the celebration of new openness to gender expressions and sexualities. But if you read Beck’s book you will see precisely the same cultural logic at work as we see in today’s children’s crusades.

In this “moral panic” of thirty years ago, social workers and, later, prosecutors elicited from children horrific tales of Satan-worship, sexual abuse, and murder — and then, when anyone expressed skepticism, cried “We believe the children!” But every single one of the stories was false. The lives of many innocent people, people who cared for children rather than exploiting or abusing them, were destroyed. And — this may be the worst of all the many terrifying elements of Beck’s story — those who, through subtle and not-so-subtle pressure, extracted false testimonies from children have suffered virtually no repercussions for what they did.

Moreover — and this is the point that I can’t stop thinking about — the entire episode has been erased from our cultural memory. Though it was headline news every day for years, virtually no one talks about it, virtually no one remembers it. Beck might as well be writing about something that happened five hundred years ago. And I think it has been suppressed so completely because no one wants to think that our good intentions can go so far astray. And if forced to comment, what would the guilty parties say? “We only did what we thought was best. We only believed the children.”

So if you want to celebrate the courage of trans tweens, or for that matter high-schoolers speaking out for gun control, please do. But can you please stop the pretense that “the children are leading us”? What you are praising them for is not courage but rather docility, for learning their lessons well. (I wonder if anyone who has praised the students who speak out on behalf of gun control has also praised the students who participate in anti-abortion rallies like the March for Life.) And perhaps you might also hope that, if things go badly for the kids whose gender transitions you are cheering for, your role will be as completely forgotten as those who, thirty years ago, sent innocent people to prison by doing only what they thought was best.

March 27, 2018

speaking truth to the professoriate

I’m probably going to write more about Scott Alexander’s take on Jordan Peterson, but for now I just want to note that he’s absolutely right to say that Peterson is playing a role that (a) most of us who teach the humanities say we already fill but (b) few of us care about at all:

Peterson is very conscious of his role as just another backwater stop on the railroad line of Western Culture. His favorite citations are Jung and Nietzsche, but he also likes name-dropping Dostoevsky, Plato, Solzhenitsyn, Milton, and Goethe. He interprets all of them as part of this grand project of determining how to live well, how to deal with the misery of existence and transmute it into something holy.

And on the one hand, of course they are. This is what every humanities scholar has been saying for centuries when asked to defend their intellectual turf. “The arts and humanities are there to teach you the meaning of life and how to live.” On the other hand, I’ve been in humanities classes. Dozens of them, really. They were never about that. They were about “explain how the depiction of whaling in Moby Dick sheds light on the economic transformations of the 19th century, giving three examples from the text. Ten pages, single spaced.” And maybe this isn’t totally disconnected from the question of how to live. Maybe being able to understand this kind of thing is a necessary part of being able to get anything out of the books at all.

But just like all the other cliches, somehow Peterson does this better than anyone else. When he talks about the Great Works, you understand, on a deep level, that they really are about how to live. You feel grateful and even humbled to be the recipient of several thousand years of brilliant minds working on this problem and writing down their results. You understand why this is all such a Big Deal.

March 25, 2018

hope

When I see young people out there marching and demonstrating and making their voices heard on behalf of causes I already believe in, wow, does that give me hope for the future. There are few experiences in this vale of tears that lift my heart like watching the youth of our nation so vigorously confirming all my priors. Now, to be sure, sometimes they speak up on behalf of causes that I don’t believe in, in which case it’s totally pathetic how their parents and other authority figures so shamelessly use kids to promote their own agendas. But as long as those future voters agree with me, they’re a shining beacon for our nation. As I say every time their politics match mine: The kids are all right.

March 23, 2018

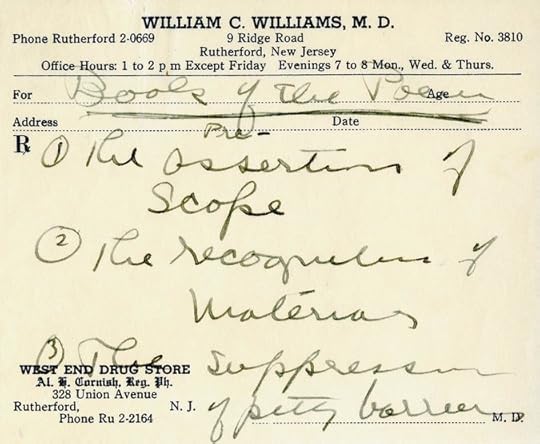

Prescription: Poem

The History of Life Through Time

Austin Kleon’s post about his son Owen’s book — finished before Dad’s book has even put its pants on — reminds me of this conversation I had with my son Wesley when he was six:

http://blog.ayjay.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Wes-10.8.99.m4a

March 20, 2018

Levi van Veluw: Veneration

exegetical puzzlement

Much of Paul Baumann’s review of Ross Douthat’s new book is devoted to intra-Catholic disputes that I won’t presume to adjudicate, but there’s one passage that strikes me as extremely odd:

Douthat is right about Jesus’ intransigence regarding marriage in Mark’s Gospel : “What God has joined together, let no one put asunder” (10:9). Matthew, however, finds this teaching too hard, and exercising his authority as an Apostle, an authority conferred by Jesus, grants an exception for “unchastity” (5:32; 19:9).

Now, the passages Baumann cites are from extended teachings by Jesus. So Baumann’s interpretation of those passages is that when Matthew claims to be reporting what Jesus said, what he’s actually doing is presenting his own teaching about marriage — but that’s okay because his authority to do so was conferred on him by Jesus. Which is one of the more peculiar bits of exegesis I have ever come across.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers