Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 261

February 28, 2018

biblioteca

well, back to work

February 24, 2018

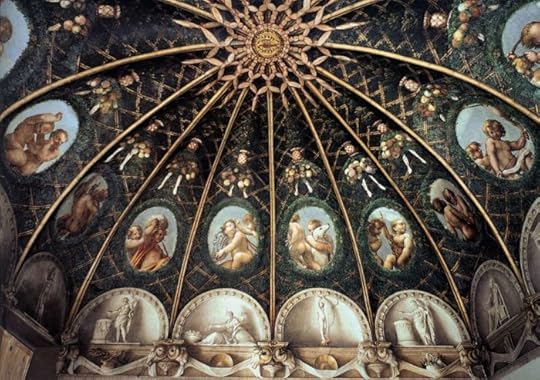

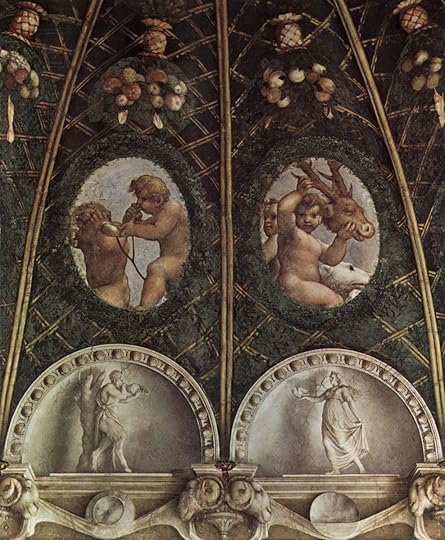

Correggio’s deception

It being lawful to paint then, is it lawful to paint everything? So long as the painting is confessed—yes; but if, even in the slightest degree, the sense of it be lost, and the thing painted be supposed real—no…. In the Camera di Correggio of San Lodovico at Parma, the trellises of vine shadow the walls, as if with an actual arbor; and the troops of children, peeping through the oval openings, luscious in color and faint in light, may well be expected every instant to break through, or hide behind the covert. The grace of their attitudes, and the evident greatness of the whole work, mark that it is painting, and barely redeem it from the charge of falsehood; but even so saved, it is utterly unworthy to take a place among noble or legitimate architectural decoration.

— Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Unique to Ruskin is the combination of an exceptionally acute aesthetic sense with an exceptionally acute moral sense, and this is one of the many moments when they struggle mightily against each other. Ruskin cannot help admiring the beauty of Correggio’s work here, but he is so deeply opposed to deception in art that he wishes he could reject it altogether.

house

February 23, 2018

some clarifications

Over at Mere Orthodoxy, Jake Meador responds to this post of mine — but I believe Jake misunderstands what my post is about. He reflects at some length on “mere Christianity” idea and whether it is tenable, or whether by contrast it can compromise the strength of particular traditions — but I don’t say anything about that in my post. Jake goes on to say that “Dr. Jacobs seems to suggest that there is an old First Things that essentially lived exclusively in the living room of the Mere Christianity house” — but I didn’t suggest that and I don’t think it. FT was at its best a place where people from different traditions in Christianity and Judaism (and even, very occasionally, Islam) could engage in serious conversation with one another, and what made the conversation serious was the fact that the participants held firm to the convictions arising from their traditions, even when those convictions separated them in some ways from other participants.

The point of my post is much simpler: if a magazine claims to be “interreligious” and yet (a) is run completely by people in one wing of one religion and (b) publishes essays that defend the claims of that tradition over against all the other traditions supposedly represented in the magazine, but never publishes essays that call that preferred tradition into equally serious question, then there is a dissonance between what the magazine says it is and what it actually is. That’s all I am saying.

One more point: Jake says that Comment is Reformed and has a Reformed “spin” on things, but I am not Reformed, and I believe that there are other members of the editorial board who would not describe themselves as Reformed either. So I think Comment at least has the possibility of becoming more genuinely ecumenical than the “Reformed” moniker would suggest.

text three ways

When my buddy Austin Kleon posted his notebook turducken I realized that I have a three-part system too, though a somewhat different one:

I use a small Moleskine planner for my calendar and tasks, a Leuchtturm notebook for ideas and drafts, and index cards for reading notes (including notes I make for the books I teach). It would of course be possible to put all of this in one notebook, but such simplification would come at too high a price. For instance, with my current system I have a place where I keep track of my events and tasks for an entire year, but if I did that in the notebook where I also write drafts, then when that notebook was full I’d have to make a new calendar no matter what point in the year I’m at — and then lose ready access to the old calendar. Similarly, when I have reading notes on index cards, I can spread them out and look at them as I’m writing drafts, which is much better than having to turn back and forth to multiple pages in multiple notebooks.

February 19, 2018

On Erik Stevens

I am breaking my Lenten silence because (a) I am a poor excuse for a Christian and (b) I can’t stop thinking about Black Panther. The movie had some flaws — chief among them, I think, the exceptionally poor CGI, which is really unforgivable in a film that depends so much on CGI — but the story is the strongest, most coherent, and most meaningful one of any film in the MCU.

But you know what could have made it even better?

Let’s consider Erik Killmonger for a moment: a man whose justifiable rage at injustice (against him and against the world’s black people) has turned him into a psychopath. We see him kill several people he doesn’t have to kill, and Lord knows how many more of those there are in his past. He is, as T’Challa says, a monster (and, as T’Challa also says, one of Wakanda’s own making). But what if he weren’t a monster?

Imagine an Erik Stevens with all of the same warrior’s skills and commitment to justice who channels his rage into strategy. Who understands the fear of the ruling families of Wakanda and seeks to win them, and the people as a whole, over to his side. Who has a dream, a dream of liberation for black people around the world, and of Wakanda as the agent of that liberation — and who can powerfully and passionately articulate that dream.

He’s never going to win over Shuri, of course. But while she may be the only supergenius, she’s not the only brilliant scientist/technologist in Wakanda. Others might well rally to King N’Jadaka, seeing his plan as one that could make them famous and influential — could make them, literally, world-changers. The new King would also have the Dora Milaje on his side — something even Killmonger manages, before he throws that boon away — which would be a powerful visual manifestation of his kingship.

What then? Could T’Challa hope to reclaim his throne when such a king has claimed it, and, according to the laws of Wakanda, rightfully claimed it? Would he not go down in Wakanda’s history as the weak son of a weak king, capable of no more than scrabbling to preserve Wakanda’s secret wealth, lacking compassion for the world’s oppressed black peoples, lacking the vision to bring Wakanda to its proper place on the world stage, as a king among nations?

That probably wouldn’t be good for the MCU franchise, of course (though I can imagine some interesting possibilities). But maybe T’Challa as tragic hero, destroyed by Nemesis, would be the best T’Challa of all.

February 13, 2018

three things

February 12, 2018

religion and public life revisited

I’m late to this party, but there’s something to be said for taking time to think things over. The already-much-discussed book review in First Things by Romanus Cessario, in which Cessario defends the kidnapping of a Jewish child by Pope Pius IX, raises many important issues, and I want to focus on just one of them here. But first some clarifications.

First of all, there can be no question that Cessario is not simply defending Pio Nono’s action within the context of the governance of the Papal States, but is also laying down a more general principle. Thus:

No one who considers the Mortara affair can fail to be moved by its natural dimensions. It is a grievous thing to sever familial bonds. But the honor we give to mother and father will be imperfect if we do not render a higher honor to God above. Christ’s authority perfects all natural institutions — the family as well as the state. This is why he said that he came bearing a sword that would sunder father and son. One’s judgment of Pius will depend on one’s acceptance of Christ’s claim.

The lesson is clear: If you accept Christ’s claim, you will support Pius’s decision; if you do not support Pius’s decision, then you are ipso facto denying, or at the very best questioning, “Christ’s claim.” Cessario reaffirms this view when he says, in his last paragraph, “Those examining the Mortara case today are left with a final question: Should putative civil liberties trump the requirements of faith?” Civil liberties are merely “putative”; Pio Nono acted in accordance with the requirements of faith. He could do no other and be faithful to his vocation and his office. And the “claim of Christ,” and the consequent “requirements of faith,” surely do not change from time to time and place to place. (Note that Cessario does not have any questions to pose to those who support Pio Nono’s actions.)

A second point of clarification: As Robert T. Miller points out in this post, that Edgardo Mortaro was Jewish is culturally significant, in that time and place and perhaps in ours as well, but theologically not to the point. For doctrinally speaking what underlies Pius’s action was not the fact that Mortara was ethnically Jewish but the fact that his family was not Catholic.

The operative assumption in Cessario’s argument is not that the child’s parents were Jewish but that they could not reasonably be expected to give the child a Catholic upbringing and education. Hence, if it is right to terminate the custodial rights of Jewish parents if their child somehow gets baptized, it will be right to do the same to parents who are pagans, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, atheists, or — it certainly seems — Protestants and even fallen-away Catholics. I don’t deny that, as a historical matter, the Mortaras were treated so badly because they were Jewish — of course, they were. I mean only that Cessario’s argument to justify Pius’s actions in the case would, by its terms, apply to many parents other than Jewish ones, and it helps in keeping the analysis clear to think in the broader terms in which that argument is cast.

Miller concludes his post by asking Rusty Reno, the editor of Fist Things, to “disavow the position Cessario takes on the Mortara case and to reaffirm the journal’s historical commitment to the freedom of religion as understood in liberal states.”

Writing in response, Rusty very straightforwardly does the former: “The Edgardo Mortara episode is a stain on the Catholic Church. Whatever one thinks about the efficacy of baptism, forcibly separating a child from his parents is a grievous act. And even if one can construct a theoretical rationale for doing so, as Romanus Cessario does, it was wildly imprudent of Pius IX to take Edgardo from his parents, given the scandal it brought upon the Catholic Church, a scandal that continues to this day.” The latter request he does not explicitly address, though much of his post does so implicitly.

However, Rusty certainly does not apologize for running Cessario’s review. He argues rather that “Cessario, however, wants to challenge me. I must not imagine complacently that my natural moral sentiments and the modern liberal principles I endorse will always happily correspond with the demands that flow from ‘the reality of the Lord’s things.’” He adds, further, that “Cessario, a priest, is perhaps more perceptive that I am about our spiritual challenges” — which, for what it’s worth, I do not read as a qualification of his repudiation of Pius’s action, though I suppose some have taken it as such.

Rusty goes on, quite movingly, to describe his own family situation: his wife is Jewish and his children have been raised as Jews, and going to church alone has been his portion for many years now. So in this light you can see what he means, and that what he means is quite powerful, when he says that Cessario wants to challenge him.

And yet, it should be said — and I hope I can say it without seeming to minimize the painful complexities that Rusty has experienced — that the challenge that Cessario poses to people who, like Rusty, already believe that the Pope stands at the head of the One True Church is different, and less offensive, than the challenge it offers to non-Catholic Christians; and that challenge is less scandalous still than the one Cessario poses to non-Christians — primarily, though not only, Jews.

Which leads me, finally, to the one point I want to make. Imagine that I, an Anglican, were the editor of First Things, and I published an essay by a priest of the Church of England arguing that Elizabeth I was perfectly justified in carrying out her lengthy persecution of English Catholics, since she was ordained by God as His royal servant implementing the True Biblical Faith in England, and the Roman Catholic Church by contrast is the Whore of Babylon as described in the Revelation to John. Imagine further that I responded to criticism by saying that I don’t agree with that argument but find that it challenges me in salutary ways. Would Catholic readers of the magazine be mollified by that explanation? I suspect not — even if my wife were a Catholic and my children were being raised in that communion.

Of course, the real-world First Things would never run such an essay, any more than it would run an essay by a Muslim arguing that the right and proper place of Christians and Jews in the world is dhimmitude under a restored Caliphate, or one by a Jew arguing that Christianity in all its forms is necessarily and intrinsically anti-Semitic and should therefore be repudiated and marginalized by all right-thinking people. As I have noted several times on this blog and elsewhere, the Overton window of acceptable positions for First Things articles has been moving for several years now, but moving in only one direction: towards an increasing acceptance of the claims of the Roman Catholic Church over against other religious communities. Whether it might be defensible for non-Catholics to be in a position of dhimmitude vis-a-vis Catholicism is a question to be asked in the pages of First Things; but the legitimacy of Catholicism is never similarly open to question. For some time now it has been quite clear who at First Things are the first-class citizens and who need to make their way the back of the cabin. And this cannot be surprising, given that the entire editorial staff of the journal, as far as I tell, is Roman Catholic.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that. But the Institute on Religion and Public Life, which publishes First Things, describes itself as “an interreligious, nonpartisan research and educational 501(c)(3) organization.” To what extent can the Institute’s flagship publication be “interreligious” when its entire staff belongs not just to one religion but one communion within that religion? Certain questions about “religion and public life” — First Things calls itself “a journal of religion and public life” — will perforce be explored narrowly and (I think) in limited ways if one religious communion always takes the role of arbiter, if its core commitments are always considered normative while others’ fall under deeper scrutiny.

I have made arguments similar to this one before, and they haven’t been heeded or even acknowledged. But is is precisely because I believe in the stated mission of First Things, and regret its dramatically constrained current understanding of that mission, that I have become involved with Comment, which I believe is trying, in its currently small way, to take up the torch that First Things has, in my judgment, dropped. But I would be very pleased if First Things would pick it up also and we could carry it together.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers