Steve Blank's Blog, page 54

March 15, 2011

The LeanLaunch Pad at Stanford – Class 2: Business Model Hypotheses

Our new Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment in a new model of teaching startup entrepreneurship. This post is part two. Part one is here. Syllabus here.

By now the nine teams in our Stanford Lean LaunchPad Class were formed, In the four days between team formation and this class session we tasked them to:

Write down their initial hypotheses for the 9 components of their company's business model (who are the customers? what's the product? what distribution channel? etc.)

Come up with ways to test each of the 9 business model canvas hypotheses

Decide what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test. At what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct?

Consider if their business worth pursuing? (Give us an estimate of market size)

Start their team's blog/wiki/journal to record their progress during for the class

The Nine Teams Present

Each week every team presented a 10 minute summary of what they had done and what they learned that week. As each team presented, the teaching team would ask questions and give suggestions (at times pointed ones) for things the students missed or might want to consider next week. (These presentations counted for 30% of their grade. We graded them on a scale of 1-5, posted our grades and comments to a shared Google doc, and had our Teaching Assistant aggregate the grades and feedback to pass on to the teams.)

Our first team up was Autonomow. Their business was a robot lawn mower. Off to a running start, they not only wrote down their initial business model hypotheses but they immediately got out of the building and began interviewing prospective customers to test their three most critical assumptions in any business:

Value Proposition, Customer Segment and Channel. Their hypotheses when they first left the campus were:

Value Proposition: Labor costs in mowing and weeding applications are significant, and autonomous implementation would solve the problem.

Customer Segment: Owners/administrators of large green spaces (golf courses, universities, etc.) would buy an autonomous mower. Organic farmers would buy if the Return On Investment (ROI) is less than 1 year.

Channel: Mowing and agricultural equipment dealers

All teams kept a blog – almost like a diary – to record everything they did. Reading the Autonomow blog for the first week, you could already see their first hypotheses starting to shift: "For mowing applications, we talked to the Stanford Ground Maintenance, Stanford Golf Course supervisor for grass maintenance, a Toro distributor, and an early adopter of an autonomous lawn mower. For weeding applications, we spoke with both small and large farms. In order from smallest (40 acres) to largest (8000+ acres): Paloutzian Farms, Rainbow Orchards, Rincon Farms, REFCO Farms, White Farms, and Bolthouse Farms."

"We got some very interesting feedback, and overall interest in both systems," reported the team. "Both hypotheses (mowing and weeding) passed, but with some reservations (especially from those whose jobs they would replace!) We also got good feedback from Toro with respect to another hypothesis – selling through distributor vs. selling direct to the consumer."

The Autonomow team summarized their findings in their first 10 minute, weekly Lesson Learned presentation to the class.

Our feedback: be careful they didn't make this a robotics science project and instead make sure they spent more time outside the building.

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here.

Autonomow team members:

Jorge Heraud (MS Management, 2011) Business Unit Director, Agriculture, Trimble Navigation, Director of Engineering, Trimble Navigation, MS&E (Stanford), MSEE (Stanford), BSEE (PUCP, Peru)

Lee Redden (MSME Robotics, Jun 2011) Research in haptic devices, autonomous systems and surgical robots, BSME (U Nebraska at Lincoln), Family Farms in Nebraska

Joe Bingold (MBA, Jun 2011) Head of Product Development for Naval Nuclear Propulsion Plant Control Systems, US Navy, MSME (Naval PGS), BSEE (MIT), P.E. in Control Systems

Fred Ford (MSME, Mar 2011) Senior Eng for Mechanical Systems on Military Satellites, BS Aerospace Eng (U of Michigan)

Uwe Vogt (MBA, Jun 2011) Technical Director & Co-Owner, Sideo Germany (Sub. Vogt Holding), PhD Mechanical Engineering (FAU, Germany), MS Engineering (ETH Zurich, Switzerland

The mentors who volunteered to help this team were Sven Strohbad, Ravi Belani and George Zachary.

Personal Libraries

Our next team up was Personal Libraries which proposed to help researchers manage, share and reference the thousands of papers in their personal libraries. "We increase a researcher's productivity with a personal reference management system that eliminates tedious tasks associated with discovering, organizing and citing their industry readings," wrote the team. What was unique about this team was that Xu Cui, a Stanford postdoc in Neuroscience, had built the product to use for his own research. By the time he joined the class, the product was being used in over a hundred research organizations including Stanford, Harvard, Pfizer, the National Institute of Health and Peking University. The problem is that the product was free for end users and few Research institutions purchased site licenses. The goal was to figure out whether this product could become a company.

The Personal Libraries core hypotheses were:

We solve enough pain for researchers to drive purchase

Dollar size of deals is sufficient to be profitable with direct sales strategy

The market is large enough for a scalable business

Our feedback was that "free" and "researchers in universities" was often the null set for a profitable business.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

Personal Libraries Team Members

Abhishek Bhattacharyya (MSEE, Jun 2011) creator of WT-Ecommerce, an open source engine, Ex-NEC engineer

Xu Cui (Ph.D, Jun 2007 Baylor) Stanford Researcher Neuroscience, postdoc, BS biology from Peking University

Mike Dorsey (MBA/MSE, Jun 2011) B.S. in computer science, environmental engineering and middle east studies from Stanford, Austin College and the American University in Cairo

Becky Nixon (MSE, Jun 2011) BA mathematics and psychology Tulane University Ex-Director, Scion Group,

Ian Tien (MBA, Jun 2011) MS in Computer Science from Cornell, Microsoft Office Engineering Manager for SharePoint, and former product manager for SkyDrive

The mentors who volunteered to help this team were Konstantin Guericke and Bryan Stolle.

The Week 2 Lecture: Value Proposition

Our working thesis was not one we shared with the class – we proposed to teach entrepreneurship the way you would teach artists – deep theory coupled with immersive hands-on experience.

Our lecture this week covered Value Proposition – what problem will the customer pay you to solve? What is the product and service you were offering the customer to solve that problem.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

Feeling Good

Seven other teams presented after the first two (we'll highlight a few more of them in the next posts.) About half way through the teaching team started looking at each other all with the same expression – we may be on to something here.

———

Next week each team tests their value proposition hypotheses (their product/service) and reports the results of face-to-face customer discovery. Stay tuned

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

March 14, 2011

The Lean LaunchPad Class at Stanford: Class 2- Business Model and Customer Discovery Hypotheses

Our new Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment in teaching a new model of startup entrepreneurship. This post is part two.

By now the nine teams at our Stanford Lean LaunchPad Class were formed, and in the four days between the team formation and this class session we tasked them to:

Write down the hypotheses for the 9 parts of their company's business model.

Come up with ways to test:

each of the 9 business model hypotheses

is their business worth pursuing (give us an estimate of market size)

Come up with what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test (e.g. at what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct)?

Start their blog/wiki/journal for the class

The Nine Teams Present

Every week every team had to present a 10 minute summary of what they did and what they learned. As each team presented the teaching team would ask questions and give suggestions (at times pointed ones) for things they missed or might want to consider next week. (These presentations counted for 30% of their grade, and graded them on a scale of 1-5, posted our grades and comments to a shared Google doc, and had our Teaching Assistant aggregate the grades and feedback to pass on to the teams.)

Our first team up was Autonomow. They were going to develop a robot lawn mower. Off to a running start, they not only wrote down their initial business model hypotheses but they immediately got out of the building and began interviewed prospective customers to test their three most critical assumptions in any business: Value Proposition, Customer Segment and Channel. Their hypotheses when they left the campus were:

Value Proposition: Labor costs in mowing and weeding applications are significant, and autonomous implementation would solve the problem.

Customer Segment: Owners/administrators of large green spaces (golf courses, universities, etc.) would buy an autonomous mower. Organic farmers would buy if the Return On Investment (ROI) is less than 1 year.

Channel: Mowing and agricultural equipment dealers

All teams were keeping a blog – almost like a diary – of what they were doing. Reading the Autonomow blog for the first week was interesting, you could see their first hypotheses already starting to shift: "For mowing applications, we talked to the Stanford Ground Maintenance, Stanford Golf Course supervisor for grass maintenance, a Toro distributor, and an early adopter of an autonomous lawn mower. For weeding applications, we spoke with both small and large farms. In order from smallest (40 acres) to largest (8000+ acres): Paloutzian Farms, Rainbow Orchards, Rincon Farms, REFCO Farms, White Farms, and Bolthouse Farms.

We got some very interesting feedback, and overall interest in both systems. Both hypotheses (mowing and weeding) passed, but with some reservations (especially from those who's jobs they would replace!) We also got good feedback from Toro with respect to another hypothesis – selling through distributor vs. selling direct to the consumer."

The Autonomow team summarized their findings in their first 10 minute, weekly Lesson Learned presentation to the class.

Autonomow team members:

Jorge Heraud (MS Management, 2011) Business Unit Director, Agriculture, Trimble Navigation, Director of Engineering, Trimble Navigation, MS&E (Stanford), MSEE (Stanford), BSEE (PUCP, Peru)

Lee Redden (MSME Robotics, Jun 2011) Research in haptic devices, autonomous systems and surgical robots, BSME (U Nebraska at Lincoln), Family Farms in Nebraska

Joe Bingold (MBA, Jun 2011) Head of Product Development for Naval Nuclear Propulsion Plant Control Systems, US Navy, MSME (Naval PGS), BSEE (MIT), P.E. in Control Systems

Fred Ford (MSME, Mar 2011) Senior Eng for Mechanical Systems on Military Satellites, BS Aerospace Eng (U of Michigan)

Uwe Vogt (MBA, Jun 2011) Technical Director & Co-Owner, Sideo Germany (Sub. Vogt Holding), PhD Mechanical Engineering (FAU, Germany), MS Engineering (ETH Zurich, Switzerland

Personal Libraries

Our next team up was Personal Libraries. They wanted to help researchers manage, share and reference the thousands of papers in their personal libraries. We increase a researcher's productivity with a personal reference management system that eliminates tedious tasks associated with discovering, organizing and citing their industry readings. What was unique about this team was that Xu Cui a Stanford postdo in Neuroscience had built the product to use for his own research. By the time he joined the class it was being used in over a hundred research organizations including Stanford, Harvard, Pfizer, the National Institute of Health and Peking University. The problem is that the product is free to use for end users and few Research institutions purchased site licenses. The goal was to figure out whether this product could become a company.

The Personal Libraries core hypotheses are:

We solve enough pain for researchers to drive purchase

Dollar size of deals sufficient to be profitable with direct sales strategy

The market large enough for a scalable business

Personal Libraries Team Members

Abhishek Bhattacharyya, creator of WT-Ecommerce, an open source engine, Ex-NEC engineer, Masters EE candidate

Xu Cui Stanford Researcher Neuroscience, postdoc, PhD in Neuroscience from Baylor College of Medicine and a degree in biology from Peking University

Mike Dorsey B.S. in computer science, environmental engineering and middle east studies from Stanford, Austin College and the American University in Cairo MS/MBA candidate

Becky Nixon BA mathematics and psychology Tulane University Ex-Director, Scion Group, Stanford MS&E candidate

Ian Tien . MS in Computer Science from Cornell, Microsoft Office Engineering Manager for SharePoint, and former product manager for SkyDrive , Stanford MBA/MPP candidate

Teaching Team Week 2 Lecture: Value Proposition

Our working thesis was not one we shared with the class – we proposed to teach entrepreneurship like you would teach artists – deep theory plus immersive hands-on.

Our lecture this week covered Value Proposition – what problem is the customer going to pay you to solve? What product and service you were offering the customer to solve that problem.

———

Deliverable for Jan 18th:

Find a name for your team.

What were your value proposition hypotheses?

What did you discover from customers?

Submit interview notes, present results in class.

Update your blog/wiki/journal

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching

March 8, 2011

A New Way to Teach Entrepreneurship – The Lean LaunchPad at Stanford: Class 1

For the past three months, we've run an experiment in teaching entrepreneurship.

In January, we introduced a new graduate course at Stanford called the Lean LaunchPad. It was designed to bring together many of the new approaches to building a successful startup – customer development, agile development, business model generation and pivots.

We thought it would be interesting to share the week-by-week progress of how the class actually turned out. This post is part one.

A New Way to Teach Entrepreneurship

As the students filed into the classroom, my entrepreneurial reality distortion field began to weaken. What if I was wrong? Could we even could find 40 Stanford graduate students interested in being guinea pigs for this new class? Would anyone even show up? Even if they did, what if the assumption – that we had developed a better approach to teaching entrepreneurship – was simply mistaken?

We were positing that 20 years of teaching "how to write a business plan" might be obsolete. Startups, are not about executing a plan where the product, customers, channel are known. Startups are in fact only temporary organizations, organized to search–not execute–for a scalable and repeatable business model.

We were going to toss teaching the business plan aside and try to teach engineering students a completely new approach to start companies – one which combines customer development, agile development, business models and pivots. (The slides below and the syllabus here describe the details of the class.)

Get Out of the Building and test the Business Model

While we were going to teach theory and frameworks, these students were going to get a hands-on experience in how to start a new company. Over the quarter, teams of students would put the theory to work, using these tools to get out of the building and talk to customer/partners, etc. to get hard-earned information. (The purpose of getting out of the building is not to verify a financial model but to hypothesize and verify the entire business model. It's a subtle shift but a big idea with tremendous changes in the end result.)

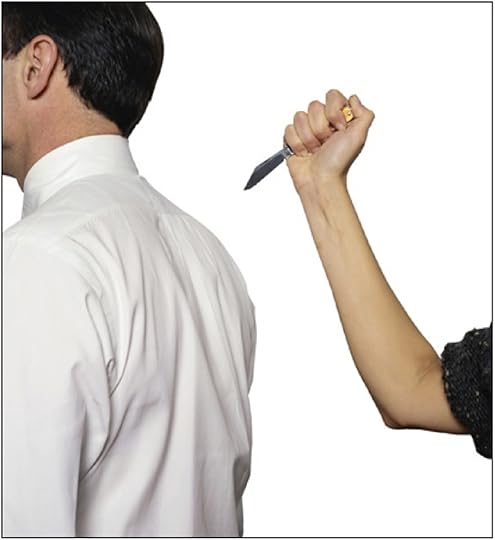

Team Autonomow: Weeding Robot Prototype on a Farm

We were going to teach entrepreneurship like you teach artists – combining theory – with intensive hands-on practice. And we were assuming that this approach would work for any type of startup – hardware, medical devices, etc. – not just web-based startups.

If we were right, we'd see the results in their final presentations – after 8 weeks of class the information/learning density in the those presentations should be really high. In fact they would be dramatically different than any other teaching method.

But we could be wrong.

While I had managed to persuade two great VC's to teach the class with me (Jon Feiber and Ann Miura-ko), what if I was wasting their time? And worse, what if I was going to squander the time of my students?

I put on my best game face and watched the seats fill up in the classroom.

Mentors

A few weeks before the Stanford class began, the teaching team went through their Rolodexes and invited entrepreneurs and VCs to volunteer as coaches/mentors for the class's teams. (Privately I feared we might have more mentors than students.) An hour before this first class, we gathered these 30 impressive mentors to brief them and answer questions they might have after reading the mentor guide which outlined the course goals and mentor responsibilities.

As the official start time of the first class drew near, I began to wonder if we had the wrong classroom. The room had filled up with close to a 100 students who wanted to get in. When I realized they were all for our class, I could start to relax. OK, somehow we got them interested. Lets see if we can keep them. And better, lets see if we can teach them something new.

The First Class

The Lean LaunchPad class was scheduled to meet for three hours once a week. Given Stanford's 10 week quarters, we planned for eight weeks of lecture and the last two weeks for team final presentations. Our time in class would be relatively straightforward. Every week, each team would give a 10-minute presentation summarizing the "lessons learned" from getting out of the building. When all the teams were finished the teaching team lectured on one of the 9 parts of the business model diagram. The first class was an introduction to the concepts of business model design and customer development.

http://www.slideshare.net/sblank/stan...

The most interesting part of the class would happen outside the classroom when each team spent 50-80 hours a week testing their business model hypotheses by talking to customers and partners and (in the case of web-based businesses) building their product.

Selection, Mixer and Speed Dating

After the first class, our teaching team met over pizza and read each of the 100 or so student applications. Two-thirds of the interested students were from the engineering school; the other third were from the business school. And the engineers were not just computer science majors, but in electrical, mechanical, aerospace, environmental, civil and chemical engineering. Some came to the class with an idea for a startup burning brightly in their heads. Some of those applied as teams. Others came as individuals, most with no specific idea at all.

We wanted to make sure that every student who took the class had at a minimum declared a passion and commitment to startups. (We'll see later that saying it isn't the same as doing it.) We tried to weed out those that were unsure why they were there as well as those trying to build yet another fad of the week web site. We made clear that this class wasn't an incubator. Our goal was to provide students with a methodology and set of tools that would last a lifetime – not to fund their first round. That night we posted the list of the students who were accepted into the class.

The next day, the teaching team held a mandatory "speed-dating" event with the newly formed teams. Each team gave each professor a three-minute elevator pitch for their idea, and we let them know if it was good enough for the class. A few we thought were non-starters were sold by teams passionate enough to convince us to let them go forward with their ideas. (The irony is that one of the key tenets of this class is that startups end up as profitable companies only after they learn, discover, iterate and Pivot past their initial idea.) I enjoyed hearing the religious zeal of some of these early pitches.

The Teams

By the beginning of second session the students had become nine teams with an amazing array of business ideas. Here is a brief summary of each.

Agora isan affordable "one-stop shop" for cloud computing needs. Intended for cloud infrastructure service providers, enterprises with spare capacity in their private clouds, startups, companies doing image and video processing, and others. Agora's selling points are its ability to reduce users' IT infrastructure cost and enhance revenue for service providers.

Autonomow is an autonomous large-scale mowing intended to be a money-saving tool for use on athletic fields, golf courses, municipal parks, and along highways and waterways. The product would leverage GPS and laser-based technologies and could be used on existing mower or farm equipment or built into new units.

BlinkTraffic will empower mobile users in developing markets (Jakarta, Sao Paolo, Delhi, etc.) to make informed travel decisions by providing them with real-time traffic conditions. By aggregating user-generated speed and location data, Blink will provide instantaneously generated traffic-enabled maps, optimal routing, estimated time-to-arrival and predictive itinerary services to personal and corporate users.

D.C. Veritas is making a low cost, residential wind turbine. The goal is to sell a renewable source of energy at an affordable price for backyard installation. The key assumptions are: offering not just a product, but a complete service (installation, rebates, and financing when necessary,) reduce the manufacturing cost of current wind turbines, provide home owners with a cool and sustainable symbol (achieving "Prius" status.)

JointBuy is an online platform that allows buyers to purchase products or services at a cheaper price by giving sellers opportunities to sell them in bulk. Unlike Groupon which offers one product deal per day chosen based on the customer's location. JointBuy allows buyers to start a new deal on any available product and share the idea with others through existing social networking sites. It also allows sellers to place bids according to the size of the deal.

MammOptics is developing an instrument that can be used for noninvasive breast cancer screening. It uses optical spectroscopy to analyze the physiological content of cells and report back abnormalities. It will be an improvement over mammography by detecting abnormal cells in an early stage, is radiation-free, and is 2-5 times less expensive than mammographs. We will sell the product directly to hospitals and private doctors.

Personal Libraries is a personal reference management system streamlinig the processes for discovering, organizing and citing researchers' industry readings. The idea came from seeing the difficulty biomed researchers have had in citing the materials used in experiments. The Personal Libraries business model is built on the belief that researchers are overloaded with wasted energy and inefficiency and would welcome a product that eliminates the tedious tasks associated with their work.

PowerBlocks makes a line of modular lighting. Imagine a floor lamp split into a few components (the base, a mid-section, the top light piece). What would you do if wanted to make that lamp taller or shorter? Or change the top light from a torch-style to an LED-lamp? Or add a power plug in the middle? Or a USB port? Or a speaker? "PowerBlocks" modular lighting is "floor-lamp meets Legos" but much more high-end. Customers can choose components to create the exact product that fit their needs.

Voci.us is an ad-supported, web-based comment platform for daily news content. Real-time conversations and dynamic curation of news stories empowers people to expand their social networks and personal expertise about topics important to them. This addresses three problems vexing the news industry: inadequate online community engagement, poor topical search capacity on news sites, and scarcity of targeted online advertising niches.

While I was happy with how the class began, the million dollar question was still on the table – is teaching entrepreneurship with business model design and customer development better than having the students write business plans? Would we have to wait 8 more weeks until their final presentation to tell? Would we signs of success early? Or was the business model/customer development framework just smoke, mirror and B.S.?

The Adventure Begins

We're going to follow the adventures of a few of the teams week by week as they progressed through the class, (and we'll share the teams weekly "lessons learned," as well as our class lecture slides.

The goal for the teams for next week were:

Write down their hypotheses for each of the 9 parts of the business model.

Come up with ways to test:

what are each of the 9 business model hypotheses?

is their business worth pursuing (market size)

Come up with what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test (e.g. at what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct)?

Start their blog/wiki/journal for the class

Next Post: The Business Model and Customer Discovery Hypotheses – Class 2

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching

March 2, 2011

Honor and Recognition in Event of Success

"Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success."

Attributed to Ernest Shackleton

In 1912 Ernest Shackleton placed this ad to recruit a crew for the ship Endurance and his expedition to the South Pole. This would be one of the most heroic journeys of exploration ever undertaken. In it Shackleton defined courage and leadership.

Over the last year I've been lucky enough to watch the corporate equivalent at a major U.S. corporation – starting a new technology division bringing disruptive technology to market at General Electric.

One of GE's new divisions – GE's Energy Storage – has been given the charter to bring an entirely new battery technology to market. This battery works equally well whether it's below freezing or broiling hot. It's high density, long life, environmentally friendly and can go places other batteries can't.

This is a new division of a large, old company where one would think innovation had long been beaten out of them. You couldn't be more wrong. The Energy Storage division is acting like a startup, and Prescott Logan its General Manager, has lived up to the charter. He's as good as any startup CEO in Silicon Valley. Working with him, I've been impressed to watch his small team embrace Customer Development (and Business Model Generation) and search the world for the right product/market fit. They've tested their hypotheses with literally hundreds of customer interviews on every continent in the world. They've gained as good of an insight into customer needs and product feature set than any startup I've seen. And they've continuously iterated and gone through a few pivots of their business model. (Their current initial markets for their batteries include telecom, utilities, transportation and Uninterrupted Power Supply (UPS) markets.) And they've being doing this while driving product cost down and performance up.

GE's performance in implementing Customer Development gives lie to the tale that only web startups can be agile. Corporate elephants can dance.

So why this post?

GE's Energy Storage division is looking to hire two insanely great people who can act like senior execs in a startup:

A leader of Customer Development — think of it as a Product Manger running a product line who knows how to get out of the building and not write MRD's but listen to customers.

A Sales Closer – a salesman who can make up the sales process on the fly and bring in deals without a datasheet, price list or roadmap. They will build the sales team that follows.

If you've been intrigued by the notion of customer development in an early stage startup —getting out of the building to talk to customers and working with an engineering team that's capable of being agile and responsive – yet backed by a $150 billion corporation, this is the opportunity of a lifetime. (The good news/bad news is that you'll spend ½ your time on airplanes listening to customers.)

If you have 10 years of product management or sales experience, and think that you have extraordinary talent to match the opportunity, submit your resume by: 1) Clicking on Customer Development or Sales Closer, and 2) Emailing your resume to Prescott Logan at [email protected] Tell him you want to sign up for the adventure.

Honor and recognition in event of success.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Technology

February 22, 2011

A Visitors Guide to Silicon Valley

If you're a visiting dignitary whose country has a Gross National Product equal to or greater than the State of California, your visit to Silicon Valley consists of a lunch/dinner with some combination of the founders of Google, Facebook, Apple and Twitter and several brand name venture capitalists. If you have time, the President of Stanford will throw in a tour, and then you can drive by Intel or some Clean Tech firm for a photo op standing in front of an impressive looking piece of equipment.

The "official dignitary" tour of Silicon Valley is like taking the jungle cruise at Disneyland and saying you've been to Africa. Because you and your entourage don't know the difference between large innovative companies who once were startups (Google, Facebook, et al) and a real startup, you never really get to see what makes the valley tick.

If you didn't come in your own 747, here's a guide to what to see in the valley (which for the sake of this post, extends from Santa Clara to San Francisco.) This post offers things to see/do for two types of visitors: I'm just visiting and want a "tourist experience" (i.e. a drive by the Facebook / Google / Zynga / Apple building) or "I want to work in the valley" visitor who wants to understand what's going on inside those buildings.

I'm leaving out all the traditional stops that you can get from the guidebooks.

Hackers' Guide to Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is more of a state of mind than a physical location. It has no large monuments, magnificent buildings or ancient heritage. There are no tours of companies or venture capital firms. From Santa Clara to South San Francisco it's 45 miles of one bedroom community after another. Yet what's been occurring for the last 50 years within this tight cluster of suburban towns is nothing short of an "entrepreneurial explosion" on par with classic Athens, renaissance Florence or 1920's Paris.

California Dreaming

On your flight out, read Paul Graham's essays and Jessica Livingston's Founders at Work. Then watch the Secret History of Silicon Valley and learn what the natives don't know.

Palo Alto – The Beating Heart 1

Start your tour in Palo Alto. Stand on the corner of Emerson and Channing Street in front of the plaque where the triode vacuum tube was developed. Walk to 367 Addison Avenue, and take a look at the HP Garage. Extra credit if you can explain the significance of both of these spots and why the HP PR machine won the rewrite of Valley history.

Walk to downtown Palo Alto at lunchtime, and see the excited engineers ranting to one another on their way to lunch. Cram into Coupa Café full of startup founders going through team formation and fundraising discussions. (Noise and cramped quarters basically force you to listen in on conversations) or University Café or the Peninsula Creamery to see engineers working on a startup or have breakfast in Il Fornaio to see the VC's/Recruiters at work.

Stanford – The Brains

Drive down University Avenue into Stanford University as it turns into Palm Drive. Park on the circle and take a walking tour of the campus and then head to the science and engineering quad. Notice the names of the buildings; Gates, Allen, Moore, Varian, Hewlett, Packard, Clark, Plattner, Yang, Huang, etc. Extra points if you know who they all are and how they started their companies. You too can name a building after your IPO (and $30 million.) Walk by the Terman Engineering building to stand next to ground zero of technology entrepreneurship. See if you can find a class being taught by Tom Byers, Kathy Eisenhardt, Tina Seelig or one of the other entrepreneurship faculty in engineering.

Attend one of the free Entrepreneurial Thought Leader Lectures in the Engineering School. Check the Stanford Entrepreneurship Network calendar or the BASES calendar for free events. Stop by the Stanford Student Startup Lab and check out the events at the Computer Forum. If you have time, head to the back of campus and hike up to the Stanford Dish and thank the CIA for its funding.

Mountain View – The Beating Heart 2

Head to Mountain View and drive down Amphitheater Parkway behind Google, admiring all the buildings and realize that they were built by an extinct company, Silicon Graphics, once one of the hottest companies in the valley (Shelley's poem Ozymandias should be the ode to the cycle of creative destruction in the valley.) Next stop down the block is the Computer History Museum. Small but important, this museum is the real deal with almost every artifact of the computing and pre-computing age (make sure you check out their events calendar.) On leaving you're close enough to Moffett Field to take a Zeppelin ride over the valley. If it's a clear day and you have the money after a liquidity event, it's a mind-blowing trip.

Next to Moffett Field is Lockheed Missiles and Space, the center of the dark side of the Valley. Lockheed came to the valley in 1956 and grew from 0 to 20,000 engineers in four years. They built three generations of submarine launched ballistic missiles and spy satellites for the CIA, NSA and NRO on assembly lines in Sunnyvale and Palo Alto. They don't give tours.

While in Mountain View drive by the site of Shockley Semiconductor and realize that from this one failed company, founded the same year Lockheed set up shop, came every other chip company in Silicon Valley.

Lunch time on Castro Street in downtown Mountain View is another slice of startup Silicon Valley. Hang out at the Red Rock Café at night to watch the coders at work trying to stay caffeinated. If you're still into museums and semiconductors, drive down to Santa Clara and visit the Intel Museum.

Sand Hill Road – Adventure Capital

While we celebrate Silicon Valley as a center of technology innovation, that's only half of the story. Startups and innovation have exploded here because of the rise of venture capital. Think of VC's as the other equally crazy half of the startup ecosystem.

You can see VC's at work over breakfast at Bucks in Woodside, listen to them complain about deals over lunch at Village Pub or see them rattle their silverware at Madera. Or you can eat in the heart of old "VC central" in the Sundeck at 3000 Sand Hill Road. While you're there, walk around 3000 Sand Hill looking at all the names of the VC's on the building directories and be disappointed how incredibly boring the outside of these buildings look. (Some VC's have left the Sand Hill Road womb and have opened offices in downtown Palo Alto and San Francisco to be closer to the action.) For extra credit, stand outside one of the 3000 Sand Hill Road buildings wearing a sandwich-board saying "Will work for equity" and hand out copies of your executive summary and PowerPoint presentations.

Drive by the Palo Alto house where Facebook started (yes, just like the movie) and the house in Menlo Park that was Google's first home. Drive down to Cupertino and circle Apple's campus. No tours but they do have an Apple company store which doesn't sell computers but is the only Apple store that sells logo'd T-shirts and hats.

San Francisco – Startups with a Lifestyle

Drive an hour up to San Francisco and park next to South Park in the South of Market area. South of Market (SoMa) is the home address and the epicenter of Web 2.0 startups. If you're single, living in San Francisco and walking/biking to work to your startup definitely has some advantages/tradeoffs over the rest of the valley. Café Centro is South Park's version of Coupa Café. Or eat at the American Grilled Cheese Kitchen. (You're just a few blocks from the S.F. Giants ballpark. If it's baseball season take in a game in a beautiful stadium on the bay.) And four blocks north is Moscone Center, the main San Francisco convention center. Go to a trade show even if it's not in your industry.

The Valley is about the Interactions Not the Buildings

Like the great centers of innovation, Silicon Valley is about the people and their interactions. It's something you really can't get a feel of from inside your car or even walking down the street. You need to get inside of those building and deeper inside those conversations. Here's a few suggestions of how to do so.

If you want the ultimate startup experience, see if you can talk yourself into carrying someone's bags as they give a pitch to a VC. Be a fly on the wall and soak it in.

If you're trying to get a real feel of the culture, apply and interview for jobs in three Silicon Valley companies even if you don't want any of them. The interview will teach your more about Silicon Valley company culture and the valley than any tour.

Go to at least three tech-oriented Meetup s or Plancast events in the Valley or San Francisco (Meetup is a deep list. Search for "startup" meetup's in San Francisco, Palo Alto and Santa Clara.)

Check out the meetups from iOS Developers, Hackers and Founders, 106Miles and Ideakick. Catch a monthly hackathon. Subscribe to StartupDigest Silicon Valley edition before you visit.

Find a real 3-10 person startup, working from a small crammed co-working space and sit with them for an afternoon. Offer to code for free. San Francisco has many co-working spaces (shared offices for startups). They're great to get a feel of what it's like to start when there's just a few founders and you don't have your own garage.Visit Founders Den, Sandbox Suites, Citizenspace, pariSoma Innovation, the Hub, NextSpace, RocketSpace, and DogPatch Labs. Driving down the valley see Studio G in Redwood City, Hacker Dojo in Mountain View, the Plug & Play Tech Center in Sunnyvale, Semantic Seed in San Jose.

Get invited to an event at Blackbox.vc and the Sandbox Network. See if there's a Startup Weekend or SVASE event going on in the Bay Area.

If you're visiting to raise money or to get to know "angels" use AngelList to get connected to seed investors before you arrive.

Use your entrepreneurial skill and get yourself into a Y-Combinator dinner or demo day, a 500 Startups or Harrsion Metal event. Go to a Techcrunch event. And of course go to a Lean Startup Meetup.

Talk yourself into a job.

Never leave.

Filed under: Family/Career, Technology, Venture Capital

February 15, 2011

College and Business Will Never Be the Same

Education is what remains after one has forgotten everything he learned in school

Attributed to Albert Einstein, Mark Twain and B.F. Skinner

There are 4633 accredited, degree-granting colleges and universities in the United States. This weekend I had dinner last night with one of them – a friend who's now the President of Philadelphia University. He's working hard to reinvent the school into a model for 21st century Professional education.

The Silo Career Track

One of the problems in business today is that college graduates trained in a single professional discipline (i.e. design, engineering or business) end up graduating as domain experts but with little experience working across multiple disciplines.

In the business world of the of the 20th century it was assumed that upon graduation students would get jobs and focus the first years of their professional careers working on specific tasks related to their college degree specialty. It wasn't until the middle of their careers that they find themselves having to work across disciplines (engineers, working with designers and product managers and vice versa) to collaborate and manage multiple groups outside their trained expertise.

This type of education made sense in design, engineering and business professions when graduates could be assured that the businesses they were joining offered stable careers that gave them a decade to get cross discipline expertise.

20th Century Professional Education

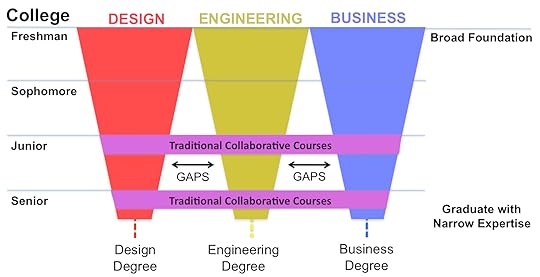

Today, college graduates with a traditional 20th century College and University curriculum start with a broad foundation but very quickly narrow into a set of specific electives focused on a narrow domain expertise.

Interdisciplinary and collaborative courses are offered as electives but don't really close the gaps between design, engineering and business.

Interdisciplinary Education in a Volatile, Complex, and Ambiguous World

The business world is now a different place. Graduating students today are entering a world with little certainty or security. Many will get jobs that did not exist when they started college. Many more will find their jobs obsolete or shipped overseas by the middle of their career.

This means that students need skills that allow them to be agile, resilient, and cross functional. They need to view their careers knowing that new fields may emerge and others might disappear. Today most college curriculum are simply unaligned with modern business needs.

Over a decade ago many research universities and colleges recognized this problem and embarked on interdisciplinary education to break down the traditional barriers between departments and specialties. (At Stanford, the D-School offers graduate students in engineering, medicine, business, humanities, and education an interdisciplinary way to learn design thinking and work together to solve big problems.) This isn't as easy as it sounds as some of the traditional disciplines date back centuries (with tenure, hierarchy and tradition just as old.)

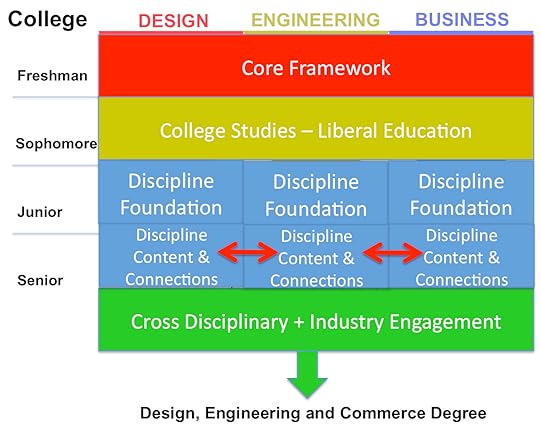

Philadelphia University Integrates Design, Engineering and Commerce

At dinner, I got to hear about how Philadelphia University was tackling this problem in undergraduate education. The University, with 2600 undergrads and 500 graduate students, started out in 1884 as the center of formal education for America's textile workers and managers. The 21st century version of the school just announced its new Composite Institute for industrial applications.

(Full disclosure, Philadelphia University's current president, Stephen Spinelli was one of my mentors in learning how to teach entrepreneurship. At Babson College he was chair of the entrepreneurship department and built the school into one of the most innovative entrepreneurial programs in the U.S.)

Philadelphia University's new degree program, Design, Engineering and Commerce (DEC) will roll out this Fall. It starts with a core set of classes that all students take together; systems thinking, user-centric design, business models and team dynamics. These classes start the students thinking early about customers, value, consumer insights, and then move to systems thinking with an emphasis on financial, social, and political sustainability. They also get a healthy dose of liberal arts education and then move on to foundation classes in their specific discipline. But soon after that Philadelphia University's students move into real world projects outside the university. The entire curriculum has heavy emphasis on experiential learning and interdisciplinary teams.

The intent of the DEC program is not just teaching students to collaborate, it also teaches them about agility and adaptation. While students graduate with skills that allow them to join a company already knowing how to coordinate with other functions, they carry with them the knowledge of how to adapt to new fields that emerge long after they graduate.

This type of curriculum integration is possible at Philadelphia because they have:

1) a diverse set of 18 majors, 2) three areas of focus; design, engineering, and business and 3) a manageable scale (~2,600 students.)

I think this school may be pioneering one of the new models of undergraduate professional education. One designed to educate students adept at multidisciplinary problem solving, innovation and agility.

College and business will never be the same.

Lessons Learned

Most colleges and Universities are still teaching in narrow silos

It's hard to reconfigure academic programs

It's necessary to reconfigure professional programs to match the workplace

Innovation needs to be applied to how we teach innovation

Filed under: Teaching, Technology

February 8, 2011

Startup America – Dead On Arrival

For its first few decades Silicon Valley was content flying under the radar of Washington politics. It wasn't until Fairchild and Intel were almost bankrupted by Japanese semiconductor manufacturers in the early 1980's that they formed Silicon Valley's first lobbying group. Microsoft did not open a Washington office until 1995.

Fast forward to today. The words "startup," "entrepreneur," and "innovation" are used fast, loose and furious by both parties in Washington. Last week the White House announced Startup America, a public/private initiative to accelerate accelerate high-growth entrepreneurship in the U.S. by expanding startups access to capital (with two $1 billion programs); creating a national network of entrepreneurship education, commercializing federally-funded research and development programs and getting rid of tax and paperwork barriers for startups.

What's not to like?

My observation. Startup America is a mashup of very smart programs by very smart people but not a strategy. It made for a great photo op, press announcement and impassioned speeches. (Heck, who wouldn't go to the White House if the President called.) It engaged the best and the brightest who all bring enormous energy and talent to offer the country. The technorati were effusive in their praise.

I hope it succeeds. But I predict despite all of Washingtons' good intentions, it's dead on arrival.

Dead On Arrival

I got a call from a recruiter looking for a CEO for the Startup America Partnership. Looking at the job spec reminded me what it would be like to lead the official rules committee for the Union of Anarchists.

There are three problems. First, an entrepreneurship initiative needs to be an integral part of both a coherent economic policy and a national innovation policy – one that creates jobs for Main Street versus Wall Street. It should address not only the creation of new jobs, but also the continued hemorrhaging of jobs and entire strategic industries offshore.

Second, trying to create Startup America without understanding and articulating the distinctions among the four types of entrepreneurship (described later) means we have no roadmap of where to place the bets on job growth, innovation, legislation and incentives.

Third, the notion of a public/private partnership without giving entrepreneurs a seat at the policy table inside the White House is like telling the passengers they can fly the plane from their seats. It has zero authority, budget or influence. It's the national cheerleader for startups.

The Four Types of Entrepreneurship

"Startup," "entrepreneur," and "innovation" now means everything to everyone. Which means in the end they mean nothing. There doesn't seem to be a coherent policy distinction between small business startups, scalable startups, corporations dealing with disruptive innovation and social entrepreneurs. The words "startup," "entrepreneur," and "innovation" mean different things in Silicon Valley, Main Street, Corporate America and Non Profits. Unless the people who actually make policy (rather than the great people who advise them) understand the difference, and can communicate them clearly, the chance of any of the Startup America policies having a substantive effect on innovation, jobs or the gross domestic product is low.

1. Small Business Entrepreneurship

Today, the overwhelming number of entrepreneurs and startups in the United States are still small businesses. There are 5.7 million small businesses in the U.S. They make up 99.7% of all companies and employ 50% of all non-governmental workers.

Small businesses are grocery stores, hairdressers, consultants, travel agents, internet commerce storefronts, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, etc. They are anyone who runs his/her own business. They hire local employees or family. Most are barely profitable. Their definition of success is to feed the family and make a profit, not to take over an industry or build a $100 million business. As they can't provide the scale to attract venture capital, they fund their businesses via friends/family or small business loans.

2. Scalable Startup Entrepreneurship

Unlike small businesses, scalable startups are what Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and their venture investors do. These entrepreneurs start a company knowing from day one that their vision could change the world. They attract investment from equally crazy financial investors – venture capitalists. They hire the best and the brightest. Their job is to search for a repeatable and scalable business model. When they find it, their focus on scale requires even more venture capital to fuel rapid expansion.

Scalable startups in innovation clusters (Silicon Valley, Shanghai, New York, Bangalore, Israel, etc.) make up a small percentage of entrepreneurs and startups but because of the outsize returns, attract almost all the risk capital (and press.) Startup America was focussed on this segment of startups.

3. Large Company Entrepreneurship

3. Large Company Entrepreneurship

Large companies have finite life cycles. Most grow through sustaining innovation, offering new products that are variants around their core products. Changes in customer tastes, new technologies, legislation, new competitors, etc. can create pressure for more disruptive innovation – requiring large companies to create entirely new products sold into new customers in new markets. Existing companies do this by either acquiring innovative companies or attempting to build a disruptive product inside. Ironically, large company size and culture make disruptive innovation extremely difficult to execute.

4. Social Entrepreneurship

4. Social Entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurs are innovators focus on creating products and services that solve social needs and problems. But unlike scalable startups their goal is to make the world a better place, not to take market share or to create to wealth for the founders. They may be nonprofit, for-profit, or hybrid.

So What?

Each of these four very different business segments require very different educational tools, economic incentives (tax breaks, paperwork/regulation reduction, incentives), etc. Yet as different as they are, understanding them together is what makes the difference between a jobs and innovation strategy and a disconnected set of tactics.

Go take a look at any of the government organizations talking about entrepreneurship and see how many of its leaders or staff actually started a company or a venture firm. Or had to make a payroll with no money in the bank. We're trying to kick-start a national initiative on startups, entrepreneurs and innovation with academics, economists and large company executives. Great for policy papers, but probably not optimal for making change.

Rather than having our best and the brightest visit for a day, what we need sitting in the White House (and on both sides of the aisle in Congress) are people who actually have started, built and grown companies and/or venture firms. (If we're serious about this stuff we should have some headcount equivalence to the influence bankers have.)

Next time the talent shows up for a Startup America initiative, they ought to be getting offices not sound bites.

Lessons Learned

Lots of credit in trying to "talk-the-talk" of startups

No evidence that Washington yet understands the types of entrepreneurs and startups; how they differ, and how they can form a cohesive and integrated jobs and innovation strategy

Not much will happen until entrepreneurs and VC's have a seat at the table

Filed under: Technology, Venture Capital

February 3, 2011

VC's Are Not Your Friends

One of the biggest mistakes entrepreneurs make is not understanding the relationship they have with their investors. At times they confuse VC's with their friends.

Lets Go to Lunch

At Rocket Science our video game company was struggling. Hubris, bad CEO decisions (mine) and a fundamental lack of understanding that we were in a "hits-based" entertainment business not in a Silicon Valley technology company were slowly killing us.

One day I got a call from my two investors, "Hey Steve, we're both going to be up in San Francisco, lets grab lunch." I liked my two investors. I'd known them for years, they were smart, trying to figure out the video game market with me, (in hindsight a business that none of us knew anything about and shouldn't have been in,) coached me when needed, etc. Our board meetings were collegial and often fun.

We were just about to have a board meeting in another week to talk about raising another round of financing to keep our struggling disaster afloat. I had assumed that my VC's were behind me. Thinking we were having a social call, I was completely unprepared for the discussion. (Lesson – never take a VC meeting without knowing the agenda.)

"Steve, we thought we'd tell you this before the board meeting, but both our firms are going to pass on leading your next round." I was speechless. I felt like I had just been kicked in the gut and stabbed in the back These were my lead investors. It was the ultimate vote of no confidence. If they passed the odds of anyone in the entire country funding us was zero.  I knew they had been questioning our ability to stay afloat as a company in the board meetings so this wasn't a complete surprise but I would have expected some offer a bridge loan or some sign of support. (I finally got them to agree if I could find someone else to lead the round they would put in a token amount to say they were still supportive.)

I knew they had been questioning our ability to stay afloat as a company in the board meetings so this wasn't a complete surprise but I would have expected some offer a bridge loan or some sign of support. (I finally got them to agree if I could find someone else to lead the round they would put in a token amount to say they were still supportive.)

"Is this about me as the CEO?" I asked. "I'll resign if you guys think you can hire someone else you want to back." They looked a bit sheepish and replied, "No it's not you. You should stay and run the company. However, we realized that we've backed a business we don't know much about, the company is a money sink and both our firms have no stomach for this industry."

"But I thought you guys were my friends?!" You're supposed to support me!! I said out of utter frustration.

VC's Are Not Your Friends

I had just gotten a very expensive reminder. I liked my board members. They liked me. But while I was just seeing a single board member, I was just one of twenty companies in their current fund portfolio. Their fiduciary responsibility was to manage a portfolio of investments for their limited partners. And what they promised their own investors was that they would invest money in deals that would grow in value and achieve liquidity. As much as they liked me as the entrepreneur, they couldn't throw good money after bad when they thought the deal went south.

I wish I could tell you I understood this all at the time. I didn't. I was angry, took it personally for a long time (past the demise of Rocket Science) until I realized they were right.

While the best VC's treat entrepreneurs like you are their most important customer, and they add tremendous value to your startup (recruiting, strategy, coaching, connections, etc.) they are not doing it out of the goodness of their hearts. Entrepreneurs need to understand that VC's are simply a sophisticated form of financial investors who in turn need to satisfy their own investors. At the end of the day VC's have to provide their limited partners with great returns or they aren't going to be able to raise another fund.

If you succeed so do they. Great VC's do everything they can to make you successful. But just like your bank, credit card company, mortgage holder, etc. they are not confused where their long term loyalty lies.

It's not with you.

Postscript

The irony is 15 years later, no longer doing startups, these two VC's truly have become my friends. We have lunch often, teach together and swap war stories of the day they pulled my funding.

It wasn't an easy lesson.

Lessons Learned

You see one VC, they see 20 CEO's

Don't confuse your business with your VC's business

Your interests are aligned if you both see the same path to liquidity

Don't confuse being friendly with your VC's with VC's as your friend

Filed under: Rocket Science Games, Venture Capital

January 31, 2011

Startups – So Easy a 12 Year Old Can Do It

Out of the mouths babes. Maybe because it's a company town and everyone in Silicon Valley has a family connection to entrepreneurship. Or maybe I just encountered the most entrepreneurial 12 year olds every assembled under one roof. Or maybe we're now teaching entrepreneurial thinking in middle schools. Either way I had an astounding evening as one of the judges at the Girls Middle School 7th grade Entrepreneurial night.

12 Year Olds Writing Business Plans

In this school every seventh-grade girl becomes part of a team of four or five that create and run their own business. The students write business plans, request start-up capital from investors, receive funding for their companies, make product samples, manufacture inventory, and sell their products to real-world customers. This class is experiential learning at its best.

It was amazing to read their plans talking about income, revenue, cost of goods, fixed and variable costs, profit and liquidity. (Heck, I don't think I understood cost of goods until I was 30.) As they built their business, having to work with a team meant the girls learned firsthand the importance of creativity, teamwork, communication, consensus-building, personal responsibility, and compromise. (Next time I have to adjudicate between founders in a real startup I can now say, "I've seen 12 year olds get along better than you.")

One highlight of the girls Entrepreneurial Program is the annual "Entrepreneurial Night" that showcases the newly created businesses for both the school and the wider Silicon Valley community. All of the teams had a booth where they sold their products as if in a trade show. Then after a break, each of the 12 teams of 7th graders got up in front of audience of several hundred (and the judges) and presented their Powerpoint summaries of their business and progress to date. (I couldn't write or deliver a pitch that good until my third startup.)

Wow.

(Watching these girls gave me even more confidence about predictions of the future of entrepreneurship in the post When It's Darkest, Men See the Stars.)

Women as Entrepreneurs

Teaching entrepreneurship in middle school is an amazing achievement. But teaching it to young women is even better. Not all these girls will choose to be career professionals in a corporate world. But learning entrepreneurial thinking early can help regardless of your career choice, be it teacher, mother, doctor, lawyer or startup founder. They will forever know that starting a company is not something that only boys do, but was something they mastered in middle school.

The Girls Middle School is not alone in teaching young students entrepreneurship. Organizations like Bizworld and The National Foundation for Teaching Entrepreneurship are also spreading the word. If you have any influence on the curriculum of your children's school, adding an entrepreneurship class will be good for them, good for your community and great for our country.

Lessons Learned

Middle school is a great time to introduce entrepreneurship into a curriculum

Students that age can master the basics of a small business

It's best taught as a full immersion, "get out of the building, make it, sell it and do it" experience

The lessons will last a lifetime

Extra credit if you teach it in a girls-only school

Filed under: Family/Career, Teaching

January 27, 2011

The 47th (-46) International Business Model Competition

Utah may be known for many things, but who would have thought that Utah, and particularly Brigham Young University (BYU), would be participating in the transformation of entrepreneurship?

I spent last weekend in Utah at BYU as a guest of Professor Nathan Furr, (a former Ph.D. student of our MS&E department at Stanford,) where they are set on being a leader in developing the management science of entrepreneurship. The most visible step was the first International Business Model Competition, hosted by the BYU Rollins Center for Entrepreneurship and Technology.

What's A Startup?

What's A Startup?

We've been teaching that the difference between a startup and an existing company is that existing companies execute business models, while startups search for a business model. (Or more accurately, startups are a temporary organization designed to search for a scalable and repeatable business model.) Therefore the very foundations of teaching entrepreneurship should start with how to search for a business model.

This startup search process is the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack. This solution stack proposes that entrepreneurs should first map their assumptions (their business model) and then test whether these hypotheses are accurate, outside in the field (customer development) and then use an iterative and incremental development methodology (agile development) to build the product. When founders discover their assumptions are wrong, as they inevitably will, the result isn't a crisis, it's a learning event called a pivot — and an opportunity to update the business model.

Business Model Versus Business Plan

The traditional business plan is an essential organizing and planning document to launch new products in existing companies with known customers and markets. But this same document is a bad fit when used in a startup, as the customers and market are unknown. A business plan in a startup becomes an exercise in creative writing with a series of guesses about a customer problem and the product solution. Most business plans are worse than useless in preparing an entrepreneur for the real world as "no business plan survives first contact with customers."

I suggested that if we wanted to hold competitions that actually emulated the real world (rather than what's easy to grade) entrepreneurship educators should hold competitions that emulate what entrepreneurs actually encounter – chaos, uncertainty and unknowns. A business model competition would emulate the "out of the building" experience of real entrepreneurs executing the customer development / business model / agile stack.

The 47th (-46) Annual Business Model Competition

From the seed of this initial idea last summer Professor Nathan Furr, and his team at BYU created a global business model competition, receiving over 60 submissions from across the world. Alexander Osterwalder, Professor Furr and I were the judges for selecting the winner from the final 4 contestants. The finals were held in the packed 800 seat BYU Varsity Theater with lines of students outside unable to get in. It was an eye-opener to see each of the teams take the stage to describe their journey in trying to validate each of the 9 parts of a business model, rather than the static theory of a business plan.

Each team used the business model canvas and customer development stack to go from initial hypotheses, getting outside the building to validate their ideas with customers, and going through multiple pivots to find a validated business model. The winner was Gamegnat, a gaming information portal (take a look at their presentation here.) At the end of the competition Gavin Christensen, managing director of Kickstart Seed Fund said, "This is going to change the way we invest." A nice testament to the visible difference in the quality of every teams presentation. The competition was an inspiration to the students, mentors and teaching teams.

Utah: Entrepreneurial Surprises

While I was in Utah, my host kept me busy with a series of talks. I spoke at lunch to a room of 400 entrepreneurs and investors from the region about the business model / customer development stack. I was quite surprised to find the depth and interest in innovation and sheer number of startups that I saw. I was even more surprised to learn that University of Utah has gone from being ranked 94th in the U.S. for startups created from university intellectual property to number one.

When I met with the faculty and Deans at BYU they were proud to tell me that they were number one in the U.S. for startups, licenses, and patent applications per research dollar. BYU has embraced an e-school approach, changing their curriculum to develop and teach the ideas in the business model / customer development stack. Their vision is to make the Business Model Competition an even larger international event, creating competitions at partner schools and providing the materials and insight to create a network of business model competitions culminating in an international finals event. And they are ready to share!

Keep your eye out for more details about creating your own competition, or contact Nathan Furr directly.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Teaching, Venture Capital

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 380 followers