Susan Orlean's Blog, page 10

March 29, 2011

Ranking Myself

The other day, I got a message on Twitter from my friend @glennf. "Goodreads outed you!" he wrote. "You gave your own books five stars!" It took me a moment to figure out what he meant. The night before, I had been noodling around on Goodreads, a social network for book lovers. Members create virtual bookshelves on the site, listing what they're reading and what they've read and awarding each book from one to five stars, depending on how well they liked it. The point is to connect you with other people who share your reading tastes and to facilitate, electronically, that most delicious of quick snoops—the scan of someone's bookshelves. The allure of social media and online community is such that Goodreads has really taken off, even though it is basically a bunch of lists.

I joined a few months ago and I love the idea of the site, but I haven't been very diligent about filling my bookshelves (right now, it looks like I've read a total of three books since mastering the alphabet; some users list more than a thousand). On a recent night when I was pretending that I don't really need any sleep, I decided it was a perfect time to visit Goodreads and add a few more books so my shelves didn't look quite so bare.

One of the other functions of Goodreads is that after analyzing the books you rank as your favorites, its hardworking algorithm gnome offers suggestions of other similar books you might like. That night, I discovered that the gnome had visited my page, and even though I had given only three books to work from, he had left the cheery message saying that I might like four or five nice books by a writer named Susan Orlean.

I had forgotten to add my own books to my "Already Read" list. By this time I was getting sleepy, so I decided to hold off on doing a major update to my bookshelves. But as the gnome had already listed my own books for me, all I had to do was click on them to add them to "Already Read." To play by the Goodreads rules, I also had to rank them. I hesitated for a minute. What were my options? Give myself three stars to show I was humble? Four stars, to split the difference? Five, just because, well, why not? This internal debate took place in a matter of seconds, and I settled on five stars for everything. Self-esteem! Anyway, I figured it was my own private ranking for my own page, and that the next time Goodreads decided to suggest books to me it would take into account that I'm interested in reading the kinds of books I'm interested in writing.

The operative word here is "private." Who was I kidding? Is anything on the Internet that doesn't leave a trail of gigantic, boulder-sized bread crumbs? The next day, Goodreads sent an e-mail to my friend Glenn—without realizing it, we were "following" each other on the site—announcing that Susan Orlean had rated some books, all by Susan Orlean—with five big stars each, and since we were Goodreads friends, he might want to take a look at my new super-favorite books. Glenn forwarded the e-mail to me. It made it look like I had suffered a disassociative personality break coupled with a narcissistic disorder. I suppose anyone else whom I'm linked with on Goodreads got the same announcement. After a few minutes of utter mortification, I realized the whole thing was more funny than embarrassing, but most of all it was a great reminder that the one thing you can always hear on the Internet is the sound of your own voice.

March 23, 2011

Doctor's Orders: Marijuana

These days, the punch line for every joke you hear in California seems to be "medical marijuana." You finish dinner at a restaurant, and your companion will ask, "Do you want dessert—or perhaps some medical marijuana?" I just spent two weeks near the beach in Venice, a town where the leading industries have always been tattoo parlors and T-shirt shops. Now, every other storefront is a doctor's office—walk-ins welcome. I called an old friend in Glendale and said I was in Venice. "Great!" he said. "I can come meet you for brunch—and pick up some medical marijuana!" Leaving aside those people undergoing chemotherapy or suffering from arthritis or the other miseries that marijuana relieves, the legal-if-you-have-a-prescription California pot law seems to be a source of endless merriment. Another friend told me that he had been golfing recently and, during a break, three of the men in his group—all of them middle-aged squares—pulled out of their pockets not cigars or hip flasks of Old Crow, but little vials containing tincture of marijuana. (After he told me this story, this same friend asked if I cared for some, because he happened to have a prescription for two different varieties—one to help you sleep, and one to help you not sleep.)

Part of what makes the whole thing so funny is the absolute ease with which anyone, for any reason, can get a prescription. You almost expect the doctors in their open-air beach offices to be wearing Mad Hatter costumes. The other laugh line is the fact that everyone calls it "medical marijuana." Since when did anyone besides Nancy Reagan call marijuana "marijuana," rather than "pot" or "weed"? It sounds so fusty and grandmotherly that it adds one more wink to the enterprise. Everyone seems to be in on the joke. On my last day in Venice, I even passed a ragged panhandler with a cardboard sign that said WILL WORK FOR MEDICAL MARIJUANA.

Photograph: Patrick Denker, Flickr CC.

March 21, 2011

Good Fortune

The day I visited the Twitter headquarters was an eventful one: someone had burned a piece of toast in the company lunchroom, setting off the fire alarm and an emergency evacuation. By the time I arrived, though, #toastfail was over, and it was back to business. To my great surprise, Twitter is not housed in a silver pod that orbits Earth at supersonic speeds, vacuuming up and then dispersing digital bits of worldwide chitchat; it's in a big, bland office building in downtown San Francisco, near a bowling alley and an Old Navy. Inside, the workspaces are open and everything is decorated with pretty bird stencils, and the whole place is buzzy and cheerful and full of sporty, fresh-faced people. If you didn't know any better, you might mistake it for something like, say, a staging area for a long bike race.

Twitter is growing like crazy—I've heard that half a million new users sign up every month—so the staff has grown like crazy, too. My lunch date, Del Harvey, who is the head of Trust and Security, joined when there were only twenty-five employees; now, just four years later, there are eight hundred. That's big enough that a Twitter employee might be following another Twitter employee on Twitter without realizing they both worked for the company. I'm not exactly sure what all those eight hundred people do. I'm always mystified by the day-to-day workings of entities like Twitter that provide framework but not content, but I suppose it could be compared to the U.S. Postal Service, which manages to keep a lot of people employed doing lots of stuff other than writing letters. Whatever they do seems to be working, which is probably as much as I need to know.

The other highlight of my trip to San Francisco was stumbling onto a fortune-cookie factory in Chinatown. I could never picture how the fortunes ended up inside the cookies, but now I know: the oldest, clankiest piece of machinery on earth spits out little cookie discs, and a worker grabs a disc, folds it over a metal spike, takes one slip of paper out of a pile of fortunes, tucks it into the folded cookie, and then folds the cookie again. In a minute, the cookie cools and hardens into shape, and, just like that, the little message in its tasty casing is sent out into the world. Another mystery solved.

Photograph: Wally Gobetz, via Flickr.

March 16, 2011

An Education

I teach a non-fiction writing class at New York University, and one of my great pleasures is deciding on the syllabus. This year, I decided to assign John Hersey's epic "Hiroshima." I knew it would be a surprise to my students. Even though it was so celebrated when it was first published, in 1946, as an article in this magazine and, later, as a book, "Hiroshima" seems to have slipped from notice. It's such a staggering work, reported so precisely and written so masterfully, that I was excited to introduce it to my students.

None of them had ever read it before, and the Japan it describes—isolated and insular, made up of quiet working-class people—would have been hard for them to picture. In their lifetimes, Japan has always been portrayed as a rich and invincible modern monolith, almost more of a corporation than a country. I doubt most of my students imagined it also including shopkeepers, farmers, artisans, and poor fishermen. It's not that these students aren't worldly and well read; it's that the image of an affluent, industrialized Japan has become so dominant that it has blotted out all the nuance of what that country really is like.

When a disaster strikes, we become acquainted, or reacquainted, with the part of the world that has been stricken. It's the only good thing you can say about such events—that they swivel the world's spotlight for a moment, and we get a quick education about a place we have put out of our minds or perhaps never knew at all—Banda Aceh, say, or Port-au-Prince. In the case of this horror in Japan, it is a reminder that Japan is not just Toyota salary men and post-modern punk kids in Shibu-ya. The tsunami washed over little villages and ordinary, work-a-day towns, the parts of Japan many of us didn't even know existed. Now it will be hard to ever forget them.

March 10, 2011

Airwaves

My father, who passed away three years ago, had a few signature phrases. If someone passed us on the freeway, he would laugh and call out, "Good luck! You don't want to be late for your funeral!" Whenever we talked about my future and I insisted that I wanted to be a writer and not a lawyer, he would reply, "Going to law school never hurt anyone." If he happened to turn on the local NPR station in the middle of a fund drive—what seemed like a frequent occurrence—he would sigh with disapproval and say, "Shameful! What are they—beggars?"

I wonder what he would have thought of the current pickle NPR is in, some of which is the unsurprising and unenviable result of being a dependent independent—a beggar. I'm afraid he wouldn't be surprised. In a perfect world, some wonderful benefactor would fund NPR and expect nothing for the favor. When, in the history of human civilization, has this ever happened? And yet how can an organization like NPR do what it does without lots of money, gathered by begging listeners, government, and sponsors?

Well, would it be so terrible if NPR had ads? The one redeeming fact about advertising is nothing is hidden. I am a mattress store; I buy time to plug my store on your station, period. It's the ultimate transparency; a list of a station's advertisers reveals everything you need to know. With NPR, it's complicated. Selling an ad to a mattress store seems easier, and less compromising, in many ways, than having to romance a government grant or a corporate sponsor. The problem is I don't want to listen to a mattress-store jingle. I rarely listen to commercial radio, and when I do, I'm shocked by how many ads there are, and how annoying they are, and how bad the radio station usually is. I can't flip back to NPR fast enough.

Another one of my father's favorite phrases was "Nothing that can be fixed with money is worth crying over." In the case of NPR, he was right; he just never explained where to find the money to fix it.

March 3, 2011

The Wanderer

At the risk of sliding into the deep, deep hole that is cat obsession, I have to tell you the next chapter in the continuing story of Mittens, the stray who showed up at our house a few months ago.

For some time, we ignored the cat, who popped up one day, and then lurked around the backyard, skulking like a juvenile delinquent, except when she was engaged in a yowling standoff with Gary, our bossy alpha cat. After a few weeks of this, Mittens—as my son christened her—inched her way to the back door. Even though I got the usual warnings of how this would mean we would never be rid of her, I started feeding her, and made a comfortable spot on the back step for her to snooze. When winter came and Mittens was still hanging around, I let her in. I found it impossible to look at her through a veil of snowflakes without a surge of guilt and concern. As I expected, Mittens upset the finely calibrated animal dynamics in my household, but I felt it was the right thing to do.

All the while, I looked for Lost Cat posters featuring Mittens's piercing stare and fluffy black face. Nothing.

Mittens settled in, the way an unemployed cousin who visits without a fixed departure date settles in—there but not quite there, until the day you notice Cousin has hung his clothes in the closet and started receiving mail. Mittens had become a sort of resident alien, whether we wanted it or not. I finally decided that if she was going to be taking up residence, however temporary, I ought take her to the vet, to check her out. I also had a private worry that she might be a pregnant adolescent—her belly was so round, and she slept all the time. While at the vet, I'd have her scanned to see if she had an identification microchip. I thought it very unlikely; she had been pretty moth-eaten when she showed up, making me think she was a barn cat, half wild, and not the sort of pampered pet who someone worried over enough to go to that sort of trouble.

The vet was full of surprises.

"Your cat is a boy," she said.

"Not pregnant, I guess," I replied, brightly.

"No."

"How old is, umm, he? A year? Maybe two?" I asked.

"Ten," the vet said. "At least."

Mittens—Is that name too emasculating? I suddenly wondered—was whisked away to be weighed, and scanned for the microchip.

"He has a chip," the vet said, dropping my merely overweight elderly male cat on the exam table. The address on the chip was fifty miles from us. Mittens, the sleepiest, laziest cat on the planet, had hiked fifty miles to my doorstep? It was baffling. I didn't think I could bear any further surprises, so we headed home.

That evening, I called the number listed on the microchip. In my agitated state, I first misdialed and reached a woman in western New York who sounded very sorry that Mittens wasn't her cat, and said she would drive the two hundred miles to get him if he needed a new home. "My husband is allergic," she added, "but maybe he could learn to live with it."

I thanked her and dialed again, this time correctly. Another woman answered and listened as I explained how I'd gotten her phone number off the cat's subcutaneous chip. "Wow," she said, "you have Gomez? My god, how is Gomey?"

"He's fine," I said. "He's at my house. I can't believe he walked all this way." It turned out that he hadn't. The woman said that she had adopted him from a shelter three or four years ago and had kept him for a short while, but he peed everywhere and didn't get along with her other cat so she ended up taking him back. A friend of hers then went to the shelter and fished Gomez back out; for some reason she couldn't keep him, so gave him to someone else who lived not far from me.

I worried that I was losing the thread. "Who does he belong to?" I asked. Hard to say, she explained; she said she would call her friend.

The next morning my phone rang before breakfast.

"What are you doing to Gomez?" a raspy-voiced woman shouted at me, as soon as I said hello. "Why are you dumping him?"

"What are you talking about?" I shouted back. "I'm not dumping him! I've been taking good care of this cat for months! I'm just trying to figure out if he has another home!"

For a moment, she was quiet, and then said, "Well, I was so ticked off at Mary for dumping him back at the shelter that I had to go back and get him. I can't have any more cats! I have dozens of cats!"

"I see," I said, even though I wasn't sure I did.

"So I got Gomey, and I found a gal who's sort of … sort of a cat person, she has a million of them, and dogs, and maybe even pigs, and I gave her a nice amount of money and took Gomez to her, but I think she stuck him in her basement and just threw food down there once in a while."

"Maybe that's why he ran away," I said.

"I wouldn't call her if I were you. She got a nice amount of money to take care of him but she threw him in the basement." She took a cigarette break, and then resumed the excoriation of her friend, the one who had originally adopted Mittens and then returned him.

"Are you going to keep him?" she finally asked. I told her that I had grown to really love the cat; he was the most affectionate of all my many animals, perhaps because he was the most grateful, and his advanced age made me feel especially tender towards him. He had been bounced around so much that I hated the thought of bouncing him again—and we hadn't even explored the six years of his life that had led up to his being in the first shelter.

When I had spoken to the microchip woman I had given her my address, because she said she had the cat's vet records. Even though she had taken him in and then put him back out, she had been a conscientious owner, or so it seemed; she had gotten him microchipped and had spent over two hundred dollars having him examined and wormed and vaccinated.

The next day, I got her letter, with Mittens's information. According to the vet records, the day the letter arrived was his eleventh birthday.

February 25, 2011

Pedlar Lady

I have watched three minutes of "A Bug's Life" dozens and dozens of times, because it is the movie my husband likes to use to demonstrate the awesomeness of our high-definition TV. "Look at the details on those antennae!" he'd exclaim. "The ants almost look 3-D!"

I find myself similarly enthusiastic—missionary, almost—when it comes to e-books on my iPad. I sound like a commercial for Bass-o-Matic or Ginsu knives. "You can make the font huge!! It keeps track of where you stopped reading!"

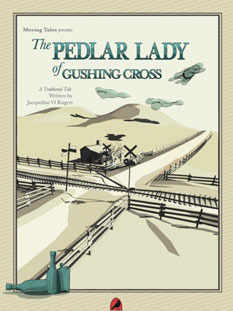

I used to use the iPad version of "Alice in Wonderland" as the demo in the second part of my e-book/iPad pitch. The electronic Alice, which is built around the original John Tenniel illustrations, is slightly and cleverly animated; Alice really does grow big and then small, and a bottle of pills will spill if you tap the screen. It's a blast. But the other day I bought a new book, "The Pedlar Lady of Gushing Cross," that is even more amazing; I'm so excited by it that I found myself pitching it to my mother, who wouldn't know a computer from a hacksaw. The story, by Jacqueline Rogers, is an adaptation of a folk tale about a poor old lady and her strange and wondrous dream. The writing is beautiful, and would make a fine book on paper. But what makes it so compelling is the way it lives on the screen. The illustrations look like pen-and-ink drawings, each page washed with a single tone, and they move in a subtle, dreamy way—the old lady rocks in her chair, a bell tolls, a crow circles.

There is a soundtrack in a few spots, nothing intrusive, but just enough to add one more dimension of surprise. It's not just a book, not quite a movie, not a video, not an interactive game: it's something new and thrilling. It is exactly why I think of electronic books as a chance to dilate the experience of reading, of storytelling, rather than something that threatens to take it away.

February 22, 2011

@leapofFaith

Sometimes, the Internet can feel like a middle-school playground populated by brats in ski masks who name-call and taunt with the fake bravery of the anonymous. But sometimes—thank goodness—it's nicer than real life.

Case in point: recently, I complained on Twitter about my new netbook, which was acting up. In response, I got lots of commiseration, advice, and curiosity (people on Twitter have a bottomless appetite for talking about techno-gadgetry). One response went a step further. "Sorry about your netbook," the person wrote, "and I'd be happy to try to fix it if you'd like."

I say "person" because I knew no details about this individual. On Twitter, you have a username of your devising, and each user has a short biography, which in many cases consists entirely of something useful and revealing like "I like gum" or "Big for my age." Let's call this user who offered to help me @MrMoustache. We exchanged a few messages; he explained that he was a male person living in Washington, D.C., with a background in computers. He had just been laid off and had a lot of time on his hands, and would be happy to take a look at my balky machine. Why? Just because, he explained, he enjoyed tinkering and, well, why not?

I can't really explain why @MrMoustache sounded trustworthy, but he did, and so I deleted my passwords, packed up the computer, and mailed it to him. The minute I left the post office I felt like I had a large hole in my head. I just mailed my computer to a stranger! I felt like an idiot—like I had fallen for one of those Times Square scams where a weeping teen-ager tells you he's been locked out of his grandmother's apartment and if you could loan him fifty dollars he could get a locksmith to let him in. At the same time, I had convinced myself that it would have made no sense for @MrMoustache to be a crook. What insane patience would be required to troll Twitter all day long waiting for someone to complain about her netbook and expect that she'd agree to mail it to you for repair? And yet—I just mailed my computer to a stranger! And yet, he seemed really nice. He seemed like a guy who just figured he could be helpful. Was I a sucker, or was I tapping into a spirit of community and generosity? Or, to put it more succinctly, would I ever get my computer back?

I did. After a few days, I got a package from @MrMoustache (whose real name and address I of course knew by then, since the U.S. Postal Service doesn't accept mail addressed to "@MrMoustache c/o Twitter Account"). It contained my computer and a note, saying he had removed some viruses and malware and did something to pep up the hard drive. He hoped that it would work better from now on, and he signed off saying that he'd see me online.

I'm not sure I'd ever do something like this again, and whenever I tell the story of my Twitter computer repair I marvel at the crazy trust it took—and frankly, my luck that @MrMoustache was a good guy and not a crook. But I'd prefer to think it also means something bigger and better than that.

Photograph: gillyberlin, Flickr CC.

February 18, 2011

Bookmarked

I feel somewhat responsible for the Borders Books bankruptcy. I went to college in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Borders was founded; at the time, there was one single Borders store, a dark, sprawling space on State Street right near campus, with the nooks and crannies and shadowy corners of a magical grotto. I spent many afternoons in the store, surrounded by books I'd hauled down from the shelves, reading and whiling away the day. I bought a few of the books, but not many. If you plotted the dollars I spent at the cash register against the time I spent reading books there for free, Borders probably made less than a penny an hour off of me. I was living proof of a doomed business model.

There was a time when a line was drawn between independent bookstores and big chains—if you cue up your copy of "You've Got Mail" you need no further reminder of how the big chains were seen as malevolent and anti-book, full of zombified sales clerks and remaindered copies of "Battle Vehicles of World War II." I never saw it quite so simply, so I always tried to avoid those frequent book-people conversations that required me to declare that big bookstore chains were one baby step from plunging us into a scene from "Fahrenheit 451," their selling floors illuminated by the piles of smoldering paperbacks. Really? I wasn't so sure. When "The Orchid Thief" came out—not a book that immediately shouted "mainstream"—the independent bookstores, thank goodness, lined up to help me, but so did Barnes and Noble, and, even more, so did Borders. I know that big bookstores, with their discounts and cheap coffee, have made life miserable for independents, but I'm uncomfortable with demonizing any institution that is willing to present, for public consumption, written material.

The reaction to Borders' recent Chapter 11 filing has been interesting. Despite Borders being the enemy, it seems that no one, least of all independent booksellers, seems happy about it. Maybe if this had happened during those years when big bookstores were rolling over every small store it would have felt like victory for the small stores, but the scary times in the publishing business have made for a lot of battlefield buddies, and all booksellers now seem to see themselves as being on the same side. Borders had lousy management and made bad corporate decisions, so its fate is less like a terrible accident than a slow-motion slide into a ditch, but it's hard to be happy about a bookseller's demise. And now I feel guilty about all those hours I spent reading book after book for free.

February 11, 2011

Newsprint

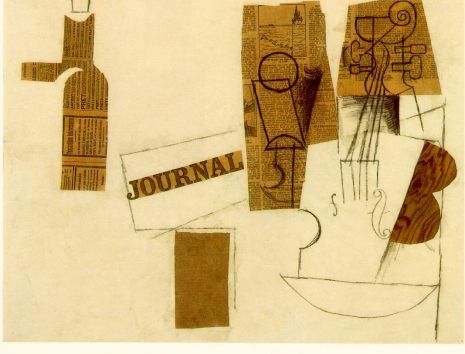

I went to see the new Picasso exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art yesterday. It's a fabulous collection of the artist's assemblages that riff on the shape and familiar essence of the folk guitar. Many of the pieces include a scrap or two of newspaper. At the time these were made—1912 or so—newspapers were both essential and ephemeral; they were cheap but priceless in their significance as the most important way people learned about the world. Dada art critics marveled at Picasso's genius; by incorporating such an ordinary, disposable item in his work, he was giving it the jolt of reality, playing against the preciousness of art with the common and perishable quality of scraps of Le Journal.

As I went through the exhibition, I found myself wondering if a piece of newspaper still has that meaning today, and, if it doesn't, what has taken its place. What material item has that same symbolism, so instantly recognizable and so loaded with associations? A printout of a Web page? A SIM card? Those may represent some of what a newspaper used to be, but not all of it: you don't wrap fish in them, or line a birdcage, or frame an important mention to hang behind the cash register. You don't have the cinematic shorthand of the lonely street empty except for a few broadsheet pages cartwheeling in a dusty breeze. The Web page may deliver the news, but it doesn't have the peculiar resonance of a material thing that huge numbers of people handle every day. And we would never have had a piece like "Siphon, Glass, Newspaper, and Violin." Maybe "Siphon, Glass, Smartphone, and Violin"?