Susan Orlean's Blog, page 7

October 17, 2011

Remembering Sue Mengers

Interviewing Sue Mengers was one of the saddest experiences of my professional life. Mengers, who died this weekend and will forever be known as a Hollywood super-agent, was at loose ends when we met. Her agenting career was over; she had lost all her clients and all her Hollywood access. She seemed fractured and lost as an outsider in the movie business, after so many years of being deeply inside. Being a big-deal movie agent seems to have one career trajectory: to be a no-longer-a-big-deal movie agent with a lot of time on your hands. She didn't wear it well.

The thing I admired about her was she didn't pretend to like it; she made no artful declarations about how it allowed her to spend more time with her family (she didn't have much family—just a husband who lived far away, and no children, which she explained had been a conscious choice so that she would have more time available for her movie-star clients). She didn't say she was delighted to have the time to write a book, although she did think about writing one as a source of income, which she clearly needed. She was frank. She had given her life to accomplish one thing: to get close to movie stars, and when they no longer enjoyed having her in their proximity, she had nothing left. She reminded me of those kinds of clumsy, bumbling kids who worship athletes but have no athletic talent, so they become the equipment manager for the high-school baseball team. The yearning to be near the thing that they can never be is like an open wound, always tender to the touch, and always with the potential to be too much in need, and therefore unpleasant, to those gorgeous people for whom so much comes easily. I felt Mengers's yearning so powerfully that it rattled me, and her bluntness about how much she wanted to be inside the glamour of Hollywood and how she felt when she achieved it—and how she felt when she was ejected from it—was hard to hear. It was as if she were summing up every emotion I'd ever had about wanting to be included.

Over the years I often wondered how she was doing, how she was making a living, whether she had gotten over feeling betrayed by the stars she had taken care of, who had then pushed her away. Mostly I wondered whether she ever felt she had done something with her life that had made her happy. I hope so. May she rest in peace.

Photograph of Mengers, with Faye Dunaway and Robert Evans in 1975, by Frank Edwards/Fotos International/Getty Images.

October 3, 2011

The Social Animal

Having animals in the city is entirely different from having animals out in the country. For one thing, it's more social. When you live on lots of acres without neighbors within a stone's throw, your dog-walks are usually solitary rambles over hill and dale. Your dog could go for years without ever encountering another dog. Cities, on the other hand, are Dog Central. In spite of the fact that our move from the Hudson Valley to Los Angeles has meant reducing our acreage by a factor of a zillion, my dog Ivy thinks she has died and gone to heaven. It's not that she likes the view or our adjacency to a dazzling array of manicure and bikini-wax outposts; it's the Laurel Canyon dog park, full of more canine odors and new friends than she would have met her whole life in the country.

I spent many years as a dog owner in Manhattan so I have my dog park etiquette hard-wired. As I recall, the rules are:

1. Ask the dog's name, never the owner's name.

2. For some reason, every single request for the name of the dog is immediately followed by an inquiry about the age of the dog. I have no idea why, but believe me, this is true.

3. Compliment every dog on its beauty. If the dog is one-eyed, three-legged, gap-toothed, and mangy, make your compliment more fulsome. Having trouble thinking of a way to effuse about a pug-ugly mutt? Just remember, no one ever tires of hearing how "great" a face their dog has. Remember: "great" sounds really good without having a specific definition.

4. Being deeply engaged in a cell-phone conversation while your dog is humping another dog, gnawing off someone's leg, or terrorizing a puppy is generally considered "anti-social" and "not cool."

5. Dog parks are more cliquish than any other human gathering with the possible exception of seventh grade. Deal with it.

6. In an interesting inversion of status, the reigning breed in the dog park these days is the really-oddball-unidentifiable-mixed-breed-mutt-found-wandering-the-street or its equivalent. The stranger the mutt the better; the more peculiar the circumstance of it coming into your life, the better. If you have a purebred dog, it better be a rescue, or you're going to be sneered at as an unbearable snob with questionable morals. (I say this as an observation about an encouraging social trend, not a criticism, by any means.)

7. You may never learn the names of any of the people you talk to in a dog park, even after many, many hours spent there with them, and many hours of conversation. But if—knock on wood—anything should ever happen to your dog, these nameless non-strangers will rally, sympathize, offer to help, and hold your hand. I know this from experience. That's why I'm kind of thrilled to be back in dog-park culture, even though I miss my acreage.

Photograph by holga_new_orleans, Flickr CC.

August 30, 2011

Moveable Feast

I moved a lot in my post-college years, and the single biggest, heaviest, most exasperating thing to move besides my books was my record collection. I had at least ten or fifteen crates of LPs, and then, in later years, a bunch of cassettes, too, and most of my moving involved figuring out how to get them from Apartment A to Apartment B (followed immediately by figuring out how and where to shelve them in Apartment B). The advent of CDs downsized my load considerably, but I still had a lot of plastic to cart around and store. Now my entire music collection is on one iPod. While the movers who probably sent their children to college thanks to me are probably very bitter about it, I am thrilled that I can pack all of my music for my upcoming yearlong relocation to Los Angeles in my pocket. Someday that same may be true for my books; instead of lugging box after box of them I will simply put my Kindle and my iPad into my purse and be done with it.

I love having the things I care about in reach at all times, but like all of the magical advances of technology, there is definitely something lost. In the past, when I was away from home for anything less than a permanent move, I carried along two or three books. As for music, when it was on vinyl, I never took it along with me; when it was on cassette, I took a handful; when my music collection was on CDs, I carried one of those disc wallets that could hold twenty or so. Basically, I was stuck with what I might find wherever I was going. My two or three books would tide me over and if they didn't, I would read the local paper or stop in a bookstore and see what they had. As for music, once I ran out of my stuff, I listened to the radio wherever I was. This made me insane sometimes: I was once stuck for five hours in a snowstorm on a Pennsylvania highway, and I hadn't brought any CDs with me on the trip. The only thing to listen to was the car radio, and the only station I could get was Christian talk radio. I made do—and probably ended up with a broader knowledge of evangelical Christianity than I had before the snowstorm.

I absolutely love portability, but it means that wherever you go, there you are. No matter how different the environment, you still have your Mumford & Sons albums and your entire archive of magazines and books. You have no real need to venture out, to take in what's at hand. You can stay in your own world, with a soundtrack of your own making, with distractions that you chose and will offer no surprise. Once something becomes easy and convenient, there's no going back: I certainly wouldn't trade being able to carry all my favorite music in my pocket for those fifteen heavy crates of LPs. But I have to admit that I still sometimes miss that jolt of the unfamiliar and even the uncomfortable that comes with being somewhere new.

Photograph by Orin Zebest, Flickr CC.

August 28, 2011

Wet Feathers

The word "bedraggled" was invented, I'm sure, for chickens and turkeys and guinea fowl in a tropical storm. It's not just the soggy feathers; it's a certain look of consummate, abject wetness poultry can convey. I had worried about how my birds would handle the hurricane, and checked on them this morning as the rain started. Most of the chickens were inside their coop, snuggled up. To my surprise, the ducks were inside, too—I thought ducks like water! What's up with that?—and my female duck was so nonchalant about the whole thing that she even laid an egg while the storm moved in.

The guinea fowl were outside, drenched and pathetic, but apparently fine—they were running around in their usual state of hysteria, which I took as a sign of their wellbeing. My bigger concern was for my turkeys. They're too big to fit in the chicken coop, so last year, I bartered with a neighbor for her huge, castoff dog house. (My side of the barter was agreeing to take care of her ducks over the winter, but they settled in so nicely that my neighbor decided to leave them with me, so I ended up with both the doghouse and the ducks.) I went to a great deal of trouble to flatten a spot for the house, put down drainage gravel, and set up the house—only to discover that the turkeys had no interest in it. As far as I know, they have never set foot inside. Even on the bitterest nights this winter, they slept out on their roost. I kept telling myself that turkeys wouldn't have survived as a species for billions of years if they didn't know how to take care of themselves, but still…what if they thought the house was actually for a dog and not for them? I've heard the story—rural legend, in my opinion—that turkeys will die in a rainstorm because they stand outside, looking up at the rain, and end up drowning. I would hate that.

At last check, my four turkeys were still out in the rain, not looking up into the rain like idiots, but simply waiting out the storm with a Patton-like stoicism, their usual somber dignity a little soaked and muddy, but intact. I'm in awe.

August 23, 2011

The Animals' War

My interest in seeing the play "War Horse" was almost, as they say in the philosophy of causation, over-determined. In case you haven't noticed, I like animals; you probably don't know that I am slightly obsessed with the First World War; and ever since researching my book on Rin Tin Tin (excerpted in this week's issue), I've been fascinated by the role animals played in that war. All three of those conditions predisposed me to being interested in "War Horse." The play is the story of a spirited colt named Joey and a boy, Albert, who tames him and falls in love with him and looks to him for inspiration, rather than turning to his drunken, reckless, vain father. When the war breaks out, the army goes shopping for horses, and Albert's father sells Joey, breaking his kid's heart. Albert then runs away from home and joins the army, mostly in hope of being reunited with his horse and bringing him back home from the battlefront.

There is much to love in the spectacle of the play. The horse puppets are astonishing and the production is almost like a dance performance, with so many moving pieces and ingenious design. (I hate to say this, but one of the coolest things was seeing a cavalry officer shot off his horse by artillery.) The narrative seemed almost incidental to the visual experience, and some of the scenes were wholly ridiculous (the friendly interaction between a British and German soldier in No Man's Land), but I am so glad I went to see it, and so glad it's been such a success. I like the fact that it reminds us that in the past, animals were in service in a greater variety of ways than they are typically today. These days, most of us, most of the time, interact with animals as either food or pets. At that time, though, animals were partners in work, and also, quite naturally, in war. An estimated sixteen million horses, dogs, oxen, camels, donkeys, mules and pigeons took part in the First World War. I won't give away the ending of the play, but most of those animals never came home from the war; they either died in battle or were left behind.

Everyone warned me that "War Horse" was going to make me cry, and I was so worried about it that I stuffed tissues in my pockets and practiced some deep breathing so I wouldn't embarrass myself (I tend to cry at the drop of a hat). There are plenty of human casualties in the play, but what you cry for most is the animals, because the people are so flawed—so foolish, so petty, or so naïve. The animals, in the middle of this manmade catastrophe of war, seem that much more innocent and willing and loyal, and ultimately doomed.

Photograph by Paul Kolnik.

August 17, 2011

Caution: Goats at Work

The other day, the New York Times reported that the city of Los Angeles is using a herd of South African boer goats to mow down the weeds on some hard-to-access city property. Because of my impending move to Los Angeles, I was very excited to hear about this: I like the idea of living in a city that uses goats as municipal workers. Apparently, I'm not the only one excited about this. It seems that the lawn-mowing goats have become quite an attraction. Animals just have that effect on people, making even mundane things seem enchanting. When was the last time you heard of lawn-mowing drawing a crowd? I'm not absolutely sure of the scope of a goat's skill set, but it's nice to think they might be promoted to other jobs, too. If they could somehow be trained to write parking tickets or be process servers or repo men, they might manage to make those professions less despised.

I'm all for putting animals to work, although my own experience with hiring them has been mixed. My guinea fowl were purchased to eat the ticks on our property, but since I've had Lyme disease three times in the past three years, I would say their effectiveness has been sub-par. The cats were acquired to deal with the mice in the basement, but they don't like being in the basement because, well, I don't know why. Maybe because there are mice down there. We have acres of poison ivy, which goats apparently love to eat, and I was on the very brink of buying a little brown buck named Pepper and assigning him to poison-ivy duty when I was warned that he was big on biting people on the rear end. Analyzing the cost-benefit ratio—eradication of poisonous plants versus integrity of my rear end—I went with the rear end. Even my slacker animals, though, do perform some yeoman labor: they are either pretty or funny or engaging, more than earning their keep by being interesting to be around.

August 5, 2011

The Moving Menagerie

In a matter of weeks, my husband and I will pack up everything but our winter clothes and park ourselves in Los Angeles until next spring. My husband has business there; I am merely a camp follower. It is a sign of some special and strange quality of my life that the first question people ask when hearing this news isn't, "How do you feel about moving to L.A.?" or "How will your son like living there?" but, "Oh my god, what about the chickens?" This is a problem of my own making, so I accept it. The fact is the question of what will become of my various animals is probably the subject most on my mind these days.

Some of those questions are easily answered. The cattle, for instance, will stay in New York, with our house-sitters. (But really, wouldn't it be totally awesome to have twelve Black Angus in a Los Angeles backyard?) The ducks and turkeys and guinea fowl, who need more space than we have in California, will stay, although I sure would like to bring them. (What an icebreaker at neighborhood get-togethers!) The dog, of course, will come with us. Funny how moments like this draw the line between animals that are more connected to the landscape (cattle, for instance) than to the humans who own them, versus those animals (dogs) that are extended family members. You would no sooner leave a dog behind with a caretaker than you would leave one of your kids. The cats and the chickens, though, do sort of straddle that line.

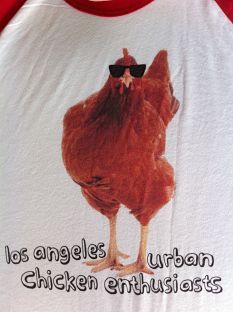

Re: chickens. It is legal to have them in Los Angeles, as long as they're a polite distance from your neighbors; and there's a lively L.A. chicken scene already in place (I already have my Los Angeles Urban Chicken Enthusiasts T-shirt, courtesy of one of the members.) But our backyard in California is small. Moreover, there are zillions of coyotes and bobcats hanging out in the neighborhood, and they are not the scrawny East Coast models: like everyone in Los Angeles, the coyotes I've seen there look like they work out a lot with personal trainers. The idea of putting a coyote magnet in the backyard, someplace where the coyotes can bench-press four hundred pounds, is terrifying. At least for the moment, the chickens will stay here.

And what about the cats? Even though I still don't understand cats—to me, they're like foreign-exchange students here for the semester—we now have three of them, and I'm very attached to them. There's Gary, a little female barn cat who we adopted when she was tiny; Leo, a tawny-colored male who we got from a local shelter; and Mittens, the stray I've written about here, who is now fully vested as a family member. The three of them are used to coming in and out as they please, which in Los Angeles means they would be a snack-size serving for a coyote in no time. (Isn't it weird that moving from rural upstate New York to the center of the nation's second-largest city means having MORE predator issues rather than fewer?). Cats in Los Angeles, in other words, are either indoor cats or they're goners. Can we convince these cats that being outside these past few years was a big mistake? How will they react to that? Late at night, I picture us in our small house in Los Angeles with the three cats hurling themselves against the windows, yowling. This is when I take a sleep aid. We have talked about taking just one of the cats—maybe whichever seems the most adaptable to indoor life. That would be Mittens, because he's old and lazy. On the other hand, Leo has a heart problem, so maybe we should take him instead, to be sure he's being doted on. But that would leave Gary and Mittens here in New York together, and they hate each other. We could take—oh, never mind. This is the sort of thing that I suspect we will decide in the very last minute, because if you love animals and have to leave them, even for a little while, there's no simple way to figure it out.

Photograph by Susan Orlean.

August 1, 2011

Jukebox

I'm very excited about my new Spotify account, which gives me access to twenty gazillion songs any time, all the time. The day I opened my account, though, I sat there perplexed. How would I figure out what I wanted to hear? The music I already know and like, I already own; the music I don't know, I don't know. I stared at the Spotify Web site for about ten minutes and then logged out and walked away. That night, I thought wistfully about listening to the radio, which I did just about constantly when I was growing up. There was a great radio station in Cleveland—WMMS—and it played album sides and new rock bands and bootlegged concert tapes; it was the soundtrack of my entire childhood and teen-age years. What was un-Spotifyish about it was that there were DJs in charge, muttering to us in their slightly stoned, intimate way, urging us to listen to new music and bands, talking about the concerts they'd seen; serving, essentially, as an older sibling who was turning me on to cool new grown-up music. Those DJs changed my life: they pushed my taste in unexpected directions and personalized music, making it make sense in a context.

I love the Internet, and I am definitely going to figure out how to manage now having what is essentially the biggest jukebox in the universe and a lifetime supply of quarters. But like so much on the Web, the one thing that is hard to replace is that intimate voice. I don't mean having ten thousand "like" buttons clicked on a band: I mean the person who seems a little more knowledgeable and a little bit further inside, picking the best there is and convincing me to listen, murmuring in my ear as I drift off to sleep.

Photograph by Doug Wilson, Flickr CC.

July 26, 2011

Miss Popularity

Here's a habit I never thought I'd develop: I gravitate to anything online that's marked "most popular" or "most e-mailed." And I hate myself a little bit every time I do. I hold a conversation with myself each time I feel myself drifting toward those tempting lists. Why, I wonder, should the popularity of a news story matter to me? Does it mean it's a good story or just a seductive one? Isn't my purpose on this earth, at least professionally, precisely to read the most unpopular stories? Shouldn't I ignore this list? Shouldn't I roam through the news unconcerned and maybe even uninformed of how many other people read this same news and "voted" for it? (Also, I read the news very early. Who are these insane people who read it even earlier than I do and immediately start e-mailing it around and tweeting it and linking to it? Or is the earliest-morning "most popular" list based on the enthusiasm of, say, one night copy editor who forwarded a story to his mom?)

But in the end, I'm afraid, this internal conversation goes quiet and I race to see what made it on the most-popular list. As I do, I wonder if this is one of those instances where the ability to know something has made it seem like something worth knowing. In the past, it would have been very hard to count the number of times a story was clipped out of the paper and given to friends or mentioned in conversation. Technology has made it very easy to collect those statistics. Does that mean it's important to know them, or just cool to know them, or is it just cool that we have the means by which to know them?

What's funny is that the idea of popularity—even the use of the word "popular"—is something that had been mostly absent from my life since junior high. In fact, the hallmark of life after junior high seemed to be the shedding of popularity as a central concern. And here it is back again, and just as it was in junior high, it is irresistible. As much as I turned up my nose at those lists when they first started appearing on news and magazine sites, I can't help but look at them now. Sometimes they contain a nice surprise, a story I might not have noticed otherwise. Sometimes they simply confirm the obvious, the story you know is in the air and on everybody's mind. Never do they include a story that is quiet and ordinary but wonderful to read.

And what about if you are a, ahem, content provider? What if it's your work that is being voted on in the popularity contest? Be honest: only someone with superhuman power could resist noticing when a story he or she has written makes the list, or doesn't. What I wonder is whether the apprehension of that vote will change what we think of writing about. No one—not even junior-high-school graduates—likes to be unpopular, after all.

July 21, 2011

Chicken Chores

My day begins with chicken chores. I allow myself coffee, and then I stumble out of the house in my pajamas and a pair of muck boots, hauling a five-gallon container of water. Keeping animals, I have learned, is all about water. Who even knew chickens drank water? I didn't, but they do, and a lot. A bigger, fancier farm might have a water line directly to its chicken coop, but mine doesn't, so I am the water carrier, lugging as much as I can carry from the spigot at the back of the house to the coop. In the summer, the birds guzzle everything they can, so I carry two five-gallon water dispensers for them, then make a third trip to fill a bowl for the ducks to slosh in. Discovery: water weighs a lot. Other discovery: no need to use free weights when you're carrying ten gallons of water back and forth.

In the winter, it gets more complicated, with heated stands for the water dispensers, and the slickest ice you have ever seen made by the water the ducks (world's sloppiest drinkers) manage to splash around. You would think when it rains my water-carrying would be less necessary, but the rain seems to plunk down everywhere except where it would be useful, and on top of that kicks a mist of mud and gravel into the drinking trough. I dump out the water in the rain and fill it up again.

There's a school of thought that we don't do enough physical labor (see "Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry Into the Value of Work," by Matthew B. Crawford, for one good take on the subject). In my very informal poultry-oriented way, I have come to agree. Even at their messiest and most burdensome these chicken chores please me. It's a concrete need—water!—to which I can respond specifically—here you go, birds, water!—and the cycle is complete. (Until they need water again, of course.) In so many endeavors, including writing, you are never done, and nothing is ever perfect; you are haunted always by the possibility that you could have done more and better. It is a relief sometimes to take on a task and see it through and know it to be wholly sufficient.