Laird Barron's Blog, page 2

March 12, 2018

Talking Blood Standard on the Lovecraft eZine Podcast

Thank you to Mike Davis for having me on the show to talk with the gang. Phil Fracassi spearheaded a conversation about my forthcoming novel, Blood Standard; Philip Gelatt’s film, They Remain, an adaptation of my story, “–30–“; favorite horror films and books; and a lot more.

Art by Jeanne D’Angelo

Art by Jeanne D’Angelo

Talking Blood Standard on the Lovecraft Ezine Podcast

Thank you to Mike Davis for having me on the show to talk with the gang. Phil Fracassi spearheaded a conversation about my forthcoming novel, Blood Standard; Philip Gelatt’s film, They Remain, an adaptation of my story, “–30–“; favorite horror films and books; and a lot more.

Art by Jeanne D’Angelo

Art by Jeanne D’Angelo

February 6, 2018

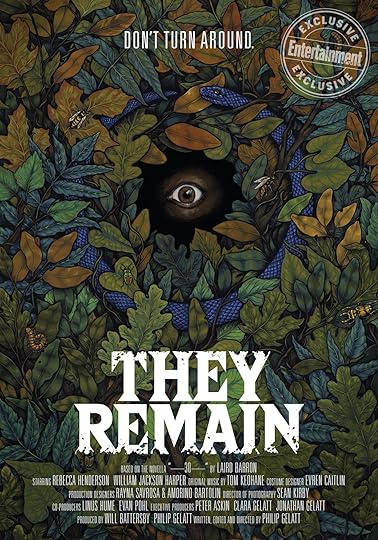

EW Trailer for They Remain

The film will screen in NYC on March 2: Entertainment Weekly trailer for They Remain

image via Entertainment Weekly (art by Jeanne D’Angelo)

image via Entertainment Weekly (art by Jeanne D’Angelo)

January 29, 2018

The 405 Interview

Thank you to Wess Haubrich of The 405 for the chance to talk about film and literature. In this interview, we discuss Charles Manson; my upcoming novel, Blood Standard; the state of contemporary weird fiction; and Phillip Gelatt’s adaptation of my novelette “–30–” into a feature film called They Remain.

[image error]image via The 405 and They Remain film

January 24, 2018

This Is Horror Interview Part 1

Thank you to Bob Pastorella and Michael David Wilson for having me on.

image via This Is Horror and Ellen Datlow

image via This Is Horror and Ellen Datlow

January 20, 2018

Another Me

Here’s a piece I did for Unwinnable #84, the Monster Issue.

Featuring work by Stephen Graham Jones, John Langan, Orrin Grey, Ross E. Lockhart, Gemma Files, Philip Gelatt, Scott Nicolay, Michael Calia, and Livia Llewellyn.

Another Me

by Laird Barron

doppelgänger

noun dop·pel·gäng·er \ˈdä-pəl-ˌgaŋ-ər, -ˌgeŋ-, ˌdä-pəl-ˈ\

1 : a ghostly counterpart of a living person

2a : double

–Meriam Webster Dictionary

Meet the other me, is what the killer allegedly wrote in a text to his friend. Psycho and pal were arguing over gods know what. Maybe you’ve heard of this dude–a down on his luck strangler drifting through Ohio. Nice fellow. But like those cool reversible European jackets, he had another half.

It didn’t have to go that way. He might as well have said, meet another me. But it’s no surprise some of us get a raw deal, in this life and all the rest.

###

–I saw you on the train tracks. Course I’m sure. The hell were you doing on the tracks anyway?

###

I was thirty-one when my left eardrum popped and sent a wet strand of vitreous pearls along my jaw. I took a knee as the world canted off its axis. Then I took myself to the hospital for a brain scan. A technician shot me full of radioactive dye and helped me into an open-lid coffin. The machine’s coil knocked like a rubber-jacketed sledgehammer for the next forty-five minutes. According to the doctor, the scan didn’t reveal anything of note—no obstruction, no tumor, no answers regarding permanent deafness on my left side. He brusquely revealed the scan on a light board and ushered me from his office at the earliest opportunity.

During a follow-up consultation, my girlfriend requested a copy of the image. A former art major, she intended to use the brain scan in some macabre installation. The doctor declined, citing some obscure regulatory protocol. She pressed. The doctor remained icily polite, but I recall the glitter of sweat on his forehead and how his hand trembled as he shuffled files.

There was a moment in the parking lot, as yellow leaves rushed around my ankles, and a kid with a blower roaring across the street, that every sound hit me in stereo. The binaural sensation lasted for a moment before the omnipresent tinnitus drone returned forever.

Well, forever except for moments of weakness. Yeah, there are moments I hear everything crystal clear.

###

–Hey man, what were you doing in Gas Works Park at 5 A.M.? Don’t you live in the U?

###

I celebrated my twenty-first during the annual Iditarod sled dog race with a shot of blackberry brandy from the flask of a great Alaskan adventurer who has since died and more’s the pity. Several days and a few hundred miles down the trail, a blizzard howled down from the north and pinned me and my team of huskies on the shore of Norton Sound among the Topkok hills. Those are big, treeless hills blasted down to tough scrub brush, rock, and a jagged rind of ice.

We were trapped for thirty-six hours. Occasionally, as I hunkered inside the sledbag, I dreamed that the storm lifted and we’d made it across the finish line on Front Street in Nome. Wind slapped me awake. It sucked the heat from lungs and wicked those dreams out of my head. The cold wrapped around me, crawled inside me, froze the socket of my right eye, froze my asshole tight as an uncovered spigot on the side of a house, froze my face so the skin later sloughed like a rubber mask, froze my foot until it click-clacked on the hospital tile like Fred Astaire in tap shoes.

Years and years later, I dream I’m back there, that none of us made it through the blizzard. When I snap awake to the warmth of my bed, I stare at the black window and listen for the roar, because for a few moments it’s easier to believe I’m dead.

###

–Dude, I honked at you on the street the other night. You grinned and slipped into an alley…What’s that all about?

###

My father joined the United States Marine Corps in the latter 1960s. He almost died twice in Vietnam.

First occasion, his platoon was ambushed in a shelled-out village. The enemy opened up with a machine gun. Bullets knocked holes in an old stone wall on either side of him. Several of his fellow soldiers were killed.

Second occasion, the enemy walked mortar rounds onto a camp where my father’s company had dug in. Everybody scrambled for a hand-dug bunker under the mess tent as the explosions thudded closer and closer. A round detonated somewhere behind Dad. He sprawled onto his belly as some death god swiped its claws through the tent and a fan of shrapnel left the canvas in tatters. Telling the tale, he always claimed his two tours were the most fun he’d ever had.

Mom got into a nasty argument with Dad and she said he should have stayed in Vietnam if he loved it so much. He laughed and said, Well, honey, I did.

###

Baby, I know you were in California. I’m telling you—I rolled over and saw you smiling at me from the closet. Hell yes, I screamed. Woke my mother. Actually, it wasn’t you. Just your head.

###

Dad was a slave to his moods. He reveled in coarse humor and homespun philosophizing. His anger was a terrible sight, but he remained human, he remained Dad. He lost much of his hearing from the gunfire and explosions during the war. Around age thirteen I came upon him in the woods one day as he cut a trail with his doublebit axe. He hadn’t expected me, hadn’t expected anyone since we lived in the woods and our nearest neighbors were twenty miles or so down the river. This was late October and the ground had frozen. I scuffed my boot on some ice.

He must have wheeled, although I don’t recall him doing so—one second he gazed into a copse of black spruce, and then he faced me, his spine bunched, the axe handle held loosely in both hands, ready to swing. His blue eyes drained to match the gray landscape. He didn’t resemble anybody I knew. He wore a cheap human mask—pale and stiff and dead. I used to tell myself that was Dad’s war face.

Better believe I watched him after that. Sometimes I spied as he snoozed in the big recliner he referred to as his throne, or when he thought himself alone and unobserved in the backyard. Now and again, I’d see the other guy, the actor who replaced him on certain occasions such as when he and Mom discussed slaughtering an animal or why they’d been stupid enough to go for three kids.

Or maybe it was the other way around.

###

–Check the dude in the corner. Swear that sonofabitch is the one who ripped me off last winter. Stuck a gun under my chin and took my dope and all my cash. Gotta be, gotta be. Naw, I ain’t talkin’ to him. Motherfucker is scary. For real, bro. That’s him or it’s his fucking twin.

###

People swear they’ve seen me. I get it often enough, I smile and shrug and say, Ah, my doppelganger. He intercepts my royalty checks. The bastard!

Not everybody smiles back. You don’t understand, I saw you. At night on desolate corners; in the branches of a tree, waving to traffic; pale and grinning from the window of a passing bus; smirking behind a rack of clothes in a closet; in a foxhole in Korea; and countless half-remembered nightmares. I guest star in plenty of those.

My own favorite recurring nightmare goes like this: I trudge along a sidewalk in Seattle’s University District. It’s dark. Someone is following me. They duck behind a hedge or a mailbox whenever I glance over my shoulder. The sidewalk and the sodium lamps unspool into infinity. Just as I reach to unlock my apartment door, somebody whispers my name and I fly awake. It’s my voice.

###

I feel as if I never really knew you.

###

Sometimes, out of the blue, the old, old dog raises her head and stares at a spot over my shoulder. Her ears will prick up and she’ll bare her fangs and emit a low, rumbling growl reserved for danger and situations her doggy mind can’t comprehend. Maybe to her, it’s the same thing.

Her rheumy eyes reflect my shadow. And sometimes, sometimes, I don’t love her with a loyalty borne of shared adventure and hardship. Yeah, in those rare instances, I don’t feel anything for her at all. I feel as cold and hollow as the vacuum in the wake of an arctic gale.

Then somebody whispers my name, or I imagine they do, and it passes. I’m myself again.

January 8, 2018

Janet Reid Q & A

Straight Talk From Janet Reid over at the Insecure Writers Support Group. When it comes to clear-eyed discussion of the dos and don’ts, customs, trends, and protocol of writer-agent relationships, none are more forthcoming than Janet Reid. Her blog is a treasure trove, especially if you’re a newer writer seeking to demystify the process of submitting to and landing an agent–and what to expect once you’ve succeeded.

December 31, 2017

Crime Fiction Lover’s Wanted List

Thank you to Crime Fiction Lover for including Blood Standard on their most-wanted crime books of 2018. The Nakamura looks like my thing.

image via Crime Fiction Lover

image via Crime Fiction Lover

Meanwhile, I’m reading some classics, such as John D. MacDonald’s The Lonely Silver Rain.

image via Amazon

image via Amazon

December 20, 2017

The Black Barony 1.

A couple of years back I wrote this essay for Dark Discoveries as a feature of my Black Barony column. Images via Amazon.

The Golden Age of Dread

by Laird Barron

The Sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out;

At one stride comes the dark

–Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Past Is Prologue

Let me tell you something of myself and why the macabre and the strange fascinate me. I have an old and abiding relationship with Horror and weirdness. We go way back, and whether I knew it or not, the Weird has always loomed large in my intellectual life.

I come from a family of storytellers. Many of my father’s and grandfather’s generation, semiliterate or educated, cleaved to oral tradition. Granddad tried and failed to sell novels. An uncle on Mom’s side wrote psychedelic poetry and song lyrics. After we moved from the 1970s Alaska version of the suburbs to a homestead in the sticks, Dad often told us kids elaborate bedtime stories.

The old man’s repertoire was scary stuff on the whole—he delved into his own childhood growing up in rural Texas and Alaska during the ‘50s. He spun yarns of fantastical brushes with the uncanny and inexplicable. Other stories were recycled and repurposed plotlines of films—The Thing; An American Werewolf in London; The Shining; and so forth. His reworked tales would start with something along the lines of, “These three kids, brothers, got turned around hiking near Moose Pass. So they went into a nameless tavern where a snarling, bloody-jawed wolf’s head adorned the shingle…”

He saved the spookiest, most unnerving material for our teen years. The years of heavy responsibility—good old Dad frequently absconded with Mom via riverboat, dog team, or airplane, to civilized locales, leaving us boys to fend for ourselves for days, and occasionally weeks, at a stretch. By twelve, I knew how to cook for my brothers, feed a kennel of huskies, chop wood, shoot a rifle, and all the other details required to maintain a cabin in the middle of nowhere during deep winter. Dad was by no means a literary critic. He liked what he liked, end of story, so to speak. On a primal level, he understood that Horror stories are cautionary illustrations, similar in purpose to fables, but weighted toward the “what would you do if…?” side of the scale. What would my brothers and I do if, while alone at the cabin, we heard a stranger calling for help down the path to the river where the bushes grow thick and the shadows are deep? What if the huskies growled and their hackles stood up? What if one of us went missing? What if the TV died and the CB radio transmitted nothing but static and no one came for us? You get the idea.

The tiny, battery-powered black and white TV was a luxury for a few of my formative years. Happily, we’d lugged a decent-sized library out into the boonies. Materials covered the spectrum from Barbara Cartland to Louis L’ Amour; from Asimov to Zelazny; and Robert Browning to EA Poe. I first encountered the Weird as a third-grader when Robert E. Howard’s Conan books fell into my clutches. Those Lancer/Ace editions from the latter 1960s and 70s of the ass-kicking Frazetta covers. “Red Nails,” man. The renaissance of the Conan line is almost enough to convince me that editor/authors L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter were good for something. Conan understood the Weird, and for the most part he hated it, unless it benefited him, and even then. For Conan, the most positive attribute of weirdness was that if it manifested in the mortal realm it could be defeated through a liberal application of cold steel.

Edgar Rice Burroughs was another early favorite of mine. Burroughs also dabbled in certain aspects of the Weird. John Carter proved a bit more temperate regarding the collision of the mundane and the inexplicable. However, he too defaulted to the maxim that no matter what polychromatic pigment or number of extra limbs an enemy possessed, a few stabs from something pointy would remedy all ills.

And of course, I’m on record as a lifelong fan of Roger Zelazny, a writer who focused on science fiction and fantasy yet assayed brief forays into Horror and strangeness. He remains a strong inspiration in terms of style. However, when it comes to my preoccupation with the macabre, Edgar Allan Poe is the bad seed that started it all. Not only for me, not only other writers of the dark, but practitioners of related genres as well. As I’ve remarked elsewhere, Poe’s profound influence upon me never became clear until I reflected upon the role live burial and incipient madness recur in my own work. As it happened, I’d torn through collections of Poe’s poetry and fiction throughout childhood and integrated some of his exquisite melancholy and dreadful paranoia into my subconscious.

Despite the madness, murder, doping, boozing, sex, and general mayhem, Poe was A-Okay with my hawkish evangelically-minded mother. The classics got paid a bit of slack, fortunately, because Poe was all I had of the really subversive stuff for quite a while. It wasn’t until mid to late adolescence that I dug into the special stock of modern Gothic Horror my parents kept under lock and key. We’re talking Thomas Tryon, William Peter Blatty, Ira Levin, and Stephen King. Now were really cooking—The Other; The Exorcist; Rosemary’s Baby; and The Shining. My literary education had entered a new phase. The wonderful world of occultism and possession Horror.

Suffice to say, I survived and came through intact, a mild penchant for the diabolical notwithstanding.

Bizarro and The New New Weird

The Weird has been with us always; it existed as a dominant force, and a defining force, long before genre categories were officially delineated. I have argued elsewhere that it predates written history and likely originated around a fire in a cave. The Weird is, arguably, the parent category from which Horror derives. Consider also certain elements of creation myth. Consider outré elements of historical accounts such as Alexander’s eastward journeys toward Terra Incognita. Consider more modern artists and their works, such as “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Coleridge, a composition enameled with rococo bizarreness and black glints of cosmic Horror; and the chilling re-imagining of Biblical lore in “Lazarus” by Leonid Andreyev; or the seminal “Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

New Weird is a popular neologism at the moment, albeit contested and of questionable utility. The term materialized during the first three or so years of the Aughts; favored oath of authors such as China Mieville, M. John Harrison, and Jeff VanderMeer. Jeff and his wife Ann subsequently partnered on an anthology project titled The New Weird. Headlined by Mieville and Jeff Ford among other luminaries of modern fantasy it represented a worthy stab at the beast of Weird fiction, but like the eponymous movement, it fell flat as a defining statement. It lacked an intrinsic sense of coherence.

Infinitely better and infinitely more useful was the duo’s follow-up anthology, simply titled The Weird—a mega omnibus collecting Weird tales from 1908 to 2010. This is an epic anthology and representative of the best that literary fantastica and strangeness has to offer. The anthology’s success and scope is also demonstrative that the New Weird, while catchy, merely flashed in the pan and the minds of a subset of authors and booksellers intent upon creating a marketing niche.

As Horror exists along a spectrum, the Weird also spawns its share of subsets, including MR James Christmas terrors, the paranoid fantasies of Shirley Jackson and Robert Aickman, and Thomas Ligotti’s hallucinogenic transfigurations of corporate toil. Bizarro fiction is the latest and possibly boldest niche to be carved in the modern canon. Cut from the same dark-matter cloth as Burroughs and Kafka and intended as literary peyote or a psychedelic eye-skewer that combines absurdism and Horror and sets the concoction ablaze, Bizarro crept among us somewhere during the latter 1990s and metastasized. By the mid Aughts it had, like some kind of brain-hijacking Cordyceps spore, taken over a segment of the publishing hive mind.

Inasmuch as the independent press deserves recognition for the proliferation of readily available dark literature in general, the folks at Eraserhead Press, Lazy Fascist, and Raw Dog Screaming Press were the original fire starters who continue to promote some of the most experimental work around. Cody Goodfellow, Robert Jeremy Johnson, and Cameron Pierce are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to this particular movement. I highlight them because they have taken the pioneering concept of this insanely mutable and highly unstable genre and harnessed it to remarkable effect. In the beginning there was plenty of light; at last, these folks are generating heat to match. Couple the dedication to craft with a well-timed stunt or two, namely Patrick Wensink’s novel Broken Piano for President whose cover art earned a pleasant cease and desist from Jack Daniels corporate suits, and backed by a plenum of editors and publishers intent on a mission, and you’re on to something.

I’d be remiss not to provide a coda for this segment. The demarcations between various genres and genre communities aren’t always clear, especially when it comes to the Weird. Bizarro is even trickier when it comes to territorial and tribal distinctions. Off blazing their own trails, but perhaps erroneously associated with Bizarro, are numerous operators of the interstitial realms. I’ll hit you with three: Molly Tanzer, Nikki Guerlain, and Anne Constance Fitzgerald. Read them—any or all could be the next big thing.

Contemporary Stylings

Much of the current richness of the field is attributable to a shift that occurred on one side or the other of the year 2000—the small press began to yoke the awesome power of the internet and as a result, everybody prospered, especially readers who gradually were introduced to a veritable banquet of choice unequalled in modern history.

When I started paying close attention to the scene back in then, internet message boards were the prime watering holes—many of us remember the Night Shade and Shocklines BBs via a mixture of nostalgia and nausea. Mostly nostalgia for me, especially in regard to Night Shade. That’s where I made the acquaintance of several of the foremost fantasists of our time. In those days, Jeffrey Ford, Ellen Datlow, and Lucius Shepard frequently held forth on the subject of their latest publishing ventures, movie reviews, and convention plans. The fuming cauldron of semi-public shop talk and kibitzing on everything from the state of the genre to the state of the union wasn’t fated to endure. People drifted to Live Journal, Twitter, and the great Mammon reborn, Face Book. Great enlightening fun while it lasted though.

While that maelstrom of message board-churning was in progress, unsung hero of the moribund Horror field, Brian Keene, launched a predawn attack: he singlehandedly revived the giant monster and zombie contingent a la The Conqueror Worms (Earthworm Gods) and The Rising. As I write this in October of 2015, zombies continue to run amok in novels, video games, and cinema. The walking dead get all the glory, yet it’s the Technicolor widescreen madness (and yes, pants-shitting weirdness) of Keene’s Conqueror Worms/Earthworm Gods cycle that should be enshrined, if for nothing else than their prescience regarding cataclysmic climate change, concomitant weather disasters, and renewed popularity of enormous, planet-wrecking monsters (see Pacific Rim and Attack on Titan).

Recently, Neo Noir, or the New Black, has attracted attention. Yes, another fresh neologism; although similar to Bizarro, Neo Noir makes a stronger case for itself than the New Weird has done. There are simply more authors and editors involved and their aim is concentrated, more refined, more of a coherent vision. Be that as it may, critics, scholars, and history will get the last word. Regardless of what one might prefer to label it, some of the finest mashups of genre have resulted from this experiment. The New Black, edited by Richard Thomas, is a stunning example of hybrid literature that skews to the dark side. Much as I enjoy the New Black and its renovation of familiar architecture, my hat is also off to the writers who were there first. Norman Partridge and Joe Lansdale blazed this trail for many moons—fusing crime and horror and pure weirdness with a uniquely North American hardboiled panache. One detects their influence upon the likes of Richard Thomas (whose debut novel Disintegration is a fine example of this kind), Stephen Graham Jones, Molly Tanzer, and Benjamin Percy.

The amazing and painful thing of it is, we are experiencing such a surfeit of riches, it’s impossible for my essay to completely touch upon the era’s essential authors, filmmakers, and publications, much less examine them rigorously. The inimitable Michael Cisco unleashed The Narrator and The Divinity Student upon us; two seminal novels that exemplify the very definition of Weird fiction, while Koji Suzuki’s Ringu trilogy, less than a decade old, was joined by Ju-On and various titles by Takashi Miike (Audition, Ichi the Killer, and Gozu) at the fore of the J-Horror invasion of the States. Adam Nevill’s work rises like a black star over Britain even as Kaaron Warren, Leena Krohn, and Karin Tidbeck push the envelope in Australia, Finland, and Sweden respectively.

Grand old men of the field Lucius Shepard and Michael Shea left us forever, and Thomas Ligotti effectively retired from fiction; but S.P. Miskowski published the Skillute Cycle, Gemma Files came into her own with numerous lauded short stories, Victor LaValle and Glen Duncan smote us with modernizations of the Minotaur and werewolf, Mike Allen, among the most dynamic of contemporary fantasists, habitually upends Lovecraftian tropes with his own brand of cosmic horror, Livia Llewellyn blew our doors off courtesy of her gloriously grotesque debut, Engines of Desire (one of several important authors published by Steve Berman at Lethe Press), and Wilum Pugmire puts forth a new baroque masterpiece every other year. And the beat goes on, and on.

Great as this age’s writers may be, invaluable as the publishers are to the process, the lynchpin that keeps disparate elements united is undeniably the yeoman labor of the editors. The editors who work the trenches now are the equal of any group from the Halcyon days of yore, and I’ve had the privilege to be shredded, then mended by a number of these good people. However, no modern anthologist (and the anthology has proven to be the heavyweight game-changer of Horror and the Weird) has endeavored more, or struck a harder blow, for the advancement of macabre fiction than Ellen Datlow. Her work at Sci Fiction and on numerous anthologies over the past decade and a half, produced a who’s who and what’s what list of major award-winning stories. Inferno, Lovecraft Unbound, and Poe stand as modern classics. These anthologies represent a mere fraction of the terraforming effect Datlow exerts at this very moment upon the genre landscape.

Golden Age of Dread

The weather has turned in favor of Weird fiction and Horror. A veritable ice age that spanned the ‘90s into the early Aughts has mellowed and faded. This is, in itself, nothing new. Literature has seemed to ebb and flow in popular currency over the past few decades, contracting precipitously after the collapse of the US publishing economy, and certain genres suffered moreso than others. Happily, the wheel continues to turn and thus old is made new.

Behold the evidence of a literary thaw and what the receding glaciers reveal: Bizarro has gradually emerged as a viable force with the advent of Carlton Mellick III’s Clownfellas published by Random House. The smash success of cable series True Detective shone the spotlight on old masters of the Weird, namely Robert Chambers, and contemporary practitioners Thomas Ligotti and John Langan, among others. The possession genre received a shot in the phantom arm following the success of Paul Tremblay’s chilling novel A Head Full of Ghosts, soon to be a major motion picture starring Robert Downey Jr. And for unvarnished, full-bore weirdness, one need look no further than Jeff VanderMeer’s bestselling Southern Reach trilogy, also optioned for film.

Some authors and critics have termed this recent positive trend a renaissance, others call it a revival, and still others claim it is evidence of a specific movement. I prefer to regard the resurgence as a golden age of darkness, a golden age of dread, a golden age of the Weird, which encapsulates these themes and more. The age of Bizarro, the so-called New Weird, the age of small presses, e-zines, and adventures in self-publishing.

This tide has crested before: in the colonial era of Poe, Hawthorne and Bierce; later on during the heyday of Clark Ashton Smith, Machen, Blackwood, Burroughs, Howard, and Lovecraft; during the 1950s and ‘60s when Shirley Jackson, Flannery O’Conner, and Ray Russell rode high; unto the rise of the occult in the ‘70s; the big hair and bigger scare ‘80s that witnessed the primacy of Michael Shea, Peter Straub, Joyce Carol Oates, Stephen King, and Clive Barker; and most recently the likes of Koji Suzuki, Yoko Ogawa, Brian Evenson, Conrad Williams, Paul Tremblay, and John Langan whose terrors defy the onset of global surveillance and instant technology.

The small and independent presses in harmony with the transformative nature of social networking, have collaborated to usher in an era unrivaled for the quality and ubiquity of macabre literature. Mainstream press, such as SLATE, SALON, and The Wall Street Journal lend the topic column inches on a regular basis. Let me tell you brothers and sisters, in a wilderness of fractured and segregated media and entertainment, that’s enormous.

In 2007 I wrote an article for LOCUS on the state of Horror and by relation, Weird fiction. I referred to the state of the union as a golden age and if anything, it remains on the ascent. The genre is in a terrific place at the moment. Where are we headed? Despite economic uncertainty, the constant fragmentation of entertainment sources and increasing competition from television and video games, we who toil in the field persist and we thrive. We continue onward, with our little candle, into the night.

December 13, 2017

Read Matthew Bartlett

Read Matthew Bartlett. Spettrini at the Weird Fiction Review is a good place to begin.

Then go buy one of his books. Perhaps Creeping Waves.

image via Amazon

image via Amazon