Fuchsia Dunlop's Blog, page 5

October 10, 2013

Fancy a buckwheat noodle enema?

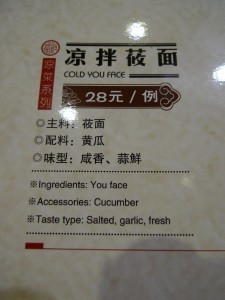

I know it’s something of a cliche to giggle at Chinese menu mistranslations, but the menu I came across at lunchtime today was such a spectacular disaster that I had to share it! Here are some of the linguistic catastrophes on offer in a Shanxi restaurant in Beijing:

I know it’s something of a cliche to giggle at Chinese menu mistranslations, but the menu I came across at lunchtime today was such a spectacular disaster that I had to share it! Here are some of the linguistic catastrophes on offer in a Shanxi restaurant in Beijing:

荞面灌肠 Buckwheat noodles enema [unfortunately the same Chinese characters are used for an enema and some sausagey-type things]

凉拌莜面 Cold you face [here, the dish is cold oaten noodles, but the character for noodle-type foods (mian) is the same as that for face; and clearly they couldn't find oats in the dictionary so they didn't bother to translate and just gave the pinyin transliteration of the character, 'you']

老醋烧带鱼 Vinegar burning octopus [the character shao can be translated both as 'burn' and as 'braise/cook': the translator clearly got confused here. Mysteriously, the main ingredient isn't octopus at all, but hairtail fish.]

群英香爆天鹅脯 Beat hong explosion swan preserved [this really is apparently made with swan, but they made that old mistake of confusing one of the meanings of bao, 'explode', with another, 'fast-cook at high temperature'. I've no idea where 'beat hong' came from, because I think the first two characters mean 'a group of distinguished heroes']

红面剔尖 Red-faced tick tip [??? this is their name for a kind of pasta made by scraping shreds from a mass of dough with a bamboo implement]

豌豆面抿蝌蚪 Peas face sip tadpoles [They've confused noodle-type foods with 'face' again, and although these little squiggles of pasta dough are known poetically as 'tadpoles', the scrambling of the rest of the sentence makes the name quite incomprehensible.]

At least they’d had the foresight to include photographs of all the dishes on the menu!

September 27, 2013

Pizzle puzzle

How to cook a stag penis? Not a question I’d ever seriously pondered, until I inadvertently acquired four of them, and had to find a way. You can read about my adventures in the latest issue of Lucky Peach or on Buzzfeed here…

How to cook a stag penis? Not a question I’d ever seriously pondered, until I inadvertently acquired four of them, and had to find a way. You can read about my adventures in the latest issue of Lucky Peach or on Buzzfeed here…

Lucky Peach is a little hard to find in the UK, but I know Foyles in London’s  Charing Cross Road stocks it, and you can also buy it on Amazon.

Charing Cross Road stocks it, and you can also buy it on Amazon.

Here is the Amazon link:

September 24, 2013

New York Times recipe lab (+ a note on substitutions)

You can see Julia Moskin and three New York Times readers chatting with me about ‘Every Grain of Rice’ here:

And the full article, focusing on Gong Bao chicken, is here.

A brief note about substitutions:

Shaoxing wine: Cooking wine is widely used by Chinese cooks to refine and purify the flavours of meat, fish and poultry, which is why you find it in marinades such as the one for Gong Bao chicken. The most widely available such wine in the West is Shaoxing wine, which is why you find this listed in my recipes (cooks in Sichuan often use generic liaojiu 料酒 cooking wines which are not necessarily made in the Shaoxing way). Virtually every Chinese supermarket will stock Shaoxing wine, but if you can’t find it, use medium-dry sherry instead, or even omit it from recipes like this where it is used in very small quantities – we are talking refinements of flavour, and the recipe should still taste good without it. Dry vermouth may also be used, although I haven’t tried it myself. (There are, of course, some recipes from eastern China that call for larger amounts of Shaoxing wine, where is used as a key seasoning rather than a tool for refining flavours – and here, you do need the real thing.)

Chinkiang vinegar: Chinkiang (aka Zhenjiang 镇江) vinegar is a famous vinegar from the city of Zhenjiang in eastern China, which is made from glutinous rice and wheat bran. It is a classic type of ‘fragrant vinegar’ 香醋 with many culinary applications, and is widely available in Chinese supermarkets in the West. In Sichuan, cooks traditionally prefer a famous local vinegar, Baoning vinegar, which is made in northern Sichuan from glutinous rice and wheat. Baoning vinegar is hard to find in the West, and Chinkiang vinegar makes a perfectly acceptable substitute, which is why I recommend it in my recipes. I tend to look for Chinkiang vinegar made by the Hengshun brand, because I’ve visited the famous Hengshun factory in Zhenjiang and was impressed by the manager there. Chinkiang vinegar is normally easily available if you have access to a Chinese supermarket or an online store. If you don’t, then do use a regular balsamic vinegar as a substitute in recipes which, like Gong Bao chicken, require small quantities of vinegar. The taste won’t be exactly the same, but you will achieve the desired sweet-and-sour base for the sauce – and I wouldn’t let a lack of Chinkiang vinegar stop you making this dish. I try in my printed recipes to give an authentic version, as made in the source region in China, but like anyone else I often find myself cooking spontaneously in friends’ houses or holiday homes without exactly the ingredients I need, and like anyone else I improvise. A few weeks ago I made a Sichuanese ginger-juice sauce with balsamic vinegar, and although no one could argue it was strictly authentic, everyone found it delicious!

Chillies: Don’t get too hung up on chillies. With Gong Bao chicken, you want a gentle kick of chilli, but the exact degree of heat is a matter of personal choice. I suggest you avoid the lethally hot little Indian bird’s eye chillies, which are too strong for this dish, but do feel free to substitute whatever medium-heat chillies you have available, and vary the quantities if you please. I’ve used facing-heaven chillies, nameless long Indian chillies, Mexican de Arbol chillies and Chinese xiao mi jiao 小米椒 (‘little rice chillies’) in this dish. Again, not exactly as you’d find the dish in Chengdu, but perfectly delectable!

In general, as a writer I try to be faithful to my sources, and give the recipes as I find them in China (or, where I have to make substitutions, explaining this in a headnote). But cooking is a practical, daily life-skill essential to health and happiness, and strict authenticity is not the be-all-and-end-all of preparing food at home. So please, use my recipes as a guide, but if you don’t have exactly every ingredient every time, feel free to play!

Sichuan pepper: There is no substitute for Sichuan pepper, but I don’t see why you can’t make a scrumptious sweet-sour spicy chicken by following the Gong Bao recipe without it – just be aware that it’s not a classic Gong Bao chicken.

P.S. One of the comments below the post about me and my recipe for Gong Bao chicken says the following: “Her recipe, while tasty, is undistinguished… She seems to have been chosen as a featured author not because her recipes are outstanding, but because she is young and good-looking.” I have to admit that this made me laugh out loud! As someone who is neither particularly young nor particularly good-looking, but who has spent many years attempting to fathom the culinary mysteries of China, I’m not aware that I’ve ever previously been viewed as a bimbo who has climbed the greasy pole because of my appearance!! Priceless. I’m not sure whether to be flattered or insulted.

September 21, 2013

News, tapas-style

READING: I’ve been gripped by Anya von Bremzen’s memoir of eating in the USSR, ‘Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking’. The story of three generations of her family and a century of life in Russia (and other parts of the USSR), it’s darkly funny, richly informative and fascinating. The sweet-sour nostalgia for an era characterised by food queues, political doublespeak, black humour and deprivation reminds me a little of China, where some people still reminisce fondly about life under Maoism.

WRITING: A short piece for Financial Times Weekend on the best Shanghainese restaurants in Shanghai – you can read it here.

COOKING: I’ve been trying to improve the elegance of my baozi (steamed buns), with the help of the Sichuanese head chef of Baiwei (the new restaurant in the Barshu group), Fu Bing. Last week I made some stuffed with slow-cooked pork (divine), and some Xinjiang-style with minced lamb and shallot (next time I’ll use some kind of green vegetable rather than shallot), and served them with Sichuanese spinach in ginger sauce and some runner beans from my mother’s garden, simply steamed and dressed with salt, olive oil and lemon juice. I also made Gong Bao chicken, an old favourite that I haven’t made for a while, in preparation for my live video chat with the New York Times on Monday – details here.

COOKING: I’ve been trying to improve the elegance of my baozi (steamed buns), with the help of the Sichuanese head chef of Baiwei (the new restaurant in the Barshu group), Fu Bing. Last week I made some stuffed with slow-cooked pork (divine), and some Xinjiang-style with minced lamb and shallot (next time I’ll use some kind of green vegetable rather than shallot), and served them with Sichuanese spinach in ginger sauce and some runner beans from my mother’s garden, simply steamed and dressed with salt, olive oil and lemon juice. I also made Gong Bao chicken, an old favourite that I haven’t made for a while, in preparation for my live video chat with the New York Times on Monday – details here.

EATING: It’s been a splendid and gluttonous week, for one reason and another.

Pho at Song Que

Sunday lunch at one of my favourite London haunts, Royal China Club. The scallop dumplings here are exquisite, as is the cheung fun. The only disappointment was that one of the specials I always order is no longer on the menu: I can’t remember the official name, but it was those gorgeous little steamed rice paste cups topped with minced pork and preserved vegetable that are a speciality of the Cantonese Chiuchow/Chaozhou region, and which they served here on a bed of steamed egg custard. After we’d eaten I told the head waiter of my sorrow not to see them (!), and he said that they always take customers’ comments into account. So I live in hope!

On Monday my mother and I had lunch at Song Que, where I ordered, as always, the bun (cold rice vermicelli) topped with shredded pork, grilled pork, spring rolls, pickled vegetables, herbs and a nuoc cham sauce; a bowlful of pho, and the grilled beef in betel leaf which has to be wrapped in lettuce leaves eat.

Scallops at Restaurant Story

Monday evening: fabulous dinner at Pollen Street Social with one of the guests from my first China culinary tour with Royal China last year. We particularly enjoyed the soft hen’s egg with truffle puree and smoked eel soup, the hay-smoked quail ‘brunch’ with ‘cereals, toast and tea’, as well as the ‘PBJ’ and ‘Thai flavours’ puds.

The most stunning surprise of the week was Restaurant Story, just south of Tower Bridge. Frankly, I’d expected something a bit twee, but the food was lyrical, exquisite and extraordinary. Of the ten course tasting menu (and assorted snacks to begin and end), only one dish seemed less than perfectly balanced. Staff were enthusiastic and knowledgeable without being intrusive, and the pared-down decor, with undressed wooden tables and none of the frippery that often accompanies food of this craftsmanship, gave the evening a relaxed and delightful air. Top dish? Hard to choose, but ‘Beetroot, raspberry and horseradish’, ‘wild duck, apple and bilberry’ and ‘almond and dill’ were hot contenders.

Anyway, after all that, it’s back to real life – which fortunately involves plenty of home-cooked Chinese food.

LISTENING: Leonard Cohen at the O2, still enthralling an arena filled with thousands at the age of 78. What can I say? Just a joy.

September 13, 2013

Anyone for chop suey at the Chinese Delmonico?

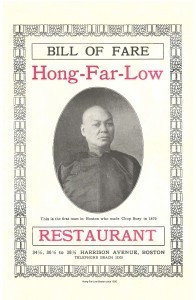

Thanks to Cool Culinaria for sending me samples from their new collection of vintage Chinese restaurant menu prints, which date from the late nineteenth century to the 1970s! The originals come from the Harvey Spiller Collection, which is apparently the largest privately-owned Chinese menu collection in the world. They offer a fascinating glimpse not only into the food, but the imagery used to sell Chinese food in America, including ‘chop suey’ fonts and dragons. Two early examples particularly caught my eye. The cover of the Bill of Fare from the Hong Far Low, a restaurant in Boston in the 1930s, displays a black-and-white photographic portrait of a serious-looking man in a traditional Chinese gown with cloth fastenings, who is described as ‘the first man in Boston who made Chop Suey in 1879′. The menu itself is only in English and clearly aimed at American customers, with sections on fried chicken, chicken chop suey, chow mein fried noodles, chop suey, omelets and salads, and a collection of very unChinese-sounding desserts, such as chocolate cake.

Thanks to Cool Culinaria for sending me samples from their new collection of vintage Chinese restaurant menu prints, which date from the late nineteenth century to the 1970s! The originals come from the Harvey Spiller Collection, which is apparently the largest privately-owned Chinese menu collection in the world. They offer a fascinating glimpse not only into the food, but the imagery used to sell Chinese food in America, including ‘chop suey’ fonts and dragons. Two early examples particularly caught my eye. The cover of the Bill of Fare from the Hong Far Low, a restaurant in Boston in the 1930s, displays a black-and-white photographic portrait of a serious-looking man in a traditional Chinese gown with cloth fastenings, who is described as ‘the first man in Boston who made Chop Suey in 1879′. The menu itself is only in English and clearly aimed at American customers, with sections on fried chicken, chicken chop suey, chow mein fried noodles, chop suey, omelets and salads, and a collection of very unChinese-sounding desserts, such as chocolate cake.

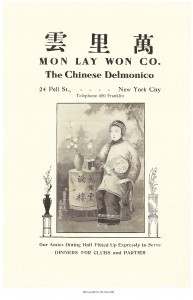

The Mon Lay Won Co on Pell Street in the Chinatown of New York City bills itself as ‘The Chinese Delmonico’. On the front of its rather charming menu (c. 1910) is a reproduction of a painting of an elegant lady in Qing-style embroidered robes, with a silken fan in her hand and one elbow resting on a small table bearing a vase of plum blossoms, apparently commissioned by the proprietor, according to the inscription (為萬里雲主人高橋孤泉画). Two small engravings of flower vases on ornamental tables frame the main image.

Chinese Delmonico’. On the front of its rather charming menu (c. 1910) is a reproduction of a painting of an elegant lady in Qing-style embroidered robes, with a silken fan in her hand and one elbow resting on a small table bearing a vase of plum blossoms, apparently commissioned by the proprietor, according to the inscription (為萬里雲主人高橋孤泉画). Two small engravings of flower vases on ornamental tables frame the main image.

The actual food on offer here is grander and more Chinese than at Hong Far Low – although there is plenty of chop suey to satisfy American customers. For two dollars, one could have a dinner of ‘Bird’s Nest Soup, Bass Pekin Style, Shrimp Omelet a la Chinese, Roast Squab, Chicken Mushroom, Mushroom Chop Suey, Boiled Rice’ followed by a dessert of ‘Li Chee, Golden Limes, Canton Ginger, Lin Som Tea’. The a la carte menu lists Beche-de-Mer (aka sea cucumber), dried oyster soup, giblet soup, ’pigeon pique’, various kinds of rice congee and pig’s feet. Quite a few Chinese vegetables are offered, with their transliterated Chinese names, including Kai Choy (mustard greens), Sz Kwa (silk gourd) and Tung Kwa (winter melon), alongside a selection of teas: Oolong, Souchong, Congon,  Sui Sin Cha, ‘Loong Su or Dragons Beard’, Pow Chong, Hung Muey and Heung Cha. ‘Chinese condiments and Preserves in great variety’ and ‘Pang’s Celebrated Chinese Cigarettes’ are also available. Patrons are reminded that the establishment can cater for private dinner parties on request.

Sui Sin Cha, ‘Loong Su or Dragons Beard’, Pow Chong, Hung Muey and Heung Cha. ‘Chinese condiments and Preserves in great variety’ and ‘Pang’s Celebrated Chinese Cigarettes’ are also available. Patrons are reminded that the establishment can cater for private dinner parties on request.

Two particular questions spring to my mind: 1) Are the sea cucumbers, pig’s feet and abalone aimed at adventurous Westerners or at Chinese customers? Or perhaps partly at Chinese customers entertaining Westerners to dinner? Was bird’s nest soup an important part of the exotic experience of eating Chinese food, just as Sichuanese chilli-laced tripe might be for more daring diners-out today? Or was it regarded as bafflingly foreign? 2) Did restaurants such as Mon Lay Won and Hong Far Low have supplementary Chinese-language menus for their Chinese customers as some Chinatown restaurants still do today? Were they offering off-menu specials and seasonal foods to Chinese customers? Was the food as sophisticated as it sounds? (Only more accomplished chefs would normally cook expensive ingredients like shark’s fin and sea cucumber.)

Some answers here, in a blog post by Jeff Weinstein, with some old photographs of Mon Lay Won. More pics here. And a very interesting post, too, in Flavor and Fortune, Jacqueline Newman’s specialist journal about Chinese culinary culture, which is by Harvey Spiller, menu collector extraordinaire, himself.

While we’re on the subject of Chinese food in America, may I again recommend Andrew Coe’s brilliant ‘Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States’ – richly informative and a delightful read. Here’s a link, in case you’d like a copy:

Finally, here’s the poem from the ‘Chinese Delmonico’ menu, by the proprietor, Jimmie:

My bird’s nest soup is first, of course;

On top of this, black fish with sauce,

Nice rich omelet, a la Chinese

Luscious roast squab with brown gravy,

A fried Shark fin from the Yellow Sea

You next take Chicken with mushrooms free.

Wonderful Chicken roasted and brown,

Order Li Chee nuts, best in town,

Nice golden limes, or fresh green plums.

Choice pineapple, will you have some?

Oolong tea or rice wine free,

My Bill of Fare is first, you see.

Please try our cakes of sponge or rice,

A dainty treat, you will find them nice

No other place has a menu, hither or yon,

You can compare with the MON LAY WON.

September 7, 2013

A Devon idyll of cakes, cooking and conversation

Totleigh Barton

I’m just back home after a week of intensive teaching and eating in Devon, where writer, designer, cook, photographer and restaurateur Alastair Hendy and I were running a food-writing course for the Arvon Foundation. We and thirteen students were let loose in Totleigh Barton, an ancient thatched house filled with books, with no television or radio and virtually no telephone or internet access. On all Arvon courses, lunches are provided by visiting staff, but dinners are cooked by whichever group of writers is in residence, and everyone fixes their own breakfast as and when they choose. Normally, the Arvon people provide recipe cards and suggested menus for the dinners, but with a food-writing group that included accomplished amateur and professional cooks… well, as you can imagine, we were largely left to our own devices, which meant that we feasted like kings for four days.

Wine-poached pears with blackberries

On the first day we pillaged the kitchen garden for radishes, lettuces, courgettes (and their flowers), rocket, runner beans, beetroots and herbs, picked apples from old, lichen-covered trees in the orchard, and gathered blackberries from the hedgerows up the hills. Dinner was frittered courgette flowers followed by beetroot salad with crumbled Devon Blue cheese and toasted pine nuts; wild sea bass from Hatherleigh market, stuffed with fennel and roasted; sliced potatoes baked with cream, onion, sage and a local cheese called Vintage Oke; radish salad; blanched radish tops in a Sichuanese ginger sauce (guess who made that dish); and blackberry and apple crumble with clotted cream. On other evenings we had teriyaki chicken with a rice salad jewelled with herbs, nuts and dried fruit, ribbony cucumber salad, rhubarb fool with ginger biscuits; a tapas menu of meatballs in tomato sauce, patatas bravas, chicken with chorizo, kidney bean stew; home-made quiches; wine-poached pears with blackberry sauce; and so on.

It wasn’t as if we were having light lunches: every day, a visiting chef covered an old wooden table in salads, crab tarts, roasted aubergines, home-made soups, cold meats and cheeses, vegetables from the garden… Someone else kept delivering enormous trays of home-made cake (the sticky date cake, like sticky toffee pud without the sauce, was was the most scrumptious cake I’ve tasted in a long time). There were bacon and eggs and cereals for breakfast, scones with jam and clotted cream from time to time… And in case anyone was hungry between the four daily meals, we were allowed to help ourselves to food from the fridge, more cake, or biscuits from the biscuit tin whenever we pleased.

Of course, we were working intensely between meals, with discussions, readings, a field trip, critical analysis of texts, lectures and tutorials. While I’m not sure even I can argue that this is the kind of gruelling physical work that demands bacon sandwiches, potatoes dauphinoise and cake at two-hour intervals, it’s been delightful. But how am I going to cope without cooked breakfasts and cream teas every day now that I’m back home?

August 22, 2013

Stone Age cookery

I’m fascinated by news of some research that suggests Europeans were spicing their food with garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) in the Stone Age – there’s more about it here. Scientists at York University have analysed residues in fragments of clay cooking pots found at archaeological sites in Denmark and Germany, and discovered traces of the seeds of this plant. Because the mustard seeds have little nutritional value, the researchers reckon they must have been used to add flavour to the food. According to the BBC report on the story, “The implications from these findings challenge the previously held belief that hunter-gatherers were simply concerned with searching for calorific food”.

Somehow it surprises me that anyone should be surprised that our Stone Age ancestors were concerned with making their food more delicious. Isn’t taking pleasure in food part of what makes us human?

(Are there any other species that add relishes to their food as we do?)

August 21, 2013

The MSG controversy

This article ‘Breaking Bland’, by John Mahoney, is the most lucid, informative and interesting I’ve read on the whole MSG controversy. It goes into great detail about what exactly MSG is, how it is made, and how the human body interacts with glutamates.

This article ‘Breaking Bland’, by John Mahoney, is the most lucid, informative and interesting I’ve read on the whole MSG controversy. It goes into great detail about what exactly MSG is, how it is made, and how the human body interacts with glutamates.

It’s quite magnificently ironic that just as chefs at the cutting edge of Western gastronomy are becoming fascinated by MSG and umami, the Chinese are waking up to the stigma that has been attached to it for forty years and losing their taste for it, if this article in the Economic Observer, ‘China loses its taste for MSG’, is to be believed!

Even if Chinese people do request their food ‘without MSG’, it’s amazing how many chefs will continue to use so-called ‘chicken essence’ (ji jing 鸡精) anyway – and the cheap commercial ‘chicken essence’, which gives so many Chinese soups that intense umami taste and lurid yellow colour, has as its major ingredient MSG!

August 14, 2013

The ‘preserved mustard index’ 榨菜指标

Who would have guessed that a famous Chongqing pickle, the preserved mustard tuber made in the town of Fuling, would be used by the Chinese government to measure labour migration?! According to this article on the Xinhua news agency website (which I found via the South China Morning Post), zhacai 榨菜 is a ‘low quality consumable’ 低质易耗品 that people eat regardless their income. Under normal circumstances, the article says, consumption of zhacai, and instant noodles, is pretty much constant among the urban population – so if statisticians notice a sudden rise in zhacai sales in a particular city, this implies that a lot more people are now living there.

Who would have guessed that a famous Chongqing pickle, the preserved mustard tuber made in the town of Fuling, would be used by the Chinese government to measure labour migration?! According to this article on the Xinhua news agency website (which I found via the South China Morning Post), zhacai 榨菜 is a ‘low quality consumable’ 低质易耗品 that people eat regardless their income. Under normal circumstances, the article says, consumption of zhacai, and instant noodles, is pretty much constant among the urban population – so if statisticians notice a sudden rise in zhacai sales in a particular city, this implies that a lot more people are now living there.

For example, the Chinese National Reform and Development Commission found that the market share of Fuling zhacai sold in southern China slumped dramatically from 2007-2011, showing that some of the great tide of migrant workers who flocked there in the early days of reform had started to leave. Meanwhile, zhacai sales in Northern, Central and Northwestern China shot up, implying that these workers were returning home to the inland provinces. Obviously this ‘mustard index’ has huge implications for provincial governments trying to work out their expenditure on healthcare, education and so on. Fascinating!

So what is zhacai, and why is it such an essential, everyday food? Zhacai, or ‘pressed vegetable’, is made from the knobbly, swollen stem of a type of mustard green. The stems are shorn of any tough skin and air-dried until they soften. They are then salted for a few days, rinsed, pressed and finally packed into jars with ground chilli and other spices and left to mature for several months. Zhacai is made in many places and to many different recipes, but the most famous comes from Fuling, the town near the Yangtze River that was put on the international map as the setting for Peter Hessler’s superb River Town.

So what is zhacai, and why is it such an essential, everyday food? Zhacai, or ‘pressed vegetable’, is made from the knobbly, swollen stem of a type of mustard green. The stems are shorn of any tough skin and air-dried until they soften. They are then salted for a few days, rinsed, pressed and finally packed into jars with ground chilli and other spices and left to mature for several months. Zhacai is made in many places and to many different recipes, but the most famous comes from Fuling, the town near the Yangtze River that was put on the international map as the setting for Peter Hessler’s superb River Town.

No one could pretend that zhacai is the prettiest vegetable, but it’s extremely delicious: crisp and tender at the same time, sour, spicy and umami. You will often find it sold in tins in Chinese shops, usually labelled as ‘Sichuan preserved vegetable’. It may be available in knobbly chunks (like the picture top right), or ready-shredded. The small sachets pictured on the left are handy for long train journeys and quick meals. Zhacai has many culinary uses. It may be simply eaten as a relish with rice, breakfast rice gruel or a steamed bun. Otherwise, it can be sliced or slivered and stir-fried with pork (scrumptious), used to give an elegant salt-sourness to a light broth, or chopped up and scattered over silken tofu.

The silken tofu is a famous Chengdu street snack – you’ll find a version of the recipe in my Every Grain of Rice. Sichuan Cookery/Land of Plenty includes some other zhacai recipes.

July 20, 2013

Chinese vegetables grown in Kent

You can read my piece about Farmer Mau Chiping in today’s Financial Times magazine. For years I’ve been torn between my desires to buy as much local produce as possible and to cook as much Chinese food as possible. With meat and poultry, it’s fairly easy – try red-braising pork from the Ginger Pig! But the supply of locally grown Chinese vegetables has always been limited. That’s why I was so thrilled to discover the tiny shop just opposite Pang’s Printing Press, in an alley off Macclesfield Street in London’s Chinatown. It’s a small Chinese provisioners, selling basic seasonings, noodles and so on, but also vegetables from Mau Chiping’s farm in Kent. The choy sum and gai lan are glorious, as are the mustard greens, pak choy, water spinach and occasional treats such as stem lettuce (celtuce) and Chinese garlic chives. The farm is not certified organic, but mainly

You can read my piece about Farmer Mau Chiping in today’s Financial Times magazine. For years I’ve been torn between my desires to buy as much local produce as possible and to cook as much Chinese food as possible. With meat and poultry, it’s fairly easy – try red-braising pork from the Ginger Pig! But the supply of locally grown Chinese vegetables has always been limited. That’s why I was so thrilled to discover the tiny shop just opposite Pang’s Printing Press, in an alley off Macclesfield Street in London’s Chinatown. It’s a small Chinese provisioners, selling basic seasonings, noodles and so on, but also vegetables from Mau Chiping’s farm in Kent. The choy sum and gai lan are glorious, as are the mustard greens, pak choy, water spinach and occasional treats such as stem lettuce (celtuce) and Chinese garlic chives. The farm is not certified organic, but mainly

Garland chrysanthemum 茼蒿

fertilised with chicken and horse manure, and Mau says he uses pesticides only in extremis (the weeds and wildflowers infiltrating his vegetable beds lend support to this assurance). Since I found this shop, I’ve been buying a large proportion of my everyday greens there.

Lunch at the Mau farmhouse

Mau Chiping, now in his seventies, grew up in a Hakka family in rural Guangdong Province, and won a coveted place at medical school in the provincial capital, Guangzhou. But although a promising career as a doctor might have beckoned, he was the grandson of a landlord, which made him a easy target for Maoist persecution. In 1959, the first year of China’s great famine, he secured permission to visit his father, who had already fled to Hong Kong. ‘My father wept at the thought that I might return to China after my stay,’ he says. ‘It was the only time I ever saw my father cry. I couldn’t leave him.’ So Mau stayed in Hong Kong, working as a vet until he obtained a work permit for Britain in 1974. After emigrating with his wife and four children, Mau worked in a Chinese restaurant while learning English in his spare time (he says he spent a quarter of his salary on English classes, and stayed up late after service to do his homework while his colleagues played mahjong). Eventually, in 1980, he bought two acres of farmland near Tonbridge with a bank loan, and learnet the basics of agriculture from another Chinese farmer. Originally, he and his wife owned the Chinatown shop, but these days they are just one of its suppliers.

Please be aware that the shop also stocks some imported Chinese vegetables. The imported vegetables are normally displayed in polystyrene boxes, while the Kent produce is displayed in wooden pallets at the back.

Fuchsia Dunlop's Blog

- Fuchsia Dunlop's profile

- 392 followers