Fuchsia Dunlop's Blog, page 6

July 10, 2013

El Bulli: Ferran Adria and the art of food

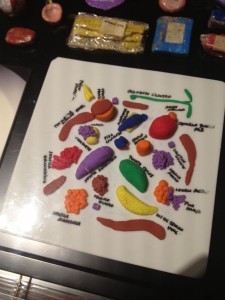

Last week I went to the opening of this new exhibition at Somerset House. It’s a peculiar idea, an exhibition about a restaurant without anything to taste, and I have to admit I was sceptical. So what’s in the exhibition? Well, there is a lot of memorabilia: old photographs, menus and the like. But what I found more interesting were the explorations of the creative process at El Bulli: a display of multicoloured modelling clays that were used to make maquettes for every dish, so that the proportions of each ingredient, each colour, each texture, could be reproduced accurately in the restaurant; the display of custom-made serving vessels, including strange bits of mesh, and indented glass. And there were many small video screens showing films of the construction of El Bulli dishes, which were compelling. The exhibition certainly helps to stake Ferran Adria’s claim to be considered as a creative artist and not a mere cook – but it’s hard to convey s sense the magic and fun of El Bulli in a museum in London…

Last week I went to the opening of this new exhibition at Somerset House. It’s a peculiar idea, an exhibition about a restaurant without anything to taste, and I have to admit I was sceptical. So what’s in the exhibition? Well, there is a lot of memorabilia: old photographs, menus and the like. But what I found more interesting were the explorations of the creative process at El Bulli: a display of multicoloured modelling clays that were used to make maquettes for every dish, so that the proportions of each ingredient, each colour, each texture, could be reproduced accurately in the restaurant; the display of custom-made serving vessels, including strange bits of mesh, and indented glass. And there were many small video screens showing films of the construction of El Bulli dishes, which were compelling. The exhibition certainly helps to stake Ferran Adria’s claim to be considered as a creative artist and not a mere cook – but it’s hard to convey s sense the magic and fun of El Bulli in a museum in London…

Maquette for a dish

One interesting moment: I was looking at a backlit display of thumbnail photographs of every dish created at El Bulli – an impressive tapestry of images, when I got chatting to a well-known British chef who had had a few glasses of wine. ‘I think it looks like an abortion!’ she told me. ‘Why?’ I asked. She said (as closely as I can remember): ‘This isn’t food. It’s got nothing to do with food, with the earth, with Spain, with what his grandmothers cooked. Ferran Adria has fucked it all up. Because now young people don’t want to learn how to cook, they want to learn to be like him. And he may do what he does brilliantly, but few others can. He’s fucked it all up.’

I have to say that I disagree with a lot of what she said. A fairly large part of Ferran Adria’s oeuvre is rooted in Catalonia – for example, his spherified olives and deconstructed constructed croquettes. But even if much of his cooking was wild and inventive, it doesn’t have to be an alternative to our grandmothers’ cooking. It’s an exploration of food and culinary culture, a game, an explosion of creativity, something marvellous and incredible – but no one in their right mind would want to eat his food every day. Real, earthy home cooking and Adria’s culinary pyrotechnics can coexist in a lively food culture.

On the other hand, I’ve heard from friends in Barcelona that El Bulli has had a castastrophic effect on the younger generation of chefs, as this lady argued. Everyone, they say, wants to be a gastro-magician, a celebrity, a superstar. They want to invent and play – but they no longer want to learn the basic skills of Catalan cuisine.

Eating kangaroo – reprise

My piece on the Australian relationship with eating kangaroo meat seems to have stirred up a lot of interest and emotion! It was one of the most read and shared articles on the BBC news website throughout the day it was published, and I received a fair number of tweets, emails and comments about it, roughly divided between people who agreed with what I said and those who didn’t.

On Twitter, @RestaurantsRant said: ‘I think Australians, in general, are pretty unadventurous’. According to @QuarryHillWines, ‘That was a good piece. It’s a fine meat to cook with. Takes to cumin, coriander seed, star anise, ras el hanout… versatile’. @Bruce_Palling asked if it was ‘frying the flag’, while @Cam_Mck suggested my article was an example of ‘how to: 1. Ignore the richness of our food culture. 2. Write about our ignorance. 3. ??? 4. Profit’ (I have to say, given the fees paid by the BBC, I had to laugh at his suggestion that I was profiting by writing the piece!)

Anyway, the issue is clearly quite complicated, and here’s some further food for thought: according to the abovementioned @Cam_Mck, you can read the ‘real facts’ about kangaroo meat here.

And Dr Gerard Bodeker, of the Division of Medical Sciences at University of Oxford (and also Adjunct Professor of Epidemiology and Columbia University, New York) sent me a very interesting email which I reproduce here with his permission:

In response to Fuchsia Dunlop’s online BBC News Magazine article ‘Eating Skippy: Why Australia has a problem with kangaroo meat’, it would be important to add that there are many real health concerns about eating kangaroo meat that lend support to the cultural aversion aversion to ‘eating Skippy’.

A BBC report in April 2013 cited a study in Nature on the dangers of L-carnitin in red meat. The study found that when L-carnitin is metabolised by gut bacteria, it turns into a compound which damages arteries supplying blood to the heart and to the brain: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-23...

It turns out that kangaroo meat has more L-carnitin per gram than any other red meat. In view of this, there is now a re-think in Australia about favouring kangaroo meat as a ‘healthy’ red meat.

There are other health reasons as well for a re-think on kangaroo meat.

Two serious infectious diseases are known to be transmitted via kangaroo meat. Toxoplasmosis and the bacterial disease, Salmonellosis are directly related to the handling, processing and consumption of kangaroo meat. Chefs recommending rare & raw treatments of kangaroo meat run the risk of exposing the public to acute health conditions.

Indeed, Russia, cited in your article as a major market for kangaroo meat, banned kangaroo meat exports from Australia in 2009 after finding high levels of bacterial contamination.

Supporting the national aversion to ‘eating Skippy’, there are also animal welfare issues in the kangaroo meat industry, including reportedly inhumane killing methods and cruel killing of baby kangaroos:

While ‘Eating Skippy’ may be a cultural reflex that prevents many Australians from eating their national animal – against the advice of some nutritionists – that sentiment may be protecting them from very real dangers of a so-called ‘healthy red meat’ and the ethics of its supply chain.

As I replied to him, I was under the impression that the Russian export ban was a response to a campaign by animal rights activists on cruelty grounds (and was revoked when the kangaroo meat industry agreed to slaughter only males); I hadn’t heard of these health considerations.

And I’d also be interested to know about the scale of difference in the relative health risks of kangaroo and other red meats, and whether the infections he mentions are peculiar to kangaroo, or found in other wild game (it’s worth remembering the salmonella risk of eating chicken, and the risks of eating uncooked pork).

June 30, 2013

Eating your national emblem

You can read my piece about the Australian hang-up about eating kangaroo meat here, on the BBC website. And if you like, listen to a different version on From Our Own Correspondent here – it’s the last recording, towards the end of the programme.

You can read my piece about the Australian hang-up about eating kangaroo meat here, on the BBC website. And if you like, listen to a different version on From Our Own Correspondent here – it’s the last recording, towards the end of the programme.

Of course, Australian’s reluctance to eat their most distinctive local meat is not particularly surprising, given the deep irrationality of human food choices. Most people in the West, for example, will eat shrimps but not insects, pork but not dog, and beef but not horse meat. History is littered with examples of societies that suffered because they wouldn’t change their eating habits, like the mediaeval Norse community on Greenland, who starved to death because they refused to eat fish and seal like the natives, but insisted on maintaining a tradition of cattle farming that was unsuited to their fragile northern habitat.

their eating habits, like the mediaeval Norse community on Greenland, who starved to death because they refused to eat fish and seal like the natives, but insisted on maintaining a tradition of cattle farming that was unsuited to their fragile northern habitat.

Kangaroo meat shop in Adelaide

The interesting question is how much people will be prepared to change their eating habits to accommodate climate change and rising global population. If the UN has its way, we’ll soon by eating insects...

Above, on the right, by the way, you can see my own cooking experiments: Sichuanese kangaroo tail soup; stir-fried wallaby with yellow chives; wallaby with cumin; and mapo tofu with minced wallaby.

June 24, 2013

The pleasures of texture

This is a video of a magnificent dried sea cucumber after two days of soaking and slow-cooking. As you can see, it has a lazy, springy, sticky texture. When I brought it home, dry and rock-hard like a fossil, it had an unpleasant fishy taste (like Bombay Duck, if anyone can remember that). But after the requisite soaking and simmering, it had virtually no aroma or flavour: it had been reduced to pure, glorious texture – which meant it was ready to be cooked. Isn’t it amazing?

One of the great barriers to outsiders’ appreciation of Chinese food is the Chinese love of textures that others consider revolting, as I’ve written before: the slimy, slithery, bouncy and rubbery; the wet crispness of gristle; the brisk snappiness of goose intestines; the sticky voluptuousness of that reconstituted dried sea cucucmber. This was the subject of a talk I gave as part of a London Gastronomy Seminar last week, following an excellent exposition by French psychologist Dominique Valentin on the cultural influence on food choices.

We ended the evening with a tutored tasting of some classic ‘texture foods’ (pictured right): naked, undressed jellyfish in all its crisp slitheriness, a terrine of pressed pig’s ear, layered with thin sheets of crunchy cartilage; sticky ox tendons in a spicy sauce; and then, for each guest, a duck’s tongue, which is a perfect example of a Chinese delicacy with a ‘high grapple factor’, which is to say one that requires a detailed, concentrated engagement of tongue and teeth to separate out the bouncy flesh and slender spikes of cartilage. We also had a comparative tasting of fermented tofu and Stilton, to highlight the distinction made by some Chinese friends of mine between what they found the clean, rapidly-dispersing stinkiness of fermented tofu, and the greasy, clingy, mouth-coating stinkiness of cheese.

We ended the evening with a tutored tasting of some classic ‘texture foods’ (pictured right): naked, undressed jellyfish in all its crisp slitheriness, a terrine of pressed pig’s ear, layered with thin sheets of crunchy cartilage; sticky ox tendons in a spicy sauce; and then, for each guest, a duck’s tongue, which is a perfect example of a Chinese delicacy with a ‘high grapple factor’, which is to say one that requires a detailed, concentrated engagement of tongue and teeth to separate out the bouncy flesh and slender spikes of cartilage. We also had a comparative tasting of fermented tofu and Stilton, to highlight the distinction made by some Chinese friends of mine between what they found the clean, rapidly-dispersing stinkiness of fermented tofu, and the greasy, clingy, mouth-coating stinkiness of cheese.

It gave me great pleasure to see a whole roomful of people eating (in most cases) their first duck tongue, in the intentional pursuit of pleasure. (I’ve received quite a number of emails from readers of my book ‘Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper’ who say that they’ve tried eating ‘rubbery things’ with a completely different, open-minded attitude after reading the chapter ‘The Rubber Factor’, which attempts to explain why the Chinese enjoy eating flavourless foods with interesting textures.)

May 13, 2013

Chinese reflections on British life

Over dinner with some Sichuanese chef and restaurateur friends in London, this is what I was told: “The other day a Romanian woman came into my restaurant alone, and ordered several dishes. When she had eaten half the food, she called me over, and complained that one of the dishes was too sweet, and one too salty. Politely, I invited her to have a couple of other dishes to replace them, and sent out two more, complimentary dishes. Then she asked for the bill, and said it was too expensive, and she couldn’t afford it. I pointed out that all the prices were listed clearly on the menu, and she still said she couldn’t pay. Eventually I told her I would call the police – and I did. But when the police came they said there was nothing they could do, even though they agreed she had probably done the same thing at countless other restaurants. So they left, and the woman got away with her free meal.” [NB this is a fine example of the practice known as bawangcan 霸王餐, tyrannical eating, which you can read a little more about here]

The restaurateur, who has been in London for more than a decade, was shocked and amazed by this turn of events. “I really like English culture, and I do think English people deserve the word ‘gentlemen’,” he said, “But you really take human rights too far here. The government needs to be more strict, and less easy about handing out British citizenship and welfare and so on. If you are too soft, you’ll end up like the United States, with everyone carrying guns. People are too lazy here, too, and because of the prevalence of supermarkets and fast-food joints, they are forgetting how to cook. Honestly, I think Great Britain was Great a hundred or two hundred years ago [NB this is exactly when Britain was abusing China in the most ungentlemanly manner], but these days it’s just ‘Britain’”.

Interesting to hear a Chinese immigrant complaining about excessive human rights, and praising colonial-era Britain… and I appreciate that he thought the loss of cooking skills was one of the major causes of the decline of a once-Great country…

May 10, 2013

Just back from New York!

I spent a few days in New York for the James Beard Foundation Awards – a wonderful trip, as you can see from the photo! (Here‘s a link to the relevant article in Lucky Peach.) It was fantastic to run into so many good friends, and the weather was New York at its shining, brilliant best.

I spent a few days in New York for the James Beard Foundation Awards – a wonderful trip, as you can see from the photo! (Here‘s a link to the relevant article in Lucky Peach.) It was fantastic to run into so many good friends, and the weather was New York at its shining, brilliant best.

The most beautiful building, glimpsed through Gramercy Park

Foodwise: delicious crisp tofu and bulgogi beef sliders at a newish Korean place, Danji; an utterly perfect, simple lunch at the Gramercy Tavern; and a lavish, dreamlike brunch for Daniel Boulud’s 20th New York anniversary. Oh, and I cooked a Sichuanese feast for the friends who put me up, with fresh produce from Chinatown. (And apart from the food, it would almost be worth going to New York

just to have another look at the portrait of Sir Thomas More by Hans Holbein in the Frick Collection.)

April 18, 2013

Swords into ploughshares (and vice versa)

With all the horror of the Boston bombings, and of the way whoever did it turned a useful cooking pot (the pressure cooker) into a murderous weapon, I thought I’d mention something altogether opposite, and that is the remarkable knives made on the Taiwanese islands of Kinmen.

With all the horror of the Boston bombings, and of the way whoever did it turned a useful cooking pot (the pressure cooker) into a murderous weapon, I thought I’d mention something altogether opposite, and that is the remarkable knives made on the Taiwanese islands of Kinmen.

The Kinmen (also known as Jinmen and Quemoy) islands lie barely a couple of kilometres off the coast of Fujian Province, but have been under Taiwanese administration since the end of the Chinese civil war. In the 1950s, during the First and Second Taiwan Strait Crises, they were bombarded by Mainland forces, and the islands were littered with hundreds of thousands of artillery shells. Local artisans gathered up the shells, and transformed them into knives, which have become a famous local product.

This is one of the Kinmen knives I bought in Taipei last May. It’s a lovely knife, pleasingly weighted, and the shopkeeper who sold it to me said that the military-grade steel makes it particularly durable. Bombs into kitchen knives; destruction into creativity, nourishment, life and pleasure.

April 14, 2013

Why do Americans think ice is so nice?

Ice blocks, Kashgar Sunday market

The first time I went to America, I couldn’t understand why, whenever I checked into a hotel, the first thing the bell boy told me was where I could find ice. He might point out an ice dispenser in the lift lobby, or tell me which number I could call to have some ice sent over. Ice, it seemed, was the number-one preoccupation of American hotel guests, whatever the season. As a Chinese convert, though, the first thing I want to see when I check into a hotel room is hot water and the means to make tea. In the old days in China, every hotel or guesthouse would provide tealeaves and lidded mugs, and a fuwuyuan would bring you a thermos filled with hot water as soon as you arrived – one of those lovely, old-fashioned thermoses with floral patterns that evoke the style of pre-war Shanghai. Fresh supplies of hot water could be obtained from a service room on every floor where a giant steel samovar simmered away, day and night. These days, you’re more likely to be faced with an electric kettle, but the tea-making facilities are non-negotiable. A cup of tea always has to be part of the welcome, whether you are arriving at someone’s home or office, or checking into a hotel.

So hotel rooms in America always feel strangely ill-equipped. If you’re lucky, you might find a coffee maker which you can just about use to boil water for tea, but this seems to be the exception. If you call room service for boiling water, it will have cooled down too much by the time it arrives to make a decent brew, and you may be faced with a hefty charge. On my recent trip to America, I travelled as usual with a tin of my favourite tea leaves, but was unable to use them at all. And I just can’t understand why anyone would come in from the bitter cold of a New York winter and want to drink a glass of water packed with ice! But people in the States seem to be addicted to it. One British friend of mine who has settled there can barely drink anything without ice; I noticed people on planes ordering iced drinks with an extra cup of neat ice on the side, just in case; waiters were barely unable to process my outlandish request for water without ice. And when I requested hot water – I had a bad cold, I’m used to drinking ‘white boiled water’ (bai kaishui 白开水)in China, and the thought of consuming ice was unbearable – they clearly thought I was insane.

In China, cold drinks, especially in midwinter, are regarded as a bad idea. My Chinese doctor elaborated: “Iced drinks slow down the movement of your qi. Normally we say that your skin protects you from the onslaught of external cold. Drinking iced drinks is like allowing spies to infiltrate your body.”

April 4, 2013

In praise of simplicity

The picture on the left is of my lunch yesterday, at home: pao fan 泡饭 (‘soaked’ or soupy rice) made from leftovers of brown rice with broccoli, with added green pak choy, and some spicy fermented tofu. You could say it was the most basic, skeletal epitome of the Chinese meal: a staple grain, some healthy brassica greens, a little protein (the tofu), and a strongly-flavoured relish to ‘send the rice down’ (xia fan 下饭) (in this case the tofu again). It was just what I felt like after a few days of rather gluttonous eating over Easter: plain, cheap, healthy and nutritious but also rather nice.

The picture on the left is of my lunch yesterday, at home: pao fan 泡饭 (‘soaked’ or soupy rice) made from leftovers of brown rice with broccoli, with added green pak choy, and some spicy fermented tofu. You could say it was the most basic, skeletal epitome of the Chinese meal: a staple grain, some healthy brassica greens, a little protein (the tofu), and a strongly-flavoured relish to ‘send the rice down’ (xia fan 下饭) (in this case the tofu again). It was just what I felt like after a few days of rather gluttonous eating over Easter: plain, cheap, healthy and nutritious but also rather nice.

The privileged among us really do live in one of the golden ages of eating. Like rich Romans of classical times, who served peacocks at their banquets, or the upper classes of Tang Dynasty Chang’an, with their predilection for Silk Road spices, we can pick and choose what we consume; we can have Sichuanese food tonight, Italian tomorrow and Japanese the day after; we can buy fresh uni, fennel pollen and verjuice; we can eat meat at every meal, or decide to become vegetarian for intellectual reasons. We can fuss over the provenance and purity of our coffee and chocolate. We can throw away vegetables that are a little wilted, or good food that we simply forgot to cook because we were out at some fancy new restaurant. Our biscuits are double-choc or triple-choc, our ice creams are threaded with extra nuggets of luxury. The world is our oyster.

Eggs, cabbage, mushrooms

Such decadence is always a privilege, and more precarious than it might seem. It’s impossible not to think of this in the midst of a raging recession, and, even more seriously, a period of mass extinctions and unstable weather. And that is perhaps why, lucky as I feel to be part of the British Established Middle Class (according to the new survey!) in this era of rich and varied eating, and satisfied as I am with the kou fu that comes with my job (kou fu 口福is a wonderful Chinese phrase that means ‘the good fortune to happen upon delicious food’), I try not to forget that eating well is a privilege, and that rice, cabbage and tofu is enough for an everyday lunch.

Potato, cabbage, broccoli, sardines

Of course the great thing about Chinese cooking is that modest, cheap meals can be so extremely delicious and satisfying. I’m a great fan of fermented tofu, which has such an electrifying flavour that it really can enliven the taste of a bowlful of plain rice and vegetables (lao gan ma 老干妈 chilli and black bean sauce and gan lan cai 橄榄菜 ‘olive vegetable’ are two other scrumptious relishes). Some pickled vegetables, a spoonful of dried shrimps (see my last blog post), a few chillies, or a single slice of streaky bacon – all these can make the plainest, cheapest foods taste amazing. And rather than meat, why not have with your rice or noodles a single egg, fried both sides and finished with a streak of soy sauce?

Fruit leather rabbit

Simnel cake

Above you’ll also find a couple of other pictures of simple lunches I’ve had in the last week or so. Both meals took about half an hour to prepare. On the upper right you can see some stir-fried spring greens with dried shrimp, with steamed eggs and stir-fried mushrooms – I cooked the mushrooms in a little duck fat I had in the fridge, with garlic and spring onions. I was pleased because a (Taiwanese) friend who had come over to fix my kitchen door, and who had politely declined an offer of lunch, was simply unable to resist the cooking smells and ended up sharing everything with me, very happily. And on the left is a meal I rustled up on a day when there didn’t seem to be any food in the house: the end of the spring cabbage I cooked for the first meal, again with a few dried shrimps, one tiny leftover head of broccoli (including the stalks, peeled and sliced) with ginger and garlic; two potatoes slivered and stir-fried with chilli and Sichuan pepper; and then a tin of sardines because I was particularly hungry! I make no apologies for the careless presentation of the dishes in the pic on the left, but this was a quick fix on a busy day, and I wanted to show it exactly as it was – basic, but delicious.

And there’s also a pic of some of the Easter feasting – namely my first Simnel cake (!), and an Easter rabbit I cut out of Iranian fruit leather at my small niece’s request (she’s obsessed with rabbits).

March 25, 2013

Magic ingredients: Papery dried shrimp 虾皮

I always keep a bagful of these tiny dried shrimp, known as ‘shrimp skin’ in Chinese, in my freezer. A spoonful or two can be used to jazz up a bowlful of wontons in soup, fried rice or an omelette, and a handful transforms a cabbage into a fragrant, irresistible stir-fry. They are made from tiny, unshelled shrimps that are boiled and then sun-dried or baked dry over a gentle heat. As you might guest, they have a salty, umami taste that can lift the flavour of all kinds of savoury dishes. (Some people find their taste a bit strong and fishy, but not many, in my experience.)

I always keep a bagful of these tiny dried shrimp, known as ‘shrimp skin’ in Chinese, in my freezer. A spoonful or two can be used to jazz up a bowlful of wontons in soup, fried rice or an omelette, and a handful transforms a cabbage into a fragrant, irresistible stir-fry. They are made from tiny, unshelled shrimps that are boiled and then sun-dried or baked dry over a gentle heat. As you might guest, they have a salty, umami taste that can lift the flavour of all kinds of savoury dishes. (Some people find their taste a bit strong and fishy, but not many, in my experience.)

I’ve included a couple of peppercorns in the photograph on the right so you can see how extremely small they are.

Recipe ideas:

1. Stir them into beaten egg, with some finely sliced spring onions, white pepper and salt if you need it, and make an omelette: I do this in a wok, scrambling the egg in the base of the wok until it’s nearly cooked, and then leaving it to turn golden on the base before flipping it over to fry the other side.

1. Stir them into beaten egg, with some finely sliced spring onions, white pepper and salt if you need it, and make an omelette: I do this in a wok, scrambling the egg in the base of the wok until it’s nearly cooked, and then leaving it to turn golden on the base before flipping it over to fry the other side.

2. Use them to add a bit of extra excitement to fried rice. This morning I used up some leftover rice as

Fried rice

follows: Break up the rice so it doesn’t stick together in large clumps; Heat a little oil in a seasoned wok, add a spoonful or two of papery dried shrimp and fry gently until they smell amazing and are faintly golden. Add some beaten egg. When the egg is half-cooked, tip in the cold, cooked rice and stir-fry over a high heat until it is piping hot and fragrant, and making popping noises against the side of the wok. Season with salt or light soy sauce to taste. Add finely sliced spring onion greens and continue to stir until you can smell them. Stir in a tiny amount of sesame oil if you please, to enhance the aroma, and then serve. This would be even more delicious with brown rice, in my opinion.

3. Add papery dried shrimp, dried laver seaweed (紫菜) and finely sliced spring onion greens to the clear stock in which you serve wontons or boiled jiaozi dumplings (full recipe in my book Every Grain of Rice).

4. Fry generous amounts of the shrimps in hot oil until crisp and fragrant; set aside. Add a little more oil to your wok, add very finely sliced spring greens, Savoy cabbage or other greens and stir-fry until barely cooked. Add the fried shrimps, with salt and soy sauce to taste, and finally spring onions (full recipe in Every Grain of Rice). This is possibly my favourite way to eat cabbage.

The shrimp are so thin that they can be used directly from frozen, and they keep for ages in the freezer. An indispensable stand-by ingredient.

Fuchsia Dunlop's Blog

- Fuchsia Dunlop's profile

- 392 followers