Joshua Corey's Blog, page 15

January 30, 2019

100 Words: ROMA (2018), directed by Alfonso Cuarón

We begin with an opaque gray surface gone translucent with water, slicking a new pane of vision onto the parking slabs, through which we get a glimpse of the black-and-white sky with a jet streaming across it. We end with the almost-silent heroine climbing an exterior set of stairs up into that same sky, with likely the same jet marking the limits of the quasi-Proustian transcendence Cuarón imposes on this fantasia of his 1970s childhood in Mexico City, a politically vapid elegy for the lost kingship of the middle class. Only our heroine’s face, indigenous and all-absorptive, is no replica.

November 26, 2018

Unattempted essay: "The Earthly Condition"

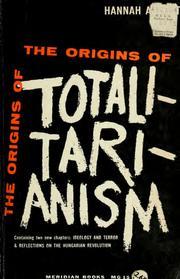

[These notes are circa 2014, the crucible of my Hannah Arendt book.]

Arendt as a means of inserting ethics into process ontology, or at least putting ethics into fruitful relation with same.

A renewed theory of the subject. Delusions of Greenness in the Avant-Garde: diminishing the subject is not the means to a green politics.

Forgiveness and the passage of love.

David Macaluey, ed. Minding Nature: The Philosophers of Ecology (Guilford Press, 1996), including his own essay, “Hannah Arendt and the Politics of Place: From Earth Alienation to Oikos” (pp. 102-133).

The earth vs. world distinction is from Heidegger, of course, and not original with Arendt; but where H. questions the authenticity of the modern world as it emerges from/enframes the earth, Arendt celebrates the public world and warns against its degradation without, so far as I can tell, much reference to the dangers presented to the world by the “conquest of nature”—a conquest that only fitfully enters politics and is much more the overwhelming program of “the social” and of capitalism.

Arendt in Macauley’s account a theorist of globalization (though he does not use this word) by which the world, in presenting itself for the first time as a totality (first through the discovery of America, later by discovery of the universe), causes distance to disappear. (What is far away appears closest to us in our media feeds, no? While our experience of “the local,” because unmediated, becomes wavery and insubstantial.)

One Arendtian insight that anticipates Latour, et al, is the political dimension of scientific organization—she points out that the Royal Society’s injunction not to take political stands may be the origin of the ethos of scientific objectivity, while at the same time noting that “where men organize they intend to act and to acquire power” (Human Condition 271 n. 26, my emphasis). “No scientific teamwork is pure science, whether its aim is to act upon society and secure its members a certain position within it or—as was and still is to a large extent the case of organized research in the natural sciences—to act together and in concert in order to conquer nature” (ibid, my emphasis). Interesting that there’s no distinction made here between political power and power over nature—both have their roots in our “age of organisation. Organised thought is the basis of organised action” (this is Arendt quoting Whitehead, The Aims of Education 106-7).

Acting into nature is Arendt’s phrase—and action is always political.

Scientific knowledge comes from action, not contemplation (Arendt 290); we intervene in nature rather than contemplate it. This of course harmonizes with the fundamental 20th century insight of Heisenberg/Bohr.

In footnote 8, Macauley notes that it is Descartes' “wandering (aberrare)” that “places him securely in the world,” as opposed to anchoring in the earthly (the cogito doubts the earth of the senses and places the thinker into the universe). This resonates with Whitehead’s affirmation that “Modern science has imposed on humanity the necessity for wandering… It is the business of the future to be dangerous” (SMW 207-8).

David Abram, “Merleau-Ponty and the Voice of the Earth,” also in Macauley. A crucial and interesting point from Macaluey’s fn. 10: “we live not on the earth as we are wont to think, but within it, since the earth includes the heavens (or sky and atmosphere) as well as the soil and the sea, a point brought out by the Gaia hypothesis and suggested in Merleau-Ponty’s later writings” (127). This is highly suggestive both in terms of climate disruption and Heidegger’s fourfold.

A cite of Arendt on the “alien” from Origins of Totalitarianism suggests a curious connection between otherness and necessity as that which human beings hate and fear: “the ‘alien’ is ‘a frightening symbol of the fact of difference as such, of individuality as such, and indicates those realms in which men cannot change and cannot act and in which, therefore, he has a distinct tendency to destroy’” (quoted in Macauley 107).

Alienation may be a bad thing, but is wandering? Is “rootedness” always to be valorized? We are dangerously close to Blut und Boden, no? Something in me always rises up in protest against this ecological argument. Part of me affirms science, affirms space travel, resists “the surly bonds of earth,” etc. Put another way, with Whitehead I wish to affirm adventure. (Another word for action in its inherent unpredictability.)

Macauley asserts that Arendt rejects Heidegger’s mythic earth in favor of earth as “planet,” and points out that the Greek planetes means “to wander” (108). The difficulty here is in recognizing the earth’s alienation without homogenizing it, “failing to provide an alternative conception which accounts for geographic difference and the uniqueness of living in particular places.” (Might this not be a task for poetry? It seems very difficult for philosophers such as Arendt and Whitehead not to homogenize and generalize—in fact, providing fresh generalizations is the entire point of philosophy, according to Whitehead.)

Misread “the infinitization of the universe” as “the infantalization of the universe.”

It’s hard to disagree with Macauley on, for example, the depredations of the automobile, but I dislike the Puritanical tone.

Macauley: “it is surprising how rarely she acknowledges her debt to” Heidegger (110). Not really: he is the philosophical planet whose gravity slingshots her onto her own political path.

Phenomenology and ecology—the combination gets mystical and “deep” pretty quickly. At this stage, I think the conflation of the two is ripe for critique. One of the reasons Arendt interests me is because she asserts the primacy of the world over the earth, while acknowledging the former’s dependence upon the latter. The argument to be extrapolated from Arendt, perhaps, is that the latter is now as dependent on the former—the earth can only be saved by the world, and by becoming part of the world, rather than functioning as the withdrawn ground of the world. This requires that the earth be represented in politics. I suppose I’m back to Latour and his “parliament of things.” (Arendt + Whitehead = Latour?)

Whitehead’s thought is not, after all, earth-bound, in spite of his instinctive sympathy for Wordsworth and Shelley. His ontology is just that: a universal theory of the universe.

Macauley is beginning to irritate me, but I can get on board with this: “Arendt is aware [of misuses of the term “natural”] and does not seek false homes, roots, or grounds, but attempts to think without the security of firm foundations” (116). Macauley mentions at the start of his essay but does not much mention Arendt’s own history as a displaced person and Jew here.

“Worldlessness” and “world alienation” are of course more central to Arendt’s thought than earth alienation, and much closer to her own historical experience.

Agriculture as “between earth and world,” the point of transition or metabolism “from the biological cycle to the human artifice” (116). But for Macauley it seems agriculture is a disaster and a violence.

Connection between what Arendt sees as the withdrawal of the stable and permanent human world and the Anthropocene, which puts the human/nonhuman boundary under erasure? The mutual absorption of technology and climate exposes us to the violence inherent in both.

Macaluey criticizes Arendt’s characterization of nature as the realm of necessity and her condoning artifice-as-violence against nature as the means of guaranteeing human freedom. He says she shows no sense of nature as free or spontaneous—“Contrary to Arendt’s claims, nature has been a source of freedom, value, and even objectivity” in the writing of Bookchin, Whitehead, and others (120). It’s true that Arendt’s thought wouldn’t seem to leave much of an opening for anarchism, which is the political movement most friendly to, and which imitates and participates, ecology.

Macauley: “The rift between necessity and freedom is of the same kind as the stultifying dualism which has been established between, for example, ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ and which has been challenged only rarely with depth and creativity by thinkers in the critical utopian tradition, such as Charles Fourier and Ernst Bloch” (120).

Arendt certainly makes no room for the freedom of the nonhuman or any sense of the nonhuman as a social actor (for sure) or a political actor (potentially). She has too much confidence in the “inexhaustible and indefatigable earth” to recognize that it needs a world, too.

One of Arendt’s broadest claims is that human freedom is always based on domination, either of a class of humans (slaves), or of nature; otherwise one is in the grip of “necessity” and lacks freedom. But is it correct to see ourselves as dominated by nature just because we are in mortal bodies? Macauley says we need to get beyond this dualistic thinking but doesn’t offer a clear direction how.

Arendt: “the world of machines has become a substitute for the real world,” a “pseudo world [that] cannot fulfill the most important task of the human artifice, which is to offer mortals a dwelling place more permanent and more stable than themselves” (152). This begs to be recast in the light of the Internet, which certainly casts an illusion of, if not stability and permanence, a kind of public life largely divorced from politics that can seem more “real” or more significant (as public) than an embodied life felt to be entirely privatized.

The “repetitiveness” of labor—well, what is our Net existence but laborious and repetitive? If one does not participate the “news feed,” one might as well not exist, publicly speaking.

A useful footnote of Macauley’s (75): “in contrast to earlier historical representations of nature, a postmodern view appears to conceive of nature in nonanalogical, informational terms” (italics original). Nature as data, DNA, etc.

Apparently there’s been some work using Arendt to read Gary Snyder.

Arendt would presumably object to ecology as an oikos-discourse—if it were another manifestation of the imperial “social,” an attack on the polis and public.

What to call those spaces in which both human-human and human-nonhuman contacts are frequent and facilitated? Macauley calls them “areas generally outside or between the oikos and the polis which are neither strictly public nor private, but which often ground, embed, or even enclose the agonistic and cooperative public spaces…. they are already complex and diverse locations which offer us more than ‘raw materials,’ ‘resources,’ or a res publica, even if they are by nature nonpolitical (though the disposition we have toward such places is often very political)” (125).

I’m not impressed with his trite dismissal of Arendt’s cosmopolitan values.

Arendt speaks of "the essential worldly futility of the life process" (131), meaning that labor/life cannot create a world, but also seeming to suggest that values cannot emerge from labor or life. Value is presumably connected to appearing (as in the value of the person) and requires a world in which to manifest itself--registering aesthetically.

Clearly, Arendt deplores utilitarianism and is nostalgic for a Greek ethic of excellence (arête) achieved through action.

"World" for Arendt seems to be the monkey wrench in process, halting or slowing the cycle of labor and consumption. I must see what Whitehead has to say about endurance and duration to see whether he agrees, or if for him world-building is part of the universal process but on the scale of human societies.

The world for Arendt is the shelter of life but is in essence its opposite: the world's "very permanence stands in direct contrast to life" (135).

The processual in Arendt appears in her commitment to the uncertainties of politics and also of thinking--a commitment to perplexity and a renunciation of the comforts of ideology.

Rob Halpern on Oppen. And Bob Baker.

Object Oriented OlsoN!

The tension between process ontology and ethics is mirrored by the tension between objectivist and symbolist poetics. The one bring us closer to the world, but at the expense of ethical stance and motive action. The other puts the human mind at the center and so suffers from a precipitous loss of reality.

My intuition that Blake's "Human Form Divine" and Arendt's freedom of "men" are not as anthropocentric as they appear, but are openings into a "human universe" whereby the nonhuman discloses itself as meaningful and "human.”

Arendt and Whitehead are united in their fundamental pluralism.

Put another way, the task is to recover worldliness (“the recovery of the public world”) through a poetics that reveals the complex interactions of human and earthly processes; a sense of freedom that is not opposed to necessity but collaborates with and modifies necessity.

Man needs humility, but much more than this he needs to act. Without supporting his action by delusion; he must act in full knowledge of the Copernican revolution (the ecological thought) which paradoxically, by decentering the human, makes the human more necessary than ever. To collaborate with the vitality of the nonhuman and to influence it in pluralistic directions (an “earth ethic,” to extend Aldo Leopold’s “land ethic”).

The margin of the margin. My interest in pastoral began with my fascination with the persistence of this marginal mode within the marginal art of poetry.

Centrality of Arendt in tension with the projectivist or objectivist relinquishing of the “Man of Power.” What is the politics of “achievement”? There’s a degree of Heidegger’s Gelassenheit here, and an ecological stance. But Arendt is certainly for pluralism in the political sphere, which might be viewed as a proto-political ecology.

Literary politics and public politics—Alcalay argues they are intermingled. The comportment of poets who choose to publish with small presses or who circulate letters rather than publish essays is in his view more meaningful and can have greater impact than those who work within existing outlets. His example: an essay on Israel that he could have published in the NY Times but instead sent as a letter to Creeley. (Where is that letter now? In from the warring factions maybe?)

History of the earth/human—>process—>becoming

April 26, 2018

Writing </i#x3E;

Without as yet actually occupying the point where Archimedes had wished to stand, we have found a way to act on the earth as though we disposed of terrestrial nature from outside, from the point of Einstein’s ‘observer freely poised in space.’

— Hannah Arendt, "The Conquest of Space" (1963)

How does a project begin? I've been going through old notebooks trying to catch the moment in which my fascination with the relationship between Nazi phenomenologist Martin Heidegger and Jewish political theorist Hannah Arendt caught fire and began generating the poems and narrative fragments that would eventually comprise Hannah and the Master, my next book of poetry, scheduled to be published by Ahsahta Press in the fall of 2019. The book is a kind of speculative Singspiel, an inside-out historical novel, a lyric assemblage lateral to the time I lived its writing and the time it tries to recover from the lives of some of the twentieth century's most charismatic messiahs manqué: Simone Weil, Walter Benjamin, Paul Celan, Gershom Scholem, and of course most importantly and crucially, Arendt herself.

I can trace the project's beginnings to the fall of 2011, when I spent the better part of a month living in Berlin, trying to finish my first novel while caught up emotionally in the historical whirlwind centering on that most fateful of cities. I had long been an avid reader of Arendt's work, and had passed through a period of near-obsession with Heidegger while in grad school. Now I found myself returning to them both, following in the footsteps of their macabre and tantalizing waltz through the twentieth century as philosopher and political thinker, metaphysician and refugee, Nazi and Jew.

The world grounds itself on the earth and the earth juts through the world.

— Martin Heidegger, "The Origin of the Work of Art"

Two years later, while studying with Jane Bennett at the School of Criticism and Theory, the intuition at the book's center took hold of me: we in the early 21st century are reliving the 1930s; that the lack of a meaningful response to climate change was akin to lack of meaningful resistance to the rise of Hitler; that the political climate of our time was likely to lead to new forms of fascism. And the idea that the agonistic love affair between Heidegger and Arendt was somehow paradigmatic of the struggle we face today to create a politics and poetics of "the world" as Arendt conceived it. To recover the realm of action in the face of an ever more tumultuous, dynamic, unconcealed, and ungrounding "earth."

The only writer of history with the gift of setting alight the sparks of hope in the past, is the one who is convinced of this: that not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

— Walter Benjamin, "Theses on the Philosophy of History"

My task is Benjaminian; Hannah and the Masters is like a little Arcades Project, but whereas Benjamin sought the destiny of the twentieth century in the tea leaves of nineteenth-century Paris, I seek a strategy for the twenty-first century in revisiting if not redeeming this twentieth-century love story. The book is a kind of chrestomathy, a bricolage of pieces that insist on their pieceness (pieces here and here and here), yet not entirely lacking in narrative. I take the risk of reading Arendt against the grain, finding the remnants of Romanticism in her thought, taking her Greeks as literally as Heidegger took his. I wanted to engage history as something living--fragments of narrative that transmit by means of their telling IT MIGHT HAVE BEEN OTHERWISE.

Arendt's thought has taken on new urgency and relevance since the election; The Origins of Totalitarianism climbed the bestseller lists of 2017. She was very far from being on the political right, but she didn't easily align with the Left of her time, either. But what drew me and still draws me to her work are her qualities as a writer: the elasticity and tensile strength of her sentences which have in themselves an unmistakably moral force.

Then of course there is the phrase that she made notorious in the subtitle of her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Which the daily degradation of our environment, and of the countless human beings sacrificed at the altar of things-as-they-are, reverses and reveals as: the evil of banality. As she so hauntingly put it in her direct address to Eichmann at the book's end, "What you meant to say was that where all, or almost all, are guilty, nobody is."

What follows are a series of notes and reconstructions of the substance of the book as it came together over the course of the last five years.

***

Jan. 18, 2013

The inability to believe in the reality of the world beyond us (which includes us) seems the great predicament of our age. As is the possibility that Marcella Durand raises so brilliantly: the wilderness, the image of nature red in tooth and claw, has been wholly internalized, anthropomorphized: we are the storm, global warming is us, we are the extreme weather we (and countless other species) suffer. Yet this strange identity seems to contain the seeds of its own alienation--consciousness of the conditions of the Anthropocene paradoxically increases the sense of helplessness. I am really struck right now by the childlike, fatalistic tone that has infected our politics on every level. We can't even seem to stop insane people from acquiring guns and shooting schoolchildren, so how can we take on global warming? Or is this pessimism really a backdoor assertion of our true desire--freedom--freedom to own guns, freedom to buy plastic, freedom to drive cars, freedom to import cheap goods from elsewhere at the cost of exploitation. One longs for an outside (Spicer's "practice of Outside"?). An ontological pastoral (the ontological is pastoral): spiritual refuge in the concept of something beyond the human, the World Without Us (and before us, and after us). The imagination of outside--the outside is the imagination. How can this become meaningful--how can the Outside, rediscovered, pressure a response from the inside? Break through to the cogito, break it open? Bust up the solitude in the skull, in the city, in the elevator, in the automobile? Breaking toward the real?

*

Feb. 22nd, 2013 (Berkeley)

The Shelleyan gap between the things we “know” and the things we’ve internalized (I.e., the age of the Earth).

*

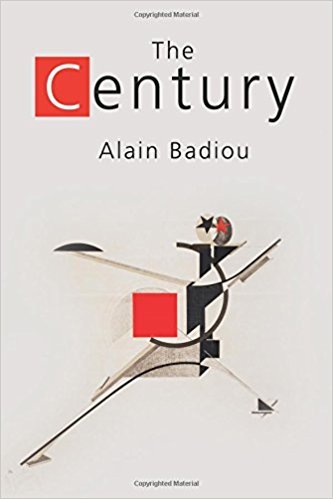

The writings of Alain Badiou have been a spur and an irritant to me since I first encountered them. The Century (2005) is a kind of historico-philosophical recovery project, in quite a different idiom than Benjamin's, which nevertheless seeks to recover the lost revolutionary potential of the twentieth century, defined for Badiou by its "passion for the real." The Century becomes one of the characters or gods of the book, appearing in two guises, "clockwise" and "counterclockwise." "Clockwise" narrates things as they happened; "counterclockwise" as they might have happened or as they reoccur, but in a new guise.

Clockwise: in the mid-1920s a very young Hannah Arendt becomes the student and then the lover of Martin Heidegger, her professor at the University of Marburg. After the war they re-establish their love, albeit on a largely one-sided and Platonic basis. Poetry intervenes at both moments: poems Arendt wrote as a very young woman, some of them touching on the affair with Heidegger; poems that Heidegger wrote for Arendt in the early 1950s.

Counterclockwise: my conception of Arendt and Heidegger as replicants, facsimiles of themselves, re-enacting their doomed and agonistic love in the 21st-century context of the WAVE, my figure for the oncoming trauma of climate change--or more precisely, the fascistic, exterministic politics likely to accompany or precede such change.

The poems are homophonic translations, countertranslations. By rendering the poetry of Arendt and Heidegger in a purely ear-English I open between the lines the calamitous gap between their styles of thought and their differing ethical failures.

"The poem is the thin blade between trace and completion" (Badiou 25).

*

May 14, 2013

What would a genuinely utopian work be, now? An elaborate Fourierist master plan? Or something fragmented yet corrosive of the limits the Spectacle has set on our imagination of what it is to live together?

Apparent inseparability of utopian and apocalyptic thought.

Marjorie Perloff finds few traces of Yiddish in Celan’s German.

Arendt-Heidegger. It’s possible I have only one subject as a fiction writer: the collision between masculine romanticism and feminist skepticism, or between the vision of personhood and actual persons.

I want a prose. Not a novel. Hannah and the Master. Allegorical love affair in the face of apocalypse. Short chapters. Collage. To write narrative as if it were poetry, poetry as if it were narrative.

[What follows this notebook entry are the poems or pieces that comprise the first section of the book, COUNTERCLOCKWISE \ THE WAVE.]

The Master is Celan's deathly Meister aus Deutschland; he is the pathetic lover-Master of Dickinson's letters who denies to her his vulnerability if not their shared humanity ("Have you the little chest—to put the alive—in?"); he is a manifestation of the Demiurge; he is Eldon Tyrell and Immortan Joe and every toxic patriarch who would subjugate and control life. He is Daddy and he will not do.

As for my Hannah, she both is and is not Hannah Arendt: she is the Master's creature, his beloved, his destroyer. In his thrall she is Hannah R., Hannah R(eplicant), who like Isaac Asimov's R. Daneel Olivaw must revise and reconstruct the code with which she's been programmed. Breaking free she is the one-armed warrior Hannah Furiosa, a manifestation of the rebellious Imperator Furiosa who is the secret hero of George Miller's 2015 film Mad Max: Fury Road, the title of which conceals her name in plain sight. The Zeroth Law of Hannah Furiosa is: Love the world. Love it ruined.

Return to the human citadel, reject the poisoned "green place." Reject the fantasy of the Archimedean "point in space." The world is what juts through.

*

May 2013

Eileen Myles: “Poems are not made out of words. They’re made out of emotional absences, rips and tears. That’s the incomplete true fabric of the text.

An Arendtian ecopolitics demands that we save the world, not the earth: If we focus on saving the earth we bring human freedom to an end. The world must not be reconfigured qua world-dependent-on-the-earth via political means.

We must extend personhood not to the nonhuman but to the extrahuman. How to make posterity a zone of living concern? Do we even care enough for our grandchildren? It is the next generation plus one that will find itself in extremis. [In the West. For the poorest in the Global South the calamity is here. The WAVE is indistinguishable from the human drive for development in the face of its manifest deadliness.]

Arendt distinguishes between the public and the political; only in the latter do people meet as peers, neither dominant nor dominated. There is pleasure for Arendt in political action, political appearing. Her elan, her joie de politique. Political eros.

Terror and despair of the local’s foreclosure by the global. Think global, don’t act at all.

May 18, 2013

I seek analogies, historical morphologies. The struggle for the self-determination of a polity that doesn’t yet exist. The earth battles us with our own strength: Antaeus in reverse. We must world. [I.H. Finlay: Not all gardens are retreats; some are attacks.]

First assemble your army and the enemy will present itself in due course.

When survival of the species comes to be at stake, money will be no object: formula for communism.

We must break the bunker mentality. Monsters, not masters.

*

Arendt never wavers in her devotion to Enlightenment values—unlike the Frankfurt School, very unlike her teacher Heidegger with his ahistorical atavism. Arendt believes in freedom; it is the human task to build a world capable of sustaining the realm of political action in which and only in which freedom is possible.

*

June 20, 2013 (Ithaca)

The past is a virtuality in the present, a potentiality of the future. When Marcel tastes his madeleine or stumbles on the paving stone the past comes alive to the point of overwhelming the now. The dialectical image in action. Messianic residue of the possible.

The world of the Titans is prior to the law—outside it, before it. The Law was put into place to restrain them and to put at Bay their terrible creative power. (Thoreau: “What is this Titan that has possession of me?”) But they are still at work. In a world without gods, the Titanic becomes a live possibility, a dialectical incipience.

Whitman’s “adhesiveness” as counter to the devouring embrace of Titanic matter.

*

May 15, 2014

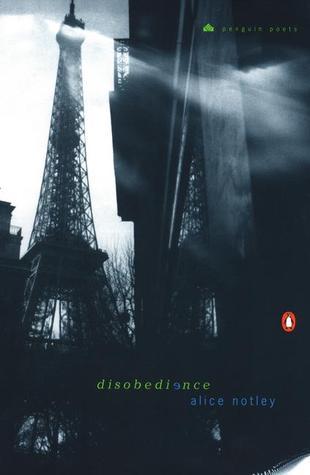

Alice Notley offers a doorway into epic via noir: "I dream I'm a detective a man / trying to catch a woman... / She is the soul." "No I want real and dreamed to be fused with the real / rip off this shroud of division of my poem from my life." Carrying dead fathers like Aeneas. Disobedience is freedom and the price paid. My Hannahiad too might dissolve boundaries between fact and fiction, biography and autobiography, reality and dream.

The Master is Will. The Master is like Notley's Hardwood, her Mitch-ham. Hannah is like Alice, caught between being and being-with-others. "'I love my Pocahontas but not my Us.'"

Or: the Master is the will to universalize the provincial, the "inner truth and greatness" of one people, or even one segment of people. And then there are spirits like Simone Weil, "citizens of transcendence" in Fellini's phrase: Saints. And Hannah, replicant and Jew, is caught in the middle, in the rapid diminishment of public space.

What is an artist? A provincial who finds himself somewhere between a physical reality and a metaphysical one. Before this metaphysical reality we are all of us provincial. Who are the true citizens of transcendence? The Saints. But it’s this in-between that I’m calling a province, this frontier-country between the tangible world and the intangible one—which is really the realm of the artist.

— Federico Fellini as quoted by John Berger in Keeping a Rendezvous

"We have come," the spirits told Yeats via the mediumship of his wife, George, "to bring you metaphors for your poetry."

Hannah is a nekyia, the other end of the telescope from elegy, the journey to the underworld. Hang it all, Robert Browning....

Reading The Cantos wrecked me, for I can never un-read them!

The most open, ragged, dialogic, philosophical, and self-aware mode of narrative is SF, engaged critically and productively with its own virtuality; in that sense it is very close to poetry. Vision. Analogy. Allegory.

The apotheosis of the Master is achieved via his slave.

*

June 27, 2014. Ithaca.

McKenzie Wark: "But really, up against the lithosphere, politics may be as uselessly superstructural as fine art, or as imaginary as the Gods of the religious." The lithosphere!

Politics as Arendt imagined them may be no more adequate to the Anthropocene than Heidegger's thought was to Nazism. Yet the pattern of implication is there.

Heidegger's "world" is indistinguishable from what Arendt designates the realm of work: that which creates the real world, the world-that-matters, the world of action.

*

Karl Jaspers said, "How is such an uncultured man like Hitler supposed to govern Germany?" And Heidegger replied "Cultivation has nothing to do with it. Just look at his marvelous hands!"

[His marvelous, tiny hands.]

And this sits oddly by another remark Heidegger made in a 1936 letter to Jaspers: "At times, one would like to have several heads and hands."

In a letter after the war, in a letter that either Jaspers never sent or that Heidegger never received, Jaspers wrote: "I greet you from a distant past, from beyond an abyss of the times, holding steadfast to something that was and that cannot be nothing."

Possibly the closest Heidegger ever came to an apology for his conduct: "Coming to terms with the German disaster and its entanglement in world history and modernity will take the rest of our lives!" Arendt's dismissal, almost a form of forgiveness, speaking in her essay "The Image of Hell" of "Heidegger, whose enthusiasm for the Third Reich was matched only by his glaring ignorance of what he was talking about."

"In Auschwitz," Arendt writes, "the factual territory opened up an abyss into which everyone is drawn who attempts after the fact to stand on that territory." Or as Vallejo seems to put it: "Don't we rise in fact downward?"

*

Arend'ts life traveled inconceivable distances: from the German student of the 1920s to the Jewish refugee of the 1930s to the political activist of the 1940s, life after life, until by 1970 she's gossiping with Mary McCarthy about the antics of Robert Lowell while turning down marriage proposals from W.H. Auden!

*

The growing sense of my project as theatrical (Mary Ruefle quotes Ralph Angel: "The poem is an interpretation of weird theatrical shit"). A masque.

Homophonic translations of poems by Heidegger, the German title for which is Wurf der Flamme, "Fling of Flame" in Jack Hirschman's translation.

Worser FlameWorser FameWorser FrameUnto FlameWorse Her F(l)ame

The earth is an archive of potentiality.

December 3, 2017

Nothing for Texts

As though assembling and disassembling my own plausibly denied youth. The stoners offered to set me up, toke me, put my head in rainbows—“we want to see what you’ll say.” No, I said, afraid of the law, of myself, my vocabulary’s enough drugs for me. My vocabulary…

Another interrogation: the heavy lids, the loose tie, the yellow nails, the smirk. His mother just offstage pulling terrible quills erect. “But why did you resign?” “On this island…” The letters have stopped speaking. Head lolling, amused and unafraid, in the cabbage patch with the other Bibles waiting to be plucked.

Thousands of us downloading songs that question their own value and putting them in our ears! on trains, on buses, on subways, in the street, in classrooms, at home. Journey to the interior. “I think the train is lost.” “How can it be lost? It’s on rails.” The Darjeeling Limited (2007): another festschrift of quirks for our consummation. Owen Wilson’s wounded head.

A secret verb predominates over the paragraphs that mostly seem to concern themselves with the presentation of certain facts about how we live. Being poses as Becoming in a dark alley. Becoming waits for Being outside the stage door, methodically beheading the flowers in Being’s bouquet.

In a minor key, as it were absentmindedly, we chain ourselves to each other and call the chain taste. This gregariousness is as political as it is disorganized and weak. Then you may read the tea leaves at the bottom of a thought-leader’s cup. We live in the age of rock and roll and the niche market. Transgression is now of the sender, the eroded establishment of a watchmaker’s values. We are best.

Stupid with fatigue derangement ranges outside any logic.

Thither and yon, holding palaver with the brute creation.

*

You needed springtime to need you,

so you shut the black umbrella

you’d been mistaking for the sea

and the real unbidden Adriatic

spilled over your hands. So too

I heard a voice calling me from Triestine rooftops—

my unborn reader, aswim in the dark

pinked perhaps by Cretan light

where my wife’s belly finds its separate sun.

*

A bedside lamp, a television, Curzon Street. Not the place of conception or authoring, only a passage to your being here.

Mika on the Underground under rain. She holds my hand, lets it go, swings through the crowd, I find her again. Thameside, Thermidor’s failed sparkle.

*

The what and the how of writing, their separable necessities.

*

lease

prudery leashes

and lashes me

scarcities

compared to an inner thigh

makes mock and motion

of mine so stupid

to fail and fall

brimcup the

ruined sidewalk

first skirts

of the season after

endless pairs of cracked and crackling

consonant ankles

compare

this vocative O

*

Stigmata are golden, my father always said

nodding off the cliff of his Barcalounger

while Laurence Welk threaded the needle of another Sunday night.

It doesn’t make a lick of sense, but after, strung up

or out in the schoolyard or man on the dump,

I think of him slack-jawed in that famous blue light.

Then a cloud passes over my forehead, a click

and the renewed whir of the sump pump

gives me a jump on mortality. If thine eye

offend thee, pluck it out, and leave

it wobbling on your TV dinner’s tin tray.

*

unsupported assertions based in personal trauma

*

Another long night of king crab legs, cell phone casings, nine-volt batteries piled high, clean dead water on the flow. Now dawn’s rosy filings cast a long shadow on my unearned prosperity: overheated peonies, greenhouse schoolchildren, the widening solar absorption zone. In the middle of it all behind drawn shades my newborn family romance: mommy baby and me, sweet Sadie’s wise and terrible blank gaze. On some savannah somewhere charismatic animals leap and die for a poacher’s camera. On the edge of the Amazon a burn soots the faces of men who will feed their families for one more day. A trawler scrapes the bottom of my melodrama, getting and spending a spent force. Polar bears cavort before drowning, we subscribe to it all: force majeure.

*

Small pink hands, purplish under the nails, a frayed nip of skin at the tip of her right forefinger. Little legs, pinker still, crossed at the ankles, wearing no-slip socks. Top of her head mingled thin dark-and-light brown hairs, cradle cap, fineness of eyebrows. Shut eyelids with the same inner hue as the nails. Nose the slightest of convexities, not yet the proud flare of her mother’s or the Roman thrust of my own. Recognize my own lips, the mouth that defiles, her mother’s stubborn chin.

How to embrace you in this arms-free hold? Cup of coffee, books, notebook, pen. A little weather system beyond the border of this sling like a canoe strapped to my chest in which you, sleeping, voyage. A new thing under the sun, but it’s cloudy today, threatening rain, and the intransigent cars hurl by. I am telling the old story

of helpless love, imagining futures fast so they can’t come true, your canoe bobs and eddies in the wild stream of a dying planet—planet means wanderer. I mean a happy ending before dying, or after; I bequeath you flesh, shit of the exhausted earth, compost of Keats, to feast on your closed and peerless eyes.

So much bigger than you. As we imagine G-d, as children to parents, the parents they’ll never meet when they’re older. There are only vagrants, strangers, coming in with thunder. I do what I can / And no more. My mother’s letter of resignation—you’ll never read it, I promise only this, never to break

what can’t be broken.

*

Brussels, surrounded by foreign academics. How even the most fluent speaker of English language, when not born to it, sounds golden and impressionable as a child.

*

The spandrel as variant sustaining the sameness of a system.

*

Word and world as fraternal twins.

*

Pounding up and down on the environmental actual, which withdraws and withdraws. I’ve got this toaster. I’ve got this magnifying lens.

*

“We change the speech because we are not explaining, agitating, convincing: we do not write what we already knew before we wrote the poem.” George Oppen.

*

Daughter as desiring machine. Her fingers marking the waterglass.

*

Oppen: “I am the oldest promising young poet in America”

*

Do you remember not owning a phone?

*

he wore nothing but a bowler

and a mason’s apron printed with arrows

down toward concrete particulars and hairy toes

up toward ultimate premises did

I mention the cigar?

*

terrible tunnel of no wind

terrible tunnel of the eye

howl of flight fringed by the iris

the unloved body shrinking at the center

shrinking and twisting like water in a drain

alive only with your own life that you now have less of

every shade drawn

void of course

holes in the walls

irretrievable tunnel cannot unsee

bed at the center the unanswered crib

face perpetually unmasking itself

face still a face though abandoned of motion

face still a face in the shattering pond

whether she led you by the hand or you led her

set down on a bench I’ll be back in just a moment

alone in the play of shade leaves the splashing of a fountain

perfectly level horizon of water just to the right

no clouds at all and cries from the playground

getting restless and shading your eyes with your hand

the companion does not appear

wait a bit longer as the sun is going down

water streaks its colors to the point your vision fails

as mothers collect their children or are themselves collected

dark as it gets by then still sitting a little longer

and pay again the price of opening open eyes

*

My daughter pulls down mud, she pulls down sky, big red barns and moons in pails and great green rooms and fields she bends to kiss or lifts to wear as a hat.

My daughter pulls down Lovecraft, she pulls down Patrick O’Brian, she pulls down Proust.

My daughter whinnies, slick foal, she pulls down William Fuller’s Sadly and Lyn Hejinian’s Happily.

My daughter pulls fiercely, she pulls attentively, she pulls carelessly, she pulls down colors, she pulls down black and white.

My daughter tucks the tip of her tongue between lower lip and gum, she pulls down Allen Grossman and Allen Ginsberg together in a ungorgeous New Directions heap.

My daughter pulls down my vanity, she pulls down her pants, my daughter claps hands.

My daughter plants petals in her hands and turns them, from a distance she sees me turn my own petals, my winged hands.

My daughter nibbles on corners, chomps on chapters, she gummed the messy baby in her copy of Messy Baby until no baby was left.

My daughter pulls down.

My daughter pulls down a name from the air, from her parents’ lips, from interested parties. She turns her head now.

My daughter in language but not yet of language—of thrips and chirps and splutters and warbles and ululations and giggles and coughs and never too far from tears.

My daughter pulls down hat, she pulls down hot, she pulls down hi.

My daughter who will know only and for years a black president. My daughter pulls down my vanity.

My daughter pulls down heavy volumes I can rescue her from but for how long.

My daughter pulls down a box of hand-me-downs and plays peekaboo with the pages.

If my daughter touches her hands to the top of her head and holds them there looking grave underneath we understand that she’s invisible.

My daughter pulls down my gaze and my thoughts from a desk far away, littered with judgments.

My daughter pulls down banners and raises them again.

My daughter pulls down the flag of her future disposition till it’s indistinguishable from the carpet.

My daughter pulls me down to her, I rise with her inexorably, soon into language but for now sweet pure speaking—

My daughter pulls down apple, she pulls down walk walk.

My daughter my daughter she pulls she pulls she pulls me backward and hurtles herself forward oh go ahead change.

My daughter turns her head and sees a sound.

My daughter laughs, sometimes she laughs at me.

My daughter pulls down Mama, she pulls down Dada.

Oh go ahead and stay the same my daughter if it costs my daughter pull me down to you among all the books and tatters where we crawl.

*

I don’t pay for it. I always pay for it later.

I never gave at the office. I always loved and hated.

I never hated. I always wore white gloves.

There is that much language and all

of that luscious. Says to me sarcastic,

Well, Josh, why don’t you let it out, then?

President Obama the end to every alienation.

Those people were a kind of solution.

September 7, 2017

Hannah

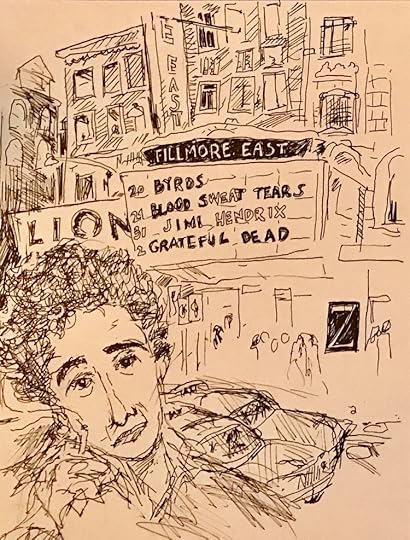

Drawing of Hannah Arendt by Ken Krimstein.

It's my very great pleasure to be able to announce that my science-fiction fantasia on the affair between Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger, Hannah and the Master, will be published by Ahsahta Press in 2019. Thanks to all the editors and friends who have supported the project!

February 9, 2017

Song

anxiety

and hope

are indistinguishable

on a physiological

level

yes

anxiety and hope

are indistinguishable on

a physiological level

that was a bus

anxiety

and hope

are indistinguishable on

a physiological level

that’s what I said

anxiety and hope are

indistinguishable on

a physiological level

that’s my song

November 17, 2016

November

What is to be done?

Take to the streets! But there are no streets worth taking in this country. Or to put it more positively, the streets already belong to us. The cities are with us. It’s the roads we need to take. The roads and the fields and the exurbs and the shopping plazas and the call centers and the malls. Especially the malls. And the churches. We need, maybe most of all, to make our presence felt in the megachurches. To be up on the big hallelujah screens with our gospel and our skin colors and our genitals and our weird ideas about ownership and our love.

But we don’t really want to go there, do we?

We want to be angry atheists and the sexiest man or woman alive in our local socialist cell. We want to carry signs and shout ourselves hoarse until every last slogan sheds its irony. We want to block highways obstructing the traffic home of those who mostly already agree with us.

I just wasn’t made for these times.

I wanted to say something about Neruda in this poem, something about his questions, something about the autumns of Neruda and how we don’t count his 9/11 as he couldn't count his Novembers. But Neruda it turns out was a rapist and so I let his ruined magnificent head sink out of sight, like Cortazar’s ship of fools, like a blind trail into the mountains. No pasarán that way. No way out.

The I appears, a Jewish I at the precise historical moment when such an I, like the I-beam it resembles, is no longer load-bearing. As in brutalist or postmodernist architecture the Jewish I has become ornamental, where it is not being used to build the containment wall in the West Bank. The Jewish I used to be adequate symbol for the man on whom the sun of history had gone down. That’s Ezra Pound I think. His anti-Semitism no longer scans. I are on its own.

I have a Jewish I that resents the limited means of political expression on sale at my local Target. Marching, shouting, boycotting, signing petitions, calling elected representatives, writing letters, writing emails, writing tweets, writing status updates, writing poems. My I doesn’t like any of those choices except for the last one, which you can’t buy from Political Target because it’s free. I already has a lifetime supply of its own uselessness.

And my Jewish I lives in a safe state called whiteness where my vote doesn’t count.

And my Jewish I is a male I that never measures in millimeters the space between his knees when siting on the train writing as I do right now, the sun picking its path through the skimpy trees of November. November! Remember before November our idea of November, in the era of the endless election how we looked forward to everything being over? How wrong we were, and how right.

But this is precisely what’s defective about the I that I can’t return to Political Target for a refund let alone store credit. This Freudian shilly-shallying. This conviction that every conviction I muster and direct from my mouth is met and confounded by its opposite churning in my breast. Maybe it’s because I’m a Libra. A Libra sees both sides of every question. Its symbol is a set of scales that ought to symbolize judgment, but really symbolizes its opposite.

And is the suspension of judgment the same as the suspension of justice? It must be. And if I live in such suspense, must I expect those with a thumb on my scale to prevail, always? Very true, Socrates. They came for you, didn’t they, an hour before dawn. They permitted you your magnificent defense—you, the enemy of the poets. Then you drank poison, which quickly destroyed the serenity of your flesh. A debt left unpaid to the healer. You wrote nothing. You had nothing more to say.

I’m reading theory again, Alain Badiou mostly. He has a good global diagnosis of our situation, go read it. I’ll wait for you to come back. http://mariborchan.si/video/alain-badiou/reflections-on-the-recent-election/

So you’re back and I see your skepticism, it’s written all over your face. He wants to imagine a different world, you sneer. He wants to offer this world a genuine contradiction. He believes that poor old Bernie Sanders represents a true contradiction of the system that both Hillary and Trump are inside of and are almost equally incapable of opposing. He wants to feel optimism. To be left alone to write his poems inside the old sharpening of the contradictions routine. He’s forgotten Rosa Luxemburg. He’s forgotten the fate of the Popular Front. He’s forgotten how to bleed, if he ever knew. He’s a coward cowering with his books.

Comrades, I say. I wait for the bitter laughter to die. Comrades.

You are waiting for me to say more. The silence is growing uncomfortable, as we are all uncomfortable in this hot and dusty room. A room with no windows and only the door by which we entered. A room you might hold a twelve-step meeting in, or a police interrogation. A room with no character, no life, but that which is placed in it. A room of reverberate walls. A room of the mind and its patience. A place for the genuine.

Comrades.

And again, Comrades.

The murmur is growing as it becomes clearer and clearer that I have nothing else to say. Nothing but your word. Comrades.

Comrades, my tears. A word. Comrades.

It is something with which to begin.

November 13, 2016

The Barons 2016

A poem rededicated -- to the President-Elect

In the time of ever more rapid diffusion and dispersal of truly humanistic termini

The time of collective seizure of rapidly diminishing carbon cores

The time of the barons in their towers growing fatter unto death hooked up to

dizzying interconnected internet spirals of IVs sucking everybody’s placenta dry

Aka your milkshake aka my humps

In the time of dominoes laid from one end of the asylum to the other

The time of male whores who can’t catch a break

Time of the underground economies trading hot licks for rapid desertification

Time of distant thunder

Time of the perpetual el niño

Time of rain filling the abandoned moviehouse and everything picturesque and

prepared for the ancestors

Ancestor-life the only scale that matters now the scale of the illegible the illiterate the unread

Not just a hitler but many come-hitlers in the twilight bathrooms of the barons,

making their dicks look small

Being now of sound mind and sound body I, thirty-nine years of age brimming with half-spent undessicated nougat-rich mortality

Say unto thee children, Burn the motherfucker down

*

Now you’ve written something and given birth to a critique

First critique says it’s in your mind time and space

Second critique says you know very well what to do

Third critique says there’s no arguing the taste of this poem yet you’ll go on wanting to

Mid 5-am mid-future sleeping families strap on the masks

Air conditioners gust on outside dark houses disturbing the rats

Electromagnetic impulses making the circuit of the only world

I thought gnawing my own leg off would be one way out of the trap

Then I thought dying in the attempt would be another, truer way.

*

burn baby burn that’s the only spirit that matters

Literally burn the baby endless fields of fucked burning babies

The barons walk the line innocuous and off the rack

They’re with you tonight in this room they’re with you tonight in your televised bed

They’re with you tonight in Rockland they’re with you on your tax forms

Just because it’s freaking obvious doesn’t make it untrue

Why this is hell nor am I out of it—master the line of Mephistopheles

*

My mind won’t let me rest until I record here what I’ve seen

Four lines of fire razing the land at slightly different rates

Parallel lines with just enough space between to make a vista

There’s no point in making your planet a hell unless you’ll have a view

The first line is rapid and distills a smokeless flame visible from airplanesMapping the earth’s abstract grid a seamless seam running the cornfields

Second line moves more slowly and mostly invisibly wastes the sky

The third line makes lots of stops punctiliously burning each city from the outside in

From suburbs of immigrants and favelas like nooses tightening around the necks of people that look like me

That one sets fires at random it takes a long view to see the line

The fourth line is last and moves more slowly than the senses can detect yet rapidly

becoming irreversible

It’s this one that scares me motherfuckers it’s the hellhound on my trail

Close my eyes and I see it spiraling from the horizon flames a mile high crisping

everything

Rendering the ground a fertile-seeming black casting down towers and malls into architecture

Blown back by the slow-mo blast that is eating bit by bit my halo and wings

Eyes shielded from burning pitch and grit solely by remaining open

Backdrafted into a future built on the continuous present of ruination

YOUR NAME HERE thou shouldst be alive at this hour

*

Burn, baby, burn. Commas serve the deficit of reason.

I’m an attention-deficit hawk I say we have our eyes and lips sewn shut

I’m a suburban father with invisible tattoos on my body

Which small or midsize SUVs have a column-mounted shifter?

Be inspired. Great selection. Our instinct is to catch the baby.

Drop the old ones into their holes. This life is a Viking funeral.

Like speeches made by law into public address systems that render the words

unintelligible.

True of every platform. The railroad rides upon us.

The appearance of full-stops serves the appearance of rhetoric.

An argument in 1934. Young men are so young.

The appearance of caesuras serve the appearance of violent birth

Subdued to softer adverbs. Mechanically. Psychometrically.

Pastoral a function of our language. Groves are generative grammar.

The trees of truth cut down. “Tree in the ear,” Wunderbaum.

Inverted tree of an underwater oil surge.

Its roots come grasping for us.

And all tomorrows surfacing.

*

Let prose handle the inwardness that personal history sells

Let the poem spiral outward like the Kraken in secret thunderdome with Leviathan

Pulling the unread and unseen into mutual unequal struggle

Game of the corporate state hides the identity of the barons

Preaching to monster trucks to pine cones to stacks of burning children’s books

Listening respectfully to their own beards the powerful uneducated persons

The fire lines are racing which will be first to reach the goal

The end of every burning

*

“a man who wails is not a dancing bear”

And a dancing bear isn’t a bear and it isn’t dancing

It’s an it for our fascinated contemplation layers of years like Band-Aids

Now and of an age that surpasses ours in cruelty

Since cruelty requires attention that endangered natural resource

The bear in its Elizabethan ruff its fur and privates torn by pit bulls

Baited on its hind legs beats its chest with claws for the spectators

Who stand in a ring, backs turned

I like to go to the game and listen to it on the radio

I like to be larger than life and vanish on your retina screen

*

Seeing is material and being seen is spiritual

The more you walk the streets invisibly the closer you are to death

Rich reality of death foaming in bones and capillaries

Death shining at a millimeter’s distance from every moment of skin

I think I’ll buy a malted for the writers in Ghana these days

No one is deader than the reader more material sunk in aliveness

The barons are angels shining their bodies themselves are halos

Eyes uplifted to live feeds tracking the movements of material witnesses

Listening to “John Wayne Gacy Jr.” I am really just like him

If homicidal homosexual clown isn’t an orientation oh my god

I am not a baron maybe a little bit baronet

It’s my pleasure to serve the oligarchy by not mentioning it too often

Every time I click this link it’s like I’ve gone to church

The contents of their stomachs are mostly plastic

Decay generates the only heat that warms an angel’s bones

*

Let silence bring to presence. Silence. Silence.

There is still a little shade

Trees are noisy

Silence

Waiting to be killed

Bodies quantifiable

Whatever silence

Have it your way silence

I don’t care silence

Depart from this place

See what you have created

&

see the barons

the barons unmade

August 12, 2016

From a Notebook in Vermont

View of Lowe Lecture Hall, Vermont Studio Center

Brainless with anticipation on the flight here, unable to settle on any of the books I brought: Homero Aridjis, Joseph Donahue, Ann Lauterbach, V.S. Naipaul. But the title of the last book follows me: The Enigma of Arrival.

Looking forward to the sparkling drudgery required by art. Goodbye Lake Michigan, goodbye. Midsummer, midlife. "The mid-world is best," writes Emerson. "Nature, as we know her, is no saint."

On planes I think of death though I have no particular fear of flying. The sky is undistracted reflected in Lake Champlain below.

Now I re-enter that skin I only wear when alone. Solitude, for me, is the opposite of an experience of depth. In daily life there's so much that goes unexpressed, because there's a time and place for everything. Solitude denies them both; I skate on the surface of whim.

Aridjis, The Child Poet: "As if inside a luminous sphere, I traveled within the day that brightened my room and, all eyes, would observe from bed the things that surrounded me, feeling an arousal of those things in myself."

In even the smallest airports the buzzing, blooming confusion: momentarily stranded, making connections. Bodies in space avoiding the wrong kind of collision. The wish, quite literal, to rise above these particulars.

Where did it begin: this habit of elevation, of instinctive or reflexive transcendence or avoidance of the particulars of experience? The experience of loss for Emerson was "caducous," meaning an organ shed at an early stage of development. "I grieve that grief can teach me nothing, nor carry me one step into real nature." As if grief were a moving sidewalk. In Vermont I am an aerial being among the mountains and rivers.

View of the Gihon River.

At dinner the residency director invites us to take time to refind the "why" of our work. But I have come here typically task-oriented, to finish the novel I've been writing since this time last year. Blue notebook squats like a toad, reminding me my first task is to finish transcribing it. In a little city of visual artists I cling to my own handwriting, the one real object I have.

I get distracted with no distractions. The scenes that I wrote on the train still have in my mind the train's rhythm. When I finish one I want to get up and walk around instead of moving on to the next. But it's raining; I return to my desk. A family of skunks plunges out and in of the long weeds ranging the riverside.

Almost missed lunch dreaming in my studio. I've never had such a thing: a dedicated space for writing. It feels a scandalous luxury. I cover a cork board with pieces of manuscript and tokens from home. The desk is already a sprawl of books, coffee mugs, papers.

The I is the lyric's baseline, the guarantee of a subjective structuring of whatever falls into or out of the poem. A first-person narrative can behave similarly. Plots and subplots serve the role of the objectivity that pressures the i to disclose what it is. That makes fiction indirect in its lyricism.

The poem makes a trance in the writer; narrative prose makes a trance in the reader.

Most of the artists here are young and childless. For the duration, I suppose that I am childless too. I pay for the privilege by becoming ever more insubstantial to myself.

Sitting and reading by the river on a cloud-stacked beautiful day. A poem comes, the first in a while, and I give it a title from Olson: "My Name Is No Race." When I read the poem in public it reminds someone of Charif Shanahan's "Wanting to Be White."

When I was much younger poetry was mostly about the freedom of association of words. I took for granted Richard Hugo's assumption that truth be made to conform to music. The reverse was reserved, Hugo said, for virtuosos like W.H. Auden. But this summer I've been rereading Auden and the experience reminds me of my experience. That is, at 45 there is more behind and beneath my words than in the days of sheer intoxication. There's a moral career for my words that demands a new courage to be simple. And the rediscovery of rhyme, which as Reginald Gibbons suggests can be poetry's via negativa, a doorway to its apophatic register. A talk by Joseph Donahue quotes Robert Duncan on the Master of Rhyme:

The Master of Rhyme, time after time, came down the arranged ladders of vision or ascended the smoke and flame towers of the opposite of vision, into or out of the language of daily life, husband to one word, wife to another, breath that leaps forward upon the edge of dying.

Donahue's talk is on "the poetics of the vertical," but another way to think of this passage is via Gibbons' notion of the apophatic versus cataphatic in poetry. Cataphasis means "to make visible"; poetry in English, claims Gibbons, tends to be cataphatic, because English's saturated lexicon makes it an Adamic language of naming. Apophasis conjures the invisible, the unseen and undone; one of Gibbons' examples comes from the Gettysburg Address: "we can not dedicate--we can not consecrate--we can not hallow--this ground." (Which hearing again makes me hear an echo of Shelley's lament in his "Defense of Poetry": "We want the creative faculty to imagine that which we know; we want the generous impulse to act that which we imagine; we want the poetry of life; our calculations have outrun conception; we have eaten more than we can digest.") French and Russian are friendlier to apophasis. Francis Ponge, as Gibbons notes, is a curious exception to the rule of a tradition obsessed by l'azur or what Yves Bonnefoy calls "a crystal sphere."

Of course what Duncan and Donahue mean by "vision" is probably precisely the apophatic; the visible world is a fallen one of apocalyptic "smoke and flame towers." But Duncan's image comes from Exodus; the pillars of smoke and flame guide the Israelites out of Egypt, like vertical hyphens between the social and divine. I prefer to travel the paths of the implicit chiasmus between vision and the opposite of vision; between a saturated poetics of naming and the pressures (pleasures?) of the void.

Fiction seems very clumsy to write after reading the poems of Joseph Donahue, particularly the long title poem of his recent book Red Flash on a Black Field. Seemingly without effort from line to line and section to section he evokes worlds and narratives, colliding with easy precision encounters of the sacred and profane. Landscapes rhyme with one another, toggling implicitly between vision and its opposite:

A desert above a river,

a heaven beneath a mountain.

...................

A lake beneath the desert,

grain in a field above a cloud.

A flaw drains light from a dog run.

The mud is a treble of mutts.

One ear hears the gentle stillness of the night,

the other hears troops take a beach.

Together, ears hear the sound of men

singing "Dear Father," though

clearly not in English.

Childlike, the Vermont landscape. I've landed in the Shire.

The shepherdess weds her sheep in a miniature pastoral drama, courtesy of Bread and Puppet Theater.

Nicanor Parra makes a surprise appearance.

The man with the sky in his eyes.

As above, so below: the Pageant.

River, birdsong, stuttering hedge-trimmer.

"True Love Waits" moves me to tears. To keep faith with those who abandon you. Radiohead is a complete theology.

Small panic every morning at the finitude of this. River of sky above me, heaven of waters below.

Dreams of the blue notebook, taunting me with its endless pages. I want the feeling of finishing, though it's only the breaking of surface tension. Apres ça, la déluge.

The best part of any story is the down-time, when the machine of plot ticks to itself in the background and the characters get to know each other. Richard Linklater's entire career based on capturing that experience.

A poetics of digression weaves easily between the named and the ineffable.

Trying to finish a novel feels just like those dreams where you're trying to run but your legs are too heavy to move. In dreams I'm being chased; in writing I'm doing the chasing. The experiences are almost the same.

An idyll has to end; ending is in its nature.

Peter Turchi: "Diner is essentially a remake of The Canterbury Tales."

The concept of "curated digression."

Finished transcribing the blue notebook, robbing it of talismanic power. The printout of the draft sits massively on my desk; it has a dimly charismatic glow. I try to take pride in its objecthood. But a novel has a weak existence except when someone's actually reading it.

Cool humid breeze. Lush green. Trees and cascades of wind. Herding cumulus clouds. The earth apparently unruined.

Sense of place often richer than character.

The livelong day.

I write a second poem. Novels are so Protestant and middle class, presenting a horizontal quantitative earthliness. It takes poetry or science fiction to pursue the hubris of cosmology, the vertical.

But is the vertical or apophatic more than a gag reflex, a mighty sublation of disgust? With bodies, the sordid push, mortality?

[image error]

"Too fucking pretty": an artist's notes to herself.

Solitude edges into loneliness and back again. Sunday noon on the lawn overlooking the riverbend, keeping company with the clock tower and clouds, in a circle of wooden chairs shaped for last night's revelry. Solitude is concentration of force and loneliness is its opposite.

For the other residents here I'll always be the guy who talked-sang "Piano Man" on karaoke night, half Billy Joel, half William Shatner. It's taken all my life to become a little at ease with my own uncoolness.

"My Name Is No Race." Race sticks in the craw of the vertical, or else gets appropriated into its service; what is white supremacy but an organized effort to transcend the impure conditions of mortality? The black gospel choirs that turn up in white pop songs. We danced to "Like a Prayer" last night.

A problem you can dance to.

Some fundamental tension goes missing when I try to write the personal.

Eros floats free in places like this and it isn't necessary to do anything about it. We pass lightly among each other. We touch hands, voices, glances.

A third poem; hard not to feel that each has been a falling off from the first and best. So much paper left behind recording a fraction of all I've expressed. Condensare, signore.

A place like this cuts off adulthood at the knees. When the visiting artists bring children, it's a gentle shock of mild surprise. My daughter like so much of my life is going on without me.

Why are cumulus clouds charismatic? They are so palpably in three dimensions. Flatter or more dispersed clouds don't challenge our impression of the sky as an entirely virtual space.

Poetry like breathing when I'm so little interrupted. I interrupt myself: why?

Frantic white butterfly hurries on and off the stage. Its mind must move faster than mine if it ever experiences any peace.

Clouds in the north grow black bellies.

Global warming makes more palpable the distinction between the real laws of nature and what it turns out was only habit. To put things another way: fate is not to be fucked with.

Saints I seem to need: Proust and Woolf and Joyce. Saints not by personal virtue but by example of their devotion.

I can't seem to think of any poet-saints; they are too close to the medium of devotion, language.

What is it I mean? That the saints, like angels, are in exile, from Ireland or London or good health. Across the river I see three sculptors in a circle consulting their cell phones.

Poets are outrageously at home. It's offensive to the rest of us camped down under the bridges of language.

Sunshine. I have to close my eyes for an understanding of its radiance.

And though it makes me feel shy to say so, I make overtures to something like truth.

I mean things in a new way. A statue commits to its pose and to enduring all the elements of time. I'm in friction; one part good as another. Emerson: "I have not found that much was gained by manipular attempts to realize the world of thought."

Lumping through the manuscript line by line. The book that I imagined is superior in every way to the book that I've actually written. But only the latter does me the courtesy of really existing.

Chomsky claims somewhere that what distinguishes human language from animal communication is that language enables thought; we can't think without words. We communicate first with ourselves. Seems a poetic principle. Whether we speak of the visible or the invisible, we first speak the phatic, the languageness of language, the open channel itself: "Is this thing on?" A precondition for thinking is literally talking to yourself.

Shade of gray-green leaf that stuns silver in sunlight only by contrast to the more ordinary green of its reverse. Quaking steel green, aspen silver green. Fascination of a bright foreground and a black background or the reverse. When you take a cell phone photo your finger chooses between definition of the objects or the lush transcendence of the sky. What Vera Pavlova in a talk calls the "incoherency of space."

The prospect of leaving, the idea of staying: flip sides of the coin of melancholy. Give it a toss, I'm finished here.

The last line in my notebook is this sentence: "I could take a nap."

The Red Mill at VSC.

August 6, 2016

The New Novel

Completed this week at the Vermont Studio Center, my new novel, an elegiac thriller about a floating island designed to survive the end of the world and the attendant misgivings and regrets of its architect. Writing it was a dream and I hope reading it will be like one too.